Abstract

Background: Gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas are clinically subdivided into Helicobacter pylori dependent and independent, according to H pylori infection and the therapeutic course. In previous reports it has been suggested that H pylori independent cases develop from H pylori dependent cases, and sometimes transform into high grade diffuse large B cell lymphomas (DLBCLs).

Methods: To better understand the pathogenesis of H pylori dependent and independent MALT lymphomas, we analysed the methylation profiles of eight independent CpG islands, including p15, p16, p73, hMLH1, death associated protein kinase, MINT1, MINT2, and MINT31 in H pylori dependent and independent MALT lymphomas, DLBCLs, and H pylori associated chronic gastritis.

Results: We first confirmed that H pylori independent cases had a high incidence of t(11;18)(q21;q21) (4/8 cases) and aberrant BCL10 expression (7/8 cases) compared with H pylori dependent cases and gastric DLBCLs. In the methylation pattern study, all 13 H pylori dependent MALT lymphomas had more than four methylated loci while H pylori independent cases had less than two. According to the previous criterion, all H pylori dependent MALT lymphomas (13/13, 100%) and five of 10 (50%) DLBCLs were classified as CpG island methylator phenotype positive (CIMP+). In contrast, all H pylori independent MALT lymphomas were CIMP−.

Conclusion: The distinct methylation pattern together with lack of chromosomal translocation in H pylori dependent MALT lymphomas suggest that H pylori dependent and independent MALT lymphomas have a different pathogenesis.

Keywords: mucosa associated lymphoid tissue, Helicobacter pylori, methylation, lymphoma

Gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is a definitive clinicopathological entity characterised by its unique histological and clinical features.1 Helicobacter pylori infection is one of the major causes of the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphoma.1,2 Previous reports have shown that most cases of gastric MALT lymphomas arise from H pylori associated chronic gastritis, and that eradication therapy for H pylori is highly effective.1,2 In contrast, some cases of gastric MALT lymphomas show resistance to eradication therapy or absence of H pylori infection, and the growth of those cases is thought to be independent of H pylori.1–4 Some of these cases have been suggested to develop from H pylori dependent MALT lymphomas.5,6 Given the clonal identities of the immunoglobulin heavy chains between low grade MALT lymphomas and coexisting diffuse large B cell lymphomas (DLBCLs) in a considerable number of cases,7,8 MALT lymphomas are, in part, likely to transform into DLBCLs.

Recently, the t(11;18)(q21;q21) translocation, which results in expression of a chimeric transcript fusing the apoptosis inhibitor 2 (API2) and MALT lymphoma translocation 1 (MALT1) genes, has been reported to be present in 30–50% of MALT lymphomas.9–11 Importantly, the t(11;18)(q21;q21) translocation is predominantly found in H pylori independent cases3,11,12 and is rare in H pylori dependent cases and gastric DLBCLs,10–13 suggesting that H pylori independent MALT lymphomas have a distinct pathogenesis. This hypothesis is also supported by the study of BCL10, one of the key molecules in the development of MALT lymphomas, showing that aberrant nuclear localisation of the BCL10 protein is highly frequent in translocation positive MALT lymphomas14 but less frequent in DLBCLs.15

A recent analysis using microsatellite markers in gastric MALT lymphomas has also produced a similar result.16 These findings have compelled us to redefine the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphomas.

In this study, we compared DNA methylation patterns among H pylori dependent and independent MALT lymphomas, gastric DLBCLs, and H pylori associated chronic gastritis to better understand the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphomas. Inactivation of tumour suppressor genes by methylation of the CpG islands is one of the important steps in the development of clinically overt tumours.17 Recent genome wide analyses for DNA methylation in various human tumours has allowed the subclassification of tumours with DNA methylation patterns. The hypermethylated subtype in tumours, also called the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP),18 is a novel marker for tumour progression. Using the CIMP phenotype, we have characterised H pylori dependent and independent MALT lymphomas.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and evaluation of H pylori infection

