This report documents the occurrence in three patients of subretinal choroidal neovascular membranes (CNVM) ipsilateral to meningiomas involving the optic nerve. We propose that the association might not be coincidental.

Case 1

A 31 year old woman developed a central scotoma in the left eye that led to the diagnosis of a left sphenoid wing meningioma involving the optic canal. The tumour was resected and her vision returned to normal. At age 56 a generalised seizure led to recognition of a recurrence. When the recurrent tumour was resected it proved to be a malignant meningioma. She was then treated with photon radiation from a 10 MV source using a three field technique (right lateral, left lateral, and superior). The total dose was 45 Gy administered in 25 fractions. Thereafter, on regular follow up eye examinations she had normal visual function, pupils, and fundi. At the age of 64 she had a single episode in which for several seconds she lost all vision in the left eye except for a nasal island. There were no residua but her ophthalmologist found a new fundus abnormality that prompted referral.

Her medical history included migraine and a cutaneous malignant melanoma. There was no pertinent family history.

The patient’s visual acuities were 20/15 in each eye. Her colour vision (Ishihara) and pupils were normal. The Goldmann visual field of her right eye was full but she had a relative inferior altitudinal defect to the I2e white stimulus in the left eye. There was 3 mm of proptosis of the left eye with normal orbital resiliency. Fundus examination of the left eye revealed a peripapillary superotemporal retinal elevation associated with lipid (fig 1, top left). There were no macular drusen. Echography showed 1.1 mm of elevated retina adjacent to the left disc with normal acoustics. The rest of her neuro-ophthalmological examination was normal. There was hyperfluorescence in the area of elevation with late leakage of dye on fluorescein angiography consistent with a peripapillary CNVM (fig 1). At that time magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans showed no evidence of recurrent meningioma.

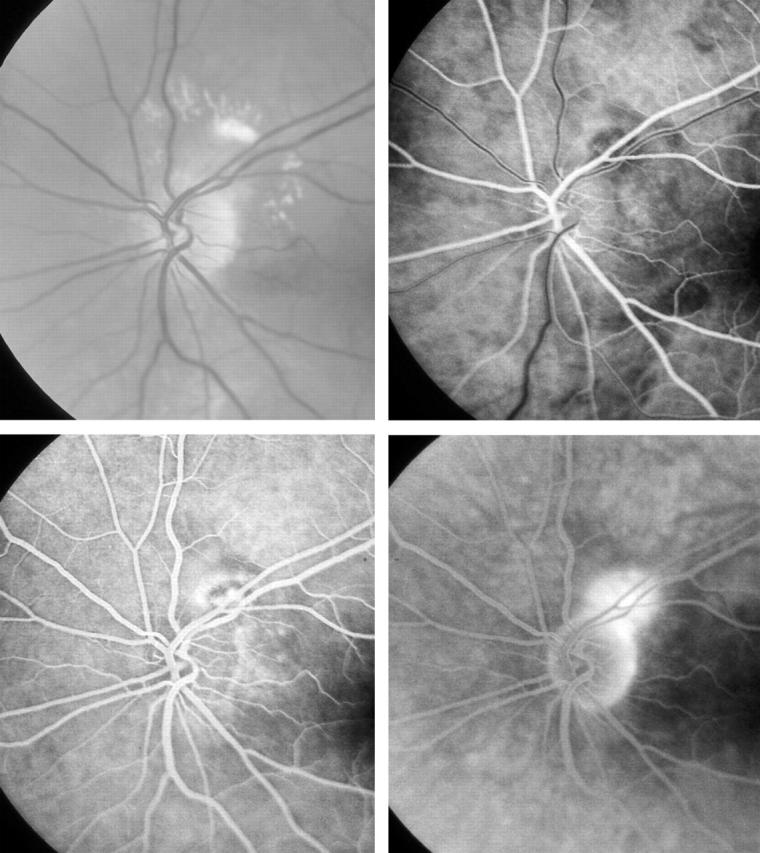

Figure 1.

Patient 1. Retinal elevation and lipid exudation superotemporal to the left optic disc (top left). Venous laminar (top right), arteriovenous transit (bottom left), and late phases (bottom right) of the fluorescein angiogram demonstrates peripapillary hyperfluorescent area growing in size and fluorescence consistent choroidal neovascularisation.

Five years later the vision declined to 20/30 in the left eye. There was neither optic atrophy nor optic disc swelling, but a left afferent pupillary defect and dyschromatopsia were observed. MRI showed that the sphenoid meningioma had recurred and involved the intracanalicular and posterior orbital segments of the left optic nerve. There also was enlargement of the posterior bellies of the left inferior and lateral rectus muscles.

Case 2

An 89 year old woman had cataract surgery on her left eye in December 2000 and her right eye in February 2001. She initially saw well following surgery; however, in August 2001 she noted blurring of the vision in her left eye and a peripapillary CNVM was discovered. Despite two laser applications the patient’s vision continued to worsen.

Her medical history included rheumatic heart disease, hypertension, and hypercholesterolaemia. In February 2001 she had endocarditis complicated by a left hemiplegia. There was no family history of any pertinent disorder.

