Abstract

Aim: To compare the effectiveness of three models of low vision rehabilitation for people with age related macular degeneration (AMD) referred for low vision rehabilitation (LVR): (a) an enhanced low vision rehabilitation model (ELVR) including supplementary home based low vision rehabilitation; (b) conventional low vision rehabilitation (CLVR) based in a hospital clinic; (c) CLVR with home visits that did not include rehabilitation (CELVR), intended to act as a control for the additional contact time with ELVR.

Method: A single centre parallel group randomised controlled trial in participants’ homes and the low vision clinic, Manchester Royal Eye Hospital. People referred for LVR with a primary diagnosis of AMD and visual acuity worse than 6/18 in both eyes and equal to or better than 1/60 in the better eye. The main outcome measures were vision specific quality of life (QoL) (primary outcome, VCM1) and generic health related QoL (SF-36); psychological adjustment to vision loss; measured task performance; restriction in everyday activities; use of low vision aids (LVAs).

Results: 226 participants were recruited (median age 82 years); 194 completed the trial (86%). Except for SF-36 physical and mental component summary scores, arms did not differ significantly for any of the outcomes. Differences for the VCM1 were ELVR v CLVR, 0.06 (95% CI to 0.17 to 0.30, p = 0.60); ELVR v CELVR, 0.12 (95% CI to 0.11 to 0.34, p = 0.31); CELVR v CLVR, –0.05 (95% CI –0.29 to 0.18, p = 0.64). Differences for the SF-36 favoured CLVR compared to ELVR (ELVR v CLVR: physical = –6.05, 95% CI –10.2 to –1.91, p = 0.004; mental = –4.04, 95% CI –7.44 to –0.65, p = 0.02). At 12 months, 94% of participants reported using at least one LVA.

Conclusion: ELVR was no more effective than CLVR. Researchers should be wary of proposing new LVR interventions without preliminary evidence of effectiveness, given the manifest lack of effectiveness of the model of enhanced LVR evaluated in the trial.

Keywords: low vision services, age related macular degeneration, randomised controlled trial

Age related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of visual impairment in the Western world1,2 and represents a substantial and growing healthcare burden. AMD causes a number of impairments including deteriorating visual acuity, central visual field sensitivity, and contrast sensitivity. These impairments usually cause significant disability,3 with difficulties with reading, everyday activities of daily living, watching television, all of which may impact on quality of life.4,5 Despite some advances, the medical treatment options for AMD have important limitations6–8 and patients with AMD are usually referred for low vision rehabilitation (LVR). LVR includes a range of services for people with low vision with the aim of minimising disability by helping them to make best use of their remaining eyesight.9

In the United Kingdom, conventional LVR is mainly provided by optometrists working in the hospital eye service (HES).10 It is primarily focused on minimising limitations in activities by providing low vision aids (LVAs), usually magnifiers, and teaching people about the importance of controlling illumination. A recent national survey in the United Kingdom highlighted several problems with low vision services including fragmentation of services; lack of multidisciplinary or “integrated” care incorporating input from a range of professionals (for example, optometrists, ophthalmologists, low vision rehabilitation officers, and social workers); inadequate communication between service providers.11

There is a lack of systematic research about the effectiveness of LVR. Previous studies of rehabilitation for people with AMD have been retrospective or prospective case series,12–16 except for two small controlled trials of rehabilitation training17,18 and one small trial of the specific intervention of prism relocation spectacles.19 These studies have tended to use non-standardised outcomes including patient satisfaction questionnaires and reported use of LVAs. Many of the studies have suggested that a lack of training in the use of LVAs is a fundamental reason for the limited effectiveness of the service provided; Shuttleworth and colleagues argued that a more integrated service with enhanced training in the use of LVAs is more effective than conventional LVR.14

The present trial measured the effectiveness of different strategies of low vision rehabilitation for subjects with newly diagnosed AMD.20 We hypothesised that patients with AMD who received conventional LVR with supplementary home based rehabilitation would have better quality of life (QoL) and be better able to carry out everyday activities than patients who received conventional LVR.

METHODS AND PARTICIPANTS

Study design

The study was a three arm randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing (a) conventional LVR (CLVR) as provided by the HES, (b) conventional LVR “enhanced” by home visits from a rehabilitation officer for the visually impaired (ELVR), and (c) conventional LVR supplemented by home visits from a community care worker. The latter arm was intended to act as a control for the contact time with subjects allocated to ELVR (hence CELVR). The study was approved by the central research ethics committee of Manchester Health Authority (reference CM/96/108).

Allocation was randomised and blocked using blocks of unequal length. Allocation codes were generated by computer before the start of the study by BCR (who took no part in recruitment, data collection, or the care of patients) and were concealed in sealed opaque envelopes. Eligible people were told about the study and were invited to participate by a large print letter. Those who agreed to participate gave written informed consent. At recruitment, an appointment was made for the initial home visit. RAH then randomised the participant by opening the next sealed envelope, keeping the allocation secret from the researcher who measured outcomes (WBR).

