Abstract

Background: Multiple cancers may occur in an individual because of a genetic predisposition, environmental exposure, cancer therapy, or immunological deficiency. Colorectal cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers, and inherited factors play an important role in its aetiology.

Aims: To characterise the occurrence of multiple primary cancers in patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer and explore the possibility of a common aetiology for different cancer sites.

Patients: The Thames Cancer Registry database was used to identify patients with a first colorectal cancer, resident in the North or South Thames region, diagnosed between 1 January 1961 and 31 December 1995. A total of 127 281 patients were included, 61 433 men and 65 848 women.

Methods: Observed numbers of cancers occurring after the diagnosis of colorectal cancer were compared with expected numbers, calculated using appropriate age, sex, and period specific rates, to obtain standardised incidence ratios. The occurrence of colorectal cancers subsequent to cancers at other sites was also examined.

Results: Small intestinal cancer was significantly increased in men diagnosed with colorectal cancer before the age of 60 years and in women diagnosed with colorectal cancer after the age of 65 years. Colorectal cancer was also significantly increased after a first diagnosis of cancer of the small intestine. Other cancer sites with a significant increase after colorectal cancer included the cervix uteri, corpus uteri, and ovary.

Conclusions: Patients with colorectal cancer are at increased risk of developing cancer at a number of other sites. Some of these associations are consistent with the effects of known inherited cancer susceptibility genes.

Keywords: primary cancers, colorectal cancer, cancer genetics

An individual may develop multiple primary cancers for several reasons: environmental exposure to carcinogens, genetic predisposition, therapy for the first cancer, or immunological deficiency.

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers diagnosed throughout the world, in both men and women, and inherited factors are known to play a major role in its aetiology. Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome is an autosomal dominantly inherited condition caused by mutations in several “mismatch repair” genes, the most common being hMSH2 and hMLH1.1 The primary risk is to cancer of the colon and rectum but family studies have shown that mutation carriers also have increased relative risks of developing cancers of the corpus uteri, ovary, stomach, pancreas, and small intestine.2, 3 The cumulative lifetime risks among putative HNPCC carriers have been reported as 78% for colorectal cancer, 43% for cancer of the corpus uteri, 19% for stomach cancer, 18% for biliary tract cancer, 10% for urinary tract cancer, and 9% for ovarian cancer.4 Another condition, familial adenomatous polyposis, carries a very high risk of colorectal adenomas and cancers, and an increased relative risk of small intestinal and thyroid cancer.5, 6 Hereditary cancers characteristically have an onset at a younger age than sporadic cancer.7

A number of population based studies focusing on second primary cancers occurring after cancers of the colon and rectum have been reported.8–14 The results of these studies are varied and include significantly increased risks of second cancers of the stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum, kidney, bladder, prostate, thyroid, breast, corpus uteri, ovary, brain, and gall bladder. Cancer registries throughout the world differ with regard to reporting, follow up, and coding practices which may account for some of the variation in results. Also, different criteria for inclusion may be used. For example, some multiple primary studies exclude cancers that are diagnosed within one year of the index cancer whereas others exclude cancers diagnosed within two months.

In this paper, we have used one of the world's largest population based cancer registries to identify second cancers which occur at a higher than expected rate after the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. The sequence of cancers occurring in individual patients with multiple cancers, which included colorectal cancer, was examined to establish pairs of cancer sites with mutually increased risks. Cases of second cancer induced by treatment are clearly sequence specific (that is, treatment induced cancers occur second). Cancers induced by chemotherapy and radiotherapy are also likely to occur in a predictable time window after treatment for the first cancer—the time being 1–5 years for acute myeloid leukaemia and 10–25 years for solid tumours.

METHODS

The Thames Cancer Registry (TCR) is a population based registry that started in 1960 and now covers a population of 14 million in southeast England. The database currently contains details of over 1.5 million incident cancers. Patients registered at the TCR represent a cohort of individuals followed up from diagnosis to death. The numbers of observed second primary cancers diagnosed after an initial cancer can be compared with those expected using age and sex specific cancer rates observed in the corresponding region during the same time period.

