Cystinosis is an autosomal recessive inherited disorder of amino acid metabolism characterised by the deposition of cystine crystals in the eye, kidney, reticuloendothelial system, and various other tissues.1 Childhood or nephropathic cystinosis can present as an infantile or a juvenile variant.1 The infantile variant tends to have a more devastating course and is associated with growth retardation, rickets, and eventual renal failure which requires transplantation within the first decade.1 The juvenile variant has later onset and milder nephropathy.1

In nephropathic cystinosis, crystal deposits usually appear in the peripheral, anterior cornea within the first year of life and progress centrally and posteriorly until the entire cornea is involved.2–7 The diagnosis can be confirmed histopathologically by demonstration of characteristic crystals by electron microscopy in a conjunctival biopsy.8,9 Stromal deposition of crystal deposits has been demonstrated by confocal microscopy.9 We provide the first demonstration, to the best of our knowledge, of cystine crystals in the corneal epithelium using in vivo confocal microscopy.

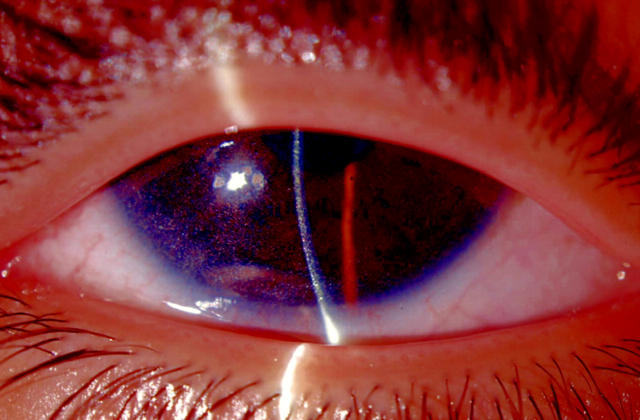

Case report

A 9 year old boy presented to the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, with a complaint of recurrent foreign body sensation, associated with severe photophobia and blepharospasm. He had been diagnosed with infantile nephropathic cystinosis at age of 9 months and had been treated with systemic cysteamine. On examination, the visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye. The intraocular pressure was 12 mm Hg in both eyes. Slit lamp examination showed crystal deposits of 2.5 in Gahl density score7 in both corneas, predominantly involving the anterior stroma and with limbus to limbus distribution (fig 1). Dilated fundus examination was normal with no maculopathy or peripheral retinal pigment abnormalities. Topical treatment with cysteamine 0.5% drops resulted in symptomatic relief.

Figure 1.

Crystal deposits in the right eye predominantly involving the anterior and mid-stroma, with limbus to limbus distribution.

Confocal microscopy (Confoscan 3, Nidek Technologies, Vigonza, Italy) demonstrated crystalline deposits in the corneal epithelium (fig 2A, B) and stroma (fig 2C, D). Crystal deposits in the corneal epithelium were needle shaped and fusiform shaped and oriented parallel to the plane of the epithelial cells (fig 2A, B). In the basal cell layer, the crystals were associated with dendritic cells (fig 2B). The highest crystal density was in the mid-stroma, where fusiform shaped crystals were more predominant than needle shaped crystals (fig 2C). The lowest crystal density was in the posterior stroma, where most of the deposits were needle shaped (fig 2E). Within the stroma the crystals were oriented parallel to the plane of the stromal lamella. The needle shaped crystals were highly variable in length with some as long as 100 µm. The endothelial cell layer was normal.

Figure 2.

Crystal deposits in the corneal epithelium and stroma. A mixture of needle shaped and fusiform shaped crystals are present in (A) the superficial epithelial cell layer and (B) the wing cell layer. (C) Dendritic cells are present in the basal cell layer. (D) The greatest density of crystals is in the mid-stroma, where fusiform shaped crystals are the predominant morphology. (E) The least density of crystals is in the posterior stroma, where needle shaped crystals are the predominant morphology.

Comment

The current case clearly documents that crystalline deposits may be found in the epithelium of patients with nephropathic cystinosis, unlike previous electron microscopic8 and confocal microscopic9 studies that suggest these deposits are localised to the stroma. In addition, we found maximum crystal density in the mid-stroma and minimum density in the posterior stroma, in contrast with a previous report in which maximum crystal density was just anterior to Descemet’s membrane.9

We hypothesise the presence of these abnormal deposits in the corneal epithelium may contribute, in part, to the foreign body sensation and photophobia that is invariably associated with this disorder, as well as the predisposition to recurrent epithelial erosions. Chronic low grade inflammation of the epithelium and epithelial basement membrane zone associated with recurrent epithelial erosions is the probable explanation for the presence of dendritic cells in the basal epithelium of the central cornea.10 Successful reduction in the density of corneal crystals and symptomatic relief was obtained with the use of topical cysteamine 0.5% drops, as in previous reports.5–7

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Theone JG. Cystinosis. J Inherit Metab Dis 1995;18:380–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong VG, Schulman JD, Seegmiller JE. Conjunctival biopsy for the biochemical diagnosis of cystinosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1970;70:278–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Chan CC, Rodriques M, et al. Nephropathic cystinosis: immunohistochemical and histopathologic studies of cornea, conjunctiva, and iris. Curr Eye Res 1987;66:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cotran PR, Bajart AM. Congenital corneal opacities. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1992;32:93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwata F, Kuehl EM, Reed GF, et al. A randomized clinical trial of topical cysteamine disulfide (cystamine) versus free thiol (cysteamine) in the treatment of corneal cystine crystals in cystinosis. Mol Genet Metab 1998;64:237–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gahl WA, Kuehl EM, Iwata F, et al. Corneal crystals in nephropathic cystinosis: natural history and treatment with cysteamine eyedrops. Mol Genet Metab 2000;71:100–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan AO, Latimer B. Successful use of topical cysteamine formulated from the oral preparation in a child with keratopathy secondary to cystinosis. Am J Ophthalmol 2004;138:674–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenyon KR, Sensenbrenner JA. Electron microscopy of cornea and conjunctiva in childhood cystinosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1974;78:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grupcheva CN, Ormonde SE, McGhee C. In vivo confocal microscopy of the cornea in nephropathic cystinosis. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:1742–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillette TE, Chandler JW, Greiner JV. Langerhans cells of the ocular surface. Ophthalmology 1982;89:700–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]