Abstract

Background/aims: In uveal melanoma monosomy 3 is emerging as a significant indicator of a poor prognosis. To date most cytogenetic studies of uveal melanoma have utilised fresh tissue or DNA extracted from tissue sections. In this study chromosome in situ hybridisation (CISH) was used to study monosomy 3 in tissue sections. The copy number of chromosome 3 was determined and related to patient survival.

Methods: Archival glutaraldehyde or formalin fixed, paraffin embedded material was obtained from 30 metastasising and 26 non-metastasising choroidal melanomas. Hybridisations were performed using centromere specific probes to chromosomes 3 and 18. Chromosome 18 was included as a control as previous abnormalities in uveal melanoma have not been described. Chromosomal imbalance was defined on the basis of changes in both chromosome index and signal distribution.

Results: CISH was successfully performed on both glutaraldehyde and formalin fixed tissue. Four cases were unsuccessful because of extensive tumour necrosis. All cases were balanced for chromosome 18. Monosomy 3 was detected in 15 of the 26 cases of metastasising melanoma; the 26 non-metastasising tumours were all balanced for chromosome 3. Monosomy 3 was significantly associated with metastases related death.

Conclusion: CISH can successfully identify monosomy 3 in archival glutaraldehyde or formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissue sections. Similar to previous studies monosomy 3 is a significant predictor of metastases related death.

Keywords: choroidal melanoma, monosomy 3

Uveal melanoma is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults with an estimated incidence of 4.3 per million per year in North America.1 With modern imaging there have been significant improvements in the accuracy of diagnosis as well as advances in the treatments available. Despite this the overall mortality of 16–53% remains unchanged owing to the propensity of uveal melanoma to metastasise to the liver.2,3 After clinical diagnosis of hepatic metastases life expectancy is extremely poor and the median survival time is only 7 months.4 It is generally accepted that the peak mortality from metastatic disease occurs within 3 years of diagnosis.2 However, the clinical course of patients with uveal melanoma is unpredictable and metastases may present up to 36 years later.5

Recently cytogenetic analyses of uveal melanomas have shown that loss of an entire chromosome 3 homologue (monosomy 3) often associated with an increased chromosome 8q shows a significant correlation with metastases and decreased survival.6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 Many of the techniques used in these studies require fresh tissue—for example, for cell culture used in standard cytogenetics15,16 and fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH)10,11 on dissociated tumour cells. Alternatively, DNA can be extracted from fresh or paraffin embedded tissue for analysis.7,17 None of the techniques described, however, has identified the presence or absence of monosomy 3 within tissue sections. For this study we have used the alternative approach of interphase cytogenetics. In interphase cytogenetics, probes specific to individual chromosomes can be hybridised to cell nuclei in their resting state between divisions as well as metaphase nuclei within a tissue section. The aim of this study was to adapt this technique to enable the identification of monosomy 3 in tissue sections from glutaraldehyde or formalin fixed, paraffin embedded archival melanomas and to correlate this analysis with patient survival.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study population

Archival specimens of choroidal malignant melanoma were obtained from the Western Infirmary Pathology files. The specimens included local resection and enucleation specimens from 30 patients who had died from metastatic melanoma and 26 patients who were either alive or had died from other causes after a minimum period of 7 years (mean 21 years, range 7–30 years). For patients with metastatic melanoma surgery was performed between 1975 and 1992 and for patients with non-metastasising melanoma surgery was performed between 1973 and 1991. Patients with metastatic melanoma were identified either from the cancer registry or case notes as having proved liver metastases by imaging, biopsy or postmortem examination. Patients without metastatic melanoma were both alive and well or had a cause of death other than metastatic melanoma and no evidence of metastatic disease at last follow up. All tissues had been previously fixed in glutaraldehyde or formalin and embedded in paraffin wax. Eight of the 26 cases of metastasising melanoma (MM) and four of the 26 cases of non-metastasising melanoma (NMM) had been formalin fixed (FF). The remaining tumours had all been fixed in glutaraldehyde fixed (GF). The FF and GF specimens were of similar ages. In 14 enucleation specimens (three FF and 11 GF) normal retina was used as an internal control. In addition, eight cases of normal human skin (all glutaraldehyde fixed) were included as an external control. After identification of cause of death all samples were anonymised and full ethical approval in accordance with local policy was obtained for the use of these tissue samples.

