Abstract

Aim: To characterise periorbital immune cells (stages, kinetics) in active and inactive thyroid associated ophthalmopathy (A-TAO; I-TAO).

Methods: In orbital tissue cryosections of patients with A-TAO (n = 15), I-TAO (n = 11), and healthy controls (n = 14), adipose and fibrovascular areas were evaluated for MHC II+ cells, CD45+ total leukocytes, myeloid cells (CD33+ monocytes; CD14+ macrophages; mature RFD7+ macrophages; RFD1+ dendritic cells (DCs)), and lymphoid cells (CD4+ T cells; αβ and γδ T cells; CD20+ B cells). Results are expressed as medians and 5% confidence intervals.

Results: In fibrovascular septae, a surge of CD33+ immigrants clearly correlating with disease activity generated significantly increased (p<0.05) percentages of CD14+ and RFD7+ macrophages. Intriguingly, CD4+ cells were mostly γδ T cells, while αβ T helper cells were much less frequent. Successful treatment rendering TAO inactive apparently downregulates monocyte influx, macrophage differentiation, and T cell receptor expression. Similar trends were recorded for adipose tissue. Interestingly, RFD1+ DCs were completely absent from all conditions examined.

Conclusion: A-TAO coincides with periorbital monocyte infiltration and de novo differentiation of macrophages, but not DCs. The authors discuss a novel potential role for inflammatory CD4+ γδ T cells in TAO. Successful treatment apparently downregulates orbital monocyte recruitment and effects functional T cell knockout.

Keywords: TAO, CD4, CD33, γδ T lymphocytes, Graves’ ophthalmopathy

Thyroid associated ophthalmopathy (TAO) correlates with Graves’ hyperthyroidism in about 80% of all cases. Its immunopathology is incompletely understood. However, activation of orbital fibroblasts by inflammatory mediators appears pivotal in the pathogenesis of TAO: activated fibroblasts release increased amounts of the glycosaminoglycan hyaluronan which accumulates intraorbitally. Because one of this molecule’s major properties is to bind water at about ×1000 its own weight, the orbital adipose tissue develops a dramatically increased need for space. Cytokine triggered differentiation of adipogenic fibroblasts expands the orbital fat compartment even further. 1 These processes, together with the altered cytokine milieu, cause intraorbital scar formation. The typical symptoms of TAO—periorbital swelling, proptosis, and impairment of motility—thus result from the activation, differentiation, and proliferation of fibroblasts, as well as scar formation. 2– 5 Studies on the inflammatory activation of orbital fibroblasts in TAO have shown an involvement of immune cell derived mediators and fibroblast surface gangliosides. 6– 8 Importantly, orbital fibroblasts also express the costimulatory transmembrane molecule CD40 9 which is normally absent from these cells. 10, 11 As CD40 interacts with the stimulating T helper (Th) cell molecule CD154, it has been hypothesised that orbital fibroblasts may be activated by Th cells. Yet the structure of CD40 implies further unidentified ligands, 10 so that the actual process currently remains elusive.

In TAO, leukocyte signals can activate orbital fibroblasts. Macrophages and T cells apparently play a dominant role. 12, 13 However, several important questions as to the origin and composition of these cells have not yet been addressed. Firstly, it is unknown which intraorbital compartment is specifically infiltrated: such knowledge may pave the way for improving therapeutic improvement. Secondly, it appears crucial to clarify a possible pathogenetic role of myeloid dendritic cells (DCs). These potent antigen presenting cells can differentiate from monocytes, 14– 16 and, intriguingly, RFD1+ DCs play a prominent role in Graves’ disease. 17 Thus, DCs might qualify as a link between immunopathogenetic processes in thyroid and orbit. A third, more controversial issue refers to the intraorbital T lymphocytes. In early stage TAO, most of these cells express CD4 and secrete an αβ Th1 type cytokine profile. 13, 18– 23 Moreover, engagement of CD40 on orbital fibroblasts triggers hyaluronan synthesis and activation of inflammatory cyclooxygenases. 1, 9 These findings seem to indicate a dominant role of CD4+/CD154+ αβ Th1 cells in TAO. However, in some inflammatory diseases, CD4+ γδ T cells exert likewise effects 24– 26 (in healthy people, most γδ T cells are CD4 negative 27, 28 ), thus suggesting a potential involvement of such cells in TAO.

We have therefore examined intraorbital tissue for site specific leukocyte infiltration and local differentiation of macrophages and DCs, and we caution against the concept that the presence of CD4+ T cells secreting a suggestive cytokine pattern per se verifies an αβ Th cell status.

