Abstract

Aim: To assess whether povidone-iodine provided any benefit over and above a standard regimen of antibiotic therapy for the treatment of corneal ulcers.

Methods: All patients diagnosed with corneal ulcers presenting for care at a primary eye care clinic in rural Nepal were randomised to a standard protocol of antibiotic therapy versus standard therapy plus 2.5% povidone-iodine every 2 hours for 2 weeks. The main outcomes were corrected visual acuity and presence, size, and position of corneal scarring in the affected eye at 2–4 months following treatment initiation.

Results: 358 patients were randomised and 81% were examined at follow up. The two groups were comparable before treatment. At follow up, 3.9% in the standard therapy and 6.9% in the povidone-iodine group had corrected visual acuity worse than 20/400 (relative risk (RR) 1.77, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.62 to 5.03). 9.4% in the standard therapy and 13.1% in the povidone-iodine group had corrected visual acuity worse than 20/60 (RR 1.39, 95% CI 0.71 to 2.77), and 17.0% and 18.8% had scars in the visual axis in each of these groups, respectively (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.82).

Conclusions: A small proportion of patients with corneal ulceration treated in this setting had poor visual outcomes. The addition of povidone-iodine to standard antibiotic therapy did not improve visual outcomes, although this design was unable to assess whether povidone-iodine on its own would have resulted in comparable visual outcomes to that of standard therapy.

Keywords: corneal ulcers, povidone-iodine, Betadine, randomised trial

Ocular trauma is a major cause of monocular blindness and visual impairment worldwide.1–4 In rural south Asia, ocular trauma frequently leads to infective ulceration of the cornea.5–9 A high proportion of these corneal ulcers are fungal, but treatment options for fungal ulcers are limited because of the expense and lack of available medications.5,10–12 Antibacterial treatment is cheaper and more readily available, but is not effective against fungal infections. Even for bacterial corneal ulcers, the availability of antibiotics in such settings can be problematic, and a topical application of a medication such as povidone-iodine would probably be even more available and cheaper than standard antibiotics.

A 5% solution of povidone-iodine is widely used prophylactically to reduce the risk of infection during cataract surgery.13–24 Several studies have shown that it is very effective against bacteria.13–22,24 It has also been shown to be effective against a number of viruses, fungi, and spores,23,25–27 although a recent study found 1% povidone-iodine to be ineffective against Aspergillus fungal keratitis in rabbits.28 It has been used for the prophylaxis of ophthalmia neonatorum and was effective against Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and herpes simples type II.29,30 It has also been used to treat conjunctivitis, keratitis, and corneal ulcers.23,31–34 A 5% solution of povidone-iodine has been suggested as a “pan-anti-infective eye drop” for the treatment of a number of ophthalmic conditions in developing countries.35

Based on the studies suggesting povidone-iodine might be beneficial in the resolution of corneal ulcers, and its bactericidal, antiviral, and antifungal properties, the specific aim of this trial was to assess the efficacy of 2.5% povidone-iodine administered topically every 2 hours for 14 days in addition to a standard regimen of antibacterial therapy in healing corneal ulceration, reducing the size of corneal scarring, and improving the final visual acuity in a rural setting where eye injuries are common, no antifungal therapies are available, and referral options are limited by distance, availability of transport, and costs of ophthalmic care.

METHODS

The trial was conducted among patients with corneal ulcers who present for treatment to the Hariaun Eye Clinic in Sarlahi district, Nepal. The clinic was established in 1991, as part of a package of services delivered to the community participating in a large, USAID sponsored vitamin A supplementation trial being conducted by Johns Hopkins University, the Nepal National Society for Comprehensive Eye Care, and the Sushil Kedia Seva Mandhir, a local non-governmental organisation.36,37 The district lies about 8 hours’ drive south of Kathmandu in the low lying terai region of Nepal, bordering the state of Bihar in India, and has a population of about half a million people. At the time of the trial, the eye clinic provided the only Western style eye care for the district. The nearest eye hospital was 4–6 hour journey by bus. The clinic was staffed by a senior ophthalmic assistant with 15 years of experience working in this area. He conducted all the examinations for the study and was supervised by an ophthalmologist from the Nepal Eye Hospital, Kathmandu, who visited the clinic on a regular basis. The training and measurement of acceptable agreement is the same approach we have followed in previous ocular studies for these two observers.37–40 The ophthalmic assistant had a slit lamp and a limited number of medications with which to treat corneal ulcers and other eye conditions.

