Abstract

Aim: To describe the authors’ experience and that in the published literature regarding the use of corticosteroid sparing systemic immunosuppression for patients with corticosteroid dependent optic neuritis not associated with demyelinating disease.

Methods: The records of 10 patients from the authors’ clinical database, and 38 patients from the published literature with corticosteroid dependent optic neuritis, were retrospectively reviewed to determine patient demographics, diagnosis, clinical course, and outcomes. These patients had recrudescence of symptoms, such as decreased vision and pain, with attempted taper of corticosteroid. Many of these patients also suffered side effects from systemic corticosteroid use such as weight gain and uncontrolled hyperglycaemia. Antimetabolites (for example, methotrexate and azathioprine), cyclosporine and/or alkylating agents (for example, cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil) were given to enable taper of corticosteroid while effectively controlling optic neuritis.

Results: The study included 43 women and 5 men: 17 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, 12 patients with sarcoidosis, 3 with other systemic autoimmune diseases, and 16 with no clinically identifiable systemic association. 79% of all patients benefited from the use of systemic immunosuppression in that they had successful corticosteroid taper, control of inflammation, improvement in symptoms, and/or tolerance of adverse effects. Mild toxicity was common and 19% of patients, most often those taking cyclophosphamide, discontinued medication because of adverse effects. 24 of 28 (86%) patients on alkylators benefited clinically, while 20 of 29 (69%) patients on antimetabolites had clinical benefit.

Conclusion: Systemic immunosuppression may be a safer and more effective treatment alternative to chronic oral corticosteroid use in cases of corticosteroid dependent optic neuritis not associated with demyelinating disease.

Keywords: optic neuritis, corticosteroid dependent, corticosteroid sparing

Optic neuritis is most often an acute self limited inflammation of the optic nerve that resolves with or without corticosteroid therapy over the course of a few weeks to months.1 Resolution of inflammation and visual function may be partial or complete. Patients with optic neuritis are usually in their 20s to 50s, more often female, and present with symptoms such as acute visual loss, scotomas, colour vision loss, and pain with eye movement.1,2 The vast majority of cases of isolated acute optic neuritis are a manifestation of demyelinating disease, usually multiple sclerosis.1,3

A small percentage of patients have optic neuritis that is not associated with demyelinating disease. In these cases, optic neuritis is often a manifestation of an underlying systemic condition, including collagen vascular diseases, multisystem granulomatous diseases, post-vaccination syndrome, and viral or bacterial infections.1,2 In a few cases, the association with systemic disease is less clear. Various names have been given to these unusual cases of optic neuritis to differentiate them from optic neuritis associated with multiple sclerosis. For example, optic neuritis associated with an underlying collagen vascular disease without a systemic diagnosis has been termed “autoimmune optic neuritis”.4 Similarly, patients with evidence of granulomatous disease without a systemic diagnosis have been identified as having “chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuropathy”.5

Optic neuritis associated with granulomatous or collagen vascular disease is frequently corticosteroid responsive and resistant to drug taper.1 A smaller number of cases are corticosteroid resistant, requiring large doses of corticosteroid to gain the slightest improvements in visual function.6 In both examples, patients are often treated chronically with large doses of systemically administered corticosteroid. The morbidity of chronic corticosteroid treatment is well recognised and includes uncontrolled hyperglycaemia, hypertension, weight gain, oedema, osteoporosis, immunosuppression, and mood alteration.7 Indeed, adverse effects of chronic systemic corticosteroid therapy may contribute more to debility of patients than the underlying disease that the clinician is attempting to treat.8

Treatment with corticosteroid sparing systemic immunosuppressive therapy frequently has fewer long term adverse effects than chronic corticosteroid therapy.8 There are several reports in the published literature regarding corticosteroid sparing immunosuppressive therapy for corticosteroid dependent optic neuritis.4–6,9–17 However, these reports generally describe a small number of patients treated with a variety of immunosuppressive agents. Consequently, it is difficult to gain an overall impression of the efficacy of such treatment.

We describe the use of corticosteroid sparing systemic immunosuppressive therapy in a cohort of 10 patients with corticosteroid dependent optic neuritis. These patients had been managed with oral prednisone and/or intravenous methylprednisolone over an extended time period before referral, and all had suffered adverse effects as a result of the systemic corticosteroid therapy. In order to provide a more meaningful impression of the efficacy of immunosuppressive therapy we have combined our results with published data from similar cases of corticosteroid dependent optic neuritis that were similarly treated.

METHODS

We examined the clinical database of the uveitis service at the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) over a 17 year period from September 1985 until December 2002 to identify cases of corticosteroid dependent optic neuritis not associated with demyelinating disease. The OHSU Institutional Review Board gave approval for medical chart review for the purposes of this study. From our records and the published cases, we collected data which included patient demographics, diagnosis, baseline visual acuity, colour vision, presence or absence of an afferent pupillary defect, visual fields, details of corticosteroid use, adverse effects from corticosteroids, details of corticosteroid sparing agent use, adverse effects of corticosteroid sparing agent, and clinical response to therapy including final visual acuity.

