Abstract

Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of blindness in the world. In spite of the diverse therapeutic possibilities, new and better treatments for glaucoma are highly desirable. Cannabinoids effectively lower the intraocular pressure (IOP) and have neuroprotective actions. Thus, they could potentially be useful in the treatment of glaucoma. The purpose of this article is to provide the reader with an overview of the latest achievements in research into the potential use of cannabinoids for glaucoma.

Cannabis/marijuana is the most frequent illicit drug used today for recreational purposes. Yet it is not widely known that the cannabis plant (Cannabis sativa; Latin for “planted hemp”) (fig 1) is one of the oldest drugs used for medical purposes. Its therapeutic use was first recorded in a classical medicine book by the Chinese emperor Shen Nung in 2737 bc. The medical use of cannabis was also known in other ancient cultures throughout India, Assyria, Greece, Africa, South America, Egypt, and the Roman Empire.1

Figure 1.

Photograph of the Cannabis sativa plant (provided by GW Pharmaceuticals, Wiltshire, UK)

Cannabis was introduced on a larger scale into Western medicine during the 19th century, primarily by British doctors. They accumulated experience in the use of “Indian hemp” while working in the colonies, recommending it as an appetite stimulant, analgesic, muscle relaxant, anticonvulsant, and hypnotic. In 1839, Dr William Brooke O’Shaughnessy, an Irish physician at the Medical College of Calcutta, published a detailed report “On the preparations of the Indian Hemp or Gunjah.” After performing animal studies, he determined that cannabis preparations were safe and effective in treating rabies, rheumatism, epilepsy, and tetanus. The Ohio Medical Society of Physicians reported in 1860 successful treatment of “stomach pain and gastric distress,” psychosis, chronic cough, gonorrhoea, and neuralgia with cannabis. The plant was difficult to store, its extracts were variable in potency, and the effects of oral ingestion were not constant. Other new drugs were becoming available in the early 1900s with more reliable effects, and cannabis began to be misused for recreational purposes. The American Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 intended to prevent non-medical use, but made cannabis difficult to obtain for medical purposes too, and it was subsequently removed from the US pharmacopoeia in 1942.

In the United States cannabis is now classified as a schedule I drug, regarded as having high potential for abuse, and to be unsafe to take without medical supervision. Recently, several states have legalised the medical use of cannabinoids. In the United Kingdom, cannabis is registered as a schedule I—class C drug.1–4 The medical use of cannabinoids is currently restricted to dronabinol (Marinol, synthetic Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol) and nabilone; these drugs are administered orally as anti-emetics and appetite stimulants for patients with AIDS or on chemotherapy. Other potential clinical applications for cannabinoids, including glaucoma therapy, are currently under intense investigation (see below).

PHARMACOLOGY

The cannabis plant has more than 480 chemical constituents.5 Of these, there is a group of at least 66 compounds that contain only carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen and are known collectively as cannabinoids. The remaining constituents of cannabis include nitrogenous compounds such as amino acids, proteins and glycoproteins, sugars, hydrocarbons, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, simple acids, fatty acids, esters and lactones, steroids, terpenes, non-cannabinoid phenols, flavonoids, pigments (carotene and zanthophylls), and vitamin K. Terpenes are thought to be responsible for the characteristic odour of cannabis plants (fig 1). The main psychoactive constituent of cannabis is the cannabinoid, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), the structure of which was determined by Gaoni and Mechoulam in the 1960s (fig 2).5 Most research into the pharmacological properties of plant cannabinoids has focused on this cannabinoid and, indeed, with the exception of cannabinol and cannabidiol (figs 2 and 3), other plant cannabinoids have been subjected to little or no pharmacological research.6,7

