Abstract

Aims: Impaired gastric accommodation is a major pathophysiological mechanism in functional dyspepsia. The aim of the present work was to assess a satiety drinking test in the evaluation of accommodation in health and dyspepsia.

Methods: Twenty five controls and 37 severely dyspeptic patients seen at a tertiary care centre completed a dyspepsia questionnaire, and gastric emptying and gastric barostat studies. The amount of liquid meal ingested at maximum satiety during a slow satiety drinking test was determined. In controls, we studied the influence of caloric density and of pharmacological agents that influence accommodation.

Results: In patients, satiety scores were higher and maximum satiety occurred at lower calories (542 (50) v 1508 (53) kcal; p<0.0001). Six patients had required nutritional support, but excluding these did not alter the correlations. With increasing severity of early satiety, less calories were ingested at maximum satiety. In multivariate analysis, the amount of calories was significantly correlated to accommodation but not to gastric emptying or sensitivity. Sensitivity and specificity of the satiety test in predicting impaired accommodation reached 92% and 86%, respectively. At different caloric densities, ingested volume rather than caloric load determined maximum satiety. Pharmacological agents (sumatriptan, cisapride, erythromycin) affected the satiety test according to their effect on accommodation.

Conclusion: A slow caloric drinking test can be used to evaluate accommodation and early satiety. It provides a non-invasive method of predicting impaired accommodation and quantifying pharmacological influences on accommodation.

Keywords: gastric accommodation, satiety, functional dyspepsia

Functional dyspepsia is a clinical syndrome characterised by chronic or recurrent epigastric pain or discomfort without an identifiable cause by conventional diagnostic means.1 The pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia seems to be heterogeneous, and suggested mechanisms include delayed gastric emptying, visceral hypersensitivity to distension, impaired gastric accommodation to a meal, abnormal duodenojejunal motility, Helicobacter pylori gastritis, or central nervous system dysfunction.2–7

The accommodation reflex consists of relaxation of the proximal stomach, providing the meal with a reservoir and enabling a volume increase without a rise in pressure. Several recent studies suggest that impaired accommodation to a meal is an important pathophysiological mechanism in dyspepsia.5,8–11 We demonstrated that 40% of dyspeptic patients have impaired accommodation, and this is associated with early satiety and weight loss.5 Acute studies established the therapeutic potential of fundus relaxing therapy in dyspeptic patients with impaired accommodation.5

However, identifying patients with impaired accommodation and studying drugs to correct this disorder have been hampered by a lack of easily applicable tools. Gastric barostat studies require that the patient swallows a large balloon and have specific pitfalls.12 Ultrasound studies of the proximal stomach are labour intensive and require specialised equipment.13 More recently, three dimensional single photon emission computed tomography of the gastric wall was developed to quantify accommodation but this requires expensive equipment and specific software, and is associated with radiation exposure.14

We previously described a simple non-invasive drinking test to quantify meal induced satiety.5 The test is highly reproducible15 and was found to correlate well with barostat measurement of accommodation in a small group of patients.5 If adequately validated, the test might provide an attractive method for detecting impaired accommodation in disease states and for quantifying pharmacological influences on accommodation.

The aims of the present study therefore were: (1) to compare the satiety test in health and in dyspeptic patients, (2) to study the relationship of the satiety test with gastric physiology and pathophysiology, (3) to study the influence of changes in caloric density, and (4) to study the influence of pharmacological agents that modify gastric accommodation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects

A total of 27 healthy controls (16 men; aged 26.5 (1.0) years) and 37 functional dyspepsia patients (four men; aged 36.1 (1.7) years) participated in this study. None of the healthy subjects reported symptoms or a history of gastrointestinal disease or drug allergies, nor were they taking any medication. Some volunteers participated in more than one aspect of the studies.

Patients presented to the motility clinic of a tertiary care centre because of severe epigastric symptoms, and all underwent careful history taking and clinical examination, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, routine biochemistry, and upper abdominal ultrasound. Inclusion criteria were the presence of dyspeptic symptoms for at least three months, in the absence of organic, systemic, or metabolic disease. Dyspeptic symptoms had to be present at least three days per week, with two or more symptoms scored as relevant or severe on the questionnaire (see below). Exclusion criteria were the presence of oesophagitis, gastric atrophy, or erosive gastroduodenal lesions on endoscopy, heartburn as a predominant symptom, a history of peptic ulcer, major abdominal surgery, underlying psychiatric illness, and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, or drugs affecting gastric acid secretion. During upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, biopsies were taken from the antrum and corpus to stain with cresyl violet for the presence of H pylori. In patients with relevant or severe epigastric burning on the symptom questionnaire, 24 hour oesophageal pH monitoring was performed, and found to be normal (<4% of time pH <4). A psychiatrist ruled out anorexia nervosa in patients with weight loss. Six patients had been hospitalised at another hospital for nutritional support (parenteral nutrition) during the months preceding referral to the motility clinic; two patients later required enteral nutrition. However, all measurements were done as outpatient procedures with patients on oral feeding. All drugs potentially affecting gastrointestinal motility were discontinued at least one week prior to the barostat and gastric emptying studies. Informed consent was obtained from each participant. The ethics committee of the university hospital had previously approved the protocol.

