Abstract

Background: There may be a weak association between total alcohol intake and colorectal cancer but the effect of different types of alcohol and effect on colon subsites have not been investigated satisfactorily.

Aims: To investigate the relationship between amount and type of alcohol and the risk of colon and rectal cancer.

Subjects: A population based cohort study with baseline assessment of weekly intake of beer, wine, and spirits, smoking habits, body mass index, educational level, and leisure time physical activity in Copenhagen, Denmark. The study included a random sample of 15 491 men and 13 641 women, aged 23–95 years. Incident cases of colorectal cancer were identified in the nationwide Danish Cancer Register.

Results: During a mean follow up of 14.7 years, we observed 411 colon cancers and 202 rectal cancers. We observed a dose-response relationship between alcohol and rectal cancer. Drinkers of more than 41 drinks a week had a relative risk of rectal cancer of 2.2 (95% confidence limits 1.0–4.6) compared with non-drinkers. Drinkers of more than 14 drinks of beer and spirits a week, but not wine, had a risk of 3.5 (1.8–6.9) of rectal cancer compared with non-drinkers, while those who drank the same amount of alcohol but including more than 30% of wine had a risk of 1.8 (1.0–3.2) of rectal cancer. No relation between alcohol and colon cancer was found when investigating the effects of total alcohol, beer, wine, and spirits, and percentage of wine of total alcohol intake.

Conclusion: Alcohol intake is associated with a significantly increased risk of rectal cancer but the risk seems to be reduced when wine is included in the alcohol intake.

Keywords: alcohol, colon cancer, rectal cancer, population based study

Despite intensive research, evidence regarding the association between alcohol and colorectal cancer still remains inconclusive.1 A meta-analysis, including five follow up studies and 22 case control studies, reported a weak association between alcohol and colorectal cancer (relative risk of 1.10 (1.05–1.14) when consuming more than two drinks a day), especially for rectal cancer.2 Regarding the carcinogenic role of alcohol, support arises from studies associating alcohol with colorectal hyperplastic polyps and in particular with adenomas, known precursors of colorectal cancer.3,4 Previous studies have confirmed a positive association,5–7 while others have not8 or even found an inverse association.9 One study suggested a difference between colon subsites.9 A number of the prospective studies were conducted in selected groups, such as alcoholics or brewery workers. Therefore, the first aim of this investigation was to examine the effects of alcohol on the risk of proximal colon cancer, distal colon cancer, and rectal cancer in a large sample of the general population.

With regard to beverage specific effects on colorectal cancer, the evidence is even more sparse.2 Recent studies have suggested a strong association, especially with beer intake,5,10,11 although an increased risk has also been related to wine and spirits.6 Previous epidemiological studies of upper digestive cancer and lung cancer in the present study population have drawn attention to an anticarcinogenic property of wine.12,13 Experimental research has supported these results by showing a suppressive effect of flavonoid extracts, especially anthocyanin from red and white wines, on the growth of human colon and gastric cancer cells.14 Furthermore, resveratrol, another natural component of grapes and wine, has also been shown to have antiproliferative effects.15 On the basis of these studies, the second aim of our study was to examine the effects of beer, wine, and spirits on the risk of proximal colon cancer, distal colon cancer, and rectal cancer.

METHODS

Population

The Copenhagen Centre for Prospective Population Studies is based on three comprehensive Danish programmes of prospective population studies: the Copenhagen City Heart Study, the Copenhagen County Centre of Preventive Medicine (formerly, the Glostrup Population Studies) which includes six cohorts, and the Copenhagen Male Study. Detailed descriptions of the studies have been published previously.16–18 Briefly, in the former two, initiated in 1976 and 1964, respectively, subjects were randomly selected within age strata in defined areas in greater Copenhagen. In the Copenhagen Male Study, initiated in 1970, employees of 14 large companies in Copenhagen were invited to participate. The mean participation rate in all studies was 80% (range 69–88%).16–18

All population studies included a self administered questionnaire on various health related issues, such as alcohol intake (including intake of beer, wine, and spirits), smoking habits, education, and leisure time physical activity, and a physical examination. Staff members checked answers to the questionnaire during the examination. All studies combined included 14 662 women and 18 602 men.