Twenty one cases of primary low grade gastric MALT lymphomas, 10 cases of gastric DLBCLs, and 10 cases of H pylori associated chronic gastritis were selected at random from patients treated at Jichi Medical School Hospital. The study was approved by the research ethics committee of Jichi Medical School. Clinicopathological data for the low grade gastric MALT lymphomas are summarised in table 1 ▶. All MALT lymphoma cases were in stage IE according to the Ann Arbor staging system. Tumour regression after eradication therapy was histologically evaluated according to the criteria of Wotherspoon and colleagues.1 Patients were followed up by repeated gastric endoscopic biopsies for 3–54 months.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological data for patients with primary low grade gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type lymphomas

| Patient No | Sex | Age (y) | H pylori infection (culture/histology/PCR/serology) | Remission after antibiotic therapy | Follow up period (months) |

| M1 | F | 60 | +/+/+/+ | Complete | 54 |

| M2 | M | 57 | +/+/+/+ | Complete | 36 |

| M3 | F | 41 | +/+/+/ND | Complete | 54 |

| M4 | F | 51 | +/+/+/+ | Complete | 12 |

| M5 | F | 71 | +/+/+/ND | Complete | 33 |

| M6 | M | 69 | +/+/+/+ | Complete | 24 |

| M7 | F | 59 | +/+/+/+ | Complete | 24 |

| M8 | F | 67 | −/+/+/ND | Complete | 3 |

| M9 | M | 46 | +/+/+/ND | Complete | 10 |

| M10 | F | 53 | +/+/+/ND | Complete | 36 |

| M11 | F | 47 | +/+/+/+ | Complete | 6 |

| M12 | M | 44 | +/+/+/ND | Complete | 24 |

| M13 | M | 53 | +/+/+/ND | Complete | 30 |

| M14 | M | 67 | +/+/+/ND | No response | 9 |

| M15 | M | 63 | +/+/+/ND | No response | 19 |

| M16 | M | 53 | −/−/−/− | NT | 42 |

| M17 | F | 51 | −/−/−/− | NT | 12 |

| M18 | M | 59 | −/−/−/− | NT | 12 |

| M19 | F | 55 | −/−/−/− | NT | 12 |

| M20 | M | 60 | −/−/−/− | NT | 1 |

| M21 | M | 73 | −/−/−/− | NT | 1 |

NT, patients were not treated with antibiotics to eradicate H pylori.

ND, not done.

PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

H pylori infection status was evaluated by bacterial culture, histology, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and/or a serum antibody test (GAP test IgG; Biomerica Inc., Newport Beach, California, USA). The PCR conditions and primer sets used in this study have been described previously.19,20 The primer sets used for this analysis are listed in table 2 ▶. As shown in table 1 ▶, these independent analyses gave almost identical results for H pylori infection. Of 21 MALT lymphomas, cases M1–M15 were accompanied by H pylori infection and were treated by eradication therapy. In the remaining cases (patients M16–M21), tests for H pylori infection were completely negative during the follow up period. After successful eradication therapy, we followed patients by repeated gastric endoscopic biopsies for 3–54 months. In patients M1–M13, lymphomas regressed completely within 3–16 months after eradication and were classified as H pylori dependent, while patients M14–M15 showed no signs of endoscopic or histological changes after eradication. The remaining five cases without H pylori infection were followed for 1–42 months before radiation or chemotherapy. Both H pylori eradication non-responsive and H pylori negative lymphoma cases were grouped together in the H pylori independent group for this study.

Table 2.

List of primer sets used for evaluation of the Helicobacter genus infection, MSP, and RT-PCR

