Abstract

Tears have antimicrobial, nourishing, mechanical, and optical properties. They contain components such as growth factors, fibronectin, and vitamins to support proliferation, migration, and differentiation of the corneal and conjunctival epithelium. A lack of these epitheliotrophic factors—for example, in dry eye, can result in severe ocular surface disorders such as persistent epithelial defects. Recently, the use of autologous serum in the form of eye drops has been reported as a new treatment for severe ocular surface disorders. Serum eye drops may be produced as an unpreserved blood preparation. They are by nature non-allergenic and their biomechanical and biochemical properties are similar to normal tears. In vitro cell culture experiments showed that corneal epithelial cell morphology and function are better maintained by serum than by pharmaceutical tear substitutes. Clinical cohort studies have reported its successful use for severe dry eyes and persistent epithelial defects. However, the protocols to prepare and use autologous serum eye drops varied considerably between the studies. As this can result in different biochemical properties protocol variations may also influence the epitheliotrophic effect of the product. Before the definitive role of serum eye drops in the management of severe ocular surface disease can be established in a large randomised controlled trial this has to be evaluated in more detail. In view of legislative restrictions and based upon the literature reviewed here a preliminary standard operating procedure for the manufacture of serum eye drops is proposed.

Keywords: serum, blood products, ocular surface, dry eye, persistent epithelial defect, regulatory restrictions

Eye drops made from autologous serum are a new therapeutic approach for ocular surface disorders, such as persistent epithelial defects or severe dry eyes intractable to conventional therapy. Their use was first described by Fox et al in 1984 in their search for a tear substitute free of potentially harmful preservatives.1 Later Tsubota et al realised that because of the presence of growth factors and vitamins serum eye drops might also have a true epitheliotrophic potential for the ocular surface.2 Here, we review the theoretical background and the currently available literature on the use of this new approach and discuss some legislative implications.

Nutrition of the ocular surface

While the corneal demand for glucose, electrolytes, and amino acids is supplied by the aqueous humour, growth factors, vitamins and neuropeptides, which are secreted by the lacrimal gland, support proliferation, migration, and differentiation of the ocular surface epithelia.3–7 As part of inflammatory processes additional proteins such as the adhesion factor fibronectin, complement factors, and antimicrobial proteins (for example, lactoferrin, immunoglobulins) are released into the tears from conjunctival vessels.8,9 Tears thus have lubricating, mechanical, but also epitheliotrophic and antimicrobial properties. A reduction of epitheliotrophic factors or their carrier compromises, as in the gastrointestinal tract, the integrity of the surface epithelia. This can lead to epithelial defects, which as a result of compromised wound healing persist and progress. Surgical attempts to rehabilitate the ocular surface in severely dry eyes fail frequently.10,11 In this situation it is important to lubricate the ocular surface—however, the ideal tear substitute should, in addition, provide epitheliotrophic support.

The concept of natural tear substitutes

With few exceptions pharmaceutical products are optimised for their biomechanical properties only.12–14 Fibronectin, vitamins, and growth factors have been used in vitro and in vivo to encourage epithelial wound healing. However, owing to stability concerns and limited clinical success, such single compound approaches failed to become incorporated into routine clinical management.15–17 Serum and other bodily fluids have been used as natural tear substitutes. They are applied as unpreserved, autologous products and thus lack antigenicity.18,19 Serum is the fluid component of full blood that remains after clotting. It contains a large variety of growth factors, vitamins, and immunoglobulins, some in higher concentrations than in natural tears (table 1).2,16,20,20a These epitheliotrophic factors are thought to be responsible for the therapeutic effect of serum observed on ocular surface disorders.17,21–23 The growth and migration promoting effects of serum on cell cultures in general and on corneal epithelial cells are well documented.24,25 Fox was the first to use serum to treat human dry eyes. However, the recent renaissance of this therapy began when Tsubota in 1999 described its successful use in eyes with persistent epithelial defects.

Table 1.

| Tears | Serum | |

| pH | 7.4 | 7.4 |

| Osmolality (SD) | 298 (10) | 296 |

| EGF (ng/ml) | 0.2–3.0 | 0.5 |

| TGF-β (ng/ml) | 2–10 | 6–33 |

| Vitamin A (mg/ml) | 0.02 | 46 |

| Lysozyme (mg/ml) (SD) | 1.4 (0.2) | 6 |

| SIgA (μg/ml) (SD) | 1190 (904) | 2 |

| Fibronectin (μg/ml) | 21 | 205 |

EGF, epidermal growth factor; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; SIgA, surface immunoglobulin A.

Experimental studies

Tsubota was also the first to show that serum supports migration of an SV40 transfected human corneal epithelial cell line in a dose dependent manner25 and that immortalised, conjunctival epithelial cells as a sign of higher differentiation start to express mucin-1.2 In our own dose and time response experiments in a defined culture model, we found that serum maintained morphology and supported proliferation of primary human corneal epithelial cells far better than unpreserved or preserved pharmaceutical tear substitutes.24 Ebner et al recently also showed that incubation of primary cultures of human keratocytes with undiluted serum increased transcription of RNA for nerve growth factor (NGF) as well as TGF-β receptors.26

