Abstract

Background: There is no direct evidence for an animal model of Helicobacter pylori induced duodenal ulcer.

Aim: In this study we evaluated the roles of bacterial strain and age of experimental animals in induction of duodenitis and duodenal ulcer in Mongolian gerbils after H pylori infection.

Methods: Specific pathogen free Mongolian gerbils were inoculated orally with three bacterial strains (H pylori ATCC 43504, TN2GF4, and K-6, a clinical isolate from a patient with gastric cancer in our clinic). These strains have both the cagA gene and VacA. Five week old gerbils were used to emulate prematurity infection and 14 week old animals were used as mature test subjects. Animals were observed for 12 weeks after inoculation. Interleukin 8 (IL-8) production in gastric epithelial cells (MKN74) after coculture with the H pylori strains was measured by ELISA.

Results: Gastritis and gastric ulcers were found in all gerbils infected with the three strains. However, duodenitis and gastric metaplasia were seen more frequently in gerbils infected with TN2GF4 and K-6 strains than in the ATCC 43504 infected or control groups (p<0.05). Superficial duodenal ulcers with severe duodenitis and gastric metaplasia were found in two gerbils inoculated at 14 weeks with the TN2GF4 strain but none at five weeks. The TN2GF4 strain stimulated significantly higher levels of IL-8 than ATCC 43504 and K6 strains (p=0.0039).

Conclusions: When injected into adult Mongolian gerbils, a specific strain (TN2GF4) of H pylori can induce duodenitis with gastric metaplasia and superficial duodenal ulcers. Induction of duodenal ulcer in an animal model fulfills the requirements of Koch’s postulates for establishing a role for H pylori as a causative agent.

Keywords: duodenal ulcer, Mongolian gerbils, Helicobacter pylori, duodenitis, duodenal ulcer

Helicobacter pylori infection causes duodenal ulcers, most gastric ulcers,1 and adenocarcinoma2 in humans. Experimental models of H pylori infection have been described using gnotobiotic piglets,3 euthymic germ free mice,4 athymic nude mice,5 and monkeys.6 The Mongolian gerbil also appears to be an appropriate animal model of H pylori infection.7–9 Gastrointestinal diseases such as gastritis, gastric ulcer, and adenocarcinoma that mimic human H pylori infection can be studied in the Mongolian gerbil model. However, there is no direct evidence that H pylori infection actually induces duodenal ulcers in this animal model. The effects of variables such as strain differences in H pylori infection and age of the experimental animal have not been investigated.

In this study, we infected both immature and mature Mongolian gerbils with three H pylori strains. Our goal was to study the role of both bacterial strain and subject age on evolution of duodenal ulcers after infection with H pylori.

METHODS

Bacterial strains

The bacterial strains used in this study were H pylori ATCC 43504 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Virginia, USA), TN2GF4 (a gift from Takeda Chemical Industries, Ltd, Osaka, Japan), and K-6, which was isolated from a patient with gastric cancer in our clinic. These strains have both the cagA gene and vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) that was verified by polymerase chain reaction methods10 and cytotoxin assay.11 The bacteria were cultured under microaerophilic conditions at 37°C for four days on blood agar. Subsequent culture was for 24 hours in Brucella broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Michigan, USA) with 10% horse serum.

Animals

Specific pathogen free male Mongolian gerbils (bred in the Animal Research Center, Tokyo Medical and Dental University) were infected at five and 14 weeks of age. Specific pathogen free implies that the gerbils are not infected and free of Sendai virus, mouse hepatitis virus, Mycoplasma pulmonis, Clostridium piliforme, Dermatophytes, Citrobacter rodentium, Pasteurella pneumotropica, Corynebacterium kutscheri, Pseudomonas aerginosa, Salmonella spp, Staphylococcus aureus, Mycoplasma pulmonis, Giardia muris, Spironucleus muris, Syphacia spp, Helicobacter spp, and Aspicularis tetrapttera. Three to five animals were housed per cage and given free access to both a commercial rodent diet (CE-2; Clea Japan, Tokyo, Japan) and sterile water. Animals that had been fasting for 24 hours were given, via a feeding needle, a single intragastric dose of 1 ml of a 1×108 colony forming units (CFU)/ml suspension of H pylori. Control animals received Brucella broth alone.

Histopathology and culture

Both experimentally infected and control gerbils were sacrificed by cervical dislocation under anaesthesia 12 weeks after inoculation. The stomachs were opened along the greater curvature, beginning at the gastro-oesophageal junction and ending at the proximal portion of the duodenum, and any gastroduodenal lesions were observed macroscopically. Half of the specimen was stapled onto paper and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histological examination by routine methods. Fixed tissue was cut into longitudinal strips for examination of the gastroduodenal mucosa. Paraffin embedded sections were cut and stained with haematoxylin-eosin, Giemsa, and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS).

The remaining half of the specimen was homogenised with Brucella broth, diluted, and inoculated onto a modified Skirrow’s agar. Cultures were incubated at 37°C for seven days under microaerobic conditions. Infection was quantified by counting colonies per plate and expressed as log CFU per gastroduodenal wall.