A Medline search (keywords: optic neuritis, optic neuropathy AND recurrent, lupus, sarcoidosis, steroid sparing, antimetabolite, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate, cyclosporine, alkylating agent, cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil) was performed to identify published cases of corticosteroid dependent non-demyelinating optic neuritis treated with therapy other than systemic corticosteroid. From these cases we collected data as described above, as far as was possible from the information provided in the published reports. All data were then combined and analysed for evidence of clinical benefit to create an overall impression of the efficacy of corticosteroid sparing therapy.

For an initial analysis including only our patients, three treatment outcomes were defined. A “successful trial” of corticosteroid sparing therapy was strictly defined as: (1) the ability to reduce systemic corticosteroid to a daily dose of 10 mg of oral prednisone or less; (2) clinically reduced inflammation; (3) stabilisation or improvement in visual acuity or symptoms such as pain, and (4) patient tolerance of any drug related side effects. “Clinical benefit” from corticosteroid sparing therapy was defined as satisfaction of at least two, but less than four, of the above criteria. If fewer than two criteria were satisfied, treatment was considered to have “no clinical benefit”. Because of incomplete information from previously published cases, when data relating to our patients were combined with data from the literature, we defined “clinical benefit” as satisfaction of at least two of the above criteria for the entire patient group. If relevant clinical data were not presented, but the authors reported the treatment as beneficial, corticosteroid sparing therapy was also considered to have provided “clinical benefit”.

RESULTS

Ten patients (15 eyes) with corticosteroid dependent optic neuritis not associated with demyelinating disease were identified from our database. One patient (patient 8) is previously described, but is presented here with further follow up data.11 All ten patients were female. Five patients had idiopathic optic neuritis with no clinically identifiable systemic disease (patients 1–5). Three patients had sarcoidosis (patients 6–8), and two patients had systemic lupus erythematosus (patients 9 and 10). In five cases the optic neuritis was retrobulbar, and in five cases there was optic nerve head swelling. A summary of clinical information relating to these patients is found in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic features, diagnosis, previous corticosteroid therapy and side effects, dose and duration of corticosteroid sparing therapy, and outcome of therapy in ten patients with corticosteroid dependent optic neuritis

| Patient no | Age/sex/race | Diagnosis | Eye* | Most consistent corticosteroid dose, total duration of corticosteroid treatement at any dose, and indication for corticosteroid sparing agent. | Drug dose and duration | Adverse effects | Corticosteroid dose (final) | Initial visual acuity | Final visual acuity | Comment |

| 1 | 66/F/W | Optic neuritis | OD | 20 mg for 6 years; 25 pound weight gain, mood change, tremor | Mycophenylate mofetil 2000 mg daily for 16 months | Anaemia and increased blood urea nitrogen with 3000 mg daily dose | 3–10 mg | 20/25 | 20/25 | Patient reported improved mood, increased energy and improved vision with mycophenylate. |

| 2 | 52/F/W | Optic neuritis | OU | 15 mg for 18 months; 35 pound weight gain | Cyclophosphamide 125 mg by mouth daily for 13 months | Mild anaemia | 0 mg | OD:HM OS:20/40 | OD:NLP OS:20/30 | Optic nerve biopsy pathology showed non-specific inflammation. |

| 3 | 25/F/W | Optic neuritis | OU | 20 mg for 6 months; 25 pound weight gain, labile mood | Methotrexate 20 mg weekly for 6 months | Headache, fatigue | 17–40 mg | OD:CF OS:CF | OD:20/20 OS:20/20 | Continued flares of optic neuritis despite therapy. |

| Cyclosporine 200 mg daily in combination with methotrexate 20 mg weekly for 1 month | Hypertension, paresthesias | |||||||||

| Mycophenylate mofetil 3000 mg daily for 3 months | Headache | |||||||||

| 4 | 62/F/W | Optic neuritis with hearing loss and cranial neuropathies (VII/VI) | OS | 60 mg for 14 months; 55 pound weight gain, oedema, diabetes, osteoporosis, palpitations, bruising | Azathioprine 200 mg daily for 8 months | Hair loss | Patient discontinued all medications | 20/60 | 20/60 | Patient reported increased energy and stabilisation of weight on azathioprine but was poorly compliant. |

| 5 | 29/F/W | Optic neuritis | OU | 30 mg for 2 years; 25 pound weight gain, mood changes, oedema, arthralgia | Methotrexate 20 mg weekly for 4 months | None | 0–5 mg | OD:20/HM OS: 20/20 | OD: 20/HM OS: 20/20 | Cranial neuropathy (VI) concurrent with optic neuritis. Patient is deceased (cause of death undetermined). |

| Azathioprine 100 mg daily for 6 weeks | Headache, hypertension, nausea | |||||||||