Tissue section preparation

Sections, 4 μm thick, were mounted on aminopropyltriethoxysilane coated glass slides. Before use, the slides were baked at 65°C for 4–24 hours. The tissue sections were dewaxed in 100% xylene and rehydrated in graded ethanol to water. Sections were microwaved in TRIS-EDTA (4.5 mM TRIS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8) at full pressure for 5 minutes. After rapid cooling the sections were then digested with pepsin (0.4% pepsin in 0.2 M hydrochloric acid) for 30 minutes at 37°C and post fixed for 10 minutes in tissue fixative (Streck Laboratories Inc, Omaha, NE, USA). Finally, sections were dehydrated in 100% ethanol and air dried.

DNA probes

Chromosome specific repetitive sequence probes for chromosome 3 (D3Z1) and chromosome 18 (D18Z1) were purchased from Q-Bio gene (Illkirch, France). Chromosome 18 was selected as a control chromosome as, to our knowledge, there are no reports describing alterations in uveal melanoma. Both commercial probes were ready labelled with digoxigenin. Probes were diluted 1:10 in a hybridisation mix consisting of 70% formamide, two times the standard concentration of standard saline citrate (SSC) (1×SSC is 0.15 M sodium chloride and 0.015 M sodium citrate, pH 7), 500 μg/ml salmon sperm DNA, and 10% dextran sulphate.

In situ hybridisation

The probe in the hybridisation mix and DNA in the tissue sections were co-denatured together using the Omnislide modular system (ThermoLife Sciences, Hampshire, UK) at 80°C for 5 minutes and then incubated at 37°C overnight. After hybridisation, slides were washed twice in 2× SSC at room temperature for 5 minutes and then in 1×SSC at 70°C for 5 minutes. Before immunohistochemical detection of hybridised probe the slides were washed in 4×SSCT (4×SSC, 0.05% Tween-20) and blocked for 30 minutes at room temperature in 4× SSCT, 10% blocking reagent (Roche, USA). The slides were then incubated with anti-digoxigenin alkaline phosphatase (AP) Fab fragments (Roche, USA) 1:500 dilution in 4×SSCT, 10% blocking reagent for 30 minutes at room temperature. Slides were washed in 4×SSCT for 5 minutes, and then rinsed in distilled water. The slides were then incubated in NBT/BCIP solution (0.4 mM nitroblue-tetrazolium (NBT), 0.38 mM 5-brom-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP), 1.25 M levamisole in 100 mM HCl pH 9.5, 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM magnesium chloride) overnight. The sections were rinsed in tap water and counterstained with haematoxylin. Sites of binding were identified as blue-black dots.

Quantification of hybridisation signals

Chromosome specific centromeric probes were hybridised to sections of choroidal melanoma. In order to obtain control values, centromeric copy numbers for the two chromosomes were assessed using retina where present in the tissue sections and normal skin. The evaluation and interpretation of in situ hybridisation signals were carried out as previously described.18,19 Briefly, tissue sections were examined by light microscopy using an oil immersion lens (magnification ×1000) and an eyepiece graticule to prevent recounting of nuclei. Overlapping nuclei and minor hybridisation signals were not analysed and only nuclei with the histological appearance of tumour cells were evaluated. Poor quality hybridisations were excluded. For each section the number of signal spots per nucleus was recorded for 200 nuclei and the assesser was masked to the outcome of the patient.

