Abstract

Background: Surgery is the treatment of choice in echinococcal cysts with cystobiliary fistulas. PAIR (puncture, aspiration, injection, and reaspiration of scolecidals) is contraindicated in these cases.

Aim: To evaluate a modified PAIR method for percutaneous treatment of multivesicular echinococcal cysts with or without cystobiliary fistulas which contain non-drainable material.

Patients: Twelve patients were treated: 10 patients with multivesicular cysts which contained non-drainable material and were complicated by spontaneous intrabiliary rupture, secondary cystobiliary fistulas, cyst infection, or obstructed portal or hepatic veins; and two patients with large univesicular cysts and a ruptured laminated membrane, one obstructing the portal and hepatic veins and one a suspected cystobiliary fistula.

Methods: The methods used, termed PEVAC (percutaneous evacuation of cyst content), involved the following steps: ultrasound guided cyst puncture and aspiration of cyst fluid to release intracystic pressure and thereby to avoid leakage; insertion of a large bore catheter; aspiration and evacuation of daughter cysts and endocyst by injection and reaspiration of isotonic saline; cystography; injection of scolecidals only if no cystobiliary fistula was present; external drainage of cystobiliary fistulas combined with endoprosthesis or sphincterotomy; catheter removal after complete cyst collapse and closure of the cystobiliary fistula.

Results: In all 12 patients initial cyst size was 13.1 (6–20) cm (mean (range)). At follow up 17.9 (4–30) months after PEVAC, seven cysts had disappeared and five cysts had decreased to 2.4 (1–4) cm (p=0.002). In eight patients with multivesicular cysts, a cystobiliary fistula, and infection, cyst size was 12.5 (6–20) cm, catheter time 72.3 (28–128) days, and hospital stay 38.1 (20–55) days. At 17.3 (4–28) months of follow up, six cysts had disappeared and in two cysts residual size was 1 and 2.9 cm, respectively (p=0.012). In four patients without a cystobiliary fistula, cyst size was 14.4 (12.7–16) cm, catheter time 8.8 (3–13) days, and hospital stay 11.5 (8–14) days. At 19.3 (9–30) months of follow up, one cyst had disappeared and three cysts were 85 (69–94)% smaller (2.2 (1–4) cm) (p=0.068).

Conclusion: PEVAC is a safe and effective method for percutaneous treatment of multivesicular echinococcal cysts with or without cystobiliary fistulas which contain non-drainable material.

Keywords: cystic echinoccosis; intrabiliary rupture; cyst infection; puncture, aspiration, injection, reaspiration; percutaneous evacuation

PAIR (puncture, aspiration, injection, and reaspiration of a scolecidal agent) of echinococcal cysts in the liver is an invasive procedure with a low complication rate (10%), a high success rate (>95%), and a low relapse rate (<4%).1–4 PAIR is safe and simple to perform even in poorly equipped clinics in developing countries.5 In comparison with albendazole treatment, PAIR was superior, and in experienced hands PAIR is an effective and safe alternative to surgery.6, 7

Usually, PAIR is advocated for uncomplicated univesicular cysts (Gharbi types 1 and 2) although experts also use it for multivesicular so-called “mother and daughter” cysts (Gharbi type 3).1, 7, 8 Each daughter cyst has to be punctured separately which is labourious and inconvenient for the patient. Therefore, an alternative method was developed, the catheterisation technique, in which multivesicular cysts are irrigated with scolecidals to destroy the daughter cysts and laminated membrane.9 Saremi described a percutaneous drainage method which is essentially different from PAIR and the catheterisation technique. In this technique, a special cutting instrument is used to fragment and evacuate daughter cysts and laminated membrane while the cavity is continuously irrigated with scolecidals.10 Both in PAIR and the catheterisation technique, the ruptured daughter cysts and laminated membrane remain inside the cavity. However, using scolecidals, none of these three methods can be safely used for the treatment of cysts with a cystobiliary communication.

We report the first short term results of percutaneous evacuation of multivesicular echinococcal cysts with a cystobiliary communication, using a modified PAIR method. This innovative method has two major advantages. Firstly, it can be used safely in cystobiliary fistulas because scolecidals are avoided. Secondly, it is not necessary to puncture each individual daughter cyst. Cyst content is simply aspirated and evacuated via a large bore catheter. We call this method PEVAC (percutaneous evacuation of cyst content).