The thickness of pyloric-type mucosa was measured at five randomly selected points of the foveolar epithelium zone in the middle antrum on haematoxylin-eosin stained slides obtained from the stomach of each gerbil. Because the inflammatory component of the mucosa was virtually identical to that found in human H pylori gastritis, the degree of activity, inflammation, atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia was graded according to the updated Sydney system.12 The presence of H pylori was diagnosed histologically in specimens stained with Giemsa. The proximal duodenum was confirmed by identifying the pyloric ring and Brunner’s gland. Gastric metaplasia was defined as the occurrence of foci of gastric epithelial cells containing apical PAS positive neutral mucin together with the absence of a brush border. All pathological analyses were performed in a blinded fashion by one pathologist (IO).

Serology

Blood samples were obtained from anaesthetised animals by cardiac puncture at the time of sacrifice. Serum IgG antibody to H pylori was measured by an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; HM-CAP, EPI, New York, USA). An ELISA system developed at Seac Yoshitomi Ltd (Fukuoka, Japan) was used to quantitate anti-H pylori IgG of Mongolian gerbils using peroxidase conjugated antimouse immunoglobulins (Dako Japan, Tokyo, Japan) as the secondary antibody. Optical density (OD)450 was measured spectrophotometrically (Emax; Japan Molecular Device Co., Hyogo, Japan). A cut off value of 0.1 OD was indicative of serological evidence of H pylori infection (Ikeda, personal communication).

Stimulation of interleukin 8 (IL-8) secretion in gastric epithelial cell line

H pylori strains were harvested in a modified Skirrow agar containing 10% horse blood for seven days at 37°C under microaerobic conditions. After collection of colonies with a disposable plastic loop, they were suspended at 1×107 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, Missouri, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma) and used immediately.

MKN74 human gastric epithelial cell line (JCRB0255; Health Science Research Resources Bank, Osaka, Japan) was maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS. For quantification of IL-8, MKN74 cell monolayers in 24 well plates were cocultured with or without H pylori strains for five hours in triplicate. Supernatants were then removed from the wells, centrifuged at 15 000 g, and stored at −70°C until assayed for IL-8 protein by ELISA (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All procedures were done in duplicate.

Statistical analyses

The Kruskal-Wallis test and Mann-Whitney U test were used for statistical comparison of bacterial counts, IgG titres to H pylori, histological scores of both the stomach and duodenum, and IL-8 production in MKN74 cells between the experimental groups. Fisher’s exact test was used to test differences in infection rates of H pylori and the occurrence rates of gastric and duodenal ulcers. STAT VIEW software, version J 5.0 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA), was used for all analyses. Differences with p<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Infection rate

Colonisation with H pylori was determined by culture, histology, or IgG titres (table 1▶). The bacterium was considered to be infectious if at least two of three tests (bacteriological culture, histological results, serology) were positive. The histological results were consistent with positive serum IgG titres (OD >0.1). IgG titres of gerbils infected with strain K-6 at five weeks of age were lower than those of gerbils infected with strain TN2GF4 at 14 weeks of age and ATCC 43504 at five weeks of age (p=0.045 and 0.047). Eighteen of 27 inoculated gerbils were positive for both culture and IgG antibody. Eight of the inoculated gerbils were positive for IgG antibody but negative for culture. The remaining gerbil, inoculated with the H pylori strain K-6 at five weeks of age, was negative for culture, histology, and IgG titres. It is likely that failure of H pylori inoculation occurred in this gerbil who was excluded from the histopathological examination. The infection rate was similar (80–100%) in both age groups and in groups of animals infected with the three different bacterial strains. Control groups showed no evidence of H pylori infection.

Table 1 .

Characteristics of Helicobacter pylori infection with bacterial strains ATCC-43504, TN2GF4, and K-6 in Mongolian gerbils

| Mongolian gerbils infected at 14 weeks of age |

Mongolian gerbils infected at 5 weeks of age |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | ATCC 43504 (n=3) | TN2GF4 (n=6) | K-6 (n=4) | Control (n=4) | p Value* | ATCC 43504 (n=5) | TN2GF4 (n=4) | K-6 (n=5) | Control (n=6) | p Value* |

| Bacterial counts† | 5.2 (0.3) | 5.0 (0.7) | 5.7 (1.2) | N.D. | 0.174 | 5.7 (1.2) | 4.8 (0.2) | 4.4 (0.10) | ND | 0.071 |

| Culture positive | 2/3 | 5/6 | 2/4 | 0/4 | 3/5 | 3/4 | 3/5 | 0/6 | ||

| Histological results | 3/3 | 6/6 | 4/4 | 0/4 | 0.017 | 5/5 | 4/4 | 4/5 | 0/6 | 0.025 |

| IgG titres (OD450) | ||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.37 (0.12) | 0.46 (0.32) | 0.17 (0.15) | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.017 | 0.44 (0.37) | 0.33 (0.31) | 0.16 (0.20) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.025 |

| Response (>0.1) | 3/3 | 6/6 | 4/4 | 0/4 | 5/5 | 4/4 | 4/5 | 0/6 | ||

| Infection rate (%) | 100‡ | 100‡ | 100‡ | 0 | 100‡ | 100‡ | 80‡ | 0 | ||

*The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparisons between the four groups.