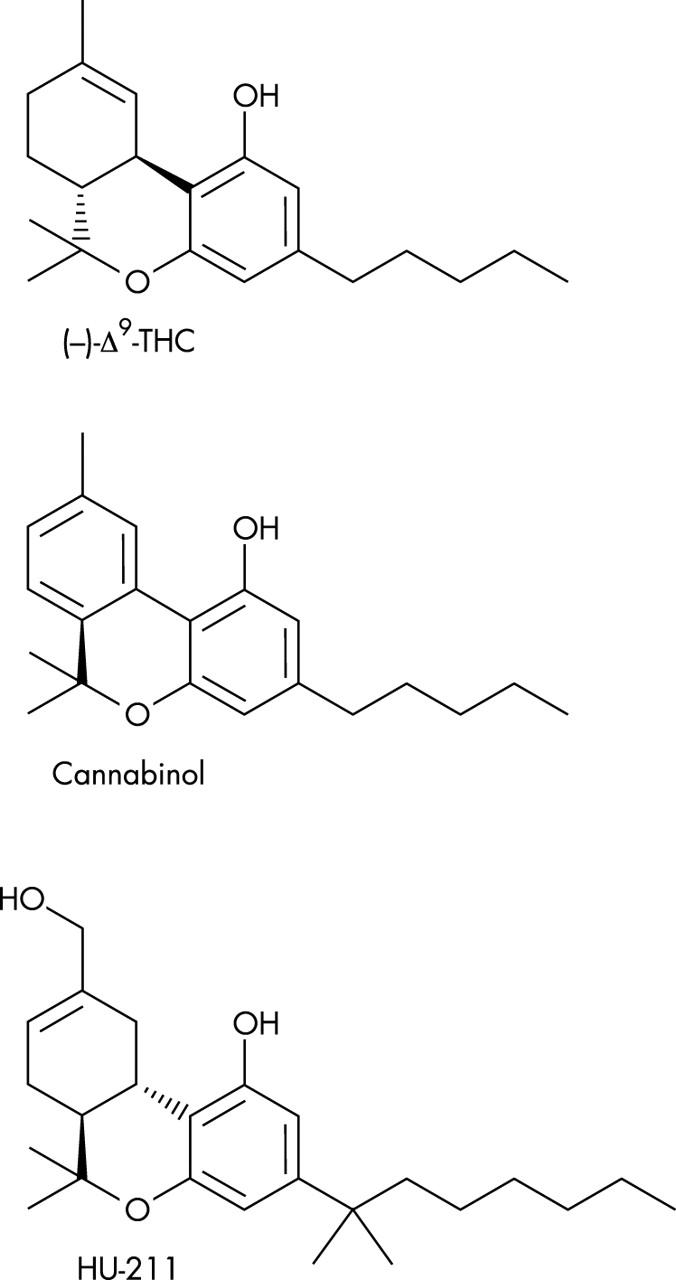

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of typical classic cannabinoids Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabinol, and HU-211.

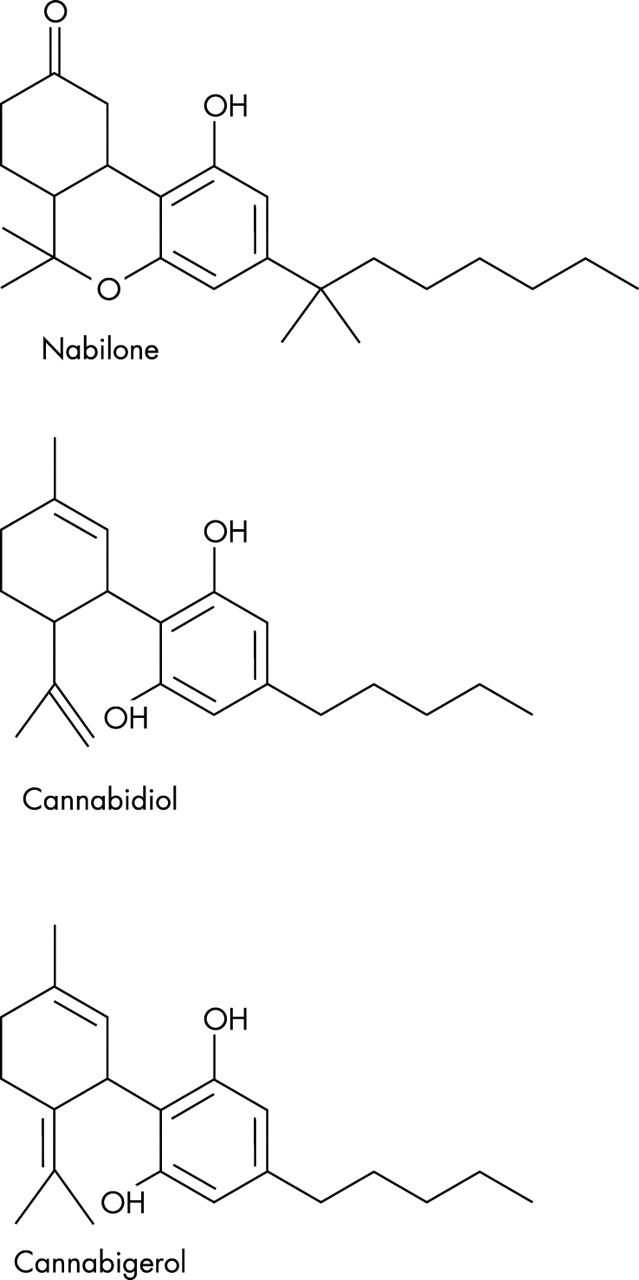

Figure 3.

Chemical structure of nabilone, cannabidiol, and cannabigerol.