METHODS

In all patients, the diagnosis of echinococcal cyst was based on history, physical examination, ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) scan, and serology, and confirmed by microscopy of cyst fluid. Ultrasound, CT scan, and serology were used for follow up. All patients were treated with albendazole (median 11 weeks; range 3 days–2 years) before referral to our centre. When albendazole treatment had not been initiated, we started albendazole before the procedure and continued it for six months after the procedure at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day without interruption.

Inclusion criteria

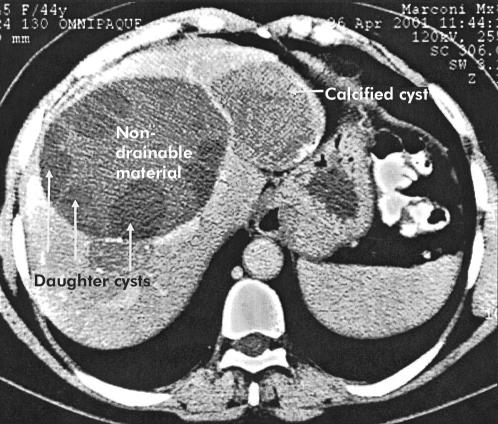

Patients with multivesicular echinococcal cysts (Gharbi type 3) with or without a cystobiliary fistula and containing non-drainable debris were included (fig 1 ▶). Patients with univesicular cysts (Gharbi types 1 and 2) were included only if there was a cystobiliary communication or compression of the hepatic or portal veins or bile ducts. Exclusion criteria were: age <18 years or >75 years; no informed consent; serious coagulation abnormalities; known allergy to local anaesthetics or albendazole; pregnancy or women who refused contraception for the time of albendazole treatment; and cysts characterised by a heterogeneous complex mass (Gharbi type 4) or a calcified wall (Gharbi type 5 ).

Figure 1.

Echinococcal cyst with daughter cysts in the periphery and centrally located non-drainable material.

The drainage procedure is performed in an interventional radiology suite, appropriately equipped and staffed for emergency situations. The patient has an intravenous canula and is continuously monitored with pulse oximetry. After the procedure, the patient is admitted to the medical ward and checked at hourly intervals until the morning after the procedure.

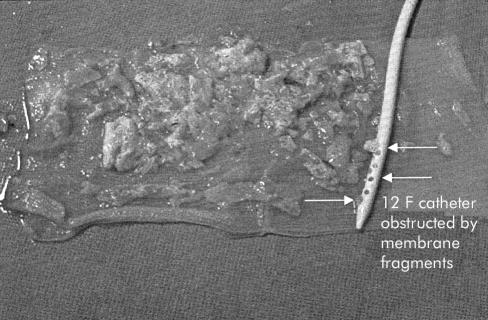

The optimal route for puncture of the echinococcal cyst is determined by CT and US. After intravenous sedation with 2.5 mg midazolam and 0.1 mg fentanyl, and local anaesthesia with 10–15 ml lidocaine 2%, the cyst is punctured under US guidance. Then, to prevent leakage, as much cyst fluid as possible is aspirated to decrease intracystic pressure. A sample of the aspirated cyst fluid is used for parasitological investigation and bacterial culture. Viability is assessed by observing protoscolices motility by direct microscopy and by neutral eosin staining. Subsequently, using the Seldinger technique, a 10–12 French gauge (F) catheter with multiple sideholes is inserted into the cyst cavity after dilating only the skin and proximal intrahepatic part of the puncture tract, again to prevent leakage. The catheter position is confirmed by fluoroscopy. By repetitive manual injection and reaspiration of small amounts (5–10 ml) of isotonic saline, the remaining liquefied part of the mother cyst is removed. The catheter is left in place for drainage. In a second session the catheter is replaced with a 14–18 F stiff Amplatz sheath (William Cook, Bjaeverskov, Denmark). A suction catheter is introduced into the cyst cavity through the sheath and the cyst content is evacuated by directing the catheter towards the daughter cysts, endocyst, and non-drainable material, and applying suction (fig 2 ▶). After removal of the sheath a catheter of the same French size as the sheath is placed and contrast is injected into the cyst cavity to detect a possible communication with the biliary tree. In the case of a cystobiliary fistula, an endoprosthesis is introduced endoscopically into the common bile duct (CBD). Sphincterotomy is performed when membrane fragments have to be removed from the CBD or when stenting does not adequately decrease intraductal pressure. Finally, the catheter is removed after complete cyst collapse and closure of a possible cystobiliary fistula, indicated by a daily catheter output of <10 ml.

