Abstract

Aims: To determine the indications for penetrating keratoplasty (PK) at the Corneoplastic Unit and Eye Bank, UK, a tertiary referral centre, over a 10 year period.

Methods: Records of all patients who underwent PK at our institution between 1990 and 1999 were reviewed retrospectively. Of the 1096 procedures performed in this period, 784 records were available for evaluation (72%).

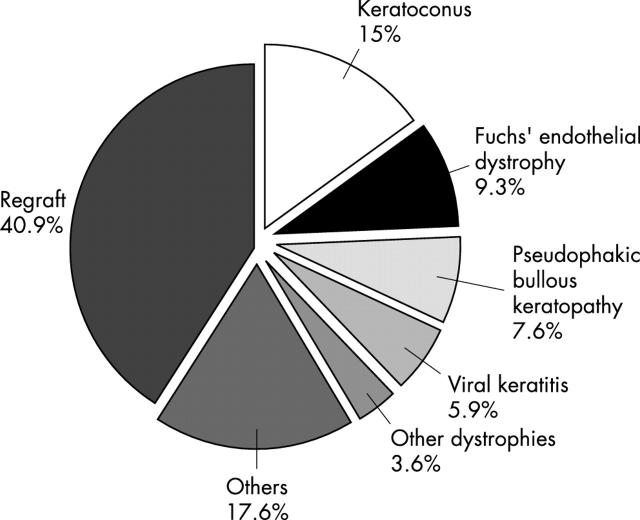

Results: Regrafting was the most common indication, accounting for 40.9% of all cases. Keratoconus was the second most common indication (15%), followed by Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy (9.3%), pseudophakic bullous keratopathy (7.6%), and viral keratitis (5.9%), which included both herpes simplex and herpes zoster and showed a statistically significant decreasing trend using regression analysis (p<0.005). Among the regraft subgroup, viral keratitis accounted for 21.2% as the underlying primary diagnosis. The most common cause for graft failure in the regraft subgroup was endothelial failure (41.8%).

Conclusion: Regrafting is the leading indication for PK; viral disease—although declining—is the leading primary diagnosis.

Keywords: cornea, indications, keratoplasty, herpes

Penetrating keratoplasty (PK) is the most common tissue transplant performed in Europe and the United States. Advances in the medical management of certain diagnoses and the adoption of a conservative approach have changed patterns in the indications of PK. Moreover, the decline of certain disorders due to changes in surgical practice, and the emergence of new surgical techniques have largely influenced the changing trend. The indications for PK have continued to change since 1940,1–3 and investigators have studied the changing trends over the past few decades.1–19 To update these trends we report the indications for PK from 1990 to 1999, and compare these with indications during an earlier time period at the same institution4 and to those of other series.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A retrospective analysis of records of all cases of PK performed between January 1990 and December 1999 was undertaken. All cases were performed at the Corneoplastic Unit and Eye Bank, UK, a tertiary referral centre for corneal and anterior segment disorders. Of the 1097 PKs performed in this period, only 784 medical records were available for review. Records were not accessible or had been destroyed as patients had not been followed up—either because they lived abroad, transferred to another institution, or had died. Although the indications for PK for the remaining 313 cases could be retrieved from the booking register, we elected not to include these as there was little correlation between the data recorded in the operative note and the register. Information obtained was analysed with respect to age, sex, eye grafted, and preoperative clinical diagnosis. The indications for PK were divided into seven diagnostic categories (fig 1). Regrafts were further analysed for the aetiology of failure of the previous graft and original diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Indications for penetrating keratoplasty (PK), 1990–1999. Regraft (n = 321, 40.9%) was the most common indication for PK. Keratoconus was the second most common diagnosis (n = 118, 15%), followed by Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy (n = 73, 9.3%), pseudophakic bullous keratopathy (n = 60, 7.6%), viral keratitis (n = 46, 5.9%), and other dystrophies (n = 28, 3.6%). These six indications account for 82.3% of indications for PK. Aphakic bullous keratopathy, injuries, interstitial keratitis, and ulcerative keratitis accounted for most of the remaining cases (n = 138, 17.6%).

