INTRODUCTION

Patient access to health information and personal health records is becoming increasingly important in today's healthcare society. With eight out of ten online users searching for medical information, patients seek to be informed in matters of health [1]. In parallel with this high demand, the Institute of Medicine's Crossing the Quality Chasm report further highlights the critical need for patient involvement in the healthcare process. One of six proposed aims for improving quality of care, the “patient-centered” approach of providing care that respects and incorporates patient preferences in clinical decision making, requires adequate information, communication and education [2, 3].

The National Library of Medicine spearheads several consumer health initiatives, such as MedlinePlus, NIH Senior Health, and ClinicalTrials.gov, designed to get medical information directly into the hands of patients [4–6]. These services present one mechanism for increasing patient access to information, but do not address directly the communication between patient and provider. Information technology systems such as electronic health records and patient-focused web portals offer another mechanism for facilitating increased patient-provider communication and information sharing. Their proliferation also presents information professionals opportunities to further extend support for evidence-based medicine, consumer health and health literacy efforts directly to patients via processes that are driven by patient-specific data [7–9]. This paper reports on the Eskind Biomedical Library's (EBL) collaboration with informatics and clinical teams to foster informed patient decision-making and participatory healthcare through an online patient portal.

BACKGROUND

The Eskind Biomedical Library has a solid history of targeted, innovative provision of information services to the Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) community. The library's firm integration with the clinical and research arenas is evidenced by the success of the Informatics Consult Services; these services have brought librarianship expertise directly to the bedside and research bench since 1996 [10–12]. In 1997, with funding received from the Medical Center, the EBL introduced an Informatics Consult Service specifically designed to provide patients with health information from carefully selected resources appropriate to their education and health literacy levels. The Patient Informatics Consult Service (PICS) was designed to allow patients and patient family members to request personalized health information based on their diseases and conditions by having a Prescription for Information form completed by their physician [13].

This approach requires that patients physically enter the library, adding an extra step for individuals who may already be experiencing a great deal of stress over a medical issue. The PICS service was, in addition, never set up to reach a large number of patients and is designed to inform the patient and the treating physician on specific medical questions that need further research and in some instances further explanation. To complement this approach EBL more recently collaborated with a physician champion in an outpatient clinic to determine optimal strategies to deliver best-evidence health information to patients on a larger scale [14]. Concurrently, clinicians and software developers of the Informatics Center were engaged in the creation and refinement of a secure, interactive website specifically designed for patients which would integrate with the institution's electronic medical record system. As a unit of the Informatics Center (IC), EBL has ample opportunity to collaborate and partner with informatics colleagues in research and development initiatives that call for library expertise. When the IC initiated the clinical patient portal project, the library saw an opportunity for partnering and correcting some of the shortcomings of the previous patient information approaches, i.e., scalability and ease of access for patients in need of information.

THE LIBRARY'S ROLE

The MyHealthatVanderbilt (MHAV) portal encourages patients to become proactive partners in their care management and facilitates open communication with healthcare providers. Interactive features such as appointment scheduling, online bill payment, and secure electronic messaging to providers engage patients in various steps of the healthcare process [15–17]. Patient data is seamlessly extracted from StarPanel, the Medical Center's electronic health record system [18–20], and disclosed to the patient within the MHAV portal. From the beginning of the portal's extensive re-development process in 2005 (which added numerous enhancements), the library has played a key role in the provision of health information and evidence to foster increased patient health literacy. This effort uses several mechanisms: health topics; inclusion of journalist-written news stories; and patient-oriented information about lab tests.

Health topics

Health topics included in MHAV may be disease-specific, such as diabetes or Crohn's disease, or may be preventive health topics, such as colon cancer screening. To create customized links to information, the library works closely with healthcare teams in the outpatient clinics to select the most relevant topics given the clinic's specific patient population. After identifying the most relevant health topics for an outpatient clinic, trained EBL Health Information Analysts (HIAs) and junior librarians select the best online consumer sources. At EBL, the HIA job category was created in 1996 for non-librarians who completed a comprehensive individualized learning plan and verification of skills [21–22]. For the MHAV project, HIAs were handpicked based on their aptitude and overall interest in consumer health. Selection of consumer sources is based upon criteria such as currency, authority and accuracy; these criteria are modeled after MedlinePlus Quality Guidelines and the Medical Library Association's User's Guide to Finding and Evaluating Health Information Online [23–24]. The resources are organized into subcategories intended to be easily recognizable by patients.

As part of the library's mentoring process, a designated experienced EBL librarian then reviews the collection of links gathered by the HIAs and junior librarians and provides feedback and suggestions for improvement. The EBL team sends the vetted list of health topic websites back to the clinical team to solicit input on relevance and resource selection. After reaching consensus on the website selections for a given topic, and after securing permission from hosting sites to link to their online materials, EBL team members enter the topics into an internally created MySQL database. The MHAV portal software extracts data from this database to present the selected sites for each topic into the portal. Creating a new health topic typically takes one month to complete. Ongoing maintenance for the EBL team includes regularly monitoring links for currency and appropriateness. Figure 1 shows an example health topic page in MyHealthatVanderbilt.