Approximately 5% of patients registered at the TCR are diagnosed with multiple primary cancers (excluding basal cell carcinomas of the skin). An important consideration is that metastases or recurrences of the initial tumour should not be classified as new primary tumours. As a general rule, to be classified as a new primary cancer the tumour should be at a different anatomical site and of a different histological type from the first tumour, or to be stated explicitly as being a new primary tumour by the treating clinician.

An index cohort was created by extracting all registrations of patients with a first colorectal cancer (ICD-10 C18-C21), resident in the North or South Thames region, diagnosed between 1 January 1961 and 31 December 1995 from the TCR database. Cases were stratified by age at diagnosis of colorectal cancer (under 60 years or 60 years and over for men, under 65 years or 65 years and over for women) and each group was analysed separately. These cut off ages were chosen to include approximately one quarter of the total cases, for each sex, in the younger group for analysis. Within each individual, subsequent cancers were counted and sequenced according to the date of diagnosis. For patients with two or more subsequent cancers, each cancer was analysed as an independent observation.

Non-melanoma skin cancers and non-malignant tumours were excluded. Patients without a date of birth and those with a cancer at a different site, diagnosed on the same day as colorectal cancer, were not included.

Person years at risk were calculated from the date of diagnosis of colorectal cancer to the date of first diagnosis of cancer at a specified site or to the exit date (date of death, loss to follow up, or 85th birthday, whichever was earlier). Patients diagnosed prior to 1 January 1971 were followed up actively, obtaining death information, until 31 December 1982. These patients were censored at this date. Patients diagnosed after 31 December 1970 were followed up passively through the NHS Central Registry, which provides notifications of all deaths routinely to the registry. These patients were censored at 31 December 1996. Age/sex/period specific cancer incidence rates for the region covered by the TCR were then applied to the cohort to calculate the number of subsequent tumours that would be expected for each site. The observed number was divided by the expected number to obtain a standardised incidence ratio (SIR) estimate, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution. SIR estimates for intervals of 0–4 years, 5–9 years, 10–14 years, and 15 or more years after the colorectal cancer diagnosis were also calculated. All statistical analysis was performed using Stata.15 A total of 40 subsequent cancer sites were studied, classified according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD).16

This method was then repeated, using other cancer sites commonly observed to occur after colorectal cancer as the index site, to establish whether any of the same associations were seen with a subsequent colorectal cancer.

RESULTS

After exclusions, a total of 127 281 patients were reported to have a first primary colorectal cancer diagnosed between 1961 and 1995: 61 433 (48.3%) men and 65 848 (51.7%) women. Mean follow up time was 4.6 years for the younger men (under 60 years), 2.5 years for the older men, 5.0 years for the younger women (under 65 years), and 2.4 years for the older women. Results for individual secondary cancer sites are presented in tables 1 and 2 ▶ ▶. Sites for which five or fewer cases were observed in both men and women were omitted from the tables.

Table 1.

Standardised incidence ratios (SIR) for subsequent cancers after diagnosis of colorectal cancer in men, by age at diagnosis of colorectal cancer

| Colorectal cancer diagnosed at age <60 years | Colorectal cancer diagnosed at age 60+ years | |||||||

| Site | n | SIR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | n | SIR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

