Abstract

Background: Intestinal inflammation in Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) is characterised by an influx of neutrophils into the intestinal mucosa. S100A12 is a calcium binding protein with proinflammatory properties. It is secreted by activated neutrophils and interacts with the multiligand receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). Promising anti-inflammatory effects of blocking agents for RAGE have been reported in murine models of colitis.

Aims: To investigate expression and serum concentrations of S100A12 in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Methods: We performed immunohistochemical studies and immunofluorescence microscopy in biopsies from patients with CD and UC. S100A12 serum concentrations were analysed using a sandwich ELISA.

Results: Immunohistochemical studies revealed profound expression of S100A12 in inflamed intestinal tissue from IBD patients whereas no expression was found in tissue from healthy controls. Staining for S100A12 during chronic active CD and UC was restricted to infiltrating neutrophils. Serum S100A12 levels were significantly elevated in patients with active CD (470 (125) ng/ml; p<0.001, n=30) as well as those with active UC (400 (120) ng/ml; p<0.01, n=15) compared with healthy controls (75 (15) ng/ml; n=30). Even in inactive disease, elevated serum concentrations were found, at least in CD. S100A12 levels were well correlated with disease activity in CD and UC.

Conclusions: We demonstrated that neutrophil derived S100A12 is strongly upregulated during chronic active IBD, suggesting an important role during the pathogenesis of IBD. Serum S100A12 may serve as a useful marker for disease activity in patients with IBD.

Keywords: S100A12, EN-RAGE, calgranulin C, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis

The aetiology and pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is still poorly understood. Various hypotheses have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology, ranging from genetic alterations, dysregulated immune response against constituents of the normal gut flora, or unsuccessful elimination of unknown antigens.1 Despite obvious differences in initiating mechanisms, Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) share common immunological aberrations that constitute a status of ongoing inflammatory processes.2 One of the most prominent histological features observed in UC as well as in CD is infiltration of neutrophils into the inflamed mucosa at an early stage of inflammation.3,4 Disease activity in IBD is linked to an influx of neutrophils into the mucosa and subsequently into the intestinal lumen, resulting in the formation of so-called crypt abscesses. Neutrophil migration across intestinal epithelia induces transient opening of intercellular junctions but does not usually cause morphological discontinuities.5 One of the possible mediators that has been suggested to induce neutrophil infiltrate during the inflammatory process of IBD is epithelial derived interleukin 8.6,7 Activated neutrophils secrete a variety of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and thereby trigger infiltration of various inflammatory cells, including monocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, and granulocytes.8–11 One of the most important mediators during the inflammatory process of IBD is tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) which is expressed in the intestinal mucosa of patients with IBD.12,13 TNF-α triggers inflammation via an intracellular nuclear factor κB (NFκB) dependent signalling cascade. NFκB plays a key role in downstream processes in chronic inflammation, such as in IBD, by controlling transcription of proinflammatory cytokine genes.14,15

S100A12 (calgranulin C) is a member of the S100 family of calcium binding proteins specifically expressed by granulocytes.16 Extracellular S100A12 exhibits proinflammatory functions, including potent chemotactic activity, comparable with other chemotactic agents.17 Bovine S100A12 is a ligand for the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) which is found on macrophages, endothelium, and lymphocytes. Binding of S100A12 to RAGE mediates its proinflammatory properties.18 Intracellular signalling induces NFκB dependent secretion of different cytokines.19,20 The name EN-RAGE (for extracellular newly identified RAGE binding protein) has been introduced. Of particular interest is the fact that soluble (s)RAGE, the extracellular ligand binding domain of the receptor, has been proved to suppress inflammation in mouse models of chronic colitis.21 The most profound effect on inflammatory processes is achieved by combined treatment with blocking agents against RAGE and (s)RAGE. Recently, it has been shown that S100A12 is secreted by activated human neutrophils.22

As migration and infiltration of neutrophils into the inflamed tissue plays a pivotal role during the inflammatory process of IBD, we were interested in the role of S100A12 in IBD. The aim of the study was therefore to determine tissue expression and serum levels of S100A12 during chronic active IBD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients with IBD

We included 40 patients with CD and 34 patients with UC to correlate serum levels of S100A12 with overall disease activity. In parallel, C reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), white blood counts (WBC), and neutrophil counts were determined. Clinical disease activity in CD was documented using the Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI),23 and for UC using the colitis activity index (CAI), according to Rachmilewitz24 and the criteria of Truelove and Witts.25 Endoscopic and histological disease activity was documented (activity score 0–3; 0=no inflammation, 1=mild inflammation, 2=moderate inflammation, 3=severe inflammation). Patient data are summarised in table 1▶.