Figure 2.

Fragments of daughter cysts and endocyst evacuated through the sheath with a 12 French gauge catheter.

After the procedure is completed, cyst size is monitored by US at two weeks and 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after PEVAC. If clinically indicated, US is repeated at shorter intervals. CT scans are performed 12 and 24 months after drainage. The primary end points were defined as complete cyst collapse at US at the end of the procedure, disappearance of cyst cavity or at least 50% reduction in cyst size at follow up imaging, and disappearance of complications such as pain, cystobiliary fistulas, vascular or biliary compression, and infection. Direct treatment results were evaluated at the end of the procedure: early results at six months and late results two years after PEVAC. The secondary end points of the study were recurrence of cyst cavity to >50% of its initial size, vascular or biliary compression, fistulas, pain and infection within two years after PEVAC, and death, withdrawal from the study, or loss to follow up. Three examples of cyst appearance before and after PEVAC are shown in figs 3–5 ▶ ▶ ▶.

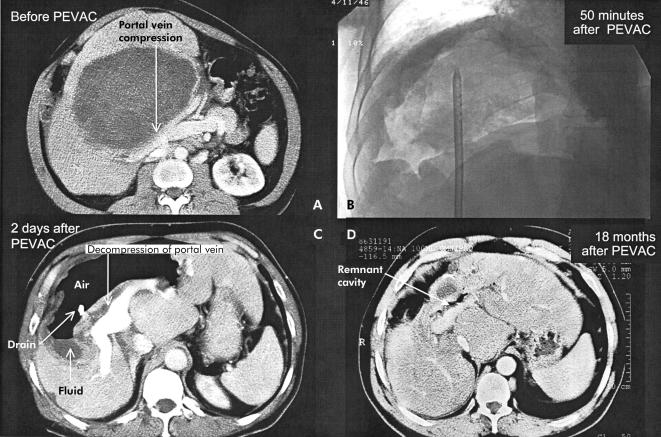

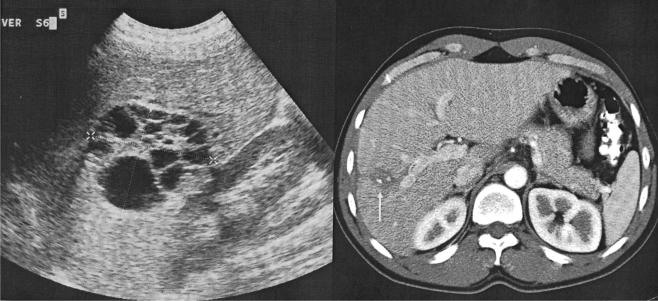

Figure 3.

Computed tomography (CT) scan before percutaneous evacuation (PEVAC) showing portal vein bifurcation compression by “mother and daughter” cysts (A). (B) Cyst cavity 50 minutes after partial evacuation of cyst content. (C) CT scan two days after PEVAC showing decompression of portal vein bifurcation and air fluid level in a non-collapsed cavity. (D) CT scan 18 months after PEVAC showing the remnant cavity.

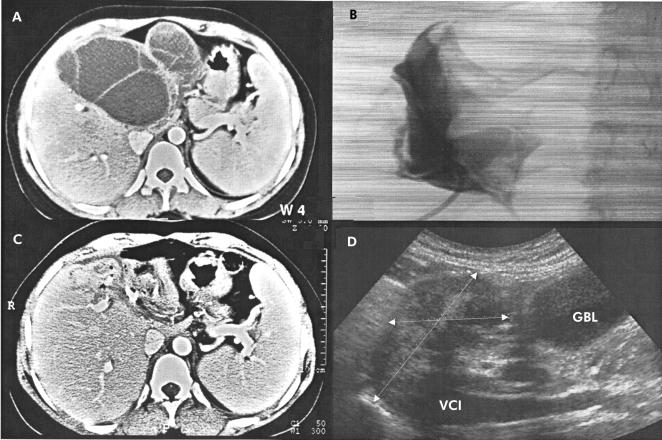

Figure 4.