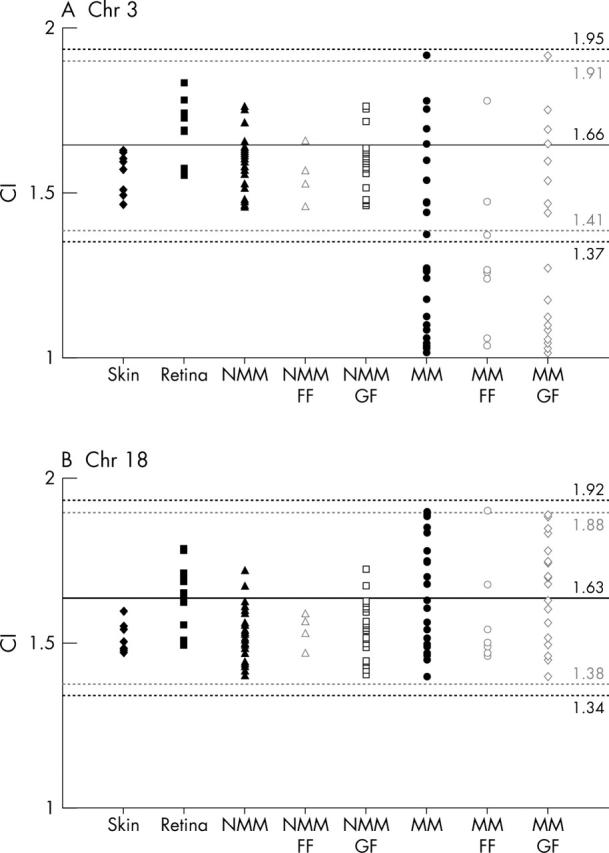

The hybridisation data were analysed in two ways to assess the degree of chromosome imbalance for each sample and each chromosome. Firstly, the chromosome index (CI), which gives an average chromosome copy number, was calculated by dividing the total number of hybridisation spots counted by the total number of nuclei counted. The CIs are shown in figure 1. For chromosome 3 the mean CI for retina and skin was 1.66 and 1.56 respectively. For chromosome 18 the mean CI for retina and skin was 1.63 and 1.51. A tumour was defined as monosomic for chromosome 3 if its CI was less than 3 SD from the mean (that is, less than 1.37).

Figure 1.

Scattergram showing distribution of chromosome index (CI) for chromosomes 3 (A) and 18 (B) in skin (solid diamond), retina (solid square), non-metastasising melanoma (NMM solid triangle); formalin fixed (FF, open triangle), glutaraldehyde fixed (GF, open square), and metastasising melanoma (MM solid circle; FF, open circle; GF, open triangle). The lines denotes the mean CI (solid line) (SD 3) (black broken lines) or 2.58 SD (grey broken lines) for retina. Values falling 3 SD below the mean were classified as chromosome loss.

The second method used to identify monosomy was the signal distribution, which can potentially detect relatively small populations with chromosomal numerical imbalances. To define the signal distribution the percentage of the nuclei counted with one, two or more than two hybridisation sites was calculated. A tumour was described as monosomic for chromosome 3 if the percentage of nuclei with one hybridisation site was greater than 60% of the nuclei counted.

The criteria for both signal distribution and CI were based on published estimates and previous experience of the technique and take into account nuclear truncation.18–20 Nuclear truncation is an important aspect of interphase cytogenetic analysis of 4 μm sections because a proportion of nuclei will lose DNA based on the diameter of the nucleus. Tumours had to show chromosome loss by both CI and signal distribution to be regarded as monosomic.

Statistical analysis

Differences in chromosomal indices between tumour and retina, GF and FF cases, and older and newer tissues were compared using the two sided Mann-Whitney test with a priori level of statistical significance set at p<0.05. The log rank test was used to compare survival with presence of monosomy 3, which was represented by a Kaplan-Meier survival curve.