Table 1 .

Characteristics of patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

| Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| No of patients | 40 | 34 |

| Sex (F/M) | 28/12 | 10/24 |

| Age (y) (mean (range)) | 32 (18–56) | 33 (19–60) |

| Disease activity* | ||

| Active | 30 | 15 |

| Inactive | 10 | 19 |

| Localisation | ||

| Proctitis | 2 | |

| Distal colitis | 5 | |

| Left sided colitis | 8 | |

| Total colitis | 12 | |

| Medication | ||

| Steroids | 23 | 21 |

| 5-ASA or sulphasalazine | 36 | 33 |

| Azathioprine | 8 | 8 |

| Infliximab | 3 | 0 |

| No treatment | 0 | 1 |

*Assessment of disease activity using Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) in Crohn’s disease and colitis activity index (CAI) in ulcerative colitis. Active disease was defined as CDAI >150 or CAI ≥4.

In addition, 10 of our patients (six with CD and four with UC) were followed up over a period of eight months (range 3–12) to determine correlation of S100A12 serum levels with individual courses of disease activity.

Patients with severe bacterial infections/sepsis

Fifteen patients (seven male, eight female; mean age 36 years (range 10–75)) with severe bacterial infections were included to analyse S100A12 serum concentrations in diseases with systemic neutrophil activation. Blood cultures were positive in 13 patients while the remainder had pneumonia and appendicitis, respectively. CRP and neutrophil counts were documented.

Estimation of normal S100A12 serum levels

We estimated normal levels of S100A12 in the serum of 30 healthy controls without signs of inflammation (14 male, 16 female; mean age 34 years (range 19–57)) who either underwent routine blood tests at the Münster University Hospital or volunteered in our laboratory. There were no significant differences in age or sex distribution between patients and controls.

Purification of S100A12 protein and antibodies

S100A12 was isolated from human granulocytes, and recombinant protein was produced as described in detail previously.16,26 Polyclonal affinity purified rabbit antisera against human S100A12 were prepared as reported previously.16 Monospecificity of rabbit antihuman S100A12 antibody was analysed by immunoreactivity against purified human and recombinant S100A12, and western blot analysis of lysates of granulocytes.

Determination of S100A12 concentrations by sandwich ELISA

Concentrations of S100A12 in the serum of patients and supernatant of in vitro experiments were determined by a double sandwich enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) system established in our laboratory. Flat bottom 96 well microtitre plates (Maxisorp; Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany) were coated at 50 μl/well with 10 μg/well of anti-S100A12 in 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer, pH 9.6, incubated for 16 hours at 4°C, washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.4 (wash buffer), and blocked with wash buffer containing 0.25% bovine serum albumin (block buffer) for one hour at 37°C. Plates were washed once with wash buffer, and 50 μl of samples in at least three dilutions using block buffer were added for two hours at room temperature. ELISA was calibrated with purified S100A12 in concentrations ranging from 0.016 to 125 ng/ml. After three washings, biotinylated rabbit anti human-S100A12 (10 μg/well) was added and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. Plates were washed and incubated with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1:5000 dilution; Pierce, Rockford, Illinois, USA) for 30 minutes at 37°C. After washing three times, plates were incubated with ABTS (2,2′-azinobis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulphonic acid); Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and H2O2 in 0.05 M citrate buffer, pH 4.0, for 20 minutes at room temperature. Absorbency at 405 nm was measured after 20 minutes with an ELISA reader (MRX microplate reader; Dynatech Laboratories, Denkendorf, Germany). The assay has a linear range between 0.5 and 20 ng/ml and a sensitivity of <0.5 ng/ml. The inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation were <9% (n=10) and 8% (n=10), respectively.

Immunohistochemical studies

Paraffin embedded and frozen sections of bowel biopsies from patients with either active CD or active UC, and controls without intestinal inflammation were used to detect S100A12 expression by rabbit anti-S100A12 antibody. Disease activity was determined in haematoxylin and eosin stained sections. Monoclonal mouse antihuman granulocyte associated antigen CD15 antibody (Dako, Hamburg, Germany), a sensitive neutrophil marker, was used to detect neutrophils in infiltrates. Staining on serial sections was performed to detect coexpression of S100A12 and CD15 in infiltrates. For controls, monoclonal mouse IgM (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) and polyclonal rabbit IgG (Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany) of irrelevant specificity were employed. Secondary antibodies and substrates for colour reaction were used as described previously.26,27

Immunofluorescence microscopy

For double labelling experiments on bowel sections, anti-S100A12 antibody was followed by anti-CD15 antibody. We used affinity purified goat antimouse or goat antirabbit secondary antibodies conjugated with either Texas Red or FITC (Dianova). Fluorescence was analysed using a Zeiss Axioskop connected to an Axiocam camera supply with software Axiovision 3.0 for windows (Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany). No cross reactivity or spillover was detected in control experiments after omitting specific antibodies or replacing them by isotype matched control antibodies of irrelevant specificity.

