Abstract

Aims: To estimate the risk of living in an institution and being visually impaired.

Methods: Two national surveys were pooled: (1) 2075 institutions (for children or adults with handicaps, old people, and psychiatric centres) were selected randomly, in 18 predefined strata, from the French health ministry files. From these institutions, 15 403 subjects were selected randomly and handicap was documented by interview in 14 603 (94.9%) of them; (2) level of handicap was documented in a randomised, stratified sample of 356 208 citizens living in the community; from this sample, 21 760 subjects were further selected at random and 16 945 people were interviewed. Data on handicaps (visual, auditory, speech, brain, visceral, motor, and other) and activities of daily living (ADL) were extracted. The odds ratio (OR) of living in an institution was estimated, using stepwise logistic regressions with age, geographical area, handicaps, and ADL as co-variables.

Results: Subjects in institutions, compared to those living at home, were, respectively, more often female (64.3% v 52.4%) and older (68.7 v 38.0 years); they more often had handicaps (ORs: speech, 6.59; brain, 10.17; motor, 8.86; visceral, 3.49; auditory, 2.66; other, 1.53); and were less often able to perform their ADL (46.2% v 97.1%) without assistance. Below 80 years, blind people were more often in institutions (ORs 0.239 to 0.306); whereas in older people the association was reversed (OR: 3.277). Low vision was always significantly associated with institutional residence (ORs from 0.262 to 0.752).

Conclusion: Visual handicap was associated with institutional residence. The link persisted after adjustment for known confounding factors.

Keywords: blindness, low vision, incapacity, dependency

An empirical analysis of life insurance contracts shows that mortality, in the future, is expected to fall further and quite rapidly.1 Today, the average life expectancy of an 80 year old in OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries extends to 7.3 years for men, and 8.9 years for women. In 2030 about one fourth of the population will be older than 65.

Population ageing is a challenge to policy makers in developed countries because it increases pressure on both social and care systems.2,3 Institutions are often the ultimate care facility for old people with many disabilities. In 2000 the proportion of subjects older than 65 years living in institutions ranged from 5% to 9% in developed countries.4 By 2020 the proportion will have increased by 56%. The social costs of old people in institutions ranged from 0.62% to 2.71% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2000. These costs are expected to rise by 69.5% in 2020.5 A highly desirable goal, therefore, is to decrease the demand for institutional care.

According to the most usual definition, a handicap or an incapacity affects nearly half the population over 65 years of age. Measurement of health status is difficult as life expectancy needs to be weighted by the degree of disability.6,7 Lastly, empirical results show that age, marital status, income, availability of help, and access to appropriate institutions affect the demand for institutional care.8–10

Blindness is one of the most severe disabilities to affect an individual, his/her family, and society.11 Some surveys have demonstrated the impact of blindness on daily living activities.12–16 The use of registers to estimate the prevalence of blindness is controversial as many blind subjects do not register.17–20 This necessitates dedicated surveys. The national prevalence of blindness and low vision among people living in institutions has never been compared with that in the general community. Since either blindness or low vision in the elderly can be a risk factor leading to institutional care, an adjusted comparison of prevalences in institutions and the community is a major requirement.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The data for this survey were gathered by the Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques (INSEE). The survey complied with all local regulations. The database was subsequently made available to the researchers for secondary analyses.

The community survey

A national census is performed approximately every 10 years in France. The country is divided into 26 regions, 100 counties, 4032 districts, and 36 679 cities. Groups of interviewers are responsible for specific geographical areas delimited in terms of city boundaries. Each household is visited by an interviewer assigned to the geographical area. Data are collected from each member of a family. All French citizens are questioned and obliged by French law to provide answers.

The purpose of the “Handicap Dependency” (HD) survey was to document handicap, incapacity and dependency, with no age limit, in French citizens living in the community throughout the nation.

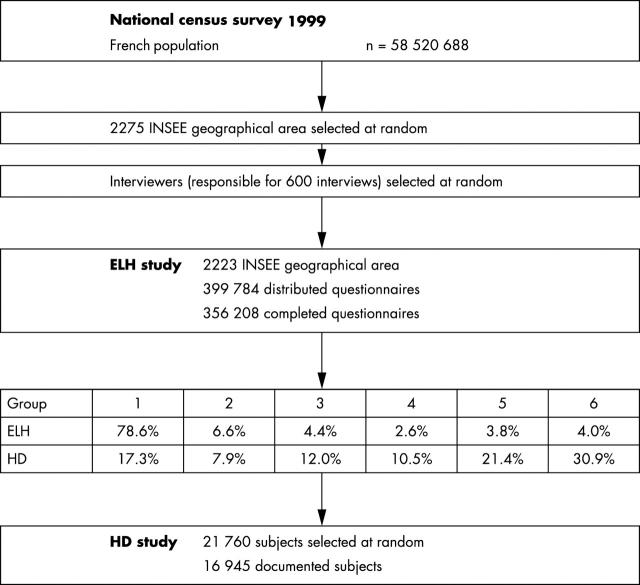

The design of this survey followed the guidelines and principles for developing disability statistics published by the United Nations.21 The sample (fig 1) was selected by a two step process.21,22

Figure 1.