METHODS

Patients

This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the University of Essen. Periocular tissue obtained from age and sex matched patients was immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and assigned to the groups given below.

Active TAO

Patients with A-TAO (NOSPECS classification I–VI, that is, with optic nerve compression) required orbital bony decompression (n = 15; table 1 ). Mean duration of thyroid disease was 2.2 (SD 2.3) years, with 1.3 (SD 1.3) years for TAO. Before surgery, all patients had received ⩾1 cycles of steroid treatment, and all but three had received orbital irradiation (12–16 Gy). However, these therapeutic measures failed to reduce the clinical activity score which, at time of surgery, was 9.4 (SD 1.0).

Table 1.

TAO patient characteristics. Results shown as mean (SD)

| Symptoms | A-TAO (n = 15) | I-TAO (n = 11) |

| Thyroid disease (years) | 2.2 (2.3) | 3.6 (1.7) |

| TAO (years) | 1.3 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.9) |

| Steroid treatment | All | All |

| Months after steroid treatment | 5.2 (3.6) | 28.4 (23.0) |

| Orbital irradiation (Gy) | 12 | 8 |

| Months after irradiation | 6.5 (2.6) | 19.8 (13.0) |

| Clinical activity score | 9.4 (1.0) | 0.8 (0.7) |

| Proptosis (mm) | 22.8 (3.2) | 17.1 (4.3) |

Inactive TAO

Patients with I-TAO (NOSPECS III–V) underwent either orbital bony decompression to reduce proptosis or fat resection (n = 11; table 1 ). Mean duration of thyroid disease was 3.6 (SD 1.7) years, and 3.1 (SD 1.9) years for TAO. Steroid treatment, irradiation, and outcomes were identical to those specified for group 1. Upon surgery the mean clinical activity was 0.8 (SD 0.7).

Controls

Control tissue (n = 12) was obtained upon surgery for ptosis, or lateral orbitotomia for resection of a benign tumour.

Immunohistochemistry

The method has been described before. 17 Briefly, 5 μm cryostat sections were fixated in acetone, blocked against Fc receptor dependent antibody binding, stained with primary mouse antihuman monoclonal antibodies (table 2 ), and incubated for 20 min with streptavidin (1:500) and either EnVision+ peroxidase (for biotinylated anti-CD33) or secondary rabbit antimouse immunoglobulin (for all other markers) (Dako, Hamburg, Germany). Labelled antigens were visualised with 3-amino-9-ethyl-carbazole (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA); the chromogen was always freshly prepared (see reference 17). Sections were sequentially incubated in 4% formalin and 1% 1:10 acetic acid, and counterstained with Gill’s haematoxylin No 3 (Sigma). Isotype controls for IgG1 (W3/25), IgG2a (OX34), and IgG2b (TEN-0) (Serotec, Oxford, UK) were negative in all of the cases.

Table 2.

Monoclonal antibodies and their characteristics

| Antigen(s) | Clone(s)* | Isotype† | Cellular reactivity |

| CD4 | 1F6 | IgG1 | Mostly T helper cells |

| CD8 | 4B11 | IgG2b | Cytotoxic and T suppressor cells |

| CD14 | UCHM1 | IgG2a | Monocytes; early tissue macrophage |

| CD20 | 7D1 | IgG1 | B lymphocytes |

| CD33 | WM54 | IgG1 | Recently infiltrated blood monocytes |

| CD45 | 2B11+ PD7/26‡ | IgG1 | All leukocytes |

| T cell receptors αβ§ | 8A3 | IgG1 | All T cells expressing αβ T cell receptors |

| T cell receptors γδ¶ | γ 3.20 | IgG1 | All T cells expressing γδ T cell receptors |

| HLA-DR, DP, DQ, DX | CR3/43 | IgG1 | MHC class II expressed by professional and facultative antigen presenting cells |

| RFD1 antigen | RFD1 | IgM | Dendritic cells |

| RFD7 antigen | RFD7 | IgG1 | Mature and inflammatory macrophages |

*Sources: DAKO, Hamburg, Germany (CR3/43); Serotec, Oxford, UK (all others).

†Mouse antihuman antibodies throughout.

‡Antibodies recognise the CD45 and CD45RB splicing variants.

§Antibody recognises a common αβ chain framework determinant.

¶Antibody recognises a monomorphic epitope present on all TCR Cγ domains.