Participants

People were eligible for the trial if they were newly referred to the low vision clinic at Manchester Royal Eye Hospital with a primary diagnosis of AMD. Potential participants had to have Snellen visual acuity worse than 6/18 (>0.5 logMAR) in both eyes and equal to or better than 1/60 (⩽1.8 logMAR) in the “better” eye. People were ineligible if they were living in a residential or nursing home, were suffering from mental illness or dementia, or were not proficient in English.

Interventions

The components of the different models of LVR are summarised in table 1. Participants allocated to CLVR received a clinical low vision assessment at the hospital provided by a team of qualified optometrists, a dispensing optician, and a limited number of preregistration optometrists working under supervision. As a pragmatic trial, assessments were carried out as part of standard hospital care for people referred to the low vision clinic. While general guidelines were suggested (as summarised in table 1), practitioners did not have to adhere to a strict assessment protocol, although they were asked to complete data sheets requesting information on diagnosis, co-morbidity, visual requirements, unaided vision, performance with existing LVAs (if any), refraction, corrected acuities, contrast sensitivity, and performance with new LVAs.

Table 1.

Main components of interventions provided in the three arms of the trial

| Conventional low vision rehabilitation (CLVR) | Enhanced low vision rehabilitation (ELVR) | Controlled for additional contact time in enhanced low vision rehabilitation (CELVR) |

| • Check a patient’s understanding of the diagnosis and prognosis • Discuss needs/visual requirements and set initial goals • Assess vision (including sight test and near acuities) • Re-appraise goals • Demonstrate specific LVAs • Explain use and handling of prescribed LVAs • Advise about lighting and other methods of enhancing vision • Provide large print literature about diagnosis, vision enhancement, use of LVAs and other services • Refer to other services where necessary (eg, to ahospital support worker) • Arrange for follow ups, usually at 3 months withadditional appointments being offered if necessary | As for conventional LVR, plus up to three home visits (at approximately 2 weeks, 4–8 weeks, and at 4–6 months after the first low vision assessment) by a trained rehabilitation officer to: • advise on use of LVA(s): assess patterns of LVA use (eg, tasks attempted, frequency and duration of use) and difficulties experienced in using LVAs; • demonstrate and supply alternative or additional LVAs, if appropriate; • provide wider patient support—eg, direct patients to relevant support and welfare services | As for conventional LVR, plus up to three home visits (at approximately 2 weeks, 4–8 weeks, and at 4–6 months after the first low vision assessment) by a community care worker to: • discuss ability to cope with daily activities • discuss ability to take part in leisure activities • discuss other problems or topics raised by participant |

Participants allocated to ELVR received all components of CLVR but, in addition, received additional low vision training at home. A rehabilitation officer, with specific training in the rehabilitation of people with visual impairment and 5 years’ experience in this role, provided the home visits. Although he was familiar with the techniques of eccentric viewing and steady eye strategy, the main emphasis of the intervention was on LVA handling, the use of alternative LVAs, and other strategies for enhancing vision (for example, use of contrast and lighting). The rehabilitation officer was, for example, able to check in the home environment that a subject was using: the correct working distance, appropriate lighting, the correct eye and/or spectacles, and provide instruction in appropriate page navigation—for example, for stand magnifiers. He was able to offer alternative LVAs should a person be struggling with a device provided in the hospital clinic and issue new devices in the event that a person raised an additional problem area that might be ameliorated with LVAs. He received a report of the optometric assessment for a participant before making a home visit and maintained a link with the low vision clinic by providing a report to the hospital following each home visit and by regular visits to the clinic.

Participants allocated to CELVR also received all components of CLVR but, in addition, were visited at home by one of four community care workers from Age Concern (see table 1). Community care workers do not have training about visual impairment or any formal training in low vision. Hence, they did not provide any specific LVR. The community care workers did not have any formal link with the hospital through a reporting system and did not visit the low vision clinic.

Outcomes

A range of outcomes were assessed before the first hospital assessment and about 12 months later:

Vision specific QoL (VCM1)21; this instrument has 10 items addressing patients’ feelings about their visual impairment and the impact of low vision on their lives;

Generic health related QoL (SF-36)22;

Psychological adjustment to vision loss (Nottingham Adjustment Scale)23,24 relevant, stand alone sections were selected from this instrument, covering “attitudes” to visual impairment, “locus of control,” “acceptance,” and “self efficacy”;

Measured task performance at 12 months only, using a LVA if desired; participants were asked to read “use by dates” on two supermarket grocery items and pharmacy instructions on a medicine bottle;

Self rated restriction in everyday activities because of visual impairment and use of LVAs. These outcomes were derived from the Manchester Low Vision Questionnaire.16 Self rated restriction was scored as a proportion—that is, the number of tasks from a predefined list that participants reported being unable to do (but wanted to do) divided by the total number of tasks that they wanted or needed to be able to do; use of LVAs was summarised by yes/no responses to two questions—that is, using a LVA at least daily, and using a LVA on average for more than 5 minutes each time the LVA is used), with the aim of distinguishing short term LVA use for “survival” tasks and longer term use for leisure or social activities.16,25

Outcomes (a) to (c) were scored according to published instructions. The original eight dimensions of the SF-36 were combined into two dimensions—namely, “physical” and “mental” component summary scores (PCS and MCS).26

We chose vision specific QoL as the primary outcome measure. However, we believe that QoL in AMD patients is complex and therefore included the other outcome measures to try to characterise this complexity.27 Final outcomes (that is, health related and vision specific QoL, MLVQ, and task performance) were assessed at home before the third scheduled clinic assessment. Patients with final outcomes recorded were included in analyses irrespective of whether they had attended the third clinic assessment.