Questionnaire

Participants in the Copenhagen Male Study were asked about average daily intake of beer, wine, and spirits on weekdays (Monday–Thursday) and at weekends (Friday–Sunday). Subjects in the Copenhagen City Heart Study and in the Copenhagen County Centre of Preventive Medicine were asked about their average weekly intake of the different types of alcohol. The data were summed to give an average weekly intake. In Denmark, one beer contains 12 g of alcohol, which is considered to be the amount of alcohol in a standard alcoholic drink. Based on data from the questionnaire, participants were placed into one of six groups according to total average weekly alcohol intake: <1, 1–6, 7–13, 14–27, 28–40, and >41 drinks. Non-drinkers were defined as those drinking less than 1 drink a week, which means that non-drinkers included both total abstainers and subjects with a very low alcohol intake. For every beverage type, subjects were categorised into four groups: 0, 1–6, 7–14, and >14 drinks a week.

Answers regarding smoking status were grouped as follows: never smokers, former smokers, current smokers 1–14 g of tobacco/day, current smokers 15–24 g of tobacco/day, and current smokers ≥25 g of tobacco/day. Based on data from the physical examination, body mass index was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m2) and categorised into five groups: <20, 20–25, 25–30, 30–35, and >35 kg/m2. Subjects reported the length of their school education in three categories: <8 years, 8–11 years, and >12 years of education. Regarding leisure time physical activity, subjects reported their level of activity as one of the following four categories: (1) none or very little; (2) moderate, less than four hours per week; (3) moderate, more than four hours per week; and (4) energetic, more than four hours per week.

Study cohort and follow up

With information obtained through record linkage between the present populations and the Cancer Register and the National Patient Register, we excluded subjects with a history of cancer at baseline, except for non-melanoma skin cancer or carcinoma in situ, defined according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), seventh revision,19 codes 140–205 excluding 191, and according to ICD, 10th revision,20 codes C00-C97 excluding C44 (n=812). Subjects with a history of colitis ulcerosa or Mb Crohn defined according to ICD, eighth revision,21 codes 563.01, 563.19, and according to ICD, 10th revision,20 codes K50.0-K51.9 were excluded (n=33). Finally, we also excluded subjects with incomplete information on alcohol intake (n=2647).

Subjects who developed colorectal cancer during follow up were identified through record linkage between the present populations and the Cancer Register and the National Patient Register. Cancers of the colon and rectum were defined as adenocarcinoma according to the ICD, seventh revision19 as 153.0–154.9 and 253.0–253.4 and according to the ICD, 10th revision20 as DC18.0-DC18.9 and DC20.9. Cancer of the proximal colon was defined as from the caecum to the splenic flexure and cancers of the distal colon were from the descending colon to the rectosigmoidal colon.

Vital status was followed until 1 January 1999 using the unique personal identification number in the Civil Registration System. The observation period for each subject was from entry into the study until the time of death, emigration, or disappearance, time of diagnosis of colorectal cancer, or 1 January 1999, whichever came first. Disappearance or emigration was responsible for 0.7% of the study sample being lost to follow up (n=204).

Validity and completeness validity of the Cancer Register

Registration is based on notification forms that are completed by hospital departments (including departments of pathology and forensic medicine) and practising physicians whenever a case of cancer is diagnosed or found at autopsy and whenever there are changes in an initial diagnosis. Cases recorded manually are supplemented by unrecorded cases revealed by computerised linkages to the death certificate files and the National Patient Register.22 The entire process is supervised by medical doctors. Ambiguous or contradictory information, either within a notification form or between forms, leads to queries in approximately 10% of notifications received. Comprehensive evaluation has shown that the Register is 95–99% complete and valid.23–26

Statistical analysis

Cox regression methods were used to estimate the effect of alcohol on colorectal cancer, with age as the underlying time scale and age at examination as entry time. The effect of total alcohol was entered into the model in the previously mentioned six categories, with non-drinkers as the reference category. The effects of beer, wine, and spirits were entered into another model containing all three beverages in four categories (0, 1–6, 7–14, and >14 drinks per week), with non-drinkers of a specific beverage type as the reference category. As non-drinkers of a specific beverage type is composed of both total abstainers and drinkers of either one of the two remaining beverages types or both, further analyses were conducted. Subjects were categorised according to the percentage of wine of their total alcohol intake and their total alcohol intake. A model estimating the effects of beer, wine, and spirits was conducted, with entry of the percentage of wine of the total amount of alcohol (0%, 1–30%, and >30%), and total non-drinkers were the reference group.

Of the possible confounders considered (sex, smoking status, body mass index, study of origin, education, and leisure time physical activity) only those that were independent risk factors and that changed the estimates in the model by 5% were included. Sex, smoking status (five levels), body mass index (four levels), and study of origin (three levels) were found to be confounders using these criteria. Interaction between sex and alcohol intake and interaction between smoking and alcohol intake were investigated by entering the factor and its interaction term in the model. No interactions were found at a significance level of p=0.01. The multivariable models were first applied to the colon and rectal cases separately. Secondly, the multivariable models were applied to proximal and distal colon cancers separately. All analyses were repeated after excluding the first two years of follow up in order to eliminate or reduce the possible impact of selection bias due to the presence of colorectal cancer at the baseline assessments. All analyses were computed using SAS/STAT software.

