Abstract

Objectives: The eighteen-month evaluation of a clinical librarian project (October 2003–March 2005) conducted in North Wales, United Kingdom (UK) assessed the benefits of clinical librarian support to clinical teams, the impact of mediated searching services, and the effectiveness of information skills training, including journal club support.

Methods: The evaluation assessed changes in teams' information-seeking behavior and their willingness to delegate searching to a clinical librarian. Baseline (n = 69 responses, 73% response rate) and final questionnaire (n = 57, 77% response rate) surveys were complemented by telephone and face-to-face interviews (n = 33) among 3 sites served. Those attending information skills training sessions (n = 130) completed evaluations at the session and were surveyed 1 month after training (n = 24 questionnaire responses, n = 12 interviews).

Results: Health professionals in clinical teams reported that they were more willing to undertake their own searching, but also more willing to delegate some literature searching, than at the start of the project. The extent of change depended on the team and the type of information required. Information skills training was particularly effective when organized around journal clubs.

Conclusions: Collaboration with a clinical librarian increased clinician willingness to seek information. Clinical librarian services should leverage structured training opportunities such as journal clubs.

Highlights

With a clinical librarian working in their team, clinicians reported that they were more willing to spend time searching for information related to patient care.

Clinicians in the current project were willing to delegate a range of queries, particularly urgent and important queries, to a clinical librarian.

Reactions to a clinical librarian service varied considerably among different teams.

Implications

Clinical librarian services need to be flexible and carefully targeted to maximize their educational and clinical care benefits.

The success of a clinical librarian service with a particular team is hard to predict in advance.

Services should be balanced between supporting health staff via mediated searching and empowering them to do their own searching effectively.

Structured skills support in journal clubs is valued by clinical staff.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical medical librarian programs as special projects may require evidence of their effectiveness, and this type of data has been difficult to obtain. One systematic review [1] of evaluations of clinical librarian services noted the lack of rigorous comparative research methods, and another systematic review [2] noted the lack of data on cost-effectiveness. The main impact of clinical librarian services appeared to be the perceived usefulness and quality of the information resources provided by the clinical librarians, with some studies suggesting that their impact on patient care is positive. A later study of the impact on patient care of clinical librarian services again echoed the need for higher quality evaluation designs, noting that some studies suggested that time savings (in terms of health professional time) and improved patient outcomes should be possible to demonstrate [3].

In the UK, the scope of clinical librarian activities varies considerably [4–5]. Government policy advocates evidence-based practice, and national policy for clinical governance describes the framework used to ensure that UK health-care organizations can demonstrate that their services are continuously striving for high quality care. As interpretations of the clinical governance requirements vary among hospitals and departments within each hospital, it is not surprising that clinical librarians find getting recognition difficult despite the likely positive contribution that clinical librarians could make to clinical governance [6].

The current paper describes the development and initial evaluation of the North Wales Clinical Librarian service, including assessment of changes in clinical team information behavior and information searching skills.

BACKGROUND

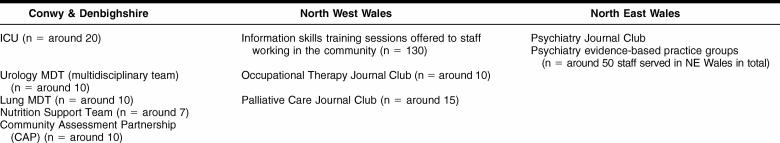

The clinical librarian project encompassed activities across 3 National Health Service (NHS) Hospital Trusts (about 60 miles, or 100 km, apart at the farthest points) in North Wales, UK (Table 1). NHS Trusts are non-profit, public sector health organizations.