Symptom questionnaire

Each subject completed a reproducible dyspepsia questionnaire, as reported previously.4,5,15 The subject was asked to grade the intensity (0–3: 0=absent; 1=mild, present but not very bothersome; 2=relevant, bothersome but not interfering with daily activities; and 3=severe, interfering with daily activities) of eight different symptoms (epigastric pain, bloating, postprandial fullness, early satiety, nausea, vomiting, belching, and epigastric burning). Also, weight lost since the onset of symptoms, if present, was noted. As the questionnaire addresses several different symptoms, which include physiological sensations such as fullness after a meal or belching, up to two mild symptoms were accepted in healthy controls.

Satiety drinking test

Subjects were studied in the morning after an overnight fast. A peristaltic pump (Minipuls2; Gilson, Villiers-Le-Bel, France) filled one of two beakers at a rate of 15 ml/min with a liquid meal (Nutridrink; Nutricia, Bornem, Belgium). Subjects were requested to maintain intake at the filling rate, thereby alternating the beakers as they were filled and emptied. At five minute intervals, they scored their satiety using a graphic rating scale that combined verbal descriptors on a scale graded 0–5 (1=threshold, 5=maximum satiety). Participants were instructed to cease meal intake when a score of 5 was reached.

Gastric emptying studies

Solid gastric emptying was measured using the validated 13C octanoic acid breath test.16 Briefly, all studies were carried out in the morning after an overnight fast. The test meal consisted of 60 g of white bread, one egg, the yolk of which was doped with 13C octanoic acid sodium salt, and 300 ml of water. Breath samples were taken before the meal and at 15 minute intervals for 240 minutes postprandially.

Sensitivity to gastric distention and gastric accommodation

Sensitivity to gastric distention and gastric accommodation to a meal were studied using a gastric barostat, as previously described.4,5 Following an overnight fast of at least 12 hours, a double lumen polyvinyl tube (Salem sump tube 14Ch; Sherwood Medical, Petit-Rechain, Belgium) with an adherent plastic bag (1200 ml capacity;17 cm maximal diameter) finely folded, was introduced through the mouth and secured to the subject’s chin with adhesive tape. The position of the bag was checked fluoroscopically. The polyvinyl tube was then connected to a programmable barostat device (Synectics Visceral Stimulator, Stockholm, Sweden). To unfold the bag, it was inflated with a fixed volume of 300 ml of air for two minutes with the study subject in a recumbent position, and again deflated. Subjects were then positioned in a comfortable sitting position with knees bent (80°) and trunk upright in a specifically designed bed.

After a 30 minute adaptation period, minimal distending pressure (MDP) was first determined by increasing intrabag pressure by 1 mm Hg every three minutes until a volume of 30 ml or more was reached.17 This pressure level equilibrates the intra-abdominal pressure. Subsequently, isobaric distensions were performed in stepwise increments of 2 mm Hg starting from MDP, each lasting two minutes, while the corresponding intragastric volume was recorded. Subjects were instructed to score their perception of upper abdominal sensations at the end of every distending step, using a graphic rating scale that combined verbal descriptors on a scale graded 0–6.17 The end point of each sequence of distensions was established at an intrabag volume of 1000 ml or when the subject reported discomfort or pain (score 5 or 6).

After a 30 minute adaptation period with the bag completely deflated, the pressure level was set at MDP + 2 mm Hg for at least 90 minutes. After 30 minutes, a liquid meal (200 ml, 300 kcal, 13% proteins, 48% carbohydrates, 39% lipids; Nutridrink, Nutricia) was administered. Gastric tone measurement was continued for 60 minutes after the meal.

Study design

In all patients and in 25 healthy subjects, the relationship of the satiety drinking test to gastric physiology and pathophysiology was studied. On three separate days, a maximum of one week apart, they underwent a satiety drinking test, a gastric barostat study, and a gastric emptying study in a randomised order.

In 14 controls, we studied the influence of caloric density on the satiety drinking test. They underwent three different satiety tests on separate occasions, three days to one week apart. In a randomised order, a mixed liquid meal (8% proteins, 47% carbohydrates, 45% lipids; Nutri-40, Nutricia) was used at a caloric density of 1.5, 1.75, or 2 kcal/ml.

