Tuberculosis still remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality today. Globally the incidence of this disease is increasing by eight million new cases annually and is a cause of death for two to three million patients every year.1 The ocular manifestations of tuberculosis are diverse, and depend on the immunological, bacteriological, and epidemiological variables.2 Individuals with compromised immune status usually present with atypical presentations.3 This clinicopathological report of a patient treated with immunosuppressive agents shows intraocular tuberculosis presenting with pigmented hypopyon.

A 38 year old female patient with a history of polyarthralgia, anaemia, hypertension, and an impaired renal function with a possible clinical diagnosis of systemic lupus nephropathy underwent renal biopsy, which disclosed membranous glomerulonephropathy with peripheral granular deposits of IgG, Clq, and IgM on immunofluorescence. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated (74 mm in the first hour) and she had positive antinuclear antibody; negative rheumatoid factor, VDRL, HIV, and tuberculin skin test (PPD). She was treated with intravenous cyclophosphamide 1 g per day once every month for 3 months and corticosteroids 30 mg/day. At the time of the third intravenous injection of cyclophosphamide, she noticed deterioration of vision in the right eye. On examination, right eye visual acuity was hand movements close to face. The conjunctiva was congested and the cornea was oedematous. The anterior chamber was shallow, and a 3 mm pigmented hypopyon was noted (fig 1). The left eye was unremarkable and the vision was 6/6. Blood and urine cultures showed no growth, and smears of anterior chamber fluid were negative for bacteria and fungi. Oral ciprofloxcin (500 mg twice per day) was started in addition to topical corticosteroids and mydriatrics. A week later, the pigmented hypopyon had increased to 5 mm; it was aspirated and submitted for cultures and staining. Ziehl-Nielsen’s stain revealed several acid fast bacilli (AFB). The cultures were positive for AFB and the Tuberculosis Research Centre in Chennai, India, identified the organisms as Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on pigment production, positive niacin, and catalase test. The patient was re-examined for evidence of systemic tuberculosis. Her PPD was negative and there were no radiological or clinical evidence of extraocular tuberculosis. Despite treatment with four antituberculous drugs (rifamycin 450 mg, isoniazid 300 mg, ethambutol 800 mg, and pyrazinamide 1500 mg), and oral steroids (20 mg) for her polyarthralgia, the patient developed multiple scleral abscesses and lost the remaining vision. She underwent enucleation of the right eye and was continued on antituberculous agents for 6 months. She was continued on tapering dose of systemic corticosteroids for 3 months following a fourth intravenous cyclophosphamide injection. She was followed for two more years and there were no signs of disseminated tuberculosis during that time.

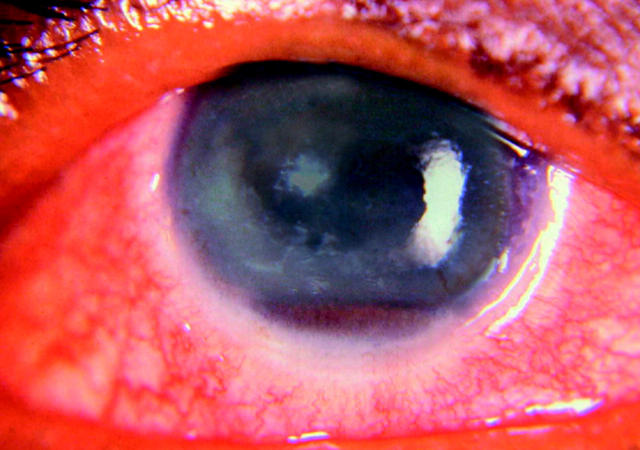

Figure 1.

The right eye shows oedematous cornea with presence of pigmented hypopyon.

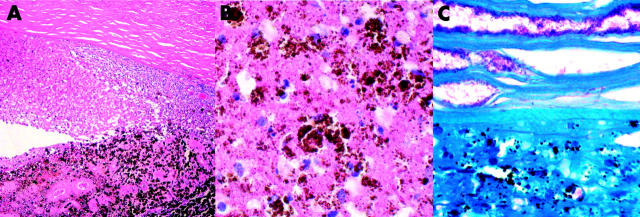

Histopathological examination of the enucleated eye showed infiltration of acute inflammatory cells and macrophages in the posterior half of the corneal stroma (fig 2). The anterior chamber was filled with pigment containing necrotic cells, macrophages, and proteinaceous exudate. The iris and ciliary body were necrotic and were infiltrated by pigment laden histiocytes. The sclera revealed necrosis with infiltration of acute inflammatory cells. The vitreous cavity contained proteinaceous exudate without significant inflammatory cell infiltration. Acid fast stains disclosed an abundance of AFB deep in the corneal stroma, in the anterior chamber exudates, and in the necrotic iris (fig 2). Histopathological diagnosis was tuberculous necrotising keratouveitis.