It is now generally accepted that Δ9-THC produces many of its effects by acting through cannabinoid receptors of which there are at least two subtypes, CB1 and CB2.8 Both subtypes are coupled through Gi/o proteins, negatively to adenylate cyclase and positively to mitogen activated protein kinase. In addition, CB1 receptors are positively or negatively coupled through Gi/o proteins to certain calcium and potassium channels. CB1 receptors, which were cloned in 1990, are present in brain, spinal cord, and certain peripheral tissues that include lung, heart, urogenital and gastrointestinal tracts, and the eye.9–11 Many CB1 receptors are present on central and peripheral neurons, one of their functions being the modulation of neurotransmitter release. CB2 receptors, cloned in 1993, seem to be located especially in cells and tissues associated with the immune system, such as the tonsils, spleen, and different types of leucocytes.8,9 One role of these receptors is modulation of cytokine release.

Endogenous agonists for cannabinoid receptors have also been discovered; this system of “endocannabinoids” and receptors constituting what is now generally known as the endocannabinoid system.12 The endocannabinoids that have been indentified to date are all analogues of arachidonic acid. They include arachidonoyl ethanolamide (anandamide; AEA), 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG) which bind more or less equally well to CB1 and CB2 receptors, and 2-arachidonyl glyceryl ether (noladin) which is CB1 selective (fig 4). AEA behaves as a partial cannabinoid receptor agonist with less CB2 than CB1 efficacy. Within the nervous system, endocannabinoids are synthesised and released by neurons on demand, functioning as neurotransmitters or neuromodulators. There is also evidence that endocannabinoids serve as retrograde synaptic messengers.12 Following their release, the effects of at least some endocannabinoids are thought to be rapidly terminated by cellular uptake and intracellular enzymatic hydrolysis.13

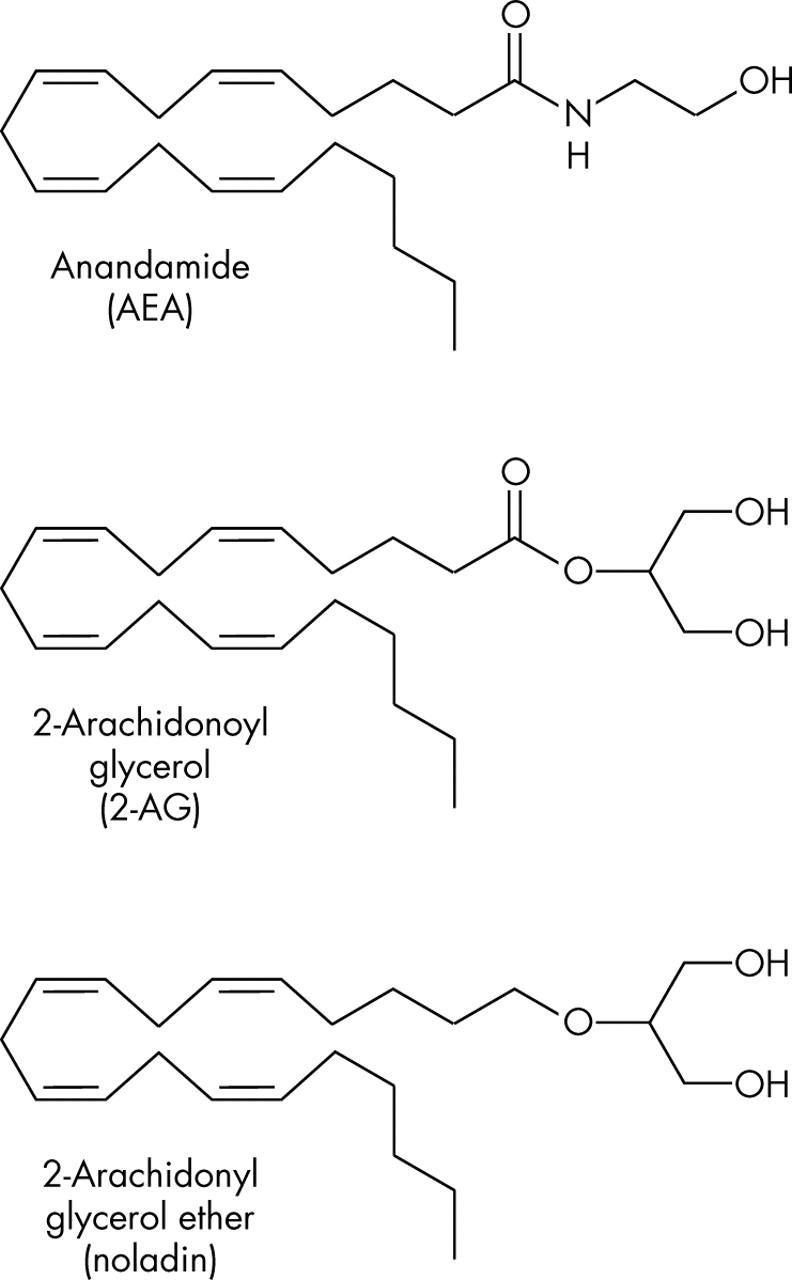

Figure 4.

