Intravitreal triamcinolone injection is a safe and effective treatment for cystoid macular oedema (CMO) caused by uveitis, 1 diabetic maculopathy, 2 central retinal vein occlusion, 3 and pseudophakic CMO. 4 Potential risks include glaucoma, cataract, retinal detachment, and endophthalmitis.

We present a case of pseudohypopyon and sterile endophthalmitis following intravitreal triamcinolone injection for the treatment of pseudophakic CMO.

Case report

An 88 year old woman underwent phacoemulsification surgery which was complicated by posterior capsule rupture. Anterior vitrectomy with implantation of a silicone intraocular lens into the sulcus was performed. Postoperatively, CMO developed. This failed to respond to treatment with topical dexamethasone, topical ketorolac, and posterior sub-Tenon triamcinolone injection, limiting visual acuity to 6/24 at 7 months following the cataract surgery.

An intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide (4 mg in 0.1 ml) (Kenalog, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Middlesex, UK) was administered through the pars plana with a 30 gauge needle using a sterile technique.

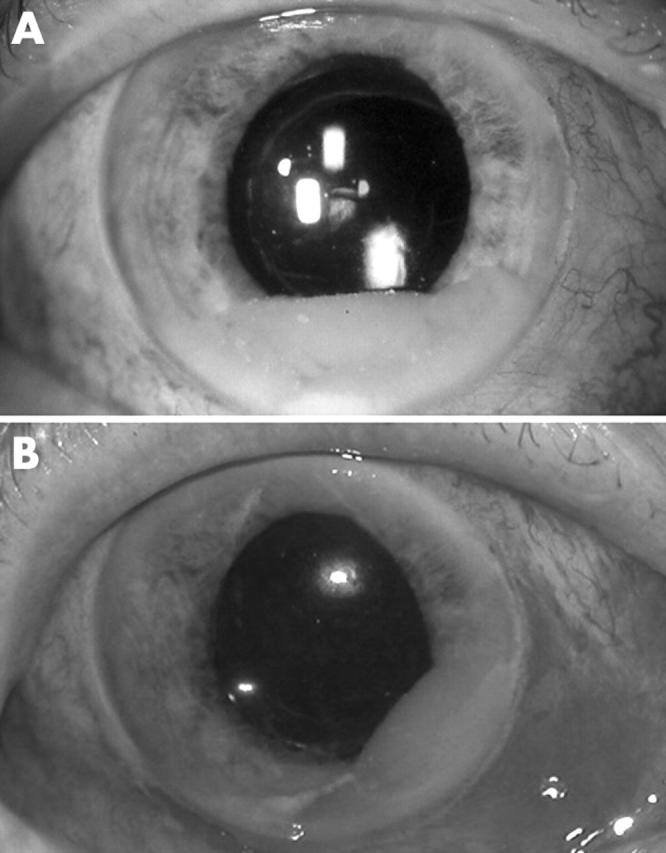

Three days later, the patient reported painless loss of vision which had developed immediately after the injection. The visual acuity was hand movements. There was minimal conjunctival injection and the cornea was clear. A 3 mm pseudohypopyon consisting of refractile crystalline particles was visible in the anterior chamber (fig 1A ), associated with 3+ anterior chamber cells (or particles). Severe vitreous haze prevented visualisation of the retina.

Figure 1.

Anterior segment photographs. (A) Pseudohypopyon composed of crystalline triamcinolone particles. (B) Recurrence of pseudohypopyon 1 day after complete surgical evacuation and injection of intravitreal antibiotics. The position of the hypopyon was gravity dependent and shifted with changes in the patient’s head position.

Because an infectious endophthalmitis could not be excluded, the patient was treated with intravitreal injections of ceftazidime and vancomycin. Vitreous and aqueous taps were performed and the pseudohypopyon was completely aspirated from the anterior chamber.

The following day, a 2 mm pseudohypopyon had reformed. The position of the pseudohypopyon was gravity dependent and shifted with changes in head position (fig 1B ).

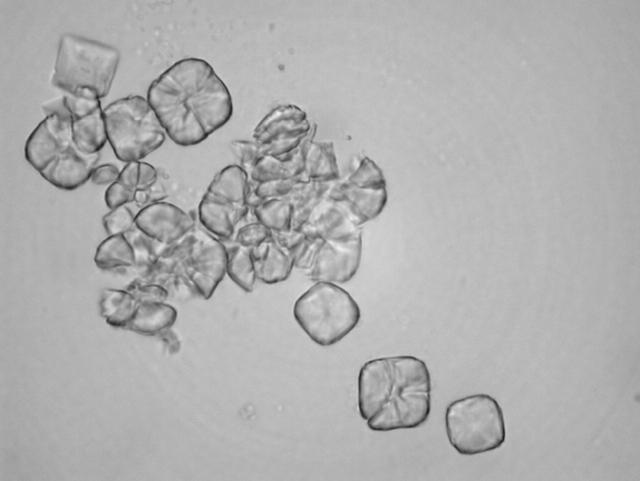

Aqueous and vitreous cultures were negative. Microscopy of the aspirated pseudohypopyon showed triamcinolone particles with no cells present (fig 2 ).

Figure 2.

Smear from aspirate of pseudohypopyon showing multiple triamcinolone crystals.

The pseudohypopyon, vitreous haze, and CMO (as demonstrated on optical coherence tomography) resolved over 6 weeks. The visual acuity recovered to 6/12.

Comment

Sutter and Gillies reported four cases of pseudoendophthalmitis characterised by painless visual loss caused by severe vitreous haze developing immediately or soon after intravitreal triamcinolone injection. 5 The triamcinolone was dispersed throughout the vitreous rather than forming a discrete mass as is usually observed after injection. They speculated that this dispersion was due to partial “jamming” of crystalline triamcinolone in the barrel of the 30 gauge needle during injection, resulting in spraying of the drug into the vitreous at high velocity, and leading to formation of a diffuse vitreous suspension. It is possible that this tendency to dispersion may be reduced by using a 27 gauge needle.

Hypopyon associated with non-infectious endophthalmitis following intravitreal triamcinolone injection has been described 6 ; however, the “pseudo” hypopyon is a unique feature of our case and is due to the presence of a posterior capsule defect enabling the passage of triamcinolone from the vitreous cavity into the anterior chamber. Presumably, the triamcinolone crystals are carried into the anterior chamber by currents generated by saccadic eye movements in the partially vitrectomised vitreous cavity.

The pseudohypopyon was distinguishable from an infective or inflammatory hypopyon by its ground glass appearance, the presence of refractile particles, and its shifting position, which was dependent upon the patient’s head position. The pseudohypopon resolved spontaneously and was not associated with any apparent toxic effects.

The absence of ocular pain, photophobia, ciliary injection, or iris vessel dilation suggests a non-inflammatory response and perhaps it would be appropriate to monitor such patients closely rather than administering intravitreal antibiotics.

References

- 1. Young S, Larkin G, Branley M, et al. Safety and efficacy of intravitreal triamcinolone for cystoid macular oedema in uveitis. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2001;29:2–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martidis A, Duker JS, Greenberg PB, et al. Intravitreal triamcinolone for refractory diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2002;109:920–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greenberg PB, Martidis A, Rogers AH, et al. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for macular oedema due to central retinal vein occlusion. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:247–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Conway MD, Canakis C, Livir-Rallatos C, et al. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for refractory chronic pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sutter FK, Gillies MC. Pseudo-endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection of triamcinolone. Br J Ophthalmol 2003;87:972–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roth DB, Chieh J, Spirn MJ, et al. Noninfectious endophthalmitis associated with intravitreal triamcinolone injection. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:1279–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]