Abstract

Background and aims: In HFE associated hereditary haemochromatosis, the duodenal enterocyte behaves as if iron deficient and previous reports have shown increased duodenal expression of divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) and iron regulated gene 1 (Ireg1) in affected subjects. In those studies, many patients had undergone venesection, which is a potent stimulus of iron absorption. Our study investigated duodenal expression of DMT1 (IRE and non-IRE), Ireg1, hephaestin, and duodenal cytochrome-b (Dyctb) in untreated C282Y homozygous haemochromatosis patients, iron deficient patients, and iron replete subjects.

Methods: Total RNA was extracted from duodenal biopsies and expression of the iron transport genes was assessed by ribonuclease protection assay.

Results: Expression of DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 was increased 3–5-fold in iron deficient subjects compared with iron replete subjects. Duodenal expression of DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 was similar in haemochromatosis patients and iron replete subjects but in haemochromatosis patients with elevated serum ferritin concentrations, both DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 expression were inappropriately increased relative to serum ferritin concentration. Hephaestin and Dcytb levels were not upregulated in haemochromatosis. DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 levels showed significant inverse correlations with serum ferritin concentration in each group of patients.

Conclusions: These findings are consistent with DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 playing primary roles in the adaptive response to iron deficiency. Untreated haemochromatosis patients showed inappropriate increases in DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 expression for a given level of serum ferritin concentration, although the actual level of expression of these iron transport genes was not significantly different from that of normal subjects.

Keywords: haemochromatosis, iron deficiency, DMT1, Ireg1, hephaestin, Dcytb

Hereditary haemochromatosis (HHC) is a common autosomal recessive disorder of iron metabolism characterised by progressive accumulation of iron, primarily in the liver, pancreas, and heart, which may ultimately result in organ failure.1 The majority (80–90%) of patients with HHC are homozygous for a missense mutation that results in substitution of tyrosine for cysteine at position 282 (C282Y) in the haemochromatosis protein, HFE.2–4 A major pathophysiological feature of HHC is a rate of intestinal iron absorption that is inappropriately elevated for a given level of body iron stores. The precise mechanism by which HFE regulates intestinal iron absorption is unknown but the available evidence indicates that in HHC the duodenal enterocyte behaves as if it is iron deficient. This conclusion is supported by studies showing that in patients with HHC, the duodenal mucosal content of ferritin mRNA and protein is relatively low while the corresponding levels of transferrin receptor gene and protein expression are relatively high, and the binding affinity of iron regulatory protein is increased.5–8

Iron absorption involves the uptake of iron from the lumen of the small intestine into the mature duodenal enterocyte, followed by its basolateral transfer into the portal circulation.9 Kinetic studies suggest that the transfer of iron across the basolateral membrane is the main regulatory step in normal subjects and HHC patients.10–12 Each iron transport step involves a transmembrane transporter that is likely to be coupled to an enzyme that changes the oxidation state of iron. Our understanding of intestinal iron absorption has improved in recent years following identification of several key proteins involved in the trafficking of iron into and out of cells. These include divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1), iron regulated gene 1 (Ireg1 also known as SCL11A3, ferroportin1, or MTP1), hephaestin, and duodenal cytochrome-b (Dcytb).

DMT1 is a brush border transmembrane transporter for several divalent metals, including iron, copper, and zinc. It pumps iron into the enterocyte via an active proton coupled transport mechanism.13,14 At least two alternatively spliced transcripts of DMT1 exist, encoding alternative carboxy termini and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs). The 3′ UTR of one variant contains a consensus iron responsive element (IRE) sequence that binds to iron regulatory proteins. DMT1 transports ferrous iron, indicating that dietary iron (which is mainly in the ferric form) must first be reduced before it can be utilised. A strong candidate for this ferrireductase activity is Dcytb, an enzyme that was recently identified as upregulated in the duodenal mucosa of the hpx mouse.15 Dcytb localises to the brush border membranes of mature enterocytes of the upper villous region, and both protein and mRNA levels are regulated by hypoxia, iron deficiency, and anaemia.15

Ireg1 is predicted to function as an iron transporter on the basolateral membrane of the mature villous enterocyte and elevated duodenal Ireg1 mRNA levels are observed in situations associated with increased intestinal iron absorption.16–18 Ireg1 is postulated to associate with hephaestin, a membrane bound ceruloplasmin homologue with ferroxidase activity.19

Recently, Zoller et al reported 100-fold increase in duodenal DMT1 expression in 20 C282Y homozygous HHC subjects who were undergoing, or who had recently completed, therapeutic phlebotomy, compared with 10 subjects with normal body iron stores.20 Subsequently, the same authors (using a different technique) reported much lower increases, 8–10-fold and 2–5-fold in duodenal DMT1 and Ireg1 expression, respectively, in eight untreated C282Y homozygous HHC subjects compared with normal subjects, and reported that expression of these genes was similar to that observed in 19 subjects with iron deficiency.21 Rolfs et al have reported similar findings of increased DMT1 and Ireg1 expression in nine C282Y homozygous HHC subjects, all of whom had been treated to a state of iron deficiency or were undergoing venesection at the time of duodenal biopsy.22 Prior studies indicate that venesection per se causes a significant increase in iron absorption in HHC patients10,23,24 and inclusion of phlebotomised subjects may have had a confounding effect on the results of these studies. Thus despite recent advances, the relationship between body iron stores and expression of these iron transporters has not been clearly defined in untreated HHC patients. To address this, duodenal expression of DMT1, Ireg1, hephaestin, and Dcytb was investigated in untreated C282Y homozygous HHC patients, subjects with iron deficiency, and subjects with normal biochemical iron indices. Expression of these iron transport genes was related to serum iron indices and haematological parameters.