| Mycophenylate mofetil 500 mg daily for 3 weeks | Nausea, headache | |||||||||

| Cyclophosphamide 200 mg daily for 42 months | Nausea, haemorrhagic cystitis | |||||||||

| 6 | 60/F/W | Sarcoidosis | OD | 30–60 mg for 35 years; diabetes, weight gain, non-healing wounds | Methotrexate 7.5 mg weekly for 7 months | None | 20 mg | CF | CF | APD better by 0.9 log units. Patient has severe lung disease. |

| 7 | 56/F/W | Sarcoidosis | OD | 60 mg for at least 4 months; 35 pound weight gain, cushingoid, weakness, labile mood, decreased energy | Azathioprine 150 mg daily for 55 months | Mild hair loss | 0 mg | 20/30 | 20/20 | Patient has restarted corticosteroid therapy per her internist since her last visit for active lung disease. |

| 8 | 55/F/W | Sarcoidosis | OU | 40–60 mg for 2 years; 20 pound weight gain, palpitations, sleep disruption, labile mood | Methotrexate 20 mg weekly for 42 months | None | 10–20 mg | OD:20/20 | OD:CF | |

| Azathioprine 50 mg daily for 1 week | ?Fever, irritation | OS:20/40 | OS:20/40 | |||||||

| Mycophenylate mofetil 2000 mg daily for 5 months | Paresthesias | |||||||||

| Hydroxycholorquine 200 mg daily and methotrexate 20 mg weekly for 2 months | None | |||||||||

| 9 | 53/F/W | Systemic lupus erythematosus | OU | 60 mg for 10 years intermittently; diabetes, cushingoid | Cyclophosphamide 1650 mg IV every six weeks for 12 months | Pneumonitis, nausea | 4 mg | OD:NLP OS:LP | OD:20/30 OS: 20/25 | |

| 10 | 50/F/H | Systemic lupus erythematosus, thyroid related immune orbitopathy | OD | 20 mg for 8 years; 60 pound weight gain, no benefit from corticosteroid | Mycophenylate mofetil 2000 mg daily for 3 months | Hair loss | 0 mg | OD:20/HM OS:20/40 | OD:20/150 OS:20/20 | Patient has a history of repaired retinal detachment OD and radiation therapy to both orbits. |

F, female; W, white; H, Hispanic; OD, right eye; OS, left eye; OU, both eyes; IV, intravenous; HM, hand motions; CF, counting fingers; LP, light perception; NLP, no light perception.

*Uninvolved eyes are not detailed in this table.

Each of our patients had been given a comprehensive ophthalmic assessment including ocular and systemic history, measurement of visual acuity, colour vision testing, evaluation of the pupils including testing for an afferent pupillary defect, visual field testing, and dilated posterior segment examination. Visual field testing revealed varied patterns of visual field loss from essentially normal to paracentral scotomas and constricted peripheral fields. Additionally, every patient underwent imaging studies including magnetic resonance imaging of the head to rule out white matter lesions consistent with multiple sclerosis. Other imaging studies including chest x ray and, in some cases, computed tomography were performed if indicated to support a diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Diagnostic procedures such as cerebrospinal fluid analysis to identify IgG oligoclonal bands and tissue biopsy with histopathology for non-caseating granulomas were also performed in several patients to assist in the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis or sarcoidosis, respectively. Each patient also had laboratory work including complete blood examination with differential, serum metabolic panel, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and where appropriate, testing for autoantibodies.

Optic neuritis was successfully brought into remission (improvement in symptoms, visual acuity, and clinically apparent inflammation) in these 10 patients after systemic corticosteroid therapy. However, all patients suffered recrudescence of the inflammation when taper was attempted. In addition, each of these 10 patients had experienced adverse effects from systemic corticosteroid therapy.

A trial of corticosteroid sparing therapy was started after unsuccessful attempts to taper systemic corticosteroids, which had been previously administered over a period of 3–72 months. Corticosteroid sparing agents that were used included methotrexate (n = 4), mycophenolate mofetil (n = 5), azathioprine (n = 4), cyclosporine (n = 1), and cyclophosphamide (n = 3). Treatment was selected, prescribed, and monitored in accordance with published guidelines.18 Patients were followed subsequently for an average of 17.8 months. In some cases it was necessary to change drugs because of lack of effect or drug related complications.

Overall, five of 10 patients (patients 1, 2, 7, 9, and 10) met all of the criteria for a successful trial of corticosteroid sparing therapy. These patients were treated with cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, or mycophenylate mofetil. Three additional patients (patients 4, 5, and 6) showed clinical benefit, but did not meet all four criteria. These patients were treated with one or more of the same three drugs or with methotrexate. Resolution or improvement of chronic corticosteroid induced adverse effects was reported in all eight patients who had clinical benefit from therapy. Two patients (patients 3 and 8) have not yet responded favourably to initial therapeutic trials with multiple agents and are undergoing trials with other agents.

