Abstract

Background: Tegaserod has been shown to be an effective therapy for the multiple symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in Western populations. However, little information is available regarding the use of tegaserod in the Asia-Pacific population.

Aims: To evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of tegaserod versus placebo in patients with IBS from the Asia-Pacific region.

Patients: A total of 520 patients from the Asia-Pacific region with IBS, excluding those with diarrhoea predominant IBS.

Methods: Patients were randomised to receive either tegaserod 6 mg twice daily (n=259) or placebo (n=261) for a 12 week treatment period. The primary efficacy variable (over weeks 1–4) was the response to the question: “Over the past week do you consider that you have had satisfactory relief from your IBS symptoms?” Secondary efficacy variables assessed overall satisfactory relief over 12 weeks and individual symptoms of IBS.

Results: The mean proportion of patients with overall satisfactory relief was greater in the tegaserod group than in the placebo group over weeks 1–4 (56% v 35%, respectively; p<0.0001) and weeks 1–12 (62% v 44%, respectively; p<0.0001). A clinically relevant effect was observed as early as week 1 and was maintained throughout the treatment period. Reductions in the number of days with at least moderate abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating, no bowel movements, and hard/lumpy stools were greater in the tegaserod group compared with the placebo group. Headache was the most commonly reported adverse event (12.0% tegaserod v 11.1% placebo). Diarrhoea led to discontinuation in 2.3% of tegaserod patients. Serious adverse events were infrequent (1.5% tegaserod v 3.4% placebo).

Conclusions: Tegaserod 6 mg twice daily is an effective, safe, and well tolerated treatment for patients in the Asia-Pacific region suffering from IBS and whose main bowel symptom is not diarrhoea.

Keywords: irritable bowel syndrome, tegaserod, Asia-Pacific, double blind study

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a condition where patients experience a variable combination of abdominal pain or discomfort, bloating, and altered bowel function for which there is no organic cause to explain the symptoms. In the absence of a structural or biochemical marker, the diagnostic criteria are symptom based.1 A biophysical model has been proposed to explain the presentation of IBS.2 The current thinking is that while psychosocial factors influence expression, the symptoms themselves are related to physiological disturbances in motility and visceral perception. As the enteric nervous system plays an important role in regulating these functions, and as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) (serotonin) is a key enteric neurotransmitter, 5-HT receptors have been targeted in the development of pharmacological agents for the treatment of IBS symptoms.3 In particular, the 5-HT4 receptor expressed in the gastrointestinal tract plays a key role in motility—for example, affecting the peristaltic reflex4; moreover, there is growing evidence for a moderating function in visceral pain.5,6

Tegaserod (Zelmac; Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland) is an aminoguanidine-indole compound that acts as a partial selective agonist at the 5-HT4 receptor.7 The pharmacological properties of tegaserod suggest that it normalises altered gastrointestinal motility, and pharmacodynamic studies in animals and humans suggest that it has a promotility effect of accelerating small intestinal and colonic transit8–12 as well as an antinociceptive effect of reducing the sensory response to intestinal distension.5,13 In phase II trials, doses of 2 mg twice daily and 6 mg twice daily were observed to be the most effective doses.14,15

The pivotal clinical trials for IBS drugs have been largely conducted in Europe and the USA. These studies usually employ the Rome criteria16 for patient selection, which consist of descriptive symptoms derived from observations in Western countries; as such, they are subjective and open to interpretation. Furthermore, strict selection criteria in these studies limit their generalisability. In clinical practice, patients often do not fall into the neat categories employed in clinical trials. For example, patients are often selected according to their predominant bowel habit. However, clinical experience shows that the predominant bowel habit is not stable and often alternates between constipation and diarrhoea.17,18 Thus while tegaserod has been shown to be effective and safe in constipation predominant IBS, it is important to evaluate it in a wider IBS group. In Asia-Pacific there is a perception that patients are more bothered by diarrhoea than constipation.19 This study was designed to investigate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of tegaserod in the treatment of IBS in patients from the Asia-Pacific region, excluding those with diarrhoea predominant IBS.

