Abstract

Background and aims: Up to 60% of patients treated with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) require angioplasty or restenting during the first year of follow up because of TIPS dysfunction (stenosis of the intrahepatic shunt increasing the portal pressure gradient above the 12 mm Hg threshold). We hypothesised that in patients with TIPS stenosis, propranolol administration, by decreasing portal inflow, would markedly decrease portal pressure.

Patients and methods: Eighteen patients with TIPS dysfunction were investigated by measuring portal pressure gradient before and after acute propranolol administration (0.2 mg/kg intravenously; n=18).

Results: Propranolol markedly reduced the portal pressure gradient (from 16.6 (3.5) to 11.9 (4.8) mm Hg; p<0.0001), cardiac index (−26 (7)%), and heart rate (−18 (7)%) (p<0.0001). Portal pressure gradient decreased to less than 12 mm Hg in nine patients, more frequently in those with moderate dysfunction (portal pressure gradient 16 mm Hg) than in patients with severe dysfunction (portal pressure gradient >16 mm Hg) (8/10 v 1/8; p=0.015).

Conclusions: Propranolol therapy may delay the increase in portal pressure and reduce the need for reintervention in patients with TIPS dysfunction.

Keywords: portal hypertension, liver cirrhosis, variceal bleeding, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is being widely used for the treatment of the complications of portal hypertension.1–4 TIPS markedly reduces the portal pressure gradient (PPG) and is very effective in decreasing the risk of recurrent complications from portal hypertension.1–5 Recent studies have shown that to offer adequate protection, TIPS should reduce and maintain PPG below 12 mm Hg.5 However, PPG tends to increase during follow up owing to the development of stenosis or occlusion of the shunt.3,5–7 This process is known as TIPS dysfunction, and is due to hyperplasia and fibrosis of the neointimal that covers the stent shunt.5,8 TIPS dysfunction promotes the reappearance of portal hypertension and therefore the risk of recurrence of the complications of portal hypertension. Unfortunately, TIPS dysfunction occurs very frequently. Up to 60% of patients treated with TIPS will require angioplasty or restenting during the first year of follow up because of TIPS dysfunction.1–9

We hypothesised that in the setting of a stenosed TIPS, reducing splanchnic blood flow by means of propranolol administration should result in a marked fall in portal pressure and delay the increase in PPG above the threshold values for clinical complications.

Our study was designed to test this hypothesis by examining the effects of acute and long term propranolol administration on PPG and splanchnic and systemic haemodynamics in a series of patients with TIPS dysfunction.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study included 18 consecutive patients with cirrhosis that had a TIPS procedure because of variceal bleeding and who on follow up were found to have TIPS dysfunction. In six cases (three with oesophageal and three with gastric varices) TIPS was performed as a salvage procedure after lack of control by endoscopic and pharmacological means. In 12 cases (all with bleeding oesophageal varices) TIPS was performed as an elective procedure. TIPS dysfunction was demonstrated by the finding of a PPG >12 mm Hg at direct TIPS catheterisation.5 TIPS dysfunction was considered to be moderate when the PPG was 12–16 mm Hg and severe when the PPG was >16 mm Hg. Clinical data on the patients studied are summarised in table 1 ▶

Table 1.

Clinical data of patients with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt dysfunction included in the study

| Age (y) | 53 (11) |

| Aetiology of cirrhosis (alcoholic/non-alcoholic) | 9/9 |

| Child-Pugh score (points) | 7.5 (1.6) |

| Child-Pugh class (A/B/C) | 5/11/2 |

| Ascites (yes/no) | 6/12 |

| Diuretic treatment (yes/no) | 6/12 |

| Platelet count (106/ml) | 107 (65) |

| Haematocrit | 0.32 (0.06) |

| Prothrombin ratio (%) | 60 (13) |

| Oesophageal varices (small/big, %) (n=15) | 33/77 |

The study was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee for Clinical Research of the Hospital Clinic. The nature of the study was explained to the patients, and written informed consent was obtained in every case.

