Abstract

Background: Antinuclear cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are useful diagnostic serological markers for the most common forms of necrotising vasculitis. ANCA associated vasculitides represent distinctive clinicopathological categories—for example, Wegener’s granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, microscopic polyangiitis, and idiopathic necrotising crescentic glomerulonephritis, collectively known as the small vessel pauci-immune vasculitides.

Method: Three cases of ANCA associated pauci-immune retinal vasculitis are described. Their systemic features are described and the clinical significance of ANCA as a diagnostic test in relation to retinal vasculitis discussed.

Results: These three cases represent a spectrum of clinical features associated with retinal vasculitis. Two cases have evolved into clinical recognisable entities as microscopic polyangiitis. Adherence to the international consensus statement on testing and reporting of ANCA is recommended and the authors speculate that the incidence of microscopic polyangiitis may be underestimated because of the under-recognition of systemic involvement in patients with retinal vasculitis.

Conclusion: The receipt of a positive ANCA result should always raise the suspicion of a pauci-immune systemic vasculitis and prompt appropriate investigation. The authors emphasise the importance of the evaluation of systemic features in these patients with retinal vasculitis, enabling earlier recognition and thereby preventing significant morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: ANCA, retinal vasculitis , microscopic polyangiitis

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA) are useful diagnostic serological markers for the most common forms of necrotising vasculitis providing a means of categorising vasculitides so that diagnostically shared pathological and clinical characteristics can be correlated.

ANCA produce two immunostaining patterns on alcohol fixed neutrophils: a cytoplasmic (C-ANCA) and a perinuclear (P-ANCA) pattern. P-ANCA’s main specificity is myeloperoxidase (MPO).1 C-ANCA is mainly produced by antibodies against PR3, a third serine protease from azurophilic myeloid granules.2 The international consensus statement on testing and reporting of ANCA was developed to minimise the technical difficulties of ANCA testing and its interpretation.3

It should be noted that systemic vasculitis may occur in the absence of a positive ANCA and, conversely, positive ANCAs may be found in the absence of vasculitis—for example, with infection and neoplasia. Receipt of a positive ANCA result should always raise the suspicion of a pauci-immune systemic vasculitis and prompt appropriate investigation.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 35 year old woman presented with pain and blurring of vision in her right eye. She related systemic complaints of malaise, lethargy, weight loss, and intermittent night sweats. Blood pressure was normal, urinalysis demonstrating moderate haem ++.

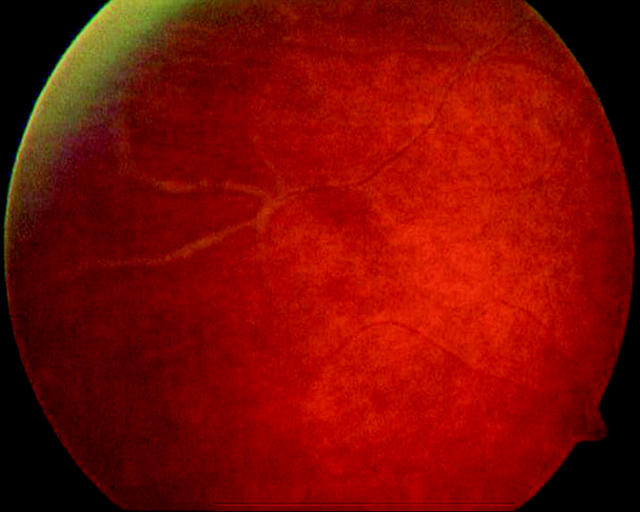

Examination demonstrated a right visual acuity of 3/60 (improving to 6/9 with pinhole). There were cells+ in the anterior chamber, the posterior segment demonstrating vitreous cells+++. Funduscopy revealed peripheral vascular sheathing (fig 1).

Figure 1.

Peripheral retinal vasculitis with vascular sheathing.

Blood results revealed a positive P-ANCA on immunofluorescence (MPO/PR3 testing not available at this time) with an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (94 mm in the first hour), and C reactive protein (20 mg/l). Serum antinuclear antibody testing was intermittently positive at 1:40 (on Hep2000 cells). Investigations for retinal vasculitis—namely, full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, serum angiotensin converting enzyme, complement, rheumatoid factor, HLA B-27, serum VDRL, anti-cardiolipin antibodies, and a chest radiograph were normal.

