Abstract

Background and aims: In neonates the gastrointestinal tract is exposed to food and bacterial antigens at a time when the gut mucosal immune system has not developed the ability to induce oral tolerance. This increases the risk for an inappropriate immune response to oral antigens. Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) is an immunoregulatory cytokine present in high concentration in maternal milk. Interleukin 18 (IL-18) is a cytokine that mediates early immune events, and drives T cell development. We assessed the role of TGF-β in mediating mucosal immune development and specifically the effect on endogenous IL-18.

Methods: Rat pups were randomly assigned to the following groups, naturally suckled, maternal milk via cannula, and formula fed with and without physiological levels of TGF-β2. A comparison of the immune response profile was then carried out. Cytokine profiles, dendritic cell, intestinal mast cell, and eosinophil numbers were assessed.

Results: We show that feeding formula deficient in TGF-β2 resulted in accumulated IL-18 protein release from intestinal epithelial cells and IL-18 mRNA up regulation. A proinflammatory cytokine profile resulted in the gut, along with increased numbers of activated dendritic cells, eosinophils, and mast cells. Supplementation of the formula with TGF-β2 down regulated the proinflammatory cytokine mRNA as well as the number of activated lymphocytes, eosinophils, mast cells, CD80, and CD86 positive dendritic cells.

Conclusion: The data suggests an important role for maternal milk, in regulating immune responses after exposure to food antigens, which might otherwise induce deleterious immune responses in the intestine of suckling neonates. This regulation is potentially mediated by milk TGF-β2, as well as endogenous IL-18.

Keywords: milk, TGF-β, IL-18, immune development

The gastrointestinal tract is exposed to an enormous antigenic load on a daily basis. The mucosal immune system mounts an active immune response to oral antigen exposure which can lead to tolerance induction in the periphery, thereby reducing the risk of a harmful response to food antigens. Oral tolerance can be induced by several mechanisms: anergy, receptor down regulation, or active cellular suppression. The generation of suppressor or regulator cells and the cytokine environment in which antigens are processed are critical to the maintenance of normal homeostasis in the intestine.1 In neonates, the gastrointestinal tract is exposed to food, bacterial, and environmental antigens at a time when he gut mucosal immune system has not developed the ability to induce oral tolerance.2 This increases the risk for an inappropriate immune response to oral antigen.

Indirect evidence suggests that maternal milk components regulate mucosal immune activity to luminal antigens in suckling infants.3,4 Development of autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes and Crohn’s disease show an inverse correlation with breast feeding in infancy, and formula fed infants have an increased susceptibility to immune hypersensitivity.5,6

At present little is known about the components of milk that influence immune reactivity in the suckling period. The cytokine environment in which antigens are first encountered after birth influences subsequent encounters with antigens.7,8 Cytokines in milk, such as interleukin 10, interleukin 4 and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) influence antigen priming. TGF-β is one of the prime immuno-downregulatory cytokines involved in tolerance induction, and is present in high concentration in maternal milk.9–11 The importance of neonatal exposure to TGF-β in breast milk is highlighted by TGF-β knockout mice which appear healthy when suckled on TGF-β producing mothers, but do not survive after weaning due to an uncontrolled inflammatory state.12,13 We have shown that TGF-β2 is present in significant concentration in maternal rat milk14 and that TGF-β receptors are present in the neonatal gut.15,16

Interleukin 18 (IL-18) is a mediator of innate and acquired immunity, triggering early immune events and promoting interferon γ (IFN-γ) production as well as driving T helper cell type 1 (Th1) development. IL-18 influences Th1 or T helper cell type 2 (Th2) development depending on the cytokine milieu at the time of antigen priming.17,18 IL-18 is produced by a number of cell types including macrophages, dendritic cells, and intestinal epithelial cells. Dendritic cells constitutively produce IL-18 and in response to specific T cell stimuli they dramatically modulate this synthesis and secretion, supporting the role of IL-18 in the early phase of defence by the immune system.19 Enterocyte IL-18 is up regulated in Th1 associated diseases such as Crohn’s disease.20

In formula fed infants the potential for inappropriate immune development to oral antigen exposure is increased, as the cytokine milieu provided by breast milk is not present to help immunoregulate. Our hypothesis is that maternal milk TGF-β regulates IL-18 stimulated immune responses to early antigen exposure.

METHODS

Animals

Pregnant in bred Hooded Wistar rats were obtained from the Women’s and Children’s Hospital breeding colony (North Adelaide, Australia). The study was carried out with the approval of the Women’s and Children’s Hospital Animal Ethics Committee, Adelaide, Australia.

Cannulation and maintenance procedure

We have previously described the model and surgical procedure.21 Rat pups from several different litters were randomly assigned to the naturally suckled, formula fed, maternal milk via cannula, or the TGF-β2 supplemented animal groups. The technical staff who allocated animals to the groups were independent from the researchers conducting the experiments. Each group of rats was composed of a mix of pups from different litters. The mix of rats in a group was such that within a group, some rats were from the same litter and others were from different litters. In bred rats significant variation between litters is not expected, however the model has been designed to minimise any potential variation that may exist.