All patients living in the area covered by the community randomised vitamin A trial who presented to the clinic with corneal ulcers were asked if they would be willing to participate in a randomised trial of treatment for their ulcers. There were no exclusions based on age or sex. Patients who had corneal perforation or impending perforation were included in the trial and given treatment, but were referred for further care to the nearest eye hospital. Those with bilateral corneal ulcers, ectropion with exposure of the cornea, seventh nerve palsy, lagophthalmos, and patients with known allergic reactions to iodine were excluded from the study. The excluded patients were referred to the nearest eye hospital for treatment not available at the clinic. Verbal informed consent was obtained from patients 16 years of age and older. Consent was obtained from at least one parent for children under 16 years of age. If patients under 16 years of age were married and no longer living with their parents, consent was obtained from the patient. Patients who did not give verbal informed consent were excluded. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Committee on Human Research of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and from the Nepal Health Research Council.

Patient presenting for treatment of a corneal ulcer who met the eligibility criteria were randomised to receive (1) standard antibiotic therapy alone, or (2) standard therapy plus povidone-iodine (2.5% povidone-iodine every 2 hours for 14 days) (table 1). The length of antibiotic application varied by severity of the ulcer, but treatment was continued until the ulcer healed. The rationale for the dosage and frequency of povidone-iodine was based on evidence in the literature for the safety of this regimen and the desire for initial frequent application. The decision to change from one line of therapy to another was made at the discretion of the clinician if there was no improvement after 3–7 days. The definition of a corneal ulcer included evidence of loss of corneal epithelium with an underlying stromal infiltrate by slit lamp examination. However, the definition of a corneal ulcer was difficult to standardise under these conditions. For this reason, a secondary analysis was conducted in the subset of patients with hypopyon. These cases would constitute more severe but more clearly defined ulceration.

Table 1.

Definitions of standard therapy for corneal ulcers

| Standard therapy for corneal ulcers without hypopyon: |

| 1st line: chloramphenicol drops, 1 drop every 2 hours |

| chloramphenicol ointment, 2 times daily |

| mydriatic: homatropine drops or atropine ointment as required |

| 2nd line: gentamicin eye drops, 1 drop every 2 hours |

| chloramphenicol ointment, 2 times daily |

| mydriatic as above |

| 3rd line: gentamicin eye drops, 1 drop every 2 hours |

| tetracylcine ointment, 2 times daily |

| mydriatics as above |

| Standard therapy for corneal ulcers with hypopyon: |

| Subconjuntival injection of gentamicin (0.5 ml) given at every visit until resolved |

| Systemic antibiotic and painkillers are given in severe cases as per decision of clinician |

Randomisation was assigned in blocks of 10. The assignment for each patient was maintained in a sealed envelope with the patient number recorded on the outside. Numbers were assigned sequentially as patients presented for care and agreed to participate. The envelope was opened and the assigned treatment provided to that patient. Treatments were not masked to the clinician or the patient since povidone-iodine has such a distinctive colour. The projected sample size was 170 patients per treatment group. This was based on the assumption of a 50% prevalence of follow up visual acuity of worse than 20/60 in the standard therapy group, a 35% prevalence in the povidone-iodine group, a type I error of 5%, and power 80% to detect this difference.

At the time of enrolment, patients were interviewed about demographic and socioeconomic information. The eye examination consisted of visual acuity measurements, examination using loupes, direct ophthalmoscope, and a slit lamp. Other information collected during the examination included degree of conjunctival injection, fraction of the cornea affected by the ulcer, whether it was in the visual axis, whether the ulcer appeared to be sterile, bacterial, fungal or viral, presence of or extent of hypopyon, flare and cell, corneal precipitates, corneal vascularisation, and presence of pain. Visual acuity measurements were made using an ETDRS tumbling E chart. Subjective refraction and best corrected visual acuity were also obtained.