The patient was treated conservatively with topical corticosteroids. Further exacerbations, resulted in bilateral ocular involvement with extensive peripheral retinal vasculitis (fig 2). Symptoms included fatigue, lethargy, arthralgia, weight loss, and loin pain. Systemic examination demonstrated finger pulp haemorrhages indicative of cutaneous vasculitis.

Figure 2.

Fundal fluorescein angiography demonstrating extensive peripheral retinal vasculitis.

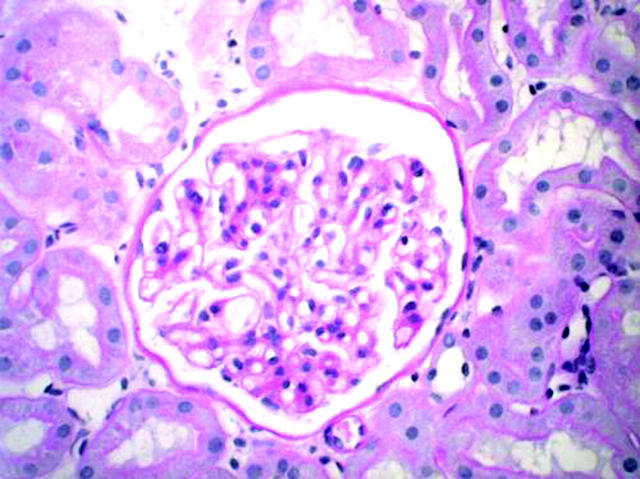

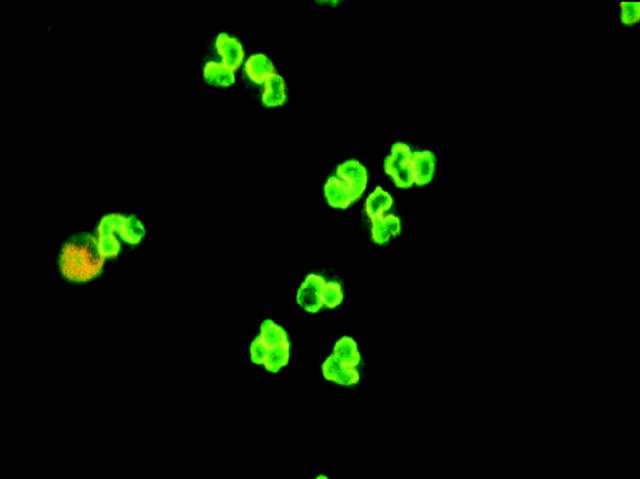

Renal ultrasound was normal. Repeat urinalysis demonstrated persistent haematuria. Serial mid-stream urine specimens were negative demonstrating no evidence of pus cells or organisms. A renal biopsy demonstrated an interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with absence of immune complex deposition indicative of glomerulonephritis (fig 3). Renal function was normal. P-ANCA was persistently positive but was negative for MPO and PR3 antibodies. Serum antinuclear antibody (ANA) was intermittently positive (low titre). Serum ANA, however, was negative when serum ANCA was at its strongest titre (1:640) suggesting that she did indeed have a positive ANCA (fig 4).

Figure 3.

Renal biopsy demonstrating interstitial lymphocytic infiltration and paucity of immune complex deposition.

Figure 4.

Slide demonstrating immunostaining positivity for serum ANCA.

The patient responded favourably to systemic steroid treatment with adjunctive cyclosporin (150 mg twice daily). Further monitoring demonstrated a decline in renal function with an isotope glomerular filtration rate of 63 ml per minute with normal serum urea and creatinine levels. Cyclosporin therapy was discontinued and mycophenolate mofetil (1 g twice daily) commenced to continue immunosuppression which has protected against further renal compromise.

Case 2

A 39 year old woman presented with a painless reduction of vision in her left eye. She related paraesthesia in both her legs over the previous few months. Blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, with normal urinalysis.

Examination of her left posterior segment demonstrated a vitreal haemorrhage with neovascularisation in the left superotemporal quadrant. The right posterior segment also demonstrated active retinal vasculitis. A vasculitic screen was performed.