Statistical significance was determined using χ2 analysis. A combination of linear regression and t test were used to establish linear trends and to determine the statistical significance of the trend.

RESULTS

Of the 784 cases performed, 714 (91%) had the graft performed for visual reasons. Sixty five (8.3%) were for therapeutic reasons such as unresponsive infection (n = 13, 1.7%), threatened perforation (n = 9, 1.1%), and actual perforation (n = 43, 5.5%). Only five cases (0.6%) were performed for cosmetic reasons. Of 13 eyes which had a PK for infection, seven cases were bacterial, one Acanthamoeba, and in the five remaining cases the infectious agent was unknown.

The mean patient age was 54.21 years with a standard deviation (SD) of 21.46 and a median of 56.5 years. The mean ages for the main diagnoses were regrafts 54.4 (SD 19.66) years, keratoconus 32.5 (SD 11.70) years, herpes infection 55.5 (SD 20.87) years, Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy 70 (SD 10.37) years, and pseudophakic bullous keratopathy (PBK) 75 (SD 9.74) years.

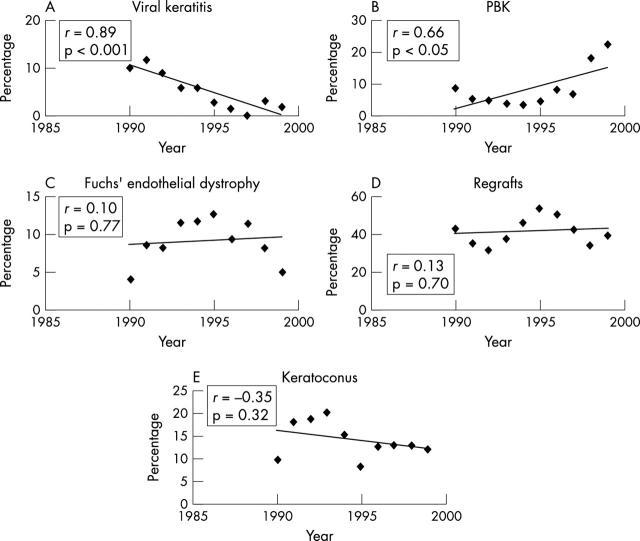

Overall, sex distribution showed slight male predominance with 54.7% males and 45.3% females. Using χ2 analysis for sex differences by diagnostic categories there was a statistically significant predominance among males with keratoconus (79 males, 39 females; p<0.001). No significant sex difference was found for the other diagnostic categories. The trends of the main indications for PK are illustrated in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Trends of the leading indications for penetrating keratoplasty (PK). Viral keratitis, which included both herpes simplex and herpes zoster, as an indication for PK, showed a statistically significant decreasing trend using regression analysis (A, p<0.001). Pseudophakic bullous keratopathy (PBK) increased, reaching a peak in 1999 (B, p<0.05). Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy, regrafts, and keratoconus fluctuated over this 10 year period and did not show a statistically significant trend (C–E). The correlation coefficient r measures the closeness of fit of the data to the regression line.

The underlying primary diagnosis and the reason for graft failure in the regraft subgroup were evaluated (table 1). Surgical procedures associated with PK are illustrated in table 2.

Table 1.

