Abstract

Background: In the Western world, the incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma has increased over the last 30 years coinciding with a decrease in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori. Trends of increasing oesophageal adenocarcinoma can be linked causally to increasing gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) which can be linked to an increasingly obese population. However, there is no plausible biological mechanism of association between H pylori, obesity, and GORD. Ghrelin, a peptide produced in the stomach, which regulates appetite, food intake, and body composition, was studied in H pylori positive asymptomatic subjects.

Methods: Plasma ghrelin, leptin, and gastrin were measured for six hours after an overnight fast, before and after cure of H pylori in 10 subjects. Twenty four hour intragastric acidity was also assessed.

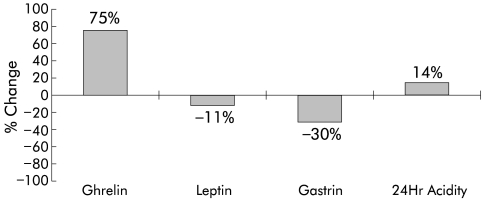

Results: After cure, median (95% confidence intervals) integrated plasma ghrelin increased from 1160.5 (765.5–1451) pg/ml×h to 1910.4 (1675.6–2395.6) pg/ml×h (p=0.002, Wilcoxon’s rank sum test), a 75% increase. This was associated with a 14% increase in 24 hour intragastric acidity (p=0.006) and non-significant changes in leptin and gastrin. There was a significant positive correlation between plasma ghrelin and intragastric acidity (rs 0.44, p=0.05, Spearman’s rank correlation)

Conclusions: After H pylori cure, plasma ghrelin increased profoundly in asymptomatic subjects. This could lead to increased appetite and weight gain, and contribute to the increasing obesity seen in Western populations where H pylori prevalence is low. This plausible biological mechanism links H pylori, through increasing obesity and GORD, to the increase in oesophageal adenocarcinoma observed in the West.

Keywords: ghrelin, leptin, Helicobacter pylori, gastrin, gastric acidity, oesophageal adenocarcinoma

The incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OA) has increased rapidly over the last 30 years. Between 1971 and 1975 in England and Wales, 16 112 people died with OA, rising to 29 743 between 1996 and 2000 (OPCS mortality data for England and Wales). During this period, the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori has decreased. The view that these reciprocal trends of OA and H pylori may be associated is supported by several studies showing that virulent strains of H pylori are found less commonly among patients with Barrett’s oesophagus and OA when compared with controls.1–3 This has led to the suggestion that H pylori colonisation may protect against gastro-oesophageal reflux (GORD) and OA. Others, arguing that there is no plausible biological mechanism, have suggested that the observed trends are purely coincidental.4

Obesity is increasing in incidence and prevalence worldwide, particularly in Western populations. It is accepted that obese individuals have a higher incidence of GORD5; the sphincter mechanism at the oesophagogastric junction is weakened by weight gain leading to gastro-oesophageal acid reflux. GORD leads to the development of Barrett’s oesophagus, a lesion which increases the risk of OA by 40-fold.6,7 In addition, this association has been confirmed by a study showing that individuals with GORD have a relative risk in the order of 43.5 of developing OA.8 Furthermore, there is evidence supporting the notion that increasing body mass is associated with a stepwise increase in the risk of OA.5

Ghrelin, a recently discovered 28 amino acid peptide9 structurally related to motilin,10–12 has been implicated in the control of food intake and energy homeostasis in both humans13 and rodents.14–16 The vast majority of circulating ghrelin is produced in the mammalian gastric mucosa by the enteroendocrine cells/oxyntic glands, probably the X/A-like cells.9 Plasma ghrelin concentrations decrease by 65–77% in patients having undergone gastric bypass surgery.17,18 Ghrelin is also one of the most potent stimulators of growth hormone release acting via the type 1a growth hormone secretagogue receptor19,20; however, its orexogenic effects are independent of growth hormone stimulation.