Statistical analysis

Tissue areas were evaluated separately. For each antigen, three random tissue areas per specimen were counted independently by two investigators. Medians and 5% confidence intervals were calculated from the arithmetic means. Using SPSS software, p<0.05 (control v disease) obtained with the Mann-Whitney U-Wilcoxon rank sum W test was considered significant.

RESULTS

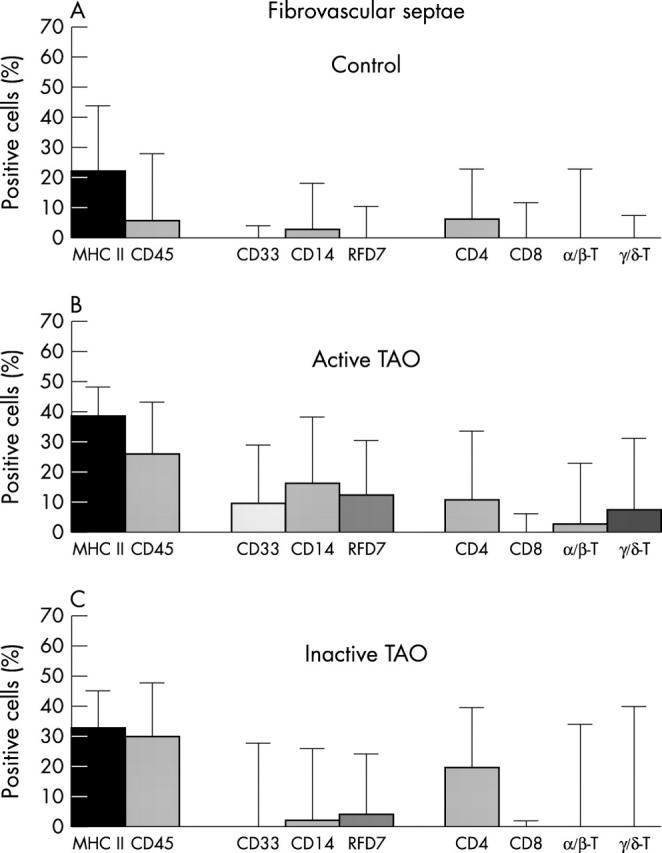

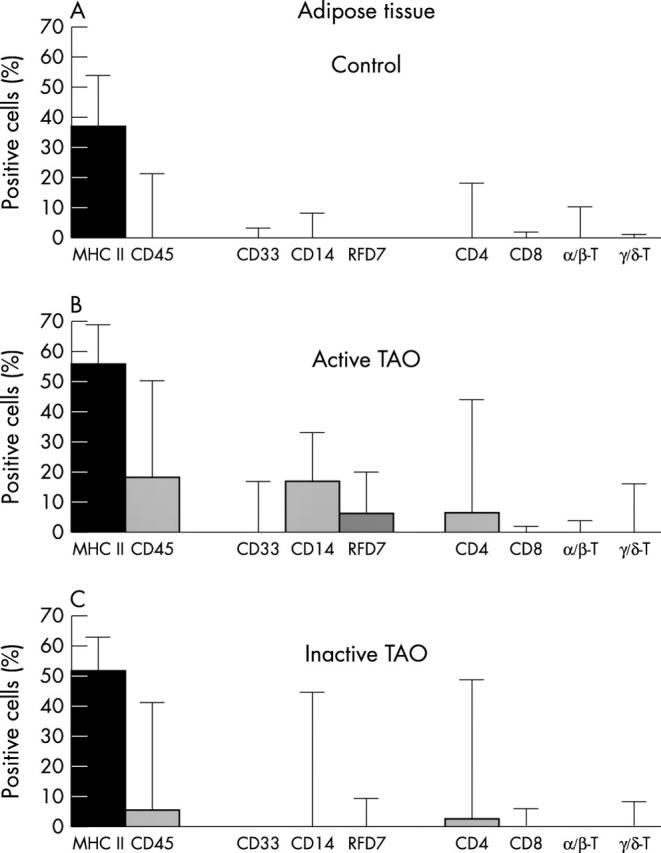

Fibrovascular septae harboured much higher percentages of stained leukocyte populations than adipose tissue. Compared with normal controls, TAO sections also revealed considerably increased total septal areas and thickness (compare figs 1A and 2A ). Comparison between A-TAO and I-TAO of a given antigen showed lower intraindividual, but higher interindividual, variation (figs 3 and 4 ).

Figure 1.

