Abstract

Background: The colonic epithelium maintains a life long reciprocally beneficial interaction with the colonic microbiota. Disruption is associated with mucosal injury.

Aims: We hypothesised that probiotics may limit epithelial damage induced by enteroinvasive pathogens, and promote restitution.

Methods: Human intestinal epithelial cell lines (HT29/cl.19A and Caco-2) were exposed to enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC 029:NM), and/or probiotics (Streptococcus thermophilus (ST), ATCC19258, and Lactobacillus acidophilus (LA), ATCC4356). Infected cells and controls were assessed for transepithelial resistance, chloride secretory responses, alterations in cytoskeletal and tight junctional proteins, and responses to epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulation.

Results: Exposure of cell monolayers to live ST/LA, but not to heat inactivated ST/LA, significantly limited adhesion, invasion, and physiological dysfunction induced by EIEC. Antibiotic killed ST/LA reduced adhesion somewhat but were less effective in limiting the consequences of EIEC invasion of cell monolayers. Furthermore, live ST/LA alone increased transepithelial resistance, contrasting markedly with the fall in resistance evoked by EIEC infection, which could also be blocked by live ST/LA. The effect of ST/LA on resistance was accompanied by maintenance (actin, ZO-1) or enhancement (actinin, occludin) of cytoskeletal and tight junctional protein phosphorylation. ST/LA had no effect on chloride secretion by themselves but reversed the increase in basal secretion evoked by EIEC. EIEC also reduced the ability of EGF to activate its receptor, which was reversed by ST/LA.

Conclusions: Live ST/LA interact with intestinal epithelial cells to protect them from the deleterious effect of EIEC via mechanisms that include, but are not limited to, interference with pathogen adhesion and invasion. Probiotics likely also enhance the barrier function of naïve epithelial cells not exposed to any pathogen.

Keywords: probiotics, enteroinvasive Escherichia coli, epidermal growth factor

The gastrointestinal tract harbours a complex and diverse ecosystem of microorganisms and the mechanisms by which gut immune and epithelial cells handle this constant antigenic stimulation are only beginning to be understood.1–3 Several lines of evidence have underscored the importance of a continuous cross talk between host and microbes in priming and maintaining a reciprocally beneficial relationship at various mucosal surfaces of the body. Many studies have also shown adverse consequences for the host if the normal equilibrium is disrupted.1–4

Probiotics are defined as “living organisms, which upon ingestion in certain numbers, exert health benefits beyond inherent basic nutrition”.4 The importance of a “healthy” gut microbiota has been recognised for a long time but only recently has specific attention been focused on the potential of probiotics as preventative and therapeutic agents in gastrointestinal diseases. The use of probiotics in animal models of inflammatory bowel disease and in diarrhoea of premature infants, severe burn patients, and acute and chronic colitis2,4,5 has shown potential beneficial effects of probiotic Escherichia coli strains, Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria, and Saccharomyces. However, the data in this area are relatively sparse and often controversial. Probiotics have been proposed to exert their beneficial effects by maintaining a normal intestinal milieu, by stimulating the immune system, by detoxifying colonic contents, by lowering serum cholesterol levels and promoting lactose tolerance, and by producing metabolites that are essential to maintain intestinal health.4–9 However, detailed mechanism based investigations of efficacy are largely lacking.

The intestinal epithelium, the site of interface with probiotics as well as other luminal constituents, conducts several functions required for intestinal homeostasis. Among these, the ability to form a barrier to oppose permeation of solutes into the lamina propria, and to regulate fluid and electrolyte transport, have been studied extensively. Alterations in both barrier and transport functions are common sequelae of a variety of digestive disorders, and may underlie diarrhoeal symptoms. Moreover, both transport and barrier functions, and epithelial turnover and differentiation, are known to be regulated in part by signal transduction events originating from the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFr).10 EGFr activation has been shown to cause redistribution of actin filaments in the apical zone of epithelia and to evoke changes in tight junctions and the cytoskeleton that are associated with an increase in transepithelial resistance (TER) and hence barrier function.10,11 Conversely, we and others have shown that infection of intestinal epithelial cell lines with invasive pathogens increases both basal and stimulated chloride secretion and decreases barrier function by rearranging cytoskeletal and tight junctional proteins.12–30

In this study, we hypothesised that pretreatment of epithelial cells with probiotics may protect them from the deleterious effects of subsequent infection with an enteroinvasive pathogen, and sustain recovery of the epithelium by promoting continued EGFr signalling. The aim of this study therefore was to investigate the effects of a combined preparation of two probiotic bacteria, Streptococcus thermophilus (ST) and Lactobacillus acidophilus (LA), on intestinal epithelial cell physiology. We hoped to provide a rationale for the use of probiotics as therapeutic and preventative agents, at least in infectious diarrhoea, and perhaps also in diseases associated with acute or chronic inflammation of the gut.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells

HT29/cl.19A and Caco-2 cells were cultured as previously described.12 Data obtained with both cell lines were qualitatively identical and have been used interchangeably in the results section. Briefly, cells were grown in McCoy’s medium (Cellgro; Fisher, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, and maintained in an atmosphere of 5% CO2-95% O2 at 37°C. Cells were used between passages 5 and 25, and grown in 75 cm2 flasks (Costar, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA), HA Millicell filter inserts (12 and 24 mm diameter; Millipore, Bedford, Massachusetts, USA), or glass chamber slides (Nalge Nunc, Rochester, New York, USA). Cells grown as polarised monolayers on filters reached confluency in 7–8 days and were used consistently within 14 days from seeding, or five days post confluency.

Bacteria

Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC O29:NM), non-invasive S thermophilus (ST, ATCC19258), and L acidophilus (LA, ATCC4356) were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, Maryland, USA). Trypticase soy broth (TSB; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA), supplemented as appropriate with 1% yeast extract (Sigma, St Louis, Missouri, USA), trypticase soy agar (TSA), or brain-heart infusion agar (Becton Dickinson, BBL, Sparks, Maryland, USA) with 5% sheep blood, or deMane-Rogosa-Sharpe broth (MRS) (Difco Labs., Detroit, Michigan, USA) were seeded with bacteria and incubated overnight at 37° C until the stationary phase was reached (table 1 ▶). ST and LA were routinely cultured under microaerophilic conditions. Subcultures of the overnight cultures in fresh medium were used to inoculate epithelial cell monolayers with bacteria in a phase of exponential growth.20

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in these studies

| Species | Strain No | Source | Gram stain | Growth conditions* |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus (LA) | 4356 | ATCC | Positive | MRS, 37° C |

| Streptococcus thermophilus (ST) | BAA-250 | ATCC | Positive | TSA-sb, 37° C, 5% CO2 |

| Enteroinvasive E coli (EIEC) | O29:NM | J Fierer UCSD | Negative | TSB-y, 37° C, 5% CO2 |

*See text for definition of abbreviations used.