RESULTS

During a total of 426 934 person years, 411 colon cancers (159 in the proximal colon and 202 in the distal colon) and 202 rectal cancers occurred. Mean follow up was 14.7 years (range 2–23) for the whole study population.

In this population, more males than females were reported to be heavy drinkers (table 1▶). Heavy drinkers were more frequently current smokers and had a higher body mass index than light drinkers. Wine drinkers reported a higher educational level and a higher level of leisure time physical activity than non-wine drinkers.

Table 1 .

Characteristics of the study participants in the present study from the Copenhagen Centre for Prospective Studies, Denmark 1976–1993

| Mean alcohol (drinks/wk) | Male subjects (%) | Mean age (y) | Mean body mass index (kg/m2) | Current smokers (%) | Lowest educational level*(%) | Physically inactive†(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol (drinks/wk) | |||||||

| <1 | 0.0 | 29 | 54 | 26 | 52 | 57 | 28 |

| >1–<7 | 3.5 | 36 | 48 | 25 | 55 | 37 | 19 |

| >7–<14 | 9.7 | 63 | 50 | 25 | 59 | 36 | 17 |

| >14–<28 | 18.9 | 81 | 52 | 25 | 64 | 39 | 17 |

| >28–<41 | 33.0 | 92 | 52 | 26 | 70 | 45 | 22 |

| >41 | 60.0 | 93 | 51 | 26 | 76 | 49 | 27 |

| Beer (drinks/wk) | |||||||

| 0 | 0.0 | 36 | 51 | 25 | 49 | 41 | 25 |

| <1 | 0.2 | 16 | 54 | 25 | 57 | 53 | 21 |

| >1–<7 | 3.0 | 56 | 48 | 25 | 57 | 33 | 18 |

| >7–<14 | 8.6 | 86 | 52 | 25 | 64 | 40 | 17 |

| >14 | 27.3 | 93 | 51 | 26 | 74 | 50 | 24 |

| Wine (drinks/wk) | |||||||

| 0 | 0.0 | 60 | 54 | 25 | 58 | 53 | 26 |

| <1 | 0.1 | 45 | 55 | 26 | 65 | 63 | 27 |

| >1–<7 | 2.8 | 51 | 48 | 25 | 57 | 33 | 16 |

| >7–<14 | 9.3 | 65 | 52 | 25 | 54 | 27 | 16 |

| >14 | 20.8 | 62 | 52 | 25 | 62 | 23 | 17 |

| Spirits (drinks/wk) | |||||||

| 0 | 0.0 | 54 | 48 | 25 | 54 | 38 | 24 |

| <1 | 0.1 | 33 | 53 | 25 | 59 | 54 | 22 |

| >1–<7 | 2.6 | 63 | 49 | 25 | 61 | 37 | 17 |

| >7–<14 | 8.8 | 75 | 60 | 26 | 62 | 47 | 17 |

| >14 | 23.1 | 81 | 57 | 26 | 72 | 45 | 26 |

*The lowest educational level is less than eight years of education.

†Physically inactivity is defined as none or very little physical activity in leisure time.

Total alcohol intake and colon cancer

There was no effect of total alcohol intake on the risk of colon cancer (table 2▶). Hence subjects consuming more than 41 drinks of alcohol a week had an adjusted relative risk of 0.8 (95% confidence limits 0.5–1.5) compared with non-drinkers. A further division of colon cancer into proximal and distal colon cancer did not reveal any difference between the subsites with respect to the influence of alcohol. Subjects with an alcohol intake >41 drinks a week compared with non-drinkers had relative risks of 1.0 (0.4–2.4) and 1.0 (0.4–2.3) for proximal and distal colon cancers, respectively (data not shown).

Table 2 .