Patients were asked to return within 3 days to assess success of treatment. Treatment failure was defined as a corneal ulcer that increased in circumference or depth after 3 or 4 days of treatment. Cases of failure after the third line of standard therapy or if corneal perforation was imminent, were referred to the nearest eye hospital. Follow up information was collected at each visit with regard to treatment and changes to treatment, as well as visual acuity. However, we anticipated a low percent of patients would return to the clinic for follow up owing to the high cost of transport for people with very small (if any) cash incomes. Hence, the clinician visited all patients at home 2–4 months after their enrolment in the study, measured visual acuity, and conducted a brief anterior segment examination. The primary outcome was corrected visual acuity in the eye with the corneal ulcer (using an illiterate E ETDRS chart) at the 2–4 month home visit. Correction in this setting was done by assessing pinhole acuity. Other outcomes were the presence, size and position of corneal scarring, and rate of treatment failure at follow up clinic visits (corneal ulcer got worse or did not heal and referral was necessary). Prevalence of these outcomes was compared using relative risks and 95% confidence intervals around these estimates.

RESULTS

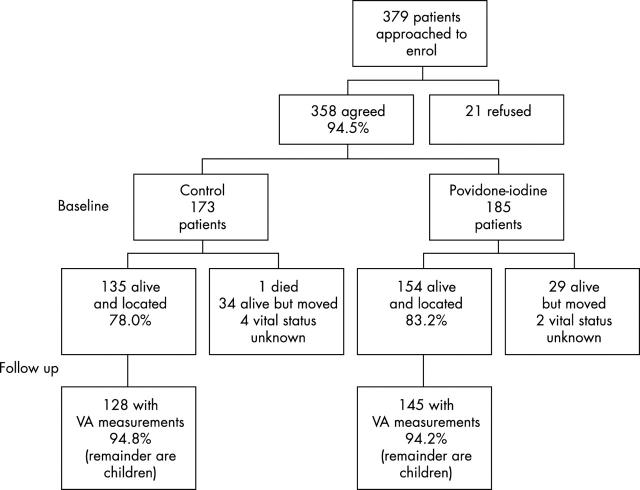

A total of 379 patients were eligible for the trial and 358 (94.5%) agreed to participate (fig 1). Of these, 173 were randomised to standard therapy and 185 to standard therapy plus povidone-iodine. Among the standard therapy group, 135 (78.0%) were examined at the 2–4 month home visit, and 154 (83.2%) were examined in the povidone-iodine group. Visual acuity at follow up was obtained on 94.5%, which was similar in both groups. The remaining patients were children whose visual acuity could not be ascertained because they were too young.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of eligibility, enrolment, and follow up of patients randomised to standard of care or standard of care plus povidone-iodine for treatment of corneal ulcers.

Participants had a similar age distribution and a similar proportion was male (table 2). The ocular characteristics of patients on presentation to the clinic were similar in terms of the fraction of the cornea affected, whether the ulcer was in the visual axis, presence of corneal rupture and hypopyon, and presenting and corrected acuity in the affected eye (table 3).

Table 2.

Baseline demographic characteristics of trial participants

| Standard therapy (n = 173) | Povidone-iodine (n = 185) | |||

| No | % | No | % | |

| Age at presentation | ||||

| <10 | 10 | 5.8 | 14 | 7.6 |

| 10–19 | 28 | 16.2 | 38 | 20.5 |

| 20–29 | 39 | 22.5 | 40 | 21.6 |

| 30–39 | 29 | 16.8 | 40 | 21.6 |

| 40–49 | 30 | 17.3 | 30 | 16.2 |

| 50+ | 37 | 21.4 | 23 | 12.4 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 126 | 72.8 | 114 | 61.6 |

| Female | 47 | 27.2 | 71 | 38.4 |

Table 3.

Baseline ocular characteristics of trial participants

| Standard therapy (n = 173) | Povidone-iodine (n = 185) | |||

| No | % | No | % | |

| Ulcer in the visual axis* | 72 | 41.6 | 81 | 44.3 |

| Hypopyon | 13 | 7.6 | 17 | 9.2 |

| Corneal rupture | 4 | 2.3 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Fraction of cornea affected† | ||||

| <1/3 | 106 | 62.0 | 125 | 69.4 |

| 1/3–2/3 | 50 | 29.2 | 42 | 23.3 |

| >2/3 | 15 | 8.8 | 13 | 7.2 |

| Corrected acuity in affected eye | ||||

| ⩾20/20 | 41 | 25.2 | 45 | 26.0 |

| <20/20–⩾20/60 | 73 | 44.8 | 74 | 42.8 |

| <20/60–⩾20/400 | 26 | 16.0 | 33 | 19.1 |

| <20/400 | 23 | 14.1 | 21 | 12.1 |

*Could not be assessed for 2 patients in the povidone-iodine group.