†Bacterial counts were expressed as log10 colony forming units (CFU)/gastric wall (mean (SD)).

‡p<0.05 for a bacterial strain group compared with uninfected controls (Fisher’s exact test).

OD, optical density.

Macroscopic and histopathological findings

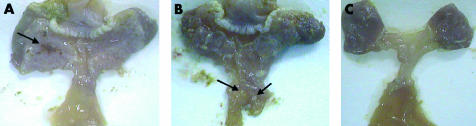

The antral mucosa of all infected gerbils was expanded and thickened with abundant mucus (fig 1A▶). Gastric ulcer lesions were seen at the antrum (pyloric-type mucosa) in all infected gerbils (fig 1A▶). The duodenal mucosa of most infected gerbils in TN2GF4 and K-6 groups showed thickened and erosive lesions (fig 1B▶). Control animals had normal gastric and duodenal mucosa (fig 1C▶).

Figure 1 .

(A) The antrum of an infected gerbil, 12 weeks after inoculation with the bacterial strain Helicobacter pylori TN2GF4, showed expanded and thickened mucosa with abundant mucus. Gastric ulcer lesions can be seen at the antrum (pyloric-type mucosa, arrow). (B) The duodenum of an infected gerbil in the TN2GF4 group showed thickened mucosa and two superficial ulcers (arrows). (C) The gastric and duodenal mucosa of a non-infected gerbil in the control group showed no visible changes.

Histopathological findings from sections of the stomach are shown in tables 2 and 3▶▶. Neutrophil activity and chronic inflammation, characterised by dense neutrophil and mononuclear cell infiltration, and lymphoid follicle formation in both the mucosa and submucosa were observed in the fundic region of gerbils infected at 14 weeks of age (p=0.008 and 0.009) and in the pyloric region in both age groups (14 weeks: p=0.016 and 0.011; five weeks: p=0.003 and 0.007). In the fundic region of gerbils infected at five weeks of age, neutrophil activity and chronic inflammation were milder and observed less frequently than in animals infected at 14 weeks. In the fundic region of gerbils infected with strain TN2GF4 at 14 weeks of age, neutrophil activity and chronic inflammation were higher than that of strain ATCC at five weeks of age, and highest among the infected gerbils. Mucosal thickness in the pyloric region of infected animals in both age groups was significantly increased compared with controls (p=0.008, 0.007), and the thickness of infected gerbils with strain TN2GF4 at 14 weeks of age was higher than that of strain K-6 at five weeks of age, and highest among the infected gerbils.

Table 2 .

Histological lesions in the stomach and duodenum of Mongolian gerbils infected with Helicobacter pylori strains ATCC-43504, TN2GF4, and K-6

| Mongolian gerbils infected at 14 weeks of age |

Mongolian gerbils infected at 5 weeks of age |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | ATCC 43504 (n=3) | TN2GF4 (n=6) | K-6 (n=4) | Control (n=4) | ATCC 43504 (n=5) | TN2GF4 (n=4) | K-6 (n=4) | Control (n=6) |

| Fundic-type mucosa | ||||||||

| Gastric ulcer | 0/3 (0%) | 0/6 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/6 (0%) |

| Pyloric-type mucosa | ||||||||

| Gastric ulcer | 3/3 (100%)* | 6/6 (100%)* | 4/4 (100%)* | 0/4 (0%) | 5/5 (100%)* | 4/4 (100%)* | 4/4 (100%)* | 0/6 (0%) |

| Superficial ulcer | 2/3 (67%) | 3/6 (50%) | 2/4 (50%) | 0/4 (0%) | 5/5 (100%) | 2/4 (50%) | 3/4 (75%) | 0/6 (0%) |

| Duodenal mucosa | ||||||||

| Duodenitis | 1/3 (33%) | 6/6 (100%)* | 4/4 (100%)* | 0/4 (0%) | 1/5 (20%) | 4/4 (100%)* | 4/4 (100%)* | 0/6 (0%) |

| Gastric metaplasia | 0/3 (0%) | 6/6 (100%)* | 3/4 (75%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 4/4 (100%)* | 2/4 (50%) | 0/6 (0%) |

| Superficial ulcer | 0/3 (0%) | 2/6 (33%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/6 (0%) |

*p<0.05 for a bacterial strain group compared with uninfected controls (Fisher’s exact test).

Table 3 .