PREPARATION AND USE

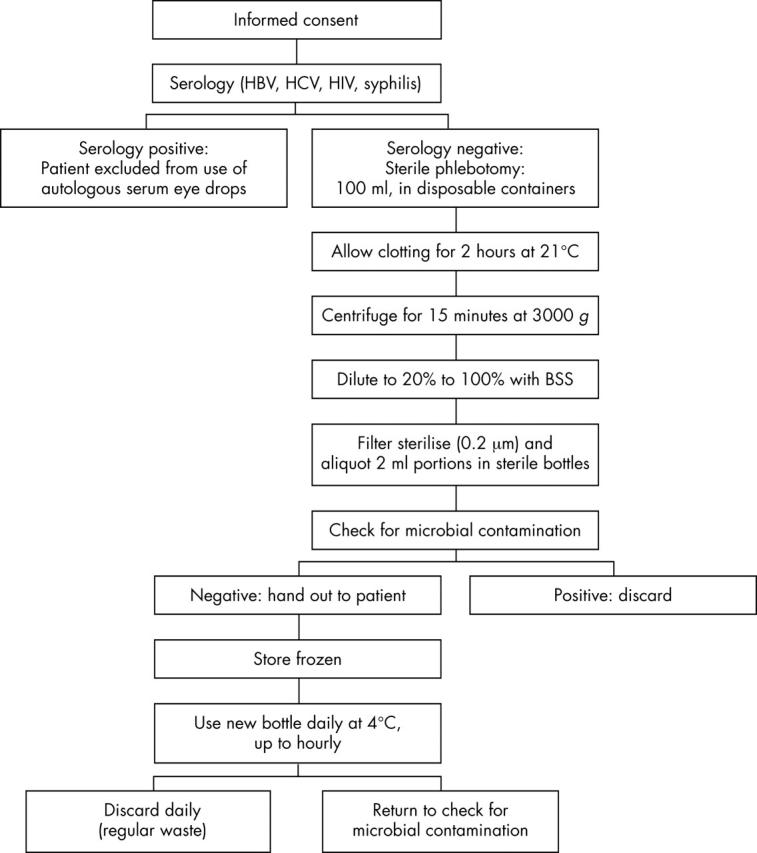

The protocols to produce serum eye drops in published reports are incomplete or vary significantly. Below we describe our current standard operating procedures (SOP) as well as published modifications (fig 1, table 2).

Figure 1.

Standard manufacturing protocol for the preparation, storage, and use of serum eye drops at the University of Lübeck, Germany.

Table 2.

Parameters that have to be defined in the production of serum eye drops and previously described variations, storage, and application

| Production factor | Published variations |

| Clotting phase | 0–2 days |

| Centrifugal force | 1500 rpm (ca 300 g) to 4000 g (ca 5000 rpm) |

| Duration of centrifugation | 5–20 minutes |

| Dilution | 20%, 33%, 50%, or 100% |

| Diluent | 0.9% NaCl, BSS, 0.5% chloramphenicol eye drops |

| Container | 1–6 ml in insulin syringe or dropper bottle |

| Storage | −20° to +4° C |

| Number of daily applications | 3 times to hourly |

rpm, rounds per minute; g, g force; BSS, balanced salt solution.

SOP at the University of Lübeck, Germany

Patients are assessed for their suitability to donate according to the guidelines of the Bundesärztekammer and Paul Ehrlich Institute for blood donation and use of blood products. This includes testing for hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV), syphilis, and HIV serology (HbsAg; antibodies to HCV, HIV-I/HIV-II, HIV-NAT, syphilis; HCV-NAT) before blood is donated for the production of eye drops. A positive serology excludes the patient from the use of autologous serum eye drops. Following a thorough information briefing regarding the experimental nature, potential complications, and alternative treatment options, informed consent is obtained. All steps are documented on a standard operation procedure form. Venesection is performed at the antecubital fossa under aseptic conditions and 100 ml of whole blood are collected into sterile containers.

The containers are left standing for 2 hours at room temperature in an upright position to ensure complete clotting before they are spun in a laboratory centrifuge at 3000 g for 15 minutes. The supernatant serum is removed under sterile conditions in a laminar air flow hood with sterile 50 ml disposable syringes. Following this protocol, 100 ml of whole blood will yield 30–35 ml of serum. The volume retrieved is determined, diluted 1:5 with sterile balanced salt solution (BSS), and filter sterilised (0.2 μm). Gentle shaking ensures homogenisation before portions of 2 ml are aliquoted into sterile dropper bottles. The bottles are sealed and labelled with the name, date of birth of the patient, the date of production, and the instruction “Autologous blood serum for topical use in the eye. To be stored frozen and used within 3 months after date of production; To be discarded at the end of the day.” A volume of 2 ml of the solution is—as required by the European Pharmacopoeia addendum 2000—sent for microbiological evaluation.

The product is available approximately 4 hours after venesection, but is only dispatched once negative serology and microbiology of donor and product are confirmed. Usually the drops are applied eight times daily. A new bottle is opened every day. It is recommended to be stored at +4°C and to be discarded after 16 hours of use with regular household waste. The remaining bottles are stored frozen (ideally at −20°C) for up to 3 months. If the domestic freezer has no thermometer it is recommended to place one inside and control the temperature when taking a new vial out every day. If the temperature can not be adjusted to about −20°C the dispensing doctor may consider recommendation of shorter storage episodes.

SOP of the National Blood Service in England and Wales

Following the principles of good manufacturing practice the National Blood Service (NBS) in England and Wales has chosen a different approach.27

Patients are assessed for their suitability to donate according to the British Committee for Standards in Haematology (BCSH) guidelines for pre-deposit autologous blood donation.28 This requires them to be in reasonably good health, with no significant cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, and free of bacterial infection. Anaemia (haemoglobin (Hb) <11 g/dl) is a relative contraindication.

Blood is collected following the same procedure as for all volunteer blood donors, except that donation is made into a sterile blood pack without anticoagulant. Those patients who are not thought suitable to donate a full unit of blood (470 ml) may have lesser amounts collected of 250–400 ml. Routine virology testing is performed as for volunteer blood donations in the United Kingdom (HBsAg, antibodies to HCV, HIV I/II, human T cell lymphoma virus (HTLV) and syphilis, HCV NAT).