Regulation of gastric ghrelin secretion is poorly understood. Plasma ghrelin concentrations increase before meals21 and decrease postprandially22 giving it a distinct meal related diurnal profile. Unlike ghrelin, plasma concentrations of anorexogenic polypeptide leptin have not been reported to be acutely affected by meals. The major source of leptin is adipose tissue but more recent reports have shown leptin to be secreted by the stomach.23,24 There is preliminary data to suggest that H pylori may modify gastric mucosal leptin expression25; however, there are no data on ghrelin.

To test our hypothesis, that decreasing H pylori in the population may be causally associated with increasing obesity, and therefore GORD, and the increasing incidence of OA in the Western world, we determined plasma ghrelin and leptin concentration before and after H pylori eradication in healthy subjects. A secondary objective of the study was to determine if there was an association between these hormones and plasma gastrin and intragastric acidity.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Twelve healthy subjects were recruited for the study. They were H pylori positive by serology and the 13carbon urea breath test. They were studied before and a minimum of six weeks after cure of H pylori. During each study, they were admitted onto a research ward at 0700 hours after an overnight fast. An indwelling catheter was inserted into a forearm vein. Blood (10 ml, to which 40 IU of aprotonin were added) was sampled hourly between 0800 and 1300 hours, stored on ice during collection, centrifuged, plasma separated, aliquoted into polypropylene tubes, and stored at −20°C for later analysis. Aliquots were number coded to ensure that the assays were performed blind.

The study conditions were identical on each study day—that is, before and after H pylori cure. During each study, subjects ate a standard breakfast at 0815 hours, which consisted of a glass of fruit juice, a bowl of cereal with milk, two hard boiled eggs, two slices of toast with butter, and two cups of coffee. At 1045 hours they had two cups of tea and two biscuits.

Twenty four hour intragastric acidity was also measured by aspiration of 2–5 ml aliquots of gastric juice via a 10 Fr nasogastric tube hourly between 0800 hours and 0800 hours the next day.

Hormone assays

Plasma immunoreactive ghrelin concentrations were measured in duplicate using a commercial radioimmunoassay (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Belmont, California, USA). The intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was 8.1% and the interassay CV, 9%. The range of detection was 10–1280 pg/ml.

Plasma leptin concentrations were measured using a commercially available leptin radioimmunoassay kit (Linco, USA). The intra-assay CV was 4.9% and the interassay CV 5.3%. The range of detection was 0–100 ng/ml

Plasma gastrin concentrations were performed by an inhouse radioimmunoassay (Professor Bloom’s laboratory, Hammersmith Hospital, Du Cane Road, London, UK). The reference range for this assay in humans is 0–40 pmol/l.

H pylori cure

Immediately after the first study, subjects received a triple regimen, consisting of ranitidine bismuth citrate, 400 mg twice daily, tetracycline hydrochloride 500 mg twice daily, and clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily, for a total of 7 days. The 13carbon urea breath test was repeated a minimum of four weeks after the end of therapy.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Analyse-it for Microsoft Excel (Leeds, UK; see http://www.analyse-it.com). Pairwise comparisons were performed using non-parametric statistical tests (Wilcoxon’s rank sum test). Group data were expressed as median and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Correlation was by Spearman’s rank coefficient test.

Ethical considerations

The Coventry and Warwickshire Research Ethics Committee approved this study. Subjects gave written informed consent.

RESULTS

Ten of the 12 subjects completed the study (males, n=6; females, n=4); median age 36 years (range 27–43) and median body mass index (BMI) 25.8 kg/m2 (range 21–32). Median BMI remained unchanged at the end of the study. H pylori was cured in all 10 subjects.