One patient (patient 5) switched from initial corticosteroid sparing therapy three times either because of intolerable side effects or because of lack of efficacy. Her disease was eventually controlled with cyclophosphamide that was later discontinued because she developed haemorrhagic cystitis. Another patient (patient 7) was able to discontinue immunosuppressive therapy completely without recurrence of optic neuritis after 55 months of treatment with azathioprine. However, she has subsequently developed active pulmonary sarcoidosis and is currently being treated by her internist with systemic corticosteroids.

Every patient who took mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, or cyclophosphamide reported adverse effects. Three patients had to stop or switch therapy because of adverse effects. One patient (patient 3) developed hypertension after treatment with cyclosporine. Two patients (patients 5 and 9), who both were treated with cyclophosphamide, developed hemorrhagic cystitis and pneumonitis, respectively. Only one patient (patient 3) reported headache and fatigue on methotrexate, whereas other patients using this agent were free of adverse effects.

A Medline search identified 11 papers discussing 38 patients (67 eyes) with corticosteroid dependent optic neuritis not associated with demyelinating disease that was treated with corticosteroid sparing therapy. Thirty three of these 38 patients were female. Fifteen patients had systemic lupus erythematosus, nine had sarcoidosis, and one had mixed connective tissue disease. One had orbital pseudotumour associated with optic neuritis, and another had neuroretinitis. In 11 patients there was no clinical diagnosis of a systemic disease associated with the optic neuritis. An additional paper by Kidd et al recently reported at least two patients with “chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuropathy” managed with corticosteroid sparing immunosuppression, but sufficient detail was not available in the report to merit inclusion in these results.5 Available clinical data from these cases are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

| First author | Year | Age/sex | Diagnosis | Eye* | Time and dose of corticosteroid or other therapy | Indication for corticosteroid sparing agent | Drug, dose, and duration (if reported) | Adverse effects | Corticosteroid dose (final) | Initial visual acuity | Final visual acuity | Comment |

| Siatkowski RM | 2001 | 32 F | Systemic lupus erythematosus | OU | 6 months of corticosteroid | 3 relapses on corticosteroid | Monthly IV cyclophosphamide for 7 months, no relapses while on therapy | Unknown | Unknown | OD:LP OS:20/15 | OD:5/200 OS:20/200 | Patient discontinued cyclophosphamide because she desired to become pregnant. |

| 42 F | OD | Unknown | Unknown | Azathioprine for 16 months, then monthly IV cyclophosphamide | Unknown | 20 mg | OD:20/200 | OD:20/40 | ||||

| Frohman LP | 2001 | 51 F | Systemic lupus erythematosus | OU | 5mg/2.5 mg and hydroxychloroquine 400 mg daily | Unknown | Methotrexate 15 mg weekly | Unknown | 0 mg | OD:LP OS:20/70 | OD:20/20 OS:20/20 | |

| Galindo-Rodriguez G | 1999 | 41 F | Systemic lupus erythematosus | OU | 100 mg for 2 months | Disease refractory to corticosteroid and/or oral immunosuppression | Cyclophosphamide 0.5–1.0 gm/m2 IV on 2 consecutive days monthly. Mean duration 5 months | All patients had side effects: 7 patients with urinary tract infections, 3 patients with upper respiratory infections, 2 patients with herpes zoster infections, 1 patient with pneumonia, 4 patients with oral candidaisis, 5 patients with hair loss, 1 patient with cutaneous abcess. | Unknown | OD:20/40 OS:HM | OD:20/30 OS:20/30 | Only 3 patients discontinued treatment and this was secondary to nausea and vomiting. |

| 35 F | OU | 100 mg for 4 months | OD:CF OS:CF | OD:20/50 OS:20/100 | ||||||||

| 36 F | OU | 60 mg for 8 months and azathioprine 150 mg for 9 months and cyclophosphamide by mouth for 12 months | OD:CF OS:CF | OD:20/50 OS:20/20 | ||||||||

| 18 F | OU | 60 mg for 24 months and azathioprine 100 mg for 24 months and cyclophosphamide by mouth for 6 months | OD:NLP OS:CF | OD:CF OS:20/200 | ||||||||

| 44 F | OU | 100 mg for 4 months and azathioprine 150 mg for 20 months and cyclophosphamide by mouth for 4 months | OD:CF OS:CF | OD:20/25 OS:20/30 | ||||||||

| 55 F | OU | 100 mg for 2 months | OD:20/70 OS:20/70 | OD:20/20 OS:20/20 | ||||||||

| 43 F | OU | 100 mg for 2 months | OD:CF OS:CF | OD:20/60 OS:20/80 | ||||||||

| 17 F | OU | 100 mg for 3 months and azathioprine 100 mg for 2 months | OD:CF OS:CF | OD:20/20 OS:20/25 | ||||||||

| 32 F | OU | 150 mg for 4 months | OD:HM OS:20/40 | OD:HM OS:20/60 | ||||||||

| 30 F | OU | 60 mg for 1 month | OD:20/20 OS:20/25 | OD:20/30 OS:20/40 | ||||||||