METHODS

This was an 18 week randomised, double blind, parallel group, multicentre study conducted in the Asia-Pacific region in patients with IBS, excluding those whose altered bowel habit was predominantly diarrhoea. The study consisted of a two week baseline period without medication, a 12 week randomised double blind treatment period with either placebo or tegaserod 12 mg/day (given as 6 mg twice daily), followed by a further four week withdrawal period with no medication. The study was conducted between 23 February 2001 and 19 February 2002.

Patients

A total of 670 patients at 57 centres were enrolled in the study. Of these, 520 patients were randomised to receive treatment (259 patients in the tegaserod group and 261 patients in the placebo group) (fig 1 ▶). Reasons for non-randomisation included insufficient symptoms, unwillingness to abstain from disallowed medications (namely antidepressants or laxatives), and presence of concurrent medical conditions. Randomisation was performed using a validated computer system. All personnel involved in the study remained blinded until the database was locked. Male or female patients, aged 18 years or over, with IBS diagnosed using the Rome criteria16 were included in the study. Inclusion into the double blind treatment period was also dependent on responses to assessment of the patients’ IBS symptoms and bowel habits during the baseline period. Patients were excluded from the study for the following reasons: if the mean score for abdominal pain/discomfort was ≤1.0 on a four point scale during the baseline period; if they were considered to be suffering from IBS with diarrhoea; if they had a history of organic disease of the gastrointestinal tract; severe laxative dependence; regular use of medications that could affect gastrointestinal motility and/or perception; use of other investigational drugs; and the presence of any disease likely to compromise the patient’s ability to complete the study or that would significantly affect bowel motility. Medications affecting gastrointestinal motility and or visceral perception, antidepressants, especially tricyclics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, opioids, narcotic analgesics, and antispasmodic agents were not permitted during the study. Laxatives were not permitted during the study; however, patients could receive laxatives (and antidiarrhoeals) as rescue medication.

Figure 1.

Summary of patient disposition by treatment group (all randomised patients, n=520).

The primary efficacy variable was the patient’s response over the first four weeks of double blind treatment to the following question: “Over the past week, do you consider that you have had satisfactory relief from your symptoms of IBS?” (Yes/No). Patients were instructed that “satisfactory” in this context meant that in comparison with their typical experience of the disease in the past, the patient felt that the symptoms of IBS had been alleviated during that week to the extent that they would take a medication to maintain that state, even if no medication was actually being taken at that time.

The secondary efficacy variables were measured daily during the first four weeks and during the entire 12 weeks of the double blind treatment period. These variables included abdominal pain/discomfort, abdominal bloating, stool frequency, stool consistency, urgency, straining, and sensation of complete evacuation. Patients recorded their symptoms in a paper diary on a daily basis. The response to the question used in the primary efficacy over the whole 12 week treatment period was also considered a secondary efficacy variable.

Safety was assessed by recording of all adverse events, and assessment of haematology and blood chemistry parameters, vital signs, and physical examinations before and after the double blind treatment period.

Statistical methods/data analysis

Sample size.

According to the sample size calculation performed before the study was undertaken, 173 evaluable patients per treatment group were needed to detect a difference of 12.5% in the response rates at the 5% significance level with 80% power. This assumed a placebo response rate of 32.5% and a uniform within patient correlation of 0.64.

Primary efficacy.

The short term (four week) response profile analyses of overall assessment of satisfactory relief from IBS symptoms were evaluated using generalised estimating equation analysis, with treatment, time (repeated), and country as factors in the model, and age, body weight, and mean baseline abdominal pain as covariates.

Secondary efficacy.

The long term (12 week) response profiles were analysed as above. Other secondary efficacy variables were evaluated weekly and over weeks 1–4 and 1–12 using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests, adjusted for centre effect. Safety variables were analysed descriptively.