Chemical structure of endogenous cannabinoids anandamide (AEA), 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG), and 2-arachidonyl glyceryl ether (noladin).

As detailed elsewhere6,8 some established cannabinoid receptor agonists bind more or less equally well to CB1 and CB2 receptors, important examples being WIN55212-2, which has marginally greater CB2 than CB1 affinity, and Δ9-THC, HU-210, CP55940, and nabilone (fig 3). As to CB1 selective agonists other than noladin, these include the anandamide analogues, methanandamide, O-1812, arachidonyl-2′-chloroethylamide (ACEA), and arachidonylcyclopropylamide (ACPA). Examples of CB2 selective agonists are the THC analogues, L-759633, L-759656, JWH-133 and HU-308. Selective CB1 and CB2 receptor antagonists have also been developed, the most important of these being the CB1 selective SR141716A, AM251, AM281 and LY320135, and the CB2 selective SR144528 and AM630.8 There is evidence, however, that these compounds are not “silent” antagonists.14 Thus, as well as attenuating the effects of CB1 or CB2 receptor agonists, they can by themselves elicit responses in some cannabinoid receptor-containing tissues that are opposite in direction from those elicited by CB1 or CB2 receptor agonists. While some of these “inverse cannabimimetic effects” may be attributable to a direct antagonism of responses elicited at cannabinoid receptors by released endocannabinoids, there is evidence that this is not the only possible mechanism and that these compounds are in fact all inverse agonists that can reduce CB1 or CB2 receptor constitutive activity.

AEA activates vanilloid (TRPV1) receptors in addition to CB1 and CB2 receptors and there is also growing evidence for the existence of non-CB1, non-CB2, non-vanilloid pharmacological targets for AEA and/or other cannabinoids.8,15 There is evidence too that classic cannabinoids such as Δ9-THC, HU-211, and CBD have antioxidant properties (see below).7,16–18 In addition, Δ9-THC can act through presynaptic CB1 receptors in the CNS to inhibit glutamic acid release and that HU-211 can block glutamate (NMDA) receptors.8,18

As well as showing therapeutic potential as neuroprotective agents, Δ9-THC and CBD have other potential clinical applications, as indeed does the CB1 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist, SR141716A.7,18–20 Δ9-THC, for example, is already used in the clinic as an appetite stimulant and anti-emetic.18 In addition, this cannabinoid will most likely prove to be useful as an anti cancer drug21 and for the management of pain,22,23 and of various kinds of motor dysfunction that include the muscle spasticity, spasm, or tremor associated with multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury,24 the tics and psychiatric signs and symptoms of Tourette’s syndrome, and the dyskinesia that is produced by l-dopa in patients with Parkinson’s disease.25–27 As now discussed, one other important potential clinical application for cannabinoids, is the management of glaucoma.

CANNABINOIDS AND GLAUCOMA

In 1971, Hepler and Frank reported a 25–30% IOP lowering effect of smoking marijuana in a small number of subjects.28 The duration of action of marijuana after smoking was relatively short, about 3–4 hours, and there seemed to be a dose-response relation.28,29 Other ocular effects were observed such as conjunctival hyperaemia, reduced tear production, and change in pupil size.29 Acute systemic side effects induced by marijuana smoking included reduction of systemic blood pressure and tachycardia.4 Psychotropic effects were very variable and included euphoria or dysphoria, disruption of short term memory, cognitive impairments, sense of time distortion, reduced coordination, and sleepiness.4

An earlier report on the effect of smoked marijuana indicated the possibility of tolerance. Thus, the IOP reduction appeared to be inversely related to the duration of marijuana use.30 In contrast, Dawson et al31 reported on their ophthalmological findings comparing non-users with long term users of marijuana (10 years or more). After applying the water loading test to both groups, the reduction of IOP associated with marijuana treatment was similar between users and non-users.

Since these early observations numerous studies have been conducted confirming that different cannabinoids, including cannabidiol, cannabigerol, endogenous cannabinoids, and some synthetic cannabinoids, can reduce the IOP when administered systemically and topically (see below). Obviously, smoking of marijuana is not advisable as a long term treatment. In addition to the acute side effects, long term marijuana smoking is associated with emphysema-like lung changes, and possible increase in the frequency of lung cancer.32 Oral administration has been evaluated. However, there is a poor and variable absorption with this route,33 at least for the cannabinoid formulations that have been investigated so far.

