We present a large comparative series of trypan blue use in cataract surgery. This series of trypan blue used in all eyes regardless of cataract severity may be unique. We found an apparent increased rate of cystoid macular oedema (CMO) associated with trypan blue use.

Melles et al’s1 report on the use of trypan blue in cataract extraction in 1999 combined with Apple et al’s2–4 series on dye enhanced cataract surgery facilitated widespread acceptance of this technique. The dye has been shown to stain basement membrane of lens capsule.5 Trypan blue is now widely used to assist in cataract extraction when visualisation of the anterior capsule is poor because of loss of red reflex. Trypan blue has also been used to improve contrast during cataract extraction in eyes with corneal opacities6 and to stain internal limiting membrane and epiretinal membrane during vitreoretinal surgery.7,8 The safety profile of trypan blue appears good with no adverse effects reported in several large series.9–11

Patients and methods

In this retrospective, comparative study we identified a consecutive series of 75 patients (group A) in whom trypan blue had been used “routinely” regardless of cataract type or density. A consecutive series of 94 patients (group B) who had routine phacoemulsification by the same surgeon were used as a control group.

Apart from the use of trypan blue to facilitate capsulorhexis, standard phacoemulsification techniques were used in both groups.

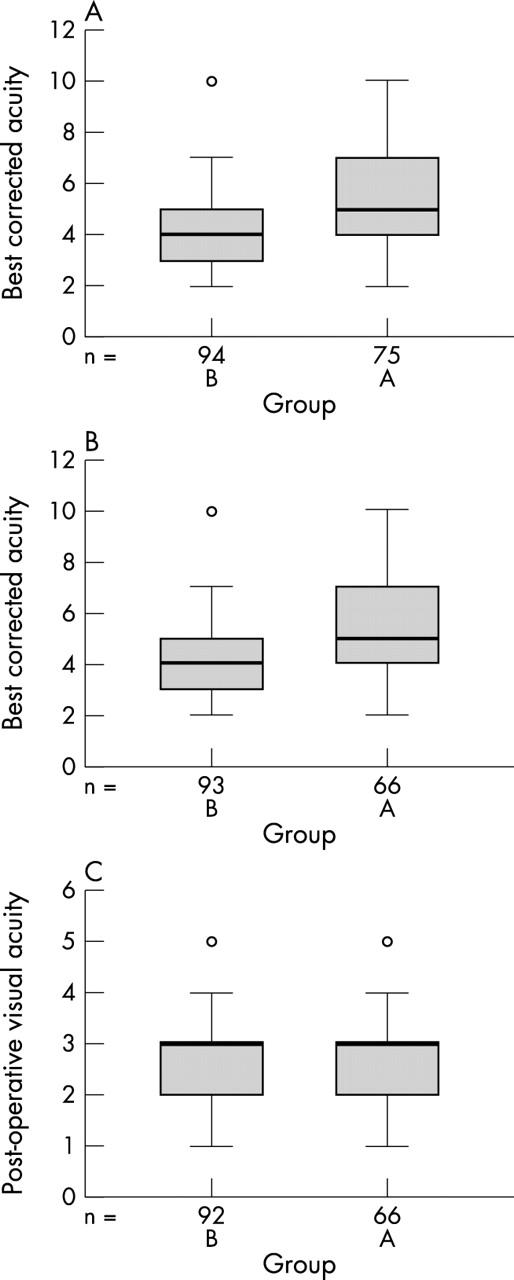

The data from the two cohorts were compared using mean and standard deviations for continuous variables such as age, and proportions for categorical variables such as sex. For acuity a numeric ordinal score was created from 1 to 10 by placing all the recorded acuities in order. This numeric ordinal score allowed us to plot the data using box plots, and to analyse the data using non-parametric methods to produce p values where necessary.

Results

The two groups compared favourably with regard to age and sex (table 1) but the preoperative best corrected acuity was worse in group A (fig 1A). Group A also had a higher proportion of patients with ocular co-morbidity (table 1).