METHODS

Study population

Twelve C282Y homozygous HHC patients, 11 subjects with iron deficiency, and 13 iron replete subjects (that is, normal serum iron indices) were studied. The 12 HHC subjects were diagnosed in a tertiary hospital phenotypic screening study25 whereby subjects with a corrected total iron binding capacity ⩾40% were genotyped for the common mutations in the HFE gene. All subjects homozygous for the C282Y mutation were contacted and reviewed in a dedicated hepatology clinic. Percutaneous liver biopsy was performed at the time of diagnosis in six HHC subjects, all of whom had (i) a serum ferritin concentration (SF) ⩾1000 μg/l, (ii) elevated serum alanine or aspartate transaminase levels, (iii) hepatomegaly (assessed either clinically or ultrasonographically)26 and/or (iv) coexistent cause for liver disease. Hepatic iron stores were assessed and graded following Perls’ Prussian blue stain by a single hepatopathologist according to the method described by Searle and colleagues.27 Quantitative hepatic iron measurements were performed on fresh liver tissue using a modification of the colorimetric method of Torrance and Bothwell.28

All study subjects underwent gastroscopy for investigation of a range of clinical indications, including dyspepsia, iron deficiency, anaemia, heartburn, or dysphagia. For the purposes of this study, iron deficiency was defined as a transferrin saturation (TS) of <15% and an SF of <30 μg/l, or documented absence of iron stores on bone marrow biopsy. Subjects in the iron replete group had serum iron indices within the laboratory reference ranges (that is, TS 15–45%; SF 30–300 μg/l). HFE genotyping was determined in non-HHC subjects, as described elsewhere.4

Fasting serum iron indices and haematological parameters were measured in all 36 subjects within two weeks of gastroscopy. Patient records were reviewed for a history of red blood cell or iron transfusions, or upper gastrointestinal bleeding during the weeks preceding gastroscopy. None of the subjects was a regular blood donor or taking oral iron during the study. Written consent was obtained from all subjects and the study was approved by the Princess Alexandra Hospital Research Ethics Committee.

Tissue collection

All duodenal biopsy specimens were obtained before phlebotomy was initiated in HHC subjects with significant iron overload who required treatment. Biopsies were collected from the second part of the duodenum, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C for total RNA extraction at a later date.

RNA preparation and ribonuclease protection assays

Total RNA was extracted from two pooled duodenal biopsies from each individual using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Melbourne, Australia) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Ribonuclease protection assays (RPAs) were performed on total RNA using riboprobes corresponding to the cDNA sequences (table 1 ▶). Riboprobe synthesis was performed using the appropriate linearised vector and the Riboprobe Combination System (SP6/T7 polymerase kit; Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) with minor modifications. Each transcription was carried out in a 20 μl reaction containing 40 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.9), 10 mM NaCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM each of rATP, rGTP, and rCTP, 17.5 μM cold rUTP, 1 μg vector DNA, 50μCi [α-32P]UTP (3000 Ci/mmol; NEN, Adelaide, Australia), 20 U RNasin, and 15–20 U T7 or SP6 RNA polymerase, as appropriate. The transcription reaction was incubated at 37°C for one hour before digestion with 1 U RQ1 RNase-Free DNase1 (Promega) for a further 15 minutes at 37°C. The riboprobes were electrophoresed on a 6% polyacrylamide, 50% urea gel for three hours at 200 V. Riboprobes visualised using autoradiography were excised and eluted for three hours at 37°C in 400 μl elution buffer (2 M ammonium acetate, 1% sodium dodecyl sulphate, 25 μg/ml yeast tRNA) before ethanol precipitation and resuspension in 50 μl of hybridisation buffer (40 mM PIPES, pH 6.4, 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 80% formamide).

Table 1.

cDNA sequences of riboprobes

| Size (nt) | cDNA sequence | GenBank accession No. | |

| DMT1 (non-IRE) | 273 | nt 1501–1773 | AF064484* |

| DMT1 (IRE) | 224 | ||

| Ireg1 | 173 | nt 1190–1362 | AF231121 |

| Hephaestin | 190 | nt 1207–1396 | AF148860 |

| Dcytb | 242 | nt 272–513 | XM015916 |

| GAPDH | 155 | nt 580–734 | M33197 |

*This riboprobe is based on the non-IRE splice variant but can also detect the iron responsive element (IRE) form as it crosses the splice site that distinguishes the two transcripts.

Dcytb, duodenal cytochrome-b; DMT1, divalent metal transporter 1; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3- phosphate dehydrogenase; Ireg1, iron regulated gene 1.