| Rosenbaum JT | 1997 | 32 F | Systemic lupus erythematosus | OS | Unknown doses of corticosteroid and azathioprine | Unknown | IV cyclophosphamide for 28 months | Unknown | Unknown | OD: HM | OD: 20/20 | |

| 56 F | OD | Unknown dose | IV cyclophosphamide for 2 months | OD: LP | OD: 20/30 | |||||||

| Maust HA | 2003 | 35F | Sarcoidosis | OU | 20–40 mg daily for 5 months | Insomnia, anxiety | Methotrexate 2.5–10 mg weekly for 30 months | Leukopenia in one patient | 0 mg | OD:CF OS: 20/400 | OD:20/50 OS: 20/20 | |

| 41F | OD | 10–40 mg daily for 2 months | Hyperglycaemia | Methotrexate 2.5–10 mg weekly for 36 months | 18 mg | OD: CF | OD: 20/30 | |||||

| 47F | OU | 10–80 mg daily for 8 months | Mood swings, insomnia, weight gain, depression, alopecia | Methotrexate 7.5–15 mg weekly for 23 months | 0 mg | OD: HM OS: 20/20 | OD: NLP OS: 20/25 | |||||

| Bielory L | 1991 | 48 F | Orbital pseudotumor | OS | Unknown dose | 4 patients with weight gain, 2 patients with uncontrolled hyperglycaemia, 2 patients with hypertension | Cyclosporine A 2 mg/kg/day for an average of 16.5 months | Hypercholesterolaemia and hirsutism in unknown number of patients | Unclear | OS: 20/400 | OS: 20/20 | Weight gain, diabetes and hypertension resolved in all patients after corticosteroid dose was tapered. |

| 38 M | Sarcoidosis | OU | OD:20/20 OS: 20/25 | “Normal acuity” | ||||||||

| 56 F | OU | OD:20/200 OS:20/200 | OD:CF OS:20/400 | |||||||||

| 25 M | OU | OD:20/40 OS:20/200 | OD:20/30 OS:20/200 | |||||||||

| Gelwan MJ | 1988 | 45 F | Sarcoidosis | OU | Unknown dose | Hypertension and diabetes | 4500 cGy of radiation then azathioprine 800 mg daily for 8 months | Unknown | 10 mg | OD:20/40 OS:20/100 | OD:20/25 OS:20/20 | |

| 32 M | OU | Diabetes, cushingoid, glaucoma | 4500 cGy of radiation then azathioprine 200 mg daily for 5 months | None | 10 mg every other day | OD:20/40 OS:NLP | OD:20/60 OS:NLP | Diabetes and cushingoid features resolved | ||||

| 20 M | OU | Cushingoid | 4880 cGy of radiation then chlorambucil 6 mg daily for 6 months | Unknown | 7.5 mg | OD:20/20 OS:20/200 | OD:20/20 OS:CF | Poor compliance | ||||

| Gressel MG | 1983 | 21 F | Mixed connective tissue disease | OU | 40 mg daily | Cushingoid | Azathioprine for 7 months, then oral cyclophosphamide 100 mg daily for 5 months then chlorambucil 4 mg daily | Hemorrhagic cystitis and leukopenia on cyclophos-phamide | Unknown | OD:20/40 OS:20/25 | Unknown | Rapid progression despite treatment |

| Purvin A | 1994 | 32 F | Neuroretinitis | OU | Unknown dose | Inefficacy | Azathioprine for 3 years | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | OD:20/20 OS:20/80 | Recurrent attacks suppressed with azathioprine |

| Kupersmith MJ | 1988 | 44 F | Autoimmune optic neuropathy | OD | 100 mg daily for 12 months | Corticosteroid intolerance or inefficacy | Chlorambucil 6 mg daily for 6.5 years | None | “lower” | OD: LP OS: 20/20 | OD: 20/25 OS: 20/20 | |

| 42 F | OU | 100 mg daily for 4 months | Chlorambucil 6 mg daily for 6.5 years | None | “lower” | OD: NLP OS: LP | OD: NLP OS: 20/20 | |||||

| 26 F | OU | 100 mg daily for 3 months | Cyclophosphamide 150 mg and Azathioprine 100 mg daily for 5.5 years | Pneumocystis pneumonia | “reduced” | ODHM OS: HM | OD: 20/25 OS: 20/25 | |||||

| 26 F | OU | 100 mg daily for 1.5 months | Chlorambucil 6 mg and Azathioprine 75 mg daily for 6.5 years | Herpetic keratitis | “lower” | OD: CF OS: 20/300 | OD: 20/25 OS: 20/300 | |||||

| 56 F | OD | Unknown dose | Azathioprine 125 mg daily for 6 months | None | 30 mg | OD: 20/400 OS: 20/20 | OD: 20/30 OS: 20/20 | |||||

