Abstract

Background: Individuals with first degree relatives affected with colorectal cancer (CRC) at a young age, or more than one relative affected but who do not fulfil the Amsterdam criteria for a diagnosis of hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC), are believed to be at an increased risk of CRC. However, there is a paucity of prospective data on the potential benefit of colonoscopic surveillance in such groups categorised by empiric family history criteria. We report a prospective study of 448 individuals seeking counselling about their perceived family history of CRC.

Patients and methods: Following pedigree tracing, verification, and risk assignment by genetic counsellors, colonoscopy was undertaken for those at a moderate or high risk (HNPCC). Those classified as low risk were reassured and discharged without surveillance. Here we report our findings at the prevalence screen in the 176 patients of the 448 assessed who underwent colonoscopy.

Results: Fifty three individuals had a family history that met Amsterdam criteria (median age 43 years) and 123 individuals were classed as moderate risk (median age 43 years). No cancers were detected at colonoscopy in any group. Four individuals (8% (95% confidence limits (CL) 0.4–15%)) in the high risk group had an adenoma detected at a median age of 46 years and all four were less than 50 years of age. Five (4% (95% CL 0.6– 8%)) of the moderate risk individuals had an adenoma at a median age of 54 years, two of whom were less than 50 years of age.

Conclusions: These findings indicate that the prevalence of significant neoplasia in groups defined by family history is low, particularly in younger age groups. These prospective data call into question the value of colonoscopy before the age of 50 years in moderate risk individuals.

Keywords: familial colorectal cancer, risk assessment, screening, adenomas, genetic counselling

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most frequently diagnosed cancer in Scotland in both males and females.1 There can be an increased risk to relatives of an affected individual and a heightened awareness of this familial risk of CRC is resulting in an increasing number of individuals, concerned about their risk of CRC, enquiring about screening techniques/preventative measures. Regular colonoscopic surveillance is recommended in individuals at risk of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) as it has been shown that removal of polyps and adenomas during colonoscopy reduces the incidence of bowel cancer.2–4 However, only a minority of families have an identifiable hereditary predisposition syndrome such as HNPCC or familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). There is a larger less well defined cohort of people with a lesser degree of family history where screening recommendations vary considerably geographically. This variation could be due to a current lack of published information supporting the possible benefit, or frequency, of colonoscopic surveillance in such groups.5–7

Recommendations for colonoscopic screening of asymptomatic people with a familial risk of CRC were published in Scotland in 2001 (table 1 ▶). These Scottish Office approved guidelines were devised following an evidence based medicine approach and, because of a lack of published information, national consensus discussion.8,9 Furthermore, these pragmatic guidelines were reviewed by a committee of the British Society of Gastroenterology and the Association of Coloproctology and published.10,11 The recommendations attempt to balance an individual’s genetic risk, using empiric data,10 against the risk of complications from the screening procedure of choice and to place individuals into a high, moderate, or low risk category. This risk is assigned by considering the age of onset and type of cancer in the patients’ relatives as well as the number and relationship of the affected relatives

Table 1.

Summary of referral and screening guidelines for colorectal cancer in Scotland

| Risk level | Criteria for referral and screening | Screening | Age to begin |

| Low risk |

|

|

|

| Moderate risk |

|

|

30–35 y and again at 55 y |

| High risk |

|

|

From 30 y of age or 5 y younger than the youngest affected For stomach cancer from 50 y of age or 5 y younger than the youngest stomach cancer |

The South East Scotland Genetic Service has seen a sixfold increase in CRC family history referrals over the last six years. Genetic counsellors are now conducting a CRC risk assessment service for these individuals, using national guidelines. We set out to determine the prevalence of significant neoplasia in people referred for colonoscopy, after stratification of risk on the basis of these empiric family history criteria, in order to inform screening strategy for those patients concerned about their family history.

METHODS

A two year cohort of asymptomatic individuals attending an appointment for CRC risk assessment, with a genetic counsellor, in the South East Scotland Genetic Service between January 2000 and December 2002 was studied. This included individuals concerned about their family history who had been referred directly for a colonoscopy and were re-routed for risk assessment prior to a decision regarding screening. General practitioners were notified of this. Individuals with or at risk from FAP were not included in these figures. Individuals who were symptomatic and were then referred by the Genetic Service for investigations were also not included.