In controls, we also studied the influence on the satiety test of pharmacological agents that modify gastric accommodation. Eleven controls underwent the satiety test twice, at least three days apart, after pretreatment with placebo or sumatriptan 6 mg subcutaneously, immediately prior to the meal in a double blind, randomised, crossover fashion. Twelve controls underwent the satiety drinking twice, at least two weeks apart, after five days pretreatment with placebo or cisapride 3×10 mg/day in a double blind, randomised, crossover fashion. The drug was administered 15 minutes prior to the start of the satiety test. In eight healthy subjects the satiety drinking test was done twice, at least three days apart, after pretreatment with placebo or erythromycin 200 mg intravenously/20 minutes at the start of the meal in a double blind, randomised, crossover fashion.

Data analysis

The end point of the satiety test was the amount of calories ingested until the occurrence of maximum satiety (score 5).

Gastric half emptying time (t1/2) was calculated from the 13CO2 content of breath samples, as previously described.16 In the gastric sensitivity studies, for each two minute distending period, the intragastric volume was calculated by averaging the recording. Discomfort threshold was defined as the first level of pressure and the corresponding volume that provoked a score of 5 or more. Pressure thresholds were expressed relative to MDP.4 Gastric tone before and after administration of the meal was measured by calculation of the mean balloon volume for consecutive five minute intervals. Meal induced gastric relaxation was quantified as the difference between the average volumes over 30 minutes before and 60 minutes after administration of the meal.5

Statistical analysis

The normal range (mean (2 SD)) for the satiety test was calculated from the healthy volunteer data. In patients and controls, the relationships between the amount of calories at maximum satiety on the one hand and gastric emptying rate or sensitivity to gastric distention or meal induced relaxation on the other hand, were evaluated by linear regression analysis. The relationship of the satiety drinking test to symptoms was analysed by comparing the amount of calories at maximum satiety at three possible intensity cutoffs (≥1 v 0; ≥2 v ≤1; and 3 v ≤2) for each individual symptom.

Stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis was used to identify the association between the end point of the satiety drinking test and demographic variables, pathophysiological abnormalities, or symptom parameters. p values of 0.05 and 0.1 were chosen as cut off points to enter and exit the stepwise procedure. Odds ratios with 95% confidence interval were computed.

The results for the end point of the satiety drinking test in healthy volunteers and in patients were compared by Student’s t test. The sensitivity and specificity of the satiety drinking test in predicting impaired accommodation was calculated. The amount of calories at maximum satiety using different caloric densities or after pretreatment with drug or with placebo was compared using the Student’s t test. The relationship between ingested meal and satiety scores after drug treatment was compared by ANOVA.

Differences were considered significant at the 5% level. All data are given as mean (SEM). Statistical evaluations were performed using specialised software (SAS, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

RESULTS

Characteristics of healthy volunteers and functional dyspepsia patients

Table 1 ▶ summarises symptoms in the patient groups. Postprandial fullness and nausea were present in 100% and 95% of patients, respectively. Belching (91%), bloating (86%), early satiety (76%), and epigastric pain (54%) were also frequently reported. Vomiting and epigastric burning sensation were present in 38% and 46%, respectively. Weight loss in excess of 5% was present in 22 patients (59%). None of the healthy volunteers reported relevant or severe symptoms. Thirteen volunteers did not report any dyspeptic symptoms; six reported one and six reported two mild symptoms.

Table 1.

Frequency of severity grading for each of eight dyspepsia symptoms in 37 patients with functional dyspepsia

| 0 (absent) | 1 (mild) | 2 (relevant) | 3 (severe) | |

| Postprandial fullness | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 11 (30) | 22 (59) |

| Bloating | 5 (14) | 0 (0) | 10 (27) | 22 (59) |

| Epigastric pain | 17 (66) | 6 (16) | 1 (3) | 13 (35) |

| Early satiety | 9 (24) | 8 (22) | 12 (32) | 8 (22) |

| Nausea | 2 (5) | 6 (16) | 14 (38) | 15 (41) |

| Vomiting | 23 (62) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 12 (32) |

| Belching | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 21 (57) | 11 (30) |

| Epigastric burning | 20 (54) | 8 (22) | 6 (16) | 3 (8) |

Numbers in parentheses represent row percentages.