Responder analysis was performed to support the primary efficacy analysis. Patients with a duration of exposure to study medication of at least 28 days were defined as short term responders if at least 75% of their responses over weeks 1–4 were affirmative. The same principle was used to define long term responders over weeks 1–12. This definition of responders follows the recommendations of the Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products.20 Secondary efficacy variables were normalised to a 28 day interval. Where values were recorded for less than 28 days, normalisation was carried out as follows: 28× (number of bowel movements recorded during the 28 day period/number of days with a bowel movement score recorded during the 28 day period).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

There were no clinically significant differences between the treatment groups for any of the key demographic features (table 1 ▶). Of the 520 randomised patients, 447 (86.0%) completed the treatment period and 433 (83.3%) completed the treatment and withdrawal periods. A total of 87 patients (16.7%) discontinued prematurely: 73 patients (14.0%) discontinued during the treatment period and 14 patients (2.7%) discontinued during the withdrawal period.

Table 1.

Demographic data, disease background, and other clinical information by treatment group (intention to treat population, n=520)

| Tegaserod (n=259) | Placebo (n=261) | |

| Sex (n (%)) | ||

| Male | 33 (12.7) | 29 (11.1) |

| Female | 226 (87.3) | 232 (88.9) |

| Race (n (%)) | ||

| Caucasian | 42 (16.2) | 43 (16.5) |

| Chinese | 88 (34.0) | 88 (33.7) |

| Indian | 4 (1.5) | 7 (2.7) |

| Indonesian | 4 (1.5) | 2 (0.8) |

| Korean | 71 (27.4) | 68 (26.1) |

| Malaysian | 11 (4.2) | 9 (3.4) |

| Philippines | 8 (3.1) | 9 (3.4) |

| Thai | 30 (11.6) | 32 (12.3) |

| Other | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.1) |

| Age (y) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 35.9 (12.4) | 36.0 (12.4) |

| Median | 35.0 | 33.0 |

| Weight (kg) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 57.6 (9.2) | 57.7 (10.7) |

| Median | 56.0 | 55.6 |

| Duration of IBS symptoms (months) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 86.3 (77.0) | 96.5 (96.8) |

| Median | 60.0 | 63.0 |

Most patients were female (88.1%) and approximately half of all patients were aged 18–34 years. The largest racial group was Chinese (33.8%). Median duration of IBS was similar in both groups.

There were no important differences between treatment groups with respect to the incidence and daily symptoms recorded at baseline (table 2 ▶). In the intention to treat (ITT) population (all randomised patients), 119 patients (22.9%) used laxative rescue medication during the baseline period; the treatment groups were similar in this respect (53 patients (20.5%) in the tegaserod group and 66 patients (25.3%) in the placebo group). No patient used antidiarrhoeals during the baseline period.

Table 2.

Summary of daily diary data at baseline, normalised to 28 days (intention to treat population, n=520)

| Tegaserod (n=259) | Placebo (n=261) | |

| Stool frequency | 20.7 (14.7) | 18.2 (12.1) |

| No of days with at least moderate abdominal pain/discomfort | 15.5 (8.3) | 15.2 (8.0) |

| No of days with at least moderate bloating* | 14.7 (9.7) | 15.0 (9.1) |

| No of days with no bowel movements | 12.6 (7.2) | 14.0 (6.9) |

| No of days with >3 bowel movements | 0.5 (2.6) | 0.2 (0.9) |

| No of days with hard or lumpy stools* | 12.1 (9.7) | 10.8 (9.6) |

| No of days with normal stools* | 13.4 (9.3) | 14.1 (9.6) |

| No of days with urgency* | 19.9 (8.4) | 19.4 (9.2) |

| No of days with straining† | 10.8 (8.9) | 10.6 (8.8) |

| No of days with sense of incomplete evacuation* | 7.1 (8.6) | 6.3 (8.7) |

Values are mean (SD).

*Tegaserod n=259, placebo n=260.

†Tegaserod n=259, placebo n=259.

At each week during the two week baseline period, more than 99.2% of all patients in both groups recorded unsatisfactory relief from their IBS symptoms.