| Tongue | 3 | 1.43 | 0.30 | 4.17 | 6 | 0.74 | 0.27 | 1.61 |

| Mouth | 4 | 1.64 | 0.45 | 4.27 | 6 | 0.66 | 0.24 | 1.45 |

| Oropharynx | 2 | 1.40 | 0.17 | 5.16 | 5 | 1.06 | 0.35 | 2.48 |

| Oesophagus | 10 | 0.80 | 0.39 | 1.48 | 57 | 0.81 | 0.62 | 1.05 |

| Stomach | 30 | 1.07 | 0.72 | 1.52 | 139 | 0.75** | 0.63 | 0.88 |

| Small intestine | 3 | 3.45 | 0.71 | 10.1 | 6 | 1.49 | 0.55 | 3.24 |

| Colon | 69 | 2.33** | 1.81 | 2.95 | 113 | 0.58** | 0.47 | 0.69 |

| Rectum | 34 | 1.46* | 1.01 | 2.04 | 49 | 0.36** | 0.26 | 0.47 |

| Liver | 5 | 1.35 | 0.44 | 3.15 | 10 | 0.57 | 0.27 | 1.05 |

| Gall bladder | 2 | 0.96 | 0.12 | 3.46 | 9 | 0.73 | 0.33 | 1.39 |

| Pancreas | 16 | 1.07 | 0.61 | 1.74 | 62 | 0.71** | 0.54 | 0.91 |

| Larynx | 8 | 0.94 | 0.41 | 1.85 | 25 | 0.72 | 0.47 | 1.07 |

| Bronchus | 115 | 0.89 | 0.73 | 1.07 | 498 | 0.67** | 0.61 | 0.73 |

| Connective tissue | 3 | 1.79 | 0.37 | 5.22 | 5 | 0.77 | 0.25 | 1.80 |

| Skin melanoma | 2 | 0.39 | 0.05 | 1.42 | 14 | 0.90 | 0.49 | 1.51 |

| Prostate | 52 | 1.13 | 0.84 | 1.48 | 449 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 1.08 |

| Testis | 3 | 1.63 | 0.34 | 4.76 | 5 | 2.54 | 0.82 | 5.92 |

| Bladder | 33 | 0.95 | 0.66 | 1.34 | 213 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 1.10 |

| Kidney | 15 | 1.30 | 0.73 | 2.15 | 52 | 1.04 | 0.78 | 1.37 |

| Eye | 5 | 4.03* | 1.31 | 9.41 | 3 | 0.72 | 0.15 | 2.11 |

| Brain, nervous system | 8 | 0.85 | 0.37 | 1.68 | 11 | 0.50* | 0.25 | 0.90 |

| Thyroid | 0 | 1 | 0.26 | 0.01 | 1.43 | |||

| NHL | 15 | 1.09 | 0.61 | 1.81 | 54 | 0.94 | 0.70 | 1.22 |

| Multiple myeloma | 1 | 0.16* | 0.01 | 0.90 | 26 | 0.76 | 0.50 | 1.12 |

| Lymphoid leukaemia | 4 | 0.81 | 0.22 | 2.09 | 25 | 0.84 | 0.54 | 1.24 |

| Myeloid leukaemia | 4 | 0.84 | 0.23 | 2.14 | 23 | 0.80 | 0.51 | 1.20 |

| Other leukaemia | 2 | 2.70 | 0.33 | 9.76 | 5 | 0.93 | 0.30 | 2.18 |

| Total | 451 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 1.20 | 1892 | 0.76** | 0.73 | 0.80 |

| Total excl colorectal | 348 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 1.08 | 1730 | 0.80** | 0.77 | 0.84 |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Table 2.

Standardised incidence ratios (SIR) for subsequent cancers after diagnosis of colorectal cancer in women, by age at diagnosis of colorectal cancer

| Colorectal cancer diagnosed at age <60 years | Colorectal cancer diagnosed at age 60+ years | |||||||

| Site | n | SIR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | n | SIR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