Her visual acuities were 20/20 in the right eye and 7/200 in the left. She had dyschromatopsia of the left eye with 2 mm of proptosis and a relative afferent pupil defect. Goldmann perimetry revealed a full visual field in the right eye and only a residual nasal island in the left. The fundus of the right eye was normal without drusen. Her left optic disc was pale and there was nerve fibre layer swelling and haemorrhage adjacent to the nerve. MRI showed a 1.4×1.2×1.2 cm homogeneously enhancing mass along the left planum sphenoidale extending into the left optic canal consistent with a meningioma.

Case 3

A 47 year old woman noticed that she had a painless visual disturbance of her right eye “like looking through a glass of water.” The symptom persisted, and 2 months later she awoke with a blind right eye. An MRI scan was interpreted as normal and her blindness was ascribed to optic neuritis. She was treated with a course of corticosteroids during which she recovered some vision but her vision failed again after the steroids were discontinued and thereafter she was unable to see light.

She had a history of asthma and obesity. Her father had age related macular degeneration.

At the age of 49 she noticed metamorphopsia in the left eye, and a large, elevated, extrafoveal CNVM was found. Echography revealed 1.3 mm of elevation, which was acoustically normal. Vision was then 20/20. The right optic disc was atrophic and the left was normal. There were no macular drusen. She failed to respond to laser photocoagulation and proton beam radiation. Vision failed to 3/200 and the left disc became oedematous. MRI scanning showed bilateral optic nerve sheath enlargement and gadolinium enhancement of the mid and posterior segments of both optic nerves and extension of the lesion on the right side over the planum towards the chiasm. The lesions were interpreted as primary optic nerve sheath meningiomas.

Comment

Choroidal neovascularisation has been associated with macular degeneration, histoplasmosis, pathological myopia, angioid streaks, optic nerve drusen, optic nerve pits, pseudotumour cerebri, chronic inflammation, infection, malignant melanoma, choroidal osteomas, choroidal naevi, photocoagulation, and choroidal rupture. A break in Bruch’s membrane seems to be a common feature in CNV, but the exact pathogenesis remains a subject of debate.1,2

While we cannot eliminate the possibility that the association of CNV with meningiomas and CNV in our patients is merely by chance, several observations suggest otherwise. In each case the fundus of the fellow eye was free of drusen, let alone more substantive evidence of macular degeneration. None of the patients had a disorder known to predispose to CNV. There has been one report of CNV after radiation but in that case the patient also had significant radiation retinopathy.3 Our irradiated patient (case 1) had no evidence of radiation retinopathy and the radiation portals spared the eye. One of our patients was only 49 years old when the membrane was recognised. In two of our patients the membrane was peripapillary.

Schatz et al published the histopathological findings in a patient with a primary optic nerve sheath meningioma in which there was a CNV. However, their patient had chronic disc oedema and venous collaterals and had antecedent age related macular degeneration in both eyes.4 Shields et al described an instance of CNV in a child with an optic nerve glioma. That patient’s disc was also oedematous.5 Peripapillary CNV has been described with chronic disc oedema of other causes as well,6 but two of our patients never had disc swelling and the third developed disc oedema only after the CNV was recognised.

How might a meningioma cause an ipsilateral CNV? The pathophysiological mechanism by which these two conditions occur together is unclear. It is possible that the tumour tissue could have invaded the eye. CNV has been associated with other tumours involving the choroid.1,2 Ocular invasion was not evident on ultrasound (cases 1 and 3) or MRI scans but absence of proof is not proof of absence. In the case of Schatz et al there were small foci of the meningioma in the peripapillary sclera and retrolaminar optic nerve, which were not seen before enucleation.4 Dutton reviewed meningiomas involving the optic nerve and primary optic nerve sheath meningiomas. CNV was not mentioned as a presenting sign. None the less, he calculated 3.7% of 477 reported cases described intraocular invasion by meningiomas.7 Other authors have reported histopathological cases of meningioma invading the optic nerve and disc.8,9,10

We believe that the association of CNV with ipsilateral meningiomas in our patients was not one of chance. The presumed mechanism is invasion of the globe by the tumour sufficient to cause the CNV but below threshold for detection by MRI, ultrasound, or ophthalmoscopy.

Supported by the Heed Foundation, Cleveland, OH, USA (MSL).

Competing interests: none declared

Presented in part at the North American Neuro-ophthalmology Society annual meeting, Snowbird, UT, USA, February 2003.

References

- 1.Green WR, Wilson DJ. Choroidal neovascularization. Ophthalmology 1986;93:1169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez FP, Green WR. Peripapillary subretinal neovascularization: a review. Retina 1992;12:147–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spaide RF, Borodoker N, Shah V. Atypical choroidal neovascularization in radiation retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;133:709–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schatz H, Green WR, Talamo JH, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of retinal to choroidal venous collaterals of the optic nerve head. Ophthalmology 1991;98:1287–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shields JA, Shields CL, De Potter P, et al. Choroidal neovascular membrane as a feature of optic nerve glioma. Retina 1997;17:349–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamison RR. Subretinal neovascularization and papilledema associated with pseudotumor cerebri. Am J Ophthalmol 1978;85:78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutton JJ. Optic nerve sheath meningiomas. Surv Ophthalmol 1992;37:167–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodrigues MM, Savino PJ, Schatz NJ. Spheno-orbital meningioma with optociliary veins. Am J Ophthalmol 1976;81:666–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coston TO. Primary tumor of the optic nerve: with report of a case. Arch Ophthalmol 1936;15:696–702. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunn SN, Walsh FB. Meningioma (dural endothelioma) of the optic nerve. Arch Ophthalmol 1956;56:702–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]