RESULTS

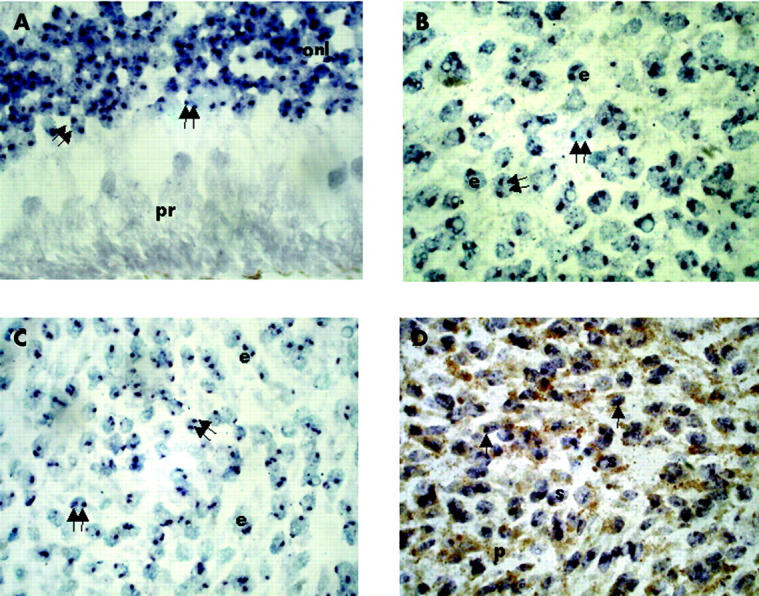

In situ hybridisation for chromosome 3 and 18 was successfully performed on 52 choroidal melanomas. Four cases were excluded because of heavy tumour pigmentation and large areas of necrosis. There was no apparent visual difference in hybridisation reactions in FF tumours when compared with GF tumours. Examples of choroidal melanomas and normal retina hybridised with chromosome 3 and 18 are shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Chromosome in situ hybridisation (CISH). (A) Glutaraldehyde fixed normal retina, hybridised with chromosome 18, showing two copies (double arrow) in most cells of the outer nuclear layer (onl). The photoreceptors (pr) are towards the bottom of the picture. (B) Glutaraldehyde fixed, metastasising epithelioid (e) melanoma, hybridised with chromosome 18, showing two copies (double arrow) in most cells. (C) Formalin fixed, non-metastasising epithelioid (e) melanoma, hybridised with chromosome 3, showing two copies (double arrow) in most cells. (D) Glutaraldehyde fixed, metastasising spindle (s) melanoma with moderate pigmentation (p), hybridised with chromosome 3, showing one copy in most cells (single arrow) (magnification ×1000).

Assessment of chromosome index

The CI for chromosome 3 and 18 in MM, NMM, and controls is shown in figure 1. There was no significant difference between the CI for FF tissues when compared with the corresponding GF tissues. There was no significant differences between the CI for tumours removed more than 20 years ago when compared with those removed less than 10 years ago. For both MM and NMM the CIs for chromosome 18 were not significantly different compared with that of normal retina and all lay within 2.75 SD of the mean CI for normal retina. For MM the CIs for chromosome 3 were significantly different compared with normal retina (p = 0.0013) and 15 of the 26 (58%) tumours had a CI more than 3 SD from the mean. For NMM the CIs for chromosome 3 were not significantly different compared with that of normal retina and all lay within 2 SD of the mean.

Assessment of signal distribution

For chromosome 18 the mean signal distribution for two or more hybridisation sites per nucleus was 64% for retina, 62% for skin, 52% for NMM (FF 52%; GF 52%), and 63% for MM (FF 62%; GF 64%). Therefore, by signal distribution all the samples were balanced for chromosome 18. For chromosome 3 the mean signal distribution for two or more hybridisation sites per nucleus was 63% for retina, 54% for skin, 55% for NMM (FF 53%; GF 56%), and 31% for MM (FF 30%; GF 32%). By signal distribution all the cases of normal retina, skin, and NMM were balanced for chromosome 3. However, by signal distribution 15 of the 26 cases of MM had more than 60% of nuclei with only one hybridisation site and were therefore defined as monosomic for chromosome 3 by this parameter (see table 1).

Table 1.

Signal distribution for chromosome 3 showing the percentage of nuclei with 40%, 50%, 60%, and 70% of nuclei with only one hybridisation site

| No of cases with over 40%, 50%, 60%, or 70% of tumour cell nuclei containing only one hybridisation site | ||||

| 40% | 50% | 60% | 70% | |

| Skin, n = 8 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Retina, n = 14 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NMM, n = 26 | 23 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| FF, n = 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| GF, n = 22 | 19 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| MM, n = 26 | 22 | 19 | 15 | 14 |

| FF, n = 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| GF, n = 18 | 15 | 12 | 9 | 9 |

NMM, non-metastasising melanoma; MM, metastasising melanoma; FF, formalin fixed; GF, glutaraldehyde fixed.

Assessment of monosomy 3

Tumours had to show chromosome loss by both CI and signal distribution to be regarded as monosomic and therefore the data for CI and signal distribution were combined to assess monosomy 3. The results are summarised in table 2. Using both criteria 15 of the 26 cases of MM were defined as monosomic for chromosome 3. All the NMM were balanced for chromosome 3. In all cases both parameters agreed and there were no cases where either the CI or signal distribution indicated monosomy but the other parameter did not.

Table 2.