Computed tomography (CT) scan before percutaneous evacuation (PEVAC) (A). Cystography after partial evacuation of cyst content on day 1 (B) and CT scan on day 2 (C) showing partial cyst collapse. Four months after PEVAC, ultrasound shows remnant cavity near the gall bladder (GBL) and inferior caval vein (VCI) (D).

Figure 5.

Ultrasound before percutaneous evacuation (PEVAC) of multivesicular cyst which had spontaneously ruptured into the biliary tree (left). Computed tomography scan 13 months after PEVAC shows (arrow) partially calcified cyst remnant (right).

PEVAC treatment was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Statistics

The Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to compare results between patient groups and the Wilcoxon signed ranks test for paired observations within patient groups (SPSS for Windows).

PATIENTS AND RESULTS

Patients

Twelve patients with hepatic echinococcosis, mean age 38 years (range 22–61), immigrants from Morocco (five), Turkey (three), Pakistan (one), Syria (one), Afghanistan (one), and Greece (one) were treated for recurrent and severe upper abdominal pain. Ten patients had multivesicular so-called “mother and daughter” cysts (Gharbi type 3) containing non-drainable material. Two patients had univesicular cysts (Gharbi type 1) with a ruptured laminated membrane. In one, the right hepatic and portal veins were compressed by the cyst. In the other patient, the univesicular cyst, which did contain one daughter cysts, was suspected of having a cystobiliary communication.

Complications

Cystobiliary fistulas and infections were the main complications, which occurred only in patients with multivesicular cysts. Less frequently observed complications were significant obstruction of portal and/or hepatic veins in three patients and perforation of a gastric ulcer into the cyst in one patient. Allergic reactions (transient fever, skin rash, eosinophilia) due to leakage of cyst fluid were observed in three patients following changing or removal of the catheter.

Three patients presented with spontaneous intrabiliary rupture. In five other patients the cystobiliary fistula became radiologically apparent on days 8, 17, 20, 25, and 53, respectively, after starting PEVAC. All but one cystobiliary fistula were endoscopically treated by introducing an endoprosthesis into the CBD or by sphincterotomy. In one patient a small cystobiliary fistula closed spontaneously (table 1 ▶).

Table 1.

Decrease in cyst size at follow up after percutaneous evacuation (PEVAC), catheter time (days), and hospital stay, related to the occurrence of cystobiliary (CB) fistulas plus cyst infection in patients with multivesicular echinococcal cysts in the liver. In patient No 8, cyst content was partially evacuated. Patient Nos 9 and 10 had univesicular cysts

| Patient No | Cyst size before PEVAC (cm) | Cyst size after PEVAC (cm) | Catheter time (days) | Hospital stay (days) | Follow up (month) |

| 1* CB | 11 | 0 | 43 | 38 | 14 |

| 2† CB | 6.6 | 0 | 126 | 55 | 24 |

| 3† CB | 9 | 0 | 28 | 29 | 28 |

| 4* CB | 6 | 0 | 35 | 41 | 18 |

| 5‡ CB | 14 | 0 | 32 | 35 | 25 |

| 6† CB | 20 | 0 | 113 | 37 | 21 |

| 7‡ | 12.7 | 0 | 13 | 14 | 26 |

| 8 | 13 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 30 |

| 9 | 16 | 1 | 7 | 11 | 12 |

| 10 | 16 | 1.5 | 12 | 13 | 9 |

| 11† CB | 15 | 2.9 | 73 | 50 | 4 |

| 12† CB | 18 | 1 | 128 | 20 | 4 |

| All patients | 13.1 (6–20) | 2.4 (1–4) | 51 (3–128) | 29.3 (8–55) | 17.9 (4–30) |

| CB fistula | 12.5 (6–20) | 1.9 (1–2.9) | 72.3 (28–128) | 38.1 (20–55) | 17.3 (4–28) |

| No fistula | 14.4 (12.7–16) | 2.2 (1–4) | 8.8 (3–13) | 11.5 (8–14) | 19.3 (9–30) |

*Spontaneously or †secondarily infected cysts, or ‡cyst cavity infection after PAIR.

