Abstract

Background and aim: The role of transforming growth factor β-1 (TGFβ-1) in neuroendocrine tumour biology is currently unknown. We therefore examined the expression and biological significance of TGFβ signalling components in neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) of the gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) tract.

Methods: Expression of TGFβ-1 and its receptors, Smads and Smad regulated proteins, was examined in surgically resected NET specimens and human NET cell lines by immunohistochemistry, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction, immunoblotting, and ELISA. Activation of TGFβ-1 dependent promoters was tested by transactivation assays. Growth regulation was evaluated by cell numbers, soft agar assays, and cell cycle analysis using flow cytometry. The role of endogenous TGFβ was assessed by a TGFβ neutralising antibody and stable transfection of a dominant negative TGFβR II receptor construct.

Results: Coexpression of TGFβ-1 and its receptors TGFβR I and TGFβR II was detected in 67% of human NETs and in all three NET cell lines examined. NET cell lines expressed the TGFβ signal transducers Smad 2, 3, and 4. In two of the three cell lines, TGFβ-1 treatment resulted in transactivation of a TGFβ responsive reporter construct as well as inhibition of c-myc and induction of p21(WAF1) expression. TGFβ-1 inhibited anchorage dependent and independent growth in a time and dose dependent manner in TGFβ-1 responsive cell lines. TGFβ-1 mediated growth inhibition was due to G1 arrest without evidence of induction of apoptosis. Functional inactivation of endogenous TGFβ revealed the existence of an autocrine antiproliferative loop in NET cells.

Conclusions: Neuroendocrine tumour cells of the gastroenteropancreatic tract are subject to paracrine and autocrine growth inhibition by TGFβ-1, which may account in part for the low proliferative index of this tumour entity.

Keywords: transforming growth factor beta, neuroendocrine tumour, enteroendocrine cells, Smad3

Neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) of the gastroenteropancreatic tract (GEP) are rare and originate from a pluripotent stem cell of the diffuse endocrine system of the pancreas and gut.1 They are classified according to their ontogenetic origin into fore, mid, and hindgut NETs.2 GEP-NETs are predominantly slow progressing and may grow for months to years without overt clinical symptoms. Based on their characteristic tumour biological phenotype, they have also been referred to as “cancer in slow motion”.3

The molecular mechanisms responsible for the slowly proliferating phenotype of NETs are poorly understood. To date, genetic analysis of NETs has not revealed a particular difference from other rapidly growing gastrointestinal tumours4 which could account for this phenomenon. It therefore appears likely that growth factors or cytokines may be involved in growth regulation of NET cells.

In this context, several growth factors and cytokines are secreted by NET cells, including transforming growth factor β (TGFβ).5 The TGFβ family consists of three members (TGFβ1–3) which act as multifunctional proteins regulating growth and differentiation of various cell types.6 TGFβ-1 elicits its biological response after binding to the type II receptor (TGFβR II) which results in heterodimerisation with the type I receptor (TGFβR I) and its subsequent phosphorylation. Activation of TGFβR I results in phosphorylation of the receptor associated Smad proteins 2 and/or 3 which then form heterodimeric complexes with Smad 4. The Smad complexes are translocated into the nucleus where they operate as transcription factors interacting with TGFβ responsive promoters and cooperate with general transcription factors to regulate transcription of target genes.6,7

One central biological response to TGFβ-1 stimulation is growth inhibition which is due to either G1 cell cycle arrest or induction of apoptosis.8 This physiological growth restraint by TGFβ-1 is often lost during malignant transformation which might contribute to the malignant phenotype of various cancers.9 The molecular alterations associated with loss of physiological TGFβ responsiveness on carcinogenesis comprise an elevated expression of TGFβ-1, somatic mutations of the TGFβR II as well as TGFβR I, and loss of function mutations of the Smad genes.10,11 All inactivating mutations or loss of expression of the TGFβ signalling pathway components can result in resistance to TGFβ-1 growth inhibition. Currently, we know very little about the expression of the TGFβ/TGFβ receptor system in human NET cells. The current study was therefore designed to investigate the expression and biological relevance of TGFβ signalling components in GEP-NET cells.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Materials

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, RPMI 1640 medium, and phosphate buffered saline (PBS) were purchased from Gibco BRL (Berlin, Germany), and UltraCulture medium from Bio Whittaker (Verviers, Belgium). Fetal calf serum, trypsin/EDTA, and penicillin/streptomycin were from Biochrom (Berlin, Germany). Recombinant human TGFβ-1, TGFβ-2, TGFβ-3, human TGFβ-1 immunoassay, and pan-specific TGFβ antibody (neutralising the biological activity of TGFβ) were from R&D systems (Wiesbaden, Germany). The following antibodies were purchased: anti-poly(ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP) antibody from Calbiochem/Oncogene Research (Bad Soden, Germany); c-myc and Smad 2/3 from BD PharMingen (Heidelberg, Germany); Smad 4/DPC4 and Smad3 from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, USA); proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), TGFβ-1 (does not cross react with TGFβ-2 and TGFβ-3), TGFβR I, and TGFβR II from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, USA), and secondary antibodies from Dianova (Hamburg, Germany). The chemiluminescence immunoassay for quantification of cell proliferation, based on measurement of BrdU incorporation during DNA synthesis, was from Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany). Reagents for western blotting were purchased from BioRad Laboratories (Munich, Germany), and enhanced chemiluminescence and polyvinyl difluoride membranes from NEN (Köln, Germany). Superscript reverse transcriptase and oligo(d)T were purchased from GibcoBRL (Eggenstein, Germany); all PCR reagents were from Roche (Mannheim, Germany).

Immunohistochemistry

For our immunohistochemical studies, we used archival tumour material from NET patients resected at Charité University Hospital. All patients gave written informed consent prior to the operation. Tissue sections of resected NETs were formalin fixed and embedded in paraffin. Endogenous peroxidase and non-specific binding were blocked and samples were boiled for 20 minutes in citrate buffer (0.01 M citrate, pH 6,0) to expose the epitopes. Specimens were incubated with antibodies (all antibodies were diluted in PBS with 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.5% Tween 20) directed against TGFβ-1 (1:100), TGFβR I (1:100), TGFβR II (1:50), or synaptophysin (1:200). For these experiments, we used a monospecific antibody against TGFβ-1, which does not cross react with TGFβ-2 or TGFβ-3. Two independent approaches were used to confirm specificity of the observed immunohistochemical staining (serial dilution until signal disappeared and preimmune serum as first antibody which failed to reveal staining).