After an overnight fast, patients were transferred to the hepatic haemodynamic laboratory. Under local anaesthesia, a venous introducer was placed in the right jugular vein using the Seldinger technique. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a 7F catheter was advanced into the portal vein through the TIPS for pressure measurements and angiography. PPG was calculated as the difference between portal venous pressure and inferior vena cava pressure. If angiography confirmed TIPS stenosis and PPG was >12 mm Hg, the patient was eligible for the study. In addition, a Swan-Ganz catheter (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, Illinois, USA) was advanced into the pulmonary artery for measurement of cardiopulmonary pressures and cardiac output (thermal dilution). A solution of indocyanine green (ICG; Pulsion Medical Systems, Munich, Germany) containing 2% serum albumin was infused intravenously at a constant rate of 0.2 mg/min. After an equilibration period of at least 40 minutes, a 7F catheter was advanced into an hepatic vein, different from the one that had the TIPS, and four separate sets of simultaneous samples of peripheral and hepatic venous blood were obtained for measurement of hepatic blood flow (HBF), as previously described.10 Shunt blood flow is not included in this calculation of HBF. All measurements were performed in triplicate, and permanent tracings were obtained on a multichannel recorder. Pressures are reported in mm Hg and cardiac output as cardiac index (CI) (litre×min/m2). Mean arterial pressure was measured non-invasively with an automatic sphygmomanometer (Mac-Lab, K74A0841J; Marquette, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA). Heart rate (HR) was derived from continuos electrocardiogram monitoring, and arterial oxygen saturation was monitored continuously by means of a pulse oximeter.

After completing baseline haemodynamic measurements, 18 patients received an intravenous propranolol infusion of 0.2 mg/kg in 10 minutes and all measurements were repeated 20 minutes later.11 After completing these measurements, all patients received balloon angioplasty.

Statistics

Results are reported as mean (SD). Statistical analysis of the results was performed using the unpaired and paired Student’s t test, ANOVA, and Fisher’s exact test, as needed. Significance was established at p<0.05. All calculations were performed using the SPSS 9.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

RESULTS

Clinical data of the patients are shown in table 1 ▶. The degree of TIPS dysfunction (baseline PPG) was similar in patients from Child-Pugh classes A, B, and C (16.8 (2.3), 16.8 (4.1), and 15.0 (2.8) mm Hg, respectively; NS)

Haemodynamic effects of acute propranolol administration

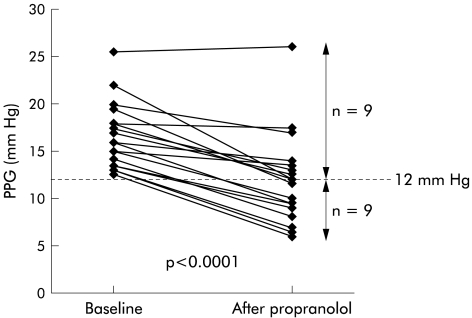

TIPS dysfunction was moderate in 10 patients and severe in eight. Acute propranolol administration caused a significant reduction in HR, CI, and HBF while mean arterial pressure was not modified (table 2 ▶). PPG decreased markedly (from 16.6 (3.5) to 11.9 (4.8) mm Hg, −30 (16)%; p<0.0001). Individual changes in PPG are shown in fig 1 ▶. As illustrated, PPG decreased below 12 mm Hg in nine of 18 patients (50%).

Table 2.

Haemodynamic effects of acute propranolol administration (n=18)

| Baseline | Post-propranolol | p Value | |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 82 (13) | 67 (10) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac index (l/min/m) | 5.5 (1.0) | 4.1 (0.8) | <0.0001 |

| MAP (mm Hg) | 82 (12) | 80 (13) | NS |

| RAP (mm Hg) | 6.6 (2.0) | 10.3 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| PPG (mm Hg) | 16.6 (3.5) | 11.9 (4.8) | <0.0001 |

| PP (mm Hg) | 25.6 (5.4) | 23.6 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| IVCP (mm Hg) | 8.9 (3.3) | 11.7 (2.5) | <0.0001 |

| HBF (l/min ) | 0.50 (0.20) | 0.44 (0.20) | <0.02 |

MAP, mean arterial pressure; RAP, right atrial pressure; PPG, portal pressure gradient; PP, portal pressure; IVCP, inferior vena cava pressure; HBF, hepatic blood flow.

All data are mean (SD).

Figure 1.

Individual values for portal pressure gradient (PPG) before and after acute administration of propranolol.

