Melanocytic intraocular tumours can grow as to exceed their vascular supply, become necrotic, and induce inflammation. They present with atypical signs and become a diagnostic challenge. We present a case of a large melanocytic intraocular tumour that offered an atypical presentation, unexpected cytology, and finally diagnostic histopathology.

Case report

A 37 year old white woman presented with a painful right eye and vision loss. Exam ination showed no light perception, a relative afferent pupillary defect, a shallow anterior chamber, and an intraocular pressure of 58 mm Hg. Dense vitreous haemorrhage and tumour obscured her fundus.

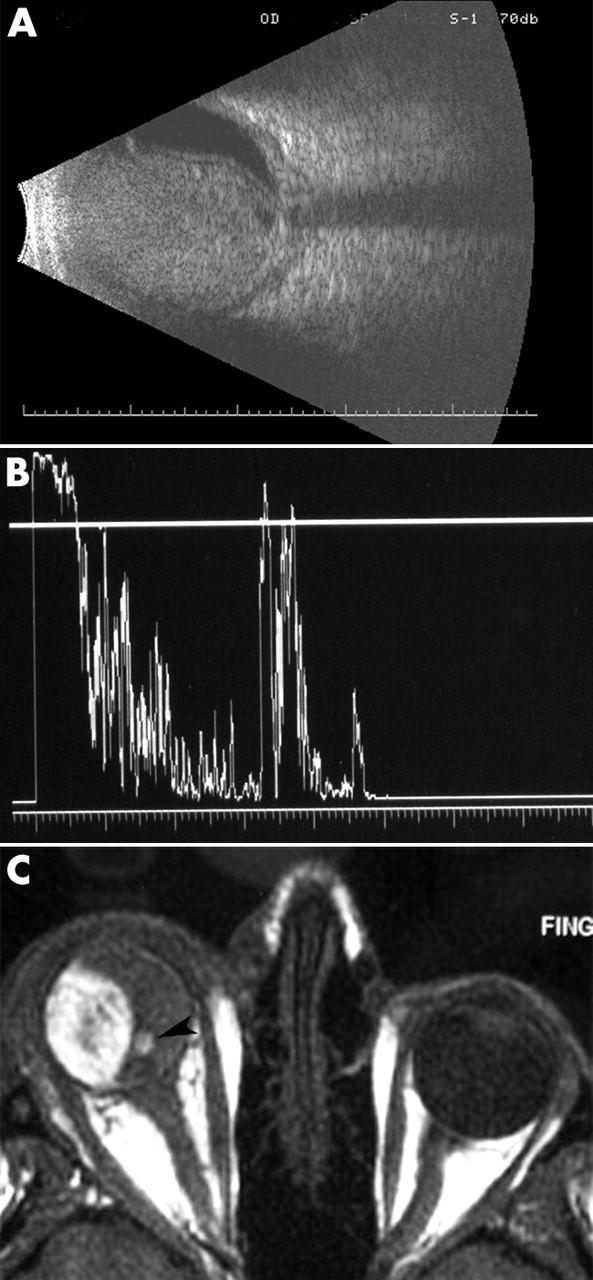

Three dimensional ultrasonography revealed vitreous haemorrhage, a total retinal detachment, and a large choroidal mass (fig 1A, B). Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbits showed a 2 cm intraocular mass with a collar-button extension (arrow) consistent with a choroidal melanoma (fig 1C).

Figure 1.

(A) B-scan ultrasound demonstrated a large intraocular tumour with scleral thickening and retrobulbar oedema. There was almost no intrinsic vascularity noted within the tumour. No extrascleral tumour extension was noted. (B) A-scan ultrasonography of the right eye showed relative low internal reflectivity. (C) MRI of the orbits was significant for an intraocular tumour that displayed high signal intensity on T1 weighted images. On T2 weighted images it displayed low signal intensity. Note the small eccentric collar-button (arrow). There was no evidence of extraocular tumour extension.

The patient participated in a discussion of the risks and benefits of treatment, found primary enucleation unacceptable, and preferred fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) before treatment.

Cytology

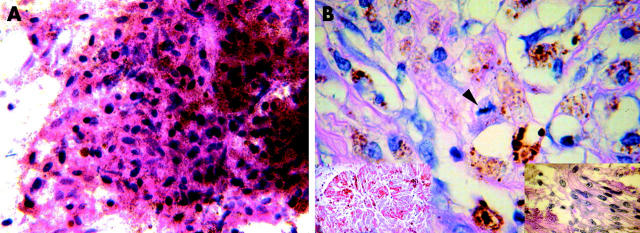

Transvitreal FNAB showed small, well preserved, spindle-shaped, dendritic, and epithelioid cells with evenly distributed melanin pigmentation (fig 2A) and no evidence of malignancy. Both cytology and subsequent immunohistochemistry were consistent with melanocytoma.

Figure 2.