Representative immunohistochemistry of the leukocyte infiltrate in fibrovascular septae of a patient with active TAO after staining for (A) MHC class II; (B) CD14; (C) RFD7, and (D) CD33. Note the intense staining for MHC class II (covering HLA-DR, DP, DQ, and DX). Areas revealing faint expression suggest that these molecules are increasingly shed in active disease and attach to neighbouring structures. Also note the scattered monocyte and macrophage morphologies displaying CD33, CD14, and RFD7. Original magnification ×400.

Figure 2.

Fibrovascular septae in periocular control tissue (see legend to fig 1 ). Control tissue harboured almost none of the cells detected in A-TAO. Also note that the fibrovascular tissue is much less voluminous than in A-TAO. Original magnification ×400.

Figure 3.

Quantification of leukocytes in periorbital fibrovascular septae of (A) control subjects, (B) patients with active TAO, and (C) patients with inactive TAO. Specimens were stained for MHC class II molecules and leukocyte common antigen CD45 (first set of bars); myeloid marker CD33 indicating recently infiltrated monocytes, monocyte and early tissue macrophage marker CD14, and the RFD7 antigen expressed by mature and inflammatory macrophages (second set of bars); as well as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and the T cell receptor variants discriminating αβ and γδ T cells (third set of bars). Dendritic cells (RFD1) or B lymphocytes (CD20) were not detected and have, therefore, been omitted from the graphs. Note that the increase in numbers of cells expressing CD33, CD14 and/or RFD7 correlates significantly with disease activity. This increase is paralleled by a higher percentage of MHC class II+ cells. Also note that decreased disease activity, most interestingly, is accompanied by an even higher number of CD4+ cells, yet a virtually complete loss of γδ and αβ T cell receptor expression. Data are given as medians with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 4.

Cells in periorbital adipose tissue of (A) controls, (B) patients with A-TAO, and (C) patients with I-TAO. For markers and statistics notes, see legend to figure 3 . Control adipose tissue revealed lower leukocyte numbers than control fibrovascular tissue. This is in line with a much less pronounced infiltration of adipose tissue by disease associated myeloid and lymphoid cell types. Nevertheless, TAO associated alterations were qualitatively similar to those observed in the fibrovascular septae, with the important exception of freshly invading CD33+ blood monocytes. Also note that, in stark contrast to fibrovascular tissue, decreased disease activity was accompanied by a concomitant decrease in CD4+ cells.

Leukocytes

Unaffected fibrovascular controls revealed only low numbers of CD45+/CD45RB+ leukocytes. In contrast, in A-TAO, leukocytes were elevated significantly (figs 3 and 4 ). However, clusters or clones of stained cells were virtually absent, thus contradicting a potential scenario of local stimulation of antigen specific immunity. Interestingly, in I-TAO, percentages of fibrovascular leukocytes were still slightly high whereas evidently reduced in adipose tissue.

MHC class II+ cells

Percentages of periocular cells expressing MHC II (see table 2 ) always exceeded those of total leukocytes. Such cells mostly displayed fibroblast or macrophage morphologies (figs 3 and 4 ). Even in normal orbital tissue, considerable numbers of cells expressed class II molecules. However, owing to invading monocytes and their macrophage derivatives, the amount of MHC II+ cells increased significantly in A-TAO. Moreover, these macrophages shed class II molecules, thereby indicating their activated state (fig 1 ).

In I-TAO, numbers of fibrovascular MHC II+ macrophages still remained higher than control values, which correlated with the numbers and localisation of residual CD14+ and RFD7+ macrophages (see below). In contrast, numbers of adiposally located macrophages had returned to normal, while MHC II expression was still highly elevated (fig 4 ). This latter finding indicates that increased numbers of adipocytes were activated to persistently express MHC II, and/or that previously shed class II was bound to and retained on their surface.

Myeloid cells

The increased numbers of myeloid cells in orbital tissue of patients with A-TAO (figs 3 and 4 ) comprised a considerable proportion of recently immigrated CD33+ blood monocytes. This correlated with increased numbers of cells revealing CD14, an LPS receptor expressed by both recent monocytes and disease associated macrophages (see Discussion). In addition, percentages of mature activated RFD7+ macrophages, most likely differentiated from earlier CD14+/CD33+ stages, were also increased. In fibrovascular septae, all these mononuclear cell types rose with statistical significance (p<0.05) compared with control tissue.