Cell infection/treatment and intracellular survival assay

Confluent epithelial cell monolayers were treated with serum free medium containing exponentially grown bacteria at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50:1 to the apical surface. After one hour at 37°C, cells were washed and incubated in serum free medium with gentamicin (50 μg/ml) (for cells infected with invasive bacteria or uninfected controls) or in medium alone (for cells treated with probiotics) for one hour at 37°C. In control experiments, gentamicin had no effect on any of the parameters measured. Furthermore, no significant bacterial overgrowth was observed over the duration of the experiment under all conditions tested. In some experiments, cell monolayers were pretreated with ST/LA for one hour prior to infection with EIEC, as described above, and subsequent killing of extracellular bacteria with gentamicin. Some experiments were performed using probiotics that had either been killed with antibiotics (quinupristin/dalfopristin and vancomycin, 4 μg/ml, for one hour at 37°C) or heat inactivated (one hour at 100°C). Spent and filtered (0.2 μm), lyophilised, and concentrated (10×), supernatants from ST/LA cultures were also used in some experiments. Cells were then maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 in serum and antibiotic free medium. All treated monolayers had 50% of the culture medium changed every 24 hours after infection to avoid detrimental effects from nutrient utilisation and/or variations in pH. Cell invasion and bacterial survival were checked between three and 48 hours after infection to test the reproducibility of the infection protocol. Cell lysates and supernatants from treated monolayers and controls were checked by colony forming unit (CFU) counts on TSA or MRS agar (MRSA)

Adherence assay

Bacteria from log phase growth cultures were washed twice in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pelleted by centrifugation, and suspended at a concentration of 1×108 CFU/ml in cell growth medium. Bacterial suspension (1 ml) was diluted in 1 ml of cell growth medium and the suspension overlaid on cells grown on glass slides. The treated cells were then incubated at 37°C for 1–3 hours in an atmosphere of 5% CO2-95% O2. After incubation, cells were washed with PBS, fixed in absolute methanol, Gram stained, and observed by light microscopy. Adherence of EIEC was measured by counting Gram negative bacteria per 100 cells in 20 random microscopic fields.

Bacterial interference assay

Bacterial interference was quantified by a plate dilution method. Briefly, epithelial monolayers were exposed to ST/LA at 50:1 MOI for various times. Cells were then washed with warm PBS and exposed to EIEC (100:1 MOI) for one hour and subsequently tested for cell associated EIEC after hypotonic lysis using sterile distilled water supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin for 30 minutes on ice. Cell associated enteropathogens were defined as adherent plus intracellular bacteria and quantified by CFU counts of diluted cell lysates on TSB agar. To quantify only intracellular bacteria, parallel cell monolayers were exposed to serum free medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml gentamicin for one hour at 37°C after infection with EIEC, in the presence or absence of ST/LA pretreatment, then washed and lysed as described above. EIEC invasion was expressed as a percentage of intracellular bacteria compared with total cell associated bacteria. Probiotic interference was assessed by quantitating EIEC invasion in the presence and absence of probiotic pretreatment.

Electrophysiological studies

Infected and non-infected cell monolayers were tested for chloride secretion in modified Ussing chambers at various times after infection, as described previously.15,18,20 Mucosal and serosal baths contained Ringer’s solution (composition in mM: NaCl 115; NaHCO3 25; KH2PO4 0.4; K2HPO4 2.4; MgCl2 1.2; CaCl2 1.2; glucose 10; pH 7.4) which was gassed with 5% CO2-95% O2 and maintained at 37°C. The monolayers were continuously short circuited by application of short circuit current (Isc); open circuit potential difference was measured every 1–5 minutes and TER was calculated using Ohm’s law.

Electrical resistance across infected and control monolayers was also measured at various times using a “chopstick” voltohmeter (WPI, Sarasota, Florida, USA) with the inserts maintained at a constant temperature (37°C) and 5% CO2 gassing. Measurements were expressed in Ω×cm2 after subtracting mean values of resistance obtained from cell free inserts.

Permeability assay

Polarised cell monolayers were pretreated with probiotics for one hour, infected with EIEC as described above, and harvested after incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere for 12 hours. Fluorescein sulphonic acid (FS; Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon, USA; molecular weight 478 Da, 200 μg/ml) or fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran-10S (FITC-D10; Sigma; molecular weight 10 000, 20 mg/ml) was added to the basolateral side.31 Dishes were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for one hour with gentle mixing at 15 minute intervals. After the initial incubation, at 15 minute intervals up to two hours thereafter, the FS and FITC-D10 content of apical (Ap) and basolateral (Bl) samples was measured as fluorescence intensity of 1:250 dilutions in distilled water (492 nm excitation and 515 nm emission wavelengths). Monolayer permeability was expressed as FS or FITC-D10 clearance: [FS]Bl–[FS]Ap/[FS]Bl, corrected for insert area (nl/cm2/h). A standard curve using incremental concentrations of FS or FITC-D10 was constructed for each assay.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis

Infected and uninfected cells grown on 24 mm diameter Millicell HA filters were harvested at various times after infection and processed as previously described.32 Proteins of interest were immunoprecipitated by overnight incubation at 4°C on a mixer with an appropriate dilution of specific antibody (anti-ZO-1, antioccludin, and antiactinin from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, California, USA; antiphosphotyrosine, antiphosphoserine, anti-EGFr, and anti-ERK 1,2 from Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, Kentucky, USA) in cold lysis buffer32 supplemented with additional phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (20 μM). Samples were then incubated with protein A agarose at 4°C for one hour with constant mixing. After washing, the immunoprecipitated proteins were electrophoresed on 7.5% or 4.5–15% polyacrylamide gels (BioRad, Hercules, California, USA) and transferred onto blotting membranes (Polyscreen PVDF; NEN, Boston, Massachusetts, USA). After overnight blocking (PBS/Tween supplemented with 1% non-fat dry milk), blots were incubated with primary and secondary antibodies (horseradish peroxidase conjugated antimouse IgG, antirabbit IgG, or antiphosphotyrosine, as appropriate) for 60 minutes at room temperature. Proteins were visualised by chemiluminescence reagents (ECL Plus, Amersham, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA) and exposed to X-OMAT film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, New York, USA).

Chemicals

Unless otherwise indicated, all chemicals were of reagent grade and were obtained from Sigma.