†Could not be assessed in 2 patients in the standard therapy group and 5 patients in the povidone-iodine group.

10 patients in the standard therapy group and 12 patients in the povidone-iodine group were too young for acuity measurements.

Sixty one patients in the standard care group (35.3%) and 60 (32.4%) in the povidone-iodine group returned for a follow up visit to the clinic (table 4). Three standard care and eight povidone-iodine patients returned for a second follow up visit, and one standard care patient returned for a third visit. Of those who returned, the proportion having their medication changed because of treatment failure was similar in both groups (29.5% and 33.3% in the standard care and povidone-iodine groups, respectively). There was no difference in pain, redness, swelling, or itching between the two groups. Those in the povidone-iodine group reported more tearing at the first follow up visit but this difference was not statistically significant. A total of 12.1% in the standard care and 11.5% in the povidone-iodine groups sought treatment elsewhere. More than half in each group went to Kathmandu for care (53% in the standard care group, and 83% in the povidone-iodine group).

Table 4.

Side effects and treatment failures by treatment group

| State of eye | Standard therapy | Povidone-iodine | ||||||||||

| 1st Visit | 2nd Visit | 3rd Visit | 1st Visit | 2nd Visit | 3rd Visit | |||||||

| N = 61 | % | N = 3 | % | N = 1 | % | N = 60 | % | N = 8 | % | N = 0 | % | |

| Pain | 15 | 24.6 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 100.0 | 15 | 25.0 | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Redness | 17 | 27.9 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 100.0 | 20 | 33.3 | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Swelling | 6 | 9.8 | 1 | 33.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 6.7 | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Itching | 4 | 6.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Pus | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Tearing | 14 | 23.0 | 2 | 66.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 19 | 31.7 | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Feels better | 50 | 82.0 | 3 | 100.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 46 | 76.7 | 6 | 75.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Medication changed | 18 | 29.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 20 | 33.3 | 6 | 75.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

The percentage with corrected visual acuity of <20/400 at the final visit in the affected eye was 3.9% in the standard care and 6.9% in the povidone-iodine group (RR: 1.77, 95% CI 0.62, 5.03) (table 5). About two thirds of patients had a final corrected visual acuity of 20/20 or better in the affected eye, and this was the same in both treatment groups; 43.8% of standard care and 31.7% of povidone-iodine patients improved by four or more lines. Most of this difference was in the patients whose baseline visual acuity was <20/400. Eighty per cent of the standard care group with initial visual acuity of <20/400 (16 out of 20) improved by four or more lines, while only 52.9% of patients (nine out of 17) in the povidone-iodine group improved this amount from baseline to final examination. Seventeen per cent of standard care patients and 18.8% of povidone-iodine patients had corneal scars that were in the visual axis at the final examination (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.82). Types of scars in the visual axis that were most common were macula (8.1% of standard care and 11.0% of povidone-iodine patients) and leucomas (6.7% of standard care and 7.1% of povidone-iodine patients). Of those with scars in the visual axis, 5.2% in each group had vascularisation of the scar.

Table 5.