Summary of chromosomal changes in choroidal melanoma as defined by agreement in both chromosomal index and signal distribution

| Chromosome 3 | Chromosome 18 | |||

| Loss | Balanced | Loss | Balanced | |

| Metastasising melanoma (n = 26) | 15 | 11 | 0 | 26 |

| Non-metastasising melanoma (n = 26) | 0 | 26 | 0 | 26 |

Relation between monosomy 3 and survival

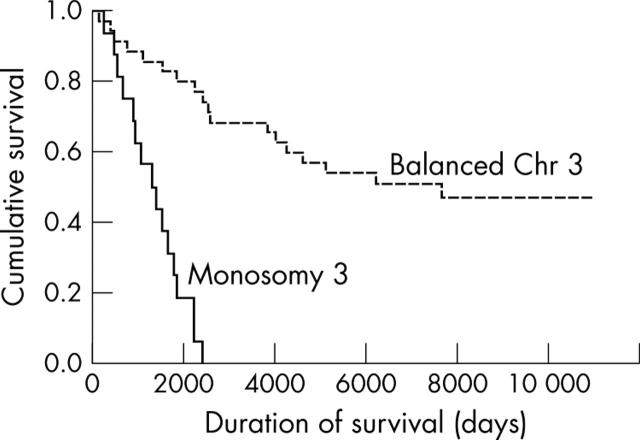

In patients who had died of metastatic disease the average time to death was 1349 days (range 120–4619 days). Monosomy 3 was significantly associated with metastasis related death (p<0.0001). This is shown in the Kaplan-Meier survival curve (fig 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve comparing survival with copy number for chromosome 3 as defined by agreement in both chromosome index and signal distribution.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study in which interphase cytogenetics has been applied to define the presence or absence of monosomy 3 in tissue sections of paraffin embedded choroidal melanomas. The main advantages of chromosome in situ hybridisation (CISH), used in this study, over other techniques are that it allows the direct assessment of chromosomal gains and losses in interphase and metaphase nuclei within a tissue section. This ensures that the nuclei assessed are indeed tumour cells and that the chromosomal changes within the tumour cells can be directly compared with adjacent normal tissue. CISH can be performed on archival tissue that is either formalin or glutaraldehyde fixed and we have already successfully performed CISH on glutaraldehyde fixed tissue samples up to 30 years old. In our laboratory CISH has previously been used to assess chromosomal gains and losses in other formalin fixed tumours such as adrenocortical tumours.21 In these tissues good hybridisation signals could be obtained when slides were simply pre-digested with pepsin for up to 1 hour. This method of tissue preparation worked for formalin fixed choroidal melanomas but we were unable to obtain signal with glutaraldehyde fixed tissues. However, by introducing a more rigorous pretreatment of microwaving under pressure in TRIS-EDTA buffer, before pepsin digestion, we were able to obtain good hybridisation signals. Interestingly, this additional step did not affect tissue preservation of formalin fixed cases and there were no significant differences between results obtained for CI and signal distribution between glutaraldehyde and formalin fixed cases. This pretreatment was therefore adopted for all cases in this study.

Using this technique we identified monosomy 3 in 15 of 26 (58%) of MM. All 26 NMM were balanced for chromosome 3. Both MM and NMM were balanced for chromosome 18. This chromosome was selected as a control as, to our knowledge, there are no reports indicating loss or gain of chromosome 18 in uveal melanoma. Using our criteria the results obtained for CI and signal distribution agreed in all cases of monosomy 3. Our cut-off points were selected in accordance with our laboratory’s previous experience of the technique. We defined a normal chromosome complement as 3 SD from the mean CI. Other researchers have used a value of 2.58 SD.22 If this value was applied to our study one case would not have been defined as monosomic by CI. However, for signal distribution we used a strict cut-off point of 60% of cells showing fewer than two hybridisation sites to define chromosomal loss compared with 40% or less used in other studies.23,24 In table 1 we have also shown the number of nuclei with 40%, 50%, and 70% of nuclei with only one hybridisation site. It is clear that in our laboratory a cut-off point of less than 60% would identify many normal tissues as monosomic. The identification of cells with only one hybridisation site in normal tissue reflects the effects of nuclear truncation and ultimately will be affected by the thickness of sections used, which may vary between studies. In this study we used 4 μm sections as this gave the best hybridisation signal. Using the higher cut-off point of 70% we would have excluded one case. This is the same case that would have been excluded by defining a cut-off point for CI 2.58 SD from the mean. This does not significantly alter our results but indicates that the cut-off points may have to be reassessed as more cases are studied. It is difficult to compare the number of cases of monosomy 3 identified in this study with other studies. In these studies monosomy 3 has been identified in 50–73% of choroidal melanomas but not all these studies differentiated non-metastasising from metastasising tumours and the follow up was shorter than in our study.