Subject section—experimental design. INSEE, Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques; ELH, “Everyday Life and Health” survey; HD “Handicap Dependency” survey.

A previous national census survey was performed in 1990 which documented 57 831 816 citizens and provided statistics on geographical areas. A total of 2275 geographical areas were picked at random stratified by state, region, family, and socioprofessional statistics.

The 1999 national census added a filtering survey called “Everyday Life and Health” (ELH), comprising a self administered 18 item questionnaire which collected information on activities of daily living; 2223 of the 2275 geographical areas (97.7%) collaborated in the ELH survey. From the 399 784 questionnaires distributed, 359 010 were completed and returned. Questionnaires were to be completed by all members of a household.

Following ELH, the HD survey quantified handicaps and dependencies. Subjects from the ELH survey were clustered into six handicap groups ranging from “no handicap” (group 1) to “severe handicap” (group 6), based upon a handicap severity score.23 To describe the consequences of handicap in detail, subjects in the severe handicap group had a higher probability of being questioned in the HD survey. Face to face interviews were available for 16 945 of the 21 760 subjects selected at random from the ELH respondents.

Response rates were 89.1% (ELH) and 77.8% (HID). In the HID survey, 12% of households refused to answer, 7.3% were not accessible (interviews were conducted just after the great French storm of 1999), 0.7% of subjects had died since the 1999 national census, and 0.5% were living in institutions. Weights for national extrapolation were calculated: (1) according to the 1999 national census results23 for the ELH survey; and (2), on the basis of the ELH handicap severity classification, refusal to participate in the HD survey, age, sex, size of household, type of household, and geographical area size, for the HD survey.

The institution survey

French institutions are classified in four categories (table 1) and 18 strata. Institutions were selected at random from French health ministry files. The probability of selecting an institution was inversely proportional to the number of institutions in its stratum and proportional to its number of beds. The interviewers selected eight subjects at random from the residents list.

Table 1.

Experimental design, sampling plan, and strata description

| Population | Sample | |||

| No of subjects | No of institutions | No of subjects | No of institutions | |

| Child institutions | 48 398 | 1206 | 3300 | 413 |

| Intellectual handicaps | 39 605 | 1053 | 2200 | 275 |

| Motor handicaps | 3582 | 74 | 550 | 69 |

| Sensory handicaps | 5311 | 79 | 550 | 69 |

| Adult institutions | 82 852 | 2405 | 3590 | 449 |

| Able to work outside the institution | 43 416 | 1258 | 1600 | 200 |

| Able to work inside the institution | 22 430 | 661 | 1000 | 125 |

| Need for medical assistance | 11 065 | 290 | 550 | 69 |

| Other | 5941 | 196 | 440 | 55 |

| Psychiatric institutions | 70 932 | 394 | 2500 | 312 |

| Mental disease, specialised hospitals | 46 818 | 167 | 1200 | 150 |

| Psychiatric hospitals | 10 870 | 38 | 280 | 35 |

| Other | 13 244 | 197 | 1020 | 127 |

| Institutions for the aged | 490 963 | 7414 | 7100 | 887 |

| Private—intense medical activities | 32 049 | 463 | 600 | 75 |

| Private—mild medical activities | 59 552 | 795 | 800 | 100 |

| Charity—no medical activities | 48 056 | 1128 | 800 | 100 |

| Private—no medical activities | 61 311 | 1386 | 1000 | 125 |

| Public long term | 75 447 | 962 | 1000 | 125 |

| Public—intense medical activities | 93 172 | 1023 | 1100 | 137 |

| Public—mild medical activities | 86 720 | 1028 | 1100 | 137 |

| Public—no medical activities | 34 656 | 629 | 700 | 88 |

A total of 2075 institutions were selected in 1998, 14 more than scheduled. Fifty seven institutions were replaced: 37 because they had no residents, seven because the survey was not technically possible, and 18 because they no longer existed. In addition, 155 institutions (7.5%) refused to participate. The refusal rate varied between types of institution: handicapped child 6.5%, handicapped adult 4.5%, old people 4.5%, and psychiatric 17.0%. The most frequent reasons for refusing to participate were lack of time (22.7%), the non-compulsory nature of the survey (10.7%), lack of staff to help the interviewer (7.3%), residents’ tranquillity (5.3%), institution being restructured (3.3%), violation of privacy (2.7%), too many surveys (2.7%), and a questionnaire not suited to residents (2.7%).

Interviews were conducted with 14 611 (94.9%) of the 15 403 randomly selected subjects. The analyses were based on 14 603 patients whose handicap was documented (eight interviews stopped before handicap documentation).