Immunohistochemical staining was performed according to the peroxidase method using a horseradish peroxidase coupled secondary antibody and 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole as the chromogen (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California, USA). Immunostaining was defined as positive when at least 10% of tumour cells showed specific immunoreactivity.

Cell culture

The following human NET cell lines were used and cultured as previously described: BON cells derived from a human functional neuroendocrine pancreatic tumour, LCC-18 cells derived from a non-functional neuroendocrine colorectal tumour, and QGP cells derived from a non-functional neuroendocrine pancreatic tumour.12 The human pancreatic carcinoma cell lines BxPc3 and PANC-1 were obtained from the American Type Tissue Culture Collection (Manassas, Virginia, USA). All media contained 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin and 2 mM l-glutamine. Cells were maintained in 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C.

RNA preparation and RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from all cell lines using RNAzol B reagent (WAK Chemie, Bad Soden, Germany), as described in the supplier’s manual. cDNA synthesis was performed at 37°C for 120 minutes in a volume of 30 μl containing 1 μg total RNA and Oligo(d)T as primer using superscript reverse transcriptase. Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed in a volume of 50 μl using 1 μl of the first strand cDNA, 0.1 μg of each primer (forward and reverse), 1.25 μM of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate (dNTP), 1×PCR buffer containing MgCl2, and 1 U of Taq-polymerase. The following primers were designed complementary to the published nucleotide sequence: GAPDH forward (5′-TTC-TTT-TGC-GTC-GCC-AGC-CG-3′); GAPDH reverse (5′-CAA-ATG-AGC-CCC-AGC-CTT-CTC-C-3′); TGFβR I forward (5′-AAC-CGC-ACT-GTC-ATT-CAC-3′); TGFβR I reverse (5′-TTC-CTC-TCC-AAA-CTT-CTC-C-3′); TGFβR II forward (5′-ATG-GAG-TTC-AGC-GAG-CAC-3′); TGFβR II reverse (5′-CAC-AGG-CAG-CAG-GTT-AGG-3′); TGFβ-2 forward (5′-CCC-CAG-AAG-ACT-ATC-CTG-A-3′); TGFβ-2 reverse (5′-GCG-GCA-TGT-CTA-TTT-TGT-3′); TGFβ-3 forward (5′-GTG-AGT-GGC-TGT-TGA-GAA-3′); and TGFβ-3 reverse (5′-AGA-TGA-GGG-TTG-TGG-TGA-3′).

PCR conditions comprised a denaturing step at 94°C for five minutes, an annealing step at 63°C (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)), 55°C (TGFβ-3), 58°C (TGFβR I and TGFβ-2), or 61°C (TGFβR II) for one minute, and an extension step at 72°C for two minutes for one cycle, followed by 21 cycles (GAPDH), 29 cycles (TGFβR I and TGFβR II), 35 cycles (TGFβ-3), or 38 cycles (TGFβ-2) at 94°C for one minute, 63°C, 55°C, 58°C, or 61°C for one minute, and 72°C for two minutes. The reaction (10 μl) was electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels.

Protein extraction and western blotting

Whole cell extracts were obtained from subconfluently growing cells, and lysed with 1×RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5; 0.15 M NaCl; 0.25% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS); 0.05% desoxycholate; 1% IGEPAL; 1 mM dithiothreitol; 3 mg/ml aprotinin; 2 mM leupeptin; 10 μM E64). Lysates were harvested, genomic DNA was fragmented, and lysates were incubated for one hour on ice before centrifugation. Supernatants were quantified by a Lowry based assay and equal amounts of each extract were applied to SDS gels. After electrophoresis, SDS gels were transferred to polyvinyl difluoride membranes. Blots were reacted overnight at 4°C with the respective monospecific antibodies (diluted 1:1000 in 5% non-fat dried milk in 1×PBS with 0.5% Tween). Immunoreactive bands were identified using peroxidase coupled antirabbit or antimouse antibodies and visualised by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham) and exposed to x ray films (Kodak, Stuttgart, Germany).

Transient transfection assays

BON cells (2×105), LCC-18 cells (4×105), or QGP cells (1×105) were attached overnight and then transfected with 0.4 μg of the TGFβ sensitive p3TPlux luciferase reporter construct (kindly provided by Jeff Wrana, Toronto, Canada13) and 0.01 μg of renilla control reporter construct pRL-TK (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) for four hours with 10 μl Effectene (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the supplier’s manual. After washing with 1×PBS, cells were recultured in UltraCulture medium for 24 hours under standard conditions in the presence or absence of 10 ng/ml TGFβ-1. Cell extracts were then prepared using the dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Mannheim, Germany). Firefly luciferase and renilla luciferase luminescence were determined using 25 μl of cell lysate and measured for 15 seconds using a Lumat LB 9501 (EG&G Berthold, Bad Wildbach, Germany). Results were normalised to renilla luciferase light production to correct for transfection efficiency.

Growth assays

Cells were plated in 24 well culture dishes at a density of 1.5×104 cells/well and allowed to attach overnight. Medium was then replaced either with or without TGFβ-1 or neutralising TGFβ antibody. At the indicated time points, cells were washed with 1×PBS and harvested by trypsinisation. The number of cells was measured using a Coulter Counter (Beckman, Krefeld, Germany). All growth kinetics were performed with a minimum of three values for each time point and repeated in triplicate.

Cell proliferation was also assayed by a chemiluminescence immunoassay measuring BrdU incorporation during DNA synthesis: 5×103 cells/well were seeded in a 96 well microtitre plate and allowed to attach overnight. TGFβ-1 or neutralising TGFβ antibody was added and incubated for 72 hours. For the last six hours BrdU was added to the cells. After harvesting the microtitre plate, cells were fixed and DNA was denatured. An anti-BrdU antibody was incubated, binding to the BrdU incorporated in newly synthesised cellular DNA. The immune complexes were detected by the subsequent substrate reaction and chemiluminescence detection was performed using a Microlumat Plus LB 96V (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbach, Germany).