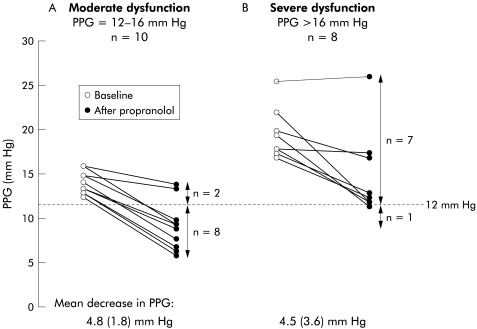

The proportion of patients with a decreasing PPG to <12 mm Hg was significantly greater among the 10 patients with moderate dysfunction than in the eight patients with severe TIPS dysfunction (80% v 13%; p=0.015) (fig 2 ▶). This was related to the lower baseline PPG of patients with moderate dysfunction (14.2 (1.3) mm Hg v 19.7 (2.9) mm Hg in severe dysfunction) as the mean fall in PPG was similar in both groups (4.8 (1.8) mm Hg or 35 (14)% in moderate dysfunction v 4.5 (3.6) mm Hg or 23 (17)% in severe dysfunction; NS). Patients with small varices (most with moderate dysfunction) had a greater fall in PPG than patients with big varices (−7.3 (3.1) mm Hg v −4.2 (2.2) mm Hg, respectively; p=0.08). There were no differences in the reduction in HBF, HR, or CI between patients with moderate or severe dysfunction (HBF −14 (15)% v −9 (14)%, NS; HR −16 (5) v −20 (8)%, NS; CI −25 (6) v −26 (9)%, NS).

Figure 2.

Individual values for portal pressure gradient (PPG) in patients with moderate and severe transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) dysfunction. The number of patients with a decreasing PPG to below 12 mm Hg was significantly greater among those with moderate dysfunction than in those with severe TIPS dysfunction (8/10 v 1/8; p=0.015). This was due to the lower baseline PPG of patients with moderate dysfunction as the absolute fall in PPG was similar in both groups.

The PPG response to propranolol was not different in patients with alcoholic compared with non-alcoholic cirrhosis (−24 (16)% v −34 (15)%, respectively; NS) and was not influenced by the degree of liver failure (−21 (12)% v −32 (18)% v −36 (14)% in Child-Pugh A, B, and C groups, respectively; NS).

Five of these patients with recurrent TIPS dysfunction despite repeated angioplasty (PPG 13.0 (2.6) mm Hg) were studied again after long term propranolol administration. After a mean of 3 (2) months, none had recurrent complications from portal hypertension, and PPG was below 12 mm Hg in four of these five patients (mean final PPG 10.5 (3.2) mm Hg; p<0.1 v baseline).

DISCUSSION

The portal pressure gradient is the result of the interaction of portal blood flow and the resistance that the portal hepatic vascular bed opposes to it. Increases in vascular resistance and blood flow will raise the PPG. Conversely, reduction in vascular resistance and/or blood flow will decrease the PPG. Therapy for portal hypertension is based on these concepts.12–14 Thus the use of beta adrenergic blockers, and vasopressin and somatostatin derivatives is based on the capacity of these agents to decrease portal blood inflow and thereby portal pressure.14 Surgical portosystemic shunts,15,16 and more recently TIPS,1–6 illustrate the alternative approach in which the PPG is decreased by reducing the increased resistance to portal blood flow by means of bypassing the increased hepatic vascular resistance caused by cirrhosis.

Small diameter “calibrated” shunts17 and TIPS2,4 were introduced with the hope that they would be large enough to achieve a reduction in portal pressure sufficient to prevent or correct the complications of portal hypertension while being small enough not to be associated with an excessive risk of encephalopathy and liver failure. Many subsequent studies have confirmed that TIPS is indeed highly effective in the treatment of portal hypertension.1,3,5,6 However, in contrast with surgical shunt, the reduction in PPG achieved by TIPS is not maintained over time, due to the very frequent development of TIPS dysfunction,5–7 which calls for repeated reintervention to maintain the PPG below the 12 mm Hg threshold value for the appearance of complications of portal hypertension.5,18,19 Indeed, a previous study from our laboratory showed that TIPS dysfunction—defined as an increase in PPG above 12 mm Hg—occurs in up to 80% of patients and that up to 70% required reintervention.5 The reported incidence of TIPS dysfunction varies among studies due to different definitions or cut off values, but in a recent meta-analysis of nine randomised controlled trials averaged 50% at one year.9 When TIPS dysfunction develops, the only successful treatment to date is reintervention, using balloon angioplasty and in some cases restenting. This is indeed a major caveat of TIPS.20–22