Table 1.

Age and sex distribution and co-morbidity

| Variable | Group A (n = 75) | Group B (n = 94) |

| Mean age (SD) | 79.4 (9.8) | 78.4 (8.5) |

| Sex: | ||

| Male | 25 (33.3%) | 31 (33%) |

| Female | 50 (66.7%) | 63 (67%) |

| ARMD | 7 | 1 |

| CVA | 1 | 0 |

| ERM | 1 | 0 |

ARMD, age related macular degeneration; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; ERM, epiretinal membrane.

Figure 1.

(A) Preoperative best corrected acuity (group A = 75, group B = 94); (B) preoperative acuity without co-morbidity (group A = 66, group B = 93); (C) postoperative acuity without co-morbidity. Acuity key: 6/5 = 1; 6/6 = 2; 6/9 = 3; 6/12 = 4; 6/18 = 5; 6/24 = 6; 6/36 = 7; 6/60 = 8; 2/60 = 9; <2/60 = 10.

If all the cases with co-morbidity are removed from both groups, the preoperative best corrected acuity remains worse in group A, suggesting that the cataracts in this group were visually of greater significance (fig 1B).

There were four patients with clinically apparent CMO in group A and no cases in group B. The CMO was confirmed in all cases by the vitreoretinal specialist (PRS) using standard biomicroscopy techniques with a fundal contact lens. The incidence of clinically apparent CMO was 5.3% in group A and 0% in group B (p = 0.037).

All cases of CMO were treated with a combination of topical steroid and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drops and resolved completely with good visual outcomes.

The postoperative acuities compared favourably in both groups after patients with co-morbidity were removed from both groups (fig 1C).

Comment

Cystoid macular oedema resulting in visual loss occurs in up to 3.8% of cases following cataract extraction by phacoemulsification without posterior capsule rupture12,13 and up to 13% of cases with posterior capsule rupture.14,15 Ursell et al16 demonstrated an incidence of angiographic CMO of 19% following phacoemulsification (none of the patients in this group had clinically apparent CMO).

CMO has not been reported as a result of trypan blue use, but trypan blue has been shown to cause damaged photoreceptors in rabbit eyes after intravitreal injection.17 Trypan blue has also been shown to be carcinogenic and teratogenic in animal studies.18,19 The clinical significance or relevance to a human population of the animal studies is uncertain.

Trypan blue has been shown to inadvertently stain posterior capsule20 and intraocular lens implants.21,22

None of the patients in our group who developed CMO had associated posterior capsule rupture or ocular co-morbidity and all of the cases were treated successfully with good visual outcomes.

Dada et al23 and Sharma et al24 suggested the use of trypan blue in routine cases to aid in training of junior surgeons. Our study would suggest some caution with this approach in view of the apparent increase in the incidence of CMO with trypan blue use.

The preoperative best corrected acuity was decreased in the group in which trypan blue was used. This suggests that the cataracts in this group were of greater density, possibly requiring more energy to remove using phacoemulsification. The energy used during surgery however was not recorded. The CMO may therefore be a reflection of higher energy used in denser cataract.

A prospective trial with matched cohorts is required to prove the suggested higher incidence of CMO with trypan blue use. OCT scanning of the maculas in both groups would give non-invasive objective evidence of CMO.

We suggest the following steps to limit the apparent complication of CMO with trypan blue use:

Use the smallest amount and lowest concentration of trypan blue possible (trypan blue in concentrations as low as 0.0125% has been shown to effectively stain the anterior capsule25)

Increase postoperative steroid or anti-inflammatory drops prophylactically

Use only in appropriate cases—that is, with poor visualisation of the anterior capsule.