Anchorage independent growth

Clonal growth of NET cells was examined based on colony formation in agar suspension, as previously described.12 In brief, 103 cells were plated as a single cell suspension in methylcellulose and incubated over 10 days. Colonies were scored microscopially with an arbitrary cut off set at 30 cells minimum.

Flow cytometry

NET cells were fixed with 70% ethanol at −20°C overnight, washed with 1×PBS, and stained with propidium iodide (50 μg/ml) in 1×PBS supplemented with RNase (10 mg/ml) for 30 minutes. Flow cytometry was performed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) equipped with Cellquest software, and cellular DNA content was determined for 1×104 cells.

Measurement of TGFβ-1 in cell cultures

TGFβ-1 concentrations were assayed by a specific human TGFβ-1 Elisa (R&D Systems) following the manufacturer’s instructions and normalised to protein content.

Stable transfection of dominant negative TGFβR II

BON cells were transfected using the Effectene reagent following the manufacturer’s instructions. The expression vector contained a cDNA construct encoding a dominant negative mutant of the TGFβR II fused to enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) (TβRII-KR/EGFP) or an empty EGFP expression vector as a control (pEGFP-N3) (kindly provided by JY Li, France). TβRII-KR contains the human TGFβR II cDNA mutated (K277R at position 1167) and deleted for the last 639 bp of its coding region which was inserted into the pEGFP-N3 expression vector upstream and in frame with the EGFP encoding sequence.14 Transfected cells were kept under G418 selection pressure and expanded. Successful transfection was confirmed by western blotting using an anti-GFP antibody and fluorescence microscopy.

Statistical analysis

All data are shown as mean (SEM) unless otherwise indicated. Statistically significant differences were evaluated by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad statistical software (San Diego, California, USA). Differences were considered statistically different at a p value of <0.05.

RESULTS

Expression of TGFβ-1 and its receptors in human NETs

Twelve NET samples including five cases from the foregut, four cases from the midgut, and three cases from the hindgut were examined by immunohistochemistry using rabbit monospecific antibodies against synaptophysin, TGFβ-1, TGFβR I, and TGFβR II.

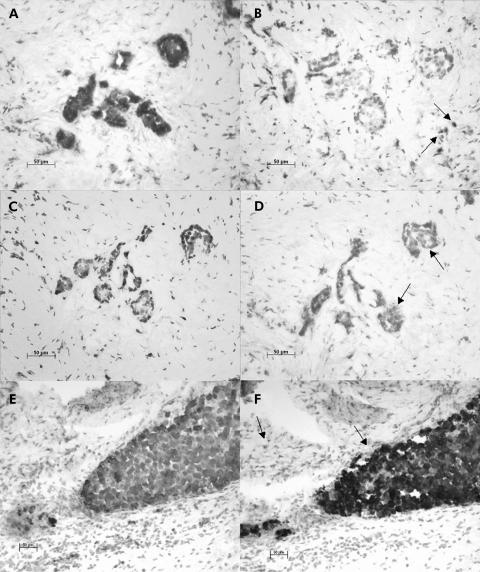

As expected, synaptophysin, which serves as a marker for neuroendocrine differentiation,1 stained tumour cells positive in all samples investigated. (fig 1A, C, E ▶).

Figure 1.

Expression of transforming growth factor β-1 (TGFβ-1) in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (NETs). Immunostaining with anti-synaptophysin antibody (A, C, E) and anti-TGFβ-1 antibody (B, D, F). Representative results of 12 tumour samples analysed. TGFβ-1 was detected in tumour cells (D, arrows), mesenchyme (B, arrows), or in both cell types (F, arrows), as derived from serial sections stained with synaptophysin to detect NET cells. Original magnifications ×20.

Analysis of TGFβ-1 expression revealed eight immunoreactive tumours (corresponding to 66.7% of all; 4/5 foregut (80%), 2/4 midgut (50%), 2/3 hindgut (66.7%)) (fig 1D, F ▶, table 1 ▶) and four non-reactive tumours (fig 1B ▶). Expression of TGFβ-1 in the surrounding mesenchymal tissue was detectable in eight samples (corresponding to 66.7% of all; 3/5 foregut (60%), 4/4 midgut (100%), 1/3 hindgut (33.3%)) (fig 1B, F ▶); coexpression of TGFβ-1 in both tumour and mesenchyme was detected in five samples (corresponding to 62.5% of all; 2/5 foregut (40%), 2/4 midgut (50%), 1/3 hindgut (33.3%)) (fig 1F ▶). When more demanding criteria were applied (for example, 25% and 50% of all tumour cells stained positive), we still observed 50% and 33% TGFβ-1 positive tumours, respectively.

Table 1.

Expression of transforming growth factor β-1 (TGFβ) and its receptors TGFβR I and TGFβR II in human neuroendocrine tumours (NET)

| TGFβ | TGFβR I | TGFβR II | |||||||||

| Patient No | Sex | NET | Tumour origin | Synaptophysin | T | M | T | M | T | M | Ki-67 (%) |

| 1 | M | Foregut | Pancreas | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | <1 |

| 2 | F | Foregut | Jejunum | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | <1 |

| 3 | M | Foregut | Pancreas | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | <1 |

| 4 | M | Foregut | Pancreas | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | 5 |

| 5 | F | Foregut | Pancreas | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | na |

| 6 | M | Midgut | Caecum | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | 10 |

| 7 | M | Midgut | Caecum | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| 8 | F | Midgut | Appendix | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | <1 |

| 9 | M | Midgut | Caecum | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | 5 |

| 10 | M | Hindgut | Sigma | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | 70 |

| 11 | M | Hindgut | Sigma | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 40 |

| 12 | M | Hindgut | Rectum | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 80 |

+, positive signal; −, no signal; T, tumour; M, mesenchyme; na, not available.

Ki-67 proliferation index, as detected by immunohistochemistry.