Sample size and plan of analysis

All QoL outcomes yielded continuous scales. There was no information at the start of the trial on the size of effect that might be observed or that would be regarded as an important QoL improvement by people with visual impairment. A target sample size of 75 participants in each arm of the trial was set to detect a standardised difference between any pair of groups of 0.46 with 80% power at a 5% (two tailed) significance level—that is, a “moderate to small” effect.

Differences in outcome between arms of the trial at 12 months were estimated by regression modelling, after adjusting for the corresponding baseline measurements when these were available. All analyses were by intention to treat. Differences were considered statistically significant if p<0.05. No subgroup comparisons were planned.

RESULTS

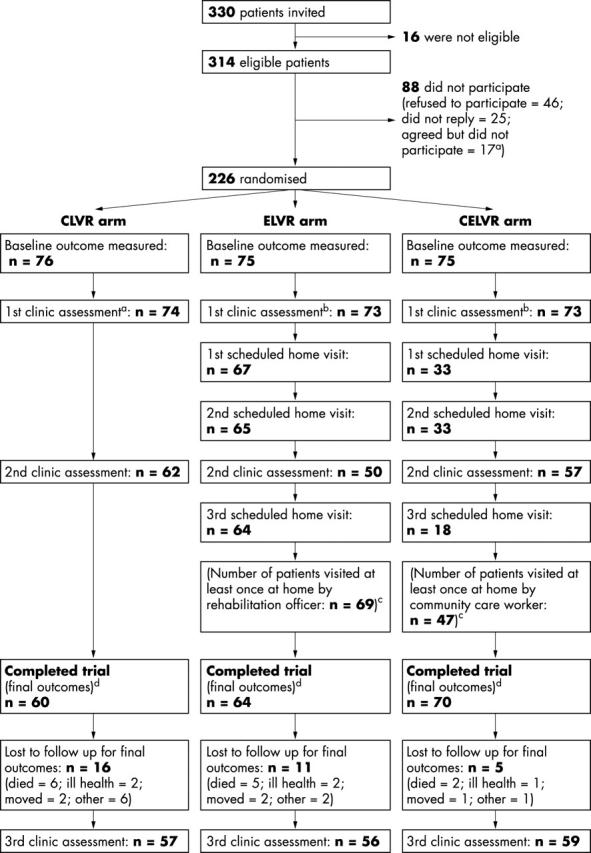

A total of 226 participants, with a median age of 81 years, were recruited between November 1997 and August 1999, of whom 194 (86%) completed the trial. The numbers of people invited and eligible, participants in each arm at the start and at various stages during the trial, and details of the home visits made in ELVR and CELVR arms are summarised in figure 1. The characteristics of participants are summarised in table 2.

Figure 1.

Study design. aNon-refusals who were not recruited: two patients died soon after consenting; 10 consented too late (that is, had consented after attending their first clinic assessment); four consented but lived too far away from the hospital; researcher failed to visit one patient because of researcher’s ill health. bFirst clinic assessments: two patients in CLVR arm died before their appointments; two patients in ELVR arm did not attend, one because of ill health and one for unknown reasons; one patient in CELVR arm died before appointment and one did not attend because of ill health. cHome visits: these are shown in the diagram as they were scheduled. However, because some visits had to be rearranged, the sequence of the home visits varied with respect to second clinical assessment varied for some patients. dDuration of follow up: mean durations of follow up (number of days between the first home visit to measure baseline outcomes and the last home visit to measure outcomes after 12 months’ follow up) were 361, 364, and 362 in CLVR, ELVR, and CELVR arms, respectively.

Table 2.