Data analysis

All data are expressed as means (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed by repeated measures ANOVA and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effects of probiotic colonisation on intestinal epithelial cell barrier function

To investigate any direct effects of probiotics on our cell line models, we selected ST and LA, and exposed HT29/cl.19A and Caco-2 cells to each individual strain and to a combination of the two (ST/LA). The two probiotics were not toxic to the cell monolayers, as shown by viability measurements (trypan blue exclusion assay, and HO342 and rhodamine fluorescence staining) following incubation with various MOI (10–5000:1) of bacteria for up to 48 hours compared with untreated controls (data not shown). Furthermore, no significant bacterial overgrowth was observed over the duration of the experiment under all conditions tested. Moreover, neither strain altered the basal chloride secretory function of intestinal epithelial cells (not shown). In contrast, the combination of the two probiotics caused a small but significant increase in TER (fig 1A ▶). This effect on TER was also corroborated by the effect of ST/LA on permeability of infected monolayers to the small molecular tracer FITC (table 2 ▶). However, neither ST or LA, nor both strains in combination, altered permeability to a 10 kDa tracer (table 2 ▶). Spent medium from ST or LA cultures, ST/LA killed with antibiotics (fig 1B ▶), and heat inactivated probiotics failed to increase TER or decrease permeability to FITC (not shown). We conclude that live probiotics improve epithelial barrier properties. This is a potential mechanism contributing to their beneficial effect in vivo.

Figure 1.

Probiotic colonisation potentiates barrier function in Caco-2 monolayers. Caco-2 cells were exposed to living (A) or antibiotic killed (a) (B) Streptococcus thermophilus (ST) and Lactobacillus acidophilus (LA), alone or in combination. Transepithelial resistance (TER) was measured at the time points indicated. Resistance values of cell free inserts were subtracted from each measurement. Data are means (SEM), n=10. Where error bars are not shown, they are obscured by the symbols. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 compared with uninfected controls (by ANOVA). SM, spent medium.

Table 2.

Permeability of HT29/cl.19A and Caco-2 cells after treatment with EIEC and ST/LA in vitro

| Clearance (nl/cm2/h) | ||

| Bacteria†/probe | HT29/cl.19A | Caco-2 |

| Control | ||

| FS | 395 (88) | 532 (110) |

| FITC-D10 | 98 (22) | 126 (35) |

| S thermophilus | ||

| FS | 276 (33) | 321 (66)* |

| FITC-D10 | 82 (15) | 89 (34) |

| L acidophilus | ||

| FS | 245 (14)* | 299 (30)* |

| FITC-D10 | 80 (9) | 91 (21) |

| ST/LA | ||

| FS | 214 (21)* | 236 (26)** |

| FITC-D10 | 78 (11) | 84 (9) |

| EIEC | ||

| FS | 16590 (3318)*** | 17775 (4050)*** |

| FITC-D10 | 3010 (1185)*** | 3826 (957)*** |

| ST/LA+EIEC† | ||

| FS | 408 (125) | 453 (99) |

| FITC-D10 | 123 (36) | 155 (37) |

| ST/LA/EIEC‡ | ||

| FS | 13872 (2295)*** | 16358 (3922)*** |

| FITC-D10 | 4973 (1104)*** | 3349 (1003)*** |

| EIEC (ST/LA)§ | ||

| FS | 18529 (4185)*** | 16554 (2939)*** |

| FITC-D10 | 4666 (1010)*** | 3935 (1230)*** |

†Bacteria MOI (multiplicity of infection)=50:1; permeability assays were performed at 12 hours after infection; experiments were performed three times in triplicate.

‡Pretreatment with ST/LA followed by EIEC infection.

‡Simultaneous inoculation of the three strains.

§EIEC infection followed by ST/LA treatment.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, clearance values significantly different from corresponding control values (by ANOVA).

ST/LA, Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus; EIEC, enteroinvasive Escherichia coli; FS, fluorescein sulphonic acid; FITC-D10, fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran-10S.

Pretreatment with probiotics prevents EIEC induced decrease in TER

We and others have previously shown that a prominent effect of invasive pathogens is to reduce TER.7,8,12,16,17,19 Because probiotics alone improved epithelial barrier function, we next explored whether they might also abrogate the deleterious effects of pathogens on this parameter. HT29/cl.19A (fig 2A ▶) or Caco-2 (not shown) cells were exposed to medium alone, to ST/LA and EIEC, or to EIEC or ST/LA alone. Probiotic treatment consisted of live bacteria, antibiotic killed, or heat inactivated preparations. EIEC caused a decline in TER beginning at 6–12 hours after infection compared with uninfected control monolayers whereas pretreatment with live probiotics prevented this effect. The EIEC evoked fall in TER was also partially attenuated if cell monolayers were exposed simultaneously to probiotics and EIEC, but not if the cells were infected with EIEC for one hour and then exposed to ST/LA . However, if the probiotic inoculum was increased to >5000:1, some reversal of EIEC induced barrier dysfunction could be seen even when probiotics were added one hour after EIEC (data not shown). However, if antibiotic killed or heat inactivated probiotics, or ST/LA spent medium were used to perform the assays described above, no reversal of the effect of EIEC was seen (fig 2B ▶). We conclude that pretreatment with live probiotics reverses the decrease in TER induced by EIEC infection.

Figure 2.

Pretreatment with probiotics prevents enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) induced decrease in transepithelial resistance (TER) of polarised HT29/cl.19A cell monolayers. HT29/cl.19A cells were exposed to medium, EIEC followed by Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus (EIEC+ST/LA), EIEC and ST/LA given simultaneously (EIEC/ST/LA), EIEC alone, ST/LA followed by EIEC (ST/LA+EIEC), or ST/LA alone on the apical side. Preparations of living (A), antibiotic killed (a) (B), heat inactivated (h) (B), or spent medium (SM) from ST and LA cultures (B) were tested in these experiments. TER was measured at the times indicated. Resistance values of cell free inserts were subtracted from each measurement. Data are means (SEM), n=8. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 compared with uninfected controls (by ANOVA). Similar findings were observed in Caco-2 cells.

Pretreatment with probiotics prevents EIEC induced increases in epithelial permeability to small molecules and macromolecules

The effects of EIEC, with or without probiotics, on TER measurements was suggestive of corresponding effects on epithelial permeability. To examine this directly, we measured the flux of two fluorescent probes of differing size across infected and control monolayers. After infection with EIEC, the permeability of HT29/cl.19A and Caco-2 cells, expressed as clearance of the two fluorescent probes tested, was markedly increased and the alteration was proportionally greater for the smaller probe (table 2 ▶). Moreover, pretreatment only with live probiotics prevented the increase in permeability induced by EIEC infection for up to 24 hours after EIEC exposure in both cell lines whereas antibiotic killed or heat inactivated ST/LA failed to exert this effect. Furthermore, simultaneous inoculation of ST/LA and EIEC at equivalent MOI, or exposure of the cells to probiotics one hour after EIEC infection, also failed to prevent the increase in FS or FITC-D10 permeability (table 2 ▶). Moreover, even at higher MOI, simultaneous addition of probiotics failed to prevent permeability changes induced by EIEC despite the fact that this treatment reduced EIEC invasion (see below).