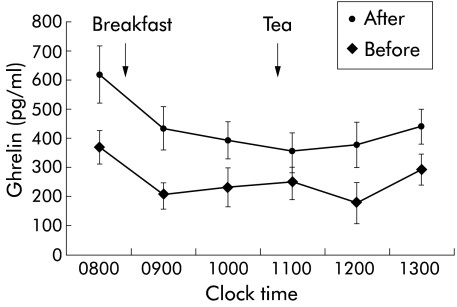

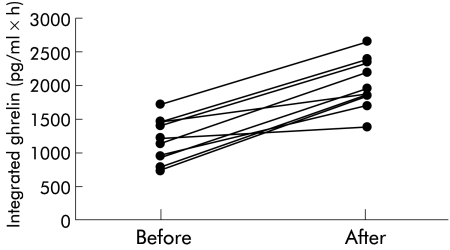

Figure 1 ▶ shows a six hour profile of hourly median plasma ghrelin before and after H pylori cure for the 10 subjects. The profile of plasma ghrelin is as reported by others18,21,22; highest concentration after an overnight fast, decreasing following breakfast, and increasing in anticipation of lunch. After H pylori cure, plasma ghrelin concentrations were raised above the highest concentration recorded before the cure, except at 1100 hours. Figure 2 ▶ shows that six hour integrated plasma ghrelin increased in all 10 subjects after H pylori cure. Median (95% CI) integrated plasma ghrelin increased from 1160.5 (765.5–1451) pg/ml×h to 1910.4 (1675.6–2395.6) pg/ml×h (p=0.002, Wilcoxon’s rank sum test).

Figure 1.

Median (95% confidence intervals) hourly plasma ghrelin concentrations in 10 healthy subjects before and after cure of Helicobacter pylori. Breakfast was at 0815 hours and tea at 1045 hours.

Figure 2.

Six hour integrated plasma ghrelin in 10 healthy subjects before and after cure of Helicobacter pylori.

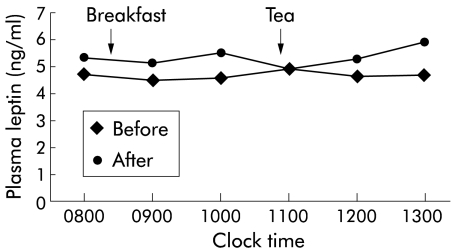

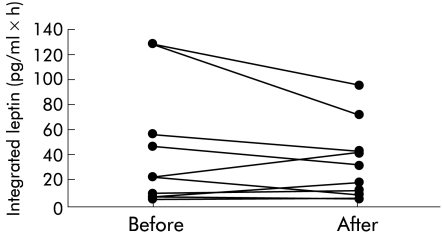

Figure 3 ▶ shows a six hour plasma profile of hourly median plasma leptin before and after H pylori cure for the 10 subjects. Both profiles are similar; typically flat and unaffected by meals. Figure 4 ▶ illustrates six hour integrated plasma leptin for all subjects before and after H pylori cure. Median (95% CI) integrated plasma leptin was 23.66 (7.33–128.22) ng/ml×h before H pylori cure and remained unchanged at 26.75 (7.43–72.81) ng/ml×h after H pylori cure (p=0.375, Wilcoxon’s rank sum test).

Figure 3.

Median hourly plasma leptin concentrations in 10 healthy subjects before and after cure of Helicobacter pylori.

Figure 4.

Six hour integrated plasma leptin in 10 healthy subjects before and after cure of Helicobacter pylori.

Figure 5 ▶ shows the relationship between six hour integrated ghrelin and leptin with six hour integrated gastrin and 24 hour integrated intragastric acidity. The graph shows percentage change in each parameter after Helicobacter pylori cure. After cure, ghrelin and intragastric acidity increased significantly by 75% (p=0.002) and 14% (p=0.006), respectively. Furthermore, a significant positive correlation was noted between ghrelin and intragastric acidity (rs=0.44, p=0.05, Spearman’s rank correlation).

Figure 5.

Six hour integrated values for plasma ghrelin, leptin, gastrin, and 24 hour integrated intragastric acidity, comparing after with before cure of Helicobacter pylori (percentage change). Positive values are increases and negative values are decreases. Ghrelin and acidity increased significantly by 75% and 14%, respectively. Leptin and gastrin decreased non-significantly.

