Abstract

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN), with the absence of enteral nutrition, results in profound changes to both intestinal epithelial cells (EC) as well as the adjacent intraepithelial lymphocyte (IEL) population. Intestinal EC are a rich source of IL-7, a critical factor to support the maintenance of several lymphoid tissues, and TPN results in marked EC changes. Based on this, we hypothesized that TPN would diminish EC-derived IL-7 expression, and this would contribute to the observed changes in the IEL population. Mice received enteral food and intravenous crystalloid solution (Control group) or TPN. TPN administration significantly decreased EC-derived IL-7 expression, along with significant changes in IEL phenotype, decreased IEL proliferation and resulted in a marked decrease in IEL numbers. To better determine the relevance of TPN related changes in IL-7, TPN mice supplemented with exogenous IL-7, or mice allowed ad lib feeding and treated with exogenous administration of anti-IL-7 receptor (IL-7R) antibody (Ab) were also studied. Exogenous IL-7 administration in TPN mice significantly attenuated TPN-associated IEL changes. Whereas, blocking IL-7R in normal mice resulted in several similar changes in IEL as those observed with TPN. These findings suggest that a decrease in EC-derived IL-7 expression may be a contributing mechanism to account for the observed TPN-associated IEL changes.

Keywords: Cytokines, Intraepithelial lymphocyte, Interleukin-7, Mouse, Mucosa

INTRODUCTION

Interleukin 7 (IL-7) is a member of the gamma chain-dependent (γc) family of cytokines, which share a common receptor γc component, and include IL-2, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-15. These cytokines influence T cell development and function (12, 36). IL-7 has a major effect on the phenotype and development of thymocytes as well as other lymphoid tissues (26, 35). In vivo only IL-7, and not other γc family members (e.g., IL-4 or IL-15), was found to be essential for homeostatic proliferation of naive peripheral T cells (34). IL-7 is produced by thymic and intestinal epithelial cells (EC) (9, 35, 37); and in turn IL-7 receptors (IL-7R) have been detected on the surface of thymocytes and intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) (32, 35). Additionally, IL-7 receptors have been identified on peripheral T cells, B lineage cells and colonic lamina propria lymphocytes (32, 35). Administration of IL-7 has been demonstrated to enhance both peripheral T-cells and IEL numbers, and increase peripheral T cell and IEL function (9, 46).

Interactions between mucosal lymphocytes and intestinal EC are thought to be crucial for maintaining mucosal immunity. Several studies have indicated that EC may play an important role in mucosal immune responses by helping to regulate IEL phenotype and function (11, 35). IEL are a distinct population of T-lymphocytes that reside above the basement membrane and lie between EC. IEL act as the initial lymphoid defense layer against intraluminal foreign antigens (7), and may be of critical importance for proper functioning of the mucosal immune system (35). Previous studies by our group have shown that IEL play an important role in the maintenance of the gut barrier function and support intestinal EC growth (42–45, 47). There is an average of 10 –20 IEL per 100 villi EC in human small intestine (11). This inter-relation is well demonstrated with IL-7. IL-7 knockout and IL-7R knockout mice show distinct declines in absolute numbers of thymocytes and in the intestine, IEL (24). In an IEL culture model, IL-7 supplemented media significantly prevented the spontaneous apoptosis of IEL by decreasing caspase activity and preventing the decline in Bcl-2 expression (40).

It is estimated that total parenteral nutrition (TPN), or the intravenous administration of nutrition is essential for the sustenance; and over 550,000 patients receive TPN in the United States on a yearly basis (1). Despite this, TPN administration results in a number of immunologic problems including an increase in systemic sepsis, perioperative infections. Many of these infections may well be due to aberrancies in the mucosal immune defense system, including marked changes in the number and function of mucosal lymphocytes, including IEL (16, 17, 42, 49). It is unknown what mechanism(s) lead to these TPN-associated IEL changes. Recently, we have shown that IL-7 administration in healthy wild-type mice led to significant changes in IEL phenotype and function; including an increase in the CD8αβ+ and mature (CD44+) IEL sub-populations. IL-7 administration also significantly changed IEL-derived cytokine expression (46). Furthermore, we also demonstrated a close physical communication between EC-derived IL-7 and IEL in a mouse model (46). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that TPN-induced mucosal changes will lead to a decline in EC-derived IL-7 expression; and this decline would be responsible for changes in the neighboring IEL phenotype and function. Additionally, we hypothesized that exogenous administration of IL-7 would prevent many of the observed TPN-induced changes to the IEL.

METHODS

Animals

Studies reported here conformed to the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals established by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals at the University of Michigan, and protocols were approved by that committee (UCUCA number 7703). Male, two month old (weighing 24 to 26 grams), specific pathogen free, adult C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories, ME) were maintained in temperature, humidity and light-controlled conditions. During administration of intravenous solutions, mice were housed in metabolic cages.

Total Parenteral Nutrition Model

Administration of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) was performed as previously described (17). Mice were infused with a crystalloid solution at 4 ml/day. After 24 hrs, mice were randomized into two groups (n=6 per group). The control group received the same intravenous saline solution at 7 ml/24 hrs, in addition to standard laboratory mouse chow and water ad libitum. The TPN groups received an intravenous TPN solution at 7 ml/24 hrs. The TPN solution has been described in detail previously (17), and contained a balanced mixture of amino acids, lipids, and dextrose in addition to electrolytes, trace elements, and vitamins. Caloric delivery was based on estimates of caloric intake by the control group and from previous investigators (23), so that caloric delivery was essentially the same in both groups. All animals were sacrificed at 7 days using CO2.

Exogenous IL-7 administration

To further assess the role of IL-7 during TPN administration, IL-7 (Recombinant IL-7, R&D Systems, Inc., MN) was given to a separate group of TPN mice (TPN+IL-7 group). Mice received an intravenous injection (500 ng twice daily, (3) starting with the first day of TPN, and treatment continued for 7 days.