A primary cyst infection was diagnosed in two patients and a secondary cyst infection in seven patients. All patients were successfully treated with antibiotics. In one patient with a primary infection, S milleri and anaerobes were cultured from the cyst cavity. In the other patient, culture was negative due to antibiotic treatment. S morbillorum, S epidermidis, and C freundii were cultured from the cyst cavity in two patients who were readmitted with cyst infection one and five months, respectively, after a PAIR procedure. Remarkably, in both patients bacterial culture of cyst fluid at the end of PAIR was negative.

Contrast injection at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) caused cholangitis and secondary cyst infection in five patients; three also developed a mild transient pancreatitis. S milleri, C freundii, C albicans, S sanguis, K pneumoniae, H influenzae, anaerobes, and enterococci were cultured from their blood, cyst cavity, or bile.

Cyst viability

In the initially sampled cyst fluid of nine patients, viable protoscolices were diagnosed in addition to fragments of the laminated membrane or hooklets. Remarkably, in both patients with multivesicular cysts which became infected following a PAIR procedure, protoscolices were still viable. In two patients with spontaneously infected cysts, viability of daughter cysts could not be assessed because cyst content was too purulent. In one patient with a multivesicular cyst, no protoscolices or hooklets were diagnosed.

Catheter time

In patients with a cystobiliary fistula, catheters were removed 72.3 (28–128) days after PEVAC, 53.6 (7–120) days after endoscopic treatment of the cystobiliary fistulas (mean (range) (table 1 ▶). Hospital stay was 38.1 (20–55) days. In patients without a cystobiliary fistula, catheters were removed after 8.8 (3–13) days and hospital stay was 11.5 (8–14) days. Catheter time and hospital stay were significantly longer in patients with a cystobiliary fistula (p=0.007).

Cyst size

Before treatment, cyst size was 12.5 (6–20) cm in patients with and 14.4 (12.7–16) cm in patients without a cystobiliary fistula (p=0.570). At the end of the procedure, when the catheters were removed, all complaints and complications had disappeared. Cavities had collapsed in all but one patient in whom the daughter cysts were partially evacuated. At follow up, 17.3 (4–28) months after treatment, cyst cavities had disappeared in six of eight patients with a cystobiliary fistula and were reduced to 1 and 2.9 cm, respectively, in the other two (p=0.012). In four patients without a fistula, cyst cavity had disappeared in one and cyst size reduced to 2.2 (1–4) cm in the other three, 19.3 (9–30) months after treatment. This 89 (69–100)% reduction in cyst size was not significant for this small number of patients (p=0.068). When all 12 patients were considered as a group, cyst size was significantly smaller 17.9 (4–30) months after treatment than before: 1.6 (0–7) cm versus 13.1 (6–20) cm (p=0.002). In none of the patients had complaints or complications recurred. No patient died, withdrew from the study, or was lost to follow up.

Serology

In comparison with cyst size, the response of total IgG echinococcal antibody titres was slow and started to occur after about one year. At serological follow up, a sixfold decrease in antibody titres was observed in three patients, a fourfold decrease in two, and no change or a twofold decrease in four patients. A sixfold increase was observed in two patients, one of whom had a marked allergic reaction. Data for one patient are not yet available.

DISCUSSION

Surgery is the treatment of choice for patients with complicated echinococcal cysts in the liver.11 Multivesicular cysts, ruptured into the biliary system, are considered to be contraindicated for percutaneous treatment with scolecidal agents.1 We went beyond the limits of PAIR and treated these complicated cysts percutaneously but avoided the use of scolecidal agents. Elimination of the mass effect by evacuation of cyst content was a prerequisite for success because bile ducts or portal or hepatic veins were compressed and cyst cavities infected. Therefore, we modified the original PAIR method to obtain appropriate access to the cyst cavity and to facilitate evacuation of daughter cysts, laminated membrane, and non-drainable content. By doing so, PEVAC mimics what is achieved at surgical endocyst removal. Unlike surgery, it takes at least two sessions to complete the procedure.

PEVAC is primarily indicated in patients with multivesicular hepatic echinococcal cysts containing non-drainable content, especially in cases of spontaneous intrabiliary rupture or secondary cystobiliary fistulas, vascular or biliary obstruction, or centrally located lesions. In univesicular cysts, PEVAC is only indicated in cases of cystobiliary fistula, or vascular or biliary obstruction. In these latter cases, we consider PEVAC as a safer option than PAIR because possible damage to bile ducts or blood vessels by scolecidals entering the pericyst space is avoided.