| 47 F | OS | 20 mg daily for 1 months | Azathioprine 50 mg daily for 1 week | None | 60 mg | OD: 20/20 OS: 20/400 | OD: 20/20 OS: 20/40 | Patient refused treatment after one week. | ||||

| 45 M | OU | 60 mg daily for 1 months | Chlorambucil 8 mg daily for 18 months | None | 5 mg | OD: LP OS: NLP | OD: 20/50 OS: LP | |||||

| Azathioprine 200 mg daily | ||||||||||||

| Chlorambucil 6 mg daily for over three years | ||||||||||||

| 27 F | OU | 80 mg daily for 1 months | Chlorambucil 6 mg daily for 18 months | Agranulocytosis and sepsis | 10 mg | OD: 20/60 OS: NLP | OD: 20/20 OS: CF | Chlorambucil disontinued because of episode of sepsis. | ||||

| Azathioprine 200 mg daily for 4 years | None | |||||||||||

| Dutton JJ | 1982 | 44 F | Autoimmune retrobulbar optic neuritis | OU | Unknown dose | Unknown | Chlorambucil 6 mg daily for 2 years | Unknown | 0 mg | OD:20/80 OS:20/25 | OD:20/20 OS:20/20 | |

| 26 F | OU | Cushingoid, depression | Chlorambucil 6 mg daily and azathioprine 75 mg daily for 1 year | OD:CF OS:CF | OD:20/30 OS:20/300 | |||||||

| 42 F | OD | Unknown | Chlorambucil 6 mg daily for 6 months | LP | 20/20 |

F, female; M, male; OD, right eye; OS, left eye; OU, both eyes; IV, intravenous; NLP, no light perception; HM, hand motion; CF, count fingers; LP, light perception.

*Uninvolved eyes are not detailed in this table.

Thirty of the 38 patients (79%) in the published literature showed clinical benefit from corticosteroid sparing therapy. Five additional patients (14%) had systemic benefit from corticosteroid sparing therapy, but no visual benefit. Three patients (8%) had no benefit. Medications prescribed for these patients included azathioprine (n = 12), methotrexate (n = 4), cyclosporine (n = 4), cyclophosphamide (n = 16), and chlorambucil (n = 10). Mean follow up time on treatment was 21.3 months for patients whose follow up was documented. Five publications reported adverse effects in 15 of 23 (65%) patients. In those reports, four (15%) patients discontinued therapy secondary to adverse effects, including three patients treated with cyclophosphamide and one patient treated with chlorambucil. A sixth paper reported complications, but did not indicate patient numbers and therefore is not represented in these figures.

When data from both groups were combined, 48 patients with an average age of 40.3 years, 43 of whom were women, were identified. Of these 48 individuals, 17 patients had systemic lupus erythematosus, 12 patients had sarcoidosis, and three patients had been given other systemic or ocular diagnoses. Sixteen patients were not clinically diagnosed with systemic disease. During the course of therapy, patients were treated with cyclophosphamide (n = 19), azathioprine (n = 16), chlorambucil (n = 10), cyclosporine (n = 5), methotrexate (n = 8), and mycophenolate mofetil (n = 5).

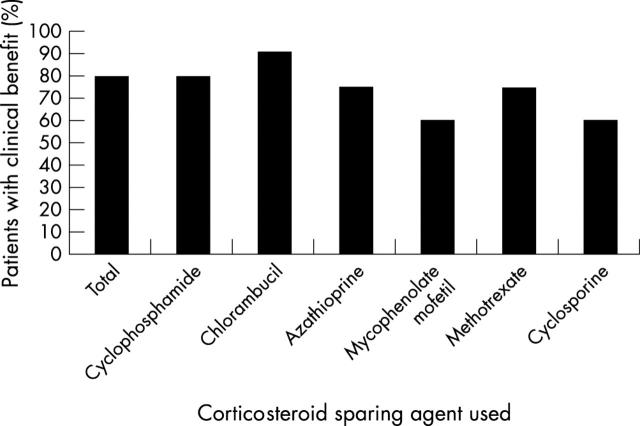

Thirty eight of 48 patients with optic neuritis (79%) showed clinical benefit from corticosteroid sparing therapy, as illustrated in figure 1. Eleven of 29 patients were able to stop corticosteroid therapy completely. Data on final corticosteroid dosing were not always available. Of these 11 individuals, five patients were treated with alkylating agents, and seven patients were treated with antimetabolites. Twenty two of 38 (58%) of patients had improvement or resolution of corticosteroid induced adverse effects.

Figure 1.

Thirty eight of 48 patients with optic neuritis (79%) showed clinical benefit from corticosteroid sparing therapy. Fifteen of 19 (79%) patients taking cyclophosphamide and nine of 10 (90%) of patients taking chlorambucil showed benefit from therapy. Twelve of 16 (75%) of patients on azathioprine, three of five (60%) on mycophenolate mofetil, and six of eight (75%) patients on methotrexate also showed benefit from therapy. Two of five patients (60%) who were treated with cyclosporine showed benefit from therapy. Several patients took more than one immunosuppressive agent.