Relative risk of colon and rectal cancer according to total weekly alcohol intake in the present study from the Copenhagen Centre for Prospective Studies, Denmark 1976–1993

| Colon |

Rectum |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects (cases) | Relative risk* | 95% CL | Subjects (cases) | Relative risk* | 95% CL | |

| Alcohol | ||||||

| <1 | 5712 (96) | 1.0 | 5712 (28) | 1.0 | ||

| 1–6 | 9722 (129) | 1.0 | 0.8–1.3 | 9722 (60) | 1.5 | 0.9–2.3 |

| 7–13 | 5996 (77) | 0.9 | 0.7–1.2 | 5996 (43) | 1.5 | 0.9–2.5 |

| 14–27 | 4881 (68) | 0.9 | 0.6–1.2 | 4881 (43) | 1.7† | 1.0–2.8 |

| 28–40 | 1663 (27) | 1.1 | 0.7–1.7 | 1663 (17) | 2.1† | 1.1–4.0 |

| ≥41 | 1158 (14) | 0.8 | 0.5–1.5 | 1158 (11) | 2.2† | 1.0–4.6 |

| Trend: p=0.58 | Trend: p=0.03 | |||||

*All adjusted for age, sex, smoking, body mass index, and study of origin.

†p<0.05.

95% CL, 95% confidence limits.

Total alcohol intake and rectal cancer

There was a strong adjusted dose dependent association between alcohol intake and rectal cancer (table 2▶). Drinkers of more than 41 drinks a week had a relative risk of rectal cancer of 2.2 (1.0–4.6) (trend p=0.03) compared with non-drinkers.

Beverage type and colon cancer

There were no overall patterns of association of colon cancer with any beverage type, although there was a borderline significant trend (p=0.07) for decreasing risk associated with increasing wine consumption (table 3▶). In analyses of the effects of percentage of wine of total alcohol intake on colon cancer, no significant associations were found (data not shown). There were no differences in the results when we analysed proximal and distal colon cancers separately (data not shown).

Table 3 .

Relative risk of colon and rectal cancer according to weekly intake of beer, wine, and spirits in the present study from the Copenhagen Centre for Prospective Studies, Denmark 1976–1993

| Colon |

Rectum |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects (cases) | Relative risk* | 95% CL | Subjects (cases) | Relative risk* | 95% CL | |

| Beer (drinks/wk) | ||||||

| 0 | 5388 (62) | 1.0 | 5388 (21) | 1.0 | ||

| <1 | 6020 (126) | 1.1 | 0.8–1.5 | 6020 (46) | 0.9 | 0.6–1.4 |

| 1–6 | 9723 (118) | 1.0 | 0.8–1.3 | 9723 (57) | 1.2 | 0.8–1.8 |

| 7–13 | 3979 (41) | 0.7 | 0.4–1.2 | 3979 (46) | 1.8† | 1.1–2.9 |

| ≥14 | 4022 (64) | 1.2 | 0.8–1.7 | 4022 (32) | 1.4 | 0.8–2.4 |

| Trend: p=0.37 | Trend: p=0.33 | |||||

| Wine (drinks/wk) | ||||||

| 0 | 6450 (85) | 1.0 | 6450 (46) | 1.0 | ||

| <1 | 5518 (112) | 1.0 | 0.8–1.3 | 5518 (44) | 0.9 | 0.6–1.3 |

| 1–6 | 14438 (185) | 0.9 | 0.7–1.1 | 14438 (93) | 1.0 | 0.7–1.3 |

| 7–13 | 1682 (21) | 0.9 | 0.5–1.5 | 1682 (12) | 0.9 | 0.5–1.8 |

| ≥14 | 1044 (8) | 0.5 | 0.2–1.0 | 1044 (7) | 0.9 | 0.4–2.1 |

| Trend: p=0.07 | Trend: p=0.87 | |||||

| Spirits (drinks/wk) | ||||||

| 0 | 9301 (76) | 1.0 | 9301 (46) | 1.0 | ||

| <1 | 6792 (131) | 0.9 | 0.7–1.2 | 6792 (50) | 0.9 | 0.7–1.3 |

| 1–6 | 10997 (173) | 1.3† | 1.1–1.7 | 10997 (80) | 1.0 | 0.7–1.5 |

| 7–13 | 1358 (19) | 0.8 | 0.5–1.4 | 1358 (18) | 1.4 | 0.8–2.4 |

| ≥14 | 684 (12) | 1.0 | 0.5–1.9 | 684 (8) | 1.3 | 0.6–3.0 |

| Trend: p=0.72 | Trend: p=0.23 | |||||

*All adjusted for age, sex, smoking, body mass index, study of origin, and alcohol intake of the remaining two types of alcohol.

†p<0.05.

95% CL, 95% confidence limits.

Beverage type and rectal cancer

There was an increasing risk of rectal cancer with increasing amounts of beer and spirits, although the relationship was not significant (table 3▶). Drinkers of more than 14 drinks a week of beer and spirit had relative risks of 1.4 (0.8–2.4) and 1.3 (0.6–3.0) compared with non-drinkers of beer and spirits, respectively. There was no association or a slight decreased risk between wine intake and rectal cancer.