Mechanism of IOP reduction

The mechanism of action of cannabinoids in the human eye is not fully understood. Until recently, the effect of cannabinoids on IOP was assumed to be mediated through the CNS. Studies involving unilateral topical application of cannabinoids34,35 showed a large difference between the treated and untreated eye, suggesting a localised action. The experiments of Liu et al36 revealed evidence pointing in the same direction: bolus administration of Δ9-THC into the cerebral ventricles, as well as ventriculocisternal perfusion with Δ9-THC in rabbits, in contrast with intravenous administration, did not change the IOP. Thus, the main site of action of cannabinoids on IOP is not in the central nervous system.

Pharmacological and histological studies support the direct role of ocular CB1 receptors in the IOP reduction induced by cannabinoids. Straiker et al11 detected CB1 receptors in ocular tissues of the human eye, including the ciliary epithelium, the trabecular meshwork, Schlemm’s canal, ciliary muscle, ciliary body vessels, and retina. Porcella et al10 found high levels of CB1 mRNA in the ciliary body. The anatomical distribution of cannabinoid receptors suggests a possible influence of endogenous cannabinoids on trabecular and uveoscleral aqueous humour outflow and on aqueous humour production. In addition to the proved IOP lowering effect of CB1 receptor agonists, Pate et al37 could antagonise the IOP lowering effect of CP-55,940 (a synthetic CB1 agonist) by pretreating the animals with SR 141716A (a CB1 receptor antagonist). Similarly, Song et al38 found that the IOP lowering effect of topical WIN-55,212-2 was significantly reduced by topically administered SR141716A.

Using the synthetic cannabinoid WIN-55,212-2, Chien et al39 could demonstrate an 18% reduction in the aqueous humour production in monkeys but without significant change in the trabecular outflow facility. As this percentage appeared not sufficient to account for the total IOP lowering effect, other additional mechanisms were thought to be involved.

The IOP reducing effect does not seem to be related to a systemic reduction of arterial blood pressure.40 However, a direct effect on the ciliary processes, and specifically a reduction in capillary pressure, leading to changes in aqueous humour dynamics, has been proposed.41 Green et al42 showed that Δ9-THC decreased the secretion of ciliary processes and led to a dilatation of the ocular blood vessels through a possible β adrenergic action. In addition, Sugrue43 indicated that cannabinoids may inhibit calcium influx through presynaptic channels and in this way reduce the noradrenaline release in the ciliary body, leading to a decrease in the production of aqueous humour. Porcella et al10 proposed that cannabinoids might be acting as vasodilators on blood vessels of the anterior uvea, thus improving the aqueous humour uveoscleral outflow.

Green et al44,45 postulated that some cannabinoids may influence the IOP through a prostaglandin mediated mechanism. For example, topically applied AEA is hydrolysed to arachidonic acid, which is a COX pathway precursor of prostaglandins.46,47

The topical application of the CB2 receptor agonist JWH-133 used in in vivo experiments by Laine et al48 did not have any effect on IOP compared to vehicle treatments, indicating that CB2 receptor agonists may not be involved in the regulation of IOP.

Topical application of cannabinoids

To minimise possible systemic adverse side effects and maximise the dose at the site of action, topical application would be the ideal form of administration. However, natural cannabinoid extracts as well as synthetic forms are highly lipophilic and have low aqueous solubility, creating practical difficulties for this mode of administration.

After instillation of an eye drop of any medication, loss of the instilled solution via the lacrimal drainage system and poor drug penetration results in only <5% of an applied dose reaching the intraocular tissues. The cornea is usually the major pathway for intraocular penetration of topical medications. The corneal epithelium is highly lipophilic and its penetration is a rate limiting step for lipophilic drugs. Aqueous solubility is another drug property important for efficacy of delivery, as the surface of the eye is constantly moistened by tear fluid. Additional factors affecting corneal absorption include the molecular size, charge, and degree of ionisation.49

Previous experiments with topical cannabinoid solutions involved the use of light mineral oil as a vehicle, but proved to be irritant to the human eye.50,51 Recently, different microemulsions and cyclodextrins (macrocyclic oligosaccharides) have been shown to improve the corneal penetration of cannabinoids. These formulations successfully induced an unilateral IOP lowering effect.52–58 Cyclodextrins have already been used efficiently by Porcella et al56 to administer the synthetic cannabinoid WIN-55,212-2 topically to glaucoma patients.

Neuroprotective and vascular actions of cannabinoids

In glaucoma, the final pathway leading to visual loss is the selective death of retinal ganglion cells through apoptosis. Apoptosis is initiated by axonal injury at the optic disc, either by compression and/or by ischaemia. In ischaemia, glutamate is released and activates NMDA receptors. NMDA receptor activation appears to be one of several pathways that result in apoptotic cell death. After activation of NMDA receptors there is an influx of calcium into the cells and free radicals are generated. Substances that prevent this cascade of events and inhibit the retinal ganglion cell death are currently under investigation.59

Recent studies have documented the neuroprotective properties of cannabinoids. There is evidence that Δ9-THC can inhibit glutamic acid release by increasing K+ and decreasing Ca2+ permeability and that the synthetic cannabinoid HU-211 can block glutamate (NMDA) receptors.8,9,18,59–62 These actions are mediated by presynaptic CB1 receptors. Yoles et al, using a calibrated crush injury to adult rat optic nerve (optic nerve axotomy), showed a beneficial effect of HU-211 on injury induced metabolic and electrophysiological deficits.63 However, the optic nerve crush model may not resemble the mechanisms responsible for glaucomatous nerve damage.