Histological scores in the stomach and duodenum of Mongolian gerbils infected with Helicobacter pylori strains ATCC-43504, TN2GF4, and K-6

| Score |

p Value† |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mongolian gerbils infected at 14 weeks of age |

Mongolian gerbils infected at 5 weeks of age |

||||||||||

| Bacteria strain group | Mean | Median | Range* | ATCC | TN2GF4 | K-6 | Control | ATCC | TN2GF4 | K-6 | Control |

| ATCC 43504-14W (n=3) | |||||||||||

| Fundic activity | 0.667 | 1 | 0, 1 | 0.157 | >0.2 | 0.074 | >0.2 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.033 | |

| Fundic inflammation | 0.667 | 1 | 0, 1 | 0.123 | >0.2 | 0.074 | >0.2 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.033 | |

| Pyloric activity | 2.67 | 3 | 2, 3 | 0.371 | >0.2 | 0.018 | >0.2 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.006 | |

| Pyloric inflammation | 2.33 | 2 | 2, 3 | 0.157 | >0.2 | 0.018 | 0.049 | 0.074 | >0.2 | 0.006 | |

| Pyloric mucosal thickness (μM) | 473 | 490 | 420, 510 | 0.052 | >0.2 | 0.032 | 0.099 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.020 | |

| Duodenal activity | 0.333 | 0 | 0, 1 | 0.033 | 0.076 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.074 | 0.074 | 0.157 | |

| Duodenal inflammation | 0.333 | 0 | 0, 1 | 0.027 | 0.076 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.074 | 0.074 | 0.157 | |

| TN2GF4-14W (n=6) | |||||||||||

| Fundic activity | 1.17 | 1 | 1, 1 | 0.157 | >0.2 | 0.005 | 0.032 | 0.171 | 0.065 | 0.001 | |

| Fundic inflammation | 1.33 | 1 | 1, 2 | 0.123 | >0.2 | 0.006 | 0.026 | 0.114 | 0.053 | 0.002 | |

| Pyloric activity | 2.33 | 2 | 2, 3 | 0.371 | >0.2 | 0.006 | >0.2 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.002 | |

| Pyloric inflammation | 2.83 | 3 | 2.5, 3 | 0.157 | >0.2 | 0.005 | >0.2 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.001 | |

| Pyloric mucosal thickness (μM) | 633 | 630 | 550, 725 | 0.052 | 0.068 | 0.010 | 0.169 | >0.2 | 0.033 | 0.004 | |

| Duodenal activity | 2.00 | 2 | 1, 3 | 0.033 | 0.165 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.002 | |

| Duodenal inflammation | 2.33 | 3 | 1, 3 | 0.027 | 0.099 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.046 | 0.046 | 0.002 | |

| K-6-14W (n=4) | |||||||||||

| Fundic activity | 1.00 | 1 | 1, 1 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.008 | 0.074 | >0.2 | 0.127 | 0.003 | |

| Fundic inflammation | 1.00 | 1 | 1, 1 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.008 | 0.074 | >0.2 | 0.127 | 0.003 | |

| Pyloric activity | 2.50 | 2.5 | 2, 3 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.013 | >0.2 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.004 | |

| Pyloric inflammation | 2.50 | 2.5 | 2, 3 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.013 | 0.091 | 0.127 | >0.2 | 0.004 | |

| Pyloric mucosal thickness (μM) | 458 | 410 | 395, 520 | >0.2 | 0.068 | 0.019 | 0.138 | 0.147 | >0.2 | 0.010 | |

| Duodenal activity | 1.25 | 1 | 1, 2 | 0.076 | 0.165 | 0.011 | 0.023 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.003 | |

| Duodenal inflammation | 1.25 | 1 | 1, 2 | 0.076 | 0.099 | 0.011 | 0.023 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.003 | |

| Control-14W (n=4) | |||||||||||

| Fundic activity | 0.000 | 0 | 0, 0 | 0.074 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.176 | 0.040 | 0.127 | >0.2 | |

| Fundic inflammation | 0.000 | 0 | 0, 0 | 0.074 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.176 | 0.040 | 0.127 | >0.2 | |

| Pyloric activity | 0.000 | 0 | 0, 0 | 0.018 | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.011 | >0.2 | |

| Pyloric inflammation | 0.000 | 0 | 0, 0 | 0.018 | 0.005 | 0.013 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.011 | >0.2 | |

| Pyloric mucosal thickness (μM) | 178 | 180 | 150, 200 | 0.032 | 0.010 | 0.019 | 0.014 | 0.020 | 0.020 | >0.2 | |

| Duodenal activity | 0.000 | 0 | 0, 0 | >0.2 | 0.008 | 0.011 | >0.2 | 0.008 | 0.008 | >0.2 | |

| Duodenal inflammation | 0.000 | 0 | 0, 0 | >0.2 | 0.006 | 0.011 | >0.2 | 0.008 | 0.008 | >0.2 | |

| ATCC 43504-5W (n=5) | |||||||||||

| Fundic activity | 0.400 | 0 | 0, 1 | >0.2 | 0.032 | 0.074 | 0.176 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.103 | |

| Fundic inflammation | 0.400 | 0 | 0, 1 | >0.2 | 0.026 | 0.074 | 0.176 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.103 | |