IL-7 in vivo Blocking

To assess the role of a decline in IL-7 on the observed altered IEL phenotype and function with TPN, in vivo blockade of IL-7 action was performed in another group of mice. This group was permitted ad lib enteral nutrition (IL-7R blocking group) and received anti-IL-7R antibody via intraperitoneal injection, as previously described (32). The control group received a non-specific, isotype IgG at the same dose. The IEL has a slow rate of lymphocyte turnover. Therefore, to allow for a complete assessment of the effect of removing IL-7 on the IEL, anti-IL-7R antibody was administered at a dose of 1 mg of immunoglobulin (IgG) per injection once every three days for a total of 4 weeks (21). All IL-7R dependent processes have been shown to be blocked by this anti-IL-7R antibody, which was generated from the hybridoma line A7R34 (kindly provided by Dr. Nishikawa Shinichi, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan). Ascites fluid was generated in nude mice and anti-IL-7R antibody was purified by using a Prosep®-G Kit (Millipore Corporation, MA, USA).

IEL Isolation and Purification

IEL isolation from small intestine

Small bowel IEL and ECs were isolated as previously described (17). Briefly, the small bowel was placed in tissue culture medium (RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS; Life Technologies, MD). Mesenteric fat and Peyer’s patches were removed. The intestine was then opened longitudinally and agitated to remove mucus and fecal material. The intestine was then cut into 5-mm pieces, washed three times in an IEL extraction buffer (l mM EDTA, l mM DTT in PBS), and incubated in the same buffer with continuous brisk stirring at 37°C for 20 min. The supernatant was then filtered rapidly through a glass wool column. Magnetic beads conjugated with antibody to CD45 (lymphocyte specific) were used to remove non-epithelial cells (BioMag SelectaPure Anti-Mouse CD 45R Antibody Particles, Polyscience Inc, Warrington, PA). Cells bound to beads were considered purified IEL; the EC remained in the supernatant. Flow cytometry confirmed purity of sorted IEL, which was greater than 99%, based on a control sample stained with anti-CD45 antibody.

Purification of IEL sub-populations

IEL sub-populations were purified by flow cytometry with cell sorting using an EPICS Elite (Coulter, Florida) cytometer, as described previously (42). The following antibodies were used for isolation of specific IEL subpopulations (CD4, CD8αβ, CD8αα, TCR-αβ, and TCR-γδ, PharMingen). Isotype-matched, irrelevant antibodies were used as a negative control.

Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction

Isolation of total RNA.

A guanidinium isothiocyanate–chloroform extraction method was used. Total RNA from isolated EC or IEL, or subtype IEL, was extracted using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Inc., MD) according to the manufacturer’s directions.

Reverse Transcriptase (RT) and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR).

poly-A tailed mRNA was reversed transcribed into complementary DNA by adding total cellular RNA to the following reaction mixture: PCR Nucleotide Mix (Invitrogen, CA), M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen), Oligo(dT)12–18 Primer (Invitrogen), and RNAse Inhibitor (40 U/μl, Roche Diagnostics, Germany). DEPC-treated H2O was added to yield the appropriate final concentration. Samples were incubated at 40°C for 70 min, and the reaction was then stopped by incubating at 95°C for 3 min. PCR reaction was run using thermal cycler settings which were optimized to insure products were in the logarithmic phase of production. PCR products were run out on a 2% agarose gel. Quantification of cDNA product was completed using a Kodak 1D image quantification software (Kodak Co, NY), and target PCR products were compared by normalizing each sample to the production of β-actin.

Real-time PCR.

A Smart Cycler thermal cycler (Cepheid Corp., Sunnyvale, CA) was used for quantification of the IL-7 mRNA expression study, For this, a mastermix of the reaction components was prepared as described previously (42). The following experimental protocol was used: denaturation program (95°C for 2 min), amplification and quantification program repeated 43 times (95°C for 15 s, 66°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 40 s). Specificity of real-time PCR products was documented with gel electrophoresis. Additionally, cDNA was extracted using a centrifugal filter device (Millipore, MA), and sequencing of this product showed that it matched the IL-7 GenBank NM_008371 mRNA sequence. The number of cDNA copies was then calculated using the gene sequence size of each gene amplicon. Serial dilutions of the amplified gene at known concentrations were tested to make a standard curve. Standard curve extrapolation of gene copy number was performed for the IL-7 gene as well as for β-actin. Normalization of values was performed by dividing the number of copies of the IL-7 gene by the number of copies of β-actin. Ratio results are multiplied by 10−5

Immunoblot Analysis for EC-derived IL-7 Expression

Briefly, isolated EC were homogenized on ice in lysis buffer (39). Protein determination was performed using a Micro BCA™ Protein Assay Kit (PIERCE, Rockford, IL). Approximately 60 μg of total protein in loading buffer was loaded per lane in a SDS-polyacrylamide-gel (13%), and separated using electrophoresis. Proteins were then transferred to a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA). The membrane was blocked with blocking solution (Zymed Laboratories Inc, CA), and probed with goat anti-mouse biotinylated-IL-7 antibody (R&D Systems, Inc. MN) (0.15 μg/ml in blocking solution) for 1 hour. Bound antibodies were exposed to a Strepavidin-HRP conjugate (1:10000, Zymed Laboratories Inc. (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), detected on X-ray film. Within a range of 37 kDa no additional bands were detected. A further confirmation of the antibody specificity was performed by the use of recombinant mouse IL-7 (R&D System, MN) as a positive control. Blots were then stripped and re-probed with monoclonal mouse anti β-actin antibody (1:8000 in blocking solution; Sigma, St Louis, MO) to confirm equal loading of protein. The peroxidase-conjugated second antibody was goat anti-mouse IgG (1:8000 in blocking solution; Invitrogen). Quantification of results was performed using Kodak 1D image quantification software (Kodak Co, NY). Thus, results of immunoblots are expressed as the relative expression of IL-7 to beta actin expression.