Pretreatment with probiotics limits colonisation of EIEC in epithelial cell monolayers

We next explored whether our probiotic preparation altered the interaction of EIEC with the epithelium. As shown in table 3 ▶, the number of adhered EIEC was significantly reduced when monolayers were preincubated with equal numbers of each of ST and LA. Moreover, if the relative numbers of the probiotic strains were increased while the EIEC inoculum remained constant at 50:1, adhesion of EIEC was essentially abolished, particularly at later time points. Simultaneous addition of probiotics and EIEC was also able to inhibit adhesion of the latter bacteria, although only with an increased number of probiotics and to a lesser extent than seen with preincubation. In contrast, if probiotics were added one hour after EIEC infection, no significant effect on EIEC adhesion was seen. Interestingly, antibiotic killed ST/LA maintained the ability to inhibit EIEC adhesion, whereas heat inactivated probiotics or spent medium did not (table 3 ▶).

Table 3.

Effect of ST/LA on adhesion† of EIEC to Caco-2 cell monolayers

| Time after EIEC addition (h) | |||||

| Probiotic treatment | Ratio of MOI‡ (ST/LA:EIEC) | 1 | 2 | 3 | Significance |

| None | N/A | 24 (3) | 27 (1) | 17 (5) | — |

| Live ST/LA 1 h prior to EIEC | 2:1 | 6 (2) | 5 (1) | 5 (2) | ** |

| 20:1 | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | *** | |

| 200:1 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | *** | |

| Live ST/LA simultaneous with EIEC | 2:1 | 19 (4) | 21 (4) | 24 (3) | NS |

| 20:1 | 15 (3) | 17 (2) | 11 (5) | NS | |

| 200:1 | 5 (1) | 7 (3) | 5 (1) | ** | |

| Live ST/LA 1 h after EIEC | 2:1 | 22 (5) | 29 (3) | 25 (2) | NS |

| 20:1 | 20 (4) | 23 (1) | 22 (3) | NS | |

| 200:1 | 21 (5) | 22 (2) | 23 (1) | NS | |

| ST/LA (antibiotic killed) 1 h prior to EIEC | 2:1 | 10 (2) | 9 (1) | 10 (1) | ** |

| 20:1 | 7 (1) | 7 (1) | 8 (1) | ** | |

| 200:1 | 3 (1) | 3 (2) | 3 (1) | ** | |

| ST/LA (antibiotic killed) simultaneous with EIEC | 2:1 | 18 (2) | 19 (1) | 18 (1) | * |

| 20:1 | 16 (1) | 16 (2) | 15 (1) | * | |

| 200:1 | 5 (1) | 7 (2) | 5 (1) | ** | |

| ST/LA (heat inactivated) 1 h prior to EIEC | 2:1 | 22 (1) | 25 (2) | 23 (2) | NS |

| 20:1 | 20 (1) | 23 (1) | 20 (1) | NS | |

| 200:1 | 21 (2) | 20 (2) | 20 (1) | NS | |

| ST/LA sp medium§ simultaneous with EIEC | 25 (2) | 23 (2) | 22 (1) | NS | |

†Mean (SEM) of adherent EIEC per 100 cells examined in 20 random microscopic fields, for four experiments in duplicate.

‡MOI=multiplicity of infection. EIEC was applied at 50:1 throughout.

§ST/LA spent medium from 48 hour cultures was filtered, lyophilised, and concentrated 10×.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, data sets significantly different from EIEC with no probiotics (by repeated measures ANOVA).

ST/LA, Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus; EIEC, enteroinvasive Escherichia coli.

Figure 3A ▶ and 3B ▶ depict EIEC invasion of intestinal epithelial cells under the various conditions tested. Gentamicin was added after one hour of EIEC infection to eliminate extracellular bacteria. These data paralleled, in part, those presented above for adhesion. Thus pretreatment with probiotics markedly reduced EIEC invasion, simultaneous addition of probiotics and EIEC had a lesser, but still significant, effect, and addition of probiotics one hour after EIEC failed to reduce invasion. For all conditions tested, the protective effect of probiotics was proportional to the size of probiotic inoculum and plateaued between 102–103:1 MOI for pretreatment (fig 3B ▶) and 103:1 MOI in the case of simultaneous inoculation (fig 3C ▶). In contrast, the ability of antibiotic killed or heat inactivated ST/LA to inhibit EIEC invasion and colonisation was severely impaired (fig 3A ▶). In fact, even when ST/LA killed with antibiotics were added to the monolayers before EIEC challenge, a condition that was as effective as live ST/LA in reducing EIEC adhesion, the level of invading organisms was not reduced compared with controls. However, pretreatment with inactivated probiotics plus spent ST/LA culture medium partly restored the ability of ST/LA to limit invasion of EIEC (fig 3D ▶). These data suggest that probiotics exert their effects through multiple levels of interaction with host cells and invading organisms.

Figure 3.

Pretreatment with probiotics significantly reduces enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) invasion of infected Caco-2 cell monolayers. (A) Caco-2 cells were exposed to EIEC alone, Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus followed by EIEC (ST/LA+EIEC), ST/LA and EIEC simultaneously (ST/LA/EIEC), or EIEC followed by ST/LA (EIEC+ST/LA), and treated with gentamicin one hour after EIEC infection to kill extracellular bacteria. Living, antibiotic killed (a), and heat inactivated (h) ST and LA were tested in these experiments. Cell lysates were plated on agar for colony forming unit (CFU) counts in the experiments shown. (B) (pretreatment) and (C) (simultaneous treatment) summarise invasion data obtained at various ST/LA multiplicity of infection (MOI) (EIEC 50:1 MOI). (D) Results of invasion in cell monolayers pretreated with inactivated probiotics plus their spent medium (SM) or spent medium alone. Data are means (SEM), n=6. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 compared with cells infected with EIEC in the absence of probiotics (by ANOVA).