| Tongue | 2 | 0.94 | 0.12 | 3.41 | 6 | 1.43 | 0.52 | 3.10 |

| Mouth | 1 | 0.41 | 0.01 | 2.28 | 2 | 0.42 | 0.05 | 1.50 |

| Oropharynx | 1 | 1.01 | 0.03 | 5.63 | 0 | |||

| Oesophagus | 12 | 0.94 | 0.49 | 1.65 | 30 | 0.81 | 0.55 | 1.16 |

| Stomach | 19 | 0.76 | 0.45 | 1.18 | 46 | 0.55** | 0.40 | 0.73 |

| Small intestine | 3 | 2.33 | 0.48 | 6.80 | 8 | 2.86* | 1.23 | 5.63 |

| Colon | 78 | 1.28* | 1.02 | 1.60 | 99 | 0.60** | 0.49 | 0.73 |

| Rectum | 33 | 1.04 | 0.72 | 1.47 | 38 | 0.49** | 0.35 | 0.67 |

| Liver | 2 | 0.64 | 0.08 | 2.32 | 4 | 0.56 | 0.15 | 1.42 |

| Gall bladder | 2 | 0.41 | 0.05 | 1.50 | 5 | 0.38* | 0.12 | 0.89 |

| Pancreas | 15 | 0.66 | 0.37 | 1.09 | 34 | 0.54** | 0.38 | 0.76 |

| Larynx | 3 | 1.06 | 0.22 | 3.09 | 1 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 1.29 |

| Bronchus | 106 | 1.14 | 0.93 | 1.37 | 182 | 1.00 | 0.86 | 1.16 |

| Connective tissue | 5 | 2.27 | 0.74 | 5.30 | 5 | 1.23 | 0.40 | 2.87 |

| Skin melanoma | 14 | 1.19 | 0.65 | 2.00 | 14 | 0.89 | 0.49 | 1.50 |

| Breast | 229 | 1.10 | 0.96 | 1.26 | 284 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 1.08 |

| Cervix uteri | 35 | 1.61* | 1.12 | 2.24 | 34 | 1.42 | 0.99 | 1.99 |

| Corpus uteri | 57 | 1.56** | 1.18 | 2.02 | 49 | 0.98 | 0.72 | 1.29 |

| Ovary | 110 | 2.56** | 2.11 | 3.09 | 97 | 1.59** | 1.29 | 1.94 |

| Other female genital | 11 | 1.65 | 0.82 | 2.96 | 20 | 1.12 | 0.68 | 1.72 |

| Bladder | 19 | 0.91 | 0.55 | 1.42 | 54 | 0.98 | 0.73 | 1.27 |

| Kidney | 11 | 1.10 | 0.55 | 1.97 | 25 | 1.29 | 0.84 | 1.90 |

| Eye | 4 | 2.19 | 0.60 | 5.60 | 3 | 1.19 | 0.25 | 3.46 |

| Brain, nervous system | 6 | 0.55 | 0.20 | 1.19 | 7 | 0.61 | 0.25 | 1.26 |

| Thyroid | 8 | 2.24 | 0.97 | 4.42 | 10 | 1.56 | 0.75 | 2.86 |

| NHL | 15 | 0.76 | 0.43 | 1.26 | 28 | 0.71 | 0.47 | 1.03 |

| Multiple myeloma | 7 | 0.73 | 0.29 | 1.50 | 14 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 1.04 |

| Lymphoid leukaemia | 3 | 0.52 | 0.11 | 1.53 | 16 | 1.01 | 0.58 | 1.64 |

| Myeloid leukaemia | 6 | 0.87 | 0.32 | 1.90 | 19 | 1.15 | 0.69 | 1.80 |

| Other leukaemia | 0 | 4 | 1.20 | 0.33 | 3.07 | |||

| Total | 827 | 1.19** | 1.11 | 1.28 | 1147 | 0.87** | 0.82 | 0.92 |

| Total excl colorectal | 716 | 1.19** | 1.11 | 1.28 | 1010 | 0.93* | 0.88 | 0.99 |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Digestive cancers

Cancers of the colon and rectum were significantly increased in men diagnosed with a first colorectal cancer before the age of 60 years, with SIR values of 2.33 and 1.46, respectively. The overall SIR for a subsequent colorectal cancer was 1.95 (95% CI 1.60–2.36). The increase in colon cancers was seen throughout the follow up period but the increase in rectal cancers was restricted to the first five years after the diagnosis of the first colorectal cancer (fig 1 ▶). In the older cohort of men, four sites had significantly fewer cancers than expected: stomach (SIR 0.75), colon (SIR 0.58), rectum (SIR 0.36), and pancreas (SIR 0.71). The overall SIR for a subsequent colorectal cancer was 0.48 (95% CI 0.42–0.57).