Conversely, comparison with A-TAO revealed an inverted trend for I-TAO. Although not all values returned to normal, fibrovascular CD14+ cells were found significantly reduced (fig 3 ), and adiposal RFD7+ macrophages even returned to control percentages (p<0.05) (fig 4 ). However, fibrovascularly located RFD7+ macrophages remained slightly above the control level. All these findings indicate that the influx of monocytes—as well as successive macrophage differentiation—cease as TAO becomes inactive.

Finally, RFD1+ dendritic cells were never detected in any patient or control sample. In contrast, thyroid sections of patients with Graves’ disease (the most suitable positive control) had always revealed many strongly RFD1+ DCs. 10

Lymphoid cells

In virtual absence of CD8+ cytotoxic/suppressor T cells and CD20+ B lymphocytes (not shown), CD4+ T cells were the predominant intraorbital lymphoid cell population (figs 3 and 4 ), thus confirming earlier results. 12, 13 We then inquired whether these cells carry αβ or γδ T cell receptors (TCRs). In healthy people, we found a minute predominance of αβ over γδ T cells (fig 3A and B ). However, in A-TAO, and most prominently in the fibrovascular septae, about 75% of the local T cells expressed γδ TCRs (fig 3B ). Moreover, total numbers and localisation of γδ and αβ T cells perfectly matched those of the CD4+ cells, thus clearly indicating that most CD4+ T cells were, indeed, TCR-γδ positive. Numbers of TCR-αβ+/CD4+ T helper cells were much lower. Actually, in active TAO, TCR-γδ+/CD4+ cells, on average, constituted for 27% of all CD45+ leukocytes within the orbit, whereas control tissue only revealed an occasional patrolling γδ T cell.

Another interesting finding was the almost complete loss of TCR expression in I-TAO, although CD4+ cells were still demonstrable. If only referring to adipose tissue, this conclusion could not be justified (fig 4C ), yet results obtained from the fibrovascular areas were unequivocal: despite the presence of even increased numbers of CD4+ T cells, they almost never expressed γδ or αβ TCRs in this stage of disease (fig 3C ). Conversely, in active disease, TCR+ cells always added up nicely to the numbers of CD4+ lymphocytes (fig 3B ).

Cell kinetics

As to the pathogenesis of TAO, it appears desirable to learn about the kinetics of myeloid and lymphoid cells in the course of disease. However, it should be cautioned that, even in the stage before disease, patients prone for TAO might reveal intraorbital leukocyte proportions differing from those in non-predisposed control subjects. Nevertheless, while bearing this in mind, we have aligned the respective graphs as a suggestive pathogenetic time line—that is, healthy controls (figs 3A and 4A ), A-TAO (figs 3B and 4B ), and I-TAO (figs 3C and 4C ). When generalising, this sequence may suggest the following intraorbital processes:

Numbers of myeloid cells increase considerably during the active phase of disease, but resume almost normal values in I-TAO.

Of note, in A-TAO, early CD33+ monocytes only surface within fibrovascular septae, thus indicating that they specifically infiltrate this compartment (compare figs 3B and 4B ), and that this is a characteristic of active disease progression (compare figs 3B and 3C ).

While downregulating CD33 shortly after colonising a solid tissue, monocytes retain CD14 for prolonged times. Comparable percentages of CD14+ cells in both tissue compartments illustrate that such cells cross migrate the entire intraocular space before settling.

However, most migrating monocytes eventually assume permanent residency within the septal areas, as evidenced by acquisition of the terminal tissue macrophage marker RFD7 (compare figs 3B and 4B ).

Some fibrovascular RFD7+ cells are still demonstrable in I-TAO (fig 3C ). Yet, because macrophages are long lived cells, it appears most likely that these are old, residual macrophages that are inert and, thus, no longer propagate the progression of disease.

The recorded T cell data suggest that these cells, too, enter the intraorbital space via the fibrovascular regions (figs 3B and 4B ).

Therefore, regardless of the cell type, infiltration of adipose tissue appears to be a secondary event.

DISCUSSION

Consistent presence of leukocytes in unaffected periocular fibrovascular tissue indicates continuous immunological surveillance of the orbital space. However, additional immune cells colonise the periocular tissues in A-TAO. We have characterised the types, stages, and kinetics of such cells.