Table 1 Location and size of teams

Clinical librarian services varied somewhat among the 3 Trusts and included information skills outreach training (North West Wales), working with 5 clinical teams (Conwy and Denbighshire) and working with 1 large multidisciplinary team (North East Wales) The clinical librarian serving these three locations (JR) worked closely with the evaluation team from the University of Wales Aberystwyth (JD, JT, CU). The evaluation objectives were to:

assess which aspects of the clinical librarian services were used

estimate the effect of information skills training on staff searching patterns and time taken to search

examine the benefits to clinical practice in terms of clinical governance activities and policies

examine whether information skills training affected staff skills and confidence

explore factors affecting librarian collaboration with multidisciplinary teams and attitudes towards the clinical librarian

The nature of clinical librarian support was determined in collaboration with each of the clinical teams and evolved throughout the project. Initially, the clinical librarian attended team meetings and dealt with requests for literature searches. In some teams, the focus of support activities changed to the journal club for the team. The journal club was restructured, with more intensive skills training sessions to prepare the junior doctors for their presentations at particular meetings. The information skills training sessions for one Trust varied in scope and content and developed into journal club support for occupational therapists. Table 1 describes the types of services provided within each of the groups served.

METHODS

The formal evaluation plans were established shortly after the clinical librarian started in the position in September 2003, but formal ethical approval was not obtained until March 2004. Several methods were used to provide in-depth longitudinal evaluation. The clinical librarian kept a reflective practice diary throughout the period of the evaluation (November 2003–January 2005). A reflective diary aims to provide a record of the feelings, actions, reflections, and outcomes of reflections on professional development [7]. The diary entries were sent to a member of the evaluation team, who entered the text documents into qualitative data analysis software to help analyze the librarian's perceptions regarding changes in attitudes within each team. Informed consent forms were distributed with the baseline questionnaire (and by arrangement later).

North East Wales and Conwy & Denbighshire evaluation components

The evaluation for teams in North East Wales and Conwy & Denbighshire comprised baseline and final questionnaire surveys, with interviews conducted between the questionnaire surveys. An initial baseline questionnaire survey in April 2004, six months after the service started, assessed attitudes towards searching electronically (Internet and clinical knowledge databases) and willingness to spend time searching on various types of tasks (Appendix 2; online only). Questions on attitudes and perceived skills were based on the questions used in the INFORMS survey [8], originally developed for information literacy assessment among undergraduates in the UK. One of the questions for the evaluation examined the change in profile of the searching patterns, as it could be important for the clinical librarian to concentrate on the searches that might take longer. Respondents addressed questions about searching that accounted for need parameters (e.g., Question 4 was prefaced by the explanation, “You may sometimes have to check some information about patient care. You may require the information URGENTLY and SPECIFICALLY for the care of an individual patient but that information may not be GENERALLY IMPORTANT for the care of other patients. Sometimes the information is of PERSONAL INTEREST to you as you need it for course work, CPD or research”). The differentiation of the categories was based on evidence that the urgency of a patient problem may govern the decision to search for information [9–10], and that education and research reasons are often intertwined very closely with reasons for seeking information for patient care [11].

The evaluation team also conducted interviews (face-to-face: n = 7; telephone: n = 26) with members of the teams to gather additional data regarding the effects on clinical practice of information provided by the librarian. The interviews were carried out between July and October 2004 and their duration varied between 20 and 45 minutes. A random sample was taken of the members of the teams who had access to the clinical librarian services (n = 94), stratified by team with proportionally more in the sample for the larger teams than for the smaller teams. After obtaining informed consent from interviewees, the interviewer employed a script (Appendix 3; online only). The interviewer (JT) had previous experience in health service research and recent experience of interviewing higher and further education staff and students. The interviews complemented the information obtained from the feedback forms returned with the questionnaires. The questions (on the feedback form and in the interviews) on the impact on clinical knowledge and decision-making were based closely on those used in the Value project [11–12], which have been used in other clinical librarian evaluations in the UK [13].

The final questionnaire survey in December 2004 (Appendix 4; online only) was the same as the baseline questionnaire, but omitted one general question about Internet use and added questions concerned with willingness to delegate searching to the clinical librarian and perceived priorities for various library services, including services offered by the clinical librarian. In addition, the evaluation team analyzed feedback from clinical staff on the literature searches conducted by the clinical librarian for them (a feedback form was included with each set of search results; see Appendix 5; online only).