| Pyloric activity | 2.40 | 2 | 2, 3 | >0.2 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.009 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.003 | |

| Pyloric inflammation | 3.00 | 3 | 3, 3 | 0.049 | >0.2 | 0.091 | 0.005 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.002 | |

| Pyloric mucosal thickness (μM) | 558 | 550 | 550, 600 | 0.099 | 0.169 | 0.138 | 0.014 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.006 | |

| Duodenal activity | 0.200 | 0 | 0, 0.5 | >0.2 | 0.008 | 0.023 | >0.2 | 0.024 | 0.024 | >0.2 | |

| Duodenal inflammation | 0.200 | 0 | 0, 0.5 | >0.2 | 0.007 | 0.023 | >0.2 | 0.024 | 0.024 | >0.2 | |

| TN2GF4-5W (n = 4) | |||||||||||

| Fundic activity | 0.750 | 1 | 0, 1 | >0.2 | 0.171 | >0.2 | 0.040 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.016 | |

| Fundic inflammation | 0.750 | 1 | 0, 1 | >0.2 | 0.114 | >0.2 | 0.040 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.016 | |

| Pyloric activity | 2.25 | 2 | 2, 2 | >0.2 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.011 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.003 | |

| Pyloric inflammation | 3.00 | 3 | 3, 3 | 0.074 | >0.2 | 0.127 | 0.008 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.003 | |

| Pyloric mucosal thickness (μM) | 568 | 505 | 480, 780 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.147 | 0.020 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.010 | |

| Duodenal activity | 1.00 | 1 | 1, 1 | 0.074 | 0.053 | >0.2 | 0.008 | 0.024 | >0.2 | 0.003 | |

| Duodenal inflammation | 1.00 | 1 | 1, 1 | 0.074 | 0.046 | >0.2 | 0.008 | 0.024 | >0.2 | 0.003 | |

| K-6-5W (n = 4) | |||||||||||

| Fundic activity | 0.500 | 0.5 | 0, 1 | >0.2 | 0.065 | 0.127 | 0.127 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.066 | |

| Fundic inflammation | 0.500 | 0.5 | 0, 1 | >0.2 | 0.053 | 0.127 | 0.127 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.066 | |

| Pyloric activity | 2.25 | 2 | 2, 2 | >0.2 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.011 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.003 | |

| Pyloric inflammation | 2.75 | 3 | 3, 3 | >0.2 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.011 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.003 | |

| Pyloric mucosal thickness (μM) | 473 | 515 | 280, 580 | >0.2 | 0.033 | >0.2 | 0.020 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.010 | |

| Duodenal activity | 1.00 | 1 | 1, 1 | 0.074 | 0.053 | >0.2 | 0.008 | 0.024 | >0.2 | 0.003 | |

| Duodenal inflammation | 1.00 | 1 | 1, 1 | 0.074 | 0.046 | >0.2 | 0.008 | 0.024 | >0.2 | 0.003 | |

| Control-5W (n=6) | |||||||||||

| Fundic activity | 0.000 | 0 | 0, 0 | 0.033 | 0.001 | 0.003 | >0.2 | 0.103 | 0.016 | 0.066 | |

| Fundic inflammation | 0.000 | 0 | 0, 0 | 0.033 | 0.002 | 0.003 | >0.2 | 0.103 | 0.016 | 0.066 | |

| Pyloric activity | 0.000 | 0 | 0, 0 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.004 | >0.2 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | |

| Pyloric inflammation | 0.000 | 0 | 0, 0 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.004 | >0.2 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.003 | |

| Pyloric mucosal thickness (μM) | 172 | 175 | 140, 200 | 0.020 | 0.004 | 0.010 | >0.2 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.010 | |

| Duodenal activity | 0.000 | 0 | 0, 0 | 0.157 | 0.002 | 0.003 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.003 | 0.003 | |

| Duodenal inflammation | 0.000 | 0 | 0, 0 | 0.157 | 0.002 | 0.003 | >0.2 | >0.2 | 0.003 | 0.003 | |

*Numbers are 25th and 75th percentile score, respectively. †The Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison between scores and each other. 14W, 14 weeks; 5W, five weeks.

Gastric ulcers, limited to the mucosal propria (superficial ulcer) or extending to the muscular layer, were seen in the region of the pyloric-type mucosa of all infected gerbils but not in the fundic-type mucosa (table 2▶). In 17 of 26 infected animals (65%), gastric ulcers in the pyloric-type mucosa were found as superficial ulcers (erosions). Glandular atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, hyperplastic polyp, or adenocarcinoma was not observed in infected gerbils.