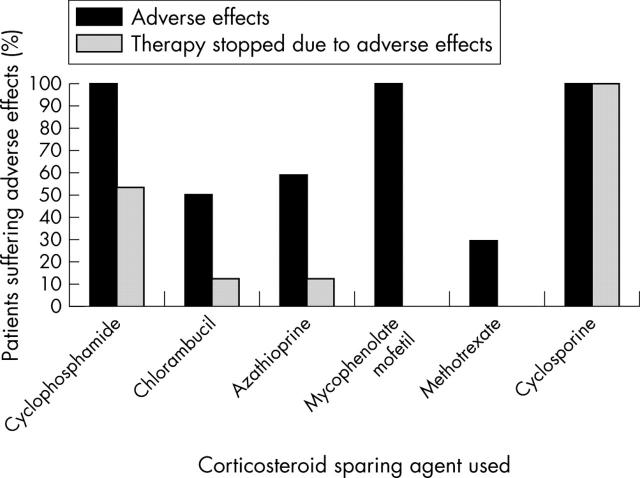

Of the 37 cases where data regarding adverse effects from corticosteroid sparing systemic immunosuppression were available, 24 patients experienced adverse effects, as shown in figure 2. However, the majority of these effects were mild, and only seven (19%) patients (five of whom were on cyclophosphamide) ceased therapy because of adverse effects. Ten of 48 patients (21%) stopped or switched therapy because of lack of efficacy. Of those patients, seven individuals were treated with azathioprine. The other three patients were treated at various times with methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine.

Figure 2.

Twenty four of 37 patients experienced adverse effects from corticosteroid sparing therapy. Fifteen of 15 (100%) of patients on cyclophosphamide, three of six (50%) of patients on chlorambucil, seven of 12 (58%) of patients on azathioprine, five of five (100%) of patients on mycophenolate mofetil, two of seven (29%) of patients on methotrexate and one of one (100%) of patients on cyclosporine reportedly suffered adverse effects. Several patients took more than one immunosuppressive agent.

DISCUSSION

Treatment of patients with corticosteroid dependent optic neuritis not associated with demyelination is challenging because one must select a treatment that is aggressive enough to minimise visual loss while avoiding adverse effects that may be serious. Clinicians may be reticent to place these frequently young patients on potentially harmful agents such as cyclophosphamide. However, the data presented here offer justification for using such agents not only to treat corticosteroid dependent optic neuritis effectively, but also to avoid the morbidity associated with chronic systemic corticosteroid use. A few patients may experience a relentless progression of their disease despite aggressive treatment; it is likely that these patients are underrepresented in the published literature because of a bias toward publication of cases where treatment was successful.

Many patients with non-demyelinating corticosteroid dependent optic neuritis have an associated underlying systemic disease. Decisions regarding which immunosuppressive agent to use should include consideration of known data regarding the efficacy of certain agents with different systemic diseases. For example, alkylating agents such as cyclophosphamide are known to be particularly effective in treating nephritis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.19 Additionally, not all patients may be reasonably expected to discontinue systemic corticosteroid therapy completely because of a systemic diagnosis. For example, patients with sarcoidosis tend to need periodic systemic corticosteroid to control active lung disease. Clinically useful guidelines regarding corticosteroid sparing immunosuppression for ocular inflammatory disease have been recently published as recommendations from an expert panel,18 although this panel did not specifically consider optic neuropathy. Treatment with some immunosuppressive agents is relatively contraindicated with certain diagnoses. For example, tumour necrosis factor blocking drugs such as infliximab and etanercept should probably not be used routinely to treat inflammatory disease with neurological manifestations.20 Indeed, treatment with these agents has been associated with induction of demyelinating optic neuritis and drug induced lupus.21–23

This study, combining data from our clinical experience with data from previous publications, may offer some conclusions about the efficacy of corticosteroid sparing therapy for optic neuritis not associated with demyelinating disease. On the surface, the results suggest that alkylating agents have a higher success rate in treating this challenging subset of patients. However, when the data are re-examined from the standpoint of successful treatment based on diagnosis, the superiority of alkylating agents is not as clear. Fifteen of 17 (88%) patients diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus were treated with alkylating agents. Two (13%) of those patients were considered treatment failures. Only one of the 12 patients diagnosed with sarcoidosis was treated with alkylating agents; and yet, the treatment failure rate for this group was similar (8%). This again illustrates the fact that systemic diagnosis should guide the choice of corticosteroid sparing therapy. Although alkylating agents appear to be efficacious in cases of optic neuritis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, less potent agents such as antimetabolites appear to do just as well in cases of sarcoidosis associated optic neuritis.