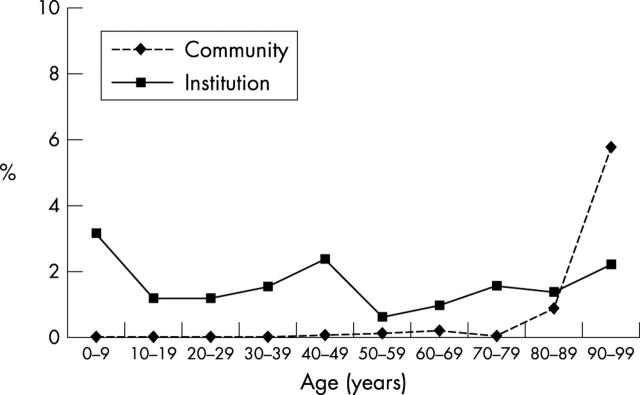

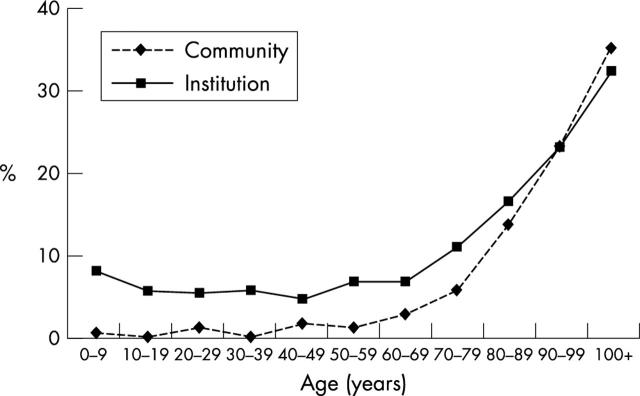

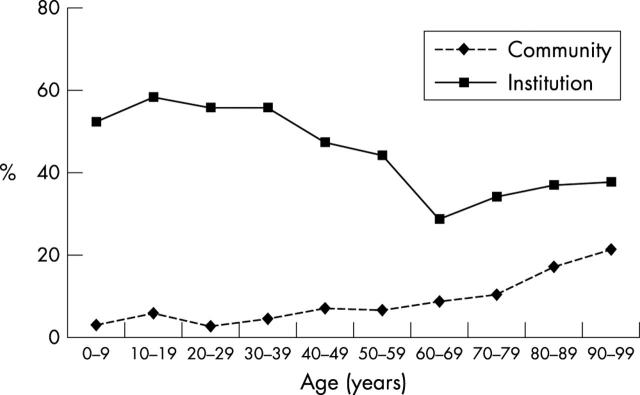

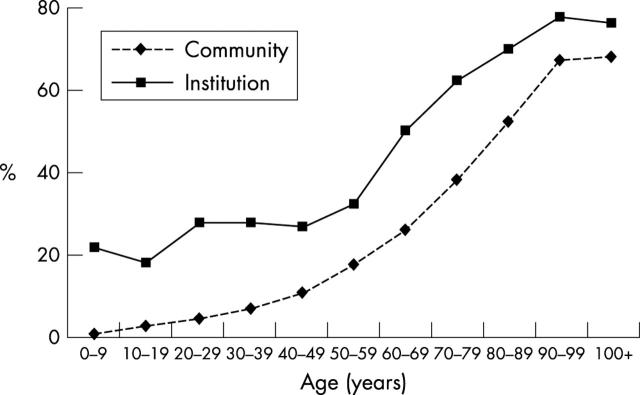

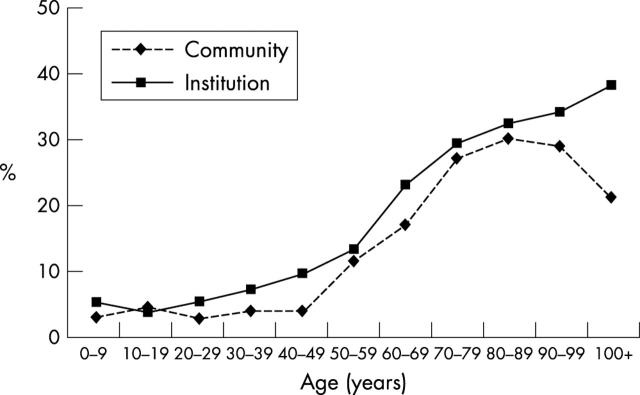

The prevalence of blindness was less than low vision (figs 3 and 4), whatever the age, but the prevalence of both increased as people became older, especially older than 80 years. The prevalence of blindness and low vision was higher in institutions, than in the community, among people below 90 years of age.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of blindness in institutions and the community according to age by decade.

Figure 4.

Prevalence of low vision in institutions and the community according to age by decade.

Weights for national extrapolation included stratum size, the institution’s occupation rate (number of subjects in the institution/number of available beds), and the rate of refusal to answer (higher in psychiatric centres).