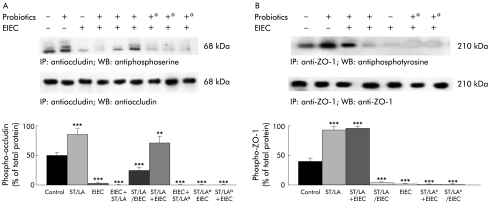

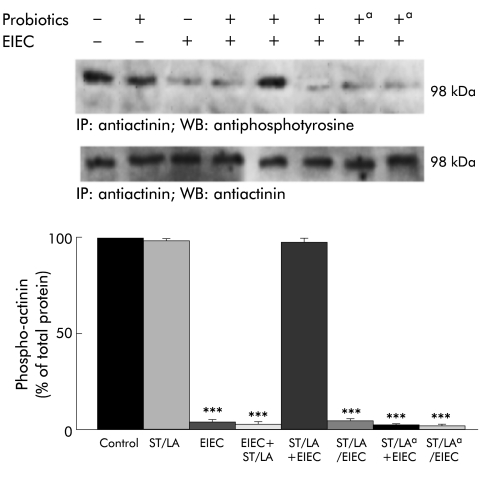

Pretreatment with probiotics prevents disruption of cytoskeletal and tight junctional protein localisation and phosphorylation

The ability of probiotics to reduce effects of EIEC on TER suggest that probiotics may modify the cytoskeleton and tight junctions. We analysed the phosphorylation status and abundance of selected cytoskeletal and tight junctional proteins, as summarised in fig 4A ▶ and 4B ▶. Infection with EIEC caused a significant reduction in serine phosphorylation of occludin (fig 4A ▶) and tyrosine phosphorylation of ZO-1 (fig 4B ▶), without a major change in the abundance of these proteins. These effects were completely prevented if cells were pretreated with live probiotics prior to EIEC infection (fig 4 ▶). Simultaneous treatment with probiotics had a significant effect only at MOI ⩾103:1 (data not shown). Similarly, EIEC significantly reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of actinin (fig 5 ▶), an effect shown elsewhere34–38 to correlate with disruption of actin filaments. Again, this deleterious response was reduced by live probiotic pretreatment or simultaneous treatment at high MOI (103:1), but not by antibiotic killed ST/LA (fig 5 ▶). These data emphasise the multiplicity of interactions of probiotic ST/LA in our model, and underscore the complex correlation between barrier function and cytoskeletal and tight junction homeostasis in the intestinal epithelium. Again, they also imply that invasion of EIEC is needed to effect changes in tight junction proteins.

Figure 4.

Infection with enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) alters phosphorylation of the tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1. HT29/Cl.19A cell monolayers were exposed to medium, Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus (ST/LA) (multiplicity of infection=50:1), EIEC, or ST/LA followed by EIEC. Both living and antibiotic killed (a) ST and LA were tested in these experiments. Cells were harvested at 12 hours after infection. Whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies against occludin (A) or ZO-1 (B), then blotted with the same antibody or with an antiphosphoserine (A) or antiphosphotyrosine (B) antibody. The upper panels are representative blots whereas the lower panels show means (SEM) for densitometric analyses, n=6. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 compared with uninfected controls (by ANOVA).

Figure 5.

Pretreatment with probiotics prevents actinin dephosphorylation in enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) infected Caco-2 cell monolayers. Caco-2 cell monolayers were exposed to medium, Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus (ST/LA) (multiplicity of infection=50:1), EIEC, ST/LA and EIEC simultaneously (ST/LA/EIEC), EIEC followed by ST/LA (EIEC+ST/LA), or ST/LA followed by EIEC (ST/LA+EIEC) and cells were harvested at 12 hours after infection. Both living and antibiotic killed (a) ST and LA were tested in these experiments. Whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies against α-actinin, then blotted with the same antibody or an antiphosphotyrosine antibody. The upper panel shows representative blots whereas the lower panel shows means (SEM) for densitometric analyses, n=6. ***p<0.001 compared with uninfected controls (by ANOVA)

Pretreatment with probiotics limits ion transport dysfunction associated with EIEC infection of epithelial cells

We have previously shown7,8,12 that enteroinvasive bacteria increase basal chloride secretion by intestinal epithelial cells. Furthermore, infection with enteroinvasive bacteria alters the expression and abundance of specific transport proteins.12 To test if probiotics prevent these effects, we measured Isc, an indicator of chloride secretion, in Ussing chambers. As shown in fig 6A ▶, and as expected on the basis of previous studies,12 EIEC induced a significant increase in basal Isc compared with untreated controls and ST/LA treated cells as early as 1–3 hours after infection. Furthermore, pretreatment with ST/LA completely prevented the effect of EIEC infection on Isc. However, even much higher MOIs of probiotics (>103:1) failed to limit EIEC induced alterations in baseline Isc if the probiotics were added simultaneously with or one hour after EIEC (not shown) despite reduced colonisation in the former case. Furthermore, if the probiotic preparation was killed by pretreatment with antibiotics, ST/LA failed to induce any significant protective effect against increased baseline Isc in monolayers infected with EIEC. On the other hand, spent medium from ST/LA cultures plus an antibiotic treated probiotic inoculum, although not heat inactivated ST/LA plus spent medium, partially reversed the increased basal Isc of EIEC infected monolayers if added simultaneously with the enteropathogen (fig 6B ▶). This stands in considerable contrast with failure of spent medium to reverse effects of EIEC on other epithelial parameters discussed previously, or to prevent EIEC adhesion. This underscores the fact that probiotics alter responses to pathogens via numerous mechanisms, not all of which are related to prevention of epithelial colonisation.

Figure 6.

Pretreatment with probiotics limits enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) induced increases in chloride secretion. HT29/Cl.19A cells were exposed to medium, EIEC, Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus (ST/LA)+EIEC, or ST/LA alone on the apical side. Preparations of living or antibiotic killed (a) ST/LA, or spent medium (SM) from ST and LA cultures were tested in these experiments. Short circuit current (Isc), an indicator of chloride secretion, was measured at the times indicated. Data are means (SEM), n=6. ***p<0.001 compared with uninfected controls (by ANOVA).

In previous studies,12 EIEC infection potentiated the secretory response of epithelial cells to the neuropeptide galanin. This would be expected to contribute to an infection associated increase in fluid and electrolyte secretion in vivo.21,22 Pretreatment with ST/LA blocked the ability of EIEC to potentiate secretion evoked by galanin (fig 7 ▶). Again, simultaneous exposure to EIEC and probiotics or addition of probiotics after EIEC failed to reverse the potentiated secretion (fig 7 ▶), independent of the size of the probiotic inoculum. These findings correlate to some degree to the results of adhesion and invasion experiments, although reduced adhesion evoked by simultaneous addition of probiotics and EIEC, especially at higher ST/LA MOIs, is not sufficient to prevent pathogen evoked hypersecretion. On the other hand, ST/LA spent medium was able to substantially prevent EIEC induced hypersecretory responses to galanin. As before, our data underscore the fact that both live probiotics and their secreted products can impact epithelial responses to pathogens but only the former can exert the full spectrum of preventative effects.