When the pups were 4 days old, a water lubricated length of silastic tubing (0.51 mm) was introduced into the mouth of each pup and into the stomach. The pups were then anaesthetised using Forthane (Isoflurathane, Abbott, Australia) and an intragastric cannula implanted. A broad spectrum antibiotic, benzylpenicillian sodium 600 mg (CSL, Melbourne, Australia), was placed on all surgical wounds and each pup placed in a polystyrene cup with bedding. The cups were placed in a water bath at 42°C to ensure that the pups maintained body temperature. The cannula was connected to a polyethylene milk line (single lumen polyethylene tube, PE-45,OD 0.96 mm, ID 0.58 mm Critchley Electrical Products Silverwater, NSW, Australia), that was attached to a 23 gauge needle on a syringe containing formula (Rat Milk Replacer, Wombaroo, Adelaide, Australia22), mounted on a Multi-syringe infusion pump (SDR Clinical Technology, Middle Cove, NSW, Australia). The infusion pumps were placed in a refrigerator at 4°C to prevent spoilage of the milk. Changes in intestinal parameters in artificially reared rat pups have been directly attributed to the formula and not to the surgical procedure itself, as maternal milk fed via cannula results in no physiological changes in the intestine when compared to naturally suckled pups.23

Experimental design

Four groups of animals were used in the experiment. To determine the minimum number of animals required for each group a power calculation was carried out. All animals which started the experiment finished the experiment—that is, no adverse events occurred. Naturally suckled animals were used as the reference group. Formula fed rat pups were given either bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a vehicle control (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA), or rTGF-β2 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) +0.1% BSA carrier protein as a continuous infusion of 100 ng/ml of formula. A physiological concentration of TGF-β2 was used in the experiment (100 ng/ml) equivalent to the amount of TGF-β2 found in mid-lactation rat milk.14 We assessed a physiological concentration of TGF-β2, as it was not possible to do a dose range due to the high cost of rTGF-β2. No bioactive TGF-β was detected in the formula as assessed by inhibition of proliferation of the CCL-64 Mv1Lu epithelial cell line.16 Formula fed pups consumed approximately 4–5 ml of formula on days four to six, 6–10 ml on days seven to 10, and up to 12 ml on days 11 to 14. Pups that did not receive at least 90% of their required formula intake or showed any obvious sign of infection were excluded from the trial. Weight gain did not significantly differ between groups over the course of the experiment. A fourth group of rat pups fed maternal milk via cannula was also included. The objectives were to compare the immune response profile after formula feeding with that in naturally suckled animals and those fed formula supplemented with TGF-β2. Animal trials and analysis of data were completed in a 2.5 year period.

Rat pups were killed at 14 days old and the gastrointestinal tract excised. Small intestinal tissue was isolated and either embedded in medium for frozen tissue (TissueTek, Sakura Finetek, USA) and cooled by liquid nitrogen, or fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde (pH 7.0) for 24 h and then embedded in paraffin. The pups’ distal ileum were collected and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for protein and RNA analysis. Analysis of the experimental outcomes below, were carried out in a blinded manner where the person doing the analysis knew the pup’s number but not the group to which the pup belonged.

Immunohistochemical analyses were carried out on segments of the ileum. Three micrometre sections were cut from paraffin embedded tissue and placed on gelatin coated slides. Sections were deparaffinised, rehydrated, and incubated in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% saponin, 1% fetal calf serum (FCS) PBS containing 0.1% saponin, 1% FCS for 15 min. Sections were washed in PBS and incubated with 1% normal goat Ig (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at room temperature to block non-specific binding. The blocking antibody was decanted and 100 μl of a 1/250 dilution of goat anti-IL-18 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. California, USA) added, and the sections incubated overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed twice in PBS containing 0.1% saponin, 1% FCS for 5 min each wash, and blocked with 100 μl of 1% normal rabbit serum (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min, followed by biotinylated rabbit antigoat IgG (H+L) (Sigma-Aldrich) and the sections incubated for 60 min. The sections were washed in PBS containing 0.1% saponin and 1% FCS for 15 min, followed by two washes in Tris-buffered-saline (TBS) pH 7.4. Streptavidin-Cy3 (Jackson Laboratories, PA, USA) was added and the sections incubated for 30 min in the dark then washed and mounted in fluorescence mounting media (Dako, Carpenteria, CA, USA). All antibody dilutions were made in 0.2% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) in TBS. Controls included: (1) sections incubated with normal goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich) added as the primary antibody in place of the goat anti-IL-18. (2) Sections incubated with secondary antibody prior to indocarbocyanine (Cy3) labelling only. (3) Sections incubated with primary antibody, goat anti-IL-18 which had been preincubated with 10 ng/ml rIL-18 (Santa Cruz) for 20 min on ice to neutralise anti IL-18 activity. Sections were examined for fluorescent labelled cells with a Leica microscope (Leitz DMRB, Wetzlar, Germany) at 400× magnification. Image Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Maryland, USA) was used to capture images of intestinal sections.

Immunofluorescent labelling of cell surface markers in the intestine

Serial cryostat sections (8 μm) were cut and stained for either CD2 or CD25 as previously described.15 Mouse anti-rat-CD2 (OX-54, Serotec, Oxford, UK) or mouse anti-rat-CD25 (NDS-61, anti IL-2R alpha chain antibody, Serotec) were used as primary antibodies. Sections were incubated with anti-CD2 or anti-CD25 at room temperature for 1 h then washed with PBS followed by incubation with biotin conjugated horse antimouse (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 1 h. After washing, Streptavidin-Cy3 (Jackson Laboratories, Maine, USA) was added and the sections incubated in the dark for 30 min. Sections were examined for fluorescent cells with a Leica microscope at 400× magnification. Four sections of intestine per animal were assessed, with each section containing an entire “doughnut” of intestine. A minimum of 15 microscopic fields were analysed. On each microscopic field, the total area was measured by drawing a 1 pixel thick line around the lamina propria area of each villus and the fluorescent cells counted and expressed as cells per mm2.