Demographic and visual function characteristics of participants at baseline

| CLVR (n = 76) | ELVR (n = 75) | CELVR (n = 75) | ||||

| Median (n) | Q1–Q3 (%) | Median (n) | Q1–Q3 (%) | Median (n) | Q1–Q3 (%) | |

| Age (years) | 81 | 77–84 | 80 | 76–85 | 83 | 78–86 |

| Female | 48 | 63% | 48 | 64% | 54 | 72% |

| Registered as blind or partially sighted: | ||||||

| Registered blind | 15 | 20% | 9 | 12% | 5 | 7% |

| Registered partially sighted | 21 | 28% | 17 | 23% | 19 | 25% |

| Not registered blind | 29 | 38% | 32 | 43% | 38 | 51% |

| Registration status not known | 11 | 14% | 17 | 23% | 13 | 17% |

| Home circumstances: | ||||||

| Living alone | 32 | 42% | 39 | 52% | 45 | 60% |

| Living with spouse | 40 | 53% | 21 | 28% | 26 | 35% |

| Living with family | 4 | 5% | 15 | 20% | 4 | 5% |

| Finished education ⩽14 years | 57 | 75% | 50 | 67% | 53 | 71% |

| Distance visual acuity (logMAR)† | 0.81 | 0.48–1.00 | 0.90 | 0.56–1.08 | 0.62 | 0.44–1.00 |

| Continuous text reading acuity (M units)‡ | 2.00 | 1.15–4.00 | 2.50 | 1.00–5.00 | 1.60 | 1.00–2.50 |

| Pelli-Robson contrast sensitivity§ | 0.90 | 0.60–1.05 | 0.83 | 0.45–1.05 | 1.00 | 0.60–1.05 |

†Distance visual acuity data were missing for four patients allocated to CLVR, two allocated to ELVR, and four allocated to CELVR.

‡Continuous text reading acuity data were missing for three patients allocated to CLVR, seven allocated to ELVR, and six allocated to CELVR.

§Contrast sensitivity data were missing for 20 patients allocated to CLVR, 17 allocated to ELVR, and 14 allocated to CELVR.

Data were missing because optometrists carrying out the low vision assessments sometimes failed to obtain or record the information, not because patients refused or were unable to perform the task.

Outcomes at baseline and at about 12 months after initial low vision assessment are shown in table 3. Outcome data were missing for some participants (see fig 1). There was some indication of differential loss to follow up across arms (21%, 15%, and 7% respectively for CLVR, ELVR, CELVR arms; χ2 = 6.45, df 2, p = 0.04), although the reasons for loss to follow up were distributed similarly in all groups.

Table 3.

Median outcomes or frequencies (and interquartile ranges or percentages) at baseline and after 12 months’ follow up

| CLVR | ELVR | CELVR | ||||

| Baseline (n = 76) | 12 months (n = 60) | Baseline (n = 75) | 12 months (n = 64) | Baseline (n = 75) | 12 months (n = 70) | |

| VCM1† | 2.1 (1.7 to 2.8) | 2.4 (1.8 to 3.1) | 2.2 (1.5 to 2.7) | 2.5 (1.7 to 3.0) | 2.2 (1.4 to 2.7) | 2.3 (1.5 to 2.9) |

| SF-36: PCS‡ | 36 (24 to 47) | 38 (24 to 44) | 33 (23 to 43) | 26 (14 to 40) | 31 (23 to 46) | 28 (17 to 41) |

| SF-36: MCS‡ | 52 (44 to 60) | 52 (43 to 59) | 56 (51 to 59) | 53 (41 to 57) | 53 (47 to 59) | 53 (45 to 57) |

| NAS§ | ||||||

| Locus of control | 17 (15 to 19) | 18 (14 to 20) | 18 (16 to 19) | 18 (14 to 20) | 18 (16 to 20) | 18 (16 to 20) |

| Acceptance | 35 (29 to 41) | 38 (27 to 41) | 36 (29 to 41) | 36 (29 to 42) | 37 (30 to 41) | 38 (29 to 42) |

| Attitude | 19 (16 to 24) | 20 (15 to 23) | 20 (17 to 24) | 20 (17 to 24) | 20 (17 to 23) | 19 (17 to 25) |

| Self efficacy | 28 (24 to 33) | 28 (24 to 33) | 29 (25 to 34) | 28 (23 to 33) | 28 (23 to 34) | 29 (24 to 34) |

| Measured task performance¶ | ||||||

| Read one or both use by dates | NA | 39 (66.1%) | NA | 39 (61.9%) | NA | 54 (77.1%) |

| Read drug name | NA | 32 (55.2%) | NA | 30 (46.9%) | NA | 43 (61.4%) |

| MLVQ | ||||||

| Self rated restriction score†† | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.7) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.7) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.7) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.7) | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.6) | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.6) |

| Using at least one LVA‡‡ | 52 (91.2%) | 57 (95.0%) | 62 (100%) | 58 (90.6%) | 58 (92.1%) | 67 (95.7%) |

| Using an LVA daily‡‡ | 36 (63.2%) | 42 (70.0%) | 45 (72.6%) | 47 (73.4%) | 43 (68.3%) | 51 (72.9%) |

| Using an LVA for ⩾5 minutes‡‡ | 32 (56.1%) | 18 (30.0%) | 35 (56.5%) | 22 (34.4%) | 33 (52.4%) | 16 (22.9%) |

NA, measured task performance and LVA use were not assessed at baseline.

†VCM1 scores are the average of 10 items, each scored from 0 to 5, with larger scores representing poorer vision related QoL.

