The major risk factors for coronary heart disease include smoking, elevated blood pressure, and elevated serum cholesterol.1 Risk reduction starts with identification of those at risk and then alteration of factors such as discontinuation of smoking, lowering of blood pressure, and reduction of serum cholesterol. Patients who should have blood cholesterol testing include those with family history of premature coronary heart disease or hyperlipidaemia, personal history of coronary heart disease, or clinical evidence of elevated lipids with features of xanthelasma, corneal arcus under age 50 years, and cutaneous xanthomas at any age.1 Two of the latter clinical features are ophthalmic and detection relies on the ophthalmologist.

Xanthelasma appear as multiple yellow placoid lesions in the periocular skin and represent a concentration of lipocytes in the dermis.2 There are numerous methods to manage the cosmetic appearance of xanthelasma, which typically involves surgical excision or laser ablation.3 We report a novel approach to management using oral cholesterol lowering medication and patience.

Case report

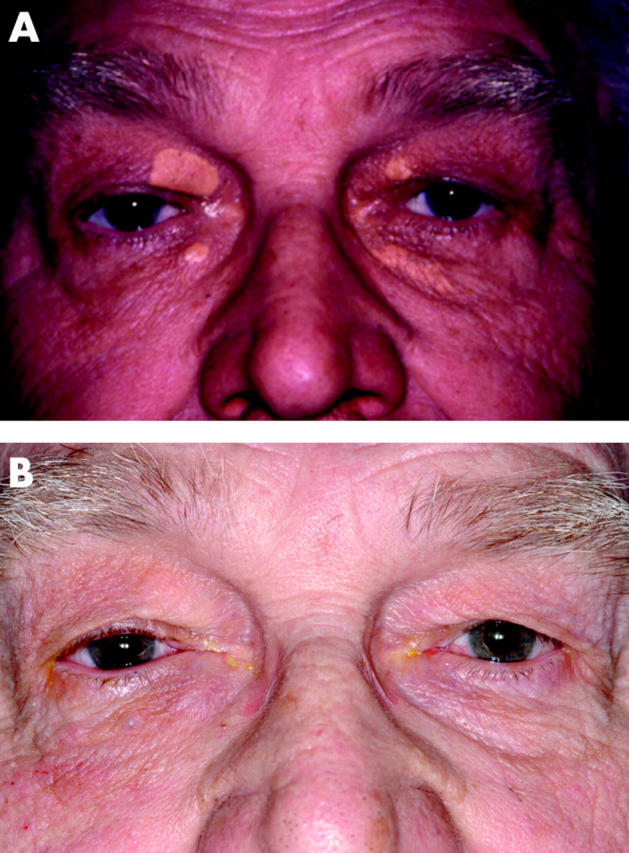

In 1992, a 68 year old male smoker with a history of hypertension and elevated serum cholesterol was referred for evaluation of a newly diagnosed iris mass. On examination, the visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes. The mass was diagnosed as a benign iris naevus and observation was advised. Coincidental bilateral medial canthal and upper and lower eyelid xanthelasma were detected (fig 1A). The largest xanthelasma measured 16 mm in diameter. Observation was advised with tentative plan for surgical excision in the future. The patient was advised to continue his antihypertensive medications and anticholesterol medication (oral simvastatin (Zocor) 20 mg once daily). At the 6 month follow up the iris nevus was stable and the xanthelasma persisted. Yearly examinations were advised. The patient did not return for 10 years. Surprisingly, the xanthelasma had completely resolved, leaving no clinical trace of subcutaneous lipid (fig 1B). He continued on his medications and serum cholesterol was normal.

Figure 1.

A 68 year old man with hypertension and elevated cholesterol and bilateral upper and lower eyelid xanthelasma. He was on oral simvastatin for hypercholesterolaemia. (A) January 1992. At presentation, the multifocal yellow xanthelasma are noted. (B) April 2002. After 10 years lost to ophthalmic follow up, the patient returned with complete resolution of xanthelasma.

Comment

In the Lipids Research Clinics Program Prevalence Study, xanthelasma and corneal arcus were associated with increased levels of serum cholesterol and low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), especially in young males.4 People with either lesion had increased odds of having type IIa dyslipoproteinaemia. Adjusted odds ratios for ischaemic heart disease in participants with xanthelasma and corneal arcus were generally increased. The study concluded that the clinical findings of xanthelasma or corneal arcus, especially in young people, helped to identify those with plasma lipoprotein abnormalities.4

Management of patients with elevated LDL-C include both low cholesterol diet and cholesterol lowering medications, the most popular of which are the statins. There are currently five statin drugs on the market in the United States and these include lovastatin (Mevacor, Altocor), simvastatin (Zocor), pravastatin (Pravachol), fluvastatin (Lescol), and atorvastatin (Lipitor). The major effect of these medications is to lower LDL-C by slowing down the production of cholesterol and by increasing the liver’s ability to metabolise the LDL-C in the blood. Statins reduce LDL-C by approximately 40% and produce a modest increase in high density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C). These medications are given daily in the evening to take advantage of the fact that the body makes more cholesterol at night. Statins reduce measured blood LDL-C within 4–6 weeks. In a study of 20 536 patients, this resulted in long term reduction in coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality.5

Simvastatin is derived synthetically from a fermentation product of Aspergillus tereus. Simvastatin is hydrolysed to an inhibitor of an enzyme responsible for cholesterol synthesis. In the Multicenter Anti-Atheroma Study, simvastatin slowed the progression of atherosclerosis, measured by vascular stenosis diameter on angiography, and decreased significantly the development of new lesions.5

To our knowledge, there have been no previous reports on the effect of statins on eyelid xanthelasma. A PubMed search for keywords “statin and xanthelasma” and simvastatin and xanthelasma” yielded no relevant publications. The management of eyelid xanthelasma includes surgical excision, microsurgical inverted peeling, laser inverted resurfacing, photovaporisation using carbon dioxide laser, and application of bichloracetic acid. Patients with the highest recurrence rate are those with elevated cholesterol. These local treatments do not address possible systemic associations. By observations in this report, we suggest that serum cholesterol be evaluated and if elevated, oral statin combined with dietary cholesterol restriction might result in resolution of xanthelasma over time, but, more importantly, reduction of patient cardiac risk.

Support provided by the Eye Tumor Research Foundation, Philadelphia, PA (CLS), the Macula Foundation, New York, NY (CLS), the Rosenthal Award of the Macula Society (CLS), and the Paul Kayser International Award of Merit in Retina Research, Houston TX (JAS).

References

- 1.Farmer JA, Gotto AM Jr. The Heart Protection Study: expanding the boundaries for high-risk coronary disease prevention. Am J Cardiol 2003;3:3i–9i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shields JA, Shields CL. Atlas of eyelid and conjunctival tumors. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, :138–9.

- 3.Rohrich RJ, Janis JE, Pownell PH. Xanthelasma palpebrarum: a review and current management principles. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;110:1310–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segal P, Insull W Jr, Chambless LE, et al. The association of dyslipoproteinemia with corneal arcus and xanthelasma. The Lipid Research Clinics Program Prevalence Study. Circulation 1986;73:108–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumont JM. Effect of cholesterol reduction by simvastatin on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: design, baseline characteristics, and progress of the Multicenter Anti-Atheroma Study (MAAS). Control Clin Trials 1993;14:209–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]