Intestinal sections were also dual labelled for CD80 (B7.1) or CD86 (B7.2) expression on dendritic cells using a modification of our method for dual labelling, Zhang et al.15 On the same section, cells were dual labelled with antibody against CD80, a costimulatory marker and OX62 (Serotec24) a marker for dendritic cells, or CD86 (BD PharMingen, San Diego California) and OX62. Sections were incubated with anti-CD80 or CD86 as described above. After washing with PBS sections were incubated with biotin conjugated horse antimouse (Vector Laboratories) for 1 h and then washed. Streptavidin-Cy3 (Jackson) was added and the sections incubated in the dark for 30 min. After washing, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated anti-OX62 was added for a further 30 min. Sections were washed and mounted in fluorescence mounting media (DAKO) and examined for fluorescent cells as described above. The morphology of the labelled OX62 cells was assessed before including them in the count, as OX62 labels other cells including intraepithelial lymphocytes.24

Eosinophil and mast cell staining

Eosinophil and mast cell counts were carried out on segments of ileum. Three micrometre sections were cut from paraffin embedded tissue, and placed on gelatin coated slides. Sections were deparaffinised and rehydrated and routinely stained for mast cells which were identified by stained red granules using Leder chloroacetate esterase stain and eosinophils using Giemsa stain which stains eosinophil granules red/orange.

RNAse protection assay

Cytokine RNA was assessed in the ileum using the Riboquant multi-probe RNase protection assay system (BD Pharmingen). RNA was extracted using RNAzol B (Tel-Test, Friendswood, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions. In vitro transcription with 32P-labelled UTP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK) was performed using the relevant cytokine probe sets, and 20 μg of intestinal RNA according to the manufacturers’ instructions (BD Pharmingen). Dried gels were exposed to phosphorimaging screens and protected fragments visualised using a phosphorimager (Typhoon, Molecular Dynamics, Australia). Protected fragments were quantified and normalised with respect to the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

Western blot detection of IL-18

To extract proteins, ileum samples were homogenised on ice in lysis buffer (PBS pH 7.2, 1% Triton X100, 0.05% protease inhibitor cocktail for mammalian cell extracts (Sigma-Aldrich)) followed by 30 min incubation on ice. Homogenates were centrifuged twice at 10 000 g at 4°C for 20 min to collect supernatant. Protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, USA) and samples stored at −80°C until use. Gut lysates were diluted to 2.5 mg/ml in water and 75 μg of total protein lysates were separated on a 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen, Groningen, Netherlands). 5 ng of recombinant rat IL-18 (18.4kDa) (R&D Systems) was run as a positive control. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. IL-18 proteins were detected after incubation with biotinylated goat antirat IL-18 (R&D Systems) for 2 h at room temperature and subsequent incubation with avidin-horseradish peroxidase (Dako, USA). Bands were visualised using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

ELISA for serum rat mast cell protease II

Serum was collected from rat pups in each group and assessed for rat mast cell protease II (RMCPII) by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Moredun Scientific Ltd., Midlothian, UK).

STATISTICAL METHODS

Statistical evaluation of data in figures 1 ▶, 2 ▶, and 3 ▶ were performed using a Median Test. A Kruskal-Wallis test with a Dunn’s post-test was carried out on data in figure 4 ▶.

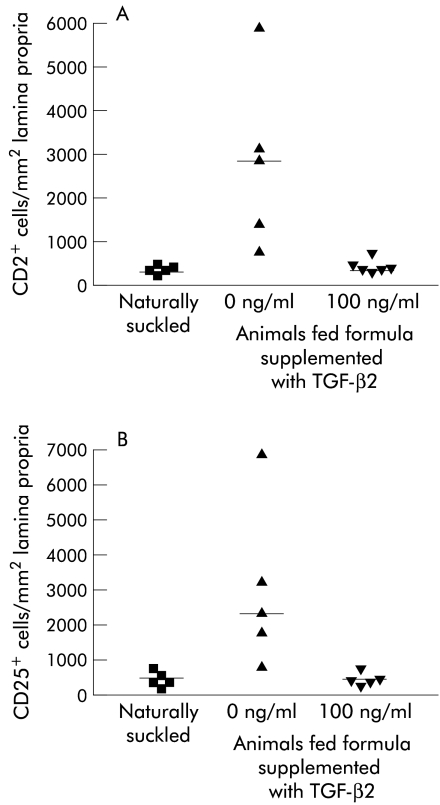

Figure 1.

Numbers of CD2+ and CD25+ cells in the ileum of naturally suckled (NS) and formula fed (FF) rat pups. (A) Number of CD2+ lymphocytes and (B) number of CD25+ cells in the lamina propria of the small intestine of rat pups either naturally suckled, formula fed, or fed formula supplemented with TGF-β2 at 100 ng/ml. Data from n=5–6 animals per group with the median indicated (—). Statistics: (A) a median test was carried out. NS v FF (median 595, p=0.008), FF v FF with 100 ng/ml TGF-β2, (median 667, p=0.026). (B) NS v FF (median 720, p=0.008), FF v FF with 100 ng/ml TGF-β2 (median 667, p=0.026).