| Name | Sense primer | Antisense primer |

| H pylori | ||

| 1st | 5′-AGGATGAAGGTTTTAGGATT-3′ | 5′-CTGGAGAGACTAAGCCCTCC-3′ |

| 2nd | 5′-ATTACTGACGCTGATTGTGC-3′ | 5′-CTGGAGAGACTAAGCCCTCC-3′ |

| Helicobacter genus | ||

| 1st | 5′-CGTGGAGGATGAAGGTTTTA-3′ | 5′-TACACCAAGAATTCCACCTA-3′ |

| 2nd | 5′-CGTGGAGGATGAAGGTTTTA-3′ | 5′-AATTCCACCTACCTCTCCC-3′ |

| MSP | ||

| p15-M | 5′-GCGTTCGTATTTTGCGGTT-3′ | 5′-CGTACAATAACCGAACGACCGA-3′ |

| p15-U | 5′-TGTGATGTGTTTGTATTTTGTGGTT-3′ | 5′-CCATACAATAACCAAACAACCAA-3′ |

| p16-M | 5′-TTATTAGAGGGTGGGGCGGATCGC-3′ | 5′-GACCCCGAACCGCGACCGTAA-3′ |

| p16-U | 5′-TTATTAGAGGGTGGGGTGGATTGT-3′ | 5′-CAACCCCAAACCACAACCATAA-3′ |

| p73-M | 5′-GGACGTAGCGAAATCGGGGTTC-3′ | 5′-ACCCCGAACATCGACGTCCG-3′ |

| p73-U | 5′-AGGGGATGTAGTGAAATTGGGGTTT-3′ | 5′-ATCACAACCCCAAACATCAACATCCA-3′ |

| hMLH1-M | 5′-TTAATAGGAAGAGCGGATAGC-3′ | 5′-CTATAAATTACTAAATCTCTTCG-3′ |

| hMLH1-U | 5′-TTAATAGGAAGAGTGGATAGTG-3′ | 5′-TCTATAAATTACTAAATCTCTTCA-3′ |

| MINT1-M | 5′-AATTTTTTTATATATATTTTCGAAGC-3′ | 5′-AAAAACCTCAACCCCGCG-3′ |

| MINT1-U | 5′-AATTTTTTTATATATATTTTTGAAGTGT-3′ | 5′-AACAAAAAACCTCAACCCCACA-3′ |

| MINT2-M | 5′-TTGTTAAAGTGTTGAGTTCGTC-3′ | 5′-AATAACGACGATTCCGTACG-3′ |

| MINT2-U | 5′-GATTTTGTTAAAGTGTTGAGTTTGTT-3′ | 5′-CAAAATAATAACAACAATTCCATACA-3′ |

| MINT31-M | 5′-TGTTGGGGAAGTGTTTTTCGGC-3′ | 5′-CGAAAACGAAACGCCGCG-3′ |

| MINT31-U | 5′-TAGATGTTGGGGAAGTGTTTTTTGGT-3′ | 5′-TAAATACCCAAAAACAAAACACCACA-3′ |

| DAP kinase-M | 5′-GGATAGTCGGATCGAGTTAACGTC-3′ | 5′-CCCTCCCAAACGCCGA-3′ |

| DAP kinase-U | 5′-GGAGGATAGTTGGATTGAGTTAATGTT-3′ | 5′-CAAATCCCTCCCAAACACCAA-3′ |

| RT-PCR | ||

| t(11;18)(q21;q21) | 5′-TTCATCCGTCAAGTTCAAGC-3′ | 5′-TTGAACAAAAGGATGTCCAG-3′ |

| 1st | 5′-TTACTCAATGCAGAAGATGA-3′ | 5′-ACTGTAAAACCAATGTGCTG-3′ |

| 5′-CAAGAGGAACTGATTGATACG-3′ | 5′-TTCCTATCAAAAGGGCAACC-3′ | |

| t(11;18)(q21;q21) | 5′-AGCCAGTTACCCTCATCTAC-3′ | 5′-CAGCCAAGACTGCCTTTGAC-3′ |

| 2nd-A | 5′-GGCATCAGCTTTTGGGAAGT-3′ | |

| 5′-AAAGGCTGGTCAGTTGTTTG-3′ | ||

| t(11;18)(q21;q21) | 5′-GAAATAAGGGAAGAGGAGAG-3′ | 5′-CAGCCAAGACTGCCTTTGAC-3′ |

| 2nd-B | 5′-GGCATCAGCTTTTGGGAAGT-3′ | |

| 5′-AAAGGCTGGTCAGTTGTTTG-3′ | ||

| t(11;18)(q21;q21) | 5′-ATTGCAGCCACTGTATTCAG-3′ | 5′-CAGCCAAGACTGCCTTTGAC-3′ |

| 2nd-C | 5′-GGCATCAGCTTTTGGGAAGT-3′ | |

| 5′-AAAGGCTGGTCAGTTGTTTG-3′ |

RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction; MSP, methylation specific PCR.

H heilmannii infection, which has been suggested to be another cause of MALT lymphoma in the stomach,21,22 was not detected by histology or PCR in any of the examined cases (data not shown).