Flow Cytometric Analysis

IEL Phenotype analysis

IEL phenotype was studied with flow cytometry. To examine the IEL subsets, the following monoclonal antibodies (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) were used: anti-CD4, CD8α, CD8β, αβ-TCR- and γδ-TCR, as well as to CD44. Anti-mouse IL-7 receptor alpha antibody (Clone A7R34) was purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Acquisition and analysis were performed on a FACSCalibur (Becton-Dickinson, CA) using CellQuest software (Becton-Dickinson). The IEL population was gated based on forward and side scatter characteristics. Quantification of each IEL subpopulation was based on its percentage of the gated IEL population.

IEL cell cycle analysis

The modified protocol of Geiselhart, et al (9) was used. Briefly, purified IEL were permeabilized by resuspension in saponin buffer for 10 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was decanted and the pellet was resuspended in a saponin buffer containing propidium iodide (Sigma, MO) and RNase (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, IN) followed by incubation for 15 min at 4°C. Labeled cells were analyzed with flow cytometry and CellQuest software was used for cell cycle analysis. Cells in the either S phase or G2/M were considered proliferating, and were expressed as a percent of all gated IEL.

Data analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Cytokine expression and flow cytometric results were analyzed using ANOVA, and a Bonferoni post hoc analysis was used to detect differences between groups. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

RESULTS

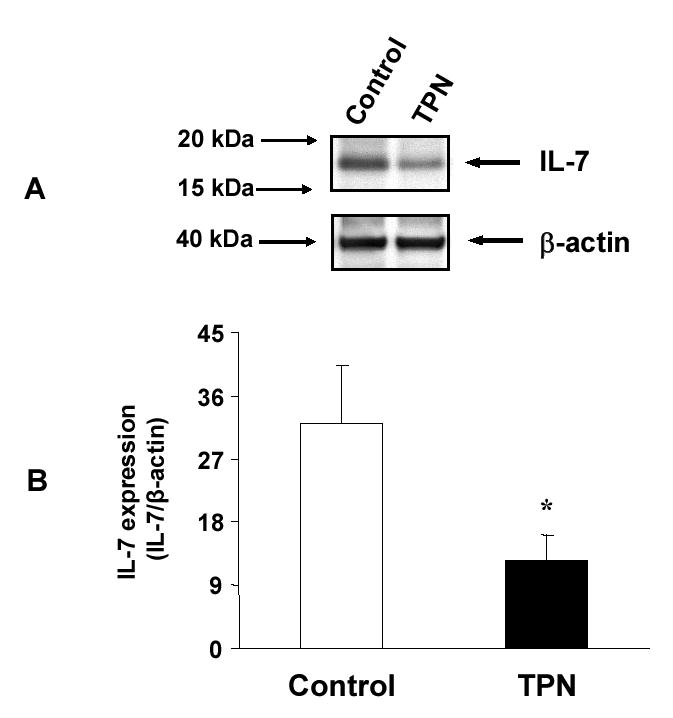

Changes in EC-derived IL-7 expression after TPN

It has been shown that IL-7 is produced by intestinal EC (4, 9, 35, 37), and plays an important role in mucosal immune responses by regulation of growth and function of IEL (11, 35). Our laboratory has previously reported that TPN administration was associated with a significant decline in the rate of EC proliferation and a rise in EC apoptosis (43, 48). We first assessed if TPN was associated changes the expression of intestinal EC-derived IL-7. Real-time PCR results showed that EC-derived IL-7 mRNA expression significantly decreased after TPN administration when compared with controls (Figure 1). Western immunoblot studies of EC-derived IL-7 protein confirmed these changes. TPN administration led to a significant decrease in EC-derived IL-7 protein expression (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Changes in EC-derived IL-7 mRNA expression in intestinal mucosal specimens. Results are measured by real-time PCR, and are expressed as the ratio of the number of copies of the IL-7 gene to the number of copies of the β-actin gene multiplied by 10−5; n =6 per group. TPN administration led to a significant decrease in EC-derived IL-7 mRNA expression compared with controls *P<0.05.

Figure 2.

Western immunoblot expression of IL-7 from isolated EC is shown. A. Composite representative immunoblot of EC-derived IL-7 expression in control and total parenteral nutrition (TPN) mice. B. TPN administration resulted in a significant decrease in EC-derived IL-7 expression. Results are the relative expression of IL-7 protein normalized to the expression of β-actin multiplied by 100; n =6 per group, *P<0.05 TPN compared to control group.

Changes in intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) after TPN administration

Changes in IEL phenotype and number

Several changes were identified in IEL surface phenotypic markers with TPN administration. These changes included a 2.5-fold decline in the CD8αβ+ IEL subpopulation (i.e., CD8αβ heterodimeric portion of the CD8+ cells) (Figure 3). Additional changes included a marked decline in the maturity of IEL, as indicated by a decline in CD44+ IEL; and consisted of a 3.6-fold decline in CD8+CD44+ IEL, and a 3.2-fold decline in CD4+CD44+ IEL (Figure 4). The CD4+ population is known to be very responsive to exogenous stimulation (16). After 7 days of TPN administration, both the CD4+CD8− as well as CD4+CD8+ IEL sub-populations decreased by 87% and 80%, respectively, when compared with controls (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Representative flow cytometry results of gated IEL populations. Cell populations are expressed as the percentage of gated cells with CD8α and CD8β markers based on isotype-matched control antibodies. Data are expressed as the percent of total gated population of lymphocytes. TPN administration led to a loss of the CD8αβ+IEL subset. IL-7 administration attenuated the loss of CD8αβ+IEL associated with TPN administration (TPN+IL-7). Using anti-IL-7 receptor antibody (IL-7R blockade), led to a significant decrease in the CD8αβ+ IEL subset when compared with controls.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the CD44+ IEL. CD44 was used as a marker of IEL maturation. TPN resulted in a significant decrease in the CD8+CD44+ IEL, P<0.05 compared to control mice. IL-7 administration in TPN treated mice attenuated the decrease in CD8+CD44+ and CD4+CD44+ IEL subsets when compared with the TPN group (P<0.05 compared to controls). Blocking IL-7R also resulted in a significant decrease in CD4+CD44+ and CD8+CD44+ sub-populations when compared with Controls (n =6 each group, *P<0.05).