Analysis of regrafts: original diagnosis and cause of failure

| Original diagnosis | Causes of failure | ||

| Viral keratitis | 68 (21.2%) | Endothelial failure* | 134 (41.8%) |

| Dystrophies | 49 (15.2%) | Endothelial rejection† | 53 (16.5%) |

| Bullous keratopathy | 47 (14.6%) | Astigmatism | 20 (6.2%) |

| Trauma | 44 (13.7%) | Recurrence of dystrophy | 15 (4.7%) |

| Keratoconus | 41 (12.8%) | Perforation | 15 (4.7%) |

| Ulcerative keratitis | 10 (3.1%) | Bacterial infection | 13 (4%) |

| Corneal opacities | 10 (3.1%) | Scarring | 12 (3.7%) |

| Others | 40 (12.5%) | Primary donor failure | 7 (2.2%) |

| Unknown | 12 (3.7%) | Recurrent HSV keratitis | 7 (2.2%) |

| Impending perforation | 6 (1.9%) | ||

| Bacterial infection with perforation | 5 (1.5%) | ||

| Glaucoma | 5 (1.5%) | ||

| Trauma | 3 (0.9%) | ||

| Others | 14 (4.4%) | ||

| Unknown | 12 (3.7%) | ||

| Total | 321 (100%) | Total | 321 (100%) |

*Endothelial failure unrelated to endothelial rejection.

†Endothelial rejection leading to endothelial failure.

HSV, herpes simplex virus.

Table 2.

Surgical procedures associated with penetrating keratoplasty. All cases that had an anterior chamber lens implanted, underwent surgery from 1990–93

| PK+ECCE+IOL | Secondary IOL (aphakic) | IOL exchange primary implant | At exchange | |

| ACIOL | 5 (3.4%) | 8 (12%) | 35 (67.3%) | 12 (23%) |

| PCIOL | 140 (94.6%) | 10 (15%) | 2 (3.8%) | 6 (11.5%) |

| Transsclerally sutured IOL | 3 (2%) | 48 (73%) | 1 (1.9%) | 34 (65.5%) |

| Iris fixated IOL | 0 | 0 | 8 (15.4%) | 0 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 6 (11.5%) | 0 |

| Total | 148 | 66 | 52 | 52 |

PK, penetrating keratoplasty; ECCE, extracapsular cataract extraction; IOL, intraocular lens implant; ACIOL, anterior chamber IOL; PCIOL, posterior chamber IOL.

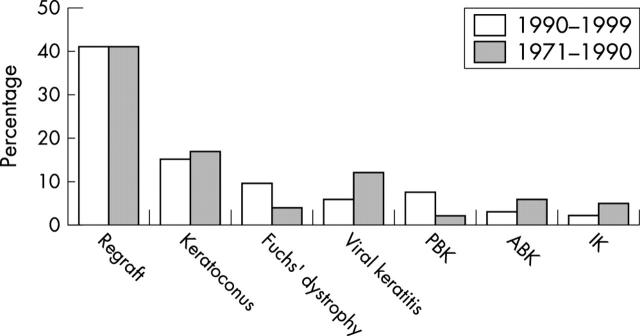

Figure 3 illustrates the comparison of the current indications for PK with those studied in the previous two decades.4

Figure 3.

Comparison of distribution of indications for penetrating keratoplasty at the Corneoplastic Unit and Eye Bank between 1990–99 and 1971–90. Regrafting was the most common indication in both series (40.9% and 40.8%, respectively). Keratoconus was the second most common indication and similar in both series (15% and 16.8%, respectively). Viral keratitis, which comprised 11.7% of the previous series, had a statistically significant decrease to 5.9% (p<0.005) in the present series. The frequency of both aphakic bullous keratopathy and interstitial keratitis were significantly higher in the previous series (p<0.005). Both pseudophakic bullous keratopathy and Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy had a statistically significant increase in the present series (p<0.005).

DISCUSSION

The Corneoplastic Unit and Eye Bank is a tertiary referral centre that deals primarily with corneal and anterior segment disorders. The indications for PK are not representative of those nationwide and clearly reflect the specialty nature of the institution (table 3). The category “other” in the table provided by UK Transplant accounted for 28% of indications. This is erroneous and reflects the operating surgeons’ unwillingness to categorise indications according to the list provided in the Transplant Record Form.

Table 3.