Immunohistochemistry for BCL10

Formalin fixed paraffin embedded sections were pretreated in a microwave oven to recover antigenicity and incubated with an anti-BCL10 antibody (1:80; Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, California, USA). Sections were visualised using the ENVISION method (Dako, Kyoto, Japan)

Reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR and sequencing for t(11;18)(q21;q21)

Total cellular RNA was extracted from formalin fixed paraffin embedded sections using the Pinpoint Slide RNA Isolation System (Zymo Research, California, USA). Then, cDNA was synthesised using a First-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Tokyo, Japan). According to the method of Inagaki et al, multiplex nested PCR analysis was performed to detect t(11;18)(q21;q21).23 PCR for glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and β-actin, which were used as controls to ensure the suitability of the used RNA, was performed on the same cDNA samples. To confirm the breakpoints of the fusion transcripts, direct sequencing was carried out using an ABI PRISM 377 DNA Sequencer (Perkin Elmer, Massachusetts, USA) with the same primers used for PCR amplification.

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from formalin fixed paraffin embedded sections, as described previously.24 Briefly, lymphoma cells or non-neoplastic gastric mucosae were scraped from 3 mm thick paraffin sections using a serial haematoxylin-eosin stained section as a guide, and digested in 50 mmol/l Tris HCl buffer (pH8.5) containing 1 mmol/l EDTA, 200 mg/ml proteinase K, and 0.5% Tween20. After eight hours of incubation at 62°C, Chelex-100 (Bio-Rad) was added to a final concentration of 30%. Samples were then boiled for 10 minutes and centrifuged for five minutes at 12 000 rpm. The liquid phase was used for PCR.

Methylation specific PCR (MSP)

Extracted DNA was subjected to chemical modification using a CpGenome DNA modification kit (Intergen, New York, USA) according to the manufacturer’s manual. MSP was performed using the primer sets listed in table 2 ▶ according to the methods of previous reports.25–28 We analysed for the CIMP using a panel of eight independent CpG islands, including tumour suppressor genes and related genes (p15, p16, p73), a cancer associated gene (death associated protein (DAP) kinase), a mismatch repair gene (hMLH (human Mut L homologue) 1), and three methylated clones (MINT (methylated in tumours) 1, MINT2, MINT31) originally recovered from a colorectal carcinoma cell line.29 Toyota et al described two types of DNA methylation: methylation in a cancer specific manner (type C methylation) and age dependent methylation (type A methylation).18 Methylation of p16, hMLH1, MINT1, MINT2, and MINT31 belonged to type C methylation and offered good discrimination for the CIMP.18,28,30,31 Methylation of p15, p16, p73, hMLH1, and DAP kinase gene was detected in some cases of lymphomas.32–36

RESULTS

Aberrant nuclear BCL10 expression and t(11;18)(q21;q21)