In this small study monosomy 3 was significantly associated with death from metastatic disease confirming the work of previous studies.6,7,11–14 Other techniques used for the assessment of non-random chromosomal abnormalities in uveal melanoma include standard cytogenetics,15,16 comparative genomic hybridisation,6,25 microsatellite analysis,7,12,26 and FISH.10,11,27 In standard cytogenetics, fresh tissue is required and disaggregated tumour cells are cultured and chromosomes analysed in metaphase. It has, however, been suggested that the cells which grow in culture may not be representative of the total tumour population.17 Comparative genomic hybridisation and polymerase chain reaction based microsatellite analysis have been undertaken on both fresh7,12 and archival paraffin embedded tissue.26 Both these techniques involve the extraction of DNA from the tissue samples. In comparative genomic hybridisation differentially labelled tumour and normal DNA samples are simultaneously hybridised to normal metaphase chromosomes. Regions of gains or losses within the tumour DNA can be identified by an increased or decreased colour ratio of the two fluorochromes used for the detection of hybridised DNA sequences along these reference chromosomes. In microsatellite analysis paired primers are used to amplify microsatellite markers on chromosomes of interest. Both these techniques are performed using DNA isolated directly from many tumour cells without culture and theoretically should more accurately represent the tumour cell population in vivo. However, tissue samples can be contaminated with non-tumour DNA that may be preferentially amplified during polymerase chain reaction. FISH has been used to describe cytogenetic abnormalities in uveal melanomas10,11,27 and by utilising different fluorochromes several chromosomes or chromosomal regions can be assessed simultaneously. The studies described, however, have utilised only fresh tissue and stained slides prepared from disaggregated tumour cells. FISH analysis for other chromosome regions has been performed on tissue sections of choroidal melanoma.28 In the study by Patel et al11 the authors comment that glutaraldehyde fixed tissue is not suitable for FISH analysis. CISH avoids the requirement for fresh tissue and the potential examination of non-representative tumour populations or non-tumour DNA. A further advantage of CISH is that different regions within a tumour, with, for example, different cell types may be analysed. This may help identify the emergence of subclones within a tumour and provide information on the role of monosomy 3 in tumour development.

Direct comparisons are not possible between the results of interphase cytogenetic studies and techniques that involve DNA extraction such as microsatellite analysis and comparative genomic hybridisation.29 Unlike these techniques the main disadvantage of the CISH technique described is that fine mapping of changes cannot be achieved with alpha repeat centromeric probes. Microsatellite analysis and comparative genomic hybridisation have shown that in the majority of cases chromosome 3 loss of heterozygosity involves an entire chromosome homologue; however, in a small number of tumours regional losses on chromosome 3 have been identified and such regional losses cannot be detected with this technique as it stands.7,17 However, probes for other chromosome regions are available and the technique could be adapted to detect regional losses. The technique could also be adapted to detect other chromosomes known to show gains or losses in uveal melanoma such as 8q14 and 6q,6 respectively. It is also not possible to characterise specific tumour suppressor genes that may be involved. None the less, CISH represents a valuable additional technique that will allow the study of monosomy 3 in tissue sections and therefore takes into account tumour heterogeneity allowing the correlation of genotype with phenotype. With CISH it will be possible to screen a large archival series and define a group of tumours for more detailed study using alternative cytogenetic techniques. Furthermore, it may refine the prognostic implications of monosomy 3 as regards short or long time to death from metastatic disease. Finally, the technique can easily be applied to routine pathology specimens without special treatment and could therefore identify high risk patients who may benefit from close monitoring.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mr Jim Ralston for his technical expertise and to Dr Ian McKay for his advice on statistics.