Human duodenal RNA samples (2 μg) were hybridised overnight at 45°C with 105cpm of all riboprobes. Following hybridisation, unprotected RNA was digested by addition of RNase digestion buffer (10 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA) containing 80 μg/ml of RNase A and 80 U/ml of RNase T1 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Castle Hill, Australia), and incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes. The reaction was extracted with 400 μl of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and the RNA-riboprobe hybrid precipitated with ethanol. Hybridised riboprobe samples were resolved on a 6% polyacrylamide, 50% urea gel for five hours at 200 V and detected after exposure for up to 96 hours at −70°C. The intensity of specific bands was determined by densitometry using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, California, USA). All RPAs were examined at different exposures and only those bands that lay within the linear range of the film were analysed. Expression of each of the iron transport genes was reported as a ratio of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) to correct for differences in total mRNA loading.

Statistical analysis

All patient demographic and laboratory data are expressed as mean (SD), except for SF which is presented as median (range). Duodenal levels of the iron transport genes were expressed as a ratio of GAPDH and reported as mean (SEM). SF and iron transport gene ratios showed a skewed distribution and were converted to logarithms before further statistical analysis. All statistical analyses, including the Student’s t test, analysis of variance, Pearson’s correlation, and regression analysis were performed on logarithmically transformed data. Comparisons between proportions were made by Pearson’s χ2 analysis. A p value of ⩽0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic and laboratory characteristics of the study population

Age and sex distributions, and laboratory characteristics of the 36 patients included in the study are shown in table 2 ▶. Sixteen of 36 patients were female. While the majority of iron deficient subjects were female, most HHC patients were male. Mean age of the HHC patients was significantly lower than subjects in the iron deficient and iron replete groups (p=0.05). There were significant differences in mean haemoglobin concentration, haematocrit, TS, and median SF between the three groups (p<0.001, p<0.001, p<0.001, and p<0.001, respectively).

Table 2.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the study population

| Haemochromatosis (n=12) | Iron deficient (n=11) |

Iron replete (n=13) |

p Value | |

| Sex (M:F) | 9:3 | 4:7 | 7:6 | 0.174 |

| Age (y) | 44.8 (15.9)* [17–69] | 60.1 (19.6) [19–80] | 57.4 (11.6) [39–77] | 0.05 |

| Hb (g/l) | 148.8 (14.3) | 106.2 (17.2)††† | 142.1 (11.6) | <0.001 |

| Hct (%) | 43.9 (3.9) | 33.6 (4.4)††† | 42.9 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| TS (%)‡‡‡ | 63.0 (16.0) | 6.7 (3.1) | 25.5 (8.6) | <0.001 |

| SF (μg/l)‡‡‡ | 900 (39–1806) | 13 (2–65) | 137 (31–244) | <0.001 |

Hb, haemoglobin; Hct, haematocrit; TS, transferrin saturation; SF, serum ferritin concentration.

Laboratory reference ranges for TS, SF, Hb, and Hct are 15–45%, 30–300 μg/l, 135–180 g/l, and 39–52%, respectively.

Data expressed as mean (SD) [range] or median (range).

Pearson’s χ2analysis was used to determine significant differences between groups for sex distribution. For all other variables, ANOVA was used to compare data between the three groups (right hand column) and the Student’s t test to compare data between two specific groups.

*p<0.05 for subjects with hereditary haemochromatosis (HHC) compared with iron deficient or iron replete subjects; †††p<0.001 for iron deficient subjects compared with HHC patients or iron replete subjects; ‡‡‡p<0.001 for HHC subjects compared with both other groups and iron deficient subjects compared with iron replete subjects.

All HHC patients had TS levels >40% but three subjects, all female, had normal SF values (39, 59, 65 μg/l). Two of these women were of child bearing age and still menstruating, and the third was aged 56 years with a history of eight pregnancies. The remaining nine subjects were male and all had SF values >504 μg/l. Of the six HHC patients who underwent liver biopsy, five subjects had minimal or no fibrosis and one subject had evolving cirrhosis. Three HHC subjects, all male, had a history of heavy alcohol consumption (>60 g/day) but only one had mild steatosis on liver biopsy. Another patient with a body mass index of greater than 30 kg/m2 but no history of alcohol consumption had severe steatosis. All six patients had grade 3 or 4 stainable liver iron and a hepatic iron concentration between 47 and 160 μmol/g dry weight.