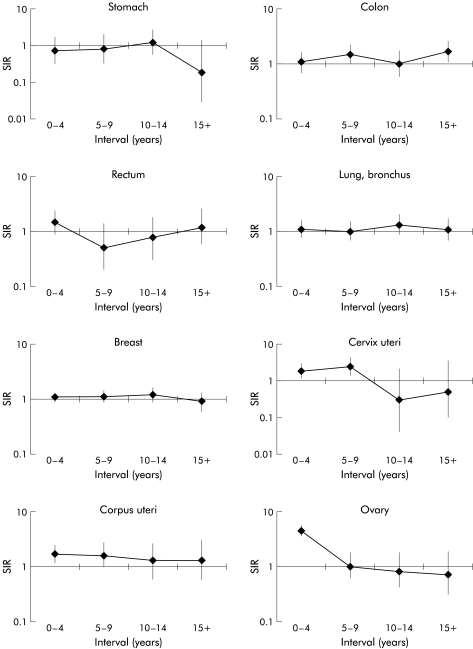

Figure 1.

Standardised incidence ratio (SIR) for cancers after colorectal cancer, diagnosed in men before the age of 60 years, by interval since diagnosis.

Women diagnosed with a first colorectal cancer before the age of 65 years had a significantly increased risk of developing a subsequent colon cancer (SIR 1.28). This increase was fairly consistent throughout the follow up period (fig 2 ▶). The SIR for colorectal cancer was 1.20 (95% CI 1.00–1.45). Small intestinal cancer was significantly increased in the older cohort of women (SIR 2.86) whereas significantly reduced risks were seen for cancers at four sites in this group of women: stomach (SIR 0.55), colon (SIR 0.60), rectum (SIR 0.49), and pancreas (SIR 0.54). The overall SIR for colorectal cancer was 0.56 (95% CI 0.48–0.67).

Figure 2.

Standardised incidence ratio (SIR) for cancers after colorectal cancer, diagnosed in women before the age of 65 years, by interval since diagnosis.

Female reproductive cancers

Women diagnosed with colorectal cancer before the age of 65 years showed significant increases in cancer of the cervix uteri (SIR 1.61), corpus uteri (SIR 1.56), and ovary (SIR 2.56). The increase in ovarian cancer was limited to the first five years after the first colorectal cancer diagnosis, the increase in cervix uteri was seen in the first 10 years, and the increase in cancer of the corpus uteri was consistent throughout the follow up period. A significant increase was also seen in the older cohort for cancer of the ovary (SIR 1.59).

Other cancers

Cancer of the eye was significantly increased in men with a first colorectal cancer diagnosed before the age of 60 years (SIR 4.03). It should be noted that none of these five cases were retinoblastomas. Lung cancer and brain cancer were significantly decreased in older men, the SIRs being 0.67 and 0.50, respectively. Multiple myeloma was significantly decreased in younger men (SIR 0.16).

Colorectal cancer as a subsequent cancer

Colorectal cancer was significantly increased after a first diagnosis of small intestinal cancer in both men and women, with SIRs of 3.61 and 3.06, respectively (table 3 ▶). Colorectal cancer was also increased after a first diagnosis of cancer of the ovary (SIR 1.93), corpus uteri (SIR 1.18), and cervix uteri (SIR 1.19).

Table 3.

Standardised incidence ratios (SIR) for occurrence of colorectal cancer after a first cancer at selected sites, diagnosed between 1961 and 1995

| Men | Women | |||

| First cancer site | n | SIR (95% CI) | n | SIR (95% CI) |

| Small intestine | 14 | 3.61 (1.97, 6.05) | 10 | 3.06 (1.47, 5.62) |

| Colorectal | 265 | 0.69 (0.61, 0.77) | 151 | 0.84 (0.71, 0.98) |

| Testis | 23 | 1.25 (0.79, 1.88) | — | — |

| Cervix uteri | — | — | 127 | 1.19 (1.00, 1.42) |

| Corpus uteri | — | — | 250 | 1.18 (1.04, 1.33) |

| Ovary | — | — | 165 | 1.93 (1.65, 2.25) |

| Eye | 10 | 0.72 (0.35, 1.33) | 3 | 0.28 (0.06, 0.82) |

DISCUSSION

Overall risks

The overall risk of subsequent cancer in men diagnosed with colorectal cancer before the age of 60 was increased but this increase was not significant at the 95% level. The risk in men diagnosed at age 60 years and above was significantly lower than expected. The overall risk in women diagnosed with colorectal cancer before the age of 65 years was increased significantly by about 20%. Women diagnosed at an older age had a significantly lower than expected risk of developing a subsequent cancer.