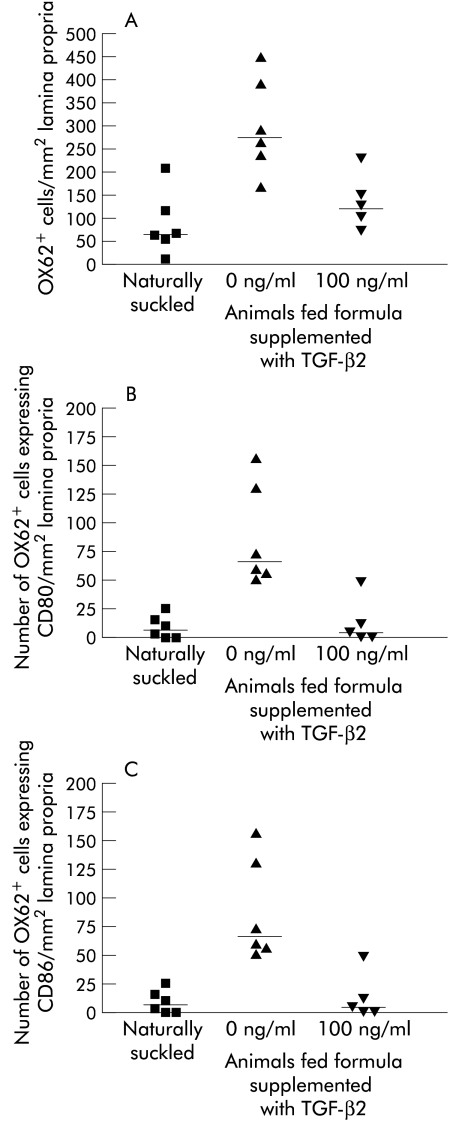

Figure 2.

Number of OX62+ dendritic cells, OX62+CD80+, and OX62+CD86+ dual labelled dendritic cells in intestine of naturally suckled (NS) and formula fed (FF) rat pups. Immunofluorescent labelling of OX62+ cells in the lamina propria of the small intestine of rat pups either NS, FF, or FF with 100 ng/ml of TGF-β2. Labelling of (A) total OX62+ cells. (B) Dual labelled OX62+ CD80+ cells. (C) Dual labelled OX62+CD86+ cells. Data from n=5–6 animals per group with the median indicated (—). Statistics: (A) NS v FF (median 187, p=0.08), FF v FF with 100 ng/ml TGF-β2 (median 229, p=0.08). (B) NS v FF (median 39.5, p=0.002), FF v FF with 100 ng/ml TGF-β2 (median 53, p=0.004). (C) NS v FF (median 102, p=0.002), FF v FF with 100 ng/ml TGF-β2, (median 108, p=0.004).

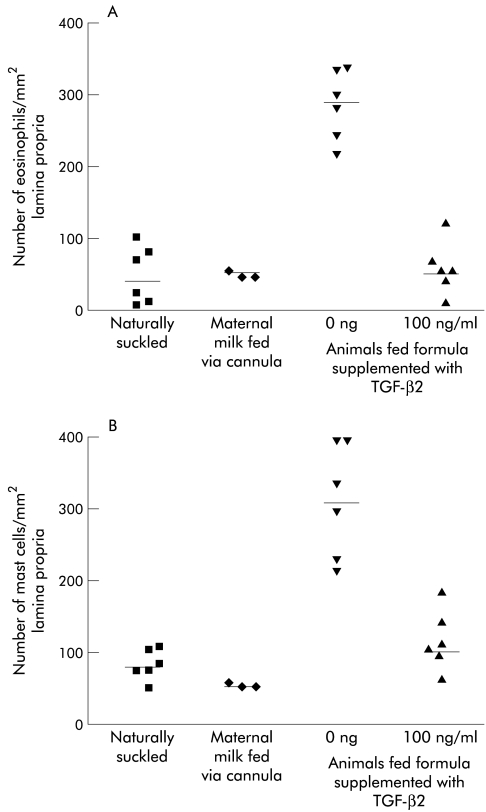

Figure 3.

Eosinophil and mast cell numbers in the ileum of naturally suckled (NS) and formula fed (FF) rat pups. Eosinophil (A) and mast cell (B) staining in the lamina propria of the small intestine of rat pups either NS, FF, FF supplemented with 100 ng/ml TGF-β2, or maternal milk fed via cannula (MMFC). Data is from n=5–6 animals per group, (except the MMFC group where n=3) with the median indicated (—). Statistics: (A) NS v FF (median 160, p=0.002), FF v FF with 100 ng/ml TGF-β2 (median 167, p=0.0022). (B) NS v FF (median 162, p=0.002), FF v FF with 100 ng/ml TGF-β2 (median 201, p=0.002).

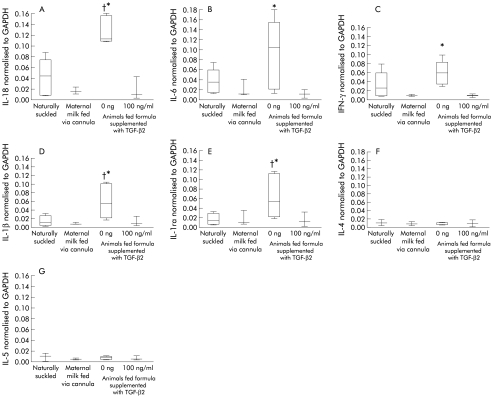

Figure 4.