The donation is stored at +4°C for 2 days to allow the blood to clot and the clot to retract fully. Serum is then separated from the clot of blood by centrifugation (a full donation yielding approximately 200 ml of serum), following which an equivalent volume of sterile normal saline is then added to the serum. The process up to this point is carried out in a “closed pack” system by utilising a sterile connecting device. The diluted serum is then transferred to a laminar flow cabinet in a positive air pressure clean room where 3 ml aliquots of serum are dispensed into sterile screw capped glass dropper bottles labelled with the patient’s details and storage instructions. Five bottles from each batch are sampled and undergo bacterial culture before release. The bottles are recapped and transferred to a blast freezer where the diluted serum is quickly frozen to a temperature of less than −30°C. The frozen serum is stored at this temperature, until collection by the patient, on dry ice in a sealed insulated cardboard box. One full donation produces approximately 150 bottles. Instructions are given to the patient about transferring the bottles to their home freezer. The shelf life of the product is stated as 6 months from the date of manufacture. Patients are instructed to use one bottle of serum per day, instilling at a frequency determined by symptoms (usually 3–6 times daily). Any remaining serum and the bottle are discarded at the end of the day.

Variations of production

While serum from various patients will certainly not be identical, it is also known that production factors significantly influence the biochemical properties of blood derived products (table 2). The effect of the centrifugation depends upon the centrifugal g force and time used to spin the sample. A centrifugation of 3000 g for 15 minutes results in good separation of serum and blood clot, without inducing haemolysis (fig 2).29 At a low g force or short centrifugation, platelet membranes remain in the supernatant and in high concentrations induce apoptosis.30 It is also important to understand that the g force not only depends upon the revolutions of the rotor per minute (rpm), but also on the diameter of the rotor. Thus, g force and not rpm should be stated in the protocol. The g force in the studies published so far, if mentioned at all, probably varies by at least 1 log.

Figure 2.

Demonstration of the influence of the g force on the volume of serum obtained from 50 ml of full blood centrifuged 2 hours after donation for 10 minutes at (left) 3000 (g) or (right) 500 (g). (Taken from Geerling et al, with permission of Springer Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany.)

We recently quantified EGF and TGF-β1 in undiluted serum samples of 10 patients and found a much lower concentration of TGF-β1 than Tsubota, who used a lower rpm—and thus probably a lower g force (table 3). As TGF-β potentially slows down epithelial wound healing, Tsubota suggested diluting the serum 1:5 with physiological saline. However, at the same time this reduces the concentration of other growth factors, such as EGF, that are proved to support proliferation of corneal epithelial cells.

Table 3.

Concentration of EGF and TGF-β1 for undiluted serum in pg/ml (SD) as analysed by a sandwich ELISA

| Centrifugation condition | EGF | TGF-β1 | |

| Geerling53 | 4000 g, 10 min | 802 (155) | 6029 (2517) |

| Tsubota2 | 1500 rpm, 5 min | 510 (80) | 33 200 (6800) |

Comparison of our data and results published by Tsubota (n = 10 each) illustrate the potential influence of g force on the composition of the product.

In addition, concentration and diluent in serum eye drops vary significantly. Daily dosage containers are predominantly used and discarded at the end of the day, but dilution with chloramphenicol 0.5% which has few toxic side effects has also been advocated to allow use of the dropper bottles for up to 1 week.31–33 Based on in vitro results we currently use 20% serum diluted in BSS.34

CLINICAL RESULTS

Serum eye drops have been used for severe dry eyes, persistent epithelial defects, and superior limbal keratoconjunctivitis as well as a supportive measure in ocular surface reconstruction. All published studies are listed in table 4.

Table 4.

Production conditions and results of studies published. Success is defined either as number of all eyes/patients improving or as reduction of mean baseline (as stated in the paper) of fluorescein, rose bengal positive epitheliopathy (objective), or symptoms (subjective) score

| Author | Year | Concentration/diluent | Centrifugation (g force/duration) | Clotting time | Frequency/remarks | Indication | Eyes (patients) | Success objective | Success subjective |

| Fox1 | 1984 | 33%/0.9% NaCl | 500 g/10 min | NR | 2 hourly | KCS | 30 (15) | RB 41% | 51%; 15 (15) |

| Tsubota2 | 1999 | 20%/NaCl | 1500 rpm/5 min | NR | 6–10× | KCS in SS | 24 (12) | Fl: 55 %; RB: 68% | 34 % |

| Rocha35 | 2000 | 33%/0.9% NaCl | 500 g/10 min | NR | Hourly, filtered | KCS in GVHD | 4 (2) | 4 (4) | 4 (4) |

| Poon33 | 2001 | 50–100%/0.5% chloramphenicol | 4000 rpm (2200 g)/10 min | 2 h | 8× | KCS | 11 (9) | Fl: 6 (11) BR: 5 (11) | 6 (11) |

| Tananuvat38 | 2001 | 20%/0.9% NaCl | 4200 rpm/15 min | NR | 6× | KCS | 12 (12) | Fl: 39%; RB: 33% IPC 44% | 36% (NS) |

| Takamura37 | 2002 | 20%/0.9% NaCl | 3000 rpm/10 min | NR | 4–8× | KCS | NR (26) | “improved” | 20 (26) |

| Ogawa36 | 2003 | 20%/0.9% NaCl | 1500 rpm/5 min | NR | 10× | KCS in GVHD | 28 (14) | Fl: 61%, RB 40% | 30 % |

| McDonnell47 | 1988 | 100% | NC/15–20 min | 15 min | 1–2 hourly | PED | 1 (1) | IC deposition | No |