Expression of DMT, Ireg1, hephaestin, and Dcytb

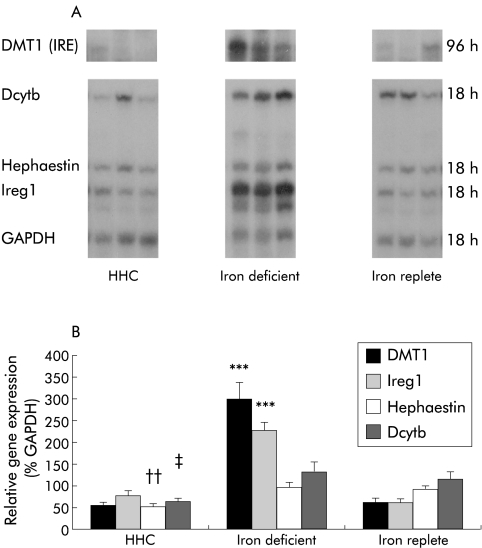

mRNA levels of the iron transport molecules were examined by RPA and assays of three representative patients from each group are shown in fig 1A ▶. Figure 1B ▶ shows mean levels for DMT1 (IRE), Ireg1, hephaestin, and Dcytb expressed as a percentage of the relative expression of GAPDH. There were significant differences in mean levels of DMT1 (IRE), Ireg1, and hephaestin between the three groups (p<0.001, p<0.001, and p=0.015, respectively) but there was no significant difference between the groups in Dcytb expression (p=0.12). Duodenal expression of DMT (IRE) and Ireg1 was similar in HHC patients and iron replete subjects (0.54 (0.07) v 0.59 (0.11), p=0.95; 0.78 (0.10) v 0.61 (0.07), p=0.25; respectively). In contrast, hephaestin expression in HHC subjects was approximately 60% of values in iron replete subjects and iron deficient subjects (0.53 (0.05) v 0.90 (0.09), p=0.02; v 0.96 (0.14), p=0.01; respectively). Similarly, expression of Dcytb was decreased in HHC patients compared with iron deficient patients (0.62 (0.08) v 1.32 (0.23); p=0.02) but not compared with iron replete subjects (1.12 (0.19); p=0.22).

Figure 1.

Duodenal expression of iron transport genes. (A) Ribo- nuclease protection assays of three representative patients from each of the hereditary haemochromatosis (HHC) (n=12), iron deficient (n=11), and iron replete (n=13) groups of patient. Total RNA was extracted from duodenal biopsies and gene expression determined by RPA using 2 μg of RNA. Gels were autoradiographed for varying times due to variations in the level of expression between the iron transport genes, and exposure times are indicated on the right. DMT1, divalent metal transporter 1; Dcytb, duodenal cytochrome-b; Ireg1, iron regulated gene 1; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (B) Relative gene intensities were estimated from densitometric scanning of autoradiographs. Values are expressed relative to GAPDH expression and are presented as mean (SEM). ***p<0.001 for DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 expression in iron deficient subjects compared with HHC patients or iron replete subjects; ††p<0.01 for hephaestin expression in HHC patients compared with iron deficient or iron replete subjects; ‡p<0.05 for Dcytb expression in HHC subjects compared with iron deficient patients.

Expression of DMT (IRE) and Ireg1 was increased 4–5-fold and 3–4-fold, respectively, in patients with iron deficiency compared with iron replete subjects (2.96 (0.38) v 0.59 (0.11), p<0.0001; 2.26 (0.18) v 0.61 (0.07), p<0.0001) (fig 1B ▶). In contrast, there were no significant differences in hephaestin or Dcytb expression in subjects with iron deficiency compared with iron replete subjects (0.96 (0.14) v 0.90 (0.09), p=0.76; 1.32 (0.23) v 1.12 (0.19), p=0.44, respectively). Expression of DMT1 (non-IRE) was extremely low in duodenal biopsies from all patients and did not contribute significantly to the level of total DMT1 present (data not shown).

Expression of DMT1 (IRE), Ireg1, hephaestin, and Dcytb in relation to serum iron indices and haematological parameters

In this series of untreated HHC patients, a strong inverse relationship between log SF and DMT1 (IRE) expression (r=−0.789, p=0.002) was found and a similar association was observed for Ireg1 (r=−0.621, p=0.03) but there was no significant correlation between TS, haemoglobin concentration, or haematocrit and duodenal iron transport gene expression (table 3 ▶). In non-HHC subjects, strong inverse correlations were found between DMT1 (IRE) expression and haemoglobin concentration (r=−0.680, p=0.0002), haematocrit (r=−0.677, p=0.003), log SF (r=−0.569, p=0.004), and TS (r=−0.677, p=0.003) (table 3 ▶). Similar results were observed for Ireg1 (table 3 ▶). There were no significant correlations between expression of hephaestin or Dcytb and serum iron indices or haematological parameters in any of the three groups.

Table 3.

Correlation between biochemical iron indices, haematological parameters, and expression of DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 in non-HHC subjects and patients with HFE related haemochromatosis

| Hb | Hct | Log SF | TS | |

| Non-HHC subjects (n=23) | ||||

| Log DMT1 (IRE) | ||||

| r | −0.680 | −0.677 | −0.569 | −0.677 |

| p | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| Log Ireg1 | ||||

| r | −0.589 | −0.574 | −0.541 | −0.667 |

| p | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.004 |

| HHC subjects (n=12) | ||||

| Log DMT1 (IRE) | ||||

| r | 0.069 | −0.244 | −0.798 | 0.049 |

| p | 0.820 | 0.450 | 0.002 | 0.881 |

| Log Ireg1 | ||||

| r | −0.270 | −0.432 | −0.620 | −0.102 |

| p | 0.390 | 0.171 | 0.030 | 0.760 |

Hb, haemoglobin concentration; Hct, haematocrit; TS, transferrin saturation; SF, serum ferritin concentration; HHC, hereditary haemochromatosis DMT1, divalent metal transporter 1; Ireg1, iron regulated gene 1.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to determine whether there was a linear relationship between gene expression of each iron transporter and TS, SF, Hb, or Hct.