Comparison of indications for penetrating keratoplasty nationally (yearly intervals)* and at the Corneoplastic Unit and Eye Bank (CUEB), 1990–99

| Primary disease nationally (%) | Primary disease at CUEB, 1990–99 (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | Total | Total | ||

| Regraft† | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.36 | 40.9 | Regraft† |

| Keratoconus | 19 | 20 | 20 | 23 | 26 | 24 | 27 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 23.5 | 15 | Keratoconus |

| Fuchs’ dystrophy | 8 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 10.8 | 9.3 | Fuchs’ dystrophy |

| Endothelial failure: pseudophakic bullous keratopathy | 7 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 | – | 7.6 | 7.6 | Pseudophakic bullous keratopathy |

| Endothelial failure: aphakic bullous keratopathy | 13 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | – | 4.2 | ||

| Endothelial failure: other | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | – | 2.5 | ||

| Chronic inflammation: viral keratitis | 6 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | – | 3.5 | 5.9 | Viral keratitis |

| Chronic inflammation: other | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3.2 | |||

| Aetiology uncertain | 3 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | – | 4 | ||

| Trauma: mechanical | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | 1.3 | ||

| Other | 17 | 14 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 37 | 40 | 39 | 42 | 57 | 28 | 17.6 | Other |

| Ocular disease unknown | 13 | 22 | 29 | 30 | 27 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 13.4 | ||

| 3.6 | Other dystrophies | ||||||||||||

* National data provided by UK Transplant.

†Includes endothelial failure, rejection, primary failure, and other causes of failure.

Regrafting accounted for 40.9% of all PKs over 10 years, a figure that has essentially not changed from the last series spanning two decades (40.8%).4 It was also one of the leading indications at a number of institutions in Europe and North America.2,3,5–8,20,21 Regrafting can be expected to remain a leading indication for PK with the expanding pool of PK recipients and endothelial failure as a leading cause of graft failure. However with the growing interest in lamellar techniques, both deep and automated, the number of regrafts may in time decrease.

Viral keratitis comprising both herpes simplex and herpes zoster was the most common primary diagnosis in regrafts in our series, accounting for 21.2% of cases. The majority of these had a PK performed at another institution. Prophylactic antiviral treatment following PK has been used as standard practice at this institution since 1994. Acyclovir has been shown to significantly improve graft survival, and more common use of this modality may decrease the number of failed grafts from herpes simplex in the future.22–24 Viral keratitis was also the most common primary diagnosis in regrafts in previous reports from the UK, constituting 22–27%.5,25 Additionally, this study shows a statistically significant decline in viral keratitis as an indication for primary PK. This is consistent with national UK data (table 3) and probably reflects better medical management of Herpetic keratitis through use of topical and systemic antivirals, increased appreciation of the higher risk of graft failure in this disease and a consequent reluctance to perform PK. Viral keratitis accounted only for 2.3% in the Doheny Eye Institute and also demonstrated a decreasing trend compared with earlier reports from the same institution.8 Brady et al also showed viral disease declining progressively.12 This decline, along with the use of systemic acyclovir, may in time reduce viral keratitis as a primary diagnosis for regrafts.

The most common cause for graft failure in regrafts was endothelial failure (41.8%) followed by endothelial rejection (16.5%). Primary failure accounted for 2.2% of regrafts. Sharif et al4 (1971–1990) reported a rate of 4.5% and Moorfields Eye Hospital (1985–1987) 5.8%.5 This decrease in primary failure as a cause, reflects the improvement in eye banking over the last decade. Endothelial decompensation was also described at Moorfields Eye Hospital as the leading cause for graft failure.5 MacEwen et al,25 in their study of regrafts, similarly demonstrated that allograft rejection and endothelial failure accounted for most graft failure causes.

Although keratoconus is the leading indication for PK nationally (23.5%) (table 3), it was the second most common indication in this series (15%) as it was previously between 1975 and 1990 (16.8%).4 Keratoconus was more common in males in our series and similar preponderance has been reported previously,20,26 although female predominance has also been described.27,28 Keratoconus has and continues to be a leading indication for PK elsewhere1,3,5,9,21,29,30; however, with the resurgence of interest in lamellar techniques31–34 as well as the introduction of intracorneal rings,35 this may decrease in time.

Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy was the third most common indication at 9.3%. The reported rates of Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy are highly variable3,8,10–12,36,37 and probably due to different demographic pools and referral patterns. Although Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy is known to be more common among females,20,37,38 our study showed no statistically significant sex difference.

Although bullous keratopathy (aphakic and pseudophakic) has significantly declined nationally from 20% in 1990 to 9% in 1998 (table 3), this has not changed significantly as an indication for PK at our institution. However, as expected with increased use of intraocular lenses in cataract surgery in the mid 1980s, aphakic bullous keratopathy declined and PBK increased in our series (fig 3).

The incidence of PBK in the UK has been markedly lower than North America. Sharif et al4 reported 2% between 1975 and 1990. Between 1990 and 1999, PBK accounted for 7.6% in the UK (table 3) and the figure was identical in our series. In North America PBK became a leading indicator for PK in some series (Wills Eye Hospital 22.9%,12 Doheny Eye Institute 24.8%8) and was a result of the initial enthusiasm for lens implantation in cataract surgery, particularly with anterior chamber closed loop implants and iris clip lenses. The UK, in its highly conservative approach and slower acceptance of intraocular lenses, avoided this epidemic. Interestingly, although the national rate of PBK remained the same over the 10 year period (table 3), at our institution the rate of PBK increased (fig 2B)—possibly reflecting an increase in referral of postcataract extraction complications requiring anterior segment reconstruction.

With changes in medical and surgical management, one expects a change in indications for corneal transplantation, and indeed this has been reflected nationally in the UK. However it is interesting to note that the overall indications for PK at a referral centre have not essentially changed over a period of 30 years. Regrafts have continued to be a leading indication at an identical rate in two series at the same institution with viral disease, which although declining, being the lead primary diagnosis. Through further improvements in medical management and the advent of better surgical techniques for lamellar grafting and newer techniques of posterior lamellar and endothelial transplantation, the indications for PK and the role of a referral corneal institution may well change over the next 30 years.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Andrea Rowe, Eye Bank Coordinator, Dot Helme and Caroline Langridge, Department of Clinical Audit and Research, Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead, and Phil Pocock, Senior Biostatistician, UK Transplant.