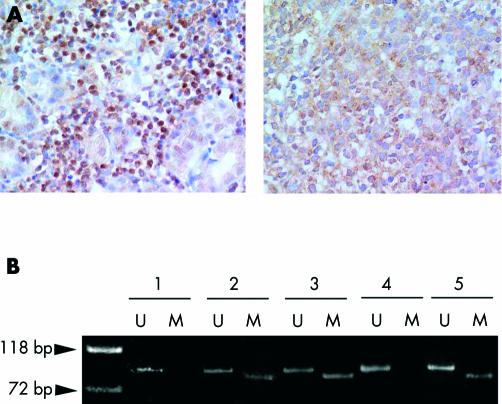

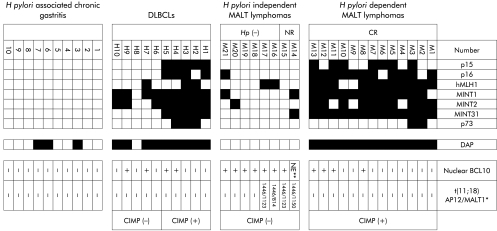

The results of immunohistochemistry, RT-PCR, and the breakpoint of each product are summarised in figs 1A and 2 ▶ ▶. All H pylori independent lymphomas, except for case M14 in which staining was too weak to evaluate BCL10 localisation, showed BCL10 expression predominantly in the nuclei of tumour cells (fig 1A ▶), and 4/8 H pylori independent lymphomas contained t(11;18)(q21;q21) (fig 2 ▶). In contrast, only 4/13 (31%) H pylori dependent MALT lymphomas showed nuclear BCL10 expression. None of the lymphocytes in H pylori associated chronic gastritis showed nuclear BCL10 expression. In DLBCLs, nuclear BCL10 expression was seen in 4/10 (40%) cases. None of the H pylori dependent MALT lymphomas or DLBCLs contained t(11;18)(q21;q21) (fig 2 ▶).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemistry for BCL10 (A) and methylation specific polymerase chain reaction for death associated protein (DAP) kinase CpG island methylation (B). Almost all Helicobacter pylori independent mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas show aberrant nuclear BCL10 expression (A, left), but most H pylori dependent MALT lymphomas showed only cytoplasmic BCL10 expression (A, right). (B) Both aberrant methylated (M) and unmethylated (U) alleles of DAP kinase CpG island were amplified in lanes 2, 3, and 5. Only unmethylated allele was amplified in lanes 1 and 4. lanes 1, 2: H pylori associated chronic gastritis; lane 3: H pylori dependent MALT lymphoma; lane 4: H pylori independent MALT lymphoma; lane 5: gastric diffuse large B cell lymphoma.

Figure 2.

Methylation profile, immunohistochemistry for BCL10, and the results of reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction of Helicobacter pylori dependent and independent mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas, diffuse large B cell lymphomas (DLBCLs), and gastric mucosae with H pylori associated chronic inflammation. Filled boxes indicate methylated loci and open boxes unmethylated loci. Death associated protein (DAP) kinase gene was excluded in defining the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) classification. *Number denotes the breakpoint in API2 and MALT1 according to their DNA sequence (Gene Bank accession No: API2, AF123094; MALT1, NM_006785). **The BCL10 signal was too weak to evaluate nuclear expression. NE, not evaluated; API2, apoptosis inhibitor 2; MINT, methylated in tumours; hMLH, human Mut L homologue.

DNA methylation state of multiple CpG islands

The results of MSP are summarised in fig 2 ▶. Unmethylated alleles of each locus were successfully amplified in all samples examined in this study. Typical results of the MSP are shown in fig 1B ▶. On average, 6.1 (4–8) loci were methylated in the H pylori dependent group in comparison with 0.88 (0–2) loci in the H pylori independent group. No DNA hypermethylation was found in cases of H pylori associated chronic gastritis except for the DAP kinase locus. In defining CIMP+, we excluded DAP kinase, which was methylated in some of the non-neoplastic lesions in this study and previous reports.27 Lymphomas, which showed methylation at three or more of seven loci, were defined as CIMP+, as described previously.18 According to this criterion, all H pylori dependent lymphomas were judged to be CIMP+. In contrast, all H pylori independent lymphomas were CIMP−. Five of 10 DLBCLs (cases H1–5) showed methylation at 5–7 loci and were judged to be CIMP+.

Methylation of DAP kinase gene occurred in all H pylori dependent lymphomas and DLBCLs except for one case (case H8), but in none of the H pylori independent lymphomas. H pylori associated chronic gastritis showed methylation of DAP kinase gene in three cases (cases 3, 6, and 7).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, all H pylori independent MALT lymphomas except for one showed aberrant nuclear localisation of the BCL10 protein, associated with chimeric transcripts of API2/MALT1 in 4/7 cases. Nuclear BCL10 expression without t(11;18)(q21;q21) in some cases might be caused by false negativity of the RT-PCR due to formalin fixation or infiltration of reactive inflammatory cells. In contrast, nuclear localisation of the BCL10 protein was observed in less than 40% of H pylori dependent MALT lymphomas and DLBCLs, and none of the cases expressed the API2/MALT1 chimeric transcripts. These results are identical to previous reports,3,11–14 confirming the importance of chromosomal translocation and aberrant BCL10 expression in the development of H pylori independent MALT lymphomas. On these points, it is clear that H pylori independent MALT lymphomas are distinct not only from H pylori dependent MALT lymphomas but also from gastric DLBCLs.

In the study of DNA methylation using the MSP method, the methylation pattern was markedly different between H pylori independent and dependent cases (fig 2 ▶). The H pylori dependent group was associated with a high level of methylation in comparison with a low level of methylation in the H pylori independent group. Even in the DAP kinase locus, one of the frequently methylated loci in B cell lymphomas, none of the H pylori independent cases showed methylation. These results indicate that the H pylori dependent group was CIMP positive but the H pylori independent group was not. Thus the MSP method seems to be a useful additional tool for the diagnosis of H pylori dependent MALT lymphomas.