| Tsubota25 | 1999 | 20%/NaCl | 1500 rpm/5 min | NR | 6–10× | PED | 16 (15) | 10 (16) | NR |

| Poon33 | 2001 | 50–100%/0.5% chloramphenicol | 4000 rpm (2200 g)/10 min | 2 h | 8× | PED | 15 (13) | 9 (15) | NR |

| De Souza42 | 2001 | 100% | NC | NR | Hourly | PED/PK | 70 (63) | 57 (70) | NR |

| Garcia43 | 2003 | 20%/0.9% NaCl | 5000 rpm/10 min | NR | 10× | PED | 11 (11) | 6 (11) | NR |

| Tsubota45 | 1996 | 20%/NaCl | 1500 rpm/5 min | NR | ¼ hourly | LSC-Tx, PK | 14 (11) | 12 (14) | NR |

| Poon33 | 2001 | 50–100%/0.5% chloramphenicol | 4000 rpm (2200 g)/10 min | 2 h | 8× | PK | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | NR |

| Del Castillo41 | 2002 | 20%/0.9% NaCl | 1500 rpm/5 min | NR | 3× | RES | 11 (11) | 8 (11); RoR: 99% | NR |

| Goto40 | 2001 | 20%/0.9% NaCl | 1500 rpm/5 min | NR | 10× | SLK | 22 (11) | Fl 88%, BR 91% IPC 100% | 21%, 9 (11) |

| Noble39 | 2003 | 50%/0.9% NaCl | NR | 48–72 h | Replacement | OSD | 32 (16) | IPC 9 (25) | 10 (16) |

| Matsumoto20a | 2004 | 20%/NaCl | 3000 rpm/10 min | NR | 5–10× | NK | 14 (11) | 14 (14) | NR |

Note that the scale used to measure these changes as well as the baseline level varied between the studies. GvHD, graft versus host disease; IC, immune complex; IPC, impression cytology; KCS, keratoconjunctivitis sicca; LSCTX, limbal stem cell transplautation; NK, neurotrophic keratopathy; NR, not reported; NS, not significant; OS, ocular surface; OSD, ocular surface disease; PED, persistent epithelial defect; PK, penetrating keratoplasty; Replacement, frequency equivalent to previously applied pharmaceutical tear substitute; RoR, rate of recurrence; SLK, superior limbal keratoconjunctivitis; SS, Sjögren’s syndrome.

Severe dry eye and superior limbal keratoconjunctivitis

In 1984 Fox et al reported that a 3 week course with serum diluted 1:2 with 0.9% NaCl solution was able to improve the signs and symptoms in 30 eyes of 15 patients.1 When this medication was replaced by serum diluted 1:200 or pure diluent the discomfort increased again. Fifteen years later Tsubota et al reported that symptoms, fluorescein, and rose bengal staining of dry eyes in Sjögren’s syndrome were significantly decreased after 4 weeks of 20% serum eye drops 6–10 times daily.2 Similar findings were described in patients with dry eye because of graft versus host disease,35,36 with symptoms improving within days, but punctate epithelial staining improving only after months. In 14 patients with moderate keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) in graft versus host disease (GvHD) (Schirmer test <10 mm) the improvement lasted more than 6 months, but six patients required additional punctal occlusion. In a prospective study by Poon et al an improvement of subjective and objective criteria of severe dry eyes (Schirmer test <5 mm). was found in all eyes receiving 100% serum (n = 3), but only in three out of eight eyes on 50% serum.33 The efficacy may be dose dependent since in a study by Takamura 94% of patients receiving eight applications reported reduced symptoms compared to only 58% of those receiving four drops.37

However, in a placebo controlled prospective study in severe dry eye 20% serum six times daily was not able to improve discomfort or objective signs significantly better than the diluent 0.9% saline.38 Since fluorescein and rose bengal staining tended to be reduced after 2 months of treatment, the authors concluded that a larger controlled study was required. Noble et al compared the efficacy of 3 months of autologous serum 50% diluted in physiological saline in a prospective clinical crossover trial as a substitute for the conventional therapy already used by each patient.39 Ten out of 16 patients improved. Impression cytology showed improvement in nine, no change in 10, and deterioration in six of treated 25 eyes.

Superior limbal keratoconjunctivitis (SLK), a rare, chronic, inflammatory disease with rose bengal staining of the corneal and conjunctival epithelium at the 12:00 limbus is thought to result from a localised tear film deficiency. In a prospective cohort study 20% serum eye drops were used as additional therapy 10 times daily for bilateral SLK. Within 4 weeks discomfort improved in nine of 11 and epitheliopathy in all patients. Tear break up time increased significantly and conjunctival squamous metaplasia was reduced. When the serum application was discontinued, discomfort increased again.40

Overall, the efficacy of serum drop therapy varies between 30–100% for symptomatic relief, 39–61% for reduction of fluorescein, and 33–68% for rose bengal positive epitheliopathy. These discrepancies may result from variations in the study populations—that is, the degree of aqueous deficiency, as well as from variations in the production and treatment protocol for serum eye drops. In some, serum was used as an additive rather than a substitute treatment and in others therapeutic contact lenses or punctal occlusion were applied with initiation of serum eye drops. Increasing fluid supply rather than the epitheliotrophic nature of serum may thus have yielded the beneficial effect. Comparison of the published data is further limited by variations in reporting “success of treatment” as (a) number of patients improving or (b) mean change of a parameter.