North West Wales evaluation components

Evaluation of the information skills outreach training sessions in North West Wales involved informal pre- and post-session skills assessment conducted by the clinical librarian. The evaluation team also conducted interviews with twelve training participants to assess the impact of training on practice; these interviews employed questions similar to a questionnaire sent out one month after training (Appendix 1; online only). A convenience sample of twelve was taken from a list of participants who had agreed to be interviewed.

Statistical analysis

The questionnaire data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet for simple descriptive statistical analysis. The interview data were entered into a qualitative data analysis software package (QSR N6). The qualitative analysis aimed to identify and explain the reasons for changes in team member attitudes towards searching for information, use of the clinical librarian, the time spent on various types of clinical questions, and any impact clinical librarian services may have had on clinical practice.

RESULTS

Response rate

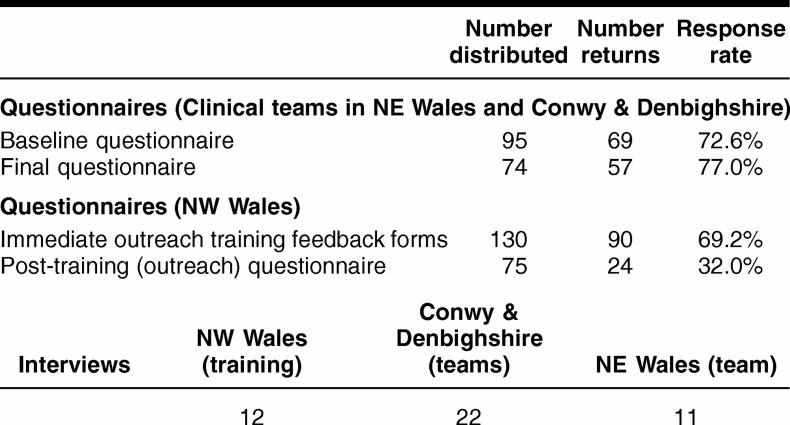

As indicated in Table 2, the response rate to most of the questionnaire surveys varied from 69–82%, with the exception of the post-training questionnaire (n = 24, 32% response rate). Interviews revealed that some of those trained had not put their skills into practice. If so, that might explain the poor response as questionnaire recipients might believe they could not contribute usefully. Few staff returned the feedback forms included with the literature search results (response rate 15.6%, 34/218); this data was supplemented by questions on the impact on clinical practice included in the interviews.

Table 2 Evaluation survey response

Overview: realizing benefits while changing practice

Interviews in all sites revealed the problem of balance between the clinical librarian doing searches for clinicians and making clinical staff more effective independent searchers. The changes in information-seeking behavior and attitudes towards search delegation illuminate this dilemma, but it is important to emphasize that the service evolved during the evaluation and that lessons learned at one of the sites were used to solve problems at another.

Reflective practice diary

The reflective diary data recorded how the clinical librarian's activities gradually changed according to the demands and needs of clinical staff, particularly in the community. As she gained their trust, her role evolved from “not yet thought of as an ‘integral’ member of the team” to her feelings that she was “making a positive impact with this team.”

As the clinical librarian's role developed, the administrative elements (e.g., time spent scheduling meetings) were reduced, or at least streamlined, with far more time spent on literature searching and training towards the end of the evaluation, and less time spent on administration or attendance at clinical meetings.