Likewise, we investigated expression of the two TGFβ-1 receptors, TGFβR I and TGFβR II, in the same tumour samples. Tumour cell expression of both receptors was observed in all 12 tumours, indicating that coexpression of TGFβ-1 and its receptors was a common feature for the majority of NET cells examined (8/12 tumours; 66.7% of all) (table 1 ▶). Expression of the two TGFβ-1 receptors was also detectable in the surrounding mesenchyme in 6/12 samples for TGFβR I and in 3/12 cases for TGFβR II; furthermore, five tumour samples demonstrated coexpression of TGFβR I and TGFβR II in the surrounding mesenchyme. It is noteworthy that the surrounding tumour mesenchyme also demonstrated coexpression of TGFβ-1 and its receptors TGFβR I and TGFβR II in 3/12 cases (25%) (table 1 ▶).

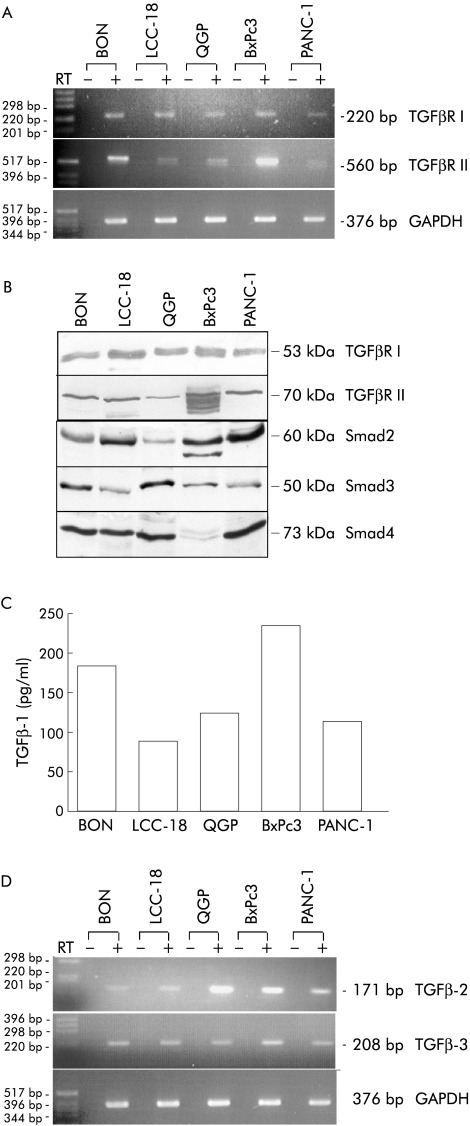

Expression of TGFβ signalling components in human NET cell lines

We next attempted to identify representative human neuroendocrine cell lines as a suitable in vitro model to study the biological effects of TGFβ-1. For this purpose we used the human neuroendocrine cell lines BON, LCC-18, and QGP. The exocrine pancreatic cancer cell lines BxPc3 and PANC-1, which have previously been characterised as TGFβ-1 sensitive,15 were used as positive controls. By RT-PCR, we were able to detect mRNA expression of TGFβR I and TGFβR II in all (5/5) cell lines (fig 2A ▶).

Figure 2.

Expression of transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signalling components in neuroendocrine tumour (NET) cell lines. (A) NET cell lines express TGFβ type I receptor (TGFβR I) and TGFβ type II receptor (TGFβR II) mRNA transcripts. RT-PCR analysis using primers specifically directed against TGFβR I, TGFβR II, and GAPDH was performed. Alternating lanes represent the results with (+) or without (−) prior reverse transcription to exclude genomic DNA contamination. A 100 bp DNA standard was used for size determination and the size of the amplicons are indicated. (B) Immunoblots using whole cell extracts (50 μg protein/lane) were performed to determine expression of TGFβR I, TGFβR II, Smad2, Smad3, and Smad4 protein. Immunodetectable proteins migrated at the expected molecular mass, as indicated. (C) TGFβ-1 protein is expressed and secreted in NET cell lines. Cells (2×104) were seeded overnight and cultured in serum free UltraCulture medium for three days. A TGFβ-1 specific ELISA was used to determine TGFβ-1 concentrations in the supernatants of the indicated cell lines and normalised to protein content/ml supernatant. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. (D) NET cell lines express TGFβ-2 and TGFβ-3 mRNA transcripts. RT-PCR analysis using primers specifically directed against TGFβ-2 and TGFβ-3 was performed. Alternating lanes represent the results with (+) or without (−) prior reverse transcription.

Western blot analyses of whole cell extracts revealed expression of the respective receptor proteins. We detected TGFβR I (53 kDa) and TGFβR II (70 kDa) in all cell lines (5/5), thereby confirming the results obtained by RT-PCR (fig 2B ▶).

We next investigated expression of the Smad proteins which act as TGFβ-1 downstream effectors. Analysis of whole cell extracts demonstrated Smad2 in all investigated cell lines. The Smad3 antibody detected a protein migrating at the expected size of approximately 50 kDa in all cell lines and the Smad4 antiserum detected a band at the expected size of 73 kDa in all neuroendocrine cell lines (3/3) and PANC-1 cells. In contrast, no Smad4 protein was detected in BxPc3 cells, which were previously described as devoid of Smad4 expression16 (fig 2B ▶). We next evaluated synthesis and secretion of TGFβ-1 by analysing conditioned supernatant from all cell lines using a human TGFβ-1 specific ELISA. Considerable amounts of TGFβ-1 were detectable in supernatants of all five cell lines investigated (fig 2C ▶), albeit in various concentrations, varying from 87.9 pg/ml (LCC-18) to 235.5 pg/ml (BxPc3). By RT-PCR analysis we were also able to detect TGFβ-2 and TGFβ-3 mRNA expression in all three NET cell lines (fig 2D ▶). These data suggest that the NET cell lines reflect the majority of human NETs in vivo with respect to coexpression of TGFβ-1 and its receptors.