In healthy subjects, gastric emptying, sensitivity to distention, and accommodation were all within the previously established normal range.4,5,19 All patients were H pylori negative; no data on H pylori status were available for the controls. Twelve patients (32%) had delayed emptying,19 23 patients (62%) had hypersensitivity to gastric distention,4 and 13 (35%) had impaired accommodation.5

Satiety drinking test in health and dyspepsia

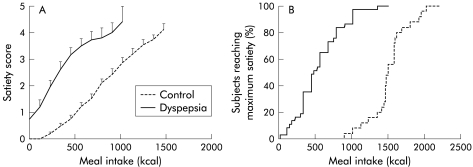

With increasing amounts of calories ingested, increasing satiety scores were reported (fig 1 ▶). A highly significant correlation was obtained between satiety scores and the amount of kcal ingested (r=0.87, p<0.001). In healthy volunteers, maximum satiety occurred after ingestion of 1508 (53) kcal (1005 (35) ml). The lower limit of normal was 979 kcal (653 ml). The end point of the satiety drinking test in healthy controls was not influenced by age, sex, or body mass index (data not shown).

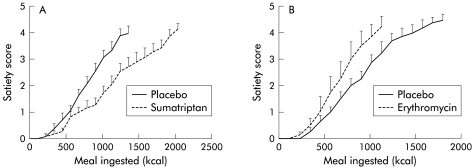

Figure 1.

(A) Satiety scores during the satiety drinking test in healthy controls (n=25) and in patients with functional dyspepsia (n=37). With increasing amounts of calories ingested, increasing satiety scores were generated. In patients, satiety scores were significantly higher compared with healthy subjects (ANOVA, p<0.001). Data are shown until the first data point reached by less than half of the subjects. (B) Cumulative percentage of subjects reaching maximum satiety (satiety score 5) during the satiety drinking test in healthy controls and patients with functional dyspepsia.

In patients, satiety scores for the same amount of kcal ingested were significantly higher (p<0.001) and maximum satiety occurred at significantly lower calories compared with healthy subjects (542 (50) v 1508 (53) kcal or 361 (33) v 1005 (35) ml; p<0.0001) (fig 1 ▶).

Univariate analysis

In 32 patients (86%), the end point of the satiety test was below the normal range in healthy volunteers. Patients with a satiety test within the normal range were older (50 (5) v 34 (2) years; p<0.001) but did not differ significantly in terms of sex or body mass index. Patients with a normal drinking test had a lower prevalence of early satiety (0/5 v 28/32; p<0.001) and a higher prevalence of relevant or severe epigastric burning (3/5 v 6/32; p<0.05).

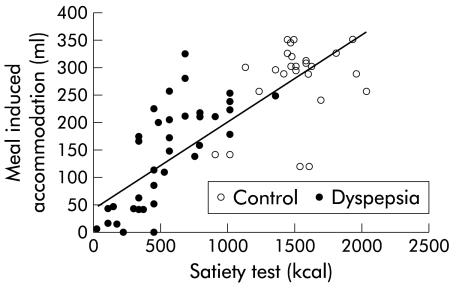

When all subjects were considered, a significant correlation was found between the end point of the drinking test and meal induced accommodation, as measured with the barostat (r=0.76, p<0.001) (fig 2 ▶). The satiety test was weakly correlated with age (r=0.31, p=0.015) but not with body mass index. There was a weak but significant correlation with sensitivity to gastric distention (r=0.50, p<0.001) and with gastric half emptying time (r=−0.40, p=0.001). When only patients with functional dyspepsia were considered, the end point of the satiety drinking test was only significantly correlated with meal induced accommodation (r=0.71, p<0.001) (fig 2 ▶) and with age (r=0.48, p<0.005). When patients who previously required nutritional support were excluded, similar correlations for the whole group and for patients only were obtained (respectively r=0.75 and r=0.73; p<0.005).

Figure 2.

Relationship between the end point of the satiety drinking test and the size of meal induced accommodation, determined by gastric barostat in healthy controls (n=25) and in patients with functional dyspepsia (n=37). A significant correlation between both measurements was found (r=0.76, p<0.001). In patients, maximum satiety occurred at significantly lower caloric intake compared with healthy subjects (542 (50) v 1508 (53) kcal; p<0.0001).

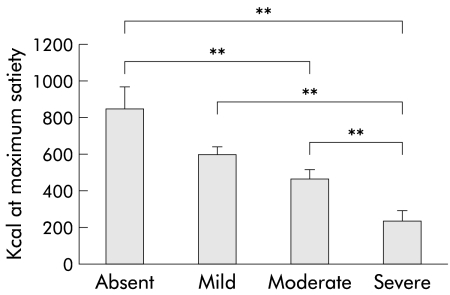

In patients, the amount of calories ingested at maximum satiety decreased progressively with increasing severity of early satiety (satiety scores 0–3, respectively: 850 (122), 604 (41), 472 (49), and 241 (56) kcal or 567 (82), 403 (27.3), 315 (33), and 161 (37) ml; all p<0.05 except for comparison between scores 0 and 1, and 1 and 2) (fig 3 ▶).

Figure 3.

Relationship between severity of early satiety and the end point of the satiety drinking test in 37 patients with functional dyspepsia. The amount of calories ingested at maximum satiety decreased progressively with increasing severity of early satiety (**p<0.005).