Figure 2.

(A) Haematoxylin and eosin stain reveals necrosis of iris and inflammatory exudates in the anterior chamber. (B) The anterior chamber exudate displays several melanophages and necrotic cells (haematoxylin and eosin). (C) Ziehl-Nielsen’s stain shows a myriad of acid fast bacilli in the deep corneal stroma and in the anterior chamber exudates.

Comment

In this case, the pigmented hypopyon was made up of melanophages. Darkly pigmented hypopyon may appear in eyes harbouring necrotic uveal melanomas in endogenous endophthalmitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes and Serratia marcescens.4,5 The cause of dark hypopyon in the endophthalmitis cases was assumed to be a dispersion of melanin from the necrotic iris.5 The present case also showed necrotic iris and dispensed melanin granules in the anterior chamber, suggesting a common underlying pathology for the formation of pigmented hypopyon. To the best of our knowledge this is the first known case of pigmented hypopyon in a biopsy and culture proved intraocular tuberculosis, and highlights the need for anterior chamber fluid analysis in arriving at the diagnosis.

The clinical spectrum of ocular tuberculous infection includes chronic uveitis, interstitial keratitis, scleritis, sclerouveitis, optic neuritis, choroiditis, retinitis, chorioretinitis, and panophthalmitis.2,3,6 Hypopyon is rarely noted in tuberculosis. Ni et al presented cases of intraocular tuberculous with turbid, haemorrhagic, greyish yellow exudate in the anterior chamber in one case, and fibrinous hypopyon in three other cases.7 Hypopyon may appear in rifabutin treated patients who had Mycobacterium avium complex infection.8 In all instances, the hypopyon was not darkly pigmented. The clinical and histopathological features suggest that the ocular infection could be endogenous; however, systemic evaluation did not disclose extraocular focus. The presence of large numbers of acid fast organisms in the histological sections suggests that the organisms could be atypical mycobacteria. However, the cultures showed that the organisms were Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Presence of such large numbers of the organisms in the ocular tissue could be from treatment induced immunosuppression.9

Acknowledgments

We thank the Tubercular Research Center (TRC) Chennai, Tamilnadu for conducting biochemical tests for Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Supported in part by Research to Prevent Blindness Inc, New York, NY, USA and core grant EYO3040 from the National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD and Aravind Medical Research Foundation, Tamil Nadu, India

References

- 1.Raviglione MC, Snider DE Jr, Kochi A. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis. Morbidity and mortality of a worldwide epidemic. JAMA 1995;273:220–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunn JP, Helm CJ, Davidson PT. Tuberculosis. In: Pepose JS, Holland GN, Willhelmus KR, eds. Ocular infection and immunity. St. Louis: Mosby, 1996:1421–9.

- 3.Helm CJ, Holland GN. Ocular tuberculosis (major review). Surv Ophthalmol 1993;38:229–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reese AB, Archila EA, Jones IS, et al. Necrosis of malignant melanoma of the choroid. Am J Ophthalmol 1970;69:91–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eliott D, O’Brien TP, Green WR, et al. Elevated intraocular pressure, pigment dispersion and dark hypopyon in endogenous endopthalmitis from Listeria monocytogenes. Surv Ophthalmol 1992;37:117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biswas J, Madavan HN, Gopal L, et al. Intraocular tuberculosis. Clinicopathologic study of five cases. Retina 1995;15:461–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ni C, Palpale JJ, Robinson JL, et al. Ocular tumors and other ocular pathology: a Chinese-American collaborative Study. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1982;22:103–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fineman MS, Vander J, Regillo CD, et al. Hypopyon uveitis in immunocompetent patients treated for Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary infection with rifabutin. Retina 2001;21:531–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zamir E, Hudson H, Ober R, et al. Massive mycobacterial choroiditis during HAART: another immune-recovery uveitis. Ophthalmology 2002;109:2144–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]