After cure, leptin and gastrin decreased non-significantly by 11% and 30%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have demonstrated for the first time that after successful cure of H pylori in healthy asymptomatic subjects, the median plasma ghrelin concentration increased at each time point throughout the six hour period. In common with previous investigators,21,22 we noted that plasma ghrelin concentrations were highest before a meal, falling shortly after, suggesting that it has a role in meal time hunger. Furthermore, like nutrients such as glucose and amino acids and hormones such as cholecystokinin, ghrelin may play a role in meal initiation. In a randomised double blind crossover study, ghrelin was shown to acutely enhance appetite and increase food intake in healthy human subjects.26 Moreover, our observation that integrated plasma ghrelin was increased by 75% (fig 5 ▶) six weeks after cure of H pylori lends support to the view that ghrelin could be involved in the long term regulation of body weight.15,16 In contrast with ghrelin, the six hour profile of plasma leptin was not significantly changed. Although H pylori modifies leptin expression in the gastric mucosa25 it does not appear to affect plasma leptin concentrations, making it unlikely that any association of H pylori and appetite is mediated through this polypeptide.

The aetiology of common obesity is multifactorial and includes changing lifestyle and diet. However, in rodents, administration of ghrelin leads to an increase in food intake and body weight,16 but also decreases the catabolism of fat.15 It is therefore not inconceivable, given our findings, that subjects cured of H pylori may potentially experience an increase in appetite and in the long term gain weight; an observation particularly relevant in Western populations where the incidence of H pylori is decreasing but that of obesity is increasing reciprocally. This is supported by a study which found that cure of H pylori improved nutritional parameters in patients; body weight, plasma lipid, and albumin concentration increased significantly.27 In our study, we also observed a modest but significant increase in intragastric acidity after cure of H pylori, which could contribute to GORD. Therefore, increasing obesity and GORD would account for the increased incidence of Barrett’s oesophagus and OA, and ghrelin could be the missing link that explains the relative rarity of H pylori among patients with Barrett’s oesophagus and OA and the apparent “protective” effect of H pylori against OA.1,3

It should be noted that there are no studies in adults illustrating whether H pylori positive subjects have a lower BMI than H pylori negative controls. Of interest however are data to suggest that H pylori positive children have a high incidence of growth retardation.28–33 In this context, our findings may be particularly relevant, given that ghrelin stimulates growth hormone secretion in rodents and humans.20 Also, children with H pylori may have relatively low ghrelin concentrations, contributing towards growth retardation. Thus our hypothesis suggests that H pylori positive children may fail to thrive, have a poor appetite, and decreased food intake. They grow up into underweight adults, some of whom will develop peptic ulcer disease, decreasing their food intake further. Finally, a small proportion will develop distal gastric cancer but very few will suffer heartburn or die of OA. This is the typical pattern of foregut disease seen in developing countries with a very high prevalence of H pylori. Conversely, in the developed world, children with no H pylori and relatively high concentrations of plasma ghrelin will grow to their full potential, with a good appetite and increased food intake. They may eventually grow into overweight adults, develop GORD and Barrett’s oesophagus, and in some cases OA. General factors such as lifestyle, diet, and genes would modify these patterns of foregut disease. Specific factors that could contribute to carcinogenesis at the oesophagogastric junction include the direct effect at that site of nitric oxide derived from dietary nitrate.34