Twelve of the 16 patients who were not clinically diagnosed with a systemic disease were also treated with alkylating agents. Only one of these 16 cases (6%) was considered a treatment failure. In these cases, a clearly diagnosed systemic disease was not available to guide treatment. In four cases, subtle laboratory or clinical findings suggestive of diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus or Wegener’s granulomatosis were used to guide treatment choices. However, in the majority of cases no diagnostic hints were available. Combined data for drug efficacy are perhaps most useful in cases where no systemic disease has been diagnosed.

A favourable treatment response to alkylating agents must be weighed against the more frequent incidence of adverse effects that may necessitate discontinuation of these drugs. Although less often efficacious, antimetabolites offer clinical benefit to many patients. Antimetabolites are associated with a lower incidence of adverse effects and these effects tend to be less severe than those seen with alkylating agents. It therefore seems reasonable to consider antimetabolites before alkylating agents for patients whose systemic diagnosis is not known. Choice of treatment in these cases can also be helped by published guidelines on corticosteroid sparing immunosuppression.18

Without standardised protocols for treatment, monitoring, follow up, and data reporting, this study, involving retrospective data collection from our medical files and review of cases described in the literature, has obvious limitations. As mentioned above, there may be a bias toward publication of cases where treatment with systemic immunosuppression was successful. However, a clear majority of individuals in our unselected patient group, as well as those cases published in the literature, showed clinical benefit from corticosteroid sparing therapy. Corticosteroid sparing therapy should therefore be considered in cases of corticosteroid dependent optic neuritis not associated with demyelinating disease.

Research support: J Smith is supported by a Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award. J Rosenbaum is supported by Research to Prevent Blindness and the Rosenfeld Family Trust.

Proprietary interests: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller NR, Newman NJ. Walsh, ed. Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology 5th ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1997;1:599–648.

- 2.Optic neuritis study group. The clinical profile of optic neuritis: experience of the optic neuritis treatment trial. Arch Ophthalmol 1991;109:1673–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez M, Silva A, Cross SA, et al. Optic neuritis: a population-based study in Olmstead County, Minnesota. Neurology 1995;45:244–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutton JJ, Burde RM, Klingele TG. Autoimmune retrobulbar optic neuritis. Am J Ophthalmol 1982;94:11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kidd D, Burton B, Plant GT, et al. Chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuropathy (CRION). Brain 2003;126:276–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galindo-Rodriguez G, Anvina-Zubieta JA, Pizarro S, et al. Cyclophosphamide pulse therapy in optic neuritis due to systemic lupus erythematosus: an open trial. Am J Med 1999;106:65–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanbury RM, Graham EM. Systemic corticosteroid therapy—side effects and their management. Br J Ophthalmol 1998;82:704–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamesis RR, Rodriguez A, Christen WG, et al. Systemic drug toxicity trends in immunosuppressive therapy of immune and inflammatory ocular disease. Ophthalmology 1996;103:768–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siatkowski RM, Scott IU, Verm AM, et al. Optic neuropathy and chiasmopathy in the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Neuroophthalmol 2001;21:193–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frohman LP, Frieman BJ, Wolansky L. Reversible blindness resulting from optic chiasmitis secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus. J Neuroophthalmol 2001;21:18–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenbaum JT, Simpson J, Neuwelt CM. Successful treatment of optic neuropathy in association with systemic lupus erythematosus using intravenous cyclophosphamide. Br J Ophthalmol 1997;81:130–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Purvin VA, Chioran G. Recurrent neuroretinitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1994;112:365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bielory L, Frohman LP. Low-dose cyclosporine therapy of granulomatous optic neuropathy and orbitopathy. Ophthalmology 1991;98:1732–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelwan MJ, Kellen RI, Burde RM, et al. Sarcoidosis of the anterior visual pathway: successes and failures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988;51:1473–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gressel MG, Tomsak RL. Recurrent bilateral optic neuropathy in mixed connective tissue disease. J Clin Neuroophthalmol 1983;3:101–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kupersmith MJ, Burde RM, Warren FA, et al. Autoimmune optic neuropathy: evaluation and treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988;51:1381–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maust HA, Foroozan R, Sergott RC, et al. Use of methotrexate in sarcoid-associated optic neuropathy. Ophthalmology 2003;110:559–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jabs DA, Rosenbaum JT, Foster CS, et al. Guidelines for the use of immunosuppressive drugs in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders: recommendations of an expert panel. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;130:492–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takada K, Illei GG, Boumpas DT. Cyclophosphamide for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2001;10:154–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Laken CJ, Lems WF, van Soesbergen RM, et al. Paraplegia in a patient receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: comment on the article by Mohan et al. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:269–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohan N, Edwards ET, Cupps TR, et al. Demyelination occurring during anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy for inflammatory arthritides. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2862–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Favalli EG, Sinigaglia L, Varenna M, et al. Drug-induced lupus following treatment with infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis. Lupus 2002;11:753–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Debandt M, Vittecoq O, Descamps V, et al. Anti-TNF-alpha-induced systemic lupus syndrome. Clin Rheumatol 2003;22:56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]