Neutrophil preparation and stimulation

Human mixed donor granulocytes were isolated from buffy coats (German red cross, Münster, Germany) as described previously.16 Briefly, centrifugation through Ficoll-Hypague (Biocoll; Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) was performed to separate granulocytes from mononuclear cells and platelets. Erythrocytes were separated by dextran sedimentation. The remaining cells were washed twice in PBS. Purity of cells was above 95%, as determined by morphological analysis of Trypan blue stained cells. Granulocytes were resuspended at a final concentration of 1×107 cells/ml in serum free RPMI medium (Biochrom) supplemented with 1% glutamine, 1% non-essential amino acids, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Secretion was immediately induced by addition of TNF-α (recombinant human TNF-α; Cell Biology Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) to a final concentration of either 2 or 5 ng/ml. Stimulated and non-stimulated cells were incubated for 15 or 30 minutes at 37°C, respectively. Finally, granulocytes were pelleted at 500 g for five minutes at 4°C and the supernatant was saved for analyses of S100A12 with sandwich ELISA. Phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride was added at a final concentration of 1 mM to prevent proteolytic degradation. Cell lysis was assessed by analysing activity of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) using its capacity to convert NADH to NAD+ and measuring the decrease in absorbency of NADH at 340 nm.

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney U test was performed to determine significant differences in S100A12 and CRP expression between distinct categories. Correlation of serum markers with disease activity was analysed using Pearson’s test with software SPSS version 9.0 for Windows. Data are expressed as mean (95% confidence intervals). A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Immunohistochemistry/immunofluorescence

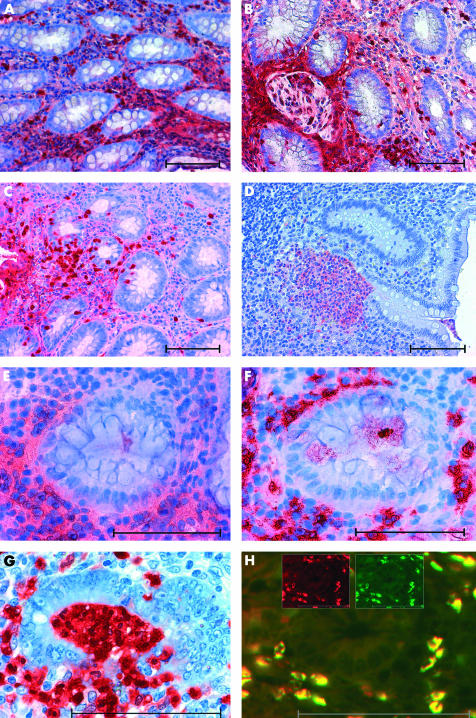

Immunohistochemical studies on tissues from patients with IBD showed a specific pattern of S100A12 expression by infiltrating cells in inflamed areas whereas no staining was found in tissues from patients with inactive disease. In addition, S100A12 was found in an extracellular distribution surrounding S100A12 positive cells, reflecting secretion of S100A12 and possibly binding to other RAGE bearing cells in infiltrates. In tissues from patients with active CD, S100A12 was detected around granulomatous lesions (fig 1A▶, B). In UC, crypt abscesses consisted of mainly S100A12 positive cells (fig 1D▶). Cells that transmigrated through the epithelium into the lumen also appeared to be S100A12 positive in CD as well as in UC. Costaining with monoclonal anti-CD15 provided evidence that expression of S100A12 was restricted to granulocytes that infiltrated inflamed tissue (fig 1▶).

Figure 1 .

Expression of S100A12 in tissues from patients with active Crohn’s disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC). Immunohistochemical staining showed extensive expression of S100A12 in inflamed colonic tissue of patients with active CD (A). S100A12 positive cells surrounded granulomatous lesions in CD (B). Similar local expression of S100A12 was found in UC (C). Numerous S100A12 positive cells assembled in crypt abscesses in UC (D). Staining of serial sections revealed colocalisation of S100A12 positive cells (E) and CD15 positive cells (F). In destructive crypt abscesses, S100A12 positive neutrophils transmigrated through the epithelium into the lumen (G). Immunofluorescence microscopy of double labelling studies with a-S100A12 Texas Red (red) and a-CD15-FITC (green) clearly proved expression of S100A12 by infiltrating CD15 positive granulocytes (H). Double labelled cells appear yellow due to summation of colours. The inserted figures in (H) show emission at a single wavelength for both fluorochromes. Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