Figure 5.

Distribution of IEL phenotypes. TPN administration led to a loss of CD4+CD8+IEL and CD4+CD8− subsets. IL-7 administration significantly attenuated the loss of CD4+CD8+, and CD4+CD8− IEL sub-populations associated with TPN administration. Blocking IL-7R with anti-IL-7R antibody resulted in a significant decrease in both CD4+CD8− and CD4+CD8+ IEL compared to controls. (n =6 each group, *P<0.05).

The change in the number of IEL after TPN administration was also studied. We found that TPN administration led to a significant decrease in IEL numbers when compared with controls (8.1±1.7 versus 5.2±0.8 for control and TPN groups, respectively (number of cells × 106; P<0.05).

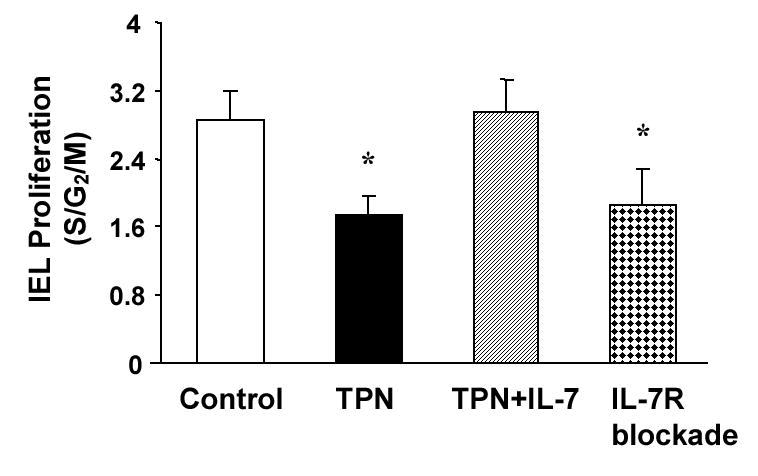

Changes in IEL proliferation

Because of the profound effect of TPN on IEL phenotypic changes and decline in the number of IEL, the non-stimulated percent of proliferating IEL (i.e., spontaneously proliferating lymphocytes) was determined. IEL proliferation declined to 1.74±0.23% with TPN administration compared to a mean of 2.86±0.33% in the control (enterally fed) group. Thus, 7 days of TPN administration led to a 1.6-fold decline in IEL proliferation (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

TPN results in a decline in the proportion of IEL that are in in active cell proliferation. IEL were surface-labeled with fluorochrome-conjugated antibody to CD3, and then treated with propidium iodide for detection of cell cycle status using flow cytometric analysis. Histograms were generated by gating on IEL populations and displaying the cell cycle. TPN administration significantly decreased IEL proliferation when compared with Controls, P<0.05. Administration of IL-7 to TPN mice attenuated this decline, and IL-7R antibody replicated the decline in IEL proliferation. Results are the percentage of IEL in a proliferative phase (as determined by cells in the S/G2/M cell cycle phases). Results are the mean of n=6 mice in each group, *P<0.05 compared to the control group.

IEL IL-7R expression

IL-7 receptor (IL-7R) expression has been detected on IEL and lamina propria lymphocytes (32, 35). To determine if local EC-derived IL-7 production affects the neighboring IEL through the IL-7/IL-7R dependent signaling pathway, the IL-7R expression of various IEL sub-populations was studied.

IL-7R expression on IEL sub-populations

IEL were sorted by flow cytometry according to the phenotypic cell markers: CD4, CD8αα, CD8αβ, αβ-TCR and γδ-TCR. As shown in Figure 7, IL-7R mRNA expression was identified on CD4+,CD8αα+, as well as the CD8αβ+ IEL subtypes; IL-7R was also identified in both αβ-TCR+ IEL and γδ-TCR+ IEL sub-populations.

Figure 7.

Composite gel demonstrating the expression of IL-7 receptor (IL-7R) mRNA in different IEL sub-populations. Samples are from representative specimens of various IEL sub-populations. Cells were purified using flow cytometry sorting. RT-PCR results demonstrated that CD4+, CD8αβ+, and CD8αα+ IEL sub-populations, as well as αβ-TCR+ and γδ TCR+ IEL subtypes express IL-7R mRNA. Results were consistently noted from at least three mice in each group.

Flow cytometry was also used to confirm surface protein expression of IL-7R in IEL sub-populations. Results are expressed as both the percent of IL-7R+ cells for all gated IEL cells, as well as the percent of IL-7R+ cells for each IEL sub-population. Similar to the mRNA analysis, IL-7R was observed in αβ-TCR+, γδ-TCR+, CD4+, as well as CD8+ IEL populations (Figure 8). CD4+ IEL had a higher number of IL-7R positive cells (2.2±0.22% of all gated IEL, or 42.3% of CD4+ IEL were IL-7R positive) compared to the CD8+ IEL subtype (13.6±2.4% of all gated IEL, or 16.2% of CD8+ IEL were IL-7R positive). Additionally, αβ-TCR+ IEL had a nearly 2-fold higher IL-7R expression compared to γδ-TCR+ IEL: 20.4±3.8% of all gated IEL, or 35.4% of αβ-TCR+ IEL (were IL-7R positive), compared to 7.7±4.7% of all gated IEL, or 20.9% of γδ,-TCR+ IEL were found to be IL-7R positive (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Flow cytometric analysis of IL-7 receptor (IL-7R) expression in isolated IEL. Results are expressed as the mean percent of IL-7R+ cells in all gated IEL (n=6), with a minimum of 10,000 IEL analyzed per mouse. Note that the percentage of IL7R+ cells was greatest in the CD4+ and αβ-TCR+ IEL sub-populations, relative to the total number of cells in each of these subtypes.