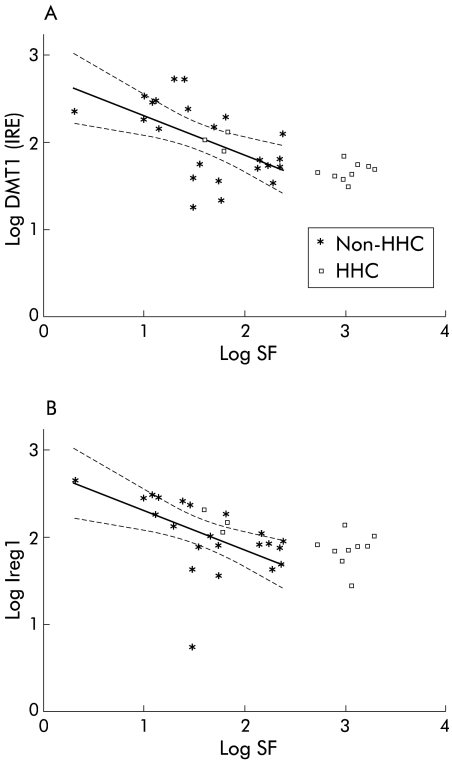

In order to determine if DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 expression were inappropriately increased in relation to body iron stores in HHC patients, the relationship between gene expression of these iron transporters and log SF was examined based on correlations observed in non-HHC patients (fig 2 ▶). Nine of 12 HHC patients lay outside and above the predicted linear extension of the regression lines for DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 based on non-HHC patients, suggesting that for a given SF, DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 levels were higher than predicted in HHC subjects with elevated SF. The three female HHC patients had appropriate levels of DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 expression for their SF.

Figure 2.

Association between serum ferritin concentration (SF) and gene expression of (A) divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1 (IRE)) and (B) iron regulated gene 1 (Ireg1) in hereditary haemochromatosis (HHC) and non-HHC patients. Correlation between log SF and DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 is shown for all study subjects (all single values). Regression lines (with 95% confidence intervals) are based on data from non-HHC patients only.

When all 36 subjects were analysed together, a significant positive correlation was found between expression of DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 (r=0.826, p<0.0001). This relationship was still present when HHC patients (r=0.754, p=0.005) and non-HHC patients were analysed separately (r=0.841, p<0.0001).

DISCUSSION

Recent identification of several molecules that play critical roles in iron transport across the duodenal enterocyte has greatly advanced our understanding of intestinal iron absorption. The potential roles of DMT1, Ireg1, hephaestin, and Dcytb in this pathway have been examined in animal models of disturbed iron metabolism but in relatively few human studies.

In this study, duodenal expression of DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 was similar in untreated HHC patients and iron replete subjects but in most of the HHC patients there appeared to an increase in DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 expression relative to SF. Furthermore, hephaestin and Dcytb were not upregulated in HHC and appear unlikely to play primary roles in the relative increase in iron absorption observed in HHC. As predicted, DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 expression was increased in iron deficient patients compared with iron replete subjects, thus acting as internal controls and confirming that the laboratory methods used in this study were appropriate. Significant positive correlations were present between DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 expression in all patient groups. There were significant inverse correlations between DMT (IRE) and Ireg1 and SF in HHC patients, suggesting that body iron stores still play a role in the regulation of duodenal expression of these iron transport genes. Expression of these iron transporters was assessed by RPAs only as recent studies indicate that protein levels parallel changes observed in gene expression of these molecules.15,16,21,29

Total body iron absorption may be normal12,23,24,30 or elevated only 2–3-fold in untreated HHC subjects10,31 compared with normal controls and this appears to be predominantly due to an increase in mucosal transfer and not to an increase in mucosal uptake of iron.10,12 Despite increased body iron stores, phlebotomy in HHC patients results in a further marked increase in total body iron absorption, indicating the importance of increased erythropoiesis and plasma iron turnover in the control of iron uptake and absorption.10,23,24,32 Iron absorption frequently remains elevated for a prolonged period after completion of venesection in HHC.10,23,24 In the original study of intestinal gene expression performed by Zoller et al, the 20 HHC subjects were a heterogenous group.20 The majority had completed treatment or were undergoing venesection at the time of the study and DMT1 expression was reported to be increased 100-fold.20 Similarly, in a recent study by Rolfs et al, five of nine subjects with HHC were fully treated and the remaining four subjects were being venesected.22 Venesection is likely to have contributed to the increase in DMT1 expression reported by Zoller20 and Rolfs22 and evidence for such an effect was provided in a subsequent study by Zoller et al who reported only a 2–10-fold increase in DMT1 and Ireg1 expression in eight untreated HHC patients with biochemical iron overload compared with normal controls.21 This marked variation in the reported increase in DMT1 expression in HHC patients and conflicting data on iron transporter expression in animal models of iron overload mandates the need for further studies of iron transporters in untreated human HHC patients.

In contrast with previous reports, an increase in the absolute level of DMT1 (IRE) or Ireg1 expression in untreated HHC patients was not demonstrated in this study. However, whether the level of expression of these iron transport genes was inappropriately high for the degree of iron loading warranted further consideration. SF, a laboratory indicator of body iron stores,33,34 was significantly associated with expression of both DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 in non-HHC subjects. Figure 2A ▶ and 2B ▶ show that all but three of the HHC patients lay beyond and above the regression lines relating SF and DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 levels in non-HHC subjects, suggesting that for a given SF, DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 levels were higher than predicted in most HHC subjects. For this comparison, we have assumed a linear relationship between SF and expression of these iron transport genes over all values of SF. These results support early HHC studies showing that although the absolute value of intestinal iron absorption is frequently not increased compared with normal controls, it is inappropriately increased in relation to their SF.12,30,31 Similarly, these findings are relevant in the context of previous studies investigating markers of intracellular iron status in duodenal tissue from patients with HHC. These studies showed that although the duodenal mucosal content of ferritin mRNA and protein is relatively low and the corresponding levels of transferrin receptor gene and protein expression are relatively high in patients with HHC,5–8 absolute levels were similar to those observed in normal control subjects.