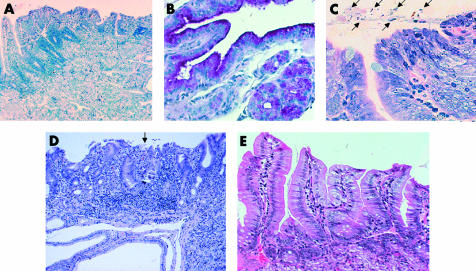

Histopathological findings from sections of the duodenum are shown in tables 2 and 3▶▶. Duodenitis characterised by dense neutrophil and mononuclear cell infiltration was seen more frequently in gerbils infected with strains TN2GF4 and K-6 (fig 2A▶) than in animals infected with ATCC 43504 or controls. In gerbils infected with strain TN2GF4 at 14 weeks of age, neutrophil activity was higher than that of strain ATCC 43504 at both ages and of controls, and chronic inflammation was highest among infected gerbils. In the duodenal region of gerbils infected at five weeks of age, neutrophil activity and chronic inflammation were milder than in animals infected at 14 weeks. Gastric metaplasia occurred most frequently in gerbils infected with strain TN2GF4 (100% v 0% in controls at both 14 and five weeks; p=0.0048 each) (fig 2B▶). In those gerbils infected with strain K-6, gastric metaplasia was found in 75% and 50% at 14 and five weeks versus 0% for controls. No gastric metaplasia was found in those gerbils infected with ATCC 43504 or controls. All of the mucus of the gastric metaplasia in the duodenum was colonised by H pylori (fig 2C▶). In two of six gerbils (33%) infected with TN2GF4 at 14 weeks of age, duodenal ulcers with severe duodenitis and gastric metaplasia were found (fig 2D▶). These duodenal ulcers were limited to the mucosal propria (superficial ulcer, erosion), located in the proximal portion of the duodenum. Neither neutrophil activity nor chronic inflammation was seen in the stomach or duodenum of control gerbils (fig 2E▶).

Figure 2 .

(A) Duodenitis characterised by dense neutrophil and mononuclear cell infiltration is seen in a gerbil infected with bacterial strain Helicobacter pylori K-6 (haematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×100). (B) The duodenal mucosa in a gerbil infected with bacterial strain H pylori TN2GF4 at 14 weeks was positive for periodic acid-Schiff staining, indicating gastric metaplasia (original magnification ×200). (C) The mucus of gastric metaplasia in the duodenum in an infected gerbil from the TN2GF4 group, inoculated at 14 weeks, was colonised by H pylori (arrows) (Giemsa, original magnification ×400). (D) Superficial duodenal ulcer (arrows) in the gastric metaplasia with severe duodenitis was evident in a gerbil from the TN2GF4 group, inoculated at 14 weeks. Brunner’s glands can be seen beneath the gastric metaplasia (haematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×100). (E) No duodenitis is seen in a non-infected gerbil of the control group (haematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×200).

Stimulation of IL-8 secretion in gastric epithelial cell line

Comparing IL-8 production in MKN74 cells after coculture with the H pylori strains, strain TN2GF4 stimulated significantly higher levels of IL-8 (1538 (303) pg/ml) (fig 3▶) than strain ATCC 43504 (154 (24) pg/ml; p=0.0039), and K6 (175 (6) pg/ml; p=0.0039). IL-8 production by strains ATCC 43504 and K6 was significantly higher than controls (55 (8) pg/ml; p=0.0038 and 0.0039, respectively).

Figure 3 .

Interleukin 8 (IL-8) production in MKN74 cells after coculture with the three bacterial strains of Helicobacter pylori. **p<0.01 between H pylori strains, and between H pylori strains and controls (Mann-Whitney U test).

DISCUSSION

Many reports have documented H pylori infection in gerbils7–9,13–17 but the occurrence of duodenal ulcer is not a consistent feature of infection. Mild to moderate inflammation in the duodenum has been reported 12 and 24 weeks after infection with strain ATCC 43504 but no ulcerative lesions were found and the occurrence of gastric metaplasia was not described.13,14 In this study, we have reported the occurrence of duodenal ulcer in Mongolian gerbils infected with H pylori at 14 weeks of age. Duodenal ulcer was found only in two of six animals (33%) infected with TN2GF4 at 14 weeks and in none of the ATCC 43504 or K-6 groups. Moreover, no ulcer was found in animals infected at five weeks old, regardless of the strain. These results may explain why duodenal ulcer has not been observed in previous investigations13,14 which used the ATCC 43504 strain to infect gerbils with H pylori at 4–5 weeks old. For unknown reasons, animals in this age group and the ATCC 43504 strain do not appear to be suitable for induction of duodenal ulcers.