Multivariate analysis

Logistic regression analysis of demographic, symptomatic, and physiopathological correlates in all subjects showed that a low caloric intake in the satiety test was significantly associated with the presence of abnormal accommodation (odds ratio 5.132 (95% confidence interval 1.292–22.497); p<0.01), with the presence of early satiety (7.845 (2.345–27.782); p<0.001), with the absence of vomiting (0.113 (0.028–0.426); p<0.001), and with the absence of relevant or severe vomiting (0.166 (0.046–0.568); p<0.005). At each cut off, no symptom was consistently associated with the result of the caloric drinking test. Other factors with a significant association in the univariate analysis, such as age, gastric emptying, sensitivity to gastric distention, or severity of epigastric burning were not independent risk factors in the multivariate analysis.

When the multivariate analysis was limited to patients only, similar associations were found. A low caloric intake in the test was significantly associated with abnormal accommodation (odds ratio 6.747 (95% confidence interval 1.785–28.401); p=0.005). At each cut off, no symptom was consistently associated with the result of the test. At a symptom severity cut off of ≥1 versus 0, a low end point of the test was associated with the presence of early satiety (13.846 (2.640–87.547); p<0.005) and with the absence of vomiting (0.121 (0.029–0.459); p<0.005). At a cut off of ≥2 versus ≤1, there was an association with absence of relevant or severe vomiting (0.237 (0.064–0.819); p<0.05).

Sensitivity and specificity of the satiety drinking test

The sensitivity and specificity of the satiety test in distinguishing dyspepsia from health were 86% and 97%, respectively. Within the dyspeptic patient population, we examined the sensitivity and specificity of the satiety test in predicting impaired accommodation (table 2 ▶). At a cut off of 400 kcal (267 ml), the sensitivity and specificity of the satiety test in predicting impaired accommodation were 92% and 86%, respectively. When patients who previously required nutritional support were omitted, a slightly lower specificity was obtained (table 2 ▶).

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity in predicting impaired gastric accommodation using the satiety drinking test at different cut off levels

| Cut off (kcal) | |||||||||

| 300 | 350 | 400 | 450 | 500 | 550 | 600 | 650 | 700 | |

| Sensitivity (%) | 46 | 92 | 92 | 92 | 92 | 92 | 92 | 92 | 100 |

| Specificity (%) | 100 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 67 | 63 | 52 | 52 | 48 |

| Sensitivity* (%) | 71 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Specificity* (%) | 100 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 54 | 50 | 39 | 39 | 33 |

*Values obtained when patients who required nutritional support were excluded from the analysis.

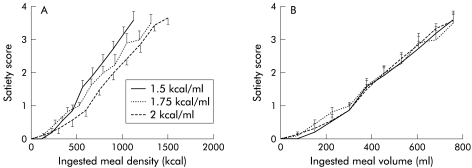

Influence of caloric density

Fourteen healthy volunteers (eight men, 20–39 years) were studied on three separate occasions, ingesting either a 1.5, 1.75, or 2 kcal/ml meal. With increasing caloric density, maximum satiety occurred at progressively higher caloric intakes (1478 (72) kcal, 1655 (98) kcal (p<0.01), and 1785 (84) kcal, respectively (p<0.001)) (fig 4A ▶). However, the satiety scores according to ingested volume and volumes at maximum satiety did not differ significantly (958 (48) ml, 986 (56) ml (NS), and 891 (41) ml (NS), respectively) (fig 4B ▶).

Figure 4.

(A) Influence of caloric density on satiety scores per amount of kcal ingested during the satiety drinking test in 11 healthy subjects. Increasing caloric density was associated with a lower satiety score for the same amount of calories ingested. Data are shown until the highest amount of ingested calories reached by all subjects. (B) Influence of caloric density on satiety scores per volume of meal ingested during the satiety drinking test, using the data from (A) expressed as volume. Increasing caloric density did not alter the satiety score for the same volume of meal ingested.

Influence of pharmacological agents that modify gastric accommodation to a meal

Eleven healthy volunteers (seven males, 20–29 years) were studied on two separate occasions, after pretreatment with placebo or sumatriptan 6 mg subcutaneously. Sumatriptan significantly decreased the average satiety scores for the same amount of kcal ingested (p<0.003, ANOVA) (fig 5A ▶). Pretreatment with sumatriptan significantly enhanced the amount of food ingested from 1493 (94) kcal (995 (63) ml) to 1831 (97) kcal (1221 (65) ml) (p=0.01) (fig 6 ▶).

Figure 5.