North East Wales and Conwy & Denbighshire findings

Literature searching feedback

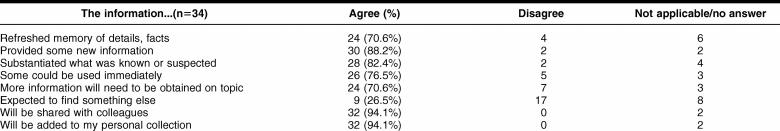

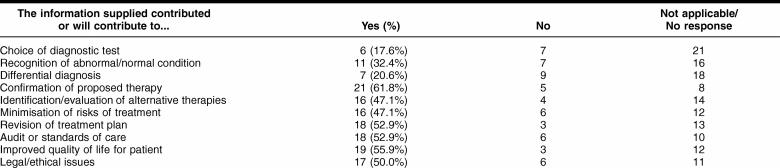

All the teams (apart from the Community/Training team in North West Wales) initially asked the clinical librarian to carry out individual searches. The number of searches requested by different teams varied. The total number of searches (Sep 2003–Dec 2004) was 218 (13.6 per month), but the average rate per month in the last 6 months of the project was 15 to 16 per month. The impact of the clinical librarian services was derived partly from the 34 literature searching feedback forms and supplemented by details obtained from the other questionnaire instruments and the interviews. The immediate cognitive impact was reflected in responses indicating that some of the information supplied was new, although some confirmed what was suspected and refreshed the memory about particular details (Table 3). Some of the information was in most cases immediately applicable, and participants indicated that the results would almost always be shared with colleagues. The impact on clinical decision-making was most commonly associated with checking that a proposed therapy or treatment plan was the best choice, and just over 50% of the searches resulted, or might in the future result, in changes to the treatment plan (Table 4).

Table 3 Immediate cognitive impact of information supplied in literature searches (data extracted from feedback forms for individual searches, n = 34)

Table 4 Impact on clinical decision making of information supplied in literature searches (data extracted from feedback forms for individual searches, n = 34)

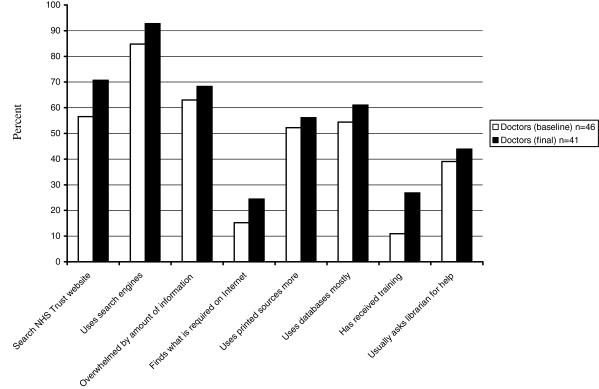

Questionnaire findings: changes in information behavior

The final survey was answered by 57 participants, though respondents did not answer all questions. In the final survey, 70.7% of the medical staff (n = 41) reported using NHS and library Websites, a higher proportion than in the baseline survey (59.4%, n = 69). A higher proportion felt overwhelmed by the amount of information retrieved (68.3%) than at baseline (60.9%, n = 69). Although only 26.8% reported having received library skills training on the final questionnaire, this is much higher than the baseline figure of 10.9% (Figure 1). There was a slight shift upwards in Internet searching skills, with nobody in the final survey reporting no experience. It should be stressed that the composition of the baseline and final groups was not the same, because many of the junior doctors at the baseline stage had moved to other posts by the time the final phase started. The changes in information resource use among nurses and other non-medical staff (n = 23 baseline, n = 12 final) were less pronounced.

Figure 1.

Baseline and final attitudes of doctors towards searching (clinical teams, NE Wales and Conwy & Denbighshire)

At baseline, medical staff were unwilling to spend a long time searching for information, and most searches were expected to last less than 10 minutes. If the search was of personal interest, more doctors indicated that they were prepared to spend a relatively longer time searching. After introduction of the clinical librarian service, doctors (the largest group of staff surveyed) were prepared to spend more time searching for specific, urgent queries concerning patient care. At baseline, the modal search duration was less than 10 minutes (48%, 22/46), whereas in the final phase the modal search duration was between 10 and 30 minutes (44%, 18/41), and doctors were also prepared to spend more time searching for queries of general importance for patient care. For example, 54% (25/46) were prepared to spend less than 10 minutes at baseline for searches that were of general importance but not of personal interest, but the corresponding percentage at the final stage was 36% (15/41). The patterns make sense if it can be assumed that searches of personal interest are likely to be sustained longer than searches that are not of personal interest.

The presence of the clinical librarian also appeared to affect personal searching behavior as doctors were also prepared to spend longer on searches of personal interest, a finding that was not expected. At baseline, 13% (6/48) of doctors were prepared to spend more than an hour searching for personal interest only, while in the final phase, 27% (11/41) were prepared to spend that amount of time searching.