Classic cannabinoids such as Δ9-THC, HU-211, and CBD have antioxidant properties that are not mediated by the CB1 receptor. As a result, they can prevent neuronal death by scavenging toxic reactive oxygen species produced by overstimulation of receptors for the excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamic acid.7,16–18,64

Cannabinoids have vasorelaxant properties and so might be able to increase the ocular blood flow. The mediator endothelin-1, produced by vascular endothelial cells, has a significant role in the regulation of local circulation, producing vasoconstriction and being involved in the pathophysiological processes of ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, Raynaud’s phenomenon, ischaemic heart disease and pulmonary arterial hypertension, among others.65 The possible role of endothelin-1 in the pathogenesis of glaucoma has been suggested. For example, patients with open angle glaucoma may have an abnormal increase in plasma endothelin-1 in response to vasospastic stimuli.66,67 Mechoulam et al61 could demonstrate that 2-arachidonoylglycerol, an endogenous cannabinoid, was able to reduce endothelin induced Ca2+ mobilisation, inhibiting vasoconstriction. Thus, cannabinoids may have beneficial properties in ischaemia induced optic nerve damage.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Cannabinoids have the potential of becoming a useful treatment for glaucoma, as they seem to have neuroprotective properties and effectively reduce intraocular pressure. However, several challenges need to be overcome, including the problems associated with unwanted systemic side effects (psychotropic, reduction in systemic blood pressure), possible tolerance, and the difficulty in formulating a stable and effective topical preparation. Some cannabinoids such as HU-211 and cannabidiol do not have psycotropic effects, while maintaining their IOP lowering action, so that further research on these compounds would be desirable. Tolerance may develop after repeated use of cannabinoids.30 However, tolerance might be beneficial if it develops only or preferentially to unwanted side effects. There has been recent progress in the use of microemulsions and cyclodextrins to overcome the barriers in ocular penetration of topically applied cannabinoids.

Other possible applications of cannabinoids in ophthalmology could be explored. Age related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of blindness in the United Kingdom. Perhaps the potent antioxidant properties of the cannabinoids may be beneficial in AMD, offering a possible alternative to established antioxidant supplements.68 Cannabinoids have been shown to inhibit angiogenesis, leading to a decrease in the expression of proangiogenic factors such as VEGF.69 Evidence suggests that VEGF plays a major part in the development of choroidal neovascularisation in AMD, and clinical trials using anti-VEGF therapies are being conducted.70 The CB2 receptors are also under intense investigation for their possible immunomodulatory effects.71 The anti-inflammatory properties of CB2 receptor agonists might also prove to be of therapeutic relevance in different forms of inflammatory eye disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frankhauser M. Cannabis in der westlichen Welt. In: Grotenhermen F, ed. Cannabis und cannabinoide. 1st ed. Berlin: Verl Hans Huber, 2001:57–71.

- 2.Chalsma AL, Boyum D. Marijuana situation assesment. Washington DC: Office of National Drug Control Policy, 1994.

- 3.Schwab IR, Husted R, Liegner JT, et al. Complementary therapy assessment: Marijuana in the treatment of Glaucoma. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology, Complementary Therapy Task Force, 1999.

- 4.Grotenhermen F. Die Wirkungen von Cannabis und der Cannabinoide. In: Grotenhermen F, ed. Cannabis und cannabinoide, 1st ed. Berlin: Verl Hans Huber, 2001:75–86.

- 5.ElSohly MA. Chemical constituents of cannabis. In: Grotenhermen F, Russo E, eds. Cannabis and cannabinoids. Pharmacology, toxicology and therapeutic potential. New York: Haworth Press, 2002:27–36.

- 6.Pertwee RG. Pharmacology of cannabinoid receptor ligands. Curr Med Chem 1999;6:635–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pertwee RG. The pharmacology and therapeutic potential of cannabidiol. In: Di Marzo V, ed. Cannabinoids. New York: Landes Bioscience, 2003. (in press).