‡SF-36 PCS and MCS component scores are normalised “T” scores—that is, a “normal” population is assumed to have a mean of 50 and SD of 10, with higher scores represent better QoL. Baseline data were incomplete for three patients allocated to CLVR, four allocated to ELVR, and two allocated to CELVR; 12 month follow up data were incomplete for onepatient allocated to ELVR.

§Minimum and maximum NAS scores for each dimension were 4–20 for locus of control, 9–45 for acceptance, 7–35 for attitude, and 8–40 for self efficacy, with larger scores representing “a more desirable state of affairs.”21 Baseline and 12 month follow up data for “acceptance” were incomplete for one patient allocated to ELVR; 12 month follow up NAS data for “attitude” were incomplete for one allocated to CLVR, and for “self efficacy” for one allocated to ELVR..

¶Task performance scores are frequencies (percentages); data at 12 months were missing for reading use by dates for one patient allocated to CLVR and one allocated to ELVR, and for reading medicine instructions for two allocated to CLVR,

††Baseline self rated restriction scores ranged from 0 to 1, with larger scores representing greater restriction. Data were incomplete for six patients allocated to CLVR, six allocated to ELVR, and nine allocated to CELVR; 12 month follow up data were incomplete for two patients allocated to CLVR and two allocated to ELVR.

‡‡Frequencies (percentages) are reported for these outcomes; all percentages are with respect to the total number of patients completing the trial in each arm. Baseline data were not collected, but LVA use was assessed at 4 months; however, some patients could not be contacted at 4 months to assess LVA use and denominators for CLVR, ELVR and CELVR were 57, 62, and 63.

Differences in outcomes between arms at 12 month follow up are summarised in table 4, showing all three comparisons between pairs of arms separately. There were few significant differences in outcome between arms. Where differences were observed, these tended to favour CLVR, not ELVR or CELVR—for example, for the SF-36. (Because of the number of multiple comparisons (multiple outcomes and many pairwise comparisons between groups), it would not be unusual to observe one or two statistically significant differences by chance.)

Table 4.

Effect size estimates for all pairwise comparisons between arms

| Effect size (scale units) | 95% CI | p Value | ||

| (A) For scaled trial outcomes (ie, differences between arms at 12 months) | ||||

| VCM1†: | ||||

| ELVR v CLVR | 0.06 | −0.17 to 0.30 | 0.60 | |

| ELVR v CELVR | 0.12 | −0.11 to 0.34 | 0.31 | |

| CELVR v CLVR | −0.05 | −0.29 to 0.18 | 0.64 | |

| SF-36†: | ||||

| PCS | ELVR v CLVR | −6.05 | −10.2 to −1.91 | 0.004 |

| ELVR v CELVR | −3.78 | −7.75 to 0.19 | 0.06 | |

| CELVR v CLVR | −2.27 | −6.29 to 1.76 | 0.27 | |

| MCS | ELVR v CLVR | −4.04 | −7.44 to −0.65 | 0.02 |

| ELVR v CELVR | −2.56 | −5.73 to 0.61 | 0.11 | |

| CELVR v CLVR | −1.48 | −4.69 to 1.73 | 0.36 | |

| NAS†: | ||||

| Locus of control | ELVR v CLVR | −0.42 | −1.68 to 0.83 | 0.51 |

| ELVR v CELVR | −0.44 | −1.63 to 0.76 | 0.47 | |

| CELVR v CLVR | 0.02 | −1.21 to 1.25 | 0.98 | |

| Acceptance | ELVR v CLVR | −0.36 | −3.04 to 2.32 | 0.79 |

| ELVR v CELVR | −0.73 | −3.29 to 1.84 | 0.58 | |

| CELVR v CLVR | 0.36 | −2.24 to 2.97 | 0.78 | |

| Attitude | ELVR v CLVR | 0.22 | −1.34 to 1.77 | 0.79 |

| ELVR v CELVR | 0.03 | −1.52 to 1.45 | 0.97 | |

| CELVR v CLVR | 0.25 | −1.27 to 1.77 | 0.75 | |

| Self efficacy | ELVR v CLVR | −0.44 | −2.88 to 2.00 | 0.72 |

| ELVR v CELVR | −0.88 | −3.21 to 1.44 | 0.46 | |

| CELVR v CLVR | 0.44 | −1.91 to 2.79 | 0.71 | |

| Self rated restriction score†: | ||||

| ELVR v CLVR | 0.04 | −0.02 to 0.11 | 0.17 | |

| ELVR v CELVR | 0.04 | −0.02 to 0.10 | 0.15 | |

| CELVR v CLVR | −0.00 | −0.06 to 0.06 | 0.99 | |

| (B) For binary trial outcomes (ie, odds ratios for 12 months data) | ||||

| †Analysis was adjusted for baseline outcome score; participants with data missing at baseline were excluded from the analysis. | ||||

| ‡All 194 participants who completed the trial were included in the analysis of “using at least one LVA”; analyses of “using a LVA daily” and “for > 5 minutes” were restricted to the 95% of participants using at least one LVA at 12 months. | ||||