Visual outcomes at 2–4 month home visit by treatment group

| Standard therapy (n = 135) | Povidone-iodine (n = 154) | |||

| No | % | No | % | |

| Corneal scar in the visual axis | 23 | 17.0 | 29 | 18.8 |

| Corrected acuity in affected eye | ||||

| ⩾20/20 | 81* | 63.3 | 95# | 65.6 |

| <20/20–⩾20/60 | 35 | 27.3 | 31 | 21.4 |

| <20/60–⩾20/400 | 7 | 5.5 | 9 | 6.2 |

| <20/400 | 5 | 3.9 | 10 | 6.9 |

| Change in acuity in eye with ulcer | ||||

| Worse | 3 | 2.3 | 13 | 9.0 |

| Same | 38 | 29.7 | 44 | 30.3 |

| 1 line better | 11 | 8.6 | 20 | 13.8 |

| 2 lines better | 16 | 12.5 | 18 | 12.4 |

| 3 lines better | 4 | 3.2 | 4 | 2.8 |

| 4 lines better | 18 | 14.1 | 17 | 11.7 |

| >4 lines better | 38 | 29.7 | 29 | 20.0 |

*7 patients in the standard therapy group, and 9 patients in the povidone-iodine group were too young for visual acuity measurements.

To better understand the impact of treatment cases that were clearly severe, we examined those patients with hypopyon on presentation, 7.6% and 9.2% of standard care and povidone-iodine patients. More than 90% had visual acuity of <20/400 at that time, and 84.6% and 94.1% had an ulcer in the visual axis. Forty per cent of patients in each group had a final corrected visual acuity of <20/400 in the affected eye, and 75.0% in the standard care and 78.6% in the povidone-iodine group had a corneal scar in the visual axis at the final visit. Hence, even among more serious cases, there did not appear to be a difference in visual outcomes by treatment group.

DISCUSSION

This randomised trial found no benefit of 2.5% povidone-iodine every 2 hours for 2 weeks for the treatment of corneal ulcers, when given in addition to standard antibacterial therapy available in this rural environment, although povidone-iodine was well tolerated and signs and symptoms of side effects were comparable in the two treatment groups. The strengths of this study are the randomisation to treatment groups, the use of one clinical observer that eliminates interobserver bias, and the relatively low loss to follow up in a remote rural setting because home visits were conducted, and only those who had moved or died could not be examined.

One limitation of the study was the lack of microbiological typing of infections. It is possible that we would not see a difference in treatment groups if many of the ulcers were not fungal and the standard therapy was adequate to treat bacterial ulcers. The Aravind Eye Hospital in Madurai, south India, found 52% of corneal ulcers that could be cultured to be fungal in aetiology, whereas a hospital based study in north India found 8.4% to be fungal.10,11 In Nepal, corneal ulcers presenting to Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital from 1985–7 found 17% of culture positive ulcers were fungal.5 The slit lamp findings, while not definitive, suggest that there were few ulcers whose clinical appearance could be considered fungal. It is possible that corneal abrasions may have been enrolled and treated in additional to ulcers. In this setting, it was also not possible to use time to complete epithelialisation as an outcome rather than final visual acuity because a slit lamp examination could not be done at each home.

The original sample size was based on 50% of patients in the control group having a final visual acuity of worse than 20/60, but the percentage was much lower, 9.4% versus 13.1% in the standard care and povidone-iodine groups, respectively. This is a 39% higher prevalence of the outcome in the povidone-iodine group than the standard care group, but the power to detect this difference is only 19%. Hence, we cannot conclude that povidone-iodine was worse than the standard therapy, given the sample size and prevalence of the primary outcome. Among those with hypopyon on presentation, the proportion with final visual acuity of worse than 20/60 was about 70% in both groups, more in line with our original assumptions on which the sample size was based.

Another limitation of this study was that the treatments were not masked to the clinician and the same clinician examined the patients at presentation and follow up. Povidone-iodine has an obvious colour and it was considered unacceptable, ethically, to provide a placebo treatment. Because of the remote setting and limited availability of clinicians, it was not possible to have a different person complete the final home visit assessment. However, this is unlikely to bias the clinician since he would no longer remember which treatment he gave each patient by the time of the home visit. The only time when bias might have been present as a result of inability to mask the treatments would have been when decisions regarding change of treatments because of the treatment failure were required.

Because of the time between presentation and the follow up home visit, we did not ask about adherence to treatments. If poor adherence to the povidone-iodine regimen was present, then this might be another explanation for a lack of treatment effect. However, there is no reason to think adherence was poorer because of side effects in the povidone-iodine group based on comparability of side effects in both groups at the follow up visits. There is also the possibility of a “wash out” effect when more than one topical treatment is prescribed.41 We were unable to ascertain which of the two topical treatments patients took first or how long they waited between instillation of the drops.