Furthermore, in HHC patients there were significant linear relationships between SF and DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 expression. In addition, DMT1 (IRE) expression showed a positive correlation with Ireg1 expression in HHC and non-HHC patients. Iron absorption studies have shown a similar inverse relationship between SF and whole body iron absorption in subjects with HHC.12,30,31 Collectively, these results suggest that in HHC patients, changes in duodenal transport gene expression and consequently intestinal iron absorption are still subject to some regulation by body iron stores. In the current study, patient numbers were too small to examine the relationship between hepatic iron stores and duodenal expression of the iron transport genes.

Interestingly, three HHC patients had appropriate levels of DMT1 and Ireg1 for their SF. All three subjects were female with normal SF. It is interesting to speculate whether phenotypic non-expression in these three patients was a result of environmental factors or whether they have constitutively lower levels of expression of iron transporters. Further studies of intestinal iron transporters in non-expressing C282Y homozygous HHC patients would be of particular interest in determining the contributors to their attenuated phenotype.

Dietary factors may account in part for the difference in results between this study and that of Zoller and colleagues.21 Iron absorption is markedly influenced by recent dietary iron intake and studies conducted in rodents support a rapid regulatory effect of increased dietary non-haeme iron content resulting in decreased duodenal expression of iron transport genes.35,36 There are significant differences in the haem iron content of diets of different populations around the world. Australians and Americans consume a significantly greater amount of red meat in their diet than Europeans.37–40 It is well documented that red meat stimulates non-haem iron uptake but the mechanism is unknown.41–43 Ultimately it may be expected that this would result in a further increase in body iron stores and a relative downregulation of iron transport gene expression.

Human and animal studies support the existence of genes other than HFE that modify the HHC phenotype by influencing expression of iron transport molecules, and such genetic factors may provide a possible explanation for the differences in findings between different populations. In humans, for instance, the severity of iron loading and clinical disease is quite variable in patients with identical HFE genotypes, and in an Australian study examining disease expression in a large series of patients (and their relatives) referred for evaluation of iron overload, approximately one third of women and up to 10% of men homozygous for the C282Y mutation were non-expressers.44 Despite such variation, affected siblings have similar iron indices and several studies suggest that the ancestral haplotype is associated with more severe iron loading in HHC.45–47 There have been several recent population studies examining disease penetrance in HFE related HHC with marked variability in reported clinical expression of 1–50%.48–51 This is a controversial area and interpretation of the findings of these studies is difficult as they differ considerably in population selection and the use of controls. Furthermore, two groups have reported significant differences in duodenal expression of DMT1 in Hfe−/− mice of different genetic backgrounds.52,53 More recently, Dupic et al showed that differences in the severity of hepatic iron loading between Hfe−/− mice of two different strains were probably accounted for by variations in expression of DMT1, Ireg1, and Dcytb.54

There are no prior data on Dcytb protein or gene levels in human subjects with iron deficiency or HHC. In this study, Dcytb levels were similar in iron deficient patients and iron replete subjects. However, in hpx−/− mice, duodenal Dcytb mRNA and protein levels increased in response to iron deficiency and anaemia.15 Studies from our group showed regulation of Dcytb mRNA levels by changes in dietary iron content and body iron status in rodents.29 However, the mechanism by which iron regulates Dcytb expression is still unclear as Dcytb is reported not to possess an IRE. Expression of Dcytb was not increased in HHC subjects, suggesting that it does not play a primary role in the increased iron absorption characteristic of HHC. In vitro studies examining mucosal surface ferric iron reducing activity in duodenal fragments taken from untreated and treated patients with HHC have shown a significant increase in duodenal ferric iron reduction and increased iron uptake compared with normal controls.55 However, in Hfe−/− mice, Griffith et al showed no difference in duodenal ferrireductase activity between Hfe−/− and wild-type animals.56 More recently, Dupic et al showed that Dcytb follows a similar expression pattern to that of DMT1 and Ireg1, with marked differences observed between Hfe knockout mice of different genetic backgrounds.54 The role of Dcytb in the adaptive response to iron deficiency in humans remains to be clarified and further studies are needed to determine the precise function of Dcytb in iron absorption and the mechanism of its regulation by iron.

Expression of hephaestin was decreased in subjects with HHC compared with iron replete and iron deficient subjects but levels of hephaestin were similar in iron deficient and iron replete subjects. It is unlikely that the decrease in hephaestin levels is of physiological significance as the difference was less than twofold in magnitude. These results, together with those of Rolfs and colleagues,22 suggest that changes in hephaestin expression cannot account for the increased iron absorption characteristic of HHC. Duodenal expression of DMT (non-IRE) was negligible and there were no observable differences in expression between the three groups. From these results and those of others,22 it appears unlikely that DMT1 (non-IRE) plays a major role in the changes observed in duodenal DMT1 gene levels.