Cytokine mRNA in the ileum of naturally suckled (NS) and formula fed (FF) rat pups. Cytokine mRNA expression in the small intestine of rat pups either NS, maternal milk fed via cannula (MMFC), FF, or FF supplemented with 100 ng/ml TGF-β2. (A) IL-18 mRNA, (B) IL-6 mRNA, (C) interferon γ (IFN-γ) mRNA, (D) IL-1β mRNA, (E) Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) mRNA, (F) IL-4 mRNA, (G) IL-5 mRNA. Cytokine mRNA levels were normalised to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Results represent the mean data from six animals per group, except for the MMFC group where there n=3 animals. The 25th and 75th percentiles with the median at the 50th are represented by the box, with highest and lowest values indicted by the whiskers. Statistics: (A) Kruskal-Wallis test: IL-18 p=0.0022, IL-6 p=0.0134, IFN-γ p=0.047, IL-1ra p=0.019, IL-1β p=0.0316, IL-5 p=0.16, and IL-4 p=0.46. Dunn’s post test: †NS v FF (p<0.05); *FF v FF with 100 ng/ml TGF-β2 (p<0.05).

RESULTS

Effect of TGF-β2 on CD2+ and CD25+ cells in the small intestine

To investigate whether formula feeding resulted in increased CD2+ T cell and CD25+ cell numbers, frozen sections of small intestine from naturally suckled pups and pups fed formula with and without TGF-β2 were examined for either CD2+ lymphocytes (figure 1A ▶) or CD25+ cells (figure 1B ▶). CD2+ and CD25+ cell numbers were low in naturally suckled pups, and high in formula fed animals. TGF-β2 supplementation of formula cancelled out this increase in CD2+ cells and CD25+ positive cells.

Effect of TGF-β2 on dendritic cells in the intestine

We also assessed dendritic cells and the expression of costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 which are increased upon antigen presentation. In the intestine of naturally suckled rat pups the number of dendritic cells (OX62+ cells) in the lamina propria was low, with only a few cells positive for CD80 (9.6 (SD) (4.2) cells/mm2), and more expressing CD86 (50.5 (12.7) cells/mm2) (figure 2 ▶). There was a significant increase in OX62/CD80 and OX62/CD86 positive dendritic cells in the intestine after formula feeding. Total dendritic cell numbers in the intestine did not vary significantly between the groups. Supplementation of the formula with TGF-β2 resulted in a significant decrease in the number of dendritic cells staining positive for CD80 and CD86 costimulatory molecules, with a greater inhibition of CD80 positive cells than CD86.

Eosinophil and mast cell infiltration in the ileum

Eosinophil and mast cell infiltration is associated with cow’s milk allergy in human infants. The data in figure 3 ▶ show that there was a significant increase in both eosinophil (figure 3A ▶) and mast cell (figure 3B ▶) numbers after formula feeding when compared to naturally suckled animals. TGF-β2 supplementation of formula resulted in a significant decrease in eosinophils and mast cells. Maternal milk fed via cannula resulted in no significant differences in mast cell or eosinophil numbers when compared to naturally suckling rat pups.

We also found a significant increase in serum RMCPII concentration, a marker for mucosal mast cell activation, in formula fed rat pups (46.5 (SD) (8) ng/ml) compared to naturally suckled animals (25.7 (3) ng/ml). TGF-β2 supplementation partially normalised RMCPII concentration (37.4 (5) ng/ml).

Expression of cytokine mRNA in the intestine

To determine if formula feeding influenced the gut mucosal cytokine profile, we assessed intestinal mRNA expression (figure 4 ▶). The data in figure 4 ▶ show that IL-18, and interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) mRNA in the ileum were significantly increased in formula fed rat pups compared to naturally suckled pups. TGF-β2 supplementation of formula resulted in a significant decrease in IL-18, and IL-1ra mRNA compared to rat pups fed unsupplemented formula. IFN-γ and interleukin 6 (IL-6) mRNA in the intestine of naturally suckled rat pups were not significantly different from formula fed rat pups, however supplementation of formula with TGF-β2 significantly reduced IL-6 and IFN-γ mRNA. Interleukin 4 (IL-4) and interleukin 5 (IL-5) mRNA levels were very low with no significant difference between the three animal groups. The cytokine mRNA profile after feeding maternal milk via cannula was not significantly different from that seen in naturally suckled rat pups for all cytokines assayed.

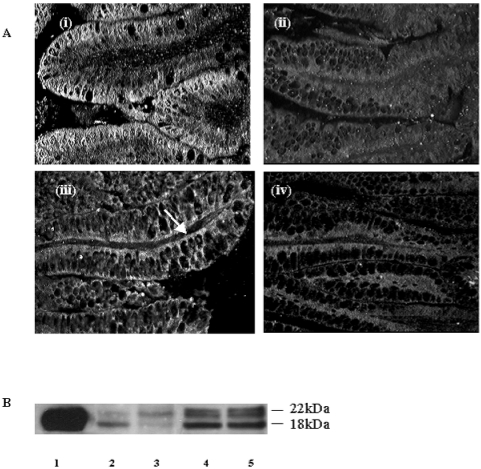

Expression of IL-18 protein in the intestine

IL-18 was assessed in the intestine by immunofluorescence (figure 5A ▶) and western blot analysis (figure 5B ▶). IL-18 was detected in epithelial cells of the villi in the ileum of naturally suckled rat pups, where strong and diffuse staining was present. Some staining was seen in scattered cells in the lamina propria (figure 5A ▶(i)). No IL-18 staining was detected in epithelial cells in the ileum of rat pups reared on formula (figure 5A ▶(ii)). Feeding formula supplemented with 100 ng/ml TGF-β2 resulted in a partial restoration of IL-18 labelling particularly on the basolateral membrane of the enterocytes (figure 5A ▶(iii)). Control sections from naturally suckled rat pups in which the antibody to the IL-18 had been pre-absorbed with blocking peptide were negative for IL-18 staining (figure 5A ▶(iv)).