Abbreviations

CI, chromosome index

CISH, chromosome in situ hybridisation

FF, formalin fixed

FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridisation

GF, glutaraldehyde fixed

MM, metastasising melanoma

NMM, non-metastasising melanoma

REFERENCES

- 1.Singh AD, Topham A. Incidence of uveal melanoma in the United States: 1973–1997. Ophthalmol 2003;110:956–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diener-West M , Hawkins BS, Markowitz JA, et al. A review of mortality from choroidal melanoma. II. A meta-analysis of 5-year mortality rates following enucleation, 1966 through 1988. Arch Ophthalmol 1992;110:245–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergman L , Seregard S, Nilsson B, et al. Uveal melanoma survival in Sweden from 1960 to 1998. A review of mortality from choroidal melanoma. II. A meta-analysis of 5-year mortality rates following enucleation, 1966 through 1988. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003;44:3282–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kath R , Hayungs J, Bornfeld N, et al. Prognosis and treatment of disseminated uveal melanoma. Cancer 1993;72:2219–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newton FH. Malignant melanoma of choroid. Report of a case with clinical history of 36 years and follow up of 32 years. Arch Ophthalmol 1965;73:198–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aalto Y , Eriksson L, Seregard S, et al. Concomitant loss of chromosome 3 and whole arm losses and gains of chromosome 1,6, or 8 in metastasizing primary uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001;42:313–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scholes AGM, Liloglou T, Maloney P, et al. Loss of heterozygosity on chromosomes 3, 9, 13, and 17, including the retinoblastoma locus in uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001;42:2472–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sisley K , Parsons MA, Garnham J, et al. Association of specific chromosome alternations with tumour phenotype in posterior uveal melanoma. Br J Cancer 2000;82:330–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White VA, Chambers JD, Courtright PD, et al. Correlation of cytogenetic abnormalities with the outcome of patients with uveal melanoma. Cancer 1998;83:354–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naus NC, Verhoeven AC, van Drunen E, et al. Detection of genetic prognostic markers in uveal melanoma biopsies using fluorescence in situ hybridization Prediction of prognosis in patients with uveal melanoma using fluorescence in situ hybridisation. Clin Cancer Res 2002;8:534–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel KA, Edmondson ND, Talbot F, et al. Prediction of prognosis in patients with uveal melanoma using fluorescence in situ hybridisation. Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:1440–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scholes AG, Damato BE, Nunn J, et al. Monosomy 3 in uveal melanoma: correlation with clinical and histologic predictors of survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003;44:1008–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prescher G , Bornfeld N, Hirche H, et al. Prognostic implications of monosomy 3 in uveal melanoma. Lancet 1996;347:1222–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sisley K , Rennie IG, Parsons MA, et al. Abnormalities of chromosomes 3 and 8 in posterior uveal melanoma correlate with prognosis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1997;19:22–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horsman DE, White VA. Cytogenetic analysis of uveal melanoma. Consistent occurrence of monosomy 3 and trisomy 8q. Cancer 1993;71:811–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sisley K , Rennie IG, Cottam DW, et al. Cytogenetic findings in six posterior uveal melanomas: involvement of chromosomes 3, 6, and 8. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1990;2:205–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Speicher MR, Prescher G, du Manoir S, et al. Chromosomal gains and losses in uveal melanomas detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Res 1994;54:3817–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopman AH, Poddighe PJ, Moesker O, et al. In: Herrington CS, McGee JOD, eds. Diagnostic molecular pathology: a practical approach. Arlington, VA: IRL Press, 1992:141–67.

- 19.Murphy DS, Hoare SF, Going JJ, et al. Characterization of extensive genetic alterations in ductal carcinoma in situ by fluorescence in situ hybridization and molecular analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87:1694–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhingra K , Sneige N, Pandita TK, et al. Quantitative analysis of chromosome in situ hybridization signal in paraffin-embedded tissue sections. Cytometry 1994;16:100–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell AJ, Sibbald J, Haak H, et al. Increasing genome instability in adrenocortical carcinoma progression with involvement of chromosomes 3, 9 and X at the adenoma stage. Br J Cancer 1999;81:684–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bulten J , Poddighe PJ, Robben JCM, et al. Interphase cytogenetic analysis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Pathol 1998;152:495–503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sneige N , Sahin A, Dinh M, et al. Interphase cytogenetics in mammographically detected breast lesions. Hum Pathol 1996;27:330–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Visscher DW, Wallis TL, Crissman JD. Evaluation of chromosome aneuploidy in tissue sections of preinvasive breast carcinomas using interphase cytogenetics. Cancer 1996;77:315–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsechentscher F , Prescher G, Horsman DE, et al. Partial deletions of the long and short arm of chromosome 3 point to two suppressor genes in uveal melanoma. Cancer Res 2001;61:3439–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parrella P , Sidransky D, Merbs SL. Allelotype of posterior uveal melanoma: implications for a bifurcated tumor progression pathway. Cancer Res 1999;59:3032–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNamara M , Felix C, Davison EV, et al. Assessment of chromosome 3 copy number by fluorescence in situ hybridization and comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1997;98:4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker TM, van Ginkel PR, Gee RL, et al. Expression of angiogenic factors Cyr61 and tissue factor in uveal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:1719–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ried T . Interphase cytogenetics and its role in molecular diagnostics of solid tumors. Am J Pathol 1998;152:325–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]