Figure 7.

Pretreatment with probiotics prevents galanin stimulated chloride secretory responses in enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) infected HT29/cl.19A cell monolayers. HT29/cl.19A cell monolayers were exposed to medium alone, Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus (ST/LA) alone, EIEC alone, ST/LA followed by EIEC (ST/LA+EIEC), ST/LA and EIEC simultaneously (ST/LA/EIEC), or EIEC followed by ST/LA (EIEC+ST/LA), or spent medium (SM) from ST and LA cultures with or without EIEC. Preparations of living or antibiotic killed (a) ST/LA were used. Monolayers were mounted in Ussing chambers at the times indicated and chloride secretory responses to galanin (100 nM) assessed as maximal increases in short circuit current (ΔIsc). *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 compared with uninfected controls (by ANOVA).

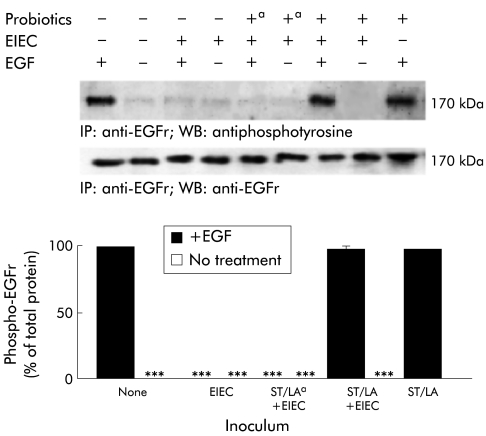

Pretreatment with probiotics prevents EGF receptor inactivation induced by EIEC invasion

EIEC infection can prevent activation and/or increased degradation of the EGFr.7,8 Given the critical role of EGF and the EGFr in many aspects of gastrointestinal physiology and epithelial repair,23 we hypothesised that the beneficial effect of probiotics might extend to their ability to restore EGFr signalling in epithelial cells infected with EIEC. In fact, when cells were pretreated with probiotics, infected with EIEC, then stimulated with EGF, EGFr activation was significantly preserved compared with cells infected with EIEC alone (fig 8 ▶). However, this effect was not seen if probiotics were added simultaneously with or after EIEC, or with antibiotic killed probiotics.

Figure 8.

Pretreatment with probiotics prevents epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFr) inactivation by enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC). HT29/cl.19A cell monolayers were exposed to medium, Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus (ST/LA), EIEC, or ST/LA followed by EIEC. Both living and antibiotic killed (a) ST and LA were tested in these experiments. Before harvest at three hours after infection, cells were treated with EGF (50 nM, two minutes) or medium alone. After lysis and immunoprecipitation with anti-EGFr, proteins were electrophoresed and blotted with the same antibody or with antiphosphotyrosine. The top panel shows representative blots whereas the bottom panel shows means (SEM) for densitometric analyses, n=6. ***p<0.001 compared with uninfected cells stimulated with EGF (by ANOVA) (n=4, means (SEM)).

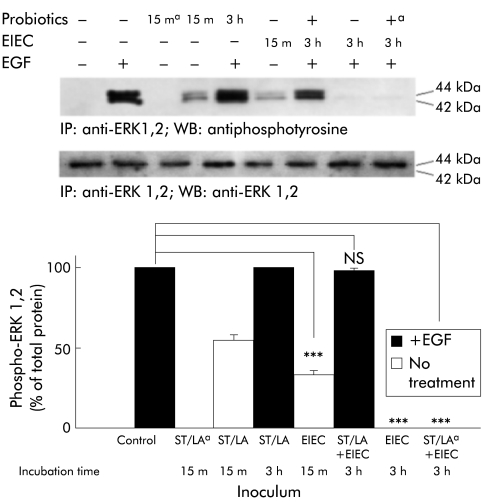

Mitogen activated protein kinases are downstream effectors of the EGFr. Both EIEC and live probiotics induced early phosphorylation of the ERK 1,2 isoform of these kinases (fig 9 ▶). Antibiotic killed (fig 9 ▶) or heat inactivated (not shown) ST/LA were unable to activate ERK1/2. We also tested whether ERK 1 and 2 were activated under the various conditions studied following EGF stimulation. Pretreatment with live probiotics reversed the inhibition of ERK 1 and 2 activation induced by EIEC infection in a significant fashion (fig 9 ▶). There was no significant change in total ERK levels under any condition. Antibiotic killed (fig 9 ▶) or heat inactivated (not shown) probiotics failed to reverse the effects of EIEC infection on EGF induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (fig 9 ▶). These data further corroborate that probiotics likely have myriad protective effects in the intestinal epithelium.

Figure 9.

Effect of probiotics and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) on basal and epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulated ERK 1 and 2 activation. HT29/cl.19A cell monolayers were exposed to medium, Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus (ST/LA), EIEC, or ST/LA followed by EIEC. Both living and antibiotic killed (a) ST and LA were tested in these experiments. ERK 1 and 2 were also activated under the various conditions studied following EGF stimulation. The top panel shows two representative blots whereas the bottom panel shows means (SEM) for densitometric analyses. ***p<0.001 compared with uninfected cells (by ANOVA, n=6).

DISCUSSION

The role of commensal and probiotic bacteria in the physiology of the gastrointestinal tract is incompletely understood. In particular, the mechanisms underlying the benefits derived from biotherapy with probiotics have not been sufficiently elucidated, with available data largely fragmentary and/or anecdotal. It is known that stimulation by commensal bacterial antigens is crucial for the normal development of the mucosal immune system and maintenance of tolerance.3,6 Moreover, probiotics have been shown to attenuate or abolish tumour necrosis factor α stimulated interleukin 8 production in intestinal epithelial cells.24,25 The studies described here show in addition that, by diverse mechanisms, living probiotics are able to prevent or counteract the full spectrum of epithelial dysfunction induced by an enteroinvasive pathogen. In addition, probiotics alone, in the absence of EIEC infection, had effects that are arguably beneficial. Thus addition of live probiotics to naïve epithelial monolayers resulted in a progressive increase in their TER and an accompanying decrease in their permeability to a low molecular weight tracer.