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescent and western blot detection of IL-18 in the neonatal intestine of naturally suckled and formula fed rat pups. (A) Immunofluorescent labelling of IL-18 in ileum of rat pups either (i) naturally suckled (ii) fed unsupplemented formula (iii) fed formula supplemented with 100 ng/ml TGF-β2, and (iv) negative control with anti-IL-18 pre-absorbed with rIL-18 (magnification 400×). (B) Western blot staining of IL-18 in rat ileum. Lane 1: recombinant IL-18. Lane 2: ileum from formula fed rat pup. Lane 3: ileum from pup fed formula with 100 ng/ml TGF-β. Lane 4: ileum from pup fed maternal milk via cannula. Lane 5: ileum from a naturally suckled rat pup.

By western blot analysis, the mature active form of IL-18 (18kDa) as well as low levels of the precursor form (22kDa) were detected in the intestines of formula fed rat pups. In pups fed formula supplemented with TGF-β2 there was more of the IL-18 precursor form than the mature form. In naturally suckled pups and pups fed maternal milk via cannula, both the precursor form and active IL-18 were detected.

DISCUSSION

The data in this study provides evidence of a role for maternal milk in directing immune development in suckling infants. This immune regulation is potentially mediated by TGF-β. Our results are consistent with formula feeding leading to release of stockpiled IL-18 from enterocytes, as well as induction of IL-18 mRNA in the small intestine. An increased immune cell infiltrated occurred in the intestine of formula fed rat pups. This inflammatory response was down regulated by supplementation of formula with TGF-β. Taken together, these findings emphasise the importance of TGF-β in breast milk preventing an exaggerated early immune response to oral antigens before oral tolerance has fully developed.

Weaning in both rodents and humans is associated with immune activation, which rapidly decreases over 48 h.25,26 Lymphocyte activation has also been reported in human infants with cow’s milk allergy.27 Early formula feeding might be expected to exaggerate these responses, as during this early neonatal period critical immunoregulatory mechanisms are not developed enough to induce oral tolerance. Consistent with this we show an increased immune response after formula feeding. The potential for antigen presentation is increased by high numbers of activated dendritic cells expressing CD80 and CD86 (figure 2 ▶), and increased expression of CD25 on cells in the lamina propria of formula fed rat pups (figure 1 ▶). CD2+ cells were assessed as lamina propria cells are reported to have an enhanced responsiveness to cytokines when stimulated through CD2.28 TGF-β and also IL-10 secreting cells are thought to be responsible for maintaining normal homeostasis in the gut by creating a cytokine milieu for appropriate antigen processing and oral tolerance.1 We have previously shown that TGF-β levels are high in maternal rat milk after birth, whereas endogenous levels of TGF-β in the intestine are low at birth and increase toward weaning.14 In naturally suckling animals the gut is exposed to maternal milk cytokines, which help regulate immune responses until the gut has matured by weaning age to produce its own immunoregulatory cytokines for normal gut homeostasis. In the absence of maternal milk cytokines (that is, formula feeding) the potential for immune activation to oral antigens would be increased. This is further highlighted by the data from TGF-β knockout mice. When suckled on heterozygous mothers they appear normal due to “maternal rescue” with milk derived TGF-β, but die from a widespread inflammatory reaction a few weeks after weaning when maternal milk is no longer present.12

Dendritic cells are antigen presenting cells with the unique ability to activate naïve T cells and they are involved in tolerance induction by promoting TGF-β production in the gut after antigen exposure.29 Furthermore TGF-β itself suppresses dendritic cell maturation.30 CD80 and CD86 are essential for activation of T cells and the absence or low levels of these costimulatory molecules results in T cell deletion or anergy.31 In normal mucosa CD86 expression is low, whereas in inflamed mucosa CD80 and CD86 positive macrophages are increased.32 Our finding of low numbers of CD80 and CD86 positive dendritic cells in the gut of naturally suckled rat pups is consistent with the gut mucosal immune system being in a quiescent, down regulated state. CD86 is required for tolerance induction, whereas CD80 has no effect on tolerance but is associated with activation of Th1 cells and a pro-inflammatory cytokine response.33 Formula feeding resulted in a significant increase in dendritic cells expressing CD80 and CD86 in the lamina propria with a greater increase in CD80 positive cells, thereby increasing the potential for a pro-inflammatory immune response. Down regulation of dendritic cell numbers and CD80 and CD86 expression by TGF-β supplementation at the same concentration as found in maternal milk, suggests that TGF-β in milk accounts for at least part of the immunomodulatory activity of milk. To further define this immunoregulatory role it would be ideal to deplete TGF-β from maternal milk and feed this to rat pups via cannula. This was not feasible as the resulting mixture would not support the nutritional requirements of the rat pups. However, the data from TGF-β knockout mice as discussed above, strongly supports a role for milk derived TGF-β in infant immune regulation.12

IL-18 is an important immunoregulatory cytokine for both Th1 and Th2 responses.18 Only the mature form of IL-18 is bioactive, whereas pro-IL-18 is inactive.34 We show that IL-18 is constitutively produced and stored by intestinal epithelial cells in naturally suckled rat pups in support of the study of Takeuchi et al.35 Constitutive IL-18 expression has also been reported in other antigen presenting cells.17,36 Stored active IL-18 maybe required to maintain the background level of IFN-γ present in the naturally suckled rat pup intestine (figure 4 ▶). Stored IL-18 would allow for a quick immune response when needed, and the promotion of innate as well as specific immunity. After formula feeding, detection of IL-18 protein was dramatically reduced in the intestine with more active IL-18 (18kDa) form detected (figure 5 ▶). TGF-β2 supplementation, partially restored detectable IL-18 protein in the intestine (figure 5A ▶(iii)), with increased pro-form detected (figure 5B ▶), supporting a role for this cytokine in maintaining homeostasis. No difference was seen in IL-18 assessed by western blot analysis of the intestine between rat pups which were either naturally suckled or fed maternal milk via cannula. This supports the findings of Dvorak et al23 who attributed changes in the intestine after formula feeding directly to the formula and not the cannulation procedure. Furthermore, feeding maternal milk via cannula did not significantly influence other intestinal cytokine mRNA, or eosinophil and mast cell numbers.