| Measured task performance: | ||||

| Read at least one “Use by date” | ELVR v CLVR | 0.83 | 0.40 to 1.75 | 0.63 |

| ELVR v ELVR | 0.48 | 0.23 to 1.02 | 0.06 | |

| CELVR v LVR | 1.73 | 0.80 to 3.76 | 0.17 | |

| Read medicine name (±dose) | ELVR v CLVR | 0.72 | 0.35 to 1.46 | 0.36 |

| ELVR v CELVR | 0.55 | 0.28 o 1.10 | 0.09 | |

| CELVR v LVR | 1.29 | 0.64 to 2.62 | 0.48 | |

| LVA use‡: | ||||

| Using at least one LVA | ELVR v CLVR | 0.51 | 0.12 to 2.13 | 0.36 |

| ELVR v ELVR | 0.43 | 0.10 to 1.81 | 0.25 | |

| CELVR v LVR | 1.18 | 0.23 to 6.05 | 0.85 | |

| Using a LVA daily | ELVR v CLVR | 1.18 | 0.54 to 2.59 | 0.67 |

| ELVR v ELVR | 1.03 | 0.48 to 2.21 | 0.94 | |

| CELVR v LVR | 1.15 | 0.54 to 2.48 | 0.72 | |

| Using a LVA for >5 minutes on average | ELVR v CLVR | 1.22 | 0.57 to 2.60 | 0.60 |

| ELVR v ELVR | 1.77 | 0.83 to 3.78 | 0.14 | |

| CELVR v LVR | 0.69 | 0.32 to 1.52 | 0.36 | |

During follow up all visual functions deteriorated—for example, VA dropped by 0.2 logMAR (two lines of the letter chart). Deteriorations in VCM1 and SF-36 scores were also statistically significant but were small in absolute terms. All other outcomes remained fairly constant. Although changes over time were not the focus of interest of the study, these findings suggest that the study population was becoming generally more infirm as well as more visually impaired as the trial progressed.

After 12 months, 94% of participants reported using at least one LVA, similar to the 95% who reported using a LVA at 4 months. (Data about LVA use at 4 months were obtained at the second clinic assessment, but LVA use at this stage of follow up was not specified as an outcome in the protocol.) Most (72%) used LVAs daily for short term “spot” reading tasks but about a third said that, on average, they used their LVA for more than 5 minutes at a time. Despite the observed deterioration over time in visual function (VA and contrast sensitivity) and quality of life (VCM1 and SF36), participants reported only a small reduction in self rated restriction in activities.

DISCUSSION

This trial found no evidence of benefit from the model of enhanced LVR evaluated, compared with CLVR. Overall, the visual function and general health of the study population appeared to deteriorate over time. Use of LVAs was high throughout the trial and, if anything, increased with duration of follow up.

We have no reason to question the validity of the trial. Randomisation was concealed, ruling out selection bias. The researcher who measured outcomes was blinded, although some patients became unmasked during the assessment (at 12 months, the researcher correctly “guessed” arm allocation for 51% of participants compared to 33% expected by chance). Unmasking could have introduced information bias although such bias would have been expected to lead to an exaggerated benefit of ELVR rather than no effect.

Despite a median age of 82 years, 72% (226/314) of eligible people agreed to take part. Of the 226 recruited, 194 (86%) completed the trial, an excellent completion rate given the elderly study population. The most frequent reason for loss to follow up was death, which cannot have introduced bias. Death and other reasons for follow up were distributed similarly across groups, although the total number lost to follow up was greater in the CLVR group, primarily for “other” reasons (for example, bereavement, not at home for final assessment on two occasions). It is possible that those who were lost to follow up had selectively poorer or better QoL, but the small numbers lost for reasons other than death would have had only a very small effect on the mean QoL for each group. The intervention was set in the context of a typical HES low vision service, which provides the majority of LVR appointments.10 These statistics suggest that the findings are likely to be highly applicable in the United Kingdom.

Optimism about models of enhanced vision rehabilitation both in the United Kingdom14 and abroad12,17—that is, extending the training aspects of providing LVAs, makes it important to consider possible reasons for the ineffectiveness of the intervention, compared with CLVR:

The intervention may not have included critical elements. However, there is no established model of enhanced LVR—for example, whether enhancement should focus on visual training14,17 or integration of services.9 The present trial primarily focused on the former. Critics may claim that one or more aspects of training were not included but no accepted model of enhanced visual training has yet been established. Our working hypothesis was that improved ability to perform tasks should translate into improved QoL and we included components that were practicable (deliverable at reasonable cost). The home based intervention in the present trial comprised an average contact time of less than 2 hours per patient whereas Nilsson et al17 report an average contact time of ∼5 hours. The only specific omission was systematic training in eccentric viewing strategies to optimise vision in the presence of a central scotoma, for which we would argue there is no recognised protocol with proved effectiveness. (There are methodological limitations to the trial reported by Nilsson et al17; the sample size was extremely small, the assessment of outcomes was unmasked with considerable possibility of bias, and it is unclear whether the subjects being trained were benefiting from training in the use of LVAs or from eccentric viewing itself.) Consequently, we think it is unlikely that this reason explains the failure to find benefit from ELVR.