Although this trial showed no benefit of adding povidone-iodine to the current standard of care for corneal ulcers, povidone-iodine alone may be an effective treatment for corneal ulcers when compared to current standard of care in this environment. We were unable to test this because of ethical concerns of withholding the standard therapy without close follow up and adequate evidence for efficacy of povidone-iodine to treat corneal ulcers. Such a study might be done in an environment where closer follow up were possible (alleviating safety concerns, and improving the ability to monitor compliance). The advantage of povidone-iodine is primarily its cost and easy access in countries like Nepal. As a 2.5% solution, povidone-iodine is well tolerated and produced no more side effects than the standard therapy in this population. Recent research suggests that future work should focus on assessing the efficacy of povidone-iodine alone, or other similarly inexpensive medications such as chlorohexidine,42–44 in comparison with standard therapy or each other, in an environment where microbiological results are available and patients can be followed closely and provided with alternative therapies in the event of treatment failure.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work came from Cooperative Agreement HRN-A-00-97-00015-00 between the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Nepal National Society for Comprehensive Eye Care, Kathmandu, Nepal, the Sushil Kedia Seva Mandhir, and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The portable slit lamp for the study was donated by Humphrey Zeiss. We thank the Data Safety and Monitoring Board: Chair, Maurecu Maguire, Alan Robin, Douglas Jabs, and John Gottsch.

Series editors: W V Good and S Ruit

REFERENCES

- 1.Thylefors B . Epidemiological patterns of ocular trauma. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1992;20:95–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seva Foundation. Epidemiology of blindness in Nepal. Chapter 9, Trauma. MI: Chelsea, 1988.

- 3.Negrel AD, Thylefors B. The global impact of eye injuries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 1998;5:143–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith GT, Taylor HR. Epidemiology of corneal blindness in developing countries. Refract Corneal Surg 1991;7:211–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Upadhyay MP, Karmacharya PCD, Koirala S, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics, predisposing factors, and etiologic diagnosis of corneal ulceration in Nepal. Am J Ophthalmol 1991;111:92–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitcher JP, Srinivasan M. Corneal ulceration in the developing world: a silent epidemic. Br J Ophthalmol 1997;81:622–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzales CA, Srinivasan M, Witcher JP, et al. Incidence of corneal ulceration in Madurai District, South India. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 1996;3:159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srinivasan M , Gonzales CA, George C, et al. Epidemiology and aetiological diagnosis of corneal ulceration in Madurai, south India. Br J Ophthalmol 1997;81:965–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Upadhyay MP, Karmacharya PC, Koirala S, et al. The Bhaktapur Eye Study: ocular trauma and antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of corneal ulceration in Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:388–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srinivasan M , Gonzales CA, George C, et al. Epidemiology and aetiological diagnosis of corneal ulceration in Madurai, south India. Br J Ophthalmol 1997;81:965–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chander J , Sharma A. Prevalence of fungal corneal ulcers in northern India. Infection 1994;22:207–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leck AK, Thomas PA, Hagan M, et al. Aetiology of suppurative corneal ulcers in Ghana and south India, and epidemiology of fungal keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:1211–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Apt L , Isenberg S, Yoshimori R, et al. Chemical preparation of the eye in ophthalmic surgery. III. The effects of povidone-iodine on the conjunctiva. Arch Ophthalmol 1984;102:728–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Apt L , Isenberg S, Yoshimori R, et al. Outpatient topical use of povidone-iodine in preparing the eye for surgery. Ophthalmology 1989;96:289–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apt L , Isenberg S. Chemical preparation of skin and eye in ophthalmic surgery: An international survey. Ophthalmic Surg 1982;13:1026–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimes SR, Mein CE, Trevino S. Preoperative antibiotic and povidone-iodine preparation of the eye. Ann Ophthalmol 1991;23:263–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagoutte F , Fosse T, Jasinski M, et al. Povidone iodine (Betadine) for the prophylaxis of postoperative infection. A multicentre study. J Fr Ophtalmol 1992;15:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boes DA, Lindquist TD, Fritsche TR, et al. Effects of povidone-iodine chemical preparation and saline irrigation on the perilimbal flora. Ophthalmology 1992;99:1569–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caldwell DR, Kastl PR, Cook J, et al. Povidone-iodine: its efficacy as a perioperative conjunctival and periocular preparation. Ann Ophthalmol 1984;16:577–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klie F , Boge-Rasmussen I, Jensen OL. The effect of polyvinyl-pyrrolidone-iodine as a disinfectant in eye surgery. Acta Ophthalmol 1986;64:67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Speaker MG, Menikoff JA. Prophylaxis of endophthalmitis with topical povidone-iodine. Ophthalmology 1991;98:1769–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ariyasu RG, Nakamura T, Trousdale MD, et al. Intraoperative bacterial contamination of the aqueous humor. Ophthalmic Surg 1993;24:367–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hale ML. Povidone-iodine in ophthalmic surgery. Ophthalmic Surg 1970;1:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isenberg S , Apt L, Yoshimori R, et al. Chemical preparation of the eye in ophthalmic surgery. IV. Comparison of povidone-iodine on the conjunctiva with a prophylactic antibiotic. Arch Ophthalmol 1985;103:1340–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saggers BA, Stewart GT. Polyvinyl-pyrrolidone-iodine: an assessment of anti-bacterial activity. J Hygiene 1964;62:509–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gershenfeld L . Povidone-iodine as a topical antiseptic. Am J Surg 1957;94:938–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White JH, Stephens GM, Cinotti AA. The use of povidone-iodine for treatment of fungi in rabbit eyes. Ann Ophthalmol 1972:855–6. [PubMed]