TGFβ-1 signalling in NET cell lines

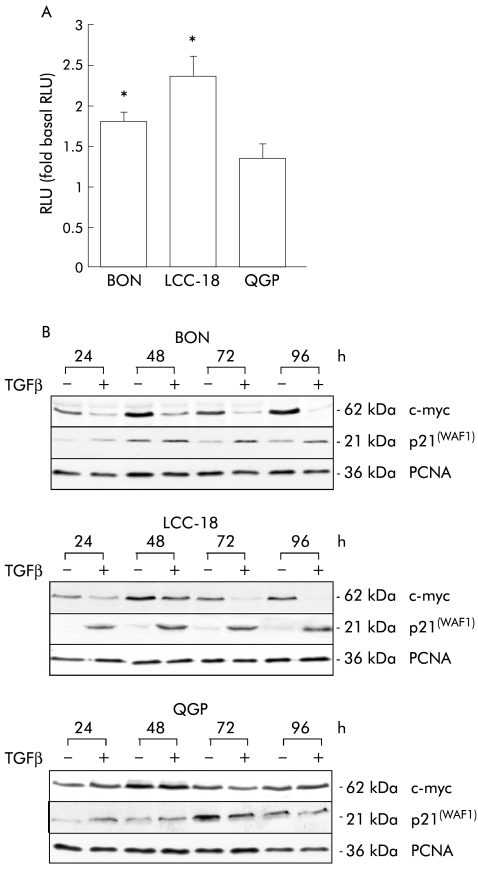

To verify the functional integrity of TGFβ-1 signalling in NET cell lines, transactivation of a TGFβ responsive luciferase reporter construct was evaluated in transient transfection assays. TGFβ-1 treatment resulted in significant transactivation of the reporter construct in BON and LCC-18 cell lines, but not in QGP cells (fig 3A ▶).

Figure 3.

Transforming growth factor β-1 (TGFβ-1) signalling in neuroendocrine tumour (NET) cell lines. (A) TGFβ-1 induces transactivation of a TGFβ-1 sensitive reporter construct in NET cell lines. Cells were transiently transfected with p3TPlux and renilla plasmids and incubated with 10 ng/ml TGFβ-1 for 24 hours. Relative luciferase activity (RLU) was determined and normalised for transfection efficiency. Data represent mean (SEM) of five independent experiments, each performed in triplicate, and determined as fold induction compared with untreated controls (*p<0.05). (B) TGFβ-1 induces endogenous TGFβ-1 downstream targets in NET cells. NET cell lines were incubated with vehicle (−) or TGFβ-1 (10 ng/ml) (+) for the indicated time points. Whole cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis using monospecific antibodies against c-myc and p21(WAF1). Monospecific proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) antibody was used to control for equal loading. A representative of three independent experiments is shown.

To further confirm TGFβ-1 mediated regulation of endogenous downstream targets for TGFβ-1, we investigated expression of c-myc and p21(WAF1). In BON and LCC-18 cells, TGFβ-1 treatment resulted in a profound time dependent downregulation of c-myc which was paralleled by induction of p21(WAF1) expression compared with untreated controls (fig 3B ▶). In accordance with the transactivation studies, TGFβ-1 treatment had no effect on c-myc or p21(WAF1) expression in QGP cells, suggesting that this cell line is resistant to TGFβ-1 treatment although signalling components were detectable (fig 3B ▶).

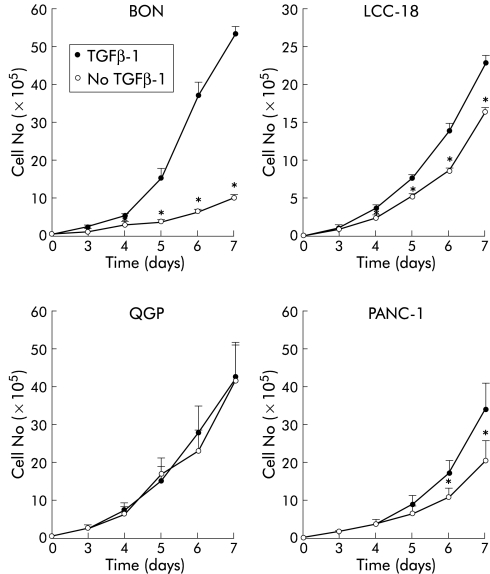

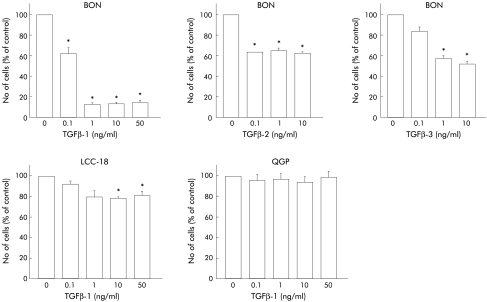

TGFβ-1 inhibits growth in NET cell lines

We next addressed the question of whether TGFβ-1 inhibits growth in human NET cells. TGFβ-1 treatment resulted in a significant time dependent inhibition of proliferation in BON and LCC-18 cells but QGP cells were not growth inhibited (fig 4 ▶). Whereas BON cells revealed a rather dramatic growth inhibition in response to TGFβ-1, LCC-18 cells were moderately growth inhibited, comparable with the growth inhibition observed in PANC-1 cells which have previously been characterised as a TGFβ-1 sensitive pancreatic cancer cell line.17 The differential TGFβ-1 sensitivity was reflected by dose-response experiments (fig 5 ▶). Half maximal concentrations required for growth inhibition were in the range of 0.1 ng/ml in BON cells whereas 10 ng/ml TGFβ-1 were required to achieve significant growth inhibition in LCC-18 cells. Again, QGP cells were TGFβ-1 resistant at concentrations of up to 50 ng/ml of the cytokine (fig 5 ▶). TGFβ-2 and TGFβ-3 also acted as growth inhibitors in BON cells but were less potent compared with the antiproliferative effects observed for TGFβ-1 (fig 5 ▶).

Figure 4.

Transforming growth factor β-1 (TGFβ-1) inhibits anchorage dependent growth of human neuroendocrine tumour (NET) cells. Subconfluent cells (104) were treated with 10 ng/ml TGFβ-1 for the indicated time periods and cell numbers were determined. Values represent mean (SEM) from at least three separate experiments, each conducted in triplicate (*p<0.05).

Figure 5.

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) mediated growth inhibition is dose dependent. Tumour cells were incubated with the indicated final concentration of TGFβ-1, TGFβ-2, and TGFβ-3 for 96 hours and cell numbers were counted. Data were obtained from at least three separate experiments, each conducted in triplicate (*p<0.05).