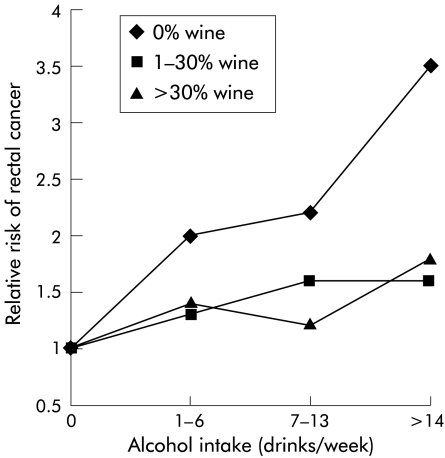

In evaluating beverage type as a percentage of total alcohol amount, subjects were categorised according to the percentage of wine of total alcohol intake and their total alcohol intake (table 4▶). The relative risks of rectal cancer in these categories are shown in fig 1▶. There was a higher relative risk among subjects who did not include wine in their alcohol intake compared with those who did include wine. Subjects drinking more than 14 drinks a week with more than 30% wine had a relative risk of 1.8 (1.0–3.2) compared with non-drinkers. Subjects drinking the same amount of alcohol, but including only beer and spirits, had a relative risk of 3.5 (1.8–6.9) compared with non-drinkers.

Table 4 .

Number of subjects (number of cases of colon cancer; rectal cancer) and mean (SD) alcohol intake, according to total alcohol and percentage of wine of total alcohol intake in the present study from the Copenhagen Centre for Prospective Studies, Denmark 1976–1993

| Percentage of wine of total alcohol intake |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% |

1–30% |

>30% |

||||

| Subjects (cases) | Mean alcohol | Subjects (cases) | Mean alcohol | Subjects (cases) | Mean alcohol | |

| Drinks per week | ||||||

| 0 | 5712 (96;28)* | 0.0 | ||||

| 1–6 | 1516 (14;11) | 3.2 (1.7) | 1812 (37; 14) | 4.1 (1.7) | 6394 (78; 35) | 3.4 (1.6) |

| 7–13 | 876 (13;9) | 9.4 (1.5) | 2394 (28; 21) | 9.5 (1.8) | 2726 (36; 13) | 10.1 (2.1) |

| ≥14 | 1198 (24;17) | 28.7 (17.6) | 3878 (58; 32) | 30.8 (19.8) | 2626 (27; 22) | 23.9 (12.4) |

*Non-drinkers=reference category.

Figure 1 .

Relative risk of rectal cancer, according to the percentage of wine of total alcohol intake, and according to total alcohol intake, in the present study from the Copenhagen Centre for Prospective Studies, Denmark 1976–1993. Relative risk is set at 1.0 among non-drinkers. Adjusted for age, sex, smoking, study of origin, and body mass index.

DISCUSSION

Our study supports an overall association between alcohol consumption and risk of rectal cancer, including a significant dose-response relationship between total alcohol intake and risk of rectal cancer. Furthermore, the data suggest an anticarcinogenic effect of wine, as the increased risk of rectal cancer was confined to drinkers not including wine in their alcohol intake compared with drinkers including wine. No association between alcohol and colon cancer was found.

Present study

The advantages of the present study include the fact that it was based on a large randomly sampled population with a long prospective follow up period, which insures a large number of end points and eliminates the chance of recall and selection bias. As it was a population based study, results are readily transferable to the general public. Subjects lost to follow up were kept to a minimum due to record linkage. Because of careful elimination of subjects with a history of cancer at baseline, previous cancer or cancer treatment were not allowed to influence the association between alcohol and colorectal cancer.

The study also had limitations. Misclassification of alcohol intake over time is possible due to the fact that categorisation is based on information obtained at baseline and does not take into account the possibility of changes in a subject’s alcohol consumption during follow up with regard to both amount and type. Traditionally, such a misclassification, assuming that it is influential, is considered to bias the estimates towards unity. However, in studies such as these with multiple categories, only misclassification between the most extreme categories would bias the estimates towards null, and misclassification between adjacent categories could bias the estimates in any direction.27

Furthermore, in this study it was not possible to exclude subjects with a higher predisposition to colorectal cancer than the general public due to hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer or familial adenomatous polyposis. In a report from the nationwide Danish Polyposis Register,28 it is estimated that familial adenomatous polyposis constitutes 0.07% of all Danish colorectal cancers. Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer is estimated to cause approximately 1–5% of all colorectal cancers.29 Thus genetic predisposition influences the aetiology of a limited number of colorectal cases and therefore failing to exclude these cases is an unlikely explanation for the relationship found between alcohol and rectal cancer.