- 28.Panda A , Ahuja R, Biswas NR, et al. Role of 0.02% polyhexamethylene biguanide and 1% povidone iodine in experimental apergillus keratitis. Cornea 2003;22:138–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benevento WJ, Murray P, Reed CA, et al. The sensitivity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and herpes simplex type II to disinfection with povidone iodine. Am J Ophthalmol 1990;109:329–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isenberg SJ, Apt L, Yoshimori R, et al. Povidone-iodine for ophthalmia neonatorum prophylaxis. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;118:701–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hale LM. The treatment of corneal ulcer with povidone-iodine (Betadine). N C Med J 1969;30:54–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuwahara Y , Ohta Y, Yamada M. Experience with PVP-iodine. J Clin Ophthalmol 1962;16:93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sloan JB. Povidone-iodine to treat pseudomonas corneal ulcers. Abstract, 7th Annual staff meeting of the University of North Carolina Department of Ophthalmology 1969.

- 34.Hale LM. Treatment of experimental herpes simplex keratitis with povidone-iodine. Abstract, 7th Annual staff meeting of the University of North Carolina Department of Ophthalmology 1969.

- 35.Taylor J . Appropriate drugs for developing countries. Int Ophthalmol 1990;14:173–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West KP, Katz J, Khatry SK, et al. Double blind, cluster randomized trial of low dose supplementation with vitamin A or beta-carotene on mortality related to pregnancy in Nepal. BMJ 1999;318:570–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khatry SK, Lewis AE, Schein OD, et al. The epidemiology of ocular trauma in rural Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol 2004;88:456–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katz J , West KP, Khatry SK, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for trachoma in Sarlahi district, Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol 1996;80:1037–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katz J , West KP, Khatry SK, et al. The impact of vitamin A supplementation on prevalence and incidence of xerophthalmia in Nepal. Inv Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1995;36:2577–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khatry SK, West KP, Katz J, et al. Epidemiology of xerophthalmia in Nepal: a pattern of household poverty, childhood illness and mortality. Arch Ophthalmol 1995;113:425–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chrai SS, Makoid MC, Eriksen SP, et al. Drop size and initial dosing frequency problems of topically applied ophthalmic drugs. J Pharm Sci 1974;63:333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin MJ, Rahman MR, Johnson GJ, et al. Mycotic keratitis: susceptibility to antiseptic agents. Int Ophthalmol 1996;19:299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rahman MR, Minassian DC, Srinivasan M, et al. Trial of chorhexidine gluconate for fungal corneal unlcers. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 1997;4:141–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rahman MR, Johnson GJ, Husain R, et al. Randomized trial of 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate and 2.5% natamycin for fungal keratitis in Bangladesh. Br J Ophthalmol 1998;82:919–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]