Due to the negative selection of patients, pretreatment and post-treatment morbidity was high but comparable with that of surgery. In surgically treated patients with intrabiliary rupture, pretreatment morbidity is characterised by jaundice (56–100%), fever (56–70%), chills (37–56%), and cyst infection (5.4%). In the postoperative period, wound infections (6–15%), pneumonia (3.7–7.5%), liver abscess (2.5%), and allergy were the most frequent complications. Death rate was 1.2–4% and mean hospital stay 19.8–34.6 days.12–15 Not surprisingly, the main complications we noted were cyst infections and cystobiliary fistulas. These complications occurred only in patients with multivesicular cysts and not in those with large univesicular cysts.

Most infections were secondary to a prior intervention. Two patients were readmitted with a cyst infection at one and five months, respectively, after a PAIR procedure. Despite the infection both cysts were still viable. Contrast injection at ERCP also appeared to be a risk for cyst infection. All five patients who underwent ERCP developed cholangitis and cyst infection. In two spontaneously infected cysts, viability and possible infection of daughter cysts could not be diagnosed accurately. PEVAC was performed to support antibiotic treatment.

Three patients presented with a spontaneous intrabiliary rupture and an overt cystobiliary fistula. Of note, in five other patients the cystobiliary fistula became apparent only 1–7 weeks after evacuation of cyst content. Cyst fluid was initially clear but became bile stained in the course of the procedure, in two patients even after about 100 ml were drained. Cystography at the beginning of the procedure could not reliably reveal a cystobiliary communication. The daughter cysts prevented the contrast from reaching the outer limits of the mother cyst. Therefore, care has to be taken with early injection of scolecidal agents into the cavity of multivesicular cysts.

The cystobiliary fistulas were probably firstly masked by the expanded endocyst and subsequently became unmasked by evacuation of cyst content and cyst collapse. However, we cannot exclude the fact that the negative pressure we used to evacuate the laminated membrane contributed to the development of cystobiliary fistulas. In all five patients with secondary fistulas, revealed by contrast injection, initially clear cyst fluid became bile stained in the course of the procedure. In Saremi's method, where the laminated membrane is also evacuated with the use of negative pressure, 34.5% of patients had bile stained drainage fluid and in 15.6% a cystobiliary fistula was demonstrated.16 In PAIR, where no assisted negative pressure is applied and the laminated membrane is not evacuated, lower fistula rates of 1.7–6.2% are observed.17 In the end, in our patients, all eight cystobiliary fistulas closed 53.6 (7–120) days after endoscopic treatment, which is advocated in these cases.18, 19

The allergic reactions observed in three patients were probably due to leakage of cyst fluid after changing and removing the catheter. This illustrates the risk of long term use of large bore catheters, the need to closely monitor the patient at regular intervals, and the need for albendazole treatment after PEVAC to prevent widespread abdominal hydatidosis.

Our policy was to remove the catheter only when the cyst cavity had collapsed and catheter output was <10 ml/day. We reasoned that closure of the cystobiliary fistula and collapse of the cyst cavity would be closely related. Therefore, catheter time and hospital stay were long. In the case of a cystobiliary fistula, catheter time was 72.3 (28–128) days and hospital stay 38.1 (20–55) days; without a fistula, these times were 8.8 (3–13) days and 11.5 (8–14) days, respectively (p=0.007 and 0.007, respectively). This is comparable with a mean hospital stay reported in surgically treated patients with cystobiliary fistulas of 19.8–34.6 days.12–15 Hospital stay in our patients with cystobiliary fistulas might have been shorter if we had accepted some residual cyst size by removing the catheter earlier. Another option is to discharge the patient and monitor closely in the outpatient department, removing the catheter when daily output is <10 ml.

The final result at follow up, 17.9 (4–30) months after PEVAC, was encouraging. Cyst cavities had disappeared or become significantly smaller (p=0.002). The decrease in echinococcal antibody titres was slow, less remarkable, and a significant increase was observed both with and without a marked allergic reaction.