Serum P-ANCA was positive with a 1:20 titre. Anti-MPO and PR3 antibodies were negative. Serum ANA was negative. Routine bloods were normal. C reactive protein was mildly elevated at 21 mg/l, with a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Computed tomography (CT), brain, and electroencephalogram (EEG) measurements were normal. There were no other neurological symptoms to suggest multiple sclerosis. A clinical diagnosis of presumed mononeuritis multiplex was made with no cause elucidated.

She underwent a sectoral panretinal photocoagulation and was commenced on cyclosporin therapy (100 mg twice daily) to which she responded well with quiescence of her retinal vasculitis.

Case 3

A 28 year old woman presented with a reduction in vision in her left eye. Blood pressure was 115/84 mm Hg with normal urinalysis.

Examination demonstrated a left visual acuity of hand movements, a quiet anterior chamber with evidence of posterior segment vitreal haemorrhage. On resolution of the vitreal haemorrhage over a 7 week period, further re-examination demonstrated vitreal cells++ with peripheral retinal vasculitis and a localised area of neovascularisation inferiorly. Investigation of this patient’s retinal vasculitis demonstrated a positive P-ANCA (1:160) on immunofluorescence, which was negative for anti-MPO and PR3 antibodies. Serum ANA was negative. Routine bloods and renal function were normal.

This patient presented with pauci-immune retinal vasculitis without systemic involvement. She was commenced on cyclosporin (125 mg twice daily) (patient was reluctant to commence steroid treatment) and responded well, with quiescence of the vasculitis, an improvement in visual acuity to 6/9 left eye, with no further episodes of vitreal haemorrhage.

DISCUSSION

These cases represent a spectrum of clinical features associated with retinal vasculitis. The first case presented with a chronic history of arthralgia, followed by systemic features of fatigue, lethargy, weight loss, mononeuritis multiplex, finger pulp haemorrhages, and loin pain.

Our patient developed a progressive deterioration in glomerular filtration rate, indicative of intrinsic renal disease. No immune complex deposition was seen on renal biopsy. In conjunction with a positive P-ANCA and in the absence of granulomatous inflammation or the presence of eosinoplilia or asthma in this patient, a diagnosis of microscopic polyangiitis was made.

It is highly probable that our second case is also a case of evolving MPA (according to the international consensus statement) presenting with bilateral retinal vasculitis and peripheral neuropathy in association with a positive P-ANCA. Our third P-ANCA positive retinal vasculitis case continues to be screened for associated systemic features. Our paper describes three cases of retinal vasculitis, all with positive serum P-ANCA, two of which have evolved into clinically recognisable entities as MPA. Jennette et al suggest that patients who initially have clinical manifestations consistent with MPA may subsequently develop features of Wegener’s granulomatosis.4

These patients presented with retinal vasculitis in association with a positive P-ANCA on immunofluorescence, negative for anti-MPO and PR3 antibodies. Despite the absence of either MPO or PR3 antibodies two of our patients showed evidence of systemic vasculitic involvement. We suggest that any patient with P-ANCA positivity (by ELISA or indirect immunofluorescence) and retinal vasculitis, regardless of specificity should be reviewed for evidence of systemic vasculitis. When systemic clinical features are present the demonstration of ANCA is probably 95% sensitive and 90% specific for these diseases and has a much higher positive predictive value than in other hospitalised patients.5

In an attempt to clarify the testing and reporting of ANCA serology, an international consensus statement was formulated. The consensus recommends testing for ANCA in patients with:

glomerulonephritis

pulmonary haemorrhage

cutaneous vasculitis with systemic features

mononeuritis multiplex or other peripheral neuropathy

longstanding sinusitis or otitis

subglottic tracheal stenosis

retro-orbital mass.

The presence of one of these clinical features, or other strong clinical evidence for small vessel vasculitis with a positive ANCA test provides 90% confirmation of pauci-immune small vessel vasculitides.3 The antigen specificity of ANCA points towards different clinicopathological phenotypes of the small vessel pauci-immune vasculitides. A negative result does not rule out this category of vasculitides (table 1).4

Table 1.