Data collected

The data include types of handicap and disabilities, rated activities of daily living (Katz, Colvez, and EHPA scales), family environment, subjects’ social demography, and institution characteristics. There was no medical input. If interviewers came across diseases or other health problems not mentioned previously, during the rest of the questionnaire, they recorded them. Data were recorded in freehand and the declared condition was classified post hoc by medical coding experts.

Handicap was identified by an initial “yes/no” question, as follows: “In everyday life, are you faced with physical, sensory, intellectual, or mental difficulties (resulting from an accident, chronic disease, a birth problem, disability, ageing …)?” The following question was asked to list handicaps: “What kind of difficulties, disabilities, or other health problems do you suffer from?” Eight classes of handicap were selected: auditory, low vision, blindness, brain, motor, speech, visceral, and other.

For the purpose of this study, blindness and low vision were taken as stated by the subject. Three specific questions applied to vision: (1) Do you have trouble reading newspapers or books, etc … (using spectacles or contact lenses if you normally wear them)? (2) Do you have trouble recognising the features of someone standing 4 metres away (using spectacles or contact lenses, if you normally wear them)? (3) Would you say that you are completely blind (light perception), partially blind (still form perception), or visually impaired? Subjects were classified as (1) blind; (2) having low visual acuity; or (3) control, according to their answers when questioned. The aim was to classify subjects as “blind” if they declared their vision to be light perception, at best. Low vision subjects declared shape perception, at best, or reported severe limitations in performing short distance visual activities, long distance visual activities, or both.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted with SAS (SAS Institute, NC, USA), release 8.2. Weights were calculated by INSEE. Analysis of variance was used for continuous variables to compare subpopulations, and χ2 for qualitative variables. A weighted stepwise logistic regression was used to adjust for confounding factors. Model entry and exit p values were fixed at 0.10. Two odds ratios (ORs) were adjusted on handicap, age, activities of daily living, and geographical region. They compared the low vision and blind groups with a control population. Geographical region was chosen as a confounding factor to take into account the inequities of institution supply (number and type of institutions) and demand (mainly demographic). ORs with their 95% confidence limits are presented for all variables except region. All tests were interpreted two sided with alpha fixed at 0.05. No corrections were applied to take into account test multiplicity.

RESULTS

Extrapolation of the data to the national level indicated that 664 253 of 58 096 060 subjects (1.14%) lived in institutions (table 2). People living in institutions were, respectively, older (68.7 v 38.0 years) and less frequently male (35.7% v 48.6%); and were more often alone (92.3% v 35.8%), the major reason for the last being widowhood. The greatest proportion of people in institutions had retired, more so than in the community (57.1% v 18.5%, respectively). The job skill categories of those in institutions were somewhat less than for people in the community, as shown by the following percentages: work exempt people (3.6% v 10.1%), intermediary workers (7.7% v 15.2%), and employees (15.7% v 11.0%).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic parameters according to life status

| Citizens living at home (n = 16 945) | Citizens in institutions (n = 14 603) | All (n = 58 096 060) | |