Changes in IEL IL-7R mRNA expression after TPN administration: Because IL-7 expression signals through IL-7R in the intestinal mucosa (41), we hypothesized that TPN-associated IEL changes may also affect IEL IL-7R expression. IEL IL-7R mRNA expression (normalized to beta actin expression) significantly decreased (0.48±0.2 in TPN vs. 0.84±0.02 in Control) after TPN administration compared with controls (P<0.05, based on n=6 per group).

Changes in IEL with IL-7R Blockade

To further confirm that a decline in EC-derived IL-7 accounts for the observed changes in the IEL with TPN administration, anti-IL-7R antibody was administered to enterally fed mice. Blockade of IL-7R resulted in several IEL phenotype changes that were similar to those observed with TPN administration. The CD8αβ+IEL sub-population was affected most profoundly, decreasing by 55% compared to controls (Figure 3). IL-7R blockade also caused significant declines in the CD4+CD8−, CD4+CD8+ (Figure 5), CD4+CD44+, as well as the CD8+CD44+ subsets compared to controls (Figure 4). Coincident with these phenotypic changes, IL-7R blockade also resulted in a significant decline in total IEL numbers when compared with the control group (P<0.05, 4.2±0.4 vs. 8.1±1.7 × 106 IEL cells for the IL-7R blockade and Control groups, respectively).

The effect of blocking IL-7R on IEL proliferation was also studied. Similar to mice which were given TPN, the basal proliferation rate decreased to 1.9% compared with 2.8% in the control group. Thus, IL-7R blockade led to a 32% decline in the IEL proliferation rate when compared with control mice (Figure 6).

IEL changes with IL-7 administration to TPN mice

We next investigated if exogenous administration of IL-7 could attenuate the observed IEL changes associated with TPN administration. Exogenous IL-7 was given to TPN treated mice starting on the first day of TPN administration and continued twice daily for 7 days. IL-7 administration significantly attenuated the loss of the CD8αβ+ IEL sub-population observed with TPN (Figure 3). The percent of CD8αβ+ IEL in the IL-7 treated TPN group was similar to the levels in the control (enterally fed) group, and was significantly higher than values in the TPN group (P<0.05). IL-7 administration in TPN mice also resulted in a significant increase in the percentage of CD44+ IEL (p<0.05). The CD8+CD44+ IEL population was more than 2-fold higher in IL-7 treated mice compared to TPN mice (Figure 4). IL-7 administration also attenuated the loss of CD4+CD44+ IEL after TPN administration (Figure 4). CD4+CD8+ sub-populations were also investigated: IL-7 administration significantly attenuated the loss of the CD4+CD8+, and CD4+CD8− IEL sub-populations during TPN administration. IL-7 administration to TPN mice significantly blunted the decline in IEL proliferation. IEL proliferation was 2.95±0.39% in the IL-7 treated group, and was not significantly different that the control group (2.44±0.29%; P>0.05; Figure 6). Finally, IL-7 administration was also effected in preventing the observed decline in the number of IEL after TPN (P< 0.05). With IL-7 administration, the number of small intestinal IEL rose to 12.9±3.4 ×106 per mouse, compared to 5.2±0.8 ×106 in the TPN group.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that TPN administration led to a significant decrease in EC-derived IL-7 expression, as well as to significant changes in the IEL phenotype, and to a decline in total IEL numbers. Exogenous IL-7 administration was able to attenuate most of these TPN-associated IEL changes. In addition, IL-7R blockade in enterally fed mice led to IEL phenotypic changes that were similar to those seen after TPN. This supports the concept that the decline in EC-derived IL-7 expression with TPN administration may be an important mechanism to account for many of the observed changes to the IEL. The marked changes to the intestinal immune system with administration of TPN is a significant clinical problem. TPN administration in a number of clinical studies has been associated with a increased rate of infections and septic episodes (20, 27). It is also thought that the source of sepsis may be due to an underlying loss in the function of the intestinal mucosal immune system (16, 31, 38). Thus, understanding potential mechanisms responsible for these changes in the IEL may allow for improved strategies to prevent TPN-associated infections.

The predominant IEL sub-population in mice is CD8+CD4− (70–85% of the total IEL number) (10). IEL also have a large number of γδ-TCR+ cells; and up to 50% of IEL are γδ-TCR+, compared to less than 2% of peripheral blood lymphocytes, in mice (16). Additionally, IEL are believed to originate from both a thymic-independent (29) and thymic-dependent source (10). Alterations in the luminal environment produce significant changes in the IEL (16). This study found that there is a significant decrease in the CD4+CD8−; CD4+CD8+; and CD4+CD44+, and CD8+CD44+ IEL sub-populations, as well as a loss of CD8αβ+ IEL after TPN administration in mice. The CD4+ IEL are known to be very responsive to exogenous stimulation, and their loss may explain the observed decrease in IEL proliferation with TPN (16). The reduction in CD44+ cells suggests a shift to a less mature IEL. The precise etiology of these IEL changes is uncertain.

It is well appreciated that IL-7 can promote growth and differentiation of many T cell phenotypes (2), and this is supported by the wide range of IEL sub-populations which express IL-7R. IL-7 is also essential for early developmental processes such as the differentiation of pre-T cells into mature thymocytes (50). This latter function cannot be performed by any other known cytokine (50). In the absence of IL-7, homeostatic proliferation of naive T-cells is almost completely abolished, and the lifespan of naive T-cells is greatly reduced (34). In vivo, administration of IL-7 has been demonstrated to enhance peripheral T-cell functional capacity and expand the peripheral T-cell population (19). Geiselhart, et al (9) has reported that IL-7 administration alters the peripheral T-cell CD4:CD8 ratio, and results in an increase in peripheral T cell numbers and altered function. Watanabe, et al observed that exogenous IL-7 administered to mice resulted in a stimulation of lamina propria lymphocytes (35). Interestingly, in an IL-7 over-expression transgenic mouse model, IL-7R expression on IEL was found to be increased (36). Recently, we reported that IL-7 administration to healthy wild-type mice, led to a significant increase in CD8αβ+ IEL, and to a significant, relative decline in the percentage of the CD8αα+ IEL sub-population (46). IL-7 administration also significantly increased the percentage of CD8+,CD44+ IEL, and led to a significant change in the IEL cytokine expression function (46). These data suggest that IL-7 may be essential for the on-going maintenance of the IEL in mature mice. The mechanisms by which the IEL phenotype changes with TPN are not known. TPN results in a loss of villus height, decline in epithelial barrier function, loss of EC proliferation and a rise in EC apoptosis (42, 43). The increased EC apoptosis and decrease in EC proliferation with TPN administration may contribute to the loss of EC-derived IL-7 expression. The decline of EC-derived IL-7 expression may also be due to a loss of foreign antigen stimulation (from enteral food products) which enterocytes typically encounter several times a day.