Serum analysis

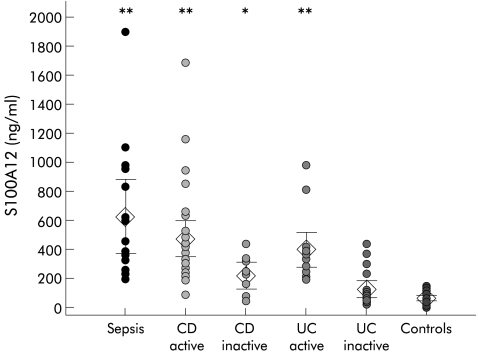

S100A12 serum levels from patients with active CD (CDAI >150, n=30) were significantly elevated compared with healthy controls (470 (125) ng/ml v 75 (15) ng/ml; p<0.001). There was also a significant difference between S100A12 serum levels in patients with active CD compared with inactive disease (470 (125) ng/ml v 215 (95) ng/ml; p<0.01). Even patients with inactive disease had serum levels that differed significantly from healthy controls (215 (95) ng/ml v 75 (15) ng/ml; p<0.05). Patients with active UC as determined by CAI ≥4 (n=15) had serum S100A12 levels that were also significantly elevated compared with healthy controls (400 (120) ng/ml v 75 (15) ng/ml; p<0.001). The difference between S100A12 serum levels in active and inactive UC (400 (120) ng/ml v 115 (55) ng/ml; p<0.001) was more pronounced than in CD. In contrast with CD, patients with inactive UC had serum levels comparable with those of healthy controls. Our data did not indicate any direct impact of steroid treatment on S100A12 serum levels (data not shown). Patients with severe bacterial infections had a mean S100A12 serum concentration of 630 (255) ng/ml. Data are summarised in fig 2▶.

Figure 2 .

Serum levels of S100A12 in bacterial infection, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and healthy controls. S100A12 levels were determined in 15 patients with severe bacterial infections, 40 patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), 34 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), and 30 healthy controls. Symbols show individual serum levels; diamonds indicate mean values with 95% confidence intervals (error bars). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, mean differences from healthy controls. Patients with active IBD had S100A12 serum levels comparable with patients with severe bacterial infections/sepsis.

CRP levels were higher in patients with active CD compared with inactive disease (2.0 (1.0) ng/ml v 0.3 (0.3) ng/ml; p<0.05). There was no significant difference between CRP levels of patients with active UC compared with patients with inactive disease (1.1 (0.9) mg/dl v 0.4 (0.3) mg/dl). ESR was significantly higher in patients with active CD (22 (7) mm/h v 9 (4) mm/h; p<0.01). However, ESR did not differ significantly between groups of UC patients (10 (5) mm/h v 12 (5) mm/h). We could further demonstrate that S100A12 serum levels strongly correlated with clinical disease activity in CD as well as in UC (table 2▶). Interestingly, only in CD was there a correlation with CRP and ESR whereas no correlation for these markers with disease activity was found in UC. The questionable accuracy of these classical markers in IBD is in accordance with previous reports.28,29 Endoscopic and histologic activity were determined simultaneously with S100A12 serum levels in 12 patients. Although this group was relatively small, there was a strong correlation between S100A12 serum concentrations and both endoscopic (r=0.72; p<0.01) and histological (r=0.83; p<0.001) scores. Patients with severe bacterial infections had extensive signs of systemic responses with a mean CRP of 18.3 (7.0) mg/dl, WBC 16 350 (3560)/μl, and high neutrophil counts (mean 12 140 (3110)/μl) in the periphery. Mean neutrophil count was only 7390 (1180)/μl in IBD (WBC 8300 (810)/μl), without showing a significant correlation with S100A12 concentrations (r=0.33; n=27, p=0.09). In contrast with patients with sepsis, S100A12 in the serum of IBD patients was therefore likely derived from neutrophils at the site of local mucosal inflammation.

Table 2 .

Correlation of serum S100A12, C reactive protein (CRP), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) with disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease

| S100A12 | CRP | ESR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDAI in CD | r=0.52 (n=40) | r=0.44 (n=25) | r=0.32 (n=28) |

| p | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.05 |

| CAI in UC | r=0.70 (n=34) | r=0.35 (n=26) | r=−0.1 (n=25) |

| p | <0.001 | NS | NS |

CD, Crohn’s disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; CDAI, Crohn’s disease activity index; CAI, colitis activity index.