Overall satisfactory relief from IBS symptoms

Tegaserod caused significant improvement in satisfactory relief of IBS symptoms at the primary end point. Over weeks 1–4, the mean proportions of patients with satisfactory relief were 56% for tegaserod and 35% for placebo. The odds of satisfactory relief were 161% higher in the tegaserod group than in the placebo group (odds ratio 2.61 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.89, 3.61); p<0.0001). Over weeks 1–12, the mean proportions of patients with satisfactory relief were 62% for tegaserod and 44% for placebo. The odds were 139% higher in the tegaserod group (odds ratio 2.39 (95% CI 1.80, 3.18); p<0.0001). As an illustration of the size of the treatment effect, the number needed to treat (NNT) based on the simple proportions of patients with satisfactory relief was calculated.21 At week 4, 63% and 39% of patients treated with tegaserod and placebo, respectively, had satisfactory relief. This is equivalent to an NNT of 4.2 (95% CI 3.1, 6.6). At week 12, 69% and 54% of patients treated with tegaserod and placebo, respectively, had satisfactory relief. This is equivalent to an NNT of 6.6 (95% CI 4.0, 18.6).

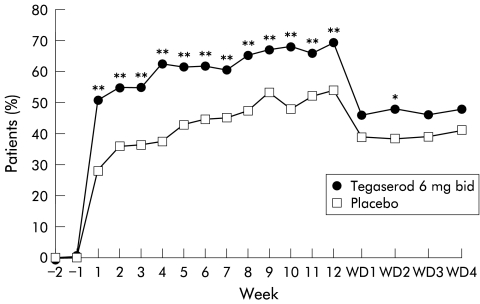

Between treatment comparisons of the response rates for overall satisfactory relief at weeks 1–4 and weeks 1–12 were significantly greater (p<0.01) in the tegaserod group than in the placebo group for both short term and long term responses (fig 2 ▶).

Figure 2.

Responder rates for satisfactory relief in the tegaserod and placebo groups.

The therapeutic gain at week 1 of treatment was 22.5% (50.8% tegaserod v 28.3% placebo) and the gain was sustained over the 12 week treatment period (fig 3 ▶). At all time points from week 1 to week 12, the proportion of patients with satisfactory relief increased above pretreatment values in both treatment groups, most notably in the tegaserod group. At week 12, the therapeutic gain was 15.1% (68.9% tegaserod v 53.8% placebo). During the withdrawal period, the percentage of patients with satisfactory relief was smaller in both groups compared with the treatment period but remained greater in the tegaserod group compared with the placebo group. In the tegaserod group, the response rate decreased from 68.9% at week 12 to 46.9% (mean value) during the four week withdrawal period.

Figure 3.

Summary of affirmative responses (yes) to the overall assessment of satisfactory relief from symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (intention to treat population, n=520). *p<0.05, **p<0.01 versus placebo. WD, withdrawal period.

Additional analysis of satisfactory relief showed that in the subgroups considered (age, weight, number of bowel movements normalised to a 28 day period, sex), the data were generally similar to the total ITT data. The mean proportions of male patients with satisfactory relief during weeks 1–4 were 56% for tegaserod and 46% for placebo. However, for weeks 1–12, there was no difference between the treatment groups (mean proportion was 64% in each treatment group). There was no evidence of a country by treatment interaction.

Compared with baseline, reductions in the number of days with at least moderate abdominal pain/discomfort in the last 28 days were 1.5 days greater in the tegaserod group compared with the placebo group (95% CI −0.2 to 3.2; p=0.0134). Reductions in the occurrence of “no bowel movements” and “hard or lumpy stools” over weeks 1–4 were 1.7 and 3.9 days greater in the tegaserod group than in the placebo group (95% CI 0.8–2.6 (p=0.0002) and 2.3–5.6 (p<0.0001), respectively).

In general, reductions in abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating, stool consistency, and the number of days with no bowel movements were significantly greater in the tegaserod group than in the placebo group at most weeks during the treatment period. However, few significant differences were observed for changes in urgency, number of days with a sensation of incomplete evacuation or normal stools (score of 3, 4, or 5 on the Bristol stool form scale22), or straining. The results for weeks 1–4 and the last 28 days of treatment are presented in table 3 ▶.

Table 3.