Serum ANCA specificity in untreated disease

| PR3-ANCA | MPO-ANCA | Negative | |

| Microscopic polyangiitis | 40% | 50% | 10% |

| Wegener’s granulomatosis | 75% | 20% | 5% |

| Churg-Strauss syndrome | 10% | 60% | 30% |

Adapted from Jennette et al.4

Microscopic polyangiitis is a now recognised pauci-immune systemic vasculitis. Small vessel involvement is the definitive diagnostic criterion of MPA and excludes the diagnosis of polyarteritis nodosa even if medium sized arterial lesions are also seen. MPA has an incidence of approximately 1:100 000 with a slight female predominance, a mean age of onset of 50 years, although any age may be affected.4 Guillevin et al6 have described the clinical features in 85 patients (table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical manifestations of microscopic polyangiitis

| Renal manifestations | 78.8% |

| Weight loss | 72.9% |

| Skin involvement | 62.4% |

| Fever | 53.3% |

| Mononeuritis multiplex | 57.6% |

| Athralgia | 50.6% |

| Myalgia | 48.2% |

| Hypertension | 34.1% |

| Gastrointestinal involvement | 30.6% |

| Pulmonary involvement | 24.7% |

| Central nervous system Involvement | 11.8% |

| Digital ischaemia | 7.1% |

| Ocular involvement | 1.2% |

Percentages reflecting the frequency of involvement in a study group of 85 patients positive for microscopic polyangiitis. Adapted from Guillevin et al.6

The pathophysiological relevance of ANCA has been studied extensively. It has been demonstrated7 that IgG fractions from ANCA positive sera, are capable of inducing tumour necrosis factor primed neutrophils to release lysosomal enzymes and produce reactive oxygen species inducing vascular injury. ANCA associated vasculitides are described as being pauci-immune, characterised by necrotising inflammation but with a paucity of immune deposits.8

The recommended treatment for MPA is high dose corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide.9 Dandekar et al, in their recent series on ocular involvement in systemic vasculitis, relate that treatment with immunosuppressants resulted in a reduction in P-ANCA titre with dramatic improvement of symptoms.10

In conclusion, we advocate the testing of all patients with retinal vasculitis for serum ANCA. We acknowledge that ANCA specificity does not allow us to distinguish diverse forms of necrotising vasculitis. We speculate that the incidence of MPA may be underestimated because of the under-recognition of systemic involvement in patients with retinal vasculitis. We emphasise the importance in this regard of recognition of these clinical features and the differential diagnosis of these pauci-immune small vessel vasculitides so that prompt immunosuppressive therapy is instituted and patient morbidity, if not mortality, is prevented.

Acknowledgments

We thank the library staff and Medical Illustration Department at Gartnavel General Hospital, Glasgow.

Abbreviations

ANA, antinuclear antibody

ANCA, antinuclear cytoplasmic antibodies

MPO, myeloperoxidase

REFERENCES

- 1.Falk RJ, Jennette JC. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies with specificity for myeloperoxidase in patients with systemic vasculitis and idiopathic necrotising and crescentic glomerulonephritis. N Engl J Med 1998;318:1651–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niles JL, McCluskey RT, Ahmed MF, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis autoantigen is a novel neutrophil serine proteinase. Blood 1989;74:1888–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savige J, Gillis D, Davies D, et al. International consensus statement on testing and reporting of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Am J Clin Pathol 1999;111:507–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jennette JC, Thomas BD, Falk RJ. Microscopic Polyangiitis. Sem Diagn Pathol 2001;18:1:3–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jennette JC. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated diseases; a pathologist’s perspective. Am J Kidney Dis 1991;28:164–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guillevin L, Durand-Gasselin B, Cevallos R, et al. Microscopic polyangiitis: clinical and laboratory findings in eighty-five patients. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:3:421–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falk R, Terrell R, Charles L, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies induce neutrophils to degranulate and produce oxygen radicals in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990;87:4115–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harper L, Savage CO. Pathogenesis of ANCA-associated systemic vasculitis. J Pathol 2000;190:349–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guillevin L, Lhote F. Distinguishing polyarteritis nodosa from microscopic polyangiitis and implications for treatment. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1995;7:20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dandekar SS, Narendran NN, Edmunds B, et al. Ocular involvement in systemic vasculitis associated with perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:786–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]