Congenital upper eyelid eversion is a rare condition more frequently seen in black infants and in Down’s syndrome. If recognised early, the condition can be managed conservatively without recourse to surgery. We highlight a case that presented late with severe sight threatening complications. Surgical intervention was consequently the only appropriate way to manage the patient.

Case report

A 7 month old black female was referred to the emergency room of the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. She had a history of a white spot in the right cornea, and a right upper lid that had flipped up since birth.

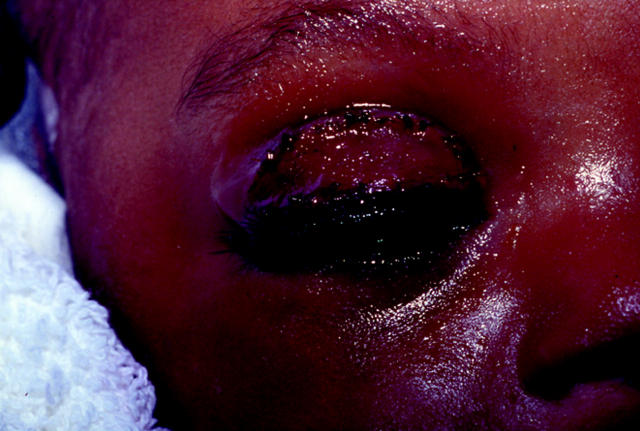

She was born by breech delivery and was subsequently diagnosed as having Down’s syndrome. On examination she had complete eversion of the right upper lid with mild conjunctival chemosis. The lid could be repositioned with ease but when the child cried it reverted. There was a corneal opacity with a central descematocele and iris adhesion to the endothelium. The child was admitted and started on intensive topical antibiotics. In spite of manual inversion of the upper lid as well as a moist chamber, the lid continued to re-evert. A lateral tarsorrhaphy and penetrating keratoplasty were performed under general anesthesia but, postoperatively, the eyelid continued to evert (fig 1). Because of the risk of exposure to the transplanted cornea, a full thickness skin graft to the right upper lid was performed (fig 2). Subsequently, the lid retained its normal position and the child could fix and follow adequately with the eye. The transplanted cornea was clear at the 10 week postoperative visit after which the patient was lost to follow up.

Figure 1.

After the tectonic penetrating keratoplasty was performed, the lateral temporal tarsorrhaphy failed to retain the lid in an inverted position.

Figure 2.

Full thickness skin graft to the upper lid successfully expanded the anterior lamella to permanently solve the problem.

Comment

Congenital eversion of the upper eyelid was first described in 1896 by Adams1 who called the condition “double congenital ectropion.” The exact incidence of this condition is not known. Sellar2 reviewed the literature in 1992 and found 51 reported cases. Since then only two more case reports could be found in the literature.3,4 The eversion is usually present at birth, but late onset of total eversion of the upper eyelids has been described in infancy,5 and as late as 11 years of age.2

The condition typically is bilateral and asymmetrical but unilateral cases have been described. The underlying pathophysiology is obscure and several possible mechanisms have been proposed and associations recognised. The incidence appears to be higher in black infants,6 infants with trisomy 21,2 and in infants born with collodion skin disease.7 Abnormalities such as orbicularis hypotonia,8 birth trauma, vertical shortening of the anterior lamellar or vertical elongation of the posterior lamellar of the eyelid and failure of the orbital septum to fuse with the levator aponeurosis (with adipose tissue interposition),9 absence of effective lateral canthal ligament, and lateral elongation of the eyelid have all been implicated as possible pathophysiological factors. Once everted, orbicularis spasm10 may act as a sphincter that leads to a vicious cycle of conjunctival strangulation and oedema secondary to venous stasis. This chemotic conjunctiva usually protects the cornea from exposure and, hence, corneal complications have thus far not been reported in infants. To our knowledge this is the first reported case of congenital eyelid eversion complicated by corneal exposure, descematocele, and perforation.

Congenital eyelid eversion either resolves spontaneously with conservative treatment or with surgical intervention such as a subconjunctival injection of hyaluronic acid, tarsorrhaphy with excision of redundant conjunctiva, fornix sutures, and full thickness skingraft to the upperlid. In this patient because of failure of all conservative measures, the chronicity (7 months) and severity (corneal ulcer/perforation), we elected to do anterior lamellar lengthening by means of a full thickness upper lid skin graft. Corneal perforation necessitating penetrating keratoplasty is a rare complication of congenital eyelid eversion, but in this case it was essential to maintain the integrity of the globe and to, hopefully, retain vision and prevent deep amblyopia.

The condition in this reported case of congenital eyelid eversion complicated by a corneal ulcer, large descematocele and perforation, is rare. Congenital upper lid eversion may present “once in a lifetime” to the ophthalmologist or newborn nursery paediatrician. It is nevertheless important to create awareness among healthcare professionals in obstetric and neonatal care of the existence of this potentially sight threatening congenital anomaly, as the condition is very amenable to early treatment.

References

- 1.Adams AL. A case of double congenital ectropion. Med Fortnightly 1896;9:137–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sellar PW, Bryars JH, Archer DB. Late presentation of congenital ectropion of the eyelids in a child with Down’s syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1992;29:64–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watts MT, Dapling RB. Congenital eversion of the upper eyelid: a case report. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1995;11:293–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawodu OA. Total eversion of the upper eyelids in a newborn. Niger Postgrad Med J 2001;8:145–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siverstone B, Hirsch I, Sternberg MD, et al. Late onset of total eversion of upper eyelids. Ann Ophthalmol 1982;14:477–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu LW, Bansal RK, Katzman B. Primary congenital eversion of the upper lids. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1979;16:149–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro RD, Soentgen ML. Collodion skin disease and everted eyelids. Postgrad Med 1969;45:216–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loeffler M, Hornblass A. Surgical management of congenital upper-eyelid eversion. Ophthalmic Surg 1990;21:736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blechman B, Isenberg S. An anatomical etiology of congenital eyelid eversion. Ophthalmic Surg 1984;15:111–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raab EL, Saphir RL. Congenital eyelid eversion with orbicularis spasm. J Pediatr Ophthal Strabismus 1985;22:125–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]