According to our results, DCs are not implicated in the pathogenesis of TAO. RFD1+ DCs, therefore, apparently do not qualify as a pathogenetic link between orbit and eye, whereas such cells play a major role in Graves’ disease (see reference 17 and the references therein). This is in line with the lack of orbital leukocyte aggregates as indicators of DC mediated antigen specific immunity; just the opposite was shown in Graves’ thyroids. 17

Despite the lack of notable local proliferation, percentages of intraorbital leukocytes significantly increased in A-TAO. Confirming earlier results, 12, 13 these cells mainly comprised macrophages and CD4+ T cells. Their circulating precursors apparently access fibrovascular septae via vascular adhesion molecules that are upregulated in TAO. 29– 31

Loss of T cell receptor expression

Intriguingly, in I-TAO virtually all intraorbital T cells had downregulated TCR expression. It is known that antigen/TCR engagement downregulates TCR expression; 32 TCRs are also downmodulated by viral proteins such as HIV-2/SIV Nef or Herpesvirus saimiri Tip. 33– 35 However, one should expect greater interindividual differences if these paradigms were to apply. In contrast, all patients assigned to the I-TAO group had received steroid treatment. Migliatori et al had earlier shown downregulation of the TCR/CD3 complex by such treatment, 36 and Galon et al 37 recently demonstrated that glucocorticoids potently downregulate TCR-αβ and TCR-γδ. We thus interpret the TCR loss in TAO to be a direct consequence of steroid treatment.

De novo differentiation of orbital macrophages

Increase in intraorbital macrophages in A-TAO results from continuous monocyte influx, as evidenced by their expression of CD33. Successively, these immigrants express CD14 and RFD7. These markers indicate pathogenetic relevance: CD14 upregulated macrophages have been shown in extrinsic allergic alveolitis, 38 pulmonary sarcoidosis, 39 and inflammatory bowel disease. 40 Expression of CD14 is suppressed by Th2 like, 41, 42 but induced by Th1 like, 43 cytokines, such as are secreted in TAO. 19– 23 Furthermore, RFD1+/RFD7+ expression characterises mature activated tissue macrophages. 44, 45 However, a RFD1−/RFD7+ phenotype—as in TAO—clearly denotes inducer macrophages 46 characteristic of chronic inflammatory lesions. 47 The presence of such cells in TAO and their strong correlation with disease activity thus match the high local concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines. 3, 22, 29, 30 These phenotypic results suggest local sequential macrophage differentiation, according to CD33+ → CD14+ → RFD7+. The finding that such macrophages are recruited from freshly infiltrated monocytes, but not local resident macrophages, might lead to new treatment options.

Inflammatory CD4+ γδ T cells

Previous investigation led to the notion that Th1 cells dominate in early TAO, whereas Th2 cells may be more characteristic of late stage disease. 19, 23, 48 Consequently, Th1 cells are thought to play a prominent role in A-TAO. Our results now challenge this interpretation of earlier results: on average, 75% of all intraorbital CD4+ cells express TCR-γδ. Pathogenetically, γδ T cells thus appear much more compelling than the smaller αβ T cell subset.

In healthy people, CD4− γδ T cells preferentially populate surface forming tissues. 27, 28 However, CD4+ γδ T cells secreting “Th1 like” cytokines have been shown in chronically inflamed sites of gut, gingiva, synovia, and after parasitic infection. 24– 26, 49 Increased numbers of γδ T cells have also been reported in autoimmunity (for example, coeliac disease, multiple sclerosis/experimental allergic encephalomyelitis, and rheumatoid arthritis), as well as intestinal wheat allergy. 28

Evidence supports two main functions of γδ T cells: (1) protection against superantigens and intracellular infection and (2) induction of tolerance for harmless nutritional and bacterial compounds encountered at mucosal surfaces. 27 However, as an example, certain bacterial heat shock proteins are highly homologous to self antigens upregulated in stress. 27, 49, 50 By crossreacting with such autoantigens, γδ T cells might thus be triggered to propagate inflammation or autoimmunity. 27, 49, 50

γδ T cells have been discovered to regulate autoimmune responses. 50 Their identification in TAO may thus open an exciting new chapter in unravelling the pathogenesis of TAO and its association with Graves’ hyperthyroidism. The case that γδ T cells present unprocessed proteins (including superantigens), and “exotic” compounds such as pyrophosphomonoester, alkylamine, and aminobisphosphonate, 27, 28, 50, 51 might provide clues to their pathogenetic function in TAO.

Acknowledgments

All authors would like to thank BRAHMS Diagnostica GmbH, Hennigsdorf, Germany, for kindly supporting part of this study. RKG is grateful to Michael J Hahn, BA (LTBH Medical Research Institute), for critically reading the manuscript.