(A) Influence of sumatriptan on meal induced satiety in 11 healthy controls. Satiety scores for the same amount of calories ingested were significantly lower after pretreatment with sumatriptan. Data are shown until the highest amount of ingested calories reached by all subjects. (B) Influence of erythromycin on meal induced satiety in eight healthy controls. Satiety scores for the same amount of calories were significantly higher after pretreatment with erythromycin. Data are shown until the highest amount of ingested calories reached by all subjects.

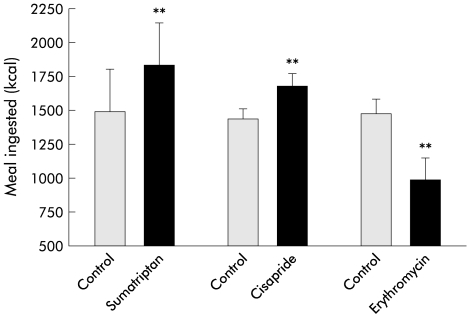

Figure 6.

Influence of pretreatment with sumatriptan (n=11), cisapride (n=12), and erythromycin (n=8) on meal induced satiety in healthy controls. Sumatriptan and cisapride significantly enhanced the amount of meal ingested at maximum satiety whereas erythromycin significantly decreased the amount of meal ingested at maximum satiety (**p<0.005).

Twelve healthy volunteers (six males, 20–39 years) were studied twice, after pretreatment with placebo or cisapride 10 mg three times daily for five days. Cisapride significantly enhanced the amount of food ingested from 1444 (78) kcal (963 (52) ml) to 1684 (93) kcal (1123 (62) ml) (p<0.05) (fig 6 ▶). Cisapride significantly decreased the average satiety scores for the same amount of kcal ingested (p<0.05, ANOVA).

Eight healthy volunteers (five males, 20–29 years) were studied on two separate occasions, after pretreatment with placebo or erythromycin 200 mg intravenously. Erythromycin significantly decreased the amount of food ingested (1483 (110) v 994 (165) kcal; p<0.05) and significantly increased the average satiety scores for the same amount of kcal ingested (p<0.003, ANOVA) (fig 5B ▶, fig 6 ▶).

DISCUSSION

Functional dyspepsia is one of the most frequently encountered disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, accounting for up to 5% of general practitioner consultations.19 Recent studies have established that functional dyspepsia is a heterogeneous disorder in which different underlying pathophysiological disturbances are associated with specific symptom patterns.3–5,18 Therefore, correction of the underlying pathophysiological abnormality seems an attractive approach in obtaining symptom relief in functional dyspepsia.20

Impaired accommodation to a meal is a frequently encountered pathophysiological abnormality in functional dyspepsia, and acute studies established the therapeutic potential of fundus relaxing therapy in dyspeptic patients with impaired accommodation to a meal.5,8–11,13 However, symptom pattern lacks the sensitivity and specificity to adequately identify patients with impaired accommodation21 and the currently available tests to quantify accommodation to a meal are invasive, labour intensive, or associated with radiation exposure.12–14

In the present study, we further investigated the use of a slow caloric drinking test in the assessment of gastric accommodation in health and in patients with functional dyspepsia. Previously, we established that this satiety drinking test has excellent reproducibility and is independent of sex in healthy controls.15 As a group, patients with functional dyspepsia ingested a significantly lower amount of calories at maximum satiety, and the end point of the satiety drinking test distinguished most patients from controls. Patients were asked to score meal induced satiety and this determined the end point of the test. However, in dyspepsia, several symptoms are generally present at the same time, and an additional influence of other symptoms or psychological factors such as vigilance cannot be excluded. In the multivariate analysis, both the presence of early satiety and the absence of relevant or severe vomiting were associated with a low caloric intake in the satiety test. Further studies are needed to assess the influence of other symptoms.

In univariate analysis, several demographic and pathophysiological characteristics were related to the end point of the satiety test. This is due to the fact that dyspeptic patients as a group drank less and had abnormal function tests. Gastric accommodation to a meal showed the best correlation with the result of the slow caloric drinking test. In multivariate analysis, only accommodation to a meal was an independent factor consistently associated with the outcome of the satiety drinking test. Gastric emptying rate and sensitivity to gastric distention did not seem to affect the results of the satiety drinking test in patients. We used the gastric emptying breath test, which does not provide sensitive information on early emptying phases. A contribution of early gastric emptying and duodenal nutrient exposure to the higher satiety scores in patients cannot be excluded. In patients with severe functional dyspepsia, seen at a tertiary referral centre, the end point of the satiety drinking test reflects the severity of early satiety and predicts the presence of impaired accommodation with good sensitivity and specificity. Previously, we established the relationship between impaired accommodation and early satiety.5 The test therefore offers the potential to screen for impaired accommodation in a non-invasive way. The present study evaluated the usefulness of the satiety drinking test in a tertiary care centre population of dyspeptic patients with severe symptoms, related to meal ingestion. Moreover, patient selection was based on meal related symptoms with a minimum severity and according to the Rome I duration criteria of three months. By coincidence, none of the patients was infected with H pylori. Additional validation studies are required in unselected dyspeptic patients with a lesser symptom severity before large scale use as a screening test can be considered useful.