Figure 1.

A library-provided health topic in MyHealthatVanderbilt

Upon logging into the MHAV portal, patients are automatically presented with disease topics relevant to them, based on specific information from within their medical record. This information is derived from two primary sources within the record. The first source is the list of International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic codes for each patient. The coded list facilitates easy mapping, but its utility is somewhat diminished by the fact that the codes result from the billing process, rather than being entered directly by clinicians. The second source is the free-text Problems section of the patient summary, which (unlike the ICD-9-CM codes) is actively and collectively maintained by VUMC care providers. Codes derived from the patient's problem list, combined with the ICD-9-CM codes from billing are automatically matched via computer algorithms to the ICD-9-CM codes assigned by library staff to each disease topic. When a match is made, the appropriate disease topic is displayed in the portal, allowing patients to see links to information directly relevant to their care. Preventive health topics are delivered to a specific patient based on demographic characteristics and matched according to U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations [25]. They are also complemented by additional topics of significant public importance. For example, a 65-year old woman who logs into to MHAV will receive information on screening for breast cancer, osteoporosis and colorectal cancer.

Journalist news stories

To accompany the library-provided content, the Medical Center employs a freelance journalist to write original articles about timely health information of seasonal importance, such as the flu or spring allergies, or recent newsworthy developments from the primary literature, such as aspirin's role as a safe and effective agent for the prevention of heart attack or stroke. Recognizing the library's expertise in information provision, the MHAV team—comprised of physicians, patient account representatives, medical center web team, marketing team, informatics center developers, and library members—solicited the library's collaboration with the journalist to supplement the news stories published within the portal with links to librarian-selected authoritative websites. Each news story contains, where appropriate, links to targeted information providing more detail on the subject.

Links to lab information

The MHAV portal allows patients to view the results of selected lab tests and other diagnostic studies, exported directly from the patient's electronic medical record. Following extensive intra- and inter-institutional consultations, VUMC formulated a policy that allows patients to access electronically the results of medical tests conducted at the Medical Center. The policy is aimed at facilitating disclosure of test results to the patient, while encouraging health care providers to communicate those results—and their interpretation—to the patient in a timely manner. Results from most laboratory tests, radiological studies, and an increasing number of other diagnostic tests are now presented automatically to the patient after a delay that ranges from seven to fourteen days. However, in cases where the interpretation of the results may be difficult for a layperson, or which might cause unnecessary patient concern or anxiety, the results are not disclosed via the portal by policy. In those cases, an explicit action by the care provider is required to initiate electronic disclosure.

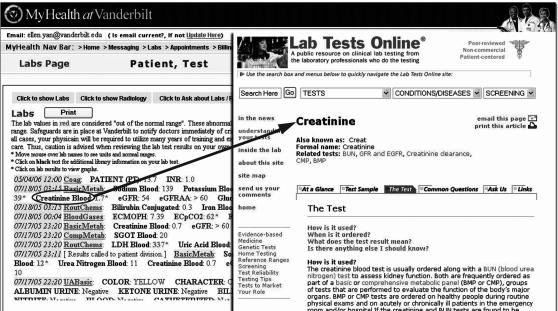

To provide patients with a greater understanding of their results, the library mapped over 300 of the most commonly requested lab tests in the Medical Center to Lab Tests Online, a consumer-oriented, peer-reviewed website developed by the American Association for Clinical Chemistry [26]. The link to Lab Tests Online is displayed by selecting the name of the lab test on the lab results display view; Figure 2 shows an example link.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of test patient lab display in MyHealthatVanderbilt

Given that the display of lab results was not originally designed for the consumer, the library-provided links to Lab Tests Online are a particularly important feature, as they present lab test details through consumer-oriented explanations.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

As of July 2006, there were approximately twenty-five health topics linked to MHAV, with 15% of patients (2,700/18,000) using the portal having accessed the library-provided links. Since July 2005, an average of 850 new user accounts have been created each month. Anecdotal feedback on the integrated lab links—collected from reports of clinical team members, patient responses during MHAV focus groups, and comments from other MHAV team members—has thus far been highly positive; both patients and clinicians have expressed enthusiastic appreciation for the health information materials. The library plans to move forward with support for the portal by adding new health topics, and conducting further refinement and assessment of the content via patient focus groups and other feedback mechanisms to increase usage. The EBL aims to provide access to the highest caliber of health information in a manner that thoroughly considers patient information-seeking characteristics and engagement. With the growing emergence of online patient portals, medical librarians can leverage opportunities that exist within electronic health record systems to educate patients and provide them with relevant, evidence-based information. This strategy is key in further scaling up library services.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jim Jirjis for his assistance in MHAV policy and development processes, Shannon Potter for her oversight of the health topics, and Annette Williams for her assistance with the manuscript preparation.

The authors also thank Dr. Gary Byrd for serving as guest editor and coordinating the editing, peer review and publication decision process, as two of the authors are current members for the Journal of the Medical Library Association Editorial Board.