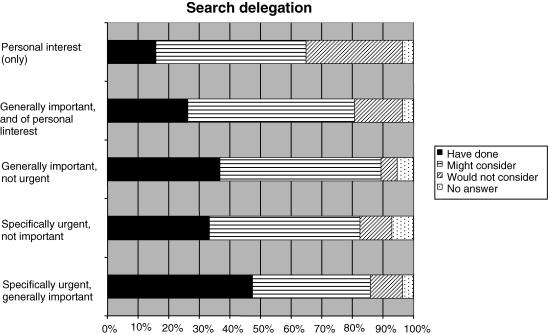

The final questionnaire also asked the teams how willing the respondents (n = 57) would be to delegate searches to a clinical librarian. The type of search was categorized according to urgency, importance, and personal interest. Results (Figure 2) show that nearly half of the respondents had already delegated searches that were specifically urgent (for an individual patient) and important for patient care in general. However, over 50% (n = 30) might consider delegating searches that were important for patient care in general, but not urgent. Team members were less willing to delegate searches that were of some personal interest to them, and fewer had in fact delegated searches of this nature. Over 50% (n = 31) might consider delegating such searches if they were also of importance to patient care in general, indicating a considerable potential demand for such searching.

Figure 2.

Willingness to delegate searches to a clinical librarian (n = 57, final questionnaire, NE Wales and Conwy & Denbighshire)

Interview findings: changes in clinical practice

Interviews with clinical teams (n = 33) provided examples of changes in practice beyond the immediate cognitive impact indicated from the literature searching feedback forms.

In the interviews with the teams, 85% (n = 28) of the interviewees stated they shared the information found by the clinical librarian with colleagues, 12% (n = 4) reported that the information was shared widely with other staff, and 10% (n = 3) shared with patients. Interviews confirmed that the main impact on clinical practice was on patient management and therapy. None of the interviewees considered that the information found aided diagnosis, but most of the searches contributed towards patient management and/or therapy (76% (n = 25) indicated effects on patient management, and 55% (n = 18) on therapy), partly by providing confidence that clinical decisions were correct and based on the best evidence available at the time. One interviewee, an occupational therapist, identified the benefit of librarian-provided information as:

enabling us to be more effective and more concise in the report that we're creating at the moment. But also in the future from a perspective of using the most recent information available so that we're doing the most up-to-date therapy with clients, and providing the most up-to-date information material with clients.

Seven interviewees (21%) thought that the information found would contribute towards a publication (in the CAP (Community Assessment Partnership), Lung, Nutrition and Psychiatry groups). The CAP, ICU, Nutrition, and Psychiatry groups in particular had used or were intending to use the information for presentations (in all, 55% (n = 18) of those interviewed). Almost all the interviewees in the CAP, Nutrition, and Psychiatry groups commented that the information found would contribute towards continuing professional development (CPD), as did more than half in the Lung and Urology groups (in all, 79% (n = 26) of interviewees).

In one instance, cost savings were identified by a consultant, in the avoidance of unjustified expenditure.

One piece of information that we were looking at was on looking at a new method of airway control in the anaesthetized patient. And it was quite an expensive way, an expensive piece of equipment … we decided that it probably wasn't something that needed to be for every patient and that there were training issues involved in it and there was more work that needed to be done before we could actually introduce it. So it stopped us buying something straight away that we might have bought and not utilized to the full.

Interviews: changes in information behavior

Fifteen (45%) of the team members interviewed (n = 33) stated that their searching skills had improved since using the services of the clinical librarian. The clinical librarian service may or may not have been responsible for the changes, but the interviews helped to explain the observations and suggested that there had been a change in team culture in some teams. As one consultant noted regarding the influence of the clinical librarian: “She hasn't saved us time, she's actually increased our education time, no, she's made better use of the educational time that we already had.”

With the journal clubs in the clinical teams, the clinical librarian served as a liaison with the consultant in charge to develop structured training sessions for the junior doctors (to be carried out in advance of their journal club presentations). Junior doctors commented favorably on this support. One junior ICU doctor commented: “Yes, my searching skills have dramatically improved! Drastically improved I would say!”