Summary of secondary variables derived from the daily diary data: mean absolute change from baseline (number of days) normalised to a 28 day interval (intention to treat population, n=520)

| Mean absolute change | ||||||

| Weeks 1–4 | Last 28 days | |||||

| Tegaserod (n=259) | Placebo (n=253) | Difference (95% CI) [p value] | Tegaserod (n=253) | Placebo (n=253) | Difference (95% CI) [p value] | |

| At least moderate abdominal pain/discomfort | −4.2 | −2.8 | −1.3 (−2.8,0.2) [0.1029] | −7.4 | −5.7 | −1.5 (−3.2,0.2) [0.0134] |

| At least moderate bloating | −3.9* | −2.4† | −1.3 (−2.8,0.2) [0.0825] | −6.1 | −4.7† | −1.2 (−3.0,0.5) [0.2624] |

| No of bowel movements | −4.5 | −2.8 | −1.7 (−2.6,−0.8) [0.0002] | −4.2 | −3.8 | −0.3 (−1.3,0.8) [0.4018] |

| >3 bowel movements | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 (−0.3,0.5) [0.1933] | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.1 (−0.2,0.4) [0.4778] |

| Hard or lumpy stools | −6.6 | −2.6‡ | −3.9 (−5.6,−2.3) [<0.0001] | −6.8 | −4.2§ | −2.5 (−4.2,−0.9) [0.0200] |

| Normal stools | 3.2 | 2.6‡ | 0.6 (−1.2,2.3) [0.6257] | 5.5 | 4.4 | 1.0 (−0.9, 2.8) [0.8902] |

| Urgency | −2.0‡ | −0.7† | −1.2 (−2.7,0.2) [0.2828] | −0.7† | 0.0† | −0.7 (−2.3,1.0) [0.9790] |

| Straining | 4.6* | 2.8‡ | 1.7 (0.1,3.4) [0.0234] | 5.9 | 5.0‡ | 0.7 (−1.2,2.6) [0.2172] |

| Sensation of incomplete evacuation | 2.9* | 1.5† | 1.4 (0.0, 2.8) [0.0754] | 3.9 | 2.6† | 1.3 (−0.4,3.0) [0.2877] |

*n=253; †n=252; ‡n=251; §n=250.

More patients in the placebo group than in the tegaserod group used laxatives during the treatment period (34.1% v 23.2%, respectively).

Tolerability

In total, 268 patients (51.5%) experienced an adverse event (AE) that occurred after the start of treatment (approximately half of the patients in each treatment group). The most common AEs reported during the treatment period, drug related or not, are shown in table 4 ▶. The most frequent AE was headache (12.0% in the tegaserod group and 11.1% in the placebo group). In general, both treatment groups were similar with respect to the type and frequency of AEs during treatment, although diarrhoea and abdominal pain were more frequent in the tegaserod group (diarrhoea 10.0%, abdominal pain 5.8%) than in the placebo group (diarrhoea 3.1%, abdominal pain 3.1%).

Table 4.

Number (%) of patients with the most common adverse events during the treatment period (whether or not drug related, >3%)

| Adverse event | Tegaserod (n (%)) | Placebo (n (%)) |

| Headache | 31 (12.0) | 29 (11.1) |

| Diarrhoea | 26 (10.0) | 8 (3.1) |

| Abdominal pain (not specified) | 15 (5.8) | 8 (3.1) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 15 (5.8) | 20 (7.7) |

| Nausea | 11 (4.2) | 9 (3.4) |

| Dizziness | 10 (3.9) | 9 (3.4) |

| Pyrexia | 9 (3.5) | 4 (1.5) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 7 (2.7) | 8 (3.1) |

| Abdominal distension | 6 (2.3) | 8 (3.1) |

| Abdominal pain, upper | 6 (2.3) | 11 (4.2) |

During the first week of the withdrawal period, 18 patients (6.9%) in the tegaserod group and eight patients (3.1%) in the placebo group experienced an AE. During the entire withdrawal period, 43 patients (16.6%) in the tegaserod group and 35 patients (13.4%) in the placebo group experienced an AE. There were no important differences in the AE profile between the treatment groups during the entire withdrawal period.