| Age group (nationwide extrapolation) | (n = 57 431 807) | (n = 664 253) | |

| Mean age (years) | 38.0 | 68.7 | 38.3 |

| 0–9 | 12.7% | 0.8% | 12.6% |

| 10–19 | 13.0% | 6.4% | 13.0% |

| 20–29 | 13.3% | 4.9% | 13.2% |

| 30–39 | 14.9% | 6.2% | 14.8% |

| 40–49 | 14.4% | 5.7% | 14.3% |

| 50–59 | 11.6% | 3.8% | 11.5% |

| 60–69 | 9.4% | 7.1% | 9.4% |

| 70–79 | 7.7% | 15.0% | 7.8% |

| 80–89 | 2.6% | 31.5% | 3.0% |

| 90–99 | 0.5% | 18.2% | 0.7% |

| 100+ | <0.01% | 0.5% | 0.01% |

| Sex (male%) | 48.6% | 35.7% | 48.5% |

| Age >15, living without relative | 35.8% | 92.3% | 63.5% |

| Age >15, marital status | |||

| Never married | 30.5% | 39.2% | 30.7% |

| Married | 55.7% | 8.1% | 55.1% |

| Widowed | 7.4% | 47.1% | 8.0% |

| Divorced | 5.1% | 4.9% | 5.1% |

| Separated | 1.3% | 0.8% | 1.3% |

| Job category | |||

| Farmer | 10.7% | 7.9% | 10.7% |

| Artisan, shopkeeper, company owner | 11.4% | 7.8% | 11.3% |

| Management | 10.1% | 3.6% | 10.1% |

| Intermediary worker | 15.2% | 7.7% | 15.1% |

| Employee | 11.0% | 15.7% | 11.0% |

| Worker | 35.7% | 32.9% | 35.6% |

| No professional activities | 3.7% | 15.3% | 3.8% |

| Unclassified | 2.3% | 9.2% | 2.4% |

| Job status | |||

| Active | 40.8% | 6.9% | 40.4% |

| Unemployed | 4.8% | 0.7% | 4.7% |

| In training | 8.0% | 3.1% | 7.9% |

| Military | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.2 |

| Retired | 18.5% | 57.1% | 19.0% |

| Not working | 27.9% | 32.2% | 28.0% |

More than 90% of people living in institutions (table 3) reported daily difficulties (mental, physical, intellectual, or sensory) compared with less than one third in the community. According to the Colvez mobility index, 70.0% of people living in institutions needed assistance in contrast with 96.6% in the community who did not. The Katz index showed that 46.2% of people living in institutions could perform all activities, compared to 97.1% of those in the community.

Table 3.

Handicap parameters according to living status. Psychiatric dependence is defined as partially incoherent and sometime disorientated, totally incoherent, or always disorientated. Activities of daily living: self washing, dressing, using the restroom, getting out of a bed or a seat, controlling sphincters, eating meals already prepared

| Citizens living at home (n = 57 431 807) | Citizens in institutions (n = 693 245) | All (OR) (n = 58 125 052) | |

| Daily difficulties (mental, physical, intellectual, sensory) | 31.7% | 92.2% | 32.4% |

| Colvez mobility index | |||

| Restricted to bed | 0.2% | 19.0% | 0.5% |

| Help for toilet | 1.8% | 31.5% | 2.2% |

| Help to go outside | 1.4% | 19.5% | 1.6% |

| None of these assistance | 96.6% | 30.0% | 95.8% |

| Long term institution index | |||

| Psychiatrically dependent | |||

| Restricted to bed | 0.2% | 16.4% | 0.4% |

| Help for toilet | 0.6% | 22.7% | 0.9% |

| Help to go outside | 0.4% | 7.5% | 0.5% |

| None of these assistance | 8.3% | 3.2% | 8.2% |

| Not psychiatrically dependent | |||

| Restricted to bed | 0.1% | 2.6% | 0.1% |

| Help for toilet | 1.2% | 8.8% | 1.3% |

| Help to go outside | 1.0% | 12.0% | 1.1% |

| None of these assistance | 88.3% | 26.9% | 87.5% |

| Katz (activities of daily living) | |||

| A Independent for the 6 activities | 97.1% | 46.2% | 96.4% |

| B Dependent for only one activities | 1.8% | 9.8% | 1.9% |

| C Dependent for 2 activities, including the first | 0.4% | 6.5% | 0.5% |

| D Dependent for 3 activities, including the 2 first | 0.2% | 4.1% | 0.2% |

| E Dependent for 4 activities, including the 3 first | 0.2% | 6.0% | 0.2% |

| F Dependent for 5 activities, including the 4 first | 0.1% | 10.2% | 0.3% |

| G Dependent for the 6 activities | 0.1% | 7.8% | 0.2% |

| H Dependent for at least 2 activities, but neither C, D, E, nor F | 0.1% | 9.4% | 0.2% |

| Handicaps | |||

| Auditory | 7.1% | 16.8% | 7.2% (2.66) |

| Low vision | 2.0% | 13.4% | 2.1% (table 4) |

| Blind | 0.1% | 1.6% | 0.1% (table 4) |

| Brain | 6.4% | 40.9% | 6.8% (10.17) |

| Motor | 12.9% | 56.8% | 13.4% (8.86) |

| Speech | 0.9% | 5.9% | 1.0% (6.59) |

| Visceral | 8.7% | 25.0% | 8.9% (3.49) |

| Other | 18.9% | 26.3% | 19.0% (1.53) |

In the institution survey, 265 of 14 603 interviewed subjects were classified as blind, 1622 had low vision, and 12 716 did not declare a visual handicap (table 3). Upon extrapolation to the whole population of 664 252 subjects living in institutions, the corresponding prevalence figures were 10 394 blind individuals (1.56%), 89 252 with low vision (13.4%). In the community study, 87 of 16 945 interviewed subjects were classified as blind, 1126 had low vision, and 1061 claimed a visual problem. Upon extrapolation to the whole population living in the community, the corresponding prevalence figures were 57 959 blind individuals (0.10%), 1 116 862 with low vision (1.94%), and 1 672 111 with other visual problems.

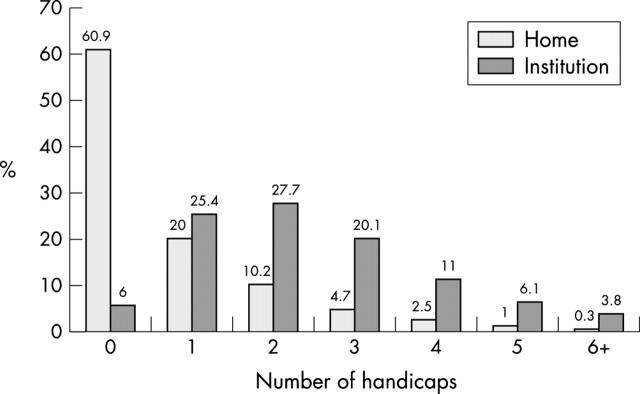

Over 40% of subjects in institutions possessed three or more handicaps (fig 2), which contrasts markedly with 60.9% of people in the community without handicap.