In this study, we examined if a simple inexpensive therapy, such as administration of propranolol, could diminish the haemodynamic consequences of TIPS dysfunction. Indeed, our results demonstrated that propranolol markedly reduced the PPG in patients with TIPS dysfunction. In fact, the decrease in PPG was so marked that 50% of patients reduced the PPG to below the 12 mm Hg threshold. This was specially evident in patients with moderate dysfunction in which 80% had such an optimal response, suggesting that propranolol therapy may be adequate to maintain the PPG in the safe range in a large proportion of patients with moderate TIPS dysfunction. Therefore, our findings suggest that propranolol administration may decrease the haemodynamic consequences of TIPS dysfunction and thus decrease the frequency by which these patients will require reintervention. Also, it can be proposed that adding propranolol therapy to all patients treated by TIPS may delay the reappearance of significant portal hypertension after TIPS. This concept is supported by the results obtained in our five patients with recurrent TIPS dysfunction that were treated with long term propranolol administration. Obviously, the real value of concomitant beta blocker therapy in this situation should be evaluated objectively in randomised controlled trials. The fact that reintervention is both costly, invasive, and demanding, and that propranolol is safe and inexpensive adds priority to such a study. Another situation where the current findings may have practical implications is for the occasional patient who fails to lower the PPG to below 12 mm Hg following TIPS.

The reduction in the PPG after propranolol observed in our patients with TIPS dysfunction exceeds markedly what is usually observed in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension not treated with TIPS. Many studies have shown that only about one third (or less) of these patients will exhibit a marked haemodynamic response, as defined by a fall in PPG to below 12 mm Hg or over 20% of baseline values.14,18,19,23,24 The very pronounced decrease in the PPG in patients with TIPS dysfunction may involve several mechanisms. The fall in CI and HR observed in our patients was similar to previous studies in patients without TIPS,18,19,23,24 so the degree of beta blockade is not an explanation. However, it is worth emphasising that the portal pressure response to propranolol is markedly influenced by the effects of beta blockade on portal collateral resistance.25 Collateral resistance is increased by beta blockers, which means that the fall in PPG is less marked than the decrease in portal collateral blood flow.25 In contrast, intrahepatic resistance is not markedly influenced by propranolol.26 This is thought to be the reason why cirrhotics with portal hypertension but without varices, with a limited extent of collateralisation, exhibit a more pronounced decrease in PPG than patients with varices.27 Patients with TIPS behave as cirrhotics with little amount of collaterals as TIPS markedly decreases the size of varices and the extent of extrahepatic portal systemic shunts5 that may constrict under beta blockers.25,28 Even in patients that have developed TIPS dysfunction, especially when this is moderate, it is likely that the extent of extrahepatic collaterals is still below what it was before TIPS.

On the other hand, TIPS is know to worsen the hyperkinetic circulation of cirrhosis29 which is likely to be due to enhanced release of nitric oxide induced by shear stress.30,31 This is another explanation for the favourable effects of propranolol in patients with TIPS as propranolol administration markedly attenuates the hyperkinetic syndrome.

Another issue to consider is whether propranolol therapy may influence the degree or likelihood of post-TIPS encephalopathy. Certainly, by decreasing splanchnic blood flow propranolol will decrease the absolute amount of shunt blood flow.24 However, it is likely that rather than absolute shunt flow, post-shunt encephalopathy is influenced by relative shunt flow—the fraction of portal blood flow not perfusing functional liver tissue—which is probably not increased by beta blockade. Although none of our patients included in the long term administration study had encephalopathy during the study period, this issue requires further study.

In summary, the present study demonstrated that in patients with TIPS dysfunction, propranolol administration markedly decreased the PPG to the point that a large proportion of patients achieved values well below the 12 mm Hg threshold for clinical complications. This was especially true among patients with moderate TIPS dysfunction. The results of this study suggest that concomitant propranolol therapy may decrease the need for reintervention in TIPS treated patients, and provides the rationale for testing this hypothesis in appropriate randomised clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS 2000-0444) and Plan Nacional de I+D (SAF99-0007). JG Abraldes was a recipient of a grant from Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (01/9356). The authors are indebted to Ms MA Baringo, L Rocabert, and R Saez for expert technical assistance in these studies.

Abbreviations

PPG, portal pressure gradient

HBF, hepatic blood flow

HR, heart rate

TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

CI, cardiac index

REFERENCES

- 1.LaBerge JM, Ring EJ, Gordon RL, et al. Creation of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts with the wallstent endoprosthesis: results in 100 patients. Radiology 1993;187:413–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossle M, Haag K, Ochs A, et al. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt procedure for variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med 1994;330:165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ochs A, Rossle M, Haag K, et al. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt procedure for refractory ascites. N Engl J Med 1995;332:1192–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richter GM, Noeldge G, Palmaz JC, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portacaval stent shunt: preliminary clinical results. Radiology 1990;174:1027–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casado M, Bosch J, Garcia-Pagan JC, et al. Clinical events after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: correlation with hemodynamic findings. Gastroenterology 1998;114:1296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LaBerge JM, Somberg KA, Lake JR, et al. Two-year outcome following transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for variceal bleeding: results in 90 patients. Gastroenterology 1995;108:1143–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lind CD, Malisch TW, Chong WK, et al. Incidence of shunt occlusion or stenosis following transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement. Gastroenterology 1994;106:1277–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaBerge JM, Ferrell LD, Ring EJ, et al. Histopathologic study of stenotic and occluded transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1993;4:779–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Escorsell A, Garcia Pagan JC. Tips in the prevention of variceal rebleeding. Results of randomized controlled trials. In: Arroyo V, Bosch J, Bruguera M, et al, eds. Treatments in Hepatology. Barcelona: Masson, 1999:25–30.