The pattern of AE data for female patients in the safety population was in agreement with data for the total safety population. No deaths occurred during this study. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were infrequent (13 patients (2.5%)), and occurred at a greater frequency in the placebo group (nine patients (3.4%)) than in the tegaserod group (four patients (1.5%)). No patients in the tegaserod group discontinued due to SAEs compared with four patients (1.5%) in the placebo group, although discontinuations due to non-serious AEs were more frequent in the tegaserod group (20 patients (7.7%)) than in the placebo group (four patients (1.5%)). The most frequent non-serious AEs which led to discontinuation during the treatment period were diarrhoea (2.3% tegaserod v 0% placebo), abdominal pain (1.5% tegaserod v 0% placebo), and nausea (1.2% tegaserod v 0% placebo). Headache as a reason for discontinuation was reported by 1.2% and 0.4% of patients in the tegaserod and placebo groups, respectively. Laboratory and vital signs data were unremarkable.

DISCUSSION

This is the first large multicentre randomised controlled study of IBS conducted in the Asia-Pacific region. The simplified Rome II criteria were used to select patients for treatment and this study demonstrates the usefulness of these criteria for selecting patients for treatment outside of Europe and the USA. The study employed less restrictive patient selection criteria than those used in the study of Müller-Lissner and colleagues,23 excluding only those with diarrhoea predominant IBS. An overall assessment of satisfactory relief response was used as the primary end point.

These data demonstrate the therapeutic advantage of tegaserod over placebo in this patient population. The degree of relief afforded by tegaserod compared with placebo in this Asia-Pacific IBS population study is in agreement with data from a European population with IBS characterised by abdominal pain, bloating, and constipation (46.3% of patients taking tegaserod 6 mg twice daily were considered responders compared with 34.5% of patients taking placebo).23 In a US population, the response rates at week 4 for tegaserod and placebo were 40.5% and 26.2%, respectively.24

The results show an advantage for tegaserod in patient overall assessment of response. The use of overall satisfactory relief from IBS symptoms as the primary end point is important because of the wide and varied symptomatology of IBS, and the varying importance that patients place on particular symptoms.25 This helps to overcome the disadvantages of symptom score systems, which measure the physical experience of individual symptom relief but do not address the impact of this on global well being and do not capture the importance of particular symptoms to the patient.

Increases in the number of patients who achieved satisfactory relief from their IBS symptoms were observed in both treatment groups, with the improvement being clinically relevant and statistically significantly greater in the tegaserod 6 mg twice daily group than in the placebo group over both weeks 1–4 and weeks 1–12. The therapeutic gain achieved over placebo was observed as early as week 1 of the treatment period, and was sustained during all 12 weeks of treatment; at week 12, a clinically relevant therapeutic gain of 15.1% was recorded. The overall satisfactory relief data were supported by analysis of responder rates.

Patients included in this study reflected the sex mix associated with this disease, and presented the typical profile of IBS symptoms (abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating, and altered stool frequency and consistency). The 62 male patients (11.9% of the study population) did not permit any conclusions to be drawn on the efficacy of tegaserod in men.

Careful trial design is essential for ensuring the generation of quality data in IBS studies.26–28 It has been argued that the use of single assessment variables in previous trials has not provided an accurate reflection of overall symptom improvement, or that the use of global assessments have not allowed the multiple symptoms of IBS to be captured. Through the use of an overall assessment of satisfactory relief from IBS symptoms over the first four weeks and weeks 1–12 of treatment, plus measurement of each IBS symptom over the 12 week treatment period, this study has overcome the limitations of previous studies.

A relatively high placebo response that showed a tendency to rise during the treatment period was recorded in this study. However, this is commonly observed in IBS clinical trials, and the size of the response in the current study was comparable with that reported in a meta-analysis of 25 IBS clinical trials (47% (range 0–84%)).28 Such placebo responses, including tendencies for the response to rise over 9–12 weeks, may reflect the natural progression of a disease that can fluctuate in severity over time or the influence of other factors such as psychological influence on patients’ perceptions of relief.23,29

The safety data are particularly important. As IBS is not a life threatening condition, the profound impact on quality of life notwithstanding, treatments have to be much safer than might be acceptable for other conditions. Several factors make the IBS patient particularly vulnerable: the temptation to try any new drug because of a lack of proven effective medications; the instability of IBS symptoms; insufficient understanding of the pathophysiology; and the psychological issues associated with the condition.