Histological detection of duodenal ulcer was concurrent with severe duodenitis and gastric metaplasia. Although duodenitis can be found in most TN2GF4 and K-6 inoculation groups (75–100%), it is rarely found in the ATCC 43504 inoculation group (infected at 14 weeks of age, 20%; five weeks, 33%). This result suggests that the strains TN2GF4 and K-6 may have an affinity for the duodenal mucosa. Gastric metaplasia was seen in all animals in the TN2GF4 inoculation group and moreover, duodenal ulcers occurred only in the TN2GF4 inoculation group. The finding of duodenal ulcer with gastric metaplasia in the gerbil model is similar to results in human duodenal ulcer. In human duodenal ulcer, the presence of gastric metaplasia in the duodenum is a major risk factor for duodenal ulcer disease in patients colonised by H pylori.18,19 Gastric metaplasia has been viewed as a protective adaptation in duodenal epithelium exposed to high acidity.20 However, a recent study using a 24 hour gastric pH meter indicated that gastric hyperacidity was not associated with duodenal gastric metaplasia.21 Unfortunately, measurement of gastric acid output in Mongolian gerbils was not available and therefore it is difficult to determine whether gastric metaplasia found in this study was due to high acid output. Nevertheless, development of duodenal ulcer seems to be strongly associated with duodenitis and antral gastritis as severe duodenitis with gastric metaplasia and thickened antral mucosa due to antral gastritis were found in gerbils infected with strain TN2GF4 at 14 weeks of age. It has been postulated that H pylori strains which possess the cagA gene and functional VacA are associated with an increased prevalence of duodenal ulcer.10,11 The three strains of H pylori used in the study had both the cagA gene and VacA, so there may be other strain determinants for inducing duodenal ulcers. In the present study, we assessed the functionality of the cag island in these three strains by analysing IL-8 induction in vitro. The TN2GF4 strain stimulated significantly higher levels of IL-8 than strains ATCC 43504 and K6. Similar findings were reported by Israel and colleagues22 who infected gerbils with two different H pylori isolates that were cagA+ and toxigenic, and found one of their strains induced much more severe inflammation than the other. Microarray analysis of the two strains showed that the less inflammatory strain had a mid region deletion in the cag island but it still had the cagA gene. This indicates that the presence of cagA per se does not always signify the presence of a complete and functional cag island.

Glandular atrophy and intestinal metaplasia were found in Mongolian gerbils, 26 weeks after H pylori inoculation.23 In our study however, we observed the infected animals for 12 weeks after inoculation and neither atrophy nor intestinal metaplasia in the stomach was found. Hansson et al reported that duodenal ulcer disease has a protective effect against the development of gastric cancer.24 As all duodenal ulcers in the present study were concomitant with gastric ulcers, this model is not useful for verifying this protective effect.

Some patients with gastric ulcers also have or have had duodenal ulcers, and the incidence of coexistent gastric and duodenal ulcers ranges from 7% to 64%.25 Recently, a case study reported that H pylori infection carried the strongest association with gastroduodenal ulcer compared with gastric ulcer in the gastric body and prepyloric region.26 In most instances it was thought that duodenal ulcer was the primary disease, with gastric ulcer occurring secondarily, but one study has indicated that gastric ulcer was the primary disease in some patients.27 In the present study, we found gastric ulcer to be the primary disease due to H pylori associated gastritis, and duodenal ulceration occurred infrequently at a relatively early phase, 12 weeks after H pylori infection. It may be the reason why duodenal ulcers were superficial and not frequent in our model. Nord et al reported that gastric antral ulcer, but not gastric body or duodenal ulcer, was found in a child less than three years old.28 They also showed that duodenal ulcer was first noted in a five year old child and became more common with increasing age. This may resemble our results where duodenal ulcers were found in two gerbils inoculated at 14 weeks with the TN2GF4 strain but none at five weeks.

It is known that H pylori infection occurs mostly in childhood and new infection in adults is rare.29 Epidemiological studies of H pylori by both serology and urea breath tests showed that infection was commonly acquired in childhood30–32 and the rate of acquisition in adulthood is very low.33,34 In this study, the infection rate of H pylori was high (100%) and similar in both immature and mature gerbils. In this respect, the Mongolian gerbil model cannot be compared with human H pylori infection.

In conclusion, gastritis, gastric ulcer, and adenocarcinoma that mimic human H pylori infection were induced by H pylori inoculation in the Mongolian gerbil. In addition, both duodenitis and duodenal ulcer were induced by H pylori infection in an age and strain dependent manner. This fulfills the requirements of Koch’s postulates for establishing a role for H pylori as a causative agent of duodenal ulcer and validates a model system for studying this disease. However, the occurrence rate of duodenal ulcer was not significant with respect to controls; larger numbers of animals are needed to determine its significance.