It is important to note that hypermethylation at multiple loci of the CpG islands is frequently found in hepatocellular carcinomas with cirrhosis or hepatitis compared with tumours without these conditions.37 In addition, carcinomas or dysplastic epithelium with ulcerative colitis are also associated with a high level of methylation.38–40 In these cases, disorders characterised by increased cell turnover or damage by reactive oxygen species (ROS) attributable to chronic inflammation may increase susceptibility to methylation.38 Some experimental analyses revealed that oxidant induced transformation was associated with aberrant DNA methylation.41,42 On the other hand, H pylori infection has been reported to induce production of ROS by human neutrophils or gastric mucosal cells.43,44 These observations have led us to speculate that certain inflammatory conditions due to H pylori infection cause DNA methylation in reactive lymphocytes, some of which transform into H pylori dependent MALT lymphomas.

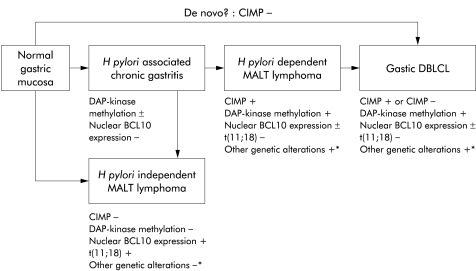

To date, the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphomas is still controversial. Given that low grade MALT lymphomas and DLBCLs showed identical clonality in the rearrangement of immunoglobulin genes,7,8 it was speculated that gastric DLBCLs could arise from H pylori dependent low grade MALT lymphomas via the step of H pylori independent MALT lymphomas.5,6 In contrast, some case reports showed heteroclonalities between coexisting low grade MALT lymphomas and high grade lesions.45,46 Recently, Starostik et al have reported that gastric DLBCLs have similar genetic alterations to t(11;18) negative but not t(11;18) positive MALT lymphomas.16 Accordingly, they have proposed that two distinct pathways are involved in the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphomas.16 In support of their hypothesis, the methylation patterns were completely different between the H pylori dependent and independent cases in this study. Thus characterisation of DNA methylation provides us with a novel aspect for understanding the pathogenesis of MALT lymphomas.

Based on previous reports and our own results,16,47,48 we propose the following model for gastric MALT lymphoma development and progression (fig 3 ▶). H pylori dependent lymphomas arise from H pylori associated chronic gastritis due to genetic alterations, such as p15, p16, and DAP kinase methylation, and 3q26.2–27 amplification,16 but lack t(11;18)(q21;q21). In contrast, H pylori independent MALT lymphomas develop along a pathway determined by nuclear BCL10 expression due to t(11;18)(q21;q21)14 but lack methylation of the CpG islands. Given that half of the DLBCLs showed the CIMP phenotype in this study, it is likely that some cases of H pylori dependent MALT lymphomas without t(11;18)(q21;q21) transform into DLBCLs at progression, and that the residual half of the DLBCLs, which were CIMP− and did not have t(11;18)(q21;q21) in this study, may develop along other pathways such as de novo lymphomagenesis.

Figure 3.

Two distinct pathways for the development of Helicobacter pylori dependent and independent mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas. H pylori dependent MALT lymphomas with the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) tend to lack BCL10 aberration, and some transform into diffuse large B cell lymphomas (DLBCLs). In contrast, H pylori independent MALT lymphomas with aberrant BCL10 expression lack the CIMP (CIMP−) and other genetic aberrations for transformation into DLBCLs. DLBCLs without the CIMP may develop along other pathways such as de novo lymphomagenesis. DAP, death associated protein. *From Starostik and colleagues,16 Bertoni and colleagues,47 and Du and Isaacson.48

In this model, we grouped together H pylori negative lymphomas and lymphomas from H pylori eradication non-responsive cases into the H pylori independent lymphoma group. In our results, both types of lymphomas were CIMP−. Moreover, t(11;18)(q21;q21) was found in both H pylori negative lymphomas and H pylori eradication non-responsive lymphomas in this study and previous reports.3,11,12 Thus it seems reasonable to group both types of lymphomas as H pylori independent although the number of cases in this study was too small to draw definitive conclusions.