Recent studies have demonstrated that interactions between mucosal lymphocytes and intestinal EC are crucial in regulating the immune response in the intestinal mucosa (33, 35, 42, 43). EC have been shown to act as antigen presenting cells for both CD4+ and CD8+ IEL (14, 25). EC are known to produce a number of immunologically important cytokines, including IL-6 (13); IL-7, IL-8, and IL-10 (8, 35). Of these cytokines, the IL-7/IL-7R dependent signaling pathway has been shown to play a crucial role in regulating the immune response in the intestinal mucosa (22, 33, 35, 36, 41). IL-7 knock out and IL-7R knock out mice show distinct declines in absolute numbers of thymocytes and IEL (24). Kanai et al (15) found that anti-IL-7 antibody treatment disturbed the induction of αβ-TCR+ T-cells after athymic nude mice were implanted with fetal thymocytes.

IL-7 receptors have been detected on the surface of thymocytes, peripheral T cells, and human IEL and LP lymphocytes, as well as cells of B lineage (32, 35). A study from Okazawa et al (30) recently reported that colonic αβ-TCR+ and γδ-TCR+ IEL express IL-7R. In their study, IL-7 receptor expression was identified in αβ-TCR+ IEL and γδ-TCR+ IEL phenotypes, as well as CD4+ and CD8αβ+, CD8αα+ IEL in small bowel using both flow cytometry and RT-PCR. This IL-7R distribution was similar to that found in our current study.

In this study we found that blockade of the IL-7 receptor resulted in several phenotypic IEL changes that were quite similar to those observed in TPN mice. These changes include a loss of the CD8αβ+, CD4+ CD44+, and CD4+ (including the CD4+ CD8+ and CD4+ CD8−) IEL sub-populations. The fact that blocking IL-7R only partially replicated some of the changes observed in the IEL phenotype after TPN may indicate that other mechanisms are also involved in this process. Additionally, IEL numbers were lower in the IL-7 blockade group compared to the TPN group. This is most likely due to the fact that, although IL-7 expression is reduced with TPN administration, local levels of IL-7 were still present in the TPN group; whereas IL-7R blockade resulted in a much greater decline in this IL-7/IL-7R pathway. The incomplete replication of the phenotype with receptor blockade may also be due to the fact that the turnover of the IEL population is slower than most lymphocyte populations (28). Nevertheless, exogenous IL-7 administration prevented the development of the majority of TPN-associated IEL phenotype changes and the decline in total IEL numbers, underscoring the importance of this cytokine in the development of TPN-induced changes to the mucosal immune system. A previous study of ours has shown that there is a close physical close communication between EC-derived IL-7 and the neighboring IEL by the co-localization of these cell populations (46). This data suggest that cell-to-cell interactions between EC and IEL, via IL-7, could be an important model of communication for the maintenance and activation of the IEL. The fact that the highest expression of IL-7R was found on CD4+ and αβ-TCR+ IEL may be quite important as there are significant functional differences between IEL sub-populations. Namely, the CD4+ and αβ -TCR+ IEL populations are known to have a much greater proliferative capacity compared to CD8+ and γδ-TCR IEL sub-populations (5, 18). These major differences in IEL proliferation observed by these investigators may well be explained by our finding of the highest expression of IL-7R on CD4+ and αβ -TCR+ IEL. The changes in IEL phenotype may play an important role in the EC function. We have previously shown that γδ-TCR+IEL derived KGF has an important role in the EC proliferation (42). We also found that IEL- derived IFN-γ plays an important role in the increase of EC apoptosis (43). All these finding suggested that there is a strong cross-talk between EC and IEL. Future studies will need to focus on the how the reported changes in IEL after IL-7 administration affects intestinal EC function.

Our study closely corroborated some of the findings of a recent publication by Fukatsu, et al (6). In their work, the authors noted that exogenous administration of IL-7 increased the number of T-cells in Peyer’s patches and IEL in a TPN rodent model. The authors noted that despite this increase in T-cells, they did not find an improvement in the TPN-associated decline in IgA levels. The examination of IEL in their study was, however, quite limited. These authors did not examine the role of endogenous IL-7 in the modulation of the specific IEL phenotype, nor did they examine how IL-7 might affect IEL proliferation, as done in our current study. Further, an assessment of the loss of IL-7 (as performed in our study) was also not investigated by these authors.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that TPN administration causes significant changes to both intestinal EC and IEL populations. This study further confirms a close communication between EC-derived IL-7 and IEL. The decline in production of EC-derived IL-7 after TPN administration may present an important mechanism for resultant TPN-associated IEL changes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant 5R01AI044076-08 (to DHT) and an ASPEN Rhoads Research Foundation Maurice Shils Grant (to HY), as well as the NIH through the University of Michigan’s Cancer Center Support Grant (5 P30 CA46592).

Footnotes

Presented in part at the Annual Congress of the American Gastroenterology Association, May 18-23, 2004, New Orleans, LA, U.S.A.

Grant support: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant 5R01AI044076-08 (to DHT) and an ASPEN Rhoads Research Foundation Maurice Shils Grant (to HY), as well as the National Institutes of Health through the University of Michigan’s Cancer Center Support Grant (5 P30 CA46592).