Abbreviations

VacA, vacuolating cytotoxin A

CFU, colony forming units

PAS, periodic acid-Schiff

ELISA, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

OD, optical density

IL-8, interleukin 8

FBS, fetal bovine serum

REFERENCES

- 1.NIH Consensus Development Panel on Helicobacter pylori in Peptic Ulcer Disease. J Am Med Assoc 1994;272:65–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med 2001;345:784–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krakowka S, Morgan DR, Kraff WG, et al. Establishment of gastric Campylobacter pylori infection in the neonatal gnotobiotic piglet. Infect Immun 1987;55:2789–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karita M, Li Q, Cantero D, et al. Establishment of a small animal model for human Helicobacter pylori infection using germ-free mouse. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:208–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsuda M, Karita M, Morshed MG, et al. A urease-negative mutant of Helicobacter pylori constructed by allelic exchange mutagenesis lacks the ability to colonize the nude mouse stomach. Infect Immun 1994;62:3586–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Euler AR, Zurenko GE, Moe JB, et al. Evaluation of two monkey species (Macaca mulatta and Macaca fascicularis) as possible models for human Helicobacter pylori disease. J Clin Microbiol 1990;28:2285–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirayama F, Takagi S, Kusuhara H, et al. Induction of gastric ulcer and intestinal metaplasia in Mongolian gerbils infected with Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol 1996;31:755–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumoto S, Washizuka Y, Matsumoto Y, et al. Induction of ulceration and severe gastritis in Mongolian gerbils by Helicobacter pylori infection. J Med Microbiol 1997;46:391–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe T, Tada M, Nagai H, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection induces gastric cancer in Mongolian gerbils. Gastroenterology 1998;115:642–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Covacci A, Censini S, Bugnoli M, et al. Molecular characterization of the 128-kDa immunodominant antigen of Helicobacter pylori associated with cytotoxicity and duodenal ulcer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993;90:5791–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Figura N, Guglielmetti P, Rossolini A, et al. Cytotoxin production by Campylobacter pylori strains isolated from patients with peptic ulcers and from patients with chronic gastritis only. J Clin Microbiol 1989;27:225–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, et al. Classification and grading of gastritis: the updated Sydney system. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:1161–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawada Y, Sashio H, Yamamoto N, et al. Pathologic changes in the glandular stomach and duodenum in an H. pylori-infected Mongolian gerbil model. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998;27(suppl 1):S141–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Honda S, Fujioka T, Tokieda M, et al. Gastric ulcer, atrophic gastritis, and intestinal metaplasia caused by Helicobacter pylori infection in Mongolian gerbils. Scand J Gastroenterol 1998;33:454–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirayama F, Takagi S, Iwao E, et al. Development of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and carcinoid due to long-term Helicobacter pylori colonization in Mongolian gerbils. J Gastroenterol 1999;34:450–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikeno T, Ota H, Sugiyama A, et al. Helicobacter pylori-induced chronic active gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and gastric ulcer in Mongolian gerbils. Am J Pathol 1999;154:951–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyazaki SM, Matsuda MG. Blood flow, acidity and atrophic changes of the gastric mucosa in Mongolian gerbils infected with Helicobacter pylori. Dig Endosc 2001;13:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gormally SM, Kierce BM, Daly LE, et al. Gastric metaplasia and duodenal ulcer disease in children infected by Helicobacter pylori. Gut 1996;38:513–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gisbert JP, Blanco M, Cruzado AI, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection, gastric mucosa in the duodenum and the relationship with ulcer recurrence. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;12:1295–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patrick WJA, Denham D, Forrest APM. Mucosa change in the human duodenum: a light and electron microscopic study and correlation with disease and gastric acid secretion. Gut 1974;15:767–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savarino V, Sandoro Mela G, Zentilin P, et al. 24-hour gastric pH and extent of duodenal gastric metaplasia in Helicobacter pylori-positive patients. Gastroenterology 1997;113:741–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Israel DA, Salama N, Arnold CN, et al. Helicobacter pylori strain-specific differences in genetic content, identified by microarray, influence host inflammatory responses. J Clin Invest 2001;107:611–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe T, Tada M, Nagai H, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection induces gastric cancer in Mongolian gerbils. Gastroenterology 1998;115:642–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansson LE, Nyren O, Hsing AW, et al. The risk of stomach cancer in patients with gastric or duodenal ulcer disease. N Engl J Med 1996;335:242–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richardson CT. Gastric ulcer. In: Sleisenger MH, Fordtran JS eds. Gastrointestinal Disease, vol1. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company, 1983:675.

- 26.Chen MH, Wu MS, Lee WC, et al. A multiple logistic regression analysis of risk factors in different subtypes of gastric ulcer. Hepatogastroenterology 2002;49:589–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonnevie O. Gastric and duodenal ulcers in the same patient. Scand J Gastroenterol 1975;10:657–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nord KS, Rossi TM, Lebenthal E. Peptic ulcer in children: the predominance of gastric ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol 1981;75:153–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cave DR. How is Helicobacter pylori transmitted? Gastroenterology 1997;113(suppl 1):S9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein PD, Gilman RH, Leon-Barua R, et al. The epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in Peruvian children between 6 and 30 months of age. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:2196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell HM, Li YY, Hu PJ, et al. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in southern China: identification of early childhood as the critical period for acquisition. J Infect Dis 1992;166:149–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Granstrom M, Tindberg Y, Blennow M. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in a cohort of children monitored from 6 months to 11 years of age. J Clin Microbiol 1997;35:468–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faecett J, Shaw J, Cockburn M, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in a birth cohort of 21 years old New Zealanders. Gut 1997;39:A85 (abstract). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Cullen DJ, Collins BJ, Christiansen KJ, et al. When is Helicobacter pylori infection acquired? Gut 1993;34:1681–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]