Each individual had a detailed family history constructed and verified using cancer registry data, death certificates, or medical records. Risk and screening recommendations, based on this confirmed family history, were then discussed, as were genetic analysis and/or predictive testing, if applicable. The consultation also included discussion of possible environmental factors, warning signs, and the importance of healthy lifestyles. The colonoscopy procedure was discussed with those in the high and moderate risk groups. Those assessed at low risk were discharged but advised to inform the Genetic Service of any future changes in family history and to attend their general practitioner if they had any symptoms. Some individuals were assessed as “unclear” if the history did not fit easily into a moderate or high category but it was felt regular screening should be recommended.

Individuals with a family history fulfilling the Amsterdam criteria12 (high risk, table 1 ▶) were recommended to undergo colonoscopy every two years from the age of 30 years. Moderate risk cases were offered colonoscopy at the age of 35 years, or five years before the youngest age of diagnosis of CRC in the family if this resulted in colonoscopy at a younger age and, if this colonoscopy was normal, a second at the age of 55 years. Moderate risk is defined in table 1 ▶.

RESULTS

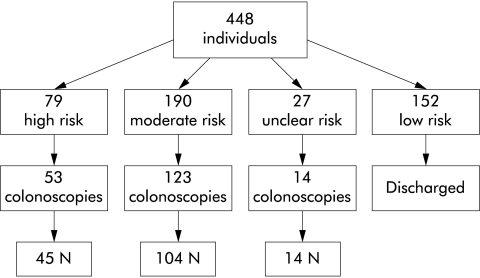

A total of 448 individuals attended the South East Scotland Genetic Service, which covers a population of approximately 1.5 million, for CRC risk assessment between January 2000 and December 2001 (fig 1 ▶). Colonoscopy findings, one examination per individual, were documented for asymptomatic individuals who had an increased risk. Rates of adenoma were detailed for the high and moderate risk groups. Fifty three individuals with a high risk family history and 123 individuals assessed at moderate risk were eligible for and had colonoscopic evaluation. Colonoscopy was complete to the caecum in 91.5% of individuals. In the remaining 15 patients, barium enema was performed after incomplete colonoscopy. The remainder of the 448 were individuals who were either not at increased risk, were too young for colonoscopy screening, had already had CRC, or did not want screening. Median age of individuals who underwent colonoscopy in both increased risk groups was 43 years (table 2 ▶). No incidence of CRC was detected and statistical analysis (Mann-Whitney test) indicated that there were no significant differences between the ages of the groups screened or the ages at which polyps or adenomas were detected in these groups.

Figure 1.

Study population.

Table 2.

Summary of the findings at prevalence colonoscopy screen

| High risk | Median age (y) | Moderate risk | Median age (y) | |

| Screened | 53 | 43 | 123 | 43 |

| Normal | 45 | 41 | 104 | 43 |

| Any polyp or adenoma | 8 | 49 | 19 | 45 |

| Adenoma | 4 (8%) | 5 (4%) | ||

| Metaplastic polyp | 4 (8%) | 14 (11%) |

Four individuals (8% (95% confidence limits (CL) 0.4–15%)) in the high risk group had adenomas (table 3 ▶). All of these individuals were less than 50 years of age, resulting in a 12% (95% CL 0.9–23%) occurrence of adenomas in the less than 50 year age group screened (34 individuals in total).

Table 3.

Colonoscopy results for high risk individuals

| Colonoscopy result | Location | Age (y) | Size |

| Tubulovillous adenoma | Rectosigmoid junction | 44 | 0.5 cm |

| Tubulovillous adenoma | Rectum | 48 | “Small” (unspecified) |

| Tubular adenoma | Rectum | 34 | “Small” (unspecified) |

| Tubular adenoma | Sigmoid | 48 | 1 cm |

In the moderate risk group, overall five individuals (4% (95% CL 0.6%–8%)) had an adenoma (table 4 ▶). Rate of adenoma occurrence in individuals less than 50 years was 2% (95% CL 0–5%) (87 individuals altogether) and 9% (95% CL 0–17%) in those over 50 years (36 individuals altogether). Using Fisher’s exact test, the proportion of patients less than 50 years found to have adenomas was significantly greater (p = 0.05) in the high risk group than in those at moderate risk.

Table 4.