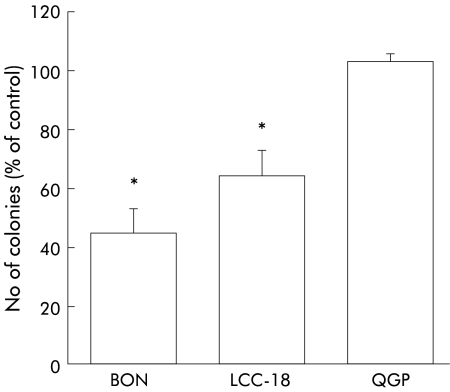

Anchorage independent growth represents a sensitive surrogate marker for tumour growth in vivo.18 We therefore evaluated the effects of TGFβ-1 on colony formation in NET cell lines (fig 6 ▶). Cells exposed to 10 ng/ml TGFβ-1 showed a significant reduction in colony number with a maximum of 44 (9)% (n=3, p<0.05) in BON cells and 64 (8)% (n=3, p<0.05) in LCC-18 cells, compared with untreated control cells. Thus substrate dependent and substrate independent growth were inhibited by TGFβ-1 in BON and LCC-18 cells but not in the QGP cell line.

Figure 6.

Transforming growth factor β-1 (TGFβ-1) inhibits anchorage independent growth of human neuroendocrine tumour cells. A single cell agar suspension containing 103 cells was incubated with 10 ng/ml TGFβ-1 for 10 days and colonies ≥30 cells were then counted and expressed as a percentage of untreated controls. Data represent mean (SEM) from at least three independent experiments, each conducted in triplicate (*p<0.05).

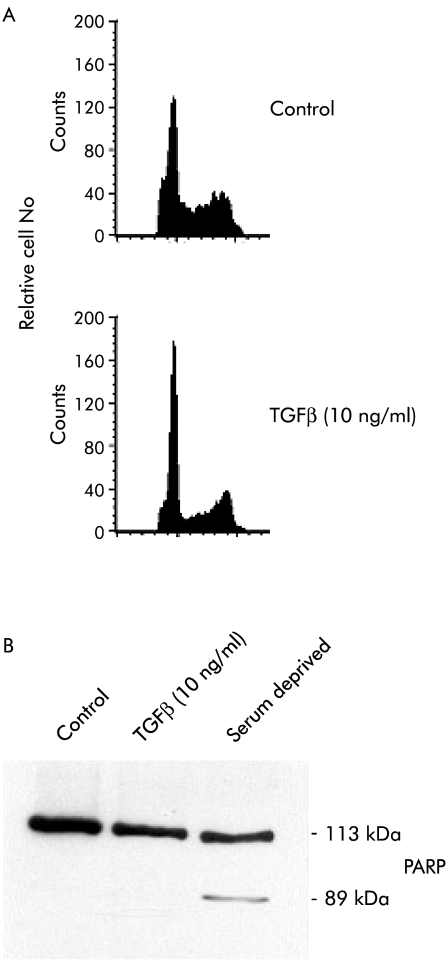

TGFβ-1 treatment results in G1 arrest

As TGFβ-1 acted as a growth inhibitory agent in two of the three NET cell lines investigated, we next attempted to discriminate induction of apoptosis from cell cycle regulation as the underlying mechanism. Using cell cycle analysis, we observed that TGFβ-1 treatment resulted in a profound G1 arrest in BON cells compared with untreated controls (fig 7 ▶). In contrast, TGFβ-1 treatment did not increase the subdiploid DNA content or induce PARP cleavage, which is used as an early marker of apoptosis, thereby indicating that induction of apoptosis does not occur in response to TGFβ-1 treatment (fig 7 ▶).

Figure 7.

Transforming growth factor β-1 (TGFβ-1) treatment results in G1 arrest. (A) Representative FACS analysis illustrating the changes in cell cycle distribution of BON cells under control condition (top panel) or treated with TGFβ-1 (10 ng/ml) for five days (bottom panel). (B) TGFβ-1 treatment did not induce apoptosis in BON cells. Cells treated with 10 ng/ml TGFβ-1 for three days were harvested and whole cell extracts were analysed for proteolytic poly(ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage. As a positive control, BON cells were serum deprived for three days before PARP analysis was performed.

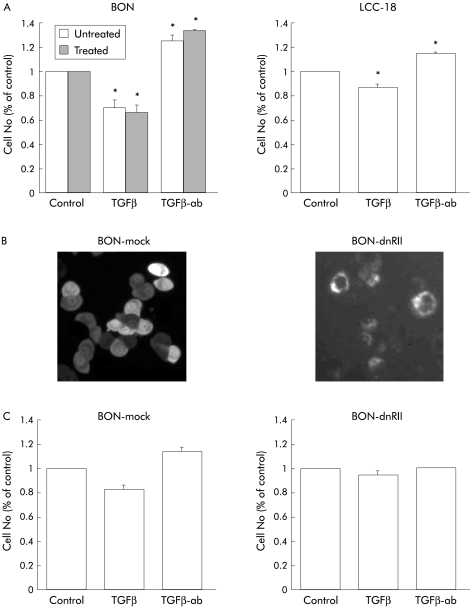

Autocrine growth inhibition by TGFβ in NET cell lines

In view of the antimitogenic effects of exogenous TGFβ-1 in BON and LCC-18 cells, we next addressed the question of whether endogenous TGFβ is also capable of restraining growth of NET cells via an autocrine mechanism.

A neutralising TGFβ antibody was used to block endogenously synthesised and secreted TGFβ. Whereas TGFβ-1 inhibited growth in BON and LCC-18 cell lines, addition of the neutralising TGFβ antibody revealed a significant induction in proliferation in both cell lines compared with isotype matched controls or untreated cells (fig 8A ▶). In an independent approach, we stably transfected a dominant negative TGFβR II into BON cells. Expression was verified by membrane localisation of the transfected GFP tagged protein (fig 8B ▶). Compared with mock transfected controls, inhibition of endogenous TGFβ signalling via expression of dn-TGFβR II completely inhibited TGFβ mediated growth inhibition (fig 8c ▶). Furthermore, the growth stimulatory effect of the neutralising TGFβ antibody was completely abolished (fig 8C ▶), suggesting autocrine growth inhibition by TGFβ1 in this NET cell line.

Figure 8.