It is likely that the decreased risks found in this study, especially in older individuals, were largely due to under ascertainment. The TCR may not always be notified of subsequent cancers diagnosed in patients who have moved out of the area. Multiple tumours may not be matched up correctly to the same person, which would lead to an artificially long follow up and the creation of “immortals” on the database. Finally, a new primary cancer may be misdiagnosed as a recurrence or metastasis.

Digestive cancers

Small intestinal cancer was increased in all groups but the increase was only significant in older women. Colorectal cancer was significantly increased after small intestinal cancer for both men and women. This association could be due to individuals with HNPCC as studies have shown that there is a highly increased relative risk of small intestinal cancer in families with HNPCC.17 A Dutch study reported relative risks of 292 and 103 in carriers of hMLH1 and hMSH2 mutations, respectively.3 It is difficult to assess the true incidence of subsequent colon and rectal cancer because treatment for the first tumour may involve surgical removal of all or part of the organ. This would result in the SIR being underestimated as these patients will be at lower risk of developing colorectal cancers than the general population. Colon cancer was significantly increased in both men and women diagnosed with the first cancer at a young age but it was significantly decreased for those patients diagnosed with the first cancer at an older age. Rectal cancer was only significantly increased in men diagnosed before the age of 60 years. The fact that we did not find a significant increase in stomach cancer was surprising as it is known to be associated with HNPCC17, 18 but other cancer registry studies have also failed to report an increased risk of stomach cancer after colorectal cancers.9, 11–13 In fact, a significantly decreased risk of stomach cancer after rectal cancer has been found in Connecticut, Denmark, Finland, and Italy.8, 9, 12, 13 Reasons for these deficits are not clear. A low socioeconomic status is associated with a higher risk of stomach cancer whereas the converse is true for colon cancer19, 20 but other factors such as the protective effect of fruit and vegetables are common to both sites. An Italian population based study reported a non-significant deficit of stomach cancer in HNPCC family members but this was thought to be due to insufficient length of follow up.21 Another HNPCC family study in the Netherlands found that almost all of the cases of stomach cancer occurred in the previous generation of family members presenting with colorectal cancer, rather than in the same individuals.22

Female reproductive cancers

There were significant increases in cancers of the cervix uteri, corpus uteri, and ovary. Colorectal cancers were also significantly increased after a first cancer at each of these sites. Cancers of the corpus uteri and ovary are both increased in individuals with HNPCC.17 Hormonal factors may explain some of the association between colorectal and corpus uteri cancers. Nulliparity is associated with a two to threefold increase in cancer of the corpus uteri.23 An American case control study reported that nulliparous women with a positive family history of colorectal cancer had a relative risk of 2.38 for colorectal cancer compared with 1.21 for women with higher parity (>4).24 The possibility of metastatic spread to the ovaries has also to be considered, particularly as the increase in ovarian cancer was confined to the first five years after diagnosis. However, first degree relatives of patients with HNPCC in the UK have been shown to have a significantly increased risk of dying from ovarian cancer (relative risk 3.18).25 The observed increase in cancer of the cervix uteri is surprising, particularly as this cancer is more common in lower socioeconomic groups, in contrast with colon cancer.26 The significant increase is restricted to the first 10 years after diagnosis of colorectal cancer, which suggests that treatment for the first cancer, increased surveillance, and misdiagnosed recurrences may be contributing factors. The cohort of patients with colorectal cancer includes 2678 (2%) anal cancers. If women with a first anal cancer are excluded from the cohort, the increase in cervical cancer is attenuated and it no longer reaches statistical significance (SIR 1.43, 95% CI 0.96–2.04 in the younger group and SIR 1.37, 95% CI 0.94–1.94 in the older group). This suggests that some of the increase may be due to human papillomavirus which is known to be associated with both anal cancer and cervical cancer.27

