Abstract

Background: The mechanisms behind microscopic colitis and exacerbations of ulcerative colitis are incompletely understood. It seems highly likely that both luminal antigens and bile are involved. The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that bile acids increase colonic mucosal permeability by activating enteric neurones.

Method: The effect of 4 mM deoxycholic acid (DCA) on the appearance rate of intravenously administered 3H-mannitol and 14C-urea into the lumen of the proximal and distal rat colon was measured in vivo and expressed as clearance. The nerve blocking agents atropine and hexamethonium were given intravenously, and lidocaine was applied onto the serosal surface of the colon, before and after DCA exposure

Results: DCA markedly increased clearance of the permeability probes into the lumen in both colonic segments and also the ratio of mannitol/urea clearance, particularly in the distal colon. Pretreatment with atropine, hexamethonium, and lidocaine significantly inhibited the increase in clearance by approximately 65–80% but did not affect the clearance ratio. In the distal colon, the inhibitory effect of lidocaine was not statistically significant. Also, administration of atropine and hexamethonium after DCA exposure significantly inhibited the DCA effect on clearance of the probes.

Conclusion: The results suggest that in vivo, the permeability increase induced by a moderate concentration of bile acid is to a large extent mediated by a neural mechanism involving muscarinic and nicotinic receptors. This mechanism may be a link between the central nervous system and colonic mucosal barrier function, and may be a new target for treatment.

Keywords: deoxycholic acid, enteric nervous system, colonic permeability, mannitol, urea

Bile acid malabsorption is a relatively common cause of diarrhoea of unknown origin in Western countries.1,2 In some patients, colonic biopsies are normal and in others, either a thickened subepithelial collagen layer or increased lymphocytic infiltration of the surface epithelium is seen.3 The mechanism through which moderately elevated concentrations of bile acids induce diarrhoea are largely unknown. In animal studies in vivo, moderate to high concentrations of deconjugated bile acids, particularly deoxycholic acid (DCA), damage the epithelium, reduce absorption and/or stimulate secretion, increase epithelial permeability, and enhance mucus secretion. The epithelial damage and thus the increased epithelial permeability has been attributed to the detergent properties of the bile acids.4 The lesions seem mainly to be localised to the colonic surface epithelium, implying a predominant effect on absorptive epithelial function.5–9 In vitro observations also indicate that activation of mucosal mast cells may be responsible for at least part of the tissue lesions.10,11

Studies from our laboratory have previously shown that in the small intestine the major part of the net fluid secretion elicited by DCA was induced via an intramural nervous reflex within the enteric nervous system (ENS).12 Other mechanisms—for example, inhibited absorption and passive leakage through the damaged part of the epithelium—probably also contribute. In the same segment, we also found that the marked increase in intestinal permeability induced by DCA was mainly neurally mediated; only a minor part was due to a direct effect of bile acids on epithelial cells.13

In general terms, the organisation of the ENS in the colon is similar to that in the small intestine, and studies in vitro also indicate similar function.14 However, in vivo, and in contrast with the findings in the small intestine, we recently found no evidence for involvement of the ENS in the weak antiabsorptive response elicited by 4 mM DCA in the rat colon.15 In contrast, in the same study, we observed that the reduction in transmucosal potential difference (PD) induced by DCA was attenuated by hexamethonium (nicotinic receptor antagonist), an effect that did not seem to be mediated by any change in electrogenic ion transport. This observation suggested to us that the decrease in PD in vivo may instead reflect a bile induced permeability increase, a response that might, in such cases, be mediated in part by a hexamethonium sensitive neural mechanism. The concept of neural modulation of colonic permeability is also in agreement with the observation that stress, via a cholinergic mechanism, elicits increased para- and transcellular transport of macromolecules both in the small intestine and colon.16

The aim of the present study was therefore to directly test the hypothesis that neural mechanisms contribute to the DCA induced increase in epithelial permeability in the rat colon. Colonic clearance of 3H-mannitol and 14C-urea was measured during exposure of the epithelium to 4 mM DCA, with or without administration of the nerve blocking agents atropine, hexamethonium, and lidocaine.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 240–450 g (Möllegard, Denmark) were used. Animals were kept under standardised environmental conditions (22°C, 60% humidity, artificial lightning 06.00 to 18.00 h) in the animal quarters for at least seven days prior to the experiments. The experiments were approved by the animal ethics committee at Göteborg University.