Our findings demonstrate the ability of live probiotic bacteria to interfere with enteric pathogens through diverse mechanisms. Our data concur with recent work from other laboratories24,25–33 in showing an important, but not exclusive, role for probiotic induced interruption of the early interactions of pathogens and host cells. Mack et al showed that part of the beneficial effect of L plantarum and L ramnosus was mediated by induction of mucin genes in intestinal epithelial cells, thus preventing adherence of enteropathogenic E coli.33 We do not know yet if S thermophilus or L acidophilus have similar effects in our models. However, only pretreatment with probiotics prevented invasion of EIEC into epithelial cells and some, but not all, aspects of epithelial dysfunction associated with invasion, whereas simultaneous exposure to both probiotic and pathogenic bacteria had lesser preventative effects, especially at equivalent MOIs.

In our study, probiotic exposure following EIEC infection of epithelial monolayers had essentially no ability to prevent colonisation and invasion, or functional sequelae. Our findings are mirrored in the reported need to administer large doses of probiotics in vivo when attempting to control or attenuate ongoing gastrointestinal infections or inflammation.5,25 Specifically, Madsen et al showed that the use of a single probiotic strain alone was beneficial in reducing disease in IL-10 deficient mice only at high densities.25,27 Moreover, work in our laboratory suggests that different probiotics produce differing levels of bactericidal proteins with various degrees of efficacy against enteric pathogens, as well as autoinducers that can condition the formation of complex biofilms above the epithelial surface, conceivably thus modulating mucosal responses to the lumenal environment (Resta- Lenert et al, unpublished observations). These findings emphasise the importance of investigating a diversity of host-microorganism interactions when profiling probiotics. Probiotics which display different characteristic phenotypes may be valuable as therapeutic tools under different pathophysiological conditions.

While either pretreatment or simultaneous inoculation (at appropriate MOIs) with live probiotics could limit EIEC invasion and TER alterations in epithelial cells, only pretreatment with live ST/LA was able to block the effect of EIEC on chloride secretion in our models. Interestingly however ST/LA spent medium also restored normal transport function. These data emphasise the divergent regulation of cellular secretory and barrier functions. Moreover, the findings imply that the consequences of bacterial invasion, either in terms of bacterial products or host factors, are able to dysregulate secretory function well before bacterial invasion disrupts barrier properties. In previous studies,12 we have shown that epithelia respond very rapidly to invasive pathogenic bacteria with production of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide as well as altered chloride secretion, indicating that both bacterial killing and “flushing out” may be firstline defence mechanisms against the threat of invasion of the gastrointestinal mucosa. In this regard, it is perhaps fortuitous that probiotics, as administered clinically after infection has begun, might be unlikely to inhibit these putatively beneficial adaptive responses to an infectious threat.

By preventing invasion and extensive colonisation, probiotics considerably reduce the infective load and thus the oxidative stress that is in part responsible for the acute mucosal inflammation induced by enteric pathogens.12 Inhibition of oxidative stress at the site of mucosal infection might prevent EGFr inactivation as observed as a consequence of acute in vitro infection with EIEC or rotavirus.7,8 It is well known that EGF and activation of the EGFr promote epithelial restitution after injury in several gastrointestinal pathological conditions23 and that EGF therapy produces improvement in colitis and gastric ulcers in both in vivo and in vitro models.29–32 EGF also regulates cell motility, proliferation, and maintenance of cell size and shape.34–43 Our data show that probiotic pretreatment is able to preserve EGFr function that would otherwise be affected adversely by EIEC invasion. This observation likely implies an important mechanism whereby probiotics could improve mucosal function in a wide variety of intestinal disorders, given the protean functions of EGF and related growth factors in the gastrointestinal tract.

In conclusion, we have shown functionally significant interactions that are likely to occur between intestinal epithelial cells and intimately associated living probiotic bacteria. Only live probiotics were shown to have beneficial effects on epithelial barrier function when added by themselves, and to prevent a number of deleterious consequences otherwise evoked by infection of the epithelium with an invasive pathogen. In contrast, even probiotic supernatants were capable of reproducing some of the beneficial effects of these bacteria, without preventing pathogen adhesion. If similar mechanisms pertain in vivo, our findings could provide a scientific rationale for the anecdotal efficacy of probiotics in a variety of intestinal disorders. Furthermore, additional elucidation of the precise mechanisms whereby individual probiotic strains exert beneficial and protective effects might optimise such therapies, which already enjoy wide patient acceptance due to their safety and “natural” provenance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Glenda Wheeler for secretarial assistance, and Dr Josh Fierer for supplying the EIEC strain used in this work. These studies were supported by NIH grant DK35108 (Unit 5), a grant from the Crohn’s and Colitis foundation of America to KEB, and an NIH supplemental award to SRL. A preliminary account of this work was presented at annual meetings of the American Gastroenterological Association (2000, 2001) and at the “Gastrointestinal response to injury” meeting, Quebec, Canada (2001), and has been published in abstract form (Gastroenterology 2000;118:4325; Gastroenterology 2001;120:3801). KE Barrett is a member of the Biomedical Sciences PhD Program, UCSD School of Medicine.