References

- 1.Melles GR, de Waard PW, Pameyer JH, et al. Trypan blue capsule staining to visualize the capsulorhexis in cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999;25:7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pandey SK, Werner L, Escobar-Gomez M, et al. Dye-enhanced cataract surgery. Part 1: Anterior capsule staining for capsulorhexis in advanced/white cataract. J Cataract Refract Surg 2000;26:1052–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werner L, Pandey SK, Escobar-Gomez M, et al. Dye-enhanced cataract surgery. Part 2: Learning critical steps of phacoemulsification. J Cataract Refract Surg 2000;26:1060–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pandey SK, Werner L, Escobar-Gomez M, et al. Dye-enhanced cataract surgery. Part 3: Posterior capsule staining to learn posterior continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis. J Cataract Refract Surg 2000;26:1066–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh AJ, Sarodia UA, Brown L, et al. A histological analysis of lens capsules stained with trypan blue for capsulorrhexis in phacoemulsification cataract surgery. Eye 2003;17:567–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhartiya P, Sharma N, Ray M, et al. Trypan blue assisted phacoemulsification in corneal opacities. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86 (8) :857–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perrier M, Sebag M. Trypan blue-assisted peeling of the internal limiting membrane during macular hole surgery. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;135:903–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li K, Wong D, Hiscott P, et al. Trypan blue staining of internal limiting membrane and epiretinal membrane during vitrectomy: visual results and histopathological findings. Br J Ophthalmol 2003;87:216–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacob S, Agarwal A, Agarwal A, et al. Trypan blue as an adjunct for safe phacoemulsification in eyes with white cataract. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002;28:1819–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melles GR, de Waard PW, Pameijer JH, et al. [Staining the lens capsule with trypan blue for visualizing capsulorhexis in surgery of mature cataracts]. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 1999;215:342–4 (In German). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Dooren BT, de Waard PW, Poort-van Nouhuys H, et al. Corneal endothelial cell density after trypan blue capsule staining in cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002;28:574–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malik AR, Qazi ZA, Gilbert C. Visual outcome after high volume cataract surgery in Pakistan. Br J Ophthalmol 2003;87:937–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riley AF, Malik TY, Grupcheva CN, et al. The Auckland Cataract Study: co-morbidity, surgical techniques, and clinical outcomes in a public hospital service. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:185–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan FA, Mathur R, Ku JJK, et al. Short-term outcomes in eyes with posterior capsule rupture during cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29 (3) :537–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blomquist PH, Rugwani RM. Visual outcomes after vitreous loss during cataract surgery performed by residents. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002;28:847–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ursell PG, Spalton DJ, Whitcup SM, et al. Cystoid macular edema after phacoemulsification: relationship to blood-aqueous barrier damage and visual acuity. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999;25:1492–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veckeneer M, van Overdam K, Monzer J, et al. Ocular toxicity study of trypan blue injected into the vitreous cavity of rabbit eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2001;239:698–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung KT. The significance of azo-reduction in the mutagenesis and carcinogenesis of azo dyes. Mutat Res 1983;114:269–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ema M, Kanoh S. Studies on the pharmacological bases of fetal toxicity of drugs. Effect of trypan blue on pregnant rats and their offspring. Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi 1982;79:369–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birchall W, Raynor MK, Turner GS. Inadvertent staining of the posterior lens capsule with trypan blue dye during phacoemulsification. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:1082–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werner L, Apple DJ, Crema AS, et al. Permanent blue discoloration of a hydrogel intraocular lens by intraoperative trypan blue. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002;28:1279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fritz WL. Digital image analysis of trypan blue and fluorescein staining of anterior lens capsules and intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002;28:1034–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dada T, Ray M, Bhartiya P, et al. Trypan-blue-assisted capsulorhexis for trainee phacoemulsification surgeons. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002;28:575–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma N, Bhartiya P, Sinha R, et al. Trypan blue assisted phacoemulsification by residents in training. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2002;30:386–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yetik H, Devranoglu K, Ozkan S. Determining the lowest trypan blue concentration that satisfactorily stains the anterior capsule. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002;28:988–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]