(A) The cytological preparations from FNAB showed very small, pigmented dendritic and epithelioid cells with small dark oblong nuclei. No mitoses or necrosis was present. Some of the very deeply pigmented cells seen were melanophages. These cells were naevus-like, there were no cells that were large enough or that had appropriate nuclear morphology to be called melanoma (original magnification ×100). (B) Histopathology of the enucleated eye showed a necrotic tumour (left inset; original magnification ×100). Histopathology demonstrated spindle and small epithelioid melanoma cells (right inset; original magnification ×100) and a melanoma with a mitotic figure in the centre (arrow). These findings suggested malignant change (original magnification ×100).

Though a combination of topical glaucoma medications and oral prednisone decreased her ocular pain, the patient consented to enucleation.

Macroscopic examination

A large evenly pigmented choroidal mass measuring 12 mm in height and 17×18 mm in greatest dimension was noted. The tumour extended from the ciliary body to the optic disc.

Light microscopy

Extensive infarction of the tumour was present. The cell outlines revealed a tumour composed of uniform large and heavily pigmented cells with round, small central nuclei. Many of these cells were magnocellular and histopathologically consistent with melanocytoma. However, distinct cells with larger nuclei and prominent nucleoli were present singly and in small clusters. In these areas, rare atypical mitoses were noted. These features were diagnostic of malignant transformation of a large melanocytoma (fig 2B). At 6 months post-enucleation there is no evidence of metastatic disease.

Comment

Melanocytomas are darkly pigmented tumours that commonly arise at the optic nerve margin. They also occur in the iris, ciliary body, and the choroid. Though largely benign and stationary, melanocytomas can (albeit rarely) undergo malignant transformation.1–8 When this occurs, it can be difficult to differentiate between melanocytomas and malignant melanomas by ultrasonography or fluorescein angiography. Adenoma and adenocarcinoma of the retinal pigment epithelium should also be considered.

In this case, FNAB did not establish the diagnosis of a malignant melanocytoma and clearly demonstrates the potential danger of relying on FNAB (alone) for the diagnosis in atypical and necrotic intraocular tumours. Foci of malignant change were missed, leading to the diagnosis of melanocytoma. Fortunately, enucleation was performed.

This case also demonstrates that melanocytomas can undergo necrosis resulting in atypical features such as opaque media, pain and inflammation. They can induce vaso-occlusive disease within the optic nerve, ischaemic necrosis of the tumour, ischaemic retinopathy, neovascular glaucoma, and melanocytic glaucoma.9 Since both necrotic melanocytomas and necrotic malignant uveal melanomas can present with the same acute symptoms (pain, inflammation, and an elevated intraocular pressure), these findings can detract the clinician’s ability to differentiate between these tumours.

Malignant change in a melanocytoma is a rare event. It is actually more common for a uveal melanoma to undergo spontaneous necrosis and present with intraocular inflammation, haemorrhage, secondary neovascularisation, and orbital inflammation. Such necrotising tumours have an increased incidence of penetration through the Bruch’s membrane, scleral invasion, and extrascleral extension.10 Clearly, large necrotic intraocular tumours can be a diagnostic challenge for both clinician and pathologist.

This work is supported by The Eye Care Foundation, Inc, and Research to Prevent Blindness, New York City, NY, USA.

The authors have no proprietary interest in the products mentioned in this study.

References

- 1.Zimmerman LE. Melanocytic tumors of interest to the ophthalmologist. Ophthalmology 1980;87:497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reidy JJ, Apple DJ, Steinmetz RL, et al. Melanocytoma: nomenclature, pathogenesis, natural history and treatment. Surv Ophthalmol 1985;29:319–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth AM. Malignant change in melanocytomas of the uveal tract. Surv Ophthalmol 1978;22:404–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apple DJ, Craythorn JM, Reidy JJ, et al. Malignant transformation of an optic nerve melanocytoma. Can J Ophthalmol 1984;19:320–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker-Griffith AE, McDonald RP, Green WR. Malignant melanoma arising in a choroidal magnocellular nevus (melanocytoma). Can J Ophthalmol 1976;11:140–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heitman KF, Kincaid MC, Steahly L. Diffuse malignant change in a ciliochoroidal melanocytoma in a patient of mixed racial background. Retina 1988;8:67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leidinix M, Mamalis N, Goodart R, et al. Malignant transformation of a necrotic melanocytoma of the choroid in an amblyopic eye. Ann Ophthalmol 1994;26:42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shetlar DJ, Folberg R, Gass JDM. Choroidal malignant melanoma associated with a melanocytoma. Retina 1999;19:346–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teichmann KD, Karcioglu ZA. Melanocytoma of the iris with rapidly developing secondary glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol 1995;40:136–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moshari A, Cheeseman EW, McLean IW. Totally necrotic choroidal and ciliary body melanomas: associations with prognosis, episcleritis and scleritis. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131:232–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]