Footnotes

* Preliminary version of this paper presented at MLA '06, the 106th annual meeting of the Medical Library Association, Phoenix, AZ, May 23, 2006.

REFERENCES

- Fox S. Health Information Online. [Web Document]. Pew Internet Fund. 2005 May 17. [cited 26 Jul 2006]. <http://www.pewinternet.org/PPF/r/156/report_display.asp>. [Google Scholar]

- Crossing the Quality Chasm:. A New Health System for the 21st Century. [Web Document]. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001. [cited 26 Jul 2005]. <http://www.nap.edu/books/0309072808/html/>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K, Schoenbaum SC, Audet AM.. A 2020 vision of patient-centered primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(10):953–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller N, Lacroix EM, Backus JE.. MEDLINEplus: building and maintaining the National Library of Medicine's consumer health Web service. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000;88(1):11–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. NIHSeniorHealth. [Web document]. Bethesda, MD: The Institutes, 2006. [rev. 7 July 2006; cited 25 July 2006]. <http://nihseniorhealth.gov/>. [Google Scholar]

- McCray AT, Dorfman E, Ripple A, Ide NC, Jha M, and Katz DG. et al. Usability issues in developing a Web-based consumer health site. Proc AMIA Symp 2000:556–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stead WW. Rethinking electronic health records to better achieve quality & safety goals. Annual Review of Medicine. In Press 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabretta N.. Consumer-driven, patient-centered health care in the age of electronic information. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002;90(1):32–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Fedyshin MS.. Consumer health informatics–integrating patients, providers, and professionals online. Med Ref Serv Q. 2002;21(3):35–50. doi: 10.1300/J115v21n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuse NB, Kafantaris SR, Miller MD, Wilder KS, Martin SL, Sathe NA, Campbell JD.. Clinical medical librarianship: the Vanderbilt experience. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1998;86(3):412–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florance V, Giuse NB, Ketchell DS.. Information in context: integrating information specialists into practice settings. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002;90(1):49–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon J.. Beyond the literature: bioinformatics training for medical librarians. Med Ref Serv Q. 2003;22(1):67–74. doi: 10.1300/J115v22n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MD, Gish KW, Giuse NB, Sathe NA, Carrell DL.. The Patient Informatics Consult Service (PICS): an approach for a patient-centered service. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2001;89(2):185–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuse NB, Koonce TY, Jerome RN, Cahall M, Sathe NA, Williams A.. Evolution of a mature clinical informationist model. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12(3):249–55. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govern P. ‘My Health’ site's traffic, capabilities growing fast. [Web Document]. VUMC Reporter. 2006 May 26. [cited 26 Jul 2006]. <http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/reporter/index.html?ID=4772>. [Google Scholar]

- Govern P. Some lab results now available online. [Web Document]. VUMC Reporter. 2005 December 2. [cited 26 Jul 2006]. <http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/reporter/index.html?ID=4394>. [Google Scholar]

- Govern P. New Web tool unites patients, clinical teams. [Web Document].VUMC Reporter 2005 January 7. [cited 26 Jul 2006]. <http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/reporter/index.html?ID=3691>. [Google Scholar]

- Giuse DA. Supporting communication in an integrated patient record system. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2003:1065. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirjis J, Patel NR, Aronsky D, Lorenzi N, Giuse DA.. Seeing stars: the creation of a core clinical support informatics product. Int J Healthcare Technology and Management. 2003;5(3/5/5):284–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hoot N, Weiss J, Giuse DA, Jirjis J, Peterson J, and Lorenzi N. Integrating communication tools into an electronic health record. Medinfo 2004;164. [Google Scholar]

- Giuse NB, Kafantaris SR, Huber JT, Lynch F, Epelbaum M, Pfeiffer J.. Developing a culture of lifelong learning in a library environment. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1999;87(1):26–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuse NB, Huber JT, Kafantaris SR, Giuse DA, Miller MD, Giles DE Jr, Miller RA, Stead WW.. Preparing librarians to meet the challenges of today's health care environment. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4(1):57–67. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1997.0040057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health/United States National Library of Medicine. MedlinePlus Quality Guidelines. [Web document]. Bethesda, MD: The Institutes, 2006 [rev. 14 Mar 2006; cited 25 July 2006]. <http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/criteria.html>. [Google Scholar]

- A user's guide to finding and evaluating health information on the Web. MLANET. [Web document]. Chicago, IL: Medical Library Association, 2006. [rev. 24 Oct 2005; cited 25 July 2006]. <http://www.mlanet.org/resources/userguide.html>. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations. [Web Document]. Agency for HealthCare Research and Quality. [cited 26 Jul 2006]. <http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstfix.htm#Recommendations>. [Google Scholar]

- American Association for Clinical Chemistry. Lab Tests Online. [Web document]. Washington, DC: The Association, 2006. [cited 25 July 2006]. <http://www.labtestsonline.org/index.html>. [Google Scholar]