Several groups have investigated the use of drinking tests in functional dyspepsia but a clear correlation with symptom pattern or with pathophysiology has not been reported.22–24 However, these were mainly rapid drinking tests, often low or non-caloric, aimed at mimicking gastric balloon distention in the assessment of sensitivity to gastric distention. Recently, Boeckxstaens et al reported the lack of correlation of a rapid caloric or water drinking test with gastric accommodation or with sensitivity to gastric distention.24 In the present study, we used a slow drinking, high caloric drinking test, and it seems likely that both properties are essential in obtaining a relationship with meal induced accommodation.

Several factors have been implicated in the control of satiety in humans, including activation of gastric mechanoreceptors and the presence of nutrients in the duodenum with activation of neurohormonal pathways.25–27 The accommodation reflex is a relatively slow onset reflex, reaching a maximum, on average, 15 minutes after meal ingestion.5 Therefore, a major influence of the gastric accommodation reflex on a rapid drinking test seems unlikely. The rapid drinking test has a short time course of, on average, seven minutes in patients, making it inappropriately timed for estimation of meal induced gastric accommodation.24,28 The currently available techniques to quantify gastric accommodation all aim at assessing proximal gastric volume, and impaired accommodation is essentially a problem of insufficient volume capacity of the proximal stomach. Exposure of the duodenum to nutrients, especially lipids, will cause enhanced contractile activity of the pylorus, thereby effectively inhibiting additional emptying of nutrients from the stomach.29 In a preliminary study using a radiolabelled drinking test in controls, emptying of liquid occurred only in the earliest phase of the test, and satiety correlated best with proximal stomach filling.30 These findings suggest that proximal gastric storage capacity is the main determinant of the end point of the satiety drinking test. In the present study, in keeping with this hypothesis, we observed that increased caloric density (from 1.5 to 1.75 and 2 kcal/ml) of the test meal led to ingestion of higher amounts of calories but similar volumes. In low caloric or water load tests, due to the absence of feedback inhibition, gastric emptying may have a major influence on the actual filling of the proximal stomach.

To further establish the relationship between accommodation and the satiety drinking test, we studied the influence of drugs that alter gastric accommodation. Both sumatriptan and cisapride were shown to enhance accommodation to a meal, and erythromycin was shown to inhibit accommodation to a meal.5,31–33 Sumatriptan slows gastric emptying whereas cisapride and erythromycin are both gastroprokinetic drugs.34–36 As the end point of the satiety test was enhanced by sumatriptan and cisapride and decreased by erythromycin, the influence of these agents matches their influence on gastric accommodation, and not their influence on gastric emptying rate. The satiety drinking test therefore offers the potential to screen for drugs that might improve impaired accommodation in a non-invasive way.

In summary, a slow caloric drinking test can distinguish most severe dyspeptic patients from controls. The end point of the test was significantly correlated to gastric accommodation, but not to gastric emptying or to sensitivity to distention. In functional dyspepsia patients, the end point of the satiety drinking test reflects the severity of early satiety and predicts the presence of impaired accommodation with good sensitivity and specificity. At different caloric densities, the volume of meal ingested is a major determinant of the end point. Pharmacological agents affect the result of the satiety test according to their effect on gastric accommodation to a meal. We conclude that the slow caloric drinking test provides an attractive non-invasive method to detect impaired accommodation in functional dyspepsia and for quantifying pharmacological influences.