CLVR provided by the HES may have already remedied faults for which it has previously been criticised13—for example, inadequate provision of appropriate training and support following prescription of LVAs, before the trial started. We have no information to support or refute this possibility.

The outcome measures chosen may have been inappropriate or insensitive to the benefits afforded by the intervention. The intervention focused primarily on facilitating everyday activities and our primary outcome measure (VCM1) is, arguably, weighted more to psychological aspects of visual impairment. (The more widely used vision specific QoL instrument, the NEI-VFQ25,28 may be more sensitive to restrictions in activities but it was not available when the trial started. Other vision specific QoL instruments have also been published since the trial started—for example, the “LVQOL”.29) However, we assessed task performance and self rated restriction in activities, neither of which showed any differences between arms. Therefore, we think it is unlikely that this reason explains the failure to find benefit from ELVR, compared with CLVR.

Home visits for ELVR were provided by a single rehabilitation officer who may have been ineffective in providing the intended training and support. He had previously undertaken a full time course in, and obtained a certificate of, Higher Education in Rehabilitation Work with Visually Impaired People. In addition, before his involvement in the trial, he had 4 years’ experience working as a visual rehabilitation officer and had undertaken pretrial training by optometrists in the low vision clinic at the hospital. Again, we think it is unlikely that this reason explains the failure to find benefit from ELVR. Using a team of rehabilitation officers, while potentially more applicable, would have been logistically more difficult and would still have been open to the same criticism.

The ability of people with AMD to carry out everyday activities with a LVA may not be as relevant to their QoL as we assumed. Other researchers have shown that AMD causes a reduction in QoL4,5 and the baseline SF-36 PCS data (compared with a “normal” score of 50) show that this was also true for our study population. QoL of the participants did not improve during follow up despite high, and increasing, use of LVAs. If QoL is not strongly linked to restriction in everyday activities, one might not predict any differences between arms. We believe that this explanation is potentially very important. One possibility is that the QoL of people with AMD is primarily determined by grief for lost sources of pleasure and relaxation—for example, reading, playing with grandchildren, or watching television rather than by their ability to perform essential activities in a constrained way. If true, it may be worth considering interventions more usually associated with bereavement or chronic conditions, such as counselling,30 as well as traditional task oriented interventions.

The lack of improvement in most outcomes over time for CLVR might lead some to question the effectiveness of CLVR. However, such a comparison is uncontrolled—that is, it does not consider the extent to which QoL may deteriorate in the absence of LVR entirely, and CLVR compared to no LVR has never been evaluated. The widespread use of LVAs on a daily basis for tasks that participants rated as important to them suggests strongly that people with AMD value LVAs highly. Most participants made frequent use of LVAs but for short periods of time on each occasion. Whether or not this pattern of use constitutes successful rehabilitation may be debatable. However, our findings on LVA use are comparable to those of another large study on the use of LVAs in the elderly—namely, that of Watson et al.31 These researchers profiled low vision device use in 200 US veterans and also found that the majority of subjects tended to use optical LVAs for a few minutes at a time. Therefore, we believe that our findings on LVA use are a realistic reflection of low vision device use in older people.

Given the limitations of medical interventions for AMD, from a purely descriptive point of view the trial has highlighted the need to develop effective interventions because of the QoL impact of AMD. AMD causes a considerable disability burden and the number of AMD sufferers can only increase in future years. If an intervention could enhance the ability of people with AMD to live independently, as well as improving QoL, it would also have the potential to be cost effective.

CONCLUSIONS

ELVR as evaluated in this trial appears to be no more effective than CLVR. The manifest lack of additional benefit from ELVR, despite its face validity, should make researchers cautious about developing and advocating modified or supplementary interventions without more in-depth preliminary evidence of their effectiveness. We recommend that researchers consider carefully the determinants of reduced QoL in people affected by AMD and the ability of interventions to address them, before designing and evaluating new interventions. A RCT of no LVR (or delayed LVR) versus conventional LVR has been proposed in the United States32 but is not being carried out because of lack of funding (Raasch TW, personal communication, 2004). There would be much merit in conducting such a trial.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the help of the following: first and foremost, the participants, who showed such strong commitment to the trial; optometrists at the Manchester Royal Eye Hospital for completing study data sheets when carrying out low vision assessments; consultants at the Manchester Royal Eye Hospital for their support for the trial and for allowing us to recruit their patients; Professor D McLeod for advice and support throughout; Henshaws Society for the Blind and Richard Bounds for their cooperation in providing the ELVR intervention; and Age Concern for their cooperation in providing community care workers for the CELVR intervention.