In summary, this study supports the primary roles of DMT1 and Ireg1 in mediating increased iron absorption in human subjects with iron deficiency. Duodenal expression of these iron transport genes was inversely regulated by body iron stores in iron deficient and iron replete subjects. Although we did not find an absolute increase in expression of DMT1 (IRE) or Ireg1 in a group of untreated C282Y homozygous HHC patients, there appears to be a relative increase in the levels of these iron transport genes for any given serum ferritin concentration in most HHC patients. In these patients, DMT1 (IRE) and Ireg1 levels were inversely proportional to serum ferritin concentration, suggesting that body iron stores still have some regulatory effect on expression of these iron transport genes in HHC.

Acknowledgments

KAS is a recipient of a National Health and Medical Research Council Postgraduate Medical Scholarship. LMF and DHC are affiliated with the University of Queensland. This study was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Queensland Liver Transplant Service, and the Princess Alexandra Hospital Research and Development Foundation. The authors wish to thank Dr David Purdie, biomedical statistician from the Queensland Institute of Medical Research, for his statistical advice and assistance.

Abbreviations

Dcytb, duodenal cytochrome-b

DMT1, divalent metal transporter 1

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

HHC, hereditary haemochromatosis

IRE, iron responsive element

Ireg1, iron regulated gene 1

RPA, ribonuclease protection assay

SF, serum ferritin concentration

TS, transferrin saturation

UTR, untranslated region

REFERENCES

- 1.Crawford DH, Leggett BA, Powell LW. Haemochromatosis. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol 1998;12:209–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feder JN, Gnirke A, Thomas W, et al. A novel MHC class I-like gene is mutated in patients with hereditary haemochromatosis. Nat Genet 1996;13:399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jouanolle AM, Gandon G, Jezequel P, et al. Haemochromatosis and HLA-H. Nat Genet 1996;14:251–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jazwinska EC, Cullen LM, Busfield F, et al. Haemochromatosis and HLA-H. Nat Genet 1996;14:249–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pietrangelo A, Casalgrandi G, Quaglino D, et al. Duodenal ferritin synthesis in genetic hemochromatosis. Gastroenterology 1995;108:208–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pietrangelo A, Rocchi E, Casalgrandi G, et al. Regulation of transferrin, transferrin receptor, and ferritin genes in human duodenum. Gastroenterology 1992;102:802–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whittaker P, Skikne BS, Covell AM, et al. Duodenal iron proteins in idiopathic hemochromatosis. J Clin Invest 1989;83:261–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banerjee D, Flanagan PR, Cluett J, et al. Transferrin receptors in the human gastrointestinal tract. Relationship to body iron stores. Gastroenterology 1986;91:861–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrews NC. Disorders of iron metabolism. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1986–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powell LW, Campbell CB, Wilson E. Intestinal mucosal uptake of iron and iron retention in idiopathic haemochromatosis as evidence for a mucosal abnormality. Gut 1970;11:727–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson GJ, Vulpe CD. Regulation of intestinal iron transport. In: Templeton DM, ed. Molecular and Cellular Iron Transport. New York: Marcel Dekker, 2002:560–99.

- 12.McLaren GD, Nathanson MH, Jacobs A, et al. Regulation of intestinal iron absorption and mucosal iron kinetics in hereditary hemochromatosis. J Lab Clin Med 1991;117:390–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleming MD, Trenor CC, Su MA, et al. Microcytic anaemia mice have a mutation in Nramp2, a candidate iron transporter gene. Nat Genet 1997;16:383–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunshin H, Mackenzie B, Berger UV, et al. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter. Nature 1997;388:482–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKie AT, Barrow D, Latunde-Dada GO, et al. An iron-regulated ferric reductase associated with the absorption of dietary iron. Science 2001;291:1755–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKie AT, Marciani P, Rolfs A, et al. A novel duodenal iron-regulated transporter, IREG1, implicated in the basolateral transfer of iron to the circulation. Mol Cell 2000;5:299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donovan A, Brownlie A, Zhou Y, et al. Positional cloning of zebrafish ferroportin1 identifies a conserved vertebrate iron exporter. Nature 2000;403:776–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abboud S, Haile DJ. A novel mammalian iron-regulated protein involved in intracellular iron metabolism. J Biol Chem 2000;275:19906–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vulpe CD, Kuo YM, Murphy TL, et al. Hephaestin, a ceruloplasmin homologue implicated in intestinal iron transport, is defective in the sla mouse. Nat Genet 1999;21:195–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zoller H, Pietrangelo A, Vogel W, et al. Duodenal metal-transporter (DMT-1, NRAMP-2) expression in patients with hereditary haemochromatosis. Lancet 1999;353:2120–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zoller H, Koch RO, Theurl I, et al. Expression of the duodenal iron transporters divalent-metal transporter 1 and ferroportin 1 in iron deficiency and iron overload. Gastroenterology 2001;120:1412–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rolfs A, Bonkovsky HL, Kohlroser JG, et al. Intestinal expression of genes involved in iron absorption in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2002;282:G598–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith PM, Godfrey BE, Williams R. Iron absorption in idiopathic haemochromatosis and its measurement using a whole-body counter. Clin Sci 1969;37:519–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams R, Manenti F, Williams HS, et al. Iron absorption in idiopathic haemochromatosis before, during, and after venesection therapy. BMJ 1966;2:78–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCullen MA, Crawford DH, Dimeski G, et al. Why there is discordance in reported decision thresholds for transferrin saturation when screening for hereditary hemochromatosis. Hepatology 2000;32:1410–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guyader D, Jacquelinet C, Moirand R, et al. Noninvasive prediction of fibrosis in C282Y homozygous hemochromatosis. Gastroenterology 1998;115:929–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Searle JA, Kerr JFR, Halliday JW, et al. Iron storage disease. In: MacSween RNM, Anthony PP, Scheuer PJ, et al, eds. Pathology of the Liver, 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1994:219–41.