Operative procedures

The general setup and operative procedures have been described previously.17 Briefly, rats were fasted overnight with free access to water before the experiments. Anaesthesia was induced by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg body weight) and a cannula was placed in the trachea to ensure free airways. The right femoral vein was cannulated for administration of drugs. Systemic mean arterial pressure was continuously recorded by means of a pressure transducer (DPT-600 Single-Use Transducer; Peter von Berg Medizintechnik Gmbh, Eglharting, Germany) via a T tube connected to the femoral artery. The T tube was also used to maintain anaesthesia by continuous infusion of chloralose (3.6 mg/ml, 0.02 ml/min) given in a solution containing 69 mM glucose, 16.7 mM NaHCO3, and 58 mM NaCl to prevent dehydration and acidosis during and after surgery. Body temperature of the rat was maintained between 37and 38°C using radiant heat from overhead lamps and a heated dissection table.

After tracheotomy, an abdominal midline incision was performed and the colon was isolated with intact vascular and nervous supplies. Orally, the colon was divided at the border to the caecum and aborally, as far down towards the rectum as possible. The colon was divided into two segments of approximately equal size, just orally to the artery that supplies the distal segment. Colonic segments were then flushed with body warm normal saline. The kidneys were extirpated in order to keep plasma concentrations of permeability probes (see below) as constant as possible.

Measurement of net fluid transport

In separate experiments, the effect of atropine and DCA on net fluid transport (NFT) was measured using a volumetric method. At the beginning of each registration period, a known amount of Krebs solution (0.5–0.8 ml) was added to each segment and after one hour the segments were emptied with air. The volumes of the solutions added to and collected from the colonic segments were measured by administering the solution from preweighed syringes and sampling in preweighed tubes.

Measurement of colonic permeability

The two ends of the colonic segments were connected to a perfusion system of silicon tubings. The perfusion system to each of the segments was non-recirculating and contained a roller pump (Ismatec mini-micro 2/6, Zürich, Switzerland) and a reservoir with two compartments. The perfusate was a modified Krebs’ Henseleit solution containing (mM) NaCl 122, KCl, 3.5, NaHCO3 25, and KH2PO4 1.2, and was pumped (0.5 ml/min) from one of the compartments through the segment to the other compartment. During perfusion, segments were placed on the abdominal wall and covered with gauze and a thin plastic film.

The two probes 14C-urea (4 μCi, 70 nmol/l) and 3H-mannitol (20 μCi, 360 nmol/l) (NEN Life Science Products, Zaventem, Belgium) were given intravenously and allowed to equilibrate for one hour. Arterial plasma concentrations of the probes were determined three times during the experiment by measurement of 100 μl plasma samples in duplicate and a linear regression curve was calculated to estimate the plasma concentration at any time. Perfusate samples of 3 ml were obtained every 20 minutes from the perfusate after passage through the colon segment, and 9 ml of scintillation fluid (Ultima Gold XR, Packard, Campbell, USA) were added to each sample. The probes were counted in a Packard liquid scintillation analyser (1900 TR) to a standard deviation of 1%. Plasma clearance was expressed as μl(min/g) and was calculated from the appearance of the probes in the perfusate using the equation:

Clearance = (Cper×r)/(Cpl×g)

where C is the concentration (dpm/ml) of the perfusate (per) and of plasma (pl), r is the perfusion rate (μl/min), and g is the intestinal wet weight in grams (1 g colon tissue = 8.14 (0.27) and 10.56 (0.42) cm2 in the proximal and distal colon, respectively).