Figure 2.

Distribution of handicapped subjects living at home and in institutions.

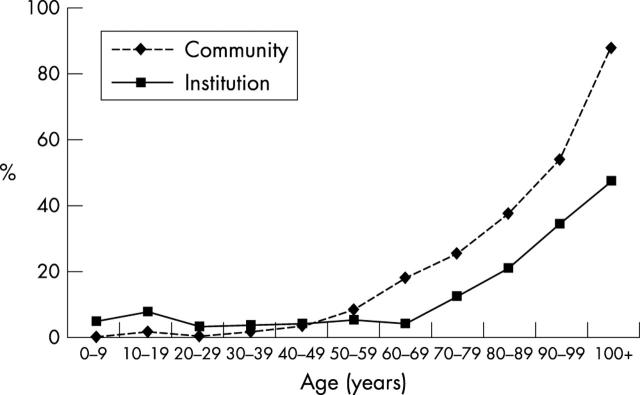

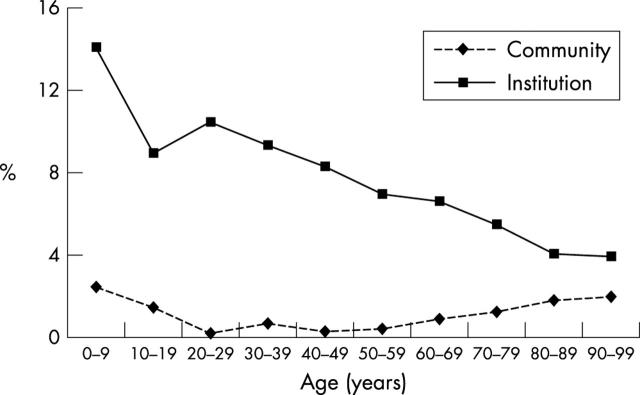

In both institutions and the community (figs 3–9), the prevalence of low vision was far below that of auditory, brain, motor, or visceral handicap. On comparing the different prevalence rates, between institution and community subjects over successive decades, it appears that brain and motor handicaps were the main contributors to the predominantly institutional cases.

Figure 9.

Prevalence of brain handicaps in institutions and the community according to age by decade.

Before adjustment the OR for the blind population increased (table 4) with age, starting at very low values (OR = 0.009) at ages less than 40 and coming close to unity (OR = 0.907) at ages greater than 80. Similar results were obtained with low vision subjects over a narrower range of values (ORs from 0.097 to 0.752).

Table 4.

Logistic regression. Probability of being in an institution when blind or with low vision adjusted on age, other handicaps, activities of daily living, and region. Definitions of activities of daily living are shown in table 3

| OR | 0<age <40 | p Value | OR | 40<age<60 | p Value | OR | 60<age<80 | p Value | OR | Age>80 | p Value | |

| 95% CL | 95% CL | 95% CL | 95% CL | |||||||||

| Blind unadjusted | 0.009 | 0.008 to 0.010 | <0.0001 | 0.043 | 0.040 to 0.046 | <0.0001 | 0.094 | 0.089 to 0.098 | <0.0001 | 0.907 | 0.881 to 0.933 | <0.0001 |

| Low vision unadjusted | 0.097 | 0.095 to 0.100 | 0.271 | 0.262 to 0.280 | 0.405 | 0.398 to 0.412 | 0.752 | 0.745 to 0.759 | ||||

| Blind adjusted | 0.239 | 0.220 to 0.260 | <0.0001 | 0.232 | 0.213 to 0.253 | <0.0001 | 0.306 | 0.288 to 0.325 | <0.0001 | 3.277 | 3.165 to 3.392 | <0.0001 |

| Low vision adjusted | 0.262 | 0.253 to 0.270 | 0.499 | 0.480 to 0.518 | 0.632 | 0.620 to 0.645 | 0.848 | 0.838 to 0.858 | ||||

| Auditory | 0.412 | 0.404 to 0.427 | <0.0001 | 2.074 | 1.990 to 2.162 | <0.0001 | 2.827 | 2.775 to 2.879 | <0.0001 | 2.055 | 2.034 to 2.076 | |

| Brain | 0.047 | 0.046 to 0.048 | <0.0001 | 0.146 | 0.143 to 0.148 | <0.0001 | 0.473 | 0.466 to 0.479 | <0.0001 | 0.931 | 0.922 to 0.941 | <0.0001 |

| Speech | 0.415 | 0.404 to 0.427 | <0.0001 | 2.074 | 1.990 to 2.162 | <0.0001 | 1.214 | 1.181 to 1.248 | <0.0001 | 0.789 | 0.768 to 0.811 | <0.0001 |