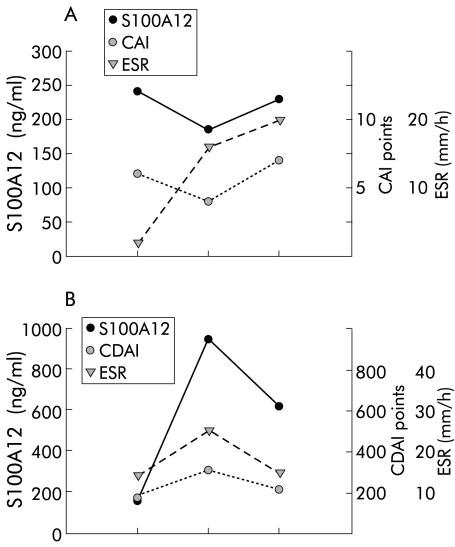

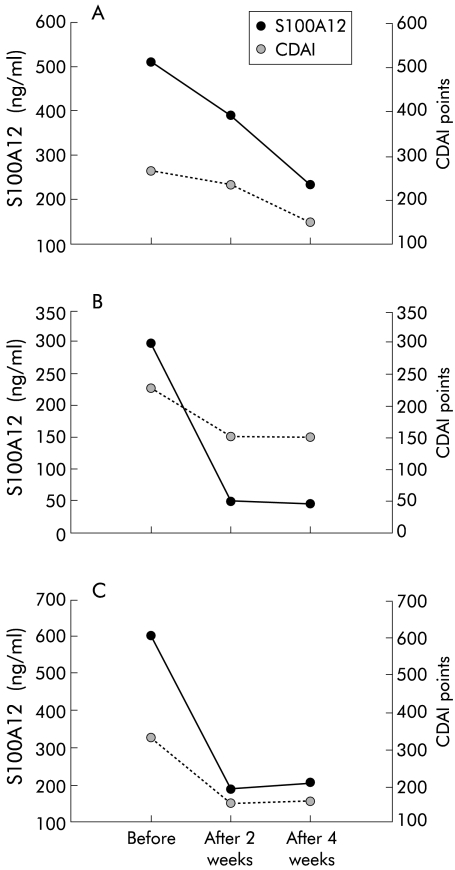

Individual follow up data of S100A12 serum levels in 10 patients with IBD confirmed a strong correlation with disease activity. In patients with UC, individual follow up data showed that S100A12 levels correlated better with disease activity than established markers of inflammation such as ESR (fig 3▶). S100A12 serum levels decreased rapidly after treatment with infliximab (fig 4▶).

Figure 3 .

Individual follow up of S100A12 serum levels, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and clinical disease activity. Individual courses of S100A12, ESR, and colitis activity index (CAI)/Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) in a patient with ulcerative colitis (UC) (A) and Crohn’s disease (CD) (B). Data are representative of 10 patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Figure 4 .

Changes in S100A12 serum levels in Crohn’s disease (CD) patients after infliximab treatment. Individual courses of S100A12 and Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) in three patients before, two weeks, and four weeks after treatment with infliximab.

S100A12 is secreted by activated neutrophils

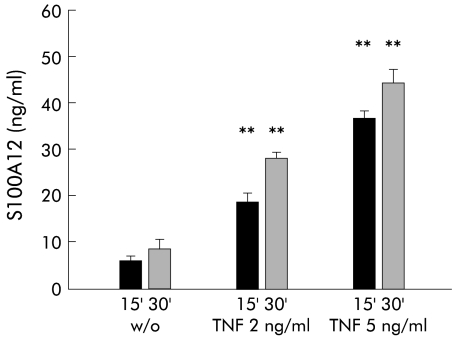

To demonstrate that S100A12 is indeed actively secreted by peripheral neutrophils, we isolated polymorphonuclear granulocytes by density gradient centrifugation and stimulated them with TNF-α. Minimal basal secretion of S100A12 was determined in unstimulated neutrophils. Concentrations of S100A12 in the supernatant of cells were 5–10 ng/ml in three independent experiments. There was a time and dose dependent increase in S100A12 secretion after stimulation with TNF-α (fig 5▶). There were no differences in viability and cell lysis between our experiments, as tested by LDH activity (data not shown).

Figure 5 .

S100A12 in the supernatant of neutrophils after stimulation with tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α). S100A12 was determined in supernatants of cells left untreated (w/o) or stimulated with TNF-α 2 or 5 ng/ml for 15 (15′) and 30 (30′) minutes, respectively. There was a time and dose dependent increase in S100A12 levels after treatment with TNF-α (**p<0.01; n=3).