The mechanism by which H pylori infection leads to a reduction in plasma ghrelin concentrations remains to be elucidated. There may be a direct effect of H pylori associated inflammation on ghrelin producing cells within oxyntic glands. One possibility is that gastrin may inhibit the release of ghrelin and vice versa. Plasma gastrin decreases following H pylori cure in healthy subjects.35–38 In our study, we did not observe a significant decrease in gastrin as we believe that the post cure study was undertaken too soon to observe complete resolution of H pylori associated hypergastrinaemia. In a recent observation in human subjects, intravenous ghrelin produced a non-significant fall in gastrin, similar to our findings.39 The observed increase in intragastric acidity could contribute to GORD after H pylori cure, and may reflect recovery of parietal cells after resolution of H pylori gastritis. When administered centrally or peripherally to rodents, ghrelin stimulates gastric acid secretion.40 Furthermore, a study in rodents has found ghrelin receptors on gastric vagal afferents which could initiate reflex gastric acid secretion.41 Based on these observations, it is possible that the increased intragastric acidity noted by us may be mediated by ghrelin either via a central pathway or locally given the close juxtaposition of parietal and ghrelin cells in the stomach. This hypothesis is supported by our observation of a significant positive correlation between plasma ghrelin and intragastric acidity.

The limitations of our study need to be addressed. Even though there was a substantial increase in ghrelin in all patients, the study was open and longitudinal in nature, with each subject acting as their own control. It is therefore important for a placebo controlled study not only to confirm our findings but also, if possible, to provide immunohistochemical data on gastric biopsy specimens before and after H pylori cure. Ghrelin administration in rodents causes weight gain via appetite stimulation and reduced fat oxidation15,16; we did not note any change in BMI. With hindsight, we feel that waist circumference and waist to hip ratio may have provided a better picture of fat mass than BMI,42 given the short duration of the study. However, compared with rodents, not much is known of the relationship between ghrelin and the time course of change in body mass and body composition in humans. Certainly, given our findings, a case control study is needed to confirm whether there are differences in body composition between H pylori positive and negative subjects. Another approach would be to measure changes in fat mass, and omental and retroperitoneal fat pads, using sequential dual energy x ray absorptiometry before and after H pylori cure, with long term follow up.

In conclusion, we found that cure of H pylori increased plasma ghrelin in healthy asymptomatic subjects, which in turn may lead to increased appetite and weight gain and contribute to the increasing obesity seen in Western populations where the prevalence of H pylori is low. This study supports the hypothesis that ghrelin may be the missing link between decreasing H pylori, increasing obesity, GORD, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma that is observed in Western populations.

Acknowledgments

EISAI UK provided a grant for measurement of intragastric acidity and gastrin as part of a larger study. We are grateful to Jeanette Burnett and Dr Dimitris Grammatopoulos for help with the leptin and ghrelin assays.