| Visceral | 4.827 | 4.687 to 4.970 | <0.0001 | 1.661 | 1.614 to 1.709 | <0.0001 | 1.301 | 1.284 to 1.318 | <0.0001 | 0.933 | 0.924 to 0.942 | <0.0001 |

| Motor | 0.558 | 0.548 to 0.568 | <0.0001 | 1.526 | 1.492 to 1.560 | <0.0001 | 0.805 | 0.795 to 0.815 | <0.0001 | 0.886 | 0.877 to 0.895 | <0.0001 |

| Other | 0.149 | 0.147 to 0.151 | <0.0001 | 0.243 | 0.239 to 0.247 | <0.0001 | 1.132 | 1.118 to 1.146 | <0.0001 | 4.609 | 4.556 to 4.663 | <0.0001 |

| Age | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| 0–10 | 6.041 | 5.845 to 6.244 | ||||||||||

| 10–20 | 0.900 | 0.886 to 0.915 | ||||||||||

| 20–30 | 0.888 | 0.874 to 0.903 | ||||||||||

| 30–40 | Ref | |||||||||||

| 40–50 | 0.785 | 0.771 to 0.799 | ||||||||||

| 50–60 | Ref | |||||||||||

| 60–70 | 1.892 | 1.870 to 1.915 | ||||||||||

| 70–80 | Ref | |||||||||||

| 80–90 | 2.290 | 2.267 to 2.314 | ||||||||||

| 90 + | Ref | |||||||||||

| Activity of daily living | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| A | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| B | 0.111 | 0.108 to 0.114 | 0.227 | 0.220 to 0.235 | 0.190 | 0.186 to 0.194 | 0.408 | 0.402 to 0.414 | ||||

| C | 0.101 | 0.098 to 0.105 | 0.031 | 0.030 to 0.033 | 0.082 | 0.080 to 0.084 | 0.372 | 0.366 to 0.379 | ||||

| D | 0.048 | 0.046 to 0.050 | 0.063 | 0.060 to 0.067 | 0.090 | 0.087 to 0.093 | 0.229 | 0.225 to 0.234 | ||||

| E | 0.067 | 0.064 to 0.070 | 0.072 | 0.068 to 0.077 | 0.032 | 0.031 to 0.033 | 0.129 | 0.126 to 0.132 | ||||

| F | 0.040 | 0.038 to 0.042 | 0.015 | 0.014 to 0.016 | 0.019 | 0.018 to 0.020 | 0.070 | 0.069 to 0.071 | ||||

| G | 0.123 | 0.118 to 0.129 | 0.010 | 0.009 to 0.011 | 0.022 | 0.021 to 0.022 | 0.056 | 0.055 to 0.057 | ||||

| H | 0.023 | 0.022 to 0.024 | 0.018 | 0.017 to 0.019 | 0.017 | 0.016 to 0.018 | 0.052 | 0.051 to 0.053 |

Regions OR estimates not shown.

After adjustment ORs came closer to unity, but still remained statistically significant. Blindness was more often associated with institutions (ORs from 0.239 to 0.306), except for people above 80 years of age for whom the ORs reversed (3.277). Low vision was associated with institutional residence at all ages and increased with age (ORs from 0.262 to 0.848).

Strong associations were found with two handicaps. People with brain handicaps were more often in institutions, whereas subjects with visceral handicaps were more often in the community. A very strong association was found between institutions and level of dependence as measured by the Katz index—that is, the probability of living in an institution increased with the number of activities requiring assistance.

DISCUSSION

Strong associations were found between living conditions, activities of daily living, and handicap, on the one hand, and institutional residence, on the other. Clearly, institutional care was one way to cope with the day to day difficulties that resulted from social and health handicaps throughout the lifespan of French citizens.

Blindness and low vision, two of the handicaps collected by both surveys reported here, had prevalences far below other types of handicap. Before adjustment, blindness and low vision were strongly associated with institutions. It was shown, however, that blindness and low vision are independent factors associated with institutional residence. They were independent of the following concomitant factors: other handicaps, age, activities of daily living, and the availability of institutional care throughout France.

Beyond the age of 80 years, the ORs associated with blindness and low vision varied between 1.58 and 4.31. Above 80 years most ORs came closer to unity including even the item most associated with institutions—the Katz index. In this age group, handicap and activities of daily living were less strongly associated with institutions. With advanced age, individuals were more frequently handicapped, depressed or psychologically disturbed and could over-declare their handicap, which might explain the previous finding. Further research should be conducted in this subgroup to understand the factors leading to institutional residence.

The surveys shared two limitations: (1) their cross sectional design did not permit an analysis of possible causal relations between blindness, low vision, handicap, dependency, incapacity, and residence in institutions; and (2) the visual acuity of those who responded to the survey was neither measured nor controlled by ophthalmologists. Subjects classified as blind self declared that they could not perceive shapes. This may be a serious limitation to our analysis, although our prevalence figures are close to the sole report found in the international literature.