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrated that S100A12 not only promotes inflammation in colitis models in mice but also plays a predominant role in human chronic IBD. We showed that S100A12 was strongly expressed by neutrophils infiltrating inflamed bowel tissue in IBD. In addition, high circulating amounts of S100A12 were determined in the serum of patients with CD as well as in those with UC. There is evidence that S100A12 is secreted by activated neutrophils which are the most abundant cell type found in inflammatory lesions in IBD. The final composition of infiltrating cells in IBD is dependent on the present spectrum of chemotactic cytokines and expression of specific receptors on various different cell types.11 As S100A12 is strongly chemotactic for other phagocytes, infiltration of S100A12 positive polymorphonuclear cells may be an early step prior to invasion of other leucocytes. S100A12 is a promoting factor for stimulation of cells that express RAGE on their surface. Although the role of S100A12 has not yet been completely defined, there is evidence that it plays a pivotal role during inflammatory conditions. Ligation of RAGE by S100A12 activates NFκB18 and there are numerous reports on the crucial role of NFκB activity during intestinal inflammation and in particular in IBD.15,30–32 The role of NFκB in IBD is also emphasised by the fact that part of the antiphlogistic action of steroids may be due to inhibition of NFκB driven expression of cytokines.32 Mucosal levels of glucocorticoid receptors seem to be decreased in IBD patients, independent of treatment, and this may result in decreased protection against NFκB action in the intestinal mucosa in IBD.33 NFκB is also upregulated by TNF-α, which is found in high amounts in inflamed tissue of IBD patients.9,13 In contrast with S100A12, TNF-α is only detectable at a very low level in the serum of IBD patients.3,34,35 Nevertheless, treatment with the anti-TNF-α chimeric antibody infliximab effectively reduced inflammation in CD.36–38 One of the major mechanisms of action of infliximab in CD is to induce apoptosis in activated monocytes.39 Interestingly, infliximab treatment rapidly diminished S100A12 levels in our patients. It may therefore be speculated that apoptosis in neutrophils might be an additional effect of anti-TNF-α treatment. It is also conceivable that there is intensive cross talk between cells secreting TNF-α and S100A12, thus leading to an uncontrolled and perpetuated inflammation which is responsive to blockade of either of these proinflammatory proteins. Suppression of chronic colonic inflammation in mice by blockade of the S100A12/RAGE interaction was accompanied by reduced TNF-α in serum.18 To further prove the relationship between TNF-α and neutrophil derived S100A12 in our study, we demonstrated that TNF-α stimulated S100A12 secretion in peripheral neutrophils. As TNF-α is hardly detectable in serum and S100A12 is an extremely stable protein even at room temperature or after multiple thawing and freezing cycles, analysis of serum S100A12 may provide an excellent marker for evaluation of response to anti-TNF-α treatment.

CD and UC share a variety of common immunological features but there are also important differences. Although serum levels of S100A12 were higher in CD than in UC, correlation of S100A12 levels with disease activity indices was lower in CD than in UC. Even in patients with inactive CD, we found significantly elevated S100A12 serum levels compared with controls. In fact, only 4/40 patients with CD had levels which were comparable with 30 healthy controls. This observation may be explained by the more systemic nature of immunological disturbances in CD compared with UC. Even in inactive disease, a few neutrophils remain in the intestinal tissue which might be responsible for elevated serum levels in these patients. S100A12 may therefore be a very sensitive parameter of residual disease activity. As neutrophil influx is a very early event during the inflammatory process of IBD, S100A12 may also be a useful marker in determining relapse of IBD. However, whether in this context S100A12 is superior to other serological markers needs to be determined in further studies. It is also conceivable that CDAI scores may have been falsely low in our patients who were consequently regarded to be in remission, despite having residual disease activity. Brignola et al found altered laboratory parameters in 55% of patients with inactive disease according to CDAI scores.40 The sensitivity of conventional activity indices may well be lower than that of S100A12 levels. In our UC study population, S100A12 was a better marker of disease activity than CRP or ESR.