Abbreviations

AMD, age related macular degeneration

CLVR, conventional low vision rehabilitation

ELVR, enhanced low vision rehabilitation model

HES, hospital eye service

LVA, low vision aid

LVR, low vision rehabilitation

QoL, quality of life

RCT, randomised controlled trial

The trial was funded by North West Regional Health Authority (research grant RDO/18/39); Manchester Royal Eye Hospital General Research endowment fund.

Conflict of interest: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Evans J , Wormald R. Is the incidence of registrable age-related macular degeneration increasing? Br J Ophthalmol 1996;80:9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey PT. Common eye diseases of elderly people: identifying and treating causes of vision loss. Gerontology 2003;49:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin GS, Bandee-Roche K, Huang GH, et al. The association of multiple visual impairments with self-reported visual disability: SEE project. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001;42:64–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams RA, Brody BL, Thomas RG, et al. The psychosocial impact of macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116:514–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mangione CM, Gutierrez PR, Lowe G, et al. Influence of age-related maculopathy on visual functioning and health-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol 1999;128:45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chong NHV, Bird AC. Alternative therapies in exudative age related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol 1998;82:1441–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beatty S , Au Eong KG, McLeod D, et al. Photocoagulation of subfoveal choroidal neovascular membranes in age related macular degeneration: the impact of the macular photocoagulation study in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland. Br J Ophthalmol 1999;83:1103–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meads C , Salas C, Roberts T, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-utility of photodynamic therapy for wet age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2003;7:1–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Low Vision Services Consensus Group. Recommendations for future service delivery in the UK. London: Royal National Institute for the Blind, 1999.

- 10.Culham LE, Ryan B, Jackson AJ, et al. Low vision services for vision rehabilitation in the United Kingdom. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:743–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan B , Culham L. Fragmented vision. Survey of low vision services in the UK. London: Royal National Institute for the Blind and Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Trust, 1999.

- 12.Nilsson UL, Nilsson SE. Rehabilitation of the visually handicapped with advanced macular degeneration. Doc Ophthalmol 1986;62:345–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McIllwaine GG, Bell JA, Dutton GN. Low vision aids—is our service cost-effective? Eye 1991;5:607–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shuttleworth GN, Dunlop A, Collins JK, et al. How effective is an integrated approach to low vision rehabilitation? Two year follow up results from south Devon. Br J Ophthalmol 1995;79:719–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watson GR, De L’Aune W, Stelmack J, et al. National survey of the impact of low vision device use among veterans. Optom Vis Sci 1997;74:249–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harper RA, Doorduyn K, Reeves BC, et al. Evaluating the outcomes of low vision rehabilitation. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 1999;19:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nilsson UL. Visual rehabilitation with and without educational training in the use of optical aids and residual vision. A prospective study of patients with advanced age-related macular degeneration. Clin Vis Sci 1990;6:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brody BL, Williams RA, Thomas RG, et al. Age-related macular degeneration: a randomized clinical trial of a self-management intervention. Ann Behav Med 1999;21:322–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg R , Faye E, Fischer M, et al. Role of prism relocation in improving visual performance of patients with macular dysfunction. Optom Vis Sci 1989;66:747–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russell WB, Harper R, Reeves BC, et al. Randomised controlled trial of an optometric versus an integrated low vision rehabilitation service for people with age-related macular degeneration: study design and methodology. Ophthal Physiol Opt 2001;21:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frost NA, Sparrow JM, Durant JS, et al. Development of a questionnaire for measurement of vision-related quality of life. Ophthal Epidemiol 1998;5:185–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dodds AG, Bailey P, Pearson A, et al. Psychological factors in acquired visual impairment: the development of a scale of adjustment. J Vis Impairment Blindness 1991;85:306–10. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dodds AG, Flannigan H, Ng L. The Nottingham Adjustment Scale: a validation study. Int J Rehab Res 1993;16:77–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russell WB. An enhanced versus an optometric low vision rehabilitation service for people with age-related macular degeneration: a randomised controlled trial. PhD thesis. Manchester: University of Manchester, 2003.

- 26.Jenkinson C , Layte R, Wright L, et al. The UK SF-36: an analysis and interpretation manual. 2nd ed. Oxford: Health Services Research Unit, University of Oxford, 1996:1–66.

- 27.Harper RA, Reeves BC, Russell WB. Visual impairment, disability and quality of life in AMD: a longitudinal study. Ophthalmic Res 2001;33 (S1) :102.11244356 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mangione CM, Berry S, Spritzer K, et al. Identifying the content area for the 51-item National Eye Institute visual function questionniare. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116:227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolffsohn JS, Cochrane AL. Design of the Low Vision Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (LVQOL) and measuring the outcome of low-vision rehabilitation. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;130:793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brody BL, Gamst AC, Williams RA, et al. Depression visual acuity, comorbidity and disability associated with age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2001;108:1893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watson GR, De L’Aune W, Stelmack J, et al. National survey of the impact of low vision device use among veterans. Optom Vis Sci 1997;74:249–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raasch TW. Design of an intervention trial in low vision. In: Activity and participation. 7th International Conference on Low Vision, International Society for Low Vision Research and Rehabilitation 2002:27.