Experimental protocol

The same time protocol was followed in most experiments: after one hour of control recording, saline or drug was administered (intervention point), and after another hour, DCA (4 mM) was administered intraluminally. At the intervention point, saline, hexamethonium, atropine, or lidocaine was administered. Saline and atropine 1 ml/kg and 0.25 mg/kg, respectively, were given intravenously. Hexamethonium (10 mg/kg intravenously) was given every 45 minutes to compensate for biological clearance of the drug. Lidocaine was administered serosally by dropping it onto the serosal surface of the segment at a dose of 0.5 mg/10 cm every 10 minutes. In one experimental series, first atropine and then hexamethonium, given as above, were administered after the colon segments had been exposed to 4 mM DCA for one hour.

Drugs

The following drugs were used: atropine, hexamethonium, and DCA from Sigma Chemical Co (St Louis, Missouri, USA), and lidocaine from Astrazeneca Company (Sweden).

Statistics

All values are reported as mean (SEM) and statistical comparisons were made using Wilcoxon’s one sample (or matched pairs) test between different periods in the same group or the Mann-Whitney test (Wilcoxon’s two sample test) for different groups. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effects of DCA in the absence of nerve blockers

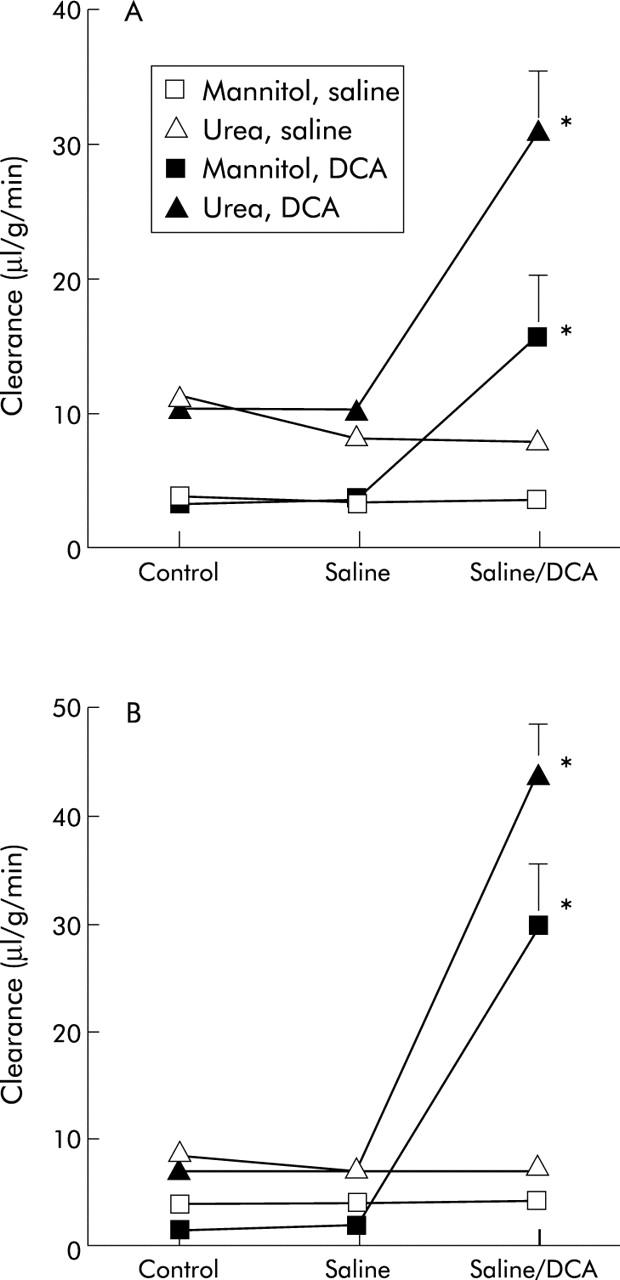

DCA markedly increased the colonic plasma clearance of mannitol and urea in both the proximal and distal segments (fig 1 ▶). DCA also increased the clearance ratio of mannitol/urea in both the proximal (from 0.35 (0.04) to 0.48 (0.05); p<0.05) and distal (from 0.26 (0.04) to 0.65 (0.05); p<0.05) colon, the value in the proximal colon being significantly less (p<0.05). In control experiments (no DCA administration), clearances of mannitol and urea as well as the clearance ratio of mannitol/urea in both the proximal and distal segments were constant during the experimental period (fig 1 ▶). Mean arterial blood pressure remained stable between 95 and 125 mm Hg during these experiments.

Figure 1.

Effect of deoxycholic acid (DCA) on the clearance of mannitol and urea from plasma into the intestinal lumen in the proximal (A) and distal (B) colon. Values are mean (SEM) (n = 7). *p<0.05 compared with the previous period.

Effects of nerve blockers before DCA

Hexamethonium rapidly reduced mean systemic blood pressure to 70–80 mm Hg but blood pressure then started to rise, eventually stabilising at approximately 80–90 mm Hg before the next dose was given. DCA, atropine, and lidocaine did not affect systemic pressure.

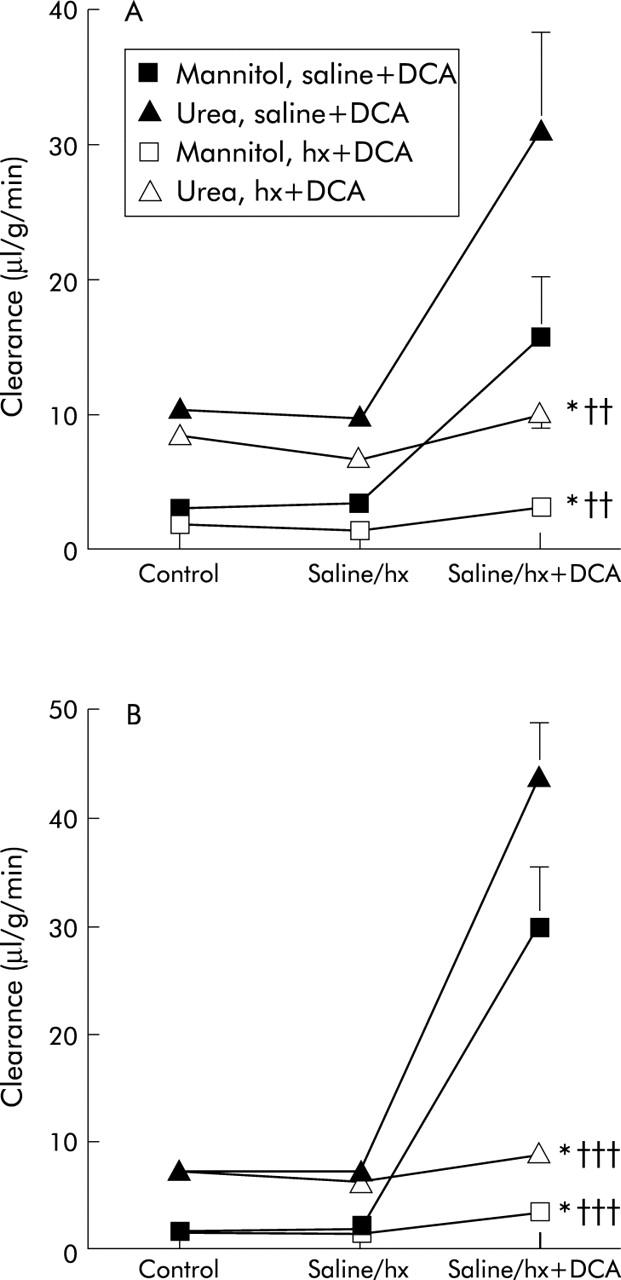