Colonoscopy results for moderate risk individuals

| Colonoscopy finding | Location | Age (y) | Family history | Size |

| Tubular adenoma | Sigmoid | 38 | 3 affected relatives | “Small” (unspecified) |

| Tubulovillous adenoma | Rectum | 70 | 3 affected relatives | “Small” (unspecified) |

| 2 tubular adenomas | Sigmoid and caecum | 69 | 3 affected relatives | “Small” (unspecified) |

| Multiple (12) tubular adenoma | Throughout colon | 54 | 2 relatives affected with 1 under 55 y | Unspecified but largest 1 cm |

| Adenoma | Caecum | 36 | 2 relatives affected with 1 under 55 y | 1 mm |

Twenty metaplastic polyps were detected in 14 individuals (11% (95% CL 6–17%)) in the moderate risk group at a mean age of 44 years. Four of these individuals had two or more metaplastic polyps.

A total of 152 individuals who attended for CRC risk assessment were assessed as low risk. Thirty three had already had a normal colonoscopy result prior to attending for CRC risk assessment. Further colonoscopy was not recommended but one individual subsequently sought colonoscopy elsewhere, at which a single adenoma was removed. No further details are available but this family would now be reclassified as moderate risk.

DISCUSSION

In Scotland, CRC is a common illness and individuals have approximately a 1 in 20 lifetime risk of developing CRC.1 In the South East of Scotland, all referrals regarding risk and/or screening for CRC are routed to the Genetics Service. Risk assessment is conducted by genetic counsellors, with either nursing and/or scientific qualifications, using Scottish guidelines. Each consultand’s family history is verified and individual recommendations discussed at appointments which last approximately 45 minutes, prior to referral for colonoscopy if appropriate. This ensures that only individuals who are confirmed as at an increased familial risk are offered a colonoscopy. It also ensures that detailed discussion of the family history, risks, and patient concerns has occurred and individuals are more informed as to why they are being offered this invasive form of screening. Patients receive detailed summary letters which serve as a record of the consultation.

It is worth noting that after family history construction, about one third of individuals who were referred for CRC risk assessment did not meet increased risk criteria and were not eligible for a colonoscopy. It is the genetic counsellors’ experience that these individuals, who have been anxious enough to enquire about the family history, appreciate the information that is discussed with them and are often reassured by the consultation. Symptoms of CRC are always discussed and a patient information leaflet is given to reinforce this information. In addition, the fact that they have been diverted from the colonoscopy service eliminates possible medical complications of screening and hopefully reduces the number of asymptomatic individuals on the waiting list.

This two year study was undertaken to determine rates of cancer, adenomas, and polyps in asymptomatic individuals assessed at increased familial risk and referred for a single screening colonoscopy. All individuals will continue to be followed up with an ongoing audit of the service. Overall, no cases of CRC have been detected to date and no complications have arisen during the colonoscopy procedure.

We found that 8% of individuals who underwent colonoscopy in the high risk group and 4% in the moderate risk group had adenomas. Numbers were too small to detect if there was any significant difference overall. However, among individuals less than 50 years of age, the incidence of adenomas was six times greater in the high risk group (p = 0.05). It would be interesting to compare these findings with the rates of adenomas present in the Scottish population. Published studies from various populations appear to detail higher detection rates and tend to include older individuals. This may reflect the fact that these are often necropsy studies—for example, Williams and colleagues13 identified adenomas in 33% of subjects at a mean age of 66 years. More recently, a review of 906 asymptomatic individuals who underwent colonoscopy, at a mean age of 44.8 years, showed 10% of patients had tubular adenomas and 3.5% had an advanced neoplasm (>1 cm tubular adenoma, villous histology, or high grade dysplasia). No incidence of cancer was detected.14 In a UK trial examining the value of single flexible sigmoidoscopy at approximately 60 years of age, 12.1% of subjects had a distal adenoma. Of those then undergoing colonoscopy, 18.8% had a proximal adenoma and 0.4% a proximal cancer.15 Our figures suggest that patients in increased risk groups for developing CRC in Scotland have lower rates of adenomas than the general populations but our group were on average younger, with a median age of 43 years at screening. Adenoma prevalence however in our cohort was not substantially different from that in the general population at “low” risk.

Previous studies of asymptomatic individuals at an increased familial risk, similar to our moderate risk assessment, have indicated lower rates of adenomas in individuals having a colonoscopy at less than 50 years of age (4–15%) as opposed to those over 50 years of age (10–27%).5–7,16 Our moderate risk group also had fewer adenomas in the under 50 year age group, two individuals (2%) and three (9%) of those who underwent colonoscopy over the age of 50 years. These findings suggest that the majority of moderate risk asymptomatic individuals undergoing colonoscopy at less than 50 years of age, particularly aged 35 years, will have a normal examination. Our 8% adenoma rate in the high risk group is also considerably smaller than the 26.8% adenoma rate in HNPCC families published by Gaglia and colleagues.17 Again, it appears that in the Scottish population, those assessed as at increased risk have fewer adenomas than these other comparable populations. This could reflect the relatively small group size and/or the young median age of the study group (43 years). However, in previous studies of moderate risk, median ages were only slightly higher (44–47 years). Also, our study group all had a confirmed family history and at least one first degree relative affected with colorectal cancer. It was also a complete ascertainment of two years of patients attending the South East of Scotland Genetics Service for CRC risk assessment.