Recurrent erosion syndrome

Recurrent erosion syndrome (RES) is a frequent complication of trauma or corneal basement membrane dystrophy leading to repeated episodes of irritation, pain, epiphora, and hyperaemia because of insufficient adhesion of the basal epithelial layers to the underlying basement membrane. In a prospective cohort study 11 patients with unilateral post-traumatic RES used unspecified unpreserved pharmaceutical tears and 20% serum eye drops three times daily for 3 months in a tapered fashion. No comment is made as to whether previously used alternative treatments were suspended for the time of the serum application. Mean recurrence rate was reduced from 2.2 to 0.028/month of follow up (mean follow up 9.4 (SD 3.7) months). However, given the self healing nature of post-traumatic RES and the fact that the duration since trauma was not specified these data have to be viewed with care.41

Persistent epithelial defects

Persistent epithelial defect (PED) can result from rheumatoid arthritis, neurotrophic keratopathy, or dry eye.42 Tsubota in 1999 and later Garcia-Jimenez reported the use of 20% serum in a prospective case series. Many patients also suffered from an aqueous deficient dry eye or corneal hypaesthesia. The PEDs had persisted despite treatment with lubricants or bandage contact lenses for more than 2 weeks (mean 7.2 (SD 9.4) months). Ten out of 16 defects healed completely within 4 weeks of initiation of therapy. Wound closure tended to correlate negatively with the duration of the defect before therapy with serum.25,43 Poon used 50–100% serum eye drops as a substitute for unpreserved pharmaceutical lubricants. In nine of 15 eyes that had had a PED for 7.5 (SD 5.8) (range 1–24) weeks healing started within 2 weeks and was completed after 3.6 (SD 2.5) weeks (range 3 days–8 weeks). However, six out of the nine defects recurred when serum eye drops were changed back to pharmaceutical lubricants.33

In a prospective study De Souza treated 70 epithelial defects (63 patients) with undiluted serum hourly in addition to routine medication; 45 of these defects had occurred early after penetrating keratoplasty.42 With a mean time of 15 (SD 17) days, the history of PED was short; 57 defects healed within 14 (12) days, but nine (16%) recurred within 2 months when serum drops were stopped. Total mean follow up was 12 (4) months. Neither size nor localisation of the defect correlated significantly with success or failure, but deeper defects showed a tendency to heal less successfully. None of these studies however was placebo controlled.

Meanwhile, umbilical cord serum has been advocated as an alternative treatment for promoting corneal epithelial wound healing. In a prospective randomised controlled clinical trial on 60 eyes this led to faster healing of PEDs refractory to all medical management compared to autologous serum. While all considerations regarding the preparation, quality control, and legal implications are also valid for this option, additional difficulties may be associated with obtaining and using this allogenic blood preparation.44

Adjunctive treatment in ocular surface reconstruction

Surgical attempts to rehabilitate severe ocular surface disease (OSD) in absolute aqueous deficiency frequently fail. In a prospective cohort study, 14 eyes of 11 patients who had received a limbal stem cell graft, amniotic membrane, and/or penetrating keratoplasty were treated with 20% serum eye drops. Because of Stevens-Johnson syndrome or ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, all eyes had Schirmer test results of 0 mm with nasal stimulation. During the short follow up of 20 weeks, 12 of the 14 reconstructions resulted in a stable corneal epithelium.45 Poon confirmed this in two eyes undergoing keratoplasty for PEDs, but epitheliopathy recurred when the treatment was discontinued. However, in young patients with severe OSD and absolute dry eye surface reconstruction failed despite the use of autologous serum eye drops.46

Complications

The number of complications in the 255 patients reported to have been treated with serum eye drops is small. Most authors report no complications at all. Fox et al reported no serious complications,1 but mentioned that other users had encountered scleral vasculitis and melting in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Immune complex deposition after hourly application of 100% serum and one peripheral corneal infiltrate and ulcer within 24 hours after initiation of serum drops have been reported.33,47 Circulating antibodies which are present in serum eye drops and antibodies in the cornea could theoretically form such immune complex deposits in the peripheral cornea and induce an inflammatory response. In five patients with dry eyes, discomfort or epitheliopathy increased with the use of serum eye drops and three patients with an epithelial defect developed a microbial keratitis. A temporary bacterial conjunctivitis was reported in a total of five cases and eyelid eczema in two.35,36,38 However, these complications could also have occurred in the natural course of the disease because of other risk factors such as presence of rheumatoid arthritis, remaining suture material, tear deficiency, and use of bandage contact lenses.

PROBLEMS, LEGAL ASPECTS, QUALITY CONTROL, AND COSTS

Potential disadvantages of serum eye drops are the limited stability and the risk of infection arising for patients and others handling serum. Published evidence on these issues is scanty.

Stability

Tsubota et al reported that the concentration of growth factors, vitamin A, and fibronectin in 100% and 20% serum diluted with NaCl stored at 4°C remained unchanged for 1 month and at −20°C for at least 3 months.2 As with other bodily fluids it should be expected that at 4°C protein concentrations decrease significantly in the course of weeks. Since in developed countries access to freezers is rarely a problem it therefore seems preferable to store unused vials of serum frozen to optimally preserve the activity of epitheliotrophic factors.48 However no more detailed published evidence is available to clarify the minimum freezer temperature required for several months of storage.

Risk of infection

One of the disadvantages of autologous serum eye drops is the risk of inducing an infection because of, for example, hepatitis of the donor or microbial contamination of the initially sterile dropper bottle during prolonged use. This may occur during preparation as well as application of the drops either to the correct or any accidental recipient. Transmission of HIV by a single serum droplet into one eye has been reported at least in one case.49

Although serum is known to have antimicrobial properties, so far this has not been quantified for diluted cryopreserved serum. When used in a hospital setting and applied by trained personnel no contamination was observed in week dosage dropper bottles until the fourth day.50 However, when the drops were used in a domestic setting by the patients themselves microbial keratitis evolved in three out of 13 eyes with PEDs treated with serum and contamination of dropper bottles was observed despite using 0.5% chloramphenicol as a preservative.33 Since laboratory evidence suggests that dilution with an antibiotic may reduce the epitheliotrophic capacity of serum eye drops and ocular surface disease often requires long term treatment, hospitalisation of patients for this purpose is not a suitable option and storage of the serum product in day dosage vials seems preferable.