In this Asia-Pacific study, the overall incidence of adverse events was low. Headache was the most commonly reported side effect, but this was not statistically significantly greater with tegaserod (12.0%) than with placebo (11.1%). Headache is a recognised extraintestinal symptom often reported by IBS patients. Whorwell and colleagues30 observed that 31.0% of IBS patients experienced headaches, significantly more than the control group (7.0%), and more than the tegaserod treated patients in this study. The only adverse event that was assessed as drug related by the investigators and occurred significantly more frequently in tegaserod than in placebo treated patients during the treatment period was diarrhoea (6.6% v 1.1%, respectively). Despite the fact that in this trial treatment was not restricted to patients with constipation predominant IBS, the 10.0% incidence of diarrhoea, regardless of causality, as reported by tegaserod treated patients, is similar to that observed in Müller-Lissner’s study.23 The diarrhoea experienced by patients from the Asia-Pacific region also appeared to be mild as it led to discontinuation in only 2.3% of patients. When tegaserod was given to IBS patients with diarrhoea, diarrhoea was also reported to be mild, with only 6% of patients discontinuing treatment.31 No deaths occurred and the incidence of SAEs was low overall and greater in the placebo group than in the tegaserod group. There was no evidence to suggest any specific drug related safety issues in this patient population. Tegaserod has been shown to be devoid of electrocardiographic effects.32

The results support the use of the 6 mg twice daily dose of tegaserod as an effective, safe, and well tolerated dose for use in the Asia-Pacific region in patients with IBS, whose main bowel symptom is not diarrhoea. Tegaserod had a clinically relevant early onset of effect that was sustained over the treatment period.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND AFFILIATIONS

This study was funded by Novartis Asia Pacific, Singapore and Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. The authors would like to thank Frances Dillon and Katherine Hodges from ACUMED for their editorial contribution to the manuscript.

Investigators: Australia. I Roberts-Thomson; R Fraser; G Hebbard; T Florin; N Yeomans; A Duggan; M Ngu; P Gibson; J Kellow; J Karrasch. Hong Kong. J Sung; W Hu; H Yuen. Indonesia. H Ontoseno; D Djojoningrat. Korea. HY Jung; JJ Kim; CS Shim; MG Choi; SH Park; OY Lee; SY Seol; HJ Park; YT Bak; HJ Kim; YH Na; SK Kim; JS Rew; SJ Youn; JH Choi. Malaysia. YC Chia; ST Kew; P Chelvam; MZ Mazlam. New Zealand. A Fraser; J Wyeth; D Shaw. The Philippines. FM Zano; VI Gloria; JD Sollano; EV Valdellon; RS Mercado. Singapore. NM Law; TM Ng; KA Gwee. Taiwan. FY Chang; YC Chao; PC Chen; JT Lin; WW Wu; TT Chang. Thailand. V Mahachai; S Chakkaphak; S Thongsawat; S Leelakusolvong; B Ovartlarnporn; M Hongsirinirachorn; S Surangsrirat; C Pramoolsinsap.