The highly significant elevation of the neutrophil derived protein S100A12 also underlines the important role of neutrophils during intestinal inflammation. Neutrophils belong to the very early effector cell population that infiltrate the mucosa and intestinal epithelial cells, thereby altering intestinal barrier function during IBD. Among the proteins that are secreted by activated neutrophils are a number of substances stored in granules and only a few cytoplasmatic proteins such as calgranulins, including S100A12.22 The human neutrophilic lipocalin (HNL/NGAL) which is localised in specific granules of neutrophils and probably also expressed by colon epithelial cells is a useful faecal marker for UC due to its overexpression in inflamed bowel tissue.41,42 However, serum concentrations of lipocalins do not correlate with disease activity.43 We do not know faecal concentrations of S100A12, but faecal S100A8 and S100A9 are meaningful markers of bowel inflammation.44 The close correlation of S100A12 but not HNL/NGAL serum concentrations with local inflammatory activity may be due to the fact that S100A12 is released early on adherence of neutrophils to endothelium18 while the content of specific granules is more likely to be secreted later when cells migrate through the tissue.45 Moreover, elevated circulating levels of serum S100A12 provide evidence that neutrophils not only play a role within the local mucosal immune system but are also important in systemic immune responses in IBD. In this context, it is worth noting that a substantial number of patients with IBD revealed S100A12 serum concentrations comparable with those detected during sepsis. In contrast with IBD, parameters of systemic inflammation were significantly elevated in the presence of severe bacterial infections. The weak correlation of S100A12 with circulating neutrophils but strong correlation with endoscopic and histological findings in IBD indicate that local neutrophil driven inflammation is sufficient for systemic effects during chronic active IBD.

Taken together, our data demonstrated that S100A12 is a proinflammatory protein that plays a predominant role during intestinal inflammation in IBD. It is strongly expressed in inflamed tissue of patients with active CD and UC, and circulating levels of S100A12 seem to be reliable markers of inflammation in monitoring disease activity. Moreover, the beneficial effects of blocking agents in murine models of colitis make S100A12 an attractive target for novel therapeutic approaches in patients with IBD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karin Fischer and Eva Nattkemper for excellent technical assistance. The study was supported by grants of the “Interdisciplinary Centre of Clinical Research” (IZKF), University of Münster, Germany.