Kampfer et al,37 report on the counter regulation of IL-18 in vivo and in vitro. We see a similar phenomenon in our experiments, where an increase in IL-18 protein levels was directly associated with a down regulation of IL-18 mRNA, (figures 4 ▶ and 5 ▶). Antigen exposure also induces release of accumulated endogenous IL-18 from antigen presenting cells, which is then followed by a very rapid uptake and processing of IL-18 by T cells in the surrounding environment.19,36 In formula fed rat pups the IL-18 released from epithelial cells is presumably rapidly taken up and processed by T cells in the lamina propria. Similar findings on the release and absence of IL-18 protein labelling in intestinal epithelial cells after helminth infection has also recently been reported.38

In addition to IL-18, IL-1β mRNA was also elevated after formula feeding. TGF-β2 supplementation down-regulated these cytokines as well as IFN-γ and IL-6 mRNA (figure 4 ▶). IL-6 is known to regulate CD25 expression on cells.39 We show a decreased expression of CD25 on lamina propria cells after TGF-β2 supplementation when IL-6mRNA levels are low. IL-4 and IL-5 mRNA levels were very low and not significantly different between the three groups. The data therefore suggests that there is an up regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines after antigen encounter in the absence of immunoregulatory cytokines derived from maternal milk. IL-1ra mRNA was also elevated in formula fed pups and again supplementation of formula with TGF-β2 resulted in levels similar to that observed in naturally suckled pups. IL-1ra release during inflammation is thought to be a mechanism to limit the effects of IL-1.40 IL-1β and IL-1ra together with IL-18 play important roles in regulation of acute inflammation.

Our finding of mast cell and eosinophil infiltration in the gut of formula fed rat pups is consistent with the aberrant immune response seen in food hypersensitivity reactions in human infants.27 Furthermore this infiltration was inhibited by TGF-β. No significant difference between IL-4 and IL-5 mRNA levels were observed in rat pups naturally suckling and those fed formula supplemented with TGF-β2. This suggests that TGF-β2 inhibits infiltration of eosinophils and mast cells into the intestine independent of IL-5 or IL-4 down regulation. Similar findings have been reported by others, who show that TGF-β secreted by T cells reduce antigen induced eosinophil inflammation at mucosal sites and induced tolerance.41 We also found a significant increase in serum RMCPII concentration, a marker for mucosal mast cell activation, in formula fed rat pups.

The data outlined in this study suggests an important role for maternal milk, in down regulating the immune response after exposure to food antigens, which might otherwise induce harmful immune responses in the intestine of suckling neonates. This regulation of mucosal immune response development is potentially mediated by milk TGF-β2, as well as endogenous IL-18.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Adrian Cummins for his helpful comments and Mr Callum Gillespie, Ms Kerry Penning, and Ms Jade Duncan for excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