- 8.Howlett AC, Barth F, Bonner TI, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Rev 2002;54:161–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pertwee RG. Pharmacology of cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors. Pharmacol Ther 1997;74:129–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porcella A, Casellas P, Gessa GL, et al. Cannabinoid receptor CB1 mRNA is highly expressed in the rat ciliary body: implications for the antiglaucoma properties of marihuana. Mol Brain Res 1998;58:240–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Straiker A, Maguire C, Makie K, et al. Localization of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the human anterior eye and retina. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci 1999;40:2442–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pertwee RG, Ross RA. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 2002;66:101–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piomelli D, Giuffrida A, Calignano A, et al. The endocannabinoid system as a target for therapeutic drugs. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2000;21:218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pertwee RG. Inverse agonism at cannabinoid receptors. In: Esteve Foundation Symposium X. Inverse Agonism. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2003. (in press).

- 15.Pertwee RG. Novel pharmacological targets for cannabinoids. Current Neuropharmacology 2003. (in press).

- 16.Hampson AJ, Grimaldi M, Axelrod J, et al. Cannabidiol and (–)D9-tetrahydrocannabinol are neuroprotective antioxidants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95:8268–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hampson AJ, Grimaldi M, Lolic M, et al. Neuroprotective antioxidants from marijuana. In: Reactive oxygen species: from radiation to molecular biology. Ann NY Acad Sci 2000;899:274–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pertwee RG. Neuropharmacology and therapeutic potential of cannabinoids. Addiction Biology 2000;5:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barth F. Cannabinoid receptor agonists and antagonists. Expert Opinion On Therapeutic Patents 1998;8:301–13. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pertwee RG. Cannabinoid receptor ligands: clinical and neuropharmacological considerations relevant to future drug discovery and development. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 2000;9:1553–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galve-Roperh I, Sánchez C, Cortés ML, et al. Anti-tumoral action of cannabinoids: involvement of sustained ceramide accumulation and extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Nature Med 2000;6:313–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pertwee RG. Cannabinoid receptors and pain. Progress in Neurobiology 2001;63:569–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pertwee RG. Cannabinoids. In: Bountra C, Munglani R, Schmidt WK, eds. Pain current understanding, emerging therapies and novel approaches to drug discovery. New York: Marcel Dekker, 2003:683–706.