Autocrine growth inhibition by transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) in neuroendocrine tumour (NET) cells. (A) BON and LCC-18 cells (1.5×104) were seeded and attached overnight. Cells were then incubated with 10 ng/ml TGFβ-1, a neutralising anti-TGFβ antibody (TGFβ-ab) or irrelevant control antibody (data not shown) at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml for three days. Cell number was then determined and expressed as a per cent of untreated controls. For determination of DNA synthesis, BON cells were incubated with TGFβ-1 or a neutralising anti-TGFβ antibody for 72 hours. For the last six hours, BrdU was added and DNA synthesis was then quantified by ELISA. Data represent mean (SEM) from three separate experiments, each conducted in triplicate (*p<0.05). (B) BON cells were stably transfected with a dn-TGFβR II-GFP expression construct or mock transfected with the GFP vector alone. Expression of the dn-TGFβR II-GFP fusion protein was verified by membrane localisation. (C) Transfected cell lines were analysed for growth as indicated under (A) to confirm the autoinhibitory action of endogenous TGFβ in BON cells. Shown are the mean (SEM) of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (*p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

Based on the slow growing phenotype, the current study was designed to evaluate the expression and biological significance of TGFβ-1 and its receptors in human NET disease.

Based on the work of Chaudhry and others, TGFβ isoform expression has been demonstrated in approximately 50% of mesenchymal and/or tumour cells of neuroendocrine neoplasms.5,19,20 In contrast, no information regarding expression of TGFβ receptors was available. Our immunohistochemical analysis extends these important observations in several respects: (i) both TGFβ receptors were expressed in all of the human NET specimens investigated; (ii) coexpression of TGFβ-1 and its receptors was a common phenomenon in human NET cells; and (iii) the surrounding mesenchyme also demonstrated coexpression of TGFβ-1 and its receptors in a considerable percentage. These data are in contrast with the exocrine counterparts of NET disease originating from the same organ. For example, loss of TGFβR II expression by pancreatic ductal tumour cells was reported in approximately 50% of the tumours investigated.19 Based on our expression study, the majority of human NET cells might therefore reflect a biological target for paracrine and autocrine antimitogenic actions of TGFβ-1.

However, expression of TGFβ-1 and its receptors does not necessarily imply functional integrity of the TGFβ signalling pathway because inactivation by mutations or loss of expression of TGFβ signalling components is a common phenomenon during carcinogenesis in many tumours.6,21,22 Therefore, we analysed three human NET cell lines with respect to their integrity of TGFβ signalling. All three cell lines expressed TGFβ-1, TGFβ-2, and TGFβ-3, both TGFβ receptors, as well as the TGFβ signalling components Smad 2, 3, and 4, and therefore reflected the in vivo situation. By transactivation assays as well as expression studies of the well defined TGFβ downstream targets p21(WAF1) and c-myc,8,22,23 we determined the functional integrity of TGFβ signalling in BON and LCC-18 cells whereas QGP cells did not respond to TGFβ-1. A potential cause of TGFβ-1 resistance in QGP cells is functionally inactivating mutations of TGFβ signalling components. Furthermore, we observed that QGP cells lack expression of the tumour suppressor gene pRb (data not shown) which is required for TGFβ mediated growth inhibition in most tumour cells.17,24

This observation differs from that in other tumour cell lines of the gastrointestinal tract such as the colon25 or pancreatic cancer cells26 which demonstrate genetic inactivation and/or loss of Smad and TGFβ receptor expression in 80–100%,6,27,28 thereby disabling the tumour cells to transduce TGFβ initiated antimitogenic signals.21,26

It has been well documented that TGFβ-1 switches from an inhibitor of tumour cell growth to a stimulator of growth and invasion during carcinogenesis in a variety of tumours.11 For example, while TGFβ-1 inhibits growth in non-transformed colonocytes, it stimulates proliferation in approximately 50% of colon cancer cell lines.29,30 In contrast, despite a fully transformed phenotype, BON and LCC-18 cells responded to TGFβ-1 treatment with profound growth inhibition, which was observed for anchorage dependent or anchorage independent growth. Furthermore, of the three TGFβ isoforms investigated, TGFβ-1 was the most potent in terms of growth inhibition.

In principle, TGFβ-1 is capable of eliciting its antimitogenic effects by two independent mechanisms: induction of apoptosis and G1 cell cycle arrest.8,31 Using cell cycle analysis as well as PARP cleavage experiments, we were able to demonstrate that TGFβ-1 mediated growth inhibition in NET cells is based exclusively on G1 arrest whereas no evidence for induction of apoptosis could be demonstrated. Our observation of growth inhibition via G1 cell cycle arrest in NET cells is corroborated by increased expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p21(WAF1) and decreased expression of c-myc in response to TGFβ-1 stimulation. This is in contrast with the role of TGFβ-1 in certain colon cancer cells and B-lymphoma where induction of apoptosis has been demonstrated as the central mechanism of action for growth inhibition in response to TGFβ.32–34 These data imply that the underlying mechanisms of TGFβ mediated growth inhibition are cell and tissue type dependent.

Using two independent experimental approaches we were able to demonstrate that NET cells are subject to an autocrine antimitogenic loop by endogenously produced TGFβ-1. While autocrine growth inhibition is a characteristic feature of TGFβ-1 in non-transformed cells,35 this autocrine growth inhibition is either lost or even switched to growth stimulation on malignant transformation. For example, TGFβ-1 stimulates proliferation in an autocrine manner in a colon cancer cell line36 whereas it mediates autocrine growth restraint in non-transformed colonic epithelial cells.37 These observations are therefore in contrast with the neuroendocrine colonic tumour cell line LCC-18 examined in this study where an autocrine antimitogenic loop by TGFβ-1 was preserved on malignant transformation and again highlights the tissue specific features of TGFβ in malignant NET cells.

In summary, we have provided evidence that human NET cells are subject to paracrine and autocrine growth inhibition by TGFβ1 which may contribute to the slow growing phenotype observed in the majority of human NET disease.