Interview feedback also indicated that the journal clubs were transformed into sessions that were more worthwhile to attend. One ICU consultant noted that the librarian's collaboration aided

hugely, because now meetings which we didn't particularly like going to before, now are a sell-out. They're very well attended. People talk very frankly and they talk from facts, rather than from opinion, and they learn.

North West Wales findings

Outreach training

The outreach training sessions were rated highly immediately after the sessions, with almost all (99%) session respondents (n = 130) agreeing that the objectives were clear and that the clinical librarian presented the material effectively. The expectations were clear for 72.2% (n = 94) of the respondents, and comments indicated that the content and balance were appropriate. Particularly helpful aspects were the practical, hands-on element and learning how to search effectively and efficiently. The sessions left 88.9% (n = 116) of the respondents more confident, and an equal percentage had had their expectations of the course met. The main demand remaining after the training was for more follow-up sessions, with hands-on practice.

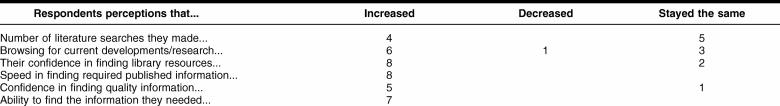

The post-training questionnaire 1 month later indicated that 54.2% of respondents (13/24) believed their searching skills had improved. Interviews (n = 12) over 1 month later confirmed that initial enthusiasm had usually tapered off, and interviewees were unsure whether they were more efficient or effective in their searching. Attitudes had improved overall, however (Table 5). Representative comments included:

I do spend more time searching. Previously I used to do one search and then perhaps I wouldn't be able to get what I wanted so I had to go to my librarian. (physical therapist commenting on the effectiveness of searching skills training)

Oh a difficult one, I don't know really. I'd have to think about that. Because although you might spend more time searching, you might just be widening the net a bit mightn't you, so it's a difficult one really. I'm not sure. (senior nurse commenting on uncertainty regarding efficiency and effectiveness)

Table 5 Changes in searching habits reported by interviewees (n = 12) one month post training in North West Wales

Among the training group, 8 of the 12 interviewees (66.7%) noted instances of improved searching following training. Towards the end of the project, the clinical librarian was asked to start journal clubs for some of the therapists in the area served by outreach training. An occupational therapist whose main contact with the clinical librarian was through a journal club commented that her confidence had increased particularly because of the regular contact:

Unless you have a regular way of using the information that you've gleaned through a one-off course, your ability to use the information atrophies. And that's one of the brilliant things about working with [the librarian] is because it's a regular thing, because it's regular support and you're developing skills that she's teaching or you're developing something that you learnt before. It's the opportunity to apply the information.

However, this type of journal club support was an activity that may be temporary, with the clinical librarian helping to establish and structure the way of working, and then moving on to other activities. In this case, another journal club for palliative care was established. The focus later changed, after the evaluation, to helping to produce a resource pack for preventing patient falls as part of a fall prevention strategy for the hospital Trust.

Perceptions of future development of the clinical librarian service

All interviewees from the clinical teams (NE Wales and Conwy & Denbighshire) were asked how they would like to see the service develop in the future. The responses were fairly evenly split among making the service more accessible to others, providing more searching skills training for staff (to lessen dependence on the clinical librarian), and keeping the service as it was. Some team members commented on the fine balance between being more skilled themselves in searching and knowing when to delegate searches to the clinical librarian:

In a way it would make more sense if she could teach us to do some things ourselves, you know like the simple things. And then use her time for the more complex things because that might be a better use of her time, you know, with the sort of dinosaurs like me and probably other consultants. But I've always found her very available and speedy so I can't think of any criticisms. I can't think of any improvements. (consultant psychiatrist)

At the start of the project, the librarian support given to the journal clubs within clinical teams and the training sessions held in North West Wales were viewed as completely separate types of activities. Towards the end of the project, both sets of activities were becoming similar.

DISCUSSION

One of the aims of this evaluation was to indicate how clinical librarians could be used within health library services in Wales. The clinical librarian served around 100 staff within the clinical teams, with more staff reached during the formal training sessions. The evaluation findings indicate changes in information behavior among the teams, as well as the effectiveness of the journal club support.