The role of HNPCC

As HNPCC is known to cause an increased risk of cancers of the corpus uteri, ovary, small intestine, stomach, bladder, and kidney, it is a strong candidate for the genetic condition underlying co-occurrence of colorectal cancer with these other cancer types. Penetrances for these cancers in HNPCC have been estimated in Finnish HNPCC families.4 If we assume that the increased relative risks found in our population were solely due to HNPCC, we can estimate the proportion of colorectal cancer cases in our study that would have HNPCC (table 4 ▶). In all cases except for ovarian cancer, this estimated proportion lies within the range 0.2–2.0%, which is consistent with published estimates of the population prevalence of the condition in colorectal cancer cases.28–30 However, in the case of ovarian cancer, the estimated proportion of HNPCC cases required to produce the observed SIR value far exceeds this, suggesting that additional factors such as metastasis or other genes predisposing to both ovarian and colorectal cancer are involved.

Table 4.

Estimated percentage of young onset colorectal cancer (CRC) cases due to HNPCC in the study population

| Cancer site | SIR in study population | Penetrance in HNPCC4 (%) | Lifetime risk in general population32 (%) | RR in HNPCC | Estimate of % of young onset CRC cases due to HNPCC in study |

| Corpus uteri | 1.56 | 43 | 1.0 | 43 | 1.3 |

| Ovary | 2.56 | 9 | 1.32 | 6.82 | 26.8 |

| Stomach (men) | 1.07 | 19 | 1.27 | 15 | 0.5 |

| Stomach (women) | 0.76 | 19 | 0.38 | 50 | — |

| Bladder (men) | 0.95 | 10 | 1.47 | 6.8 | — |

| Bladder (women) | 0.91 | 10 | 0.42 | 23.8 | — |

| Kidney (men) | 1.30 | 18 | 0.72 | 25 | 1.25 |

| Kidney (women) | 1.10 | 18 | 0.33 | 54.5 | 1.89 |

HNPCC, hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer; SIR, standardised incidence ratio; RR, relative risk.

Other cancers

Cancers of the eye were significantly increased in men diagnosed with colorectal cancer before the age of 60 years. Six of the eight eye cancers were diagnosed as malignant melanomas. The Denmark and Connecticut cancer registry studies also reported increases in ocular cancer but they were not statistically significant. An American study showed that the overall cancer prevalence was higher than expected in patients with uveal melanoma, with the majority of other cancers being diagnosed before the diagnosis of uveal melanoma.31 An increase in colon cancer was reported but was not significant.

In conclusion, we have detected a number of associations between extracolonic cancers and colorectal cancer, especially in individuals diagnosed at a young age. Inherited susceptibility genes (particularly those causing HNPCC) which confer increased risks for both cancer types could account for most of these associations.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support of the Dunhill Medical Trust who funded this study.

Abbreviations

TCR, Thames Cancer Registry

HNPCC, hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer

ICD, International Classification of Diseases

SIR, standardised incidence ratio

REFERENCES

- 1.Lynch HT, Smyrk T. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome). An updated review. Cancer 1996;76:1149–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mecklin P, Jarvinen HJ. Tumor spectrum in cancer family syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer). Cancer 1991;68:1109–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasen HFA, Wijnen JT, Menko FH, et al. Cancer risk in families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer diagnosed by mutation analysis. Gastroenterology 1996;110:1020–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aarnio M, Mecklin J-P, Aaltonen LA, et al. Life-time risk of different cancers in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome. Int J Cancer 1995;64:430–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giardiello FM, Offerhaus GJA, Lee DH, et al. Increased risk of thyroid and pancreatic carcinoma in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut 1993;34:1394–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giardiello FM, Offerhaus JGA. Phenotype and cancer risk of various polyposis syndromes. Eur J Cancer 1995;31:1085–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strong LC, Amos CI. Inherited susceptibility. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF, eds. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996:559–83.