- 10.Navasa M, Chesta J, Bosch J, et al. Reduction of portal pressure by isosorbide-5-mononitrate in patients with cirrhosis. Effects on splanchnic and systemic hemodynamics and liver function. Gastroenterology 1989;96:1110–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandi JC, Garcia-Pagan JC, Escorsell A, et al. Effects of propranolol on the hepatic hemodynamic response to physical exercise in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 1998;28:677–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Escorsell A, Bordas JM, Castaneda B, et al. Predictive value of the variceal pressure response to continued pharmacological therapy in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Hepatology 2000;31:1061–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosch J, Garcia-Pagan JC. Complications of cirrhosis. I. Portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2000;32:141–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Pagan JC, Escorsell A, Moitinho E, et al. Influence of pharmacological agents on portal hemodynamics: Basis for its use in the treatment of portal hypertension. Semin Liver Dis 1999;19:427–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henderson JM. Surgical treatment of variceal bleeding. In: Arroyo V, Bosch J, Bruguera M, et al, eds. Therapy in liver diseases. The pathophysiological basis of therapy. Barcelona: Masson, 1997:463–8.

- 16.Luca A, Garcia-Pagan JC, de Lacy AM, et al. Effects of end-to-side portacaval shunt and distal splenorenal shunt on systemic and pulmonary haemodynamics in patients with cirrhosis. J Gastroentero Hepatol 1999;14:1112–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarfeh IJ, Rypins EB. Partial versus total portacaval shunt in alcoholic cirrhosis. Results of a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 1994;219:353–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groszmann RJ, Bosch J, Grace ND, et al. Hemodynamic events in a prospective randomized trial of propranolol versus placebo in the prevention of a first variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology 1990;99:1401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feu F, Garcia-Pagan JC, Bosch J, et al. Relation between portal pressure response to pharmacotherapy and risk of recurrent variceal haemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Lancet 1995;346:1056–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luca A, D’Amico G, La Galla R, et al. TIPS for prevention of recurrent bleeding in patients with cirrhosis: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Radiology 1999;212:411–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burroughs AK, Patch D. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Semin Liver Dis 1999;19:457–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papatheodoridis GV, Goulis J, Leandro G, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt compared with endoscopic treatment for prevention of variceal rebleeding: A meta-analysis. Hepatology 1999;30:612–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Tsao G, Grace ND, Groszmann RJ, et al. Short-term effects of propranolol on portal venous pressure. Hepatology 1986;6:101–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosch J, Mastai R, Kravetz D, et al. Effects of propranolol on azygos venous blood flow and hepatic and systemic hemodynamics in cirrhosis. Hepatology 1984;4:1200–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroeger RJ, Groszmann RJ. Increased portal venous resistance hinders portal pressure reduction during the administration of beta-adrenergic blocking agents in a portal hypertensive model. Hepatology 1985;5:97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pizcueta MP, de Lacy AM, Kravetz D, et al. Propranolol decreases portal pressure without changing portocollateral resistance in cirrhotic rats. Hepatology 1989;10:953–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Escorsell A, Ferayorni L, Bosch J, et al. The portal pressure response to beta-blockade is greater in cirrhotic patients without varices than in those with varices. Gastroenterology 1997;112:2012–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosca P, Lee FY, Kaumann AJ, et al. Pharmacology of portal-systemic collaterals in portal hypertensive rats: role of endothelium. Am J Physiol 1992;263:G544–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colombato LA, Spahr L, Martinet JP, et al. Haemodynamic adaptation two months after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in cirrhotic patients. Gut 1996;39:600–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandi JC, Fernandez M, Bernadich C, et al. Hyperkinetic circulation and decreased sensitivity to vasoconstrictors following portacaval shunt in the rat. Effects of chronic nitric oxide inhibition. J Hepatol 1999;31:719–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernadich C, Bandi JC, Piera C, et al. Circulatory effects of graded diversion of portal blood flow to the systemic circulation in rats: role of nitric oxide. Hepatology 1997;26:262–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]