The original plan envisaged a baseline survey at the start of the project, but delays in obtaining ethical approval meant that the baseline survey was conducted four months later than planned. However, there were changes in team behavior observed from the quantitative surveys (baseline to final). Although some of the changes observed might have been the result of changes in composition of the staff teams, the qualitative analysis supports the quantitative findings. Interviews were held with a randomly selected third of the staff in the clinical teams during the middle to final stages of the project; nearly all those selected for interview agreed to be interviewed, likely reducing the possibility of response bias in this portion of the evaluation. A controlled before and after type of study, following clinical teams with and without a clinical librarian, would have helped to clarify the type and scale of impact the clinical librarian made on searching attitudes and skills.

Several clinical librarian projects have focused on mediated searching, but this research indicates that the substitution of a clinical librarian for health professionals in executing searches is only part of the picture. The results show that including a clinical librarian on a team appears to increase the willingness of staff to spend time searching themselves. Willingness to spend more time searching may be governed by the likelihood of finding a good answer [12], and the clinical librarian may have demonstrated that good answers can be found. On the other hand, having the clinical librarian on the team also increases the willingness to delegate searching. Perhaps there is a block of “reading time” that health professionals view as inelastic. This reflects the findings of Tenopir [14] that the time spent by medical faculty on journal reading has changed slightly but not as much as the number of readings. There may be a limit to the possible benefits in terms of time savings that a clinical librarian service based on the mediated literature searching model might achieve, as the current results indicate that doctors may spend more time reading themselves, as well as delegating some searches.

However, the outputs of searches by clinical librarians and health professionals may differ. The qualitative findings indicate that the searches done by the clinical librarian were generally more comprehensive, in the opinion of the interviewees. The evaluation could not examine objectively how much less or more time the clinical librarian spent on a search versus a health professional doing the same search, but the interviews revealed that health professionals believe that the clinical librarian searches were usually as effective and performed far more efficiently, and probably more comprehensively, than clinician-executed searches.

One problem in clinical practice is that there are usually far more clinical questions to be pursued than are actually pursued [15]. A qualitative study of residents' experience in answering clinical questions indicated a complex mix of individual and organizational barriers that may lead junior doctors to abandon searches [16]. Not surprisingly, there is no consensus on the number of clinical questions that, on average, should be pursued in different types of clinical practice, and a highly pressured working environment is likely to provide neither opportunities to pursue clinical questions nor the time to reflect on the answers that a clinical librarian could provide. This implies that clinical librarian services must be tailored carefully to the opportunities that arise for more effective user education or clinical questions that really matter to health service delivery.

Journal clubs offer the opportunity for structured support by providing teaching that is integrated into clinical practice. A systematic review also confirms that such structured support is more effective than stand-alone, non-integrated teaching in postgraduate education [17]. This type of active intervention by the clinical librarian differs from the supporter role in literature searching. A review of strategies for answering clinical questions in primary care suggests that clinical librarian services could be Web-based, with the clinical librarian acting in response to a question by a primary care physician [18]—a remote support role for literature searching; nonetheless, it could offer added synthesis value over the traditional reference service and be provided at the speed required. The setting is different but the dilemma is traditional—should the clinical librarian's effort be devoted to the synthesis, or to structured education of the clinician in finding the evidence, or to a mixture of both?

Generalizing the results of this evaluation to other settings may be difficult, as the scope of the activities was probably much larger than in other clinical librarian projects in the UK [5] and the geographic area covered certainly more extensive. This made it possible to detect some patterns in which strategies worked and which were less effective. The changes that occurred within the teams [19] were reflected in the different searching patterns, and attitudes from the questionnaires and the team culture changes could be potentially reflected in the willingness to spend time searching. However, the scope of the clinical librarian's work changed during the evaluation, and there may have been insufficient time to fully develop some aspects of the work.

CONCLUSION

The North Wales evaluation illustrated how information behavior and professional practice changed among the teams served, and the findings, although they cannot be conclusive, suggest that the presence of the clinical librarian increased the willingness of staff to search for information, as well as encouraging them to delegate searches to the clinical librarian. These findings have implications for cost-benefit analyses of clinical librarian projects. The findings suggest that structured support, through journal clubs and training support that is linked directly to clinical and educational needs, does enhance journal club or team discussions about improvements to health service delivery. Future research may need to assess any long-term changes in attitudes among staff who participated in this type of journal club, compared with those who participated in journal clubs without clinical librarian support.