BSA, bovine serum albumin

Cy3, indocarbocyanine

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

IFN-γ, interferon γ

IL-18, interleukin 18

IL-1ra, interleukin 1 receptor antagonist

PBS, phosphate buffered saline

RMCP II, rat mast cell protease II

TGF-β, transforming growth factor β

Th1, T helper cell type 1

Th2, T helper cell type 2

This work was carried out with the support of the NH&MRC, Channel 7 Research Foundation and the CRC-Tissue Growth and Repair.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weiner HL. The mucosal milieu creates tolerogenic dendritic cells and T(R)1 and T(H)3 regulatory cells. Nat Immunol 2001;2:671–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strobel S, Ferguson A. Immune responses to fed protein antigens in mice 3. Systemic tolerance or priming is related to age at which antigen is first encountered. Pediatr Res 1984;18:588–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carver JD. Dietary nucleotides: effects on the immune and gastrointestinal systems. Acta Paediatr Suppl 1999;88:83–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn-Zoric M, Fulconis F, Minoli I, et al. Antibody responses to parenteral and oral vaccines are impaired by conventional and low protein formulas as compared to breast-feeding. Acta Paediatr Scand 1990;79:1137–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayer EJ, Hamman RF, Gay EC, et al. Reduced risk of IDDM among breast-fed children. The Colorado IDDM Registry. Diabetes 1988;37:1625–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koletzko S, Sherman P, Corey M, et al. Role of infant feeding practices in development of Crohn’s disease in childhood. BMJ 1989;298:1617–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh RR, Hahn BH, Sercarz EE. Neonatal peptide exposure can prime T cells and, upon subsequent immunization, induce their immune deviation: implications for antibody vs T cell-mediated autoimmunity. J Exp Med 1996;183:1613–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pabst HF, Godel J, Grace M, et al. Effect of breast-feeding on immune response to BCG vaccination. Lancet 1989;1:295–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito S, Yoshida M, Ichijo M, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) in human milk. Clin Exp Immunol 1993;94:220–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudloff HE, Schmalstieg FC Jr, Palkowetz KH, et al. Interleukin-6 in human milk. J Reprod Immunol 1993;23:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garofalo R, Chheda S, Mei F, et al. Interleukin-10 in human milk. Pediatr Res 1995;37:444–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Letterio JJ, Geiser AG, Kulkarni AB, et al. Maternal rescue of transforming growth factor-beta 1 null mice. Science 1994;264:1936–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Letterio JJ, Geiser AG, Kulkarni AB, et al. Autoimmunity associated with TGF-beta1-deficiency in mice is dependent on MHC class II antigen expression. J Clin Invest 1996;98:2109–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penttila IA, van Spriel AB, Zhang MF, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta levels in maternal milk and expression in postnatal rat duodenum and ileum. Pediatr Res 1998;44:524–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang MF, Zola H, Read LC, et al. Localization of transforming growth factor-beta receptor types I, II, and III in the postnatal rat small intestine. Pediatr Res 1999;46:657–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang M, Zola H, Read L, et al. Identification of soluble transforming growth factor-beta receptor III (sTbetaIII) in rat milk. Immunol Cell Biol 2001;79:291–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakanishi K, Yoshimoto T, Tsutsui H, et al. Interleukin-18 is a unique cytokine that stimulates both Th1 and Th2 responses depending on its cytokine milieu. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2001;12:53–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu D, Trajkovic V, Hunter D, et al. IL-18 induces the differentiation of Th1 or Th2 cells depending upon cytokine milieu and genetic background. Eur J Immunol 2000;30:3147–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardella S, Andrei C, Costigliolo S, et al. Interleukin-18 synthesis and secretion by dendritic cells are modulated by interaction with antigen-specific T cells. J Leukoc Biol 1999;66:237–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanai T, Watanabe M, Okazawa A, et al. Interleukin-18 and Crohn’s disease. Digestion 2001;63(Suppl 1):37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howarth GSCJ, Read LC, Butler RN, et al. Physiological, histological and immunological characterisation of a rat model of prematurity. Gastroenterology 2002;122:T1326. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oftedal OT, Iverson SJ. Handbook of milk composition. Sydney Australia: Academic Press, 1995:790–827.

- 23.Dvorak B, McWilliam DL, Williams CS, et al. Artificial formula induces precocious maturation of the small intestine of artificially reared suckling rats. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000;31:162–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brenan M, Puklavec M. The MRC OX-62 antigen: a useful marker in the purification of rat veiled cells with the biochemical properties of an integrin. J Exp Med 1992;175:1457–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masjedi M, Tivey DR, Thompson FM, et al. Activation of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue with expression of interleukin-2 receptors that peaks during weaning in the rat. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1999;29:556–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson FM, Catto-Smith AG, Moore D, et al. Epithelial growth of the small intestine in human infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1998;26:506–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung HL, Hwang JB, Kwon YD, et al. Deposition of eosinophil-granule major basic protein and expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in the mucosa of the small intestine in infants with cow’s milk-sensitive enteropathy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;103:1195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Targan SR, Deem RL, Liu M, et al. Definition of a lamina propria T cell responsive state. Enhanced cytokine responsiveness of T cells stimulated through the CD2 pathway. J Immunol 1995;154:664–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akbari O, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Pulmonary dendritic cells producing IL-10 mediate tolerance induced by respiratory exposure to antigen. Nat Immunol 2001;2:725–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strobl H, Knapp W. TGF-beta1 regulation of dendritic cells. Microbes Infect 1999;1:1283–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lenschow DJ, Walunas TL, Bluestone JA. CD28/B7 system of T cell costimulation. Annu Rev Immunol 1996;14:233–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rugtveit J, Bakka A, Brandtzaeg P. Differential distribution of B7.1 (CD80) and B7.2 (CD86) costimulatory molecules on mucosal macrophage subsets in human inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Clin Exp Immunol 1997;110:104–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L, Kuchroo VK, Weiner HL. B7.2 (CD86) but not B7.1 (CD80) costimulation is required for the induction of low dose oral tolerance. J Immunol 1999;163:2284–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fantuzzi G, Reed DA, Dinarello CA. IL-12-induced IFN-gamma is dependent on caspase-1 processing of the IL-18 precursor. J Clin Invest 1999;104:761–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takeuchi M, Nishizaki Y, Sano O, et al. Immunohistochemical and immuno-electron-microscopic detection of interferon-gamma-inducing factor (“interleukin-18”) in mouse intestinal epithelial cells. Cell Tissue Res 1997;289:499–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gardella S, Andrei C, Poggi A, et al. Control of interleukin-18 secretion by dendritic cells: role of calcium influxes. FEBS Lett 2000;481:245–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kampfer H, Kalina U, Muhl H, et al. Counter regulation of interleukin-18 mRNA and protein expression during cutaneous wound repair in mice. J Invest Dermatol 1999;113:369–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helmby H, Takeda K, Akira S, et al. Interleukin (IL)-18 promotes the development of chronic gastrointestinal helminth infection by downregulating IL-13. J Exp Med 2001;194:355–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romagnani S. T-cell subsets (Th1 versus Th2). Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2000;85:9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwab JH, Anderle SK, Brown RR, et al. Pro- and anti-inflammatory roles of interleukin-1 in recurrence of bacterial cell wall-induced arthritis in rats. Infect Immun 1991;59:4436–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haneda K, Sano K, Tamura G, et al. TGF-beta induced by oral tolerance ameliorates experimental tracheal eosinophilia. J Immunol 1997;159:4484–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]