This is the first study to compare the prevalence, at a national level, of declared low vision and blindness across all ages, between subjects living in the community and in institutions. Low vision and blindness were found to be highly associated with institutional residence. The following consequences arise from this result: (1) treatments or procedures which would avoid, or postpone, low vision and blindness might reduce the demand for institutional care; (2) the visual health care delivered to subjects in institutions must adapt to the changing requirements of an ageing population; and (3) the economic evaluation of visual impairment should not be restricted to medical costs alone, but needs to embrace the entire social dimension.

Figure 5.

Prevalence of motor handicaps in institutions and the community according to age by decade.

Figure 6.

Prevalence of auditory handicaps in institutions and the community according to age by decade.

Figure 7.

Prevalence of speech handicaps in institutions and the community according to age by decade.

Figure 8.

Prevalence of visceral handicaps in institutions and the community according to age by decade.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Irène Fournier and Benoit Riandey for the database. Alcon Research Ltd employed Gilles Berdeaux.

Abbreviations

ADL, activities of daily living

GDP, gross domestic product

INSEE, Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques

OR, odds ratio

REFERENCES

- 1.Mullin C, Philipson T. The future of old-age longevity: competitive pricing of mortality contingent claims. NBER working paper No 6042. 1997.

- 2.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Aging in OECD countries. A critical policy challenge. Social Policy study No 20, Paris: OECD, 1997.

- 3.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Maintaining propriety in an Aging Society. Paris: OECD, 1998.

- 4.Jacobzone S, Cambois E, Chaplain E, et al.The health of older persons in OECD countries: is it improving fast enough to compensate for population aging? Labour market and social policy occasional papers. Paris: OECD, 1998.

- 5.Jacobzone S. Ageing and care for frail elderly persons: an overview of international perspectives. Labour market and social policy—Occasional papers No 38. Paris: OECD, 1999.

- 6.Mathers C. Developments in the use of health expectancy indicators for monitoring and comparing the health of populations. Background paper for the OECD. Paris: OECD, 1997.

- 7.Robine JM. Présentation comparée des espérances de santé et des DALYs. Background paper prepared for the OECD. Paris: OECD, 1997.

- 8.Carrière Y. Pelletier L. Factors underlying the institutionalization of elderly persons in Canada. The Gerontologist 1995;50 (B 3) :S164–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crevitts P, De Donder P. Analyse des déterminants de la demande de soins et services des personnes agées. Groupe de recherche en économie du bien ëtre. Namur, Belgium: Facultés universitaires,.

- 10.Himes CL. A comparative analysis of nursing home entry in Germany and the United States, Syracuse university, Ruhr University Bochum, paper presented at the aging conference. Amsterdam, 1997.

- 11.Goldstein H. The reported demography and causes of blindness throughout the world. Adv Ophthalmol 1980;40:1–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haymes SA, Johnston AW, Heyes AD. A weighted version of the Melbourne low-vision ADL index: a measure of the disability impact. Optom Vis Sci 2001;78:565–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haymes SA, Johnston AW, Heyes AD. Relationship between vision impairment and ability to perform activities of daily living. Ophthal Physiol Opt 2002;22:79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szlyk JP, Seiple W, Fishman GA, et al. Perceived and actual performance of daily tasks: relationship to visual function tests in individuals with retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology 2001;108:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams RA, Brody BL, Thomas RG, et al. The psychological impact of macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116:514–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright SE, McCarty CA, Burgess M, et al. Vision impairment and handicap: the RVIB employment survey. The steering committee for the RVIB employment survey. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1999;27:204–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson R, Deutsch J, Jones HS, et al. Unrecognised and unregistered visual impairment. Br J Ophthalmol 1994;78:736–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruce IW, McKennell AC, Walker EC. Blind and partially sighted adults in Britain: the RNIB survey. Vol 1. London: HMSO, 1991.

- 19.Walker EC, Tobin MJ, McKennell AC. Blind and partially sighted children in Britain: the RNIB Survey. Vol 2. London: HMSO, 1992.

- 20.Wormald R, Evans J. Registration of blind and partially sighted people. Br J Ophthalmol 1994;78:736–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United Nations. Manual for the development of statistical information for disability programmes and policies. United Nations Publication, Sales No E96.XVII.4. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Statistics Division 1996.

- 22.Morniche P. L’enquête HID de l’INSEE—Objectifs et shéma organisationnel. Courrier des Statistiques. Paris: Ed INSEE, 1998:87, 88.

- 23.Couet C. Estimations locales dans le cadre de l’enquête HID. Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economique. Séries des documents de travail de la Direction des statistiques démographiques et sociales. No F0207. Paris, Ed INSEE, 2002 (www.insee.fr).