In summary, based on studies of DNA methylation, we have shown here that H pylori dependent MALT lymphomas have a distinct methylated phenotype. In contrast, H pylori independent cases have lower methylation patterns, and the frequent MALT specific translocation t(11;18)(q21;q21) in association with aberrant BCL10 expression. Taken together with the results from DLBCLs and H pylori associated chronic gastritis, our results seem to further strengthen the current hypothesis that the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphomas has two distinct pathways.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Hiroshi Inagaki at the Department of Pathology, Nagoya City University Medical School, for the generous donation of positive controls for the multiplex RT-PCR method.

Abbreviations

MALT, mucosa associated lymphoid tissue

DLBCLs, diffuse large B cell lymphomas

CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype

API2, apoptosis inhibitor 2

PCR, polymerase chain reaction

RT, reverse transcriptase

GAPDH, glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

MSP, methylation specific PCR

ROS, reactive oxygen species

DAP, death associated protein

MINT, methylated in tumours

hMLH, human Mut L homologue

REFERENCES

- 1.Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, Diss TC, et al. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet 1993;342:575–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayerdorffer E, Neubauer A, Rudolph B, et al. Regression of primary gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. Lancet 1995;345:1591–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamura T, Nakamura S, Yonezumi M, et al. The t(11;18)(q21;q21) translocation in H pylori-negative low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:3314–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, Lavergne A, Aegerter PH, et al. Predictive factors for regression of gastric MALT lymphoma after anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment. Gut 2001;48:297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Jong D, Boot H, van Heerde P, et al. Histological grading in gastric lymphoma: pretreatment criteria and clinical relevance. Gastroenterology 1997;112:1466–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isaacson PG. Gastric MALT lymphoma. From concept to cure. Ann Oncol 1999;10:637–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montalban C, Manzanal A, Gastrillo JM, et al. Low grade gastric B-cell MALT lymphoma progressing into high grade lymphoma. Clonal identity of the two stages of the tumor, unusual bone involvement and leukemic dissemination. Histopathology 1995;27:89–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peng H, Du M, Diss TC, et al. Genetic evidence for a clonal link between low and high-grade components in gastric MALT B-cell lymphoma. Histopathology 1997;30:425–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Remstein ED, James CD, Kurtin PJ. Incidence and subtype specificity of API2-MALT1 fusion translocations in extranodal, nodal, and splenic marginal zone lymphomas. Am J Pathol 2000;156:1183–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathijs B, Maes B, Steyls A, et al. The product of the t(11;18), an API2-MLT fusion, marks nearly half of gastric MALT type lymphomas without large cell proliferation. Am J Pathol 2000;156:1433–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu H, Ruskon-Fourmestraux A, Lavergne-Slove A, et al. Resistance of t(11;18) positive gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma to Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Lancet 2001;357:39–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugiyama T, Asaka M, Nakamura T, et al. API2-MALT1 chimeric transcript is a predictive marker for the responsiveness of H pylori eradication treatment in low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. Gastroenterology 2001;120:1884–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alpen B, Neubauer A, Dierlamm J, et al. Translocation t(11;18) absent in early gastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type responding to eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Blood 2000;95:4014–4015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu H, Ye H, Dogan A, et al. t(11:18)(q21;q21) is associated with advanced mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma that expresses nuclear BCL 10. Blood 2001;98:1182–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye H, Dogan A, Karran L, et al. BCL 10 expression in normal and neoplastic lymphoid tissue: nuclear localization in MALT lymphoma. Am J Pathol 2000;157:1147–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starostik P, Patzner J, Greiner A, et al. Gastric marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of MALT type develop along 2 distinct pathogenetic pathways. Blood 2002;99:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esteller M, Corn PG, Baylin SB, et al. A gene hypermethylation profile of human cancer. Cancer Res 2001;61:3225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:8681–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho SA, Hoyle JA, Lewis FA, et al. Direct polymerase chain reaction test for detection of Helicobacter pylori in humans and animals. J Clin Microbiol 1991;29:2543–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trebesius K, Adler K, Vieth M, et al. Specific detection and prevalence of Helicobacter heilmannii-like organisms in the human gastric mucosa by fluorescent in situ hybridization and partial 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing. J Clin Microbiol 2001;39:1510–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stolte M, Kroher G, Meining A, et al. A comparison of Helicobacter pylori and H. heilmannii gastritis. A matched control study involving 404 patients. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgner A, Lehn N, Andersen LP, et al. Helicobacter heilmannii-associated primary gastric low-grade MALT lymphoma: complete remission after curing the infection. Gastroenterology 2000;118:821–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inagaki H, Okabe M, Seto M, et al. API1-MALT1 fusion transcripts involved in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Am J Pathol 2001;158:699–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakurai S, Sano T, Nakajima T. Clinicopathological and molecular biological studies of gastric adenomas with special reference to p53 abnormality. Pathol Int 1995;45:51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hermans JG, Graff JR, Myohanen S, et al. Methylation-specific PCR: A novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93:9821–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu M, Taketani T, Li R, et al. Loss of p73 gene expression in lymphoid leukemia cell lines is associated with hypermethylation. Leuk Res 2000;25:441–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang GH, Shim Y-H, Jung H-Y, et al. CpG island methylation in premalignant stages of gastric carcinoma. Cancer Res 2001;61:2847–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan AO, Issa JP, Morris JS, et al. Concordant CpG island methylation in hyperplastic polyposis. Am J Pathol 2002;160:529–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toyota M, Ho C, Ahuja N, et al. Identification of differentially methylated sequences in colorectal cancer by methylated CpG island amplification. Cancer Res 1999;59:2307–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strathdee G, Appleton K, Illand M, et al. Primary ovarian carcinomas display multiple methylator phenotype involving known tumor suppressor genes. Am J Pathol 2001;158:1121–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanai Y, Ushijima S, Kondo Y, et al. DNA methyltransferase and DNA methylation of CpG islands and peri-centromeric satellite regions in human colorectal and stomach cancers. Int J Cancer 2001;91:205–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez DB, Fernandez PJ, Garcia MJ, et al. Hypermethylation of a 5′ CpG island of p16 is a frequent event in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leukemia 1997;11:425–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baur AS, Shaw P, Burri N, et al. Frequent methylation silencing of p15(INK4b) (MTS2) and p16(INK4a) (MTS1) in B-cell and T-cell lymphomas. Blood 1999;94:1173–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawano S, Miller CW, Gombart AF, et al. Loss of p73 gene expression in leukemias/lymphomas due to hypermethylation. Blood 1999;94:1113–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katzenellenbogen RA, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Hypermethylation of the DAP-kinase CpG island is a common alteration in B-cell malignancies. Blood 1999;93:4347–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ping Siu LL, Cheung Chan JK, Wong KF, et al. Specific patterns of gene methylation in natural killer cell lymphomas. Am J Pathol 2002;160:59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen L, Ahuja N, Shen Y, et al. DNA methylation and environmental exposures in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:755–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Issa JP, Ahuja N, Toyota M, et al. Accelerated age-related CpG island methylation in ulcerative colitis. Cancer Res 2001;61:3573–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sato F, Harpaz N, Shibata D, et al. Hypermethylation of the p14ARF gene in ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 2002;62:1148–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsieh CJ, Klump B, Holzmann K, et al. Hypermethylation of the p16INK4a promoter in colectomy of patients with long-standing and extensive ulcerative colitis. Cancer Res 1998;58:3942–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka T, Iwasa Y, Kondo S, et al. High incidence of allelic loss on chromosome 5 and inactivation of p15INK4B and p16INK4A tumor suppressor genes in oxystress-induced renal cell carcinoma of rats. Oncogene 1999;18:3793–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cerda S, Weitzman SA. Influence of oxygen radical injury on DNA methylation. Mutat Res 1997;386:141–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bagchi D, McGinn TR, Ye X, et al. Helicobacter pylori-induced oxidative stress and DNA damage in a primary culture of human gastric mucosal cells. Dig Dis Sci 2002;47:1405–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shimoyama T, Fukuda S, Liu Q, et al. Production of chemokines and reactive oxygen species by human neutrophils stimulated by Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 2002;7:170–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matolcsy A, Nagy M, Kisfaludy N, et al. Distinct clonal origin of low-grade MALT-type and high-grade lesions of a multifocal gastric lymphoma. Histopathology 1999;34:6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cabras AD, Weirich G, Fend F, et al. Oligoclonality of a composite gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with areas of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type. Virchows Arch 2002;440:209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bertoni F, Cavalli F, Cotter FE, et al. Genetic alterations underlying the pathogenesis of MALT lymphoma. Hematol J 2002;3:10–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Du MQ, Isaacson PG. Gastric MALT lymphoma: from aetiology to treatment. Lancet Oncol 2002;3:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]