References

- 1.Anderson G, Steinberg E. DRG’s and specialized nutritional support: the need for reform. J Paren Enter Nutr. 1986;10:3–10. doi: 10.1177/014860718601000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatia SK, Tygrett LT, Grabstein KH, Waldschmidt TJ. The effect of in vivo IL-7 deprivation on T cell maturation. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1399–1409. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faltynek CR, Wang S, Miller D, Young E, Tiberio L, Kross K, Kelley M, Kloszewski E. Administration of human recombinant IL-7 to normal and irradiated mice increases the numbers of lymphocytes and some immature cells of the myeloid lineage. J Immunol. 1992;149:1276–1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujihashi K, Kawabata S, Hiroi T, Yamamoto M, McGhee JR, Nishikawa S, Kiyono H. Interleukin 2 (IL-2) and interleukin 7 (IL-7) reciprocally induce IL-7 and IL-2 receptors on gamma delta T-cell receptor-positive intraepithelial lymphocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:3613–3618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujihashi K, Yamamoto M, McGhee JR, Beagley KW, Kiyono H. Function of alpha beta TCR+ intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes: Th1- and Th2-type cytokine production by CD4+CD8− and CD4+CD8+ T cells for helper activity. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1473–1481. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.11.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukatsu K, Moriya T, Maeshima Y, Omata J, Yaguchi Y, Ikezawa F, Mochizuki H, Hiraide H. Exogenous interleukin 7 affects gut-associated lymphoid tissue in mice receiving total parenteral nutrition. Shock. 2005;24:541–546. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000183237.32256.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukui T, Katamura K, Abe N, Kiyomasu T, Iio J, Ueno H, Mayumi M, Furusho K. IL-7 induces proliferation, variable cytokine-producing ability and IL-2 responsiveness in naive CD4+ T-cells from human cord blood. Immunol Lett. 1997;59:21–28. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(97)00093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galliaerde V, Desvignes C, Peyron E, Kaiserlian D. Oral tolerance to haptens: intestinal epithelial cells from 2,4- dinitrochlorobenzene-fed mice inhibit hapten-specific T cell activation in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1385–1390. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geiselhart LA, Humphries CA, Gregorio TA, Mou S, Subleski J, Komschlies KL. IL-7 administration alters the CD4:CD8 ratio, increases T cell numbers, and increases T cell function in the absence of activation. Journal of Immunology. 2001;166:3019–3027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guy-Grand D, Vassalli P. Gut intraepithelial T lymphocytes. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90012-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayday A, Theodoridis E, Ramsburg E, Shires J. Intraepithelial lymphocytes: exploring the Third Way in immunology. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:997–1003. doi: 10.1038/ni1101-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He YW, Malek TR. The structure and function of gamma c-dependent cytokines and receptors: regulation of T lymphocyte development and homeostasis. Crit Rev Immunol. 1998;18:503–524. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v18.i6.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung HC, Eckmann L, Yang SK, Panja A, Fierer J, Morzycka-Wroblewska E, Kagnoff MF. A distinct array of proinflammatory cytokines is expressed in human colon epithelial cells in response to bacterial invasion. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:55–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI117676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiserlian D, Vidal K, Revillard JP. Murine enterocytes can present soluble antigen to specific class II-restricted CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:1513–1516. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenai H, Matsuzaki G, Nakamura T, Yoshikai Y, Nomoto K. Thymus-derived cytokine(s) including interleukin-7 induce increase of T cell receptor αβ+ CD4−CD8− T cells which are extrathymically differentiated in athymic nude mice. European Journal of Immunology. 1993;23:1818–1825. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiristioglu I, Antony P, Fan Y, Forbush B, Mosley RL, Yang H, Teitelbaum DH. Total parenteral nutrition-associated changes in mouse intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2002;47:1147–1157. doi: 10.1023/a:1015066813675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiristioglu I, Teitelbaum DH. Alteration of the intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes during total parenteral nutrition. Journal of Surgical Research. 1998;79:91–96. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiyono H, Fujihashi K, Taguchi T, Aicher WK, McGhee JR. Regulatory functions for murine intraepithelial lymphocytes in mucosal responses. Immunol Res. 1991;10:324–330. doi: 10.1007/BF02919716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komschlies KL, Gregorio TA, Gruys ME, Back TC, Faltynek CR, Wiltrout RH. Administration of recombinant human IL-7 to mice alters the composition of B-lineage cells and T cell subsets, enhances T cell function, and induces regression of established metastases. Journal of Immunology. 1994;152:5776–5784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kudsk K, Croce M, Favian T, Minard G, Tolley E, Poret H, Kuhl M, Brown R. Enteral versus parenteral feeding. Effects on septic morbidity after blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma. Ann Surg. 1992;215:503–511. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199205000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunisawa J, Takahashi I, Okudaira A, Hiroi T, Katayama K, Ariyama T, Tsutsumi Y, Nakagawa S, Kiyono H, Mayumi T. Lack of antigen-specific immune responses in anti-IL-7 receptor alpha chain antibody-treated Peyer’s patch-null mice following intestinal immunization with microencapsulated antigen. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2347–2355. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200208)32:8<2347::AID-IMMU2347>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laky K, Lefrancois L, Lingenheld EG, Puddington L. Enterocyte expression of interleukin 7 induces development of gamma delta T cells and Peyer’s patches. Journal of Experiment Medicine. 2000;191:1569–1580. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Kudsk KA, Gocinski B, Dent D, Glezer J, Langkamp-Henken B. Effects of parenteral and enteral nutrition on gut-associated lymphoid tissue. The Journal of Trauma. 1995;39:44–52. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199507000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maki K, Sunaga S, Komagata Y, Kodaira Y, Mabuchi A, Karasuyama H, Yokomuro K, Miyazaki JI, Ikuta K. Interleukin 7 receptor-deficient mice lack gammadelta T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7172–7177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayer L, Shlien R. Evidence for function of Ia molecules on gut epithelial cells in man. J Exp Med. 1987;166:1471–1483. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.5.