In summary, PEVAC is a safe and effective method for percutaneous treatment of multivesicular echinococcal cysts with or without cystobiliary fistulas which contain non-drainable content, especially in cases of vascular or biliary obstruction. In univesicular cysts, PEVAC is only indicated in selected cases with a cystobiliary communication, or vascular or biliary obstruction. Following PEVAC, cysts disappeared completely or became >60% smaller. Compression of bile ducts and portal or hepatic veins resolved. Cyst infections and cystobiliary fistulas were the main complications. In patients with a cystobiliary fistula, pretreatment and post-treatment morbidity was high and hospital stay was long but comparable with that of surgery. PEVAC may be improved to reduce morbidity and hospital stay. PEVAC will not replace surgery but may simply create access to a less invasive treatment for more patients. Whether PEVAC reduces the relapse rate will need to be demonstrated in future studies. The observation period of our study was too short to draw any conclusions regarding the recurrence rate following PEVAC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor C Filice (University of Pavia, Italy) for his support; Dr T van Gool (Laboratory of Parasitology, AMC) for parasitological examination of the cyst fluid; and Dr AM Polderman (Laboratory of Parasitology, Leiden University Medical Centre) for the serological tests.

Abbreviations

PAIR, puncture, aspiration, injection, reaspiration

PEVAC, percutaneous evacuation

CB, cystobiliary

CBD, common bile duct

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

CT, computed tomography

US, ultrasound

REFERENCES

- 1.Akhan O, Ozmen MN. Percutaneous treatment of liver hydatid cysts. Eur J Radiol 1999;32:76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ustunsoz B, Akhan O, Kamiloglu MA, et al. Percutaneous treatment of hydatid cysts of the liver: long-term results. AJR 1999;172:91–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salama H, Farid A, Strickland GT. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic hydatid cysts with the aid of echo-guided percutaneous cyst puncture. Clin Infect Dis 1995;21:1372–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filice C, Brunetti E, Bruno R, et al. Percutaneous drainage of echinococcal cysts (PAIR-puncture, aspiration, injection, reaspiration): results of a worldwide survey for assessment of its safety and efficacy. Gut 2000;47:156–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filice C, Brunetti E. Use of PAIR in human cystic echinococcosis. Acta Trop 1997;64:95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khuroo MS, Dar MY, Yattoo GN, et al. Percutaneous drainage versus albendazole therapy in hepatic hydatidosis: a prospective, randomized study. Gastroenterology 1993;104:1452–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khuroo MS, Wani NA, Javid G, et al. Percutaneous drainage compared with surgery for hepatic hydatid cysts. N Engl J Med 1997;337:881–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gharbi HA, Hassine W, Brauner MW, et al. Ultrasound examination of the hydatic liver. AJR 1981;139:459–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akhan O, Ozmen MN, Dincer A, et al. Liver hydatid disease: long-term results of percutaneous treatment. AJR 1996;198:259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saremi F. Percutaneous drainage of hydatid cysts: use of a new cutting device to avoid leakage. AJR 1992;158:83–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anonymous. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 29–1999. A 34-year-old woman with one cystic lesion in each lung. N Engl J Med 1999;341:974–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aktan AO, Yalin R, Yegen C, et al. Surgical treatment of hepatic hydatid cysts. Acta Chir Belg 1993;93:151–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kornaros SE, Aboul-Nour TA. Frank intrabiliary rupture of hydatid hepatic cyst: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Coll Surg 1996;183:466–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paksoy M, Karahasanoglu T, Carkman S, et al. Rupture of the hydatid disease of the liver into the biliary tracts. Dig Surg 1998;15:25–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ulualp KM, Aydemir I, Senturk H, et al. Management of intrabiliary rupture of hydatid cyst of the liver. World J Surg 1995;19:720–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saremi F, McNamara TO. Hydatid cysts of the liver: long-term results of percutaneous treatment using a cutting instrument. AJR 1995; 165:1163–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Men S, Hekimoglu B, Yucesoy C, et al. Percutaneous treatment of hepatic hydatid cysts: an alternative to surgery. AJR 1999; 172:83–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Aretxabala X, Perez OL. The use of endoprostheses in biliary fistula of hydatid cyst. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;49:797–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dumas R, Le Gall P, Hastier P, et al. The role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the management of hepatic hydatid disease. Endoscopy 1999;31:242–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]