- 28.Torrance JD, Bothwell TH. A simple technique for measuring storage iron concentrations in formalinised liver samples. S Afr J Med Sci 1968;33:9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frazer DM, Wilkins SJ, Becker EM, et al. Hepcidin expression inversely correlates with expression of duodenal iron transporters and iron absorption in rats. Gastroenterology 2002;123:835–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lynch SR, Skikne BS, Cook JD. Food iron absorption in idiopathic hemochromatosis. Blood 1989;74:2187–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walters GO, Jacobs A, Worwood M, et al. Iron absorption in normal subjects and patients with idiopathic haemochromatosis: relationship with serum ferritin concentration. Gut 1975;16:188–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weintraub LR, Conrad ME, Crosby WH. The treatment of hemochromatosis by phlebotomy. Med Clin North Am 1966;50:1579–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cook JD, Lipschitz DA, Miles LE, et al. Serum ferritin as a measure of iron stores in normal subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 1974;27:681–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bezwoda WR, Bothwell TH, Torrance JD, et al. The relationship between marrow iron stores, plasma ferritin concentrations and iron absorption. Scand J Haematol 1979;22:113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oates PS, Jeffrey GP, Basclain KA, et al. Iron excretion in iron-overloaded rats following the change from an iron-loaded to an iron-deficient diet. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;15:665–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeh KY, Yeh M, Watkins JA, et al. Dietary iron induces rapid changes in rat intestinal divalent metal transporter expression. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2000;279:G1070–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Nutrition Survey. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1995.

- 38.Food and Nutrition Information Centre, National Agricultural Library, USA. Food Consumption, Prices and Expenditure (1970–1997). Ithaca, New York: United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- 39.Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, United Kingdom. National Food Survey (1974–2000). London: Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food, 2000.

- 40.Osterreichisches Statistisches Zentralamt (1998). Austria: Eurofood, 1999.

- 41.Cook JD, Monsen ER. Food iron absorption in human subjects. III. Comparison of the effect of animal proteins on non-heme iron absorption. Am J Clin Nutr 1976;29:859–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bjorn-Rasmussen E, Hallberg L. Effect of animal proteins on the absorption of food iron in man. Nutr Metab 1979;23:192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Engelmann MD, Davidsson L, Sandstrom B, et al. The influence of meat on non-heme iron absorption in infants. Pediatr Res 1998;43:768–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crawford DH, Jazwinska EC, Cullen LM, et al. Expression of HLA-linked hemochromatosis in subjects homozygous or heterozygous for the C282Y mutation. Gastroenterology 1998;114:1003–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crawford DH, Powell LW, Leggett BA, et al. Evidence that the ancestral haplotype in Australian hemochromatosis patients may be associated with a common mutation in the gene. Am J Hum Genet 1995;57:362–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pratiwi R, Fletcher LM, Pyper WR, et al. Linkage disequilibrium analysis in Australian haemochromatosis patients indicates bipartite association with clinical expression. J Hepatol 1999;31:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piperno A, Arosio C, Fargion S, et al. The ancestral hemochromatosis haplotype is associated with a severe phenotype expression in Italian patients. Hepatology 1996;24:43–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olynyk JK, Cullen DJ, Sina Aquilia BS et al. A population-based study of the clinical expression of the hemochromatosis gene. N Engl J Med 1999;341:718–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beutler E, Felitti VJ, Koziol JA, et al. Penetrance of 845G→A (C282Y) HFE hereditary haemochromatosis mutation in the USA. Lancet 2002;359:211–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Asberg A, Hveem K, Thorstensen K, et al. Screening for hemochromatosis: high prevalence and low morbidity in an unselected population of 65,238 persons. Scand J Gastroenterol 2001;36:1108–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jackson HA, Carter K, Darke C, et al. HFE mutations, iron deficiency and overload in 10 500 blood donors. Br J Haematol 2001;114:474–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fleming RE, Migas MC, Zhou X, et al. Mechanism of increased iron absorption in murine model of hereditary hemochromatosis: increased duodenal expression of the iron transporter DMT1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:3143–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Canonne-Hergaux F, Levy JE, Fleming MD, et al. Expression of the DMT1 (NRAMP2/DCT1) iron transporter in mice with genetic iron overload disorders. Blood 2001;97:1138–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dupic F, Fruchon S, Bensaid M, et al. Inactivation of the hemochromatosis gene differentially regulates duodenal expression of iron-related mRNAs between mouse strains. Gastroenterology 2002;122:745–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raja KB, Pountney D, Bomford A, et al. A duodenal mucosal abnormality in the reduction of Fe(III) in patients with genetic haemochromatosis. Gut 1996;38:765–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Griffiths WJ, Sly WS, Cox TM. Intestinal iron uptake determined by divalent metal transporter is enhanced in HFE-deficient mice with hemochromatosis. Gastroenterology 2001;120:1420–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]