Abbreviations

ST/LA, Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus

EIEC, enteroinvasive Escherichia coli

TSB, trypticase soy broth

TSA, trypticase soy agar

MRS, deMane-Rogosa-Sharpe broth

TER, transepithelial resistance

EGF, epidermal growth factor

EGFr, epidermal growth factor receptor

MOI, multiplicity of infection

CFU, colony forming unit

PBS, phosphate buffered saline

FS, fluorescein sulphonic acid

FITC-D10, fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran-10S

Isc, short circuit current

REFERENCES

- 1.Elson CO, Cong Y, Iqbal N, et al. Immuno-bacterial homeostasis in the gut: new insight into an old enigma. Sem Immunol 2001;13:187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filho-Lima JVM, Vieira EC, Nicoli JR. Antagonistic effect of L.acidophilus, S. boulardii and E.coli combinations against experimental infections with S. flexneri and S. typhimurium in gnotobiotic mice. J Appl Microbiol 2000;88:365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg S, Bal V, Rath S, et al. Effect of multiple antigenic exposures in the gut on oral tolerance and induction of antibacterial systemic immunity. Infect Immun 1999;67:5917–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lilly DM, Stillwell RH. Probiotics: growth promoting factors produced by microorganisms. Science 1965;47:747–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Venturi A, et al. Oral bacteriotherapy as maintenance treatment in patients with chronic pouchitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2000;119:305–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooper LV, Wong MH, Thelin A, et al. Molecular analysis of commensal host- microbial relationships in the intestine. Science 2001;291:881–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resta-Lenert S, Barrett KE. Modulation of tight junction structure by enteroinvasive E.coli (EIEC) is prevented by H2O2 scavengers and protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitors. Gastroenterology 2001;120:3802. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Resta-Lenert S, Barrett KE. Increased expression of iNOS and COX-2 is associated with activation of chloride currents in HT29/Cl.19A cells infected by enteroinvasive bacteria. Gastroenterology 2000;118:4325. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Resta-Lenert S, Truong F, Barrett KE, et al. Inhibition of epithelial chloride secretion by butyrate: role of reduced adenylyl cyclase expression and activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2001;281:C1837–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buret A, Gall DG, Olson ME, et al. The role of epidermal growth factor receptor in microbial infections of the gastrointestinal tract. Microbes Infect 1999;1:1139–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galan JE, Pace J, Hayman MJ. Involvement of the epidermal growth factor receptor in the invasion of cultured mammalian cells by S.typhimurium. Nature 1992;357:588–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resta-Lenert S, Barrett KE. Infection with enteroinvasive bacteria alters barrier function and transport properties of human intestinal epithelial cells: role of iNOS and COX- 2 expression. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1070–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bertelsen LS, Resta-Lenert S, Barrett KE. Salmonella dublin infection inhibits chloride secretion in T84 cells. Gastroenterology 2000;118:4307. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resta-Lenert S, Barrett KE. Rotavirus infection induces increased chloride secretion, altered barrier function and epidermal rowth factor receptor (EGF-R) polyubiquitination in an intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) line. Gastroenterology 2001;120:3801. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sears CL. Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of tight junctions V. Assault of the tight junction by enteric pathogens. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2000;279:G1129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolton AJ, Osborne MP, Stephen J. Comparative study of the invasiveness of Salmonella serotypes Typhimurium, Choleraesuis and Dublin for Caco-2 cells, HEp-2 cells and rabbit ileal epithelia. J Med Microbiol 2000;49:503–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simonovic I, Rosenberg J, Koutsouris A, et al. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli dephosphorylates and dissociates occludin from intestinal epithelial tight junctions. Cell Microbiol 2000;2:305–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keely SJ, JM Uribe, KE Barrett. Carbachol stimulates transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor and mitogen-activated protein kinase in T84 cells. Implications for carbachol-stimulated chloride secretion. J Biol Chem 1998;273:27111–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Resta-Lenert S, Langford TD, Gillin FD, et al. Altered chloride secretory responses in HT29/Cl.19A cells infected with Giardia lamblia. Gastroenterology 2000;118 :3759. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goosney DL, De Vinney R, Pfuetzner RA, et al. Enteropathogenic E.coli translocated intimin receptor, Tir, interacts directly with alpha-actinin. Curr Biol 2000;10:735–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hecht G, Marrero JA, Danilkovitch A, et al. Pathogenic E.coli increases Cl−secretion from intestinal epithelia by upregulating galanin-1 receptor expression. J Clin Invest 1999;104:253–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nataro JP, Kaper JB. Diarrheagenic E. coli. Clin Microbiol Rev 1998;11:142–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riegler M, Sedivy R, Sogukoglu T, et al. Effect of growth factors on epithelial restitution of human colonic mucosa in vitro. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32:925–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gopal PK, Prasad J, Smart J, et al. In vitro adherence properties of L. rhamnosus DR20 and B. lactis DR10 strains and their antagonistic activity against an enterotoxigenic E.coli. Int J Food Microbiol 2001;67:207–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madsen K, Cornish A, Soper P, et al. Probiotic bacteria enhance murine and human intestinal epithelial barrier function. Gastroenterology 2001;121:580–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kruis W, Schutz E, Fric P, et al. Double-blind comparison of an oral E. coli preparation and mesalazine in maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1997;11:853–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madsen KL, Doyle JS, Jewell LD, et al Lactobacillus species prevents colitis in interleukin-10 gene-deficient mice. Gastroenterology 1999;116:1107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rembacken BJ, Snelling AM, Hawkey PM, et al. Non-pathogenic E.coli versus mesalazine for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a randomized trial. Lancet 1999;354:635–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venturi A, Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, et al. Impact on the composition of the faecal flora by a new probiotic preparation: preliminary data on maintainance treatment of patients with ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999;13:1103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner ED, Warner T, Roberts L, et al. Colonization of congenitally immunodeficient mice with probiotic bacteria. Infect Immun 1997;65:3345–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogawa M, Shimizu K, Nomoto K, et al. Inhibition of in vitro growth of Shiga toxin- producing E. coli O157:H7 by probiotic Lactobacillus strains due to production of lactic acid. Int J Food Microbiol 2001;68:135–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Czerucka D, Dahan S, Mograbi B, et al. Saccharomyces boulardii preserves barrier function and modulates the signal transduction pathway induced in EPEC-infected T84 cells. Infect Immun 2000;68:5998–6004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mack DR, Michail S, Wei S, et al. Probiotics inhibit enteropathogenic E.coli adherence in vitro by inducing intestinal mucin gene expression. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 1999;276:G941–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buret A, Olson ME, Gall DG, et al. Effects of orally administered epidermal growth factor on enteropathogenic E. coli infection in rabbits. Infect Immun 1998;66:4917–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Procaccino F, Reinshagen M, Hoffman P, et al. Protective effect of epidermal growth factor in an experimental model of colitis in rats. Gastroenterology 1994;107:12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tarnawski AS, Jones MK. The role of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and its receptor in mucosal protection, adaptation to injury, and ulcer healing: involvement of EGF-R signal transduction pathways. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998;27:12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elliott SN, Wallace JL, McKnight W, et al. Bacterial colonization and healing of gastric ulcers: the effects of epidermal growth factor. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2000;278:G105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X, McCullough KD, Frankel TF, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent Akt activation by oxidative stress enhances cell survival. J Biol Chem 2000;275:14624–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamata H, Shibukawa Y, Oka SI, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor is modulated by redox through multiple mechanisms. Eur J Biochem 2000;267:1933–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rijiken PJ, van Hal GJ, van der Hayden MAG, et al. Actin polymerization is required for negative feedback regulation of epidermal growth factor-induced signal transduction. Exp Cell Res 1998;243:254–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Wit R, Capelo A, Boonstra J, et al. Hydrogen peroxide inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor internalization in human fibroblasts. Free Rad Biol Med 2000;28:28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Banan A, Zhang Y, Losurdo J, et al. Carbonylation and disassembly of the F-actin cytoskeleton in oxidant induced barrier dysfunction and its prevention by epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor alpha in a human colonic cell line. Gut 2000;46:830–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zushi S, Shinomura Y, Kiyohara T, et al. Role of prostaglandins in intestinal epithelial restitution stimulated by growth factors. Am J Physiol 1996;270:G757–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]