- 24.Pertwee RG. Cannabinoids and multiple sclerosis. Pharmacol Ther 2002;95:165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hemming M, Yellowlees PM. Effective treatment of Tourette’s syndrome with marijuana. J Psychopharmacol 1993;7:389–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller-Vahl KR, Kolbe H, Schneider U, et al. Cannabis in movement disorders. Forschende Komplementärmedizin 1999;6 (Suppl 3):23–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Müller-Vahl KR, Schneider U, Kolbe H, et al. Treatment of Tourette’s syndrome with delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Am J Psychiatr 1999;156:495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hepler RS, Frank IR. Marihuana smoking and intraocular pressure (letter). JAMA 1971;217:1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown B, Adams AJ, Haegerstrom-Portnoy G, et al. Pupil size after use of marijuana and alcohol. Am J Ophthalmol 1977;83:350–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flom MC, Adams AJ, Jones RT. Marijuana smoking and reduced pressure in human eyes: drug action or epiphenomenon? Invest Ophthalmol 1975;14:52–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dawson WW, Jiménez-Antillon CF, Perez M, et al. Marijuana and vision—after ten years̀ use in Costa Rica. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci 1977;16:689–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hashibe M, Ford DE, Zhang ZF. Marijuana smoking and head and neck cancer. J Clin Pharmacol 2002;42 (Suppl):103–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merritt JC, McKinnon S, Amstrong JR, et al. Oral delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol in heterogeneous glaucomas. Ann Ophthalmol 1980;12:947–50. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colasanti BK, Craig CR, Allara RD. Intraocular pressure, ocular toxicity and neurotoxicity after administration of cannabinol or cannabigerol. Exp Eye Res 1984;39:251–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colasanti BK, Powell SR, Craig CR. Intraocular pressure, ocular toxicity and neurotoxicity after administration of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol or cannabichromene. Exp Eye Res 1984;38:63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu JHK, Dacus AC. Central nervous system and peripheral mechanisms in ocular hypotensive effect of cannabinoids. Arch Ophthalmol 1987;105:245–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pate DW, Järvinen K, Urtti A, et al. Effect of the CB1 receptor antagonist SR 141716A on cannabinoids induced ocular hypotension in normotensive rabbits. Life Sci 1998;63:2181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song ZH, Slowey CA. Involvement of cannabinoids receptors in the intraocular pressure lowering effects of WIN-55,212–2. Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000;292:136–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chien FY, Wang RF, Mittag TW, et al. Effect of WIN-55,212–2, a cannabinoid receptor agonist, on aqueous humor dynamics in monkeys. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Korzyn AD. The ocular effects of cannabinoids. Gen Pharmac 1980;101:591–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDonald TF, Cheeks L, Slagle T, et al. Marijuana-derived material induced changes in monkey ciliary processes differ from those in rabbit ciliary processes. Curr Eye Res 1991;4:305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Green K, Pederson JE. Effect of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol on aqueous dynamics and ciliary body permeability in the rabbit. Exp Eye Res 1973;15:499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugrue MF. New approaches to antiglaucoma therapy. J Med Chem 1997;40:2793–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green K, Podos SM. Antagonism of arachidonic acid-induced ocular effects by Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1974;13:422–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Green K, Krease EC, McIntyre OL. Interaction between Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and indometacin. Ophthalmic Res 2001;33:217–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pate DW, Järvinen K, Urtii A, et al. Effects of topical anandamides on intraocular pressure in normotensive rabbits. Life Sci 1996;58:1849–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pate DW, Jarvinen K, Urtti A, et al. Effects of topical alpha-substituted anandamides on intraocular pressure in normotensive rabbits. Pharm Res 1997;14:1738–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laine K, Järvinen K, Järvinen T. Topically administered CB2-receptor agonist, JWH-133, does not decrease intraocular pressure (IOP) in normotensive rabbits. Life Sci 2003;72:837–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Järvinen T, Pate DW, Laine K. Cannabinoids in the treatment of glaucoma. Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2002;95:203–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Green K, Roth M. Ocular effects of topical administration of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in man. Arch Ophthalmol 1982;100:263–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jay WM, Green K. Multiple drop study of topically applied 1% delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in human eyes. Arch Ophthalmol 1983;101:591–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jarho P, Urtti A, Pate DW, et al. Increase in aqueous solubility, stability and in vivo corneal permeability of anandamide by hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin. Int J Pharm 1996;137:209–17. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jarho P, Pate DW, Brenneisen R, et al. Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin and its combination with hydroxypropyl-methylcellulose increases aqueous solubility of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Life Sci 1998;63:381–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kearse EC, Green K. Effect of vehicle upon in vivo transcorneal permeability and intracorneal content of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Curr Eye Res 2000;29:496–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Green K, Kearse EC. Ocular penetration of topical Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol from rabbit corneal or cul-de-sac application site. Curr Eye Res 2000;21:566–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Porcella A, Maxia Ch, Gessa GL, et al. The synthetic cannabinoids WIN-55,212-2 decreases the intraocular pressure in human glaucoma resistant to conventional therapies. Eur J Neurosci 2001;13:409–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laine K, Järvinen K, Mechoulam R, et al. Comparison of the enzymatic stability and intraocular pressure effects of 2-Arachidonylglycerol and noladin ether, a novel putative endocannabinoid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002;43:3216–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Naveh N, Weissman C, Muchtar S, et al. A submicron emulsion of HU-211, a synthetic cannabinoid, reduces intraocular pressure in rabbits. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2000;238:334–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levin LA. Direct and indirect approaches to neuroprotective therapy of glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Surv Ophthalmol 1999;43 (Suppl):98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shen M, Thayer SA. Cannabibinoid receptor agonists protect cultured rat hipocampal neurons from exitotoxicity. Mol Pharmacol 1998;54:459–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mechoulam R, Panikashivili D, Shohami E. Cannabinoids and brain injury: therapeutic implications. Trends Mol Med 2002;8:58–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jin KL, Mao XO, Goldsmith PC, et al. CB1 cannabinoid receptor induction in experimental stroke. Ann Neurol 2000;48:257–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoles E, Belkin M, Schwartz M. HU-211, a nonpsychotropic cannabinoid, produces short- and long-term neuroprotection after optic nerve axotomy. J Neurotrauma 1996;13:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marsicano G, Moosman B, Hermann H, et al. Neuroprotective properties of cannabinoids against oxidative stress: role of cannabinoids receptor CB1. J Neurochem 2002;80:448–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gray GA, Battistini B, Webb DJ. Endothelins are potent vasoconstrictors, and much more besides. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2000;21:38–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haeffliger IO, Meyer P, Flammer J, et al. The vascular endothelium as a regulator of the ocular circulation: a new concept in ophthalmology? Surv Ophthalmol 1994;39:123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nicolela MT, Ferrier SN, Morrison CA, et al. Effects of cold-induced vasospasm in glaucoma. The role of endothelin-1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003;44:2565–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomised, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:1417–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Casanova ML, Blázques C, Martinez-Palacio J, et al. Inhibition of skin tumor growth and angiogenesis in vivo by activation of cannabinoids receptors. J Clin Inverst 2003;111:43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.The Eye Tech Study Group. Preclinical and phase 1A clinical evaluation of an anti-VEGF pegylated aptamer (EYE001) for the treatment of exudative age-related macular degeneration. Retina 2002;22:143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zurier RB. Prospects for cannabinoids as anti-inflammatory agents. J Cell Biochem 2003;88:462–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]