Lindgren at al showed that adenomas occurred at younger ages in individuals from HNPCC families than those whose family histories did not meet the Amsterdam criteria.18 They found that these individuals had their first adenoma at a mean age of 43 years. In our group, adenomas occurred at a younger age in the high risk group (46 years v 54 years in the moderate risk group). All adenomas detected in the high risk group occurred in individuals aged less than 50 years. No one over the age of 50 years, whose family history met Amsterdam criteria, had a neoplastic lesion.

Colorectal neoplasia is rare under the age of 50 years in the relatively large numbers classified as being at moderate risk, questioning the appropriateness of colonoscopy at age 35 years, or under the age of 50 years, which is the current recommendation for Scottish moderate risk subjects. Even patients who meet the Amsterdam criteria and are classified as at high risk have a low incidence of advanced adenomas before the age of 50 years, raising the possibility that screening intervals could possibly be lengthened. Further data however are required in order to create evidence based recommendations for these individuals.

Abbreviations

HNPCC, hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer

CRC, colorectal cancer

FAP, familial adenomatous polyposis

REFERENCES

- 1.ISD Scotland. Information on cancer incidence, mortality, survival and screening. www.show.scot.nhs.uk/isd/.

- 2.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1977–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarvinen HJ, Aarnio M, Mustonen H, et al. Controlled 15 year trial on screening for colorectal cancer in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2000;118:829–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarvinen HJ, Mecklin JP, Sistonen P. Screening reduces colorectal cancer rates in families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 1995;108:1405–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowling DJ, St John DJ B, MacRae F, et al. Yield from colonoscopic screening in people with a strong family history of common colorectal cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;15:939–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guillem JG, Forde KA, Treat MR, et al. Colonoscopic screening for neoplasms in asymptomatic first-degree relatives of colon cancer patients. Dis Colon Rectum 1992;35:523–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunt LM, Rooney PS, Hardcastle JD, et al. Endoscopic screening of relatives of patients with colorectal cancer. Gut 1998;42:71–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haites NE and Cancer Genetics Subgroup of the Scottish Cancer Group. Guidelines for regional genetic centres on the implementation of genetic services for breast, ovarian and colorectal cancer families in Scotland. CME J Gynaecol Oncol 2000;5:291–307. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scottish Cancer Group: Cancer Genetics Subgroup. Cancer genetics services in Scotland: guidance to support the implementation of genetics services for breast, ovarian and colorectal cancer predisposition Full reference document. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive Health Department, March2001.

- 10.Dunlop MG. Guidance on large bowel surveillance for people with two first degree relatives with colorectal cancer or one first degree relative diagnosed with colorectal cancer under 45 years. Gut 2002;51 (suppl 5) :V17–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunlop MG. Guidance on gastrointestinal surveillance for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, familial adenomatous polyposis, juvenile polyposis and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gut 2002;51 (suppl 5) :V21–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Collaborative Group on HNPCC. Dis Colon Rectum 1991;34:424–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams AR, Balasooriya BA, Day DW. Polyps and cancer of the large bowel: a necropsy study in Liverpool. Gut 1982;23:835–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imperiale TF, Wagner DR, Ching YL, et al. Results of screening colonoscopy among persons 40–49 years of age. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1781–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.UK Flexible Sigmoidoscopy Screening Trial Investigators. Single Flexible Sigmoidoscopy screening to prevent colorectal cancer: baseline findings of a UK multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2002;359:1291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Syrigos KN, Charalampopoulos A, Ho JL, et al. Colonoscopy in asymptomatic individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2002;9:439–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaglia P, Atkin WS, Whitelaw S, et al. Variables associated with the risk of colorectal adenomas in asymptomatic patients with a family history of colorectal cancer. Gut 1995;36:385–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindgren G, Liljegren A, Jaramillo E, et al. Adenoma prevalence and cancer risk in familial non-polypoposis colorectal cancer. Gut 2002;50:228–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]