The study was also limited by the risk of residual confounding due to the likely multifactorial aetiology of colorectal cancer. Several other relative risk factors for colorectal cancer have been identified through epidemiological studies; diet and micronutrients, including high intake of fat, meat, protein, low intake of fibre, low intake of folate and calcium, low physical activity, large body size, and smoking.1 Leisure time physical activity did not affect the association between alcohol and colorectal cancer in the present study and adjustment for body mass index and smoking was carefully made. There is a possibility of residual confounding from lack of adjustment for dietary factors in this study as the Copenhagen Centre for Prospective Population Studies does not have any information on diet. However, several case control studies found that adjusting for dietary factors such as fibre, fat, and protein intake did not change the results concerning alcohol and colorectal cancer.29–33 A dietary factor would also have to be strongly associated with both rectal cancer and alcohol consumption to explain the association found in this study.34 Wine drinkers in this study were reported to be more physically active and have a higher level of education than non-wine drinkers. However, neither physical activity nor educational level proved to have any influence as a confounder in the development of rectal cancer. Socioeconomic factors other than educational level may influence the relation between wine drinking and rectal cancer and the possibility of residual confounding exists.

Other studies

Our study confirms the findings of Goldbohm and colleagues10 who found a dose-response relationship between alcohol and rectal cancer and no association between alcohol and colon cancer in a large follow up study of the general public in the Netherlands, including 478 colorectal cases. Several other studies support the association between alcohol and rectal cancer,5,30,31,35–37 while others found no association between alcohol and rectal cancer.8,9,32 The lack of an association between alcohol and colon cancer, including colon subsites, in the present study is in contrast with the findings of studies which reported a significant dose-response between alcohol and colon cancer.6,7,35,37,38 Of seven studies5,10,30,31,35–37 confirming an association between alcohol and rectal cancer, six showed an increased risk with beer intake, three studies showed an increased risk with spirits intake, two studies showed an increased risk with wine intake, while one study showed no association between wine and rectal cancer.

To our knowledge no other study has evaluated the effects of percentage of wine of total alcohol intake on colorectal cancer. In the present study the observed reduced risk suggests an anticarcinogenic effect of wine compared with other beverages types, which is supported by two of the largest case control studies conducted so far. A study in Northern Italy in 199239 with a total of 1470 histologically confirmed colorectal cases found no association between alcohol and colon and rectal cancer, with wine being the preferred beverage. Likewise, another study from Italy,40 including 1953 histologically confirmed colorectal cases, observed no association between alcohol and colorectal cancer.

The diverse findings of these prospective studies is striking and probably relates to the differences in so many aspects of these studies. For example, the range of alcohol intake differed markedly among the studies. Studies with a small range may not have been able to find an association even if one exists. Two cohort studies with the highest alcohol category of >10 drinks a month11 and >4 g alcohol a week9 failed to show any significant association between alcohol and colorectal cancer. Some studies used mortality as an end point instead of morbidity, which may introduce differences in results considering the advances made in cancer treatment over the past decades. The reference groups differed between studies also; some used abstainers while others used the lowest alcohol category as the reference. It is not clear if differences in the reference category account for some of the observed diversity but it is possible that abstainers differ markedly in many aspects of life compared with drinkers. Finally, there were marked differences in factors considered as confounders and adjusted for accordingly, which may indicate residual confounding as an explanation for the diversity in results. The case control studies were very heterogeneous. Case control studies have the disadvantage of a considerable risk of recall and selection bias. Furthermore, a review by Kune and Vitetta in 199241 showed a significant difference in results between studies using hospital and community controls, probably related to bias introduced by the use of hospital controls who in all likelihood drink more than the general public. The lack of consistency in confounder adjustment is also true for case control studies.

Biological mechanisms

A number of hypotheses concerning the carcinogenic effects of alcohol on the large bowel have been proposed. To our knowledge, research so far has not distinguished between colon and rectal cancer as most research has been performed on human colon cancer cells. Experimental research offers no explanation as to why several studies, including ours, found an increased risk of rectal cancer associated with alcohol consumption but no association with colon cancer. In a study by Simanovski and colleagues,42 rectal mucosal hyperproliferation was found in rectal biopsies from chronic alcoholics compared with rectal biopsies from controls. Rectal mucosal hyperproliferation is associated with an increased cancer risk.