Acknowledgments

SR was supported by grants from DFG, Deutsche Krebshilfe, Wilhelm-Sander Stiftung, Else Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung, Sonnenfeld Stiftung, and Berliner Krebshilfe

Abbreviations

TGFβ-1, transforming growth factor β-1

TGFβR I, TGFβ type I receptor

TGFβR II, TGFβ type II receptor

NET, neuroendocrine tumour

GEP, gastroenteropancreatic

PBS, phosphate buffered saline

PARP, poly(ADP ribose) polymerase

PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen

RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

SDS, sodium dodecyl sulphate

EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein

REFERENCES

- 1.Rindi G, Villanacci V, Ubiali A. Biological and molecular aspects of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Digestion 2000;62(suppl 1):19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmitt-Gräff A, Nitschke R, Wiedenmann B. (Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine/endocrine tumors. Current pathologic-diagnostic view). Pathologe 2001;22:105–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bast RC, Kufe DW, Pollock RE, et al. Neoplasms of the Endocrine Glands. Cancer Medicine, 5th edn. Canada: BC Decker Inc, 2000.

- 4.Calender A. Molecular genetics of neuroendocrine tumors. Digestion 2000;62(suppl 1):3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhry A, Funa K, Öberg K. Expression of growth factor peptides and their receptors in neuroendocrine tumors of the digestive system. Acta Oncol 1993;32:107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyazono K. TGF-beta/SMAD signaling and its involvement in tumor progression. Biol Pharm Bull 2000;23:1125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massague J. How cells read TGF-beta signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2000;1:169–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massague J, Blain SW, Lo RS. TGFbeta signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell 2000;103:295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heldin CH, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P. TGF-beta signalling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature 1997;390:465–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akhurst RJ, Derynck R. TGF-beta signaling in cancer—a double-edged sword. Trends Cell Biol 2001;11:S44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasche B. Role of transforming growth factor beta in cancer. J Cell Physiol 2001;186:153–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Detjen KM, Welzel M, Farwig K, et al. Molecular mechanism of interferon alfa-mediated growth inhibition in human neuroendocrine tumor cells. Gastroenterology 2000;118:735–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carcamo J, Weis FM, Ventura F, et al. Type I receptors specify growth-inhibitory and transcriptional responses to transforming growth factor beta and activin. Mol Cell Biol 1994;14:3810–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Roy C, Maisnier-Patin K, Leduque P, et al. Overexpression of a dominant-negative type II TGFbeta receptor tagged with green fluorescent protein inhibits the effects of TGFbeta on cell growth and gene expression of mouse adrenal tumor cell line Y-1 and enhances cell tumorigenicity. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1999;158:87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giehl K, Seidel B, Gierschik P, et al. TGFbeta1 represses proliferation of pancreatic carcinoma cells which correlates with Smad4-independent inhibition of ERK activation. Oncogene 2000;19:4531–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartsch D, Hahn SA, Danichevski KD, et al. Mutations of the DPC4/Smad4 gene in neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors. Oncogene 1999;18:2367–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grau AM, Zhang L, Wang W, et al. Induction of p21waf1 expression and growth inhibition by transforming growth factor beta involve the tumor suppressor gene DPC4 in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res 1997;57:3929–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shin SI, Freedman VH, Risser R, et al. Tumorigenicity of virus-transformed cells in nude mice is correlated specifically with anchorage independent growth in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1975;72:4435–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venkatasubbarao K, Ahmed MM, Mohiuddin M, et al. Differential expression of transforming growth factor beta receptors in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res 2000;20:43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaudhry A, Öberg K, Gobl A, et al. Expression of transforming growth factors beta 1, beta 2, beta 3 in neuroendocrine tumors of the digestive system. Anticancer Res 1994;14:2085–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Derynck R, Akhurst RJ, Balmain A. TGF-beta signaling in tumor suppression and cancer progression. Nat Genet 2001;29:117–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakefield LM, Roberts AB. TGF-beta signaling: positive and negative effects on tumorigenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2002;12:22–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staller P, Peukert K, Kiermaier A, et al. Repression of p15INK4b expression by Myc through association with Miz-1. Nat Cell Biol 2001;3:392–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voss M, Wolff B, Savitskaia N, et al. TGFbeta-induced growth inhibition involves cell cycle inhibitor p21 and pRb independent from p15 expression. Int J Oncol 1999;14:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hahn SA, Schutte M, Hoque AT, et al. DPC4, a candidate tumor suppressor gene at human chromosome 18q21.1. Science 1996;271:350–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simeone DM, Pham T, Logsdon CD. Disruption of TGFbeta signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancer cells. Ann Surg 2000;232:73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartsch D, Barth P, Bastian D, et al. Higher frequency of DPC4/Smad4 alterations in pancreatic cancer cell lines than in primary pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Cancer Lett 1999;139:43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villanueva A, Garcia C, Paules AB, et al. Disruption of the antiproliferative TGF-beta signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene 1998;17:1969–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schroy P, Rifkin J, Coffey RJ, et al. Role of transforming growth factor beta 1 in induction of colon carcinoma differentiation by hexamethylene bisacetamide. Cancer Res 1990;50:261–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu S, Huang F, Hafez M, et al. Colon carcinoma cells switch their response to transforming growth factor beta 1 with tumor progression. Cell Growth Differ 1994;5:267–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perlman R, Schiemann WP, Brooks MW, et al. TGF-beta-induced apoptosis is mediated by the adapter protein Daxx that facilitates JNK activation. Nat Cell Biol 2001;3:708–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gold LI. The role for transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) in human cancer. Crit Rev Oncog 1999;10:303–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen RH, Chang TY. Involvement of caspase family proteases in transforming growth factor-beta-induced apoptosis. Cell Growth Differ 1997;8:821–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saltzman A, Munro R, Searfoss G, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta-mediated apoptosis in the Ramos B-lymphoma cell line is accompanied by caspase activation and Bcl-XL downregulation. Exp Cell Res 1998;242:244–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grande JP, Warner GM, Walker HJ, et al. TGF-beta1 is an autocrine mediator of renal tubular epithelial cell growth and collagen IV production. Exp Biol Med (Maywood ) 2002;227:171–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang F, Newman E, Theodorescu D, et al. Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF beta 1) is an autocrine positive regulator of colon carcinoma U9 cells in vivo as shown by transfection of a TGF beta 1 antisense expression plasmid. Cell Growth Differ 1995;6:1635–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deng X, Bellis S, Yan Z, et al. Differential responsiveness to autocrine and exogenous transforming growth factor (TGF) beta1 in cells with nonfunctional TGF-beta receptor type III. Cell Growth Differ 1999;10:11–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]