Abbreviations

HSV, herpes simplex virus

PBK, pseudophakic bullous keratopathy

PK, penetrating keratoplasty

Presented in part at “CORNEA 2002 - celebrating 50 years of Eye Banking”, Gatwick, UK, 14 November 2002.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith RE, McDonald HR, Nesburn AB, et al. Penetrating keratoplasty, Changing indications, 1947 to 1978. Arch Ophthalmol 1980;98:1226–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemp MA. Indications for penetrating keratoplasty. Med Ann DC 1972;41:346–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arentsen JJ, Morgan B, Green WR. Changing indications for keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol 1976;81:313–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharif KW, Casey TA. Changing indications for penetrating keratoplasty, 1971–1990. Eye 1993;7:485–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris RJ, Bates AK. Changing indications for keratoplasty. Eye 1989;3:455–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robin JB, Gindi JJ, Koh K, et al. An update of the indications for penetrating keratoplasty, 1979 through 1983. Arch Ophthalmol 1986;104:87–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohamadi P , McDonnell JM, Irvine JA, et al. Changing indications for penetrating keratoplasty, 1984–1988. Am J Ophthalmol 1989;107:550–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flowers CW, Chang KY, McLeod SD, et al. Changing indications for penetrating keratoplasty, 1989–1993. Cornea 1995;14:583–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damji KF, Rootman J, White VA, et al. Changing indications for penetrating keratoplasty in Vancouver, 1978–1987. Can J Ophthalmol 1990;25:243–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindquist TD, McGlothan JS, Rotkis WM, et al. Indications for penetrating keratoplasty: 1980–1988. Cornea 1991;10:210–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyman L , Wittpenn J, Yang C. Indications and techniques of penetrating keratoplasties, 1985–1988. Cornea 1992;11:573–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brady SE, Rapuano CJ, Arentsen JJ, et al. Clinical indications for and procedures associated with penetrating keratoplasty, 1983–1988. Am J Ophthalmology 1989;108:118–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandler JW. Indications for penetrating keratoplasty and management of cases. Trans Pacific Coast Oto-ophthalmol Soc 1976;57:97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson CH. Indications, complications and prognosis for repeat penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmic Surg 1979;10:27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramsay AS, Lee WR, Mohammed A. Changing indications for penetrating keratoplasty in the West of Scotland from 1970 to 1995. Eye 1997;11:357–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haamann P , Jensen OM, Schmidt P. Changing indications for penetrating keratoplasty. Acta Ophthalmol 1994;72:443–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rapuano CJ, Cohen EJ, Brady SE, et al. Indications for and outcomes of repeat penetrating keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol 1990;109:689–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brooks AMV, Weiner JM. Indications for penetrating keratoplasty: A clinicopathological review of 511 corneal specimens. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1987;15:277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kervick GN, Shepherd WFI. Changing indications for penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmic Surg 1990;21:227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maeno A , Naor J, Lee HM, et al. Three decades of corneal transplantation: indications and patient characteristics. Cornea 2000;19:7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cursiefen C , Kuchle M, Naumann GOH. Changing indications for penetrating keratoplasty: Histopathology of 1,250 corneal buttons. Cornea 1998;17:468–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cobo LM, Coster DJ, Rice NSC, et al. Diagnosis and management of corneal transplantation for herpetic keratitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1980;98:1755–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barney NP, Foster CS. A prospective randomised trial of oral acyclovir after penetrating keratoplasty for herpes simplex viral keratitis. Cornea 1994;13:232–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tambasco FP, Cohen EJ, Nguyen LH, et al. Oral acyclovir after penetrating keratoplasty for herpes simplex keratitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1999;117:445–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacEwen CJ, Khan ZUH, Anderson E, et al. Corneal re-graft: indications and outcome. Ophthalmic Surgery 1988;19:706–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu E , Slomovic AR. Indications for penetrating keratoplasty in Canada, 1986–1995. Cornea 1997;16:414–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pouliquen Y . Doyne lecture keratoconus. Eye 1987;1:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaufman H , Barron B, McDonald M. The cornea. 2nd ed. Butterworth-Heinemann 1998:369.

- 29.Mamalis N , Anderson CW, Kreisler KR, et al. Changing trends in the indications for penetrating keratoplasty. Arch Ophthalmol 1992;110:1409–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Australian Corneal Graft registry, 1990–1992 report. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1993;21 (suppl 2) :1–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anwar M , Teichman KD. Big-bubble technique to bare Descemet’s membrane in anterior lamellar keratoplasty. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002;28:398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coombes AG, Kirwan JF, Rostron CK. Deep lamellar keratoplasty with lyophilised tissue in the management of keratoconus. Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:788–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melles GR, Remeijer L, Geerards AJ. A quick surgical technique for deep, anterior lamellar keratoplasty using visco-dissection. Cornea 2000;19:427–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balestrazzi E , Balestrazzi A, Mosca L, et al. Deep lamellar keratoplasty with trypan blue intrastromal staining. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002;28:929–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colin J , Cochener B, Savary G, et al. Correcting keratoconus with intracorneal rings. J Cataract Refract Surg 2000;26:1117–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Legeais J , Parc C, D’Hermies F. Nineteen years of penetrating keratoplasty in the Hotel-Dieu Hospital in Paris. Cornea 2001;20:603–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dobbins KRB, Price FW, Whitson WE. Trends in the indications for penetrating keratoplasty in the Midwestern United States. Cornea 2000;19:813–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krachmer JH, Palay DA. Cornea. St Louis, USA: Mosby, 1995.