Several hypotheses on the role of alcohol in colorectal carcinogenesis provide theories that may be applicable to rectal cancer. Contamination of alcoholic beverages with carcinogens has been suggested, as past production proceedings in breweries has been known to contaminate beer with the carcinogen nitrosamine.7 The fairly consistent finding of an association between beer alone and colorectal cancer supports this theory. Another theory is that alcohol consumption, through its damaging effect on the liver, inhibits the detoxification of carcinogens, including nitrosamine.43 Generation of carcinogenic metabolites has also been suggested as a biological explanation for the observed carcinogenic effect of alcohol. Acetaldehyde, a metabolite of alcohol and a known animal carcinogen, has been implicated in colorectal carcinogenesis because low aldehyde dehydrogense activity in the colonic mucosa causes accumulation of acetaldehyde in the colon.44 In a study of Japanese alcoholics, an increased odds ratio for colon cancer was observed among those alcoholics with a mutant aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 allele.45 Reduced intake and bioavailability of essential micronutrients, including folate and methionine, is another hypothesis. Methylation of DNA, which may be of significance in gene regulation, is dependent on intake of folate and methionine. Alcohol combined with a low methionine low folate diet has been shown to increase the risk of colon cancer in men.4

The observed anticarcinogenic effect of wine in the present study is supported by experimental research on components of wine. Resveratrol, a phytoalexin found in grapes and wine, has been shown to inhibit cellular events associated with tumour initiation, promotion, and progression.46 With regard to colorectal cancer, resveratrol has been shown to depress the growth of colorectal aberrant crypt foci in rats47 and to inhibit growth of human colon cancer cells.15 Methanol extracts from red and white wine containing flavonoids, especially anthocyanin, suppressed the growth of human cancer colon cells.14

CONCLUSION

In summary, the present study provides evidence of a causal relationship between alcohol and rectal cancer. The carcinogenic effect of alcohol on rectal cancer appears to be reduced when wine is included in alcohol intake. This suggests an anticarcinogenic effect of wine, consistent with the findings of experimental studies.

Abbreviations

ICD, International Classification of Diseases

REFERENCES

- 1.Potter J. Nutrition and colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control 1996;7:127–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longnecker M, Orza M, Adams M, et al. A metaanalysis of alcoholic beverage in relation to risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control 1990;1:59–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kearney J, Giovannucci E, Rimm E. Diet, alcohol, and smoking and the occurrence of hyperplastic polyps of the colon and rectum (United States). Cancer Causes Control 1995;6:45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kono S, Ikeda N, Yanai F, et al. Alcoholic beverages and adenomatous polyps of the sigmoid colon: A study of male self-defence officials in Japan. Int J Epidemiol 1990;19:848–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stemmermann G, Nomura A, Chyou P, et al. Prospective study of alcohol intake and large bowel cancer. Dig Dis Sci 1990;11:1414–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Acherio A, et al. Alcohol, low-methionine-low-folate diets, and risk of colon cancer in men. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87:265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glynn S, Albanes D, Pietinen P, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of colorectal cancer in a cohort of Finnish men. Cancer Causes Control 1996;7:214–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adami H-O, MCLaughlin JK, Hsing AW, et al. Alcoholism and cancer risk: A population-based cohort study. Cancer Causes Control 1992;3:419–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gapstur S, Potter J, Folsom A. Alcohol consumption and colon and rectal cancer in postmenopausal women. Int J Epidemiol 1994;23:50–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldbohm R, Van den Brandt P, Veer P, et al. Prospective study on alcohol consumption and the risk of cancer of the colon and rectum in the Netherlands. Cancer Causes Control 1994;5:95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsing AW, McLaughlin JK, Chow WH, et al. Risk factors for colorectal cancer in a prospective study among U.S. white men. Int J Cancer 1998;77:549–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grønbæk M, Becker U, Johansen D, et al. Population based cohort study of the association between alcohol intake and cancer of the upper digestive tract. BMJ 1998;317:844–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prescott E, Grønbaek M, Becker U, et al. Alcohol intake and risk of lung cancer. Influence of type of alcoholic beverage. Am J Epidemiol 1999;149:463–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamei H, Hashimoto Y, Tatsurou K, et al. Anti-tumor effect of methanol extracts from red and white wines. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 1998;6:447–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider Y, Vincent F, Duraton B, et al. Anti-proliferative effect of resveratrol, a natural component of grapes and wine, on human colonic cells. Cancer Lett 2000;158:85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Appleyard M, Hansen AT, Schnohr P, et al. Østerbroundesøgelsen. The Copenhagen City Heart Study. A book of tables with data from the first examination (1976–1978) and a five year follow-up (1981–1983). The Copenhagen City Heart Study Group. Scand J Soc Med Suppl 1989;41:1–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hein HO, Sørensen H, Suadicani P, et al. Alcohol consumption, Lewis phenotypes, and the risk of ischaemic heart disease. Lancet 1993;341:392–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heitmann BL. The influence of fatness, weight change, slimming history and other life style variables on diet reporting in Danish man and women aged 35–65 years. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1993;17:329–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organisation. International Classification of Diseases: Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 1955.