For health library managers, the study indicates that health library services can be targeted effectively at particular groups, and that there is an impact on patient care that can be measured, qualitatively if not quantitatively. More research is necessary to characterize the particular attributes of clinical teams that make them more likely to benefit from clinical librarian support.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the health professionals who assisted in the evaluation and the library managers (Eryl Smith, Anne Jones, Richard Bailey) who supported the evaluation. The authors are very grateful for the helpful and constructive comments provided by the referees and the editorial team.

REFERENCES

- Wagner KC, Byrd G. Evaluating the effectiveness of clinical medical librarian programs: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Libr Assoc. 2004 Jan; 92(1):14–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winning MA, Beverley CA. Clinical librarianship: a systematic review of the literature. Health Info Libr J. 2003 Jun; 20(suppl 1):10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weightman A, Williamson J. The value and impact of information provided through library services for patient care: a systematic review. Health Info Libr J. 2005 Mar; 22(1):4–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant S, Harrison J. Clinical librarianship in the UK: temporary trend or permanent profession? Part I: a review of the role of the clinical librarian. Health Info Libr J. 2004 Sep; 21(3):173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward L. A survey of UK clinical librarianship: February 2004. Health Info Libr J. 2005 Jan; 22(1):26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant S, Harrison J. Clinical librarianship in the UK: temporary trend or permanent profession? Part II: present challenges and future opportunities. Health Info Libr J. 2004 Dec; 21(4):220–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath H. Keeping a reflective practice diary: a practical guide. Nurse Educ Today. 1998 Oct; 18(7):592–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INFORMS project. Online questionnaire (used at Oxford). [Web document]. Huddersfield: University of Huddersfield, 2003. [cited 28 Dec 2005]. <http://inhale.hud.ac.uk/informs/surveys/oxstume1.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman PN, Helfand M. Information seeking in primary care: how physicians choose which clinical questions to pursue and which to leave unanswered. Med Decis Making. 1995 Apr–Jun; 15(2):113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MS, Ross FV, Adams DL, and Gilbert CM. Effect of online literature searching on length of stay and patient care costs. Acad Med. 1994 Jun; 69(6):489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart CJ, Hepworth JB. The value to clinical decision making of information supplied by NHS library and information services. [Web document]. British Library R&D report 6205. London: BLR&DD, 1995. [cited 17 May 2006]. <http://users.aber.ac.uk/cju>. [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart CJ, Hepworth JB. The value of information supplied to clinicians by health libraries: devising an outcomes-based assessment of the contribution of libraries to clinical decision-making. Health Libr Rev. 1995 Dec; 12(4):201–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University Hospitals Leicester NHS Libraries. Clinical Librarian Services: Internal evaluation. [Web document]. Leicester, UK: University Hospitals NHS Trust, NHS Libraries, 2006. [rev. 11 Feb 2006; cited 17 May 2006]. < http://www.uhl-library.nhs.uk/clinical_librarian/internal_evaluation.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Tenopir C. Use and users of electronic library resources. Washington, DC: Council on Library and Information Resources, 2003:20–1. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A. The body in question. Health Info Libr J. 2005 Jun; 22(2):150–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green ML, Ruff TR. Why do residents fail to answer their clinical questions? A qualitative study of barriers to practicing evidence-based medicine. Acad Med. 2005 Feb; 80(2):176–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coomarasamy A, Khan KS. What is the evidence that postgraduate teaching in evidence based medicine changes anything? A systematic review. BMJ. 2004 Oct; 329(7473):1017–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coumou HCH, Meijman FJ. How do primary care physicians seek answers to clinical questions? A literature review. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006 Jan; 94(1):55–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart C, Turner J, Durbin J, and Ryan J. Evaluating the contribution of the clinical librarian to a multidisciplinary team. Libr Info Res. 2006 Spring; 30(94):30–43. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.