Abbreviations

AE, adverse event

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome

5-HT4, 5-hydroxytryptamine (type 4) receptor

ITT, intention to treat

NNT, number needed to treat

SAE, serious adverse event

REFERENCES

- 1.Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, et al. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut 1999;45(suppl 2):II43–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drossman DA, Whitehead WE, Camilleri M. Irritable bowel syndrome: A technical review for practice guideline development. Gastroenterology 1997;112:2120–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gershon MD. Review article: role played by 5-hydroxytryptamine in the physiology of the bowel. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999;13(suppl 2):15–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grider JR, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Jin J-G. 5-hydroxtryptamine4 receptor agonists initiate the peristaltic reflex in human, rat and guinea pig intestine. Gastroenterology 1998;115:370–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schikowski A, Thewissen M, Mathis C, et al. Serotonin type-4 receptors modulate the sensitivity of intramural mechanoreceptive afferents in the cat rectum. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2002;14:221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coelho A-M, Rovira P, Fioramonti J, et al. Antinociceptive properties of HTF 919 (tegaserod), a 5-HT4 receptor partial agonist, on colorectal distension in rats. Gastroenterology 2000;118:A835. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfannkuche HJ, Buhl T, Gamse R, et al. The properties of a new prokinetically active drug, SDZ HTF 919. Neurogastroenterol Motil 1995;7:280. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen A, Camilleri M, Kost LJ, et al. SDZ HTF 919 stimulates canine colonic motility and transit in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997;280:1270–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathis C, Schikowski A, Thewissen M, et al. Modulation of rectal spinal afferent sensitivity via 5-HT4 receptors. Neurogastroenterol Motil 1998;10:459. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Degen L, Matzinger D, Merz M, et al. Tegaserod, a 5-HT4 receptor partial agonist, accelerates gastric emptying and gastrointestinal transit in healthy male subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:1745–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prather CS, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Tegaserod accelerates orocecal transit in patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2000;118:463–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talley NJ. Serotoninergic neuroenteric modulators. Lancet 2001;358:2061–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coffin B, Farmachidi JP, Bastie A, et al. Tegaserod, a 5-HT4 receptor partial agonist, decreases sensitivity to rectal distension in healthy subjects. Gastroenterology 2002;122:A311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langaker KJ, Morris D, Pruitt R, et al. The partial 5-HT4 agonist (HTF 919) improves symptoms in constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion 1998;59(suppl 3):20. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hämling J, Bang CJ, Tarpila W, et al. Titration regimen indicates partial 5-HT4 agonist HTF 919 improves symptoms of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion 1998;59(suppl 3):735. [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Rome II Modular Questionnaire. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ, et al eds. Rome II—the Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders; Diagnosis, Pathophysiology and Treatment: a Multinational Consensus. McLean VA: Degnon Associates, 2000:360.

- 17.Whitehead WE. Patient subgroups in irritable bowel syndrome that can be defined by symptom evaluation and physical examination. Am J Med 1999;107:33–40S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Irritable bowel syndrome in a community: symptom subgroups, risk factors and health care utilization. Am J Epidemiol 1995;142:76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan G, Lu S, Ke M, et al. Epidemiologic study of the irritable bowel syndrome in Beijing: stratified randomised study by cluster sampling. Chin Med J 2000;113:35–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Points to Consider on the Evaluation of Medicinal Products for the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. London: Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products (CPMP). The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, 2002.

- 21.Chatellier G, Zapletal E, Lemaitre D, et al . The number needed to treat: a clinically useful nomogram in its proper context. BMJ 1966;312:426–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Donnell LJ, Virjee J, Heaton. Detection of pseudodiarrhoea by simple clinical assessment of intestinal transit time. BMJ 1990;300:439–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Müller-Lissner SA, Fumagalli I, Bardhan K, et al. Tegaserod, a 5-HT4 receptor partial agonist, relieves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients with abdominal pain, bloating and constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:1655–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novick J, Miner P, Kranse R, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of tegaserod in female patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:1877–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maxton DG, Morris JA, Whorwell PJ. Ranking of symptoms by patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ 1989;299:1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawkey CJ. Irritable bowel syndrome clinical trial design: future needs. Am J Med 1999;107:98–102S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naliboff BD, Fullerton S, Mayer EA. Measurement of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome clinical trials. Am J Med 1999;107:81–4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spiller RC. Problems and challenges in the design of irritable bowel syndrome clinical trials: experience from published trials. Am J Med 1999;107:91–7S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drossman DA. Do psychosocial factors define symptom severity and patient status in irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Med 1999;107:41–50S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whorwell PJ, McCallum M, Creed FH, et al. Non-colonic features of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 1986;27:37–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fidelholtz J, Smith W, Rawls J, et al. Safety and tolerability of tegaserod in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and diarrhea symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1176–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morganroth J, Rueegg P, Dunger-Baldauf C, et al. Tegaserod, a 5-hydroxytryptamine type 4 receptor partial agonist, is devoid of electrocardiographic effects. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2321–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]