- 20.World Health Organisation. International Classification of Diseases: Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 1989.

- 21.World Health Organisation. International Classification of Diseases: Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 1965.

- 22.The National Board of Health. The Activity in the Hospitals of Denmark 1979. Copenhagen, Denmark: Statistics (in Danish), 1981.

- 23.Storm HH, Michelsen EV, Clemmensen ICH, et al. The Danish Cancer Registry—history, content quality and use. Dan Med Bull 1997;44:535–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Storm HH. Completeness of cancer registration in Denmark 1943–1966 and efficiacy of record linkage procedures. Int J Epidemiol 1988;17:44–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kjaergaard J, Clemmensen IH, Storm HH. Validity and completeness of registration of surgically treated malignant gynaecological diseases in the Danish National Hospital Registry. J Epidemiol Biostat 2001;6:387–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen AR, Overgaard J, Storm HH. Validity of breast cancer in the Danish Cancer Registry. A study based on clinical records from one county in Denmark. Eur J Cancer Prev 2002;11:359–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johansen C, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Skotte J, et al. Validation of job-exposure matrix for assessment of utility worker exposure to magnetic fields. Appl Occup Environ Hyg 2002;17:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bülow S, Faurschou Nielsen T, Bülow C, et al. The incidence rate of familial adenomatous polyposis. Results from the Danish Polyposis Register. Int J Colorect Disc 1996;11:88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aaltonen LA, Salovaara R, Kristo P. Incidence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and the feasibility of molecular screening for the disease. N Engl J Med 1998;338:1481–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freudenheim JL, Graham S, Marshall JR, et al. Lifetime alcohol intake and risk of rectal cancer in western New York. Nutr Cancer 1990;13:101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newcomb P, Storer B, Marcus P. Cancer of the large bowel in women in relation to alcohol consumption: a case-control study in Wisconsin (United States). Cancer Causes Control 1993;4:405–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riboli E, Cornée J, Macquart-Moulin G, et al. Cancer and polyps of the colorectum and lifetime consumption of beer and other alcoholic beverages. Am J Epidemiol 1991;134:157–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kune S, Kune GA, Watson LF. Case-control study of alcoholic beverages as etiologic factors: The Melbourne Colorectal Cancer Study. Nutr Cancer 1987;9:43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grønbæk M, Sørensen TIA. Is the effect of wine on health confounded by diet? Epidemiology 2002;13:236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirayama T. Association between alcohol and cancer of the sigmoid colon: Observations from a Japanese cohort study. Lancet 1989;23:725–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klatsky A, Armstrong M, Friedman G, et al. The relations of alcoholic beverage use to colon and rectum cancer. Am J Epidemiol 1988;5:1007–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Longnecker MP. A case-control study of alcoholic beverage consumption in relation to risk of cancer of the right colon and rectum in men. Cancer Causes Control 1990;1:5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyer F, White E. Alcohol and nutrients in relation to colon cancer in middle-aged adults. Am J Epidemiol 1993;138:225–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barra S, Negri E, Franceschi S, et al. Alcohol and colorectal cancer: a case-control study from Northern Italy. Cancer Causes Control 1992;3:153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tavani A, Ferraroni M, Mezzetti M, et al. Alcohol intake and risk of cancers of the colon and rectum. Nutr Cancer 1998;30:213–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kune GA, Vitetta L. Alcohol consumption and the etiology of colorectal cancer: A review of the scientific evidence from 1957 to 1991. Nutr Cancer 1992;18:97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simanowski UA, Haman N, Knuhl M, et al. Increased rectal cell proliferation following alcohol abuse. Gut 2001;49:418–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hakkak R, Korourian S, Ronis M, et al. Effects of diet and ethanol on the expression and localization of cytochromes P450 2E1 and P450 2C7 in the colon of male rats. Biochem Pharm 1996;51:61–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salaspuro M. Bacterocolonic pathway for ethanol oxidation: Characteristic and implications. Ann Med 1996;28:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yokoyama A, Marumatsu T, Ohmori T, et al. Alcohol-related cancers and aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 in Japanese alcoholics. Carcinogenesis 1998;8:1383–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jang M, Cai L, Udeani GO, et al. Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes. Science 1997;275:218–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tessitore L, Davit A, Sarotto I, et al. Resveratrol depresses the growth of colorectal aberrant crypt foci by affecting bax and p21(CIP) expression. Carcinogenesis 2000;21:1619–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]