Abbreviations

OA, oesophageal adenocarcinoma

GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux

CV, coefficient of variation

BMI, body mass index

REFERENCES

- 1.Chow W, Blaser M, Blot W, et al. An inverse relation between cagA+ strains of Helicobacter pylori infection and risk of esophageal and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 1998;58:588–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulton-Jones J, Logan R. An inverse relation between cagA-positive strains of Helicobacter pylori infection and risk of esophageal and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Helicobacter 1999;4:281–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimley C, Holder R, Loft D, et al. Helicobacter pylori-associated antibodies in patients with duodenal ulcer, gastric and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999;11:503–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malfertheiner P, Deltenre M, Sipponen P. Helicobacter pylori, the cardia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 1999;15: S57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Nyren O. Association between body mass and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:883–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron A. Epidemiology of columnar-lined esophagus and adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1997;26:487–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spechler S. Disputing dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1607–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, et al. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 1999;340:825–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, et al. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature 1999;402:656–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inui I. Ghrelin: an orexigenic and somatotrophic signal from the stomach. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2001;2:551–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomasetto C, Karam SM, Ribieras S, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel gastric peptide hormone: the motilin-related peptide. Gastroenterology 2000;119:395–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asakawa A, Inui A, Kaga T, et al. Ghrelin is an appetite-stimulatory signal from the stomach with structural resemblance to motilin. Gastroentrology 2001;120:337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wren A, Seal L, Cohen M, et al. Ghrelin enhances appetite and increases food intake in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:5992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wren A, Small C, Abbott C, et al. Ghrelin causes hyperphagia and obesity in rats. Diabetes 2001;50:2540–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tschop M, Smiley DL, Heiman ML. Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature 2000;407:908–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakazato M, Mukakami N, Date Y, et al. A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature 2001;409:194–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ariyasu H, Takaya K, Tagami T, et al. Stomach is a major source of circulating ghrelin, and feeding state determines plasma ghrelin-like immunoreactivity levels in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:4753–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cummings DE, Weigle DS, Frayo RS, et al. Plasma ghrelin levels after diet-induced weight loss or gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1623–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takaya K, Ariyasu H, Kanamoto N, et al. Ghrelin strongly stimulates growth hormone release in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:4908–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Matsuo H, et al. Ghrelin: discovery of the natural endogenous ligand for the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2001;12:118–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings DE, Purnell JQ, Scott Frayo R, et al. A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes 2001;50: 1714–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tschop M, Wawarta R, Riepl R, et al. Post-prandial decrease of circulating human ghrelin levels. J Endocrinol Invest 2001;24:RC19–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider R, Bornstein SR, Chrousos GP, et al. Leptin mediates a proliferative response in human gastric mucosa cell with functional receptor. Horm Metab Res 2001;33:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bado A, Levasseur S, Attoub S, et al. The stomach is a source of leptin. Nature 1998;394:790–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azuma T, Suto H, Ito Y, et al. Gastric leptin and helicobacter pylori infection. Gut 2001;49:324–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wren AM, Seal LJ, Cohen MA, et al. Ghrelin enhances appetite and increases food intake in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:5992–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furuta T, Shirai N, Xiao F, et al. Effect of Helicobacter infection and its eradication on nutrition. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;4:799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richter T, Richter T, List S, et al. Five- to 7-year-old children with Helicobacter pylori infection are smaller than Helicobacter-negative children: a cross-sectional population-based study of 3,315 children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001;33:472–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buyukgebiz A, Dundar B, Bober E, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in children with constitutional delay of growth and puberty. J Pediatr Endocrinol 2001;14:549–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Demir H, Saltik I, Kocak N, et al. Subnormal growth in children with Helicobacter pylori infection. Arch Dis Child 2001;84:89–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jolobe O. Helicobacter pylori infection with iron deficiency anaemia and subnormal growth at puberty. Arch Dis Child 2000;82:136–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sauve-Martin H, Kalach N, Raymond J, et al. The rate of Helicobacter pylori infection in children with growth retardation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1999;28:354–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aggarwal A. Helicobacter pylori infection: a cause of growth delay in children. Indian Pediatr 1998;35:191–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iijima K, Henry E, Moriya A, et al. Dietary nitrate generates potentially mutagenic concentrations of nitric oxide at the gastroesophageal junction. Gastroenterology 2002;122: 1248–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peterson W. Gastrin and acid in relation to Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1996;10(suppl 1):97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witteman E, Verhulst M, de KoR, et al. Basal serum gastrin concentrations before and after eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection measured by sequence specific radioimmunoassays. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1994;8:515–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith J, Pounder R, Nwokolo C, et al. Inappropriate hypergastrinaemia in asymptomatic healthy subjects infected with Helicobacter pylori. Gut 1990;31:522–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prewett E, Smith J, Nwokolo C, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori abolishes 24-hour hypergastrinaemia: a prospective study in healthy subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1991;5:283–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arosio M, Ronchi CL, Gebbia C, et al. Stimulatory effects of ghrelin on circulating somatostatin and pancreatic polypeptide levels. J Clin Endocrine Metab 2003;88:701–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MasudaY, Tanaka T, Inomata N, et al. Ghrelin stimulates gastric acid secretion and motility in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000;276:905–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Date Y, Murakami N, Toshinai K, et al. The role of the gastric afferent vagal nerve in ghrelin-induced feeding and growth hormone secretion in rats. Gastroenterology 2002;123:1120–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Randeva HS, Murray RD, Lewandowski KC, et al. Differential effects of GH replacement on the components of the leptin system in GH-deficient individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:798–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]