Standardising the production of serum eye drops

Neither production, nor application (that is, frequency) of serum have been standardised so far. It also remains unclear whether the serum should be filter sterilised to remove any corpuscular blood components. Fox recommends filtration to remove fibrin strands, suspected to reduce the effect of serum eye drops. The variable efficacy of serum eye drops suggests that the parameters for their production should be standardised and optimised before any meaningful placebo controlled randomised clinical trial can evaluate the real potential of this new therapy.34

Legal aspects

Autologous serum eye drops are a medical product. The distribution of pharmaceutical products is regulated by governmental laws in most countries. In the European Union (EU), the manufacture and distribution of pharmaceuticals are regulated by the individual country; however, several directives have been issued (1965/65, 1975/139, 1975/318) by the European parliament and council. These directives had to be taken into account in the laws of each member state of the EU and led to the implementation of a marketing authorisation to be issued by a competent authority of each state. The marketing authorisation depends on the proof of efficacy in clinical trials, implementation of quality controls, reports of adverse effects, proof of expert knowledge, and other regulatory aspects. These criteria can, in most cases, probably only be fulfilled by professional pharmaceutical manufacturers.

An exemption from the need to obtain marketing authorisation is granted, if a physician manufactures or prescribes a specific medical product to treat his own patient on a named basis. This product has to be prepared according to the doctor’s specifications, whose responsibility it remains that manufacture and application are performed correctly. Autologous serum eye drops can therefore be produced by the physician himself or on his prescription. Since stricter regulations, especially for blood products, may exist in individual states every physician producing or prescribing autologous serum eye drops has to appraise himself about specific national regulations.

In England and Wales the NBS has supplied autologous serum eye drops so far under a drug exemption certificate for the purposes of a clinical trial from the regulatory body in the United Kingdom, the Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency (MHRA).39 The NBS hopes to be able to offer this therapy nationally in the near future, following inspection of the procedure by the MHRA. At this stage the treatment will continue to be monitored by the MHRA who will receive annual safety reports.

In the United States, producers of drugs and medical devices have to be registered with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Similar to EU regulations, registration is not necessary “for practitioners licensed by law to prescribe or administer drugs or devices and who manufacture, prepare, propagate, compound, or process drugs or devices solely for use in the course of their professional practice.” Again, special regulations on testing and approval of drugs by the FDA or for using blood products have to be evaluated by the practitioner.

Quality control and patient information

Before application, the patient must be informed in writing about the planned therapy, its experimental nature, the risks involved (for example, bacterial contamination), and alternative methods of treatment. The patient’s informed consent should be obtained. If only a small amount of blood (50–100 ml) is taken mild anaemia or circulatory disorders need not be considered as contraindications. However, in order to minimise the danger of bacterial contamination, no blood should be taken from patients with suspected septicaemia, and to reduce the risk of viral transmission to others, patients testing positive for HIV, HBV, HCV, or syphilis should be excluded.

Bacterial contamination is a potential risk in the production and use of serum eye drops. Sterile manufacturing conditions, beginning with thorough skin disinfection, are of the utmost importance. It is preferable that further processing is performed in a closed system. A microbiological examination of the product should be performed before application in order to rule out bacterial contamination resulting from the production process. To minimise the risk of infection to third parties (for example, production or nursing staff) it is strongly recommended that the donor is tested for HIV, HBV, and HCV and a control system must be implemented to ensure that the product is only used when the microbiological and serological tests are clear.

Before venesection and application, the identity of the patient must be confirmed. The packaging must be clearly labelled with the patient’s name, date of birth, a comment that the material is an autologous blood product, which is solely for application to the patient named, as well as the name and address of the manufacturer and the date of manufacture.

To minimise the variability of the product and to maximise the safety of its use, a written version of the standard production procedures should be established. Conscientious documentation is indispensable for good medical and manufacturing practice. Each step relevant to manufacture as well as application (including the dates of application and any unwanted effect) should be recorded. From this it becomes obvious that strict guidelines for good manufacturing, quality control and documentation must be established and maintained before and throughout the therapeutic use of autologous serum eye drops.

Costs

As the production of serum eye drops from autologous blood is time consuming and labour intensive the costs of this approach have to be considered. Table 5 shows the costs for the production of serum eye drops for the pharmacy department of the University of Lübeck for the year 2003. When excluding the costs for the acquisition of the necessary laboratory hardware (for example, laminar air flow hood, centrifuge) the total costs of a day dosage is €2.27 for 20% and €4.61 for 100% serum eye drops. This is approximately equivalent to the costs of one bottle of preserved pharmaceutical lubricant. Since serum eye drops are reserved for cases of OSD refractive to other forms of treatment, resulting in severe discomfort and/or considerable economic costs to society, this sum seems to be acceptable.

Table 5.