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mertsching E, Wurster AL, Katayama C, Esko J, Ramsdell F, Marth JD, Hedrick SM. A mouse strain defective for alphabeta versus gammadelta T cell lineage commitment. Int Immunol. 2002;14:1039–1053. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore F, Moore E, Jones T. TEN vs. TPN following major abdominal trauma: reduced septic morbidity. J Trauma. 1989;29:916–923. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198907000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosley RL, Klein JR. Repopulation kinetics of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes in murine bone marrow radiation chimeras. Transplantation. 1992;53:868–874. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199204000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosley RL, Styre D, Klein JR. Differentiation and functional maturation of bone marrow-derived intestinal epithelial T cells expressing membrane T cell receptor in athymic radiation chimeras. J Immunol. 1990;145:1369–1375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okazawa A, Kanai T, Nakamaru K, Sato T, Inoue N, Ogata H, Iwao Y, Ikeda M, Kawamura T, Makita S, Uraushihara K, Okamoto R, Yamazaki M, Kurimoto M, Ishii H, Watanabe M, Hibi T. Human intestinal epithelial cell-derived interleukin (IL)-18, along with IL-2, IL-7 and IL-15, is a potent synergistic factor for the proliferation of intraepithelial lymphocytes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:269–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Renegar KB, Kudsk KA, Dewitt RC, Wu Y, King BK. Impairment of mucosal immunity by parenteral nutrition: depressed nasotracheal influenza-specific secretory IgA levels and transport in parenterally fed mice. Ann Surg. 2001;233:134–138. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200101000-00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sudo T, Nishikawa S, Ohno N, Akiyama N, Tamakoshi M, Yoshida H. Expression and function of the interleukin 7 receptor in murine lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:9125–9129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki K, Oida T, Hamada H, Hitotsumatsu O, Watanabe M, Hibi T, Yamamoto H, Kubota E, Kaminogawa S, Ishikawa H. Gut cryptopatches: direct evidence of extrathymic anatomical sites for intestinal T lymphopoiesis. Immunity. 2000;13:691–702. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan JT, Dudl E, LeRoy E, Murray R, Sprent J, Weinberg KI, Surh CD. IL-7 is critical for homeostatic proliferation and survival of naive T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8732–8737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161126098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe M, Ueno Y, Yajima T, Iwao Y, Tsuchiya M, Ishikawa H, Aiso S, Hibi T, Ishii H. Interleukin 7 is produced by human intestinal epithelail cells and regulates the proliferation of intestinal mucosal lymphocytes. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;95:2945–2953. doi: 10.1172/JCI118002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe M, Ueno Y, Yajima T, Okamoto S, Hayashi T, Yamazaki M, Iwao Y, Ishii H, Habu S, Uehira M, Nishimoto H, Ishikawa H, Hata J, Hibi T. Interleukin 7 transgenic mice develop chronic colitis with decreased interleukin 7 protein accumulation in the colonic mucosa. J Exp Med. 1998;187:389–402. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe M, Yamazaki M, Okamoto R, Ohoka S, Araki A, Nakamura T, Kanai T. Therapeutic approaches to chronic intestinal inflammation by specific targeting of mucosal IL-7/IL-7R signal pathway. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2003;2:119–123. doi: 10.2174/1568010033484269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wildhaber BE, Yang H, Spencer AU, Drongowski RA, Teitelbaum DH. Lack of enteral nutrition--effects on the intestinal immune system. J Surg Res. 2005;123:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Witkowski J, Miller R. Increased function of P-glycoprotein in T lymphocyte subsets of aging mice. Journal of Immunology. 1993;150:1296–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yada S, Nukina H, Kishihara K, Takamura N, Yoshida H, Inagaki-Ohara K, Nomoto K, Lin T. IL-7 prevents both caspase-dependent and -independent pathways that lead to the spontaneous apoptosis of i-EIL. Cellular Immunology. 2001;208:88–95. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamazaki M, Yajima T, Tanabe M, Fukui K, Okada E, Okamoto R, Oshima S, Nakamura T, Kanai T, Uehira M, Takeuchi T, Ishikawa H, Hibi T, Watanabe M. Mucosal T cells expressing high levels of IL-7 receptor are potential targets for treatment of chronic colitis. J Immunol. 2003;171:1556–1563. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang H, Antony PA, Wildhaber BE, Teitelbaum DH. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocyte gammadelta-T cell-derived keratinocyte growth factor modulates epithelial growth in the mouse. J Immunol. 2004;172:4151–4158. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang H, Fan Y, Teitelbaum DH. Intraepithelial lymphocyte-derived interferon-gamma evokes enterocyte apoptosis with parenteral nutrition in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G629–637. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00290.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang H, Finaly R, Teitelbaum DH. Alteration in epithelial permeability and ion transport in a mouse model of total parenteral nutrition. Critical Care Medicine. 2003;31:1118–1125. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000053523.73064.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang H, Kiristioglu I, Fan Y, Forbush B, Bishop DK, Antony PA, Zhou H, Teitelbaum DH. Interferon-gamma expression by intraepithelial lymphocytes results in a loss of epithelial barrier function in a mouse model of total parenteral nutrition. Ann Surg. 2002;236:226–234. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200208000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang H, Spencer AU, Teitelbaum DH. Interleukin-7 administration alters intestinal intraepithelial lymphocyte phenotype and function in vivo. Cytokine. 2005;31:419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang H, Teitelbaum DH. Novel agents in the treatment of intestinal failure: humoral factors. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:S117–121. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang H, Wildhaber B, Tazuke Y, Teitelbaum DH. Harry M. Vars Research Award. Keratinocyte growth factor stimulates the recovery of epithelial structure and function in a mouse model of total parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002;26:333–340. doi: 10.1177/0148607102026006333. discussion 340–331, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zarzaur BL, Ikeda S, Johnson CD, Le T, Sacks G, Kudsk KA. Mucosal immunity preservation with bombesin or glutamine is not dependent on mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 expression. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002;26:265–270. doi: 10.1177/0148607102026005265. discussion 270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zlotnik A, Moore TA. Cytokine production and requirements during T-cell development. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:206–213. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]