- 8.Hoar SK, Wilson J, Blot WJ, et al. Second cancer following cancer of the digestive system in Connecticut, 1935–82. In: Greenwald P, ed. Multiple cancers in Connecticut and Denmark, National Cancer Institute Monograph 68. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1985;49–82. [PubMed]

- 9.Lynge E, Jensen OM, Carstensen B. Second cancer following cancer of the digestive system in Denmark, 1943–80. In: Greenwald P, ed. Multiple cancers in Connecticut and Denmark, National Cancer Institute Monograph 68. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1985;277–308. [PubMed]

- 10.Enblad P, Adami HA, Glimelius B, et al. The risk of subsequent primary malignant diseases after cancers of the colon and rectum. Cancer 1990;65:2091–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levi F, Randimbison L, Te VC, et al. Multiple primary cancers in the Vaud Cancer Registry, Switzerland, 1974–89. Br J Cancer 1993;67:391–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teppo L, Pukkala E, Saxen E. Multiple cancer—an epidemiologic exercise in Finland. J Natl Cancer Inst 1985;75:207–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buiatti E, Crocetti E, Acciai S, et al. Incidence of second primary cancers in three Italian population-based cancer registries. Eur J Cancer 1997;33:1829–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slattery ML, Mori M, Gao R, et al. Impact of family history of colon cancer on development of multiple primaries after diagnosis of colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 1995;38:1053–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 6.0. College Station: Stata Corporation, 1999.

- 16.World Health Organisation. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision. Geneva: WHO, 1992. [PubMed]

- 17.Watson P, Lynch HT. Extracolonic cancer in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cancer 1993;71:677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch HT, Smyrk TC, Watson P, et al. Genetics, natural history, tumor spectrum, and pathology of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: an updated review. Gastroenterology 1993;104:1535–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nomura A. Stomach cancer. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF, ed. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996;707–24.

- 20.Schottenfeld D, Winawer SJ. Cancers of the large intestine. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF, ed. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996:813–40.

- 21.Ponz de Leon M, Benatti P, Pedroni M, et al. Risk of cancer revealed by follow-up of families with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer: a population-based study. Int J Cancer 1993;55:202–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasen HFA, Offerhaus GJA, den Hartog Jager FCA, et al. The tumour spectrum in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer: a study of 24 kindreds in the Netherlands. Int J Cancer 1990;46:31–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grady D, Ernster VL. Endometrial cancer. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF, ed. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996:1058–89.

- 24.Newcomb PA, Taylor JO, Trentham-Dietz A. Interactions of familial and hormonal risk factors for large bowel cancer in women. Int J Epidemiol 1999;28:603–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itoh H, Houlston RS, Harocopos C, et al. Risk of cancer death in first-degree relatives of patients with hereditary non-polyposis cancer syndrome (Lynch type II): a study of 130 kindreds in the United Kingdom. Br J Surg 1990;77:1367–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thames Cancer Registry. Cancer in South East England 1997. Cancer incidence, prevalence, survival and treatment for residents of the Health Authorities in South East England. UK: Thames Cancer Registry, 2000;92–9.

- 27.Mueller NE, Evans AS, London WT. Viruses. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF, ed. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996; 502–31.

- 28.Peel DJ, Ziogas A, Fox EA, et al. Characterization of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer families from a population-based series of cases. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1517–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Modica S, Roncucci L, Benatti P, et al. Familial aggregation of tumors and detection of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer in 3-year experience of 2 population-based colorectal-cancer registries. Int J Cancer 1995;62:685–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cole TRP, Sleightholme HV. ABC of colorectal cancer. The role of clinical genetics in management. BMJ 2000;321:943–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turner BJ, Siatkowski RM, Augsberger JJ, et al. Other cancers in uveal melanoma patients and their families. Am J Opthalmol 1989;107:601–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thames Cancer Registry. Cancer in South East England 1996. UK: Thames Cancer Registry, 1997.