Costs of production for 20% and 100% serum eye drops produced out of 100 ml full blood and filled as 2 ml aliquots in sterile dropper bottles (calculation based on figures of the Department of Pharmacy of the University Hospital Lübeck for the year 2003)

| Costs (€) | ||

| For 100% serum eye drops | For 20% serum eye drops | |

| Average number of bottles | 15 | 75 |

| Disposable materials/substances | ||

| Gauze, cannula, gloves (2×) | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Serum vacuum container (€0.08 each) | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| 6 BSS ampoules (10 ml, €4.5 each) | – | 27.00 |

| Dropper bottle (€0.80 each) | 12.00 | 60.00 |

| Labels (€0.02 each) | 0.30 | 1.50 |

| Box for transportation | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Personnel/production | ||

| Doctor (€40/h) | 10.00 | 10.00 |

| Pharmaceutical production assistant (€25/h) | 25.00 | 50.00 |

| Transportation | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Serological examinations | 13.00 | 13.00 |

| Total costs | 69.20 | 170.40 |

| Costs/bottle | 4.61 | 2.27 |

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

While pharmaceutical lubricants offer little to no nutrition eye drops made from autologous serum have a tear-like biochemical character and supply nutritional components. In vitro studies have shown that serum supports viability, proliferation and migration of ocular surface epithelial cells better than unpreserved pharmaceutical tear substitutes. Clinical studies described a variable efficacy of serum eye drops in, for example, PEDs and dry eyes refractive to conventional treatment. This in part can be attributed to variations in the manufacturing protocol of serum eye drops. The production parameters should be optimised before a meaningful randomised, controlled clinical trial attempts to evaluate the real therapeutic potential of this approach in OSD. Meanwhile, the use of serum eye drops remains an experimental approach. Therefore, all applicable legislative restrictions should be carefully considered and well documented and informed consent should be obtained from each patient.

Acknowledgments

This work was in parts funded by a research grant from the University of Lübeck.

The authors thank the head pharmacist of the University Hospital Schleswig Holstein, H G Strobel, for calculating the costs of production of serum eye drops.

Abbreviations

BSS, balanced salt solution

EGF, epidermal growth factor

GvHD, graft versus host disease

Hb, haemoglobin

HBV, hepatitis B virus

HCV, hepatitis C virus

HTLV, human T cell lymphoma virus

KCS, keratoconjunctivitis sicca

OSD, ocular surface disease

PED, persistent epithelial defect

RES, recurrent erosion syndrome

rpm, rounds per minute

SLK, superior limbal keratoconjunctivitis

SOP, standard operating procedures

TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta

REFERENCES

- 1.Fox RI, Chan R, Michelson JB, et al. Beneficial effect of artificial tears made with autologous serum in patients with keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:459–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsubota K , Goto E, Fujita H, et al. Treatment of dry eye by autologous serum application in Sjögren’s syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol 1999;83:390–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson SE, Linag Q, Kim WJ. Lacrimal gland HGF, KGF and EGF mRNA levels increase after corneal epithelial wounding. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999;40:2185–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton K , Nava A, Monroy DC, et al. Cytokines and tear function in ocular surface disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 1998;438:461–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fredj-Reygrobellet D , Plouet J, Delazre T, et al. Effects of aFGF and bFGF on wound healing in rabbit corneas. Curr Eye Res 1987;6:1205–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pastor JC, Calonge M. Epidermal growth factor and corneal wound healing: a multicenter study. Cornea 1992;11:311–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scardovi C , De Felice GP, Gazzaniga A. Epidermal growth factor in the topical treatment of traumatic corneal ulcers. Ophthalmologica 1993;206:119–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuda M , Fullard RJ, Willcox MD, et al. Fibronectin in the tear film. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1996;37:459–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiffany J . Tears and conjunctiva. In: Harding JJ, ed. Biochemistry of the eye. London: Chapman and Hall Medical, 1997:1–15.

- 10.Kao WWY, Kao CWC, Kaufman AH, et al. Healing of corneal epithelial defects in plasminogen- and fibrinogen-deficient mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1998;39:502–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiou AG, Florakis GJ, Kazim M. Management of conjunctival cicatrizing diseases and severe ocular surface dysfunction. Surv Ophthalmol 1998;43:19–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yokoi N , Komuro A, Nishida K, et al. Effectiveness of hyaluronan on corneal epithelial barrier function in dry eye [see comments]. Br J Ophthalmol 1997;81:533–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ubels J , Williams K, Lopez Bernal D, et al. Evaluation of effects of a physiologic artificial tear on the corneal epithelial barrier: electrical resistance and carboxyfluorescein permeability. In: Sullivan DA, ed. Lacrimal gland, tear film and dry eye syndromes. New York: Plenum Press, 1994:441–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Nelson JD, Drake MM, Brewer JTJ, et al. Evaluation of a physiological tear substitute in patients with keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Adv Exp Med Biol 1994;350:453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez Bernal D , Ubels JL. Artificial tear composition and promotion of recovery of the damaged corneal epithelium. Cornea 1993;12:115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson JD, Gordon JF. Topical fibronectin in the treatment of keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Chiron Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca Study Group. Am J Ophthalmol 1992;114:441–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon JF, Johnson P, Musch DC. Topical fibronectin ophthalmic solution in the treatment of persistent defects of the corneal epithelium. Am J Ophthalmol 1995;119:281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geerling G , Sieg P, Bastian GO, et al. Transplantation of the autologous submandibular gland for most severe cases of keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Ophthalmology 1998;105:327–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaumeil C , Liotet S, Kogbe O. Treatment of severe eye dryness and problematic eye lesions with enriched bovine colostrum lactoserum. In: Sullivan DA, ed. Lacrimal gland, tear film and dry eye syndromes—basic science and clinical relevance. New York, London: Plenum Press, 1994:595–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Joh T , Itoh M, Katsumi K, et al. Physiological concentrations of human epidermal growth factor in biological fluids: use of a sensitive enzyme immunoassay. Clin Chim Acta 1986;158:81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a.Matsumoto Y , Dogou M, Goto E, et al. Autologousserum application in the treatment of reurotrophic keratopathy. Ophthalmology 2004;111:1115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCluskey P , Wakefield D, York L. Topical fibronectin therapy in persistent corneal ulceration. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1987;15:257–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishida T , Ohasai Y, Awata T, et al. Fibronectin a new therapy for corneal trophic ulcer. Arch Ophthalmol 1983;101:1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phan TM, Foster CE, Bourochoff SA, et al. Topical fibronectin in the treatment of persistent corneal epithelial defects and trophic ulcers. Am J Ophthalmol 1987;104:494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geerling G , Daniels JT, Dart JK, et al. Toxicity of natural tear substitutes in a fully defined culture model of human corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001;42:948–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsubota K , Goto E, Shimmura S, et al. Treatment of persistent corneal epithelial defect by autologous serum application. Ophthalmology 1999;106:1984–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ebner S , You L, Voelcker HE, et al. Effect of autologous serum on the healing of non-infectious corneal ulcers and expression of growth factor receptors in the cornea. Ophthalmologe 2001;98:S27. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stationery Office. Rules and guidance for pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors 2002 incorporating—EC guide to good manufacturing practice and good distribution practice—EC directives on manufacturing, wholesale distribution and good manufacturing practice. London: Stationery Office, 2002.