Abbreviations

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease

CD, Crohn’s disease

UC, ulcerative colitis

TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor α

NFκB, nuclear factor κB

RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end products

(s)RAGE, soluble RAGE

EN-RAGE, extracellular newly identified RAGE binding protein

CRP, C reactive protein

ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate

WBC, white blood count

CDAI, Crohn’s disease activity index

CAI, colitis activity index

ELISA, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

PBS, phosphate buffered saline

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase

REFERENCES

- 1.Sartor RB. Pathogenesis and immune mechanisms of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:5–11S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandtzaeg P, Haraldsen G, Rugtveit J. Immunopathology of human inflammatory bowel disease. Springer Semin Immunopathol 1997;18:555–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nikolaus S, Bauditz J, Gionchetti P, et al. Increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines by circulating polymorphonuclear neutrophils and regulation by interleukin 10 during intestinal inflammation. Gut 1998;42:470–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kucharzik T, Walsh SV, Chen J, et al. Neutrophil transmigration in inflammatory bowel disease is associated with differential expression of epithelial intercellular junction proteins. Am J Pathol 2001;159:2001–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nusrat A, Parkos CA, Liang TW, et al. Neutrophil migration across model intestinal epithelia: monolayer disruption and subsequent events in epithelial repair. Gastroenterology 1997;113:1489–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imada A, Ina K, Shimada M, et al. Coordinate upregulation of interleukin-8 and growth-related gene product-alpha is present in the colonic mucosa of inflammatory bowel. Scand J Gastroenterol 2001;36:854–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCormick BA, Hofman PM, Kim J, et al. Surface attachment of Salmonella typhimurium to intestinal epithelia imprints the subepithelial matrix with gradients chemotactic for neutrophils. J Cell Biol 1995;131:1599–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgio VL, Fais S, Boirivant M, et al. Peripheral monocyte and naive T-cell recruitment and activation in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 1995;109:1029–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reinecker HC, Steffen M, Witthoeft T, et al. Enhanced secretion of tumour necrosis factor-alpha, IL-6, and IL-1 beta by isolated lamina propria mononuclear cells from patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Clin Exp Immunol 1993;94:174–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazlam MZ, Hodgson HJ. Interrelations between interleukin-6, interleukin-1 beta, plasma C-reactive protein values, and in vitro C-reactive protein generation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 1994;35:77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacDermott RP, Sanderson IR, Reinecker HC. The central role of chemokines (chemotactic cytokines) in the immunopathogenesis of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 1998;4:54–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murch SH. Local and systemic effects of macrophage cytokines in intestinal inflammation. Nutrition 1998;14:780–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breese EJ, Michie CA, Nicholls SW, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-producing cells in the intestinal mucosa of children with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 1994;106:1455–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldwin AS Jr. The NF-kappa B and I kappa B proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu Rev Immunol 1996;14:649–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogler G, Brand K, Vogl D, et al. Nuclear factor kappaB is activated in macrophages and epithelial cells of inflamed intestinal mucosa. Gastroenterology 1998;115:357–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vogl T, Propper C, Hartmann M, et al. S100A12 is expressed exclusively by granulocytes and acts independently from MRP8 and MRP14. J Biol Chem 1999;274:25291–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Z, Tao T, Raftery MJ, et al. Proinflammatory properties of the human S100 protein S100A12. J Leukoc Biol 2001;69:986–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofmann MA, Drury S, Fu C, et al. RAGE mediates a novel proinflammatory axis: a central cell surface receptor for S100/calgranulin polypeptides. Cell 1999;97:889–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeh CH, Sturgis L, Haidacher J, et al. Requirement for p38 and p44/p42 mitogen-activated protein kinases in RAGE-mediated nuclear factor-kappaB transcriptional activation and cytokine secretion. Diabetes 2001;50:1495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lander HM, Tauras JM, Ogiste JS, et al. Activation of the receptor for advanced glycation end products triggers a p21(ras)-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway regulated by oxidant stress. J Biol Chem 1997;272:17810–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Yan SF, et al. The multiligand receptor RAGE as a progression factor amplifying immune and inflammatory responses. J Clin Invest 2001;108:949–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boussac M, Garin J. Calcium-dependent secretion in human neutrophils: a proteomic approach. Electrophoresis 2000;21:665–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, et al. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology 1976;70:439–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rachmilewitz D. Coated mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) versus sulphasalazine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. BMJ 1989;298:82–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis. Final report on a therapeutic trial. BMJ 1955;2:1041–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rammes A, Roth J, Goebeler M, et al. Myeloid-related protein (MRP) 8 and MRP14, calcium-binding proteins of the S100 family, are secreted by activated monocytes via a novel, tubulin-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 1997;272:9496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frosch M, Strey A, Vogl T, et al. Myeloid-related proteins 8 and 14 are specifically secreted during interaction of phagocytes and activated endothelium and are useful markers for monitoring disease activity in pauciarticular-onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:628–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen OH, Vainer B, Madsen SM, et al. Established and emerging biological activity markers of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:359–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niederau C, Backmerhoff F, Schumacher B. Inflammatory mediators and acute phase proteins in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Hepatogastroenterology 1997;44:90–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neurath MF, Pettersson S. Predominant role of NF-kappa B p65 in the pathogenesis of chronic intestinal inflammation. Immunobiology 1997;198:91–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neurath MF, Pettersson S, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH, et al. Local administration of antisense phosphorothioate oligonucleotides to the p65 subunit of NF-kappa B abrogates established experimental colitis in mice. Nat Med 1996;2:998–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schreiber S, Nikolaus S, Hampe J. Activation of nuclear factor kappa B inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 1998;42:477–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogler G, Meinel A, Lingauer A, et al. Glucocorticoid receptors are down-regulated in inflamed colonic mucosa but not in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Clin Invest 1999;29:330–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murch SH, Lamkin VA, Savage MO, et al. Serum concentrations of tumour necrosis factor alpha in childhood chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 1991;32:913–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Komatsu M, Kobayashi D, Saito K, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in serum of patients with inflammatory bowel disease as measured by a highly sensitive immuno-PCR. Clin Chem 2001;47:1297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rutgeerts P, D’Haens G, Targan S, et al. Efficacy and safety of retreatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody (infliximab) to maintain remission in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 1999;117:761–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB. Antitumor necrosis factor therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a review of agents, pharmacology, clinical results, and safety. Inflamm Bowel Dis 1999;5:119–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lugering A, Schmidt M, Lugering N, et al. Infliximab induces apoptosis in monocytes from patients with chronic active Crohn’s disease by using a caspase-dependent pathway. Gastroenterology 2001;121:1145–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brignola C, Lanfranchi GA, Campieri M, et al. Importance of laboratory parameters in the evaluation of Crohn’s disease activity. J Clin Gastroenterol 1986;8:245–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carlson M, Raab Y, Seveus L, et al. Human neutrophil lipocalin is a unique marker of neutrophil inflammation in ulcerative colitis and proctitis. Gut 2002;50:501–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nielsen BS, Borregaard N, Bundgaard JR, et al. Induction of NGAL synthesis in epithelial cells of human colorectal neoplasia and inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut 1996;38:414–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nielsen OH, Gionchetti P, Ainsworth M, et al. Rectal dialysate and fecal concentrations of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:2923–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tibble J, Teahon K, Thjodleifsson B, et al. A simple method for assessing intestinal inflammation in Crohn’s disease. Gut 2000;47:506–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borregaard N, Cowland JB. Granules of the human neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocyte. Blood 1997;89:3503–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]