Abbreviations

MDP, minimal distending pressure

REFERENCES

- 1.Talley NJ, Stanghellini V, Heading RC, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gut 1999;45 (suppl II):37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Paternico A, et al. Risk indicators of delayed gastric emptying of solids in patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 1996;110:1036–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mearin F, Cucala M, Azpiroz F, et al. The origin of symptoms on the brain-gut axis in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 1991;101:999–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tack J, Caenepeel P, Fischler B, et al. Hypersensitivity to gastric distention is associated with symptoms in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2001;121:526–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tack J, Piessevaux H, Coulie B, et al. Role of impaired gastric accommodation to a meal in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 1998;115:1346–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilmer A, Van Cutsem E, Andrioli A, et al. Prolonged ambulatory gastrojejunal manometry in severe motility-like dyspepsia: lack of correlation between dysmotility, symptoms and gastric emptying. Gut 1998;42:36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danesh J, Lawrence M, Murphy M, et al. Systematic review of the epidemiological evidence on Helicobacter pylori infection and nonulcer or uninvestigated dyspepsia. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1192–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Troncon LEA, Bennett RJM, Ahluwalia NK, et al. Abnormal distribution of food during gastric emptying in functional dyspepsia patients. Gut 1994;35:327–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hausken T, Berstad A. Wide gastric antrum in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Effect of cisapride. Scand J Gastroenterol 1992;27:427–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ricci R, Bontempo I, La Bella A, et al. Dyspeptic symptoms and gastric antrum distribution. An ultrasonographic study. Ital J Gastroenterol 1987;19:215–17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salet GAM, Samsom M, Roelofs JMM, et al. Responses to gastric distention in functional dyspepsia. Gut 1998;42:823–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitehead WE, Delvaux M. Standardization of procedures for testing smooth muscle tone and sensory thresholds in the gastrointestinal tract. Dig Dis Sci 1997;42:223–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilja OH, Hausken T, Wilhelmsen I, et al. Impaired accommodation of proximal stomach to a meal in functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci 1996;41:689–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuiken SD, Samsom M, Camilleri M, et al. Development of a test to measure gastric accommodation in humans. Am J Physiol 1999;277:G1217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuomo R, Sarnelli G, Grasso R, et al. Functional dyspepsia symptoms, gastric emptying and satiety provocative test: analysis of relationships. Scand J Gastroenterol 2001;36:1030–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghoos YF, Maes BD, Geypens BJ, et al. Measurement of gastric emptying rate of solids by means of a carbon labeled octanoic acid breath test. Gastroenterology 1993;104:1640–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Notivol R, Coffin B, Azpiroz F, et al. Gastric tone determines the sensitivity of the stomach to distention. Gastroenterology 1995;108:330–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarnelli G, Caenepeel P, Geypens B, et al. Symptoms associated with impaired gastric emptying of solids and liquids in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;98:783–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knill-Jones RP. Geographical differences in the prevalence of dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1991;182:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talley NJ. Review article: functional dyspepsia - should treatment be targeted on disturbed physiology? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1995;9:107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tack J, Caenepeel P, Degreef A, et al. Symptom severity and subtypes in functional dyspepsia: Rome II criteria or a pathophysiological approach? Gastroenterology 2000;118:A619. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koch KL, Hong SP, Xu L. Reproducibility of gastric myoelectrical activity and the water load test in patients with dysmotility-like dyspepsia symptoms and in control subjects. J Clin Gastroenterol 2000;31:125–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tosetti C, Salvioli B, Stanghellini V, et al. Reproducibility of a water load test in health subjects and symptom profile compared to patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 1999;116:A336. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boeckxstaens G, Hirsch DP, Van Den Elzen BD, et al. Impaired drinking capacity in patients with functional dyspepsia: relationship with proximal stomach function. Gastroenterology 2001;121:1054–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Read N, French S, Cunningham K. The role of the gut in regulating food intake in man. Nutr Rev 1994;52:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavin JH, Wittert G, Sun WM, et al. Appetite reulation by carbohydrate: role of blood glucose and gastrointestinal hormones. Am J Physiol 1996;281:E209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matzinger D, Gutzwiller JP, Drewe J, et al. Inhibition of food intake in response to intestinal lipid is mediated by cholecystokinin in humans. Am J Physiol 1999;277:R1718–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tack J. Drink tests in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2002;122:2093–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heddle R, Dent J, Read NW, et al. Antropyloroduodenal motor responses to intraduodenal lipid infusion in healthy volunteers. Am J Physiol 1988;254:G671–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piessevaux H, Dewit O, Tack J, et al. Intragastric distribution pattern of a liquid meal during satiety testing in healthy volunteers. Gastroenterology 2000;118:A670. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruley des Varannes S, Parys V, Ropert A, et al. Erythromycin enhances fasting and postprandial proximal gastric tone in humans. Gastroenterology 1995;109:32–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tack J, Broeckaert D, Coulie B, et al. Influence of cisapride on gastric tone and on the perception of gastric distension. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998;12:761–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coulie B, Tack J, Broekaert D, et al. Motor patterns underlying the delay in gasric emptying during 5-HT1 receptor activation in man. Gastroenterology 1997;110:A715. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coulie B, Tack J, Maes B, et al. Sumatriptan, a selective 5-HT1 receptor agonist, induces a lag phase for gastric emptying of liquids in humans. Am J Physiol 1997;272:G902–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tack J, Coremans G, Janssens J. A risk-benefit appraisal of cisapride in the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. Drug Saf 1995;12:384–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janssens J, Peeters TL, Vantrappen G, et al. Improvement of gastric emptying in diabetic gastroparesis by erythromycin. Preliminary studies. N Engl J Med 1990;322:1028–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]