- 28.Voak D , Finney RD, Forman K, et al. Guidelines for autologous transfusion and pre-operative autologous donation, British Committee for Standards in Haematology Blood Transfusion Task Force. Transfusion Med 1993;3:307–16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas L . Labor und Diagnose. 5. Auflage ed: TH-Books, 1998:1494.

- 30.Dugrillon A , Lauber S, Nguyen XD, et al. Platelets applied to wounds and in tissue regeneration: induction of proliferation apoptosis by platelet membranes. In: Mempel W, Schramm W, eds. Infusion therapy and transfusion medicine 2002:70–1.

- 31.Nakamura M , Nishida T, Mishima H, et al. Effects of antimicrobials on corneal epithelial migration. Curr Eye Res 1993;12:733–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berry M , Gurung A, Easty DL. Toxicity of antibiotics and antifungals on cultured human corneal cells: effect of mixing, exposure and concentration. Eye 1995;9:110–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poon AC, Geerling G, Dart JK, et al. Autologous serum eyedrops for dry eyes and epithelial defects: clinical and in vitro toxicity studies. Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:1188–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herminghaus P , Hartwig D, Wedel T, et al. Epitheliotrophe Kapazität von Serum- und Plasma-Augentropfen—Einfluss der Zentrifugation. Ophthalmologe 2004;101 (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Rocha EM, Pelegrino FS, de Paiva CS, et al. GVHD dry eyes treated with autologous serum tears. Bone Marrow Transplant 2000;25:1101–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogawa Y , Okamoto S, Mori T, et al. Autologous serum eye drops for the treatment of severe dry eye in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant 2003;31:579–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takamura E , Shiozaki K, Hata H, et al. Efficacy of autologous serum treatment in patients with severe dry eye. In: Sullivan DA, ed. Lacrimal gland, tear film, and dry eye syndromes 3. Amsterdam: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2002:1247–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Tananuvat N , Daniell M, Sullivan LJ, et al. Controlled study of the use of autologous serum in dry eye patients. Cornea 2001;20:802–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noble BK, Loh RS, MacLennan S, et al. Comparison of autologous serum eye drops with conventional therapy in a randomised controlled crossover trial for ocular surface disease. Br J Ophthalmol 2004;88:603–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goto E , Shimmura S, Shimazaki J, et al. Treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis by application of autologous serum. Cornea 2001;20:807–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Del Castillo JM, de la Casa JM, Sardina RC, et al. Treatment of recurrent corneal erosions using autologous serum. Cornea 2002;21:781–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferreira de Souza R , Kruse FE, Seitz B. [Autologous serum for otherwise therapy resistant corneal epithelial defects—prospective report on the first 70 eyes]. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 2001;218:720–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia-Jimenez V , Veiga Villaverde B, Baamonde Arbaiza B, et al. [The elaboration, use and evaluation of eye-drops with autologous serum in corneal lesions]. Farm Hosp 2003;27:21–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vajpayee RB, Mukerji N, Tandon R, et al. Evaluation of umbilical cord serum therapy for persistent corneal epithelial defects. Br J Ophthalmol 2003;87:1312–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsubota K , Satake Y, Ohyama M, et al. Surgical reconstruction of the ocular surface in advanced ocular cicatricial pemphigoid and Stevens-Johnson syndrome [see comments]. Am J Ophthalmol 1996;122:38–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsubota K , Shimazaki J. Surgical treatment of children blinded by Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1999;128:573–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McDonnell PJ, Schanzlin DJ, Rao NA. Immunoglobulin deposition in the cornea after application of autologous serum. Arch Ophthalmol 1988;106:1423–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sitaramamma T , Shivaji S, Rao GN. Effect of storage on protein concentration of tear samples. Curr Eye Res 1998;17:1027–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eberle J , Habermann J, Gurtler LG. HIV-1 infection transmitted by serum droplets into the eye: a case report. AIDS 2000;14:206–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sauer R , Bluthner K, Seitz B. [Sterility of non-preserved autologous serum drops for treatment of persistent corneal epithelial defects]. Ophthalmologe 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Ciba-Geigy. Wissenschaftliche Tabellen Geigy. Basel: Ciba-Geigy, 1978.

- 52.Geerling G , Honnicke K, Schroder C, et al. Quality of salivary tears following autologous submandibular gland transplantation for severe dry eye. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1999;237:546–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Geerling G , et al. Der Ophthalmologe. Autologe Serum-Augentopfen zur Therapie der Augenoberfläche—Eine Übersicht zur Wirksamkeit und Empfehlungen zur Anwendung 2002;99:949–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]