Abbreviations

DC, dendritic cell

TAO, thyroid associated ophthalmopathy

TCR, T cell receptor

Th, T helper

REFERENCES

- 1. Kazim M, Goldberg RA, Smith TJ. Insights into the pathogenesis of thyroid-associated orbitopathy: evolving rationale for therapy. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:380–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wiersinga WM, Smit T, van der Gaag R, et al. Clinical presentation of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Ophthalmic Res 1989;21:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bahn RS, Heufelder AE. Pathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1468–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartley GB, Fatourechi V, Kadrmas EF, et al. Clinical features of Graves’ ophthalmopathy in an incidence cohort. Am J Ophthalmol 1996;121:284–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perros P, Kendall-Taylor P. Thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy: pathogenesis and clinical management. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995;9:115–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smith TJ, Sempowski GD, Wang HS, et al. Evidence for cellular heterogeneity in primary cultures of human orbital fibroblasts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995;80:2620–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith TJ, Sempowski GD, Berenson CS, et al. Human thyroid fibroblasts exhibit a distinctive phenotype in culture: characteristic ganglioside profile and functional CD40 expression. Endocrinology 1997;138:5576–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sempowski GD, Rozenblit J, Smith TJ, et al. Human orbital fibroblasts are activated through CD40 to induce proinflammatory cytokine production. Am J Physiol 1998;274:C707–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cao HJ, Wang HS, Zhang Y, et al. Activation of human orbital fibroblasts through CD40 engagement results in a dramatic induction of hyaluronan synthesis and prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase-2 expression. Insights into potential pathogenic mechanisms of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. J Biol Chem 1998;273:29615–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gordon J, Challa A, Pound J, et al. Protein reviews on the web: the guide on CD40. Last updated: 1 December 1999. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/prow/guide/551041808_g.htm.

- 11. HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) Gene Family Nomenclature: The new TNF nomenclature scheme. Last updated: May 2002. http://www.gene.ucl.ac.uk/nomenclature/genefamily/tnftop.html.

- 12. Kahaly G, Hansen C, Felke B, et al. Immunohistochemical staining of retrobulbar adipose tissue in Graves’ opthalmopathy. Cin Immunol Immunopathol 1994;73:53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pappa A, Lawson JM, Calder V, et al. T cells and fibroblasts in affected extraocular muscles in early and late thyroid associated ophthalmopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2000;84:517–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gieseler RK, Röber R-A, Kuhn R, et al. Dendritic accessory cells derived from rat bone marrow precursors under chemically defined conditions in vitro belong to the myeloid lineage. Eur J Cell Biol 1991;54:171–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gieseler RK, Xu H, Schlemminger R, et al. Serum-free differentiation of rat and human dendritic cells, accompanied by acquisition of the nuclear lamins A/C as differentiation markers. Adv Exp Med Biol 1993;329:287–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gieseler R, Heise D, Soruri A, et al. In-vitro differentiation of mature dendritic cells from human blood monocytes. Dev Immunol 1998;6:25–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Quadbeck B, Eckstein AK, Tews S, et al. Maturation of thyroidal dendritic cells in Graves’ disease. Scand J Immunol 2002;55:612–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stover C, Otto E, Beyer J, et al. Cellular immunity and retrobulbar fibroblasts in Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Thyroid 1994;4:161–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang D, Hiromatsu Y, Hoshino T, et al. Dominant infiltration of TH1-type CD4+ T cells at the retrobulbar space of patients with thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Thyroid 1999;9:305–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Carli M, D’Elios MM, Mariotti S, et al. Cytolytic T cells with Th1-like cytokine profile predominate in retroorbital lymphocytic infiltrates of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1993;77:1120–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McLachlan SM, Prummel MF, Rapoport B. Cell-mediated or humoral immunity in Graves’ ophthalmopathy? Profiles of T-cell cytokines amplified by polymerase chain reaction from orbital tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994;78:1070–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pappa A, Calder V, Ajjan R, et al. Analysis of extraocular muscle-infiltrating T cells in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy (TAO). Clin Exp Immunol 1997;109:362–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aniszewski JP, Valyasevi RW, Bahn RS. Relationship between disease duration and predominant orbital T cell subset in Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:776–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Söderström K, Bucht A, Halapi E, et al. High expression of Vγ8 is a shared feature of human γδ T cells in the epithelium of the gut and in the inflamed synovial tissue. J Immunol 1994;152:6017–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lundqvist C, Baranov V, Teglund S, et al. Cytokine profile and ultrastructure of intraepithelial γδ T cells in chronically inflamed human gingiva suggest a cytotoxic effector function. J Immunol 1994;153:2302–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goodier MR, Lundqvist C, Hammarström ML, et al. Cytokine profiles for human Vγ9+ T cells stimulated by Plasmodium falciparum. Parasite Immunol 1995;17:413–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gieseler R. γδ-T cells and the mucosa associated lymphoid tissue. A hypothesis on the immunologic function of γδ T cells. Int Z Biomed Forsch Ther 1996;25:204–10. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hayday A, Tigelaar R. Regulatory lymphocytes: immunoregulation in the tissues by γδ T cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2003;3:233–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heufelder AE, Bahn RS. Elevated expression in situ of selectin and immunoglobulin superfamily type adhesion molecules in retroocular connective tissues from patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Clin Exp Immunol 1993;91:381–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pappa A, Calder V, Fells P, et al. Adhesion molecule expression in vivo on extraocular muscles (EOM) in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy (TAO). Clin Exp Immunol 1997;108:309–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Heufelder AE, Bahn RS. Graves’ immunoglobulins and cytokines stimulate the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in cultured Graves’ orbital fibroblasts. Eur J Clin Invest 1992;22:529–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Carrasco YR, Navarro MN, Toribio ML. A role for the cytoplasmic tail of the pre-T cell receptor (TCR) alpha chain in promoting constitutive internalization and degradation of the pre-TCR. J Biol Chem 2003;278:14507–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Münch J, Janardhan A, Stolte N, et al. T-cell receptor:CD3 down-regulation is a selected in vivo function of simian immunodeficiency virus Nef but is not sufficient for effective viral replication in rhesus macaques. J Virol 2002;76:12360–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schaefer TM, Bell I, Pfeifer ME, et al. The conserved process of TCR/CD3 complex down-modulation by SIV Nef is mediated by the central core, not endocytic motifs. Virology 2002;302:106–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Park J, Lee BS, Choi JK, et al. Herpesviral protein targets a cellular WD repeat endosomal protein to downregulate T lymphocyte receptor expression. Immunity 2002;17:221–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Migliorati G, Bartoli A, Nocentini G, et al. Effect of dexamethasone on T-cell receptor/CD3 expression. Mol Cell Biochem 1997;167:135–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Galon J, Franchimont D, Hiroi N, et al. Gene profiling reveals unknown enhancing and suppressive actions of glucocorticoids on immune cells. FASEBJ 2002;16:61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pforte A, Schiessler A, Gais P, et al. Increased expression of the monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 in extrinsic allergic alveolitis. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 1993;48:607–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pforte A, Schiessler A, Gais P, et al. Expression of CD14 correlates with lung function impairment in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Chest 1994;105:349–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grimm MC, Pavli P, van de Pol E, et al. Evidence for a CD14+ population of monocytes in inflammatory bowel disease mucosa—implications for pathogenesis. Clin Exp Immunol 1995;100:291–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ruppert J, Schütt C, Ostermeier D, et al. Down-regulation and release of CD14 on human monocytes by IL-4 depends on the presence of serum or GM-CSF. Adv Exp Med Biol 1993;329:281–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lauener RP, Goyert SM, Geha RS, et al. Interleukin 4 down-regulates the expression of CD14 in normal human monocytes. Eur J Immunol 1990;20:2375–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Matsuura K, Ishida T, Setoguchi M, et al. Upregulation of mouse CD14 expression in Kupffer cells by lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med 1994;179:1671–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Poulter LW, Campbell DA, Munro C, et al. Discrimination of human macrophages and dendritic cells by means of monoclonal antibodies. Scand J Immunol 1986;24:351–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tormey VJ, Bernard S, Ivory K, et al. Fluticasone propionate-induced regulation of the balance within macrophage subpopulations. Clin Exp Immunol 2000;119:4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Spiteri MA, Poulter LW. Characterization of immune inducer and suppressor macrophages from the normal human lung. Clin Exp Immunol 1991;83:152–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Allison MC, Poulter LW. Changes in phenotypically distinct mucosal macrophage populations may be a prerequisite for the development of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Immunol 1991;85:504–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Natt N, Bahn RS. Cytokines in the evolution of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Autoimmunity 1997;26:129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cardona AE, Teale JM. γ/δ T cell-deficient mice exhibit reduced disease severity and decreased inflammatory response in the brain in murine neurocysticercosis. J Immunol 2002;169:3163–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hayday A, Geng L. γδ cells regulate autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol 1997;9:884–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Allison TJ, Garboczi DN. Structure of γδ T cell receptors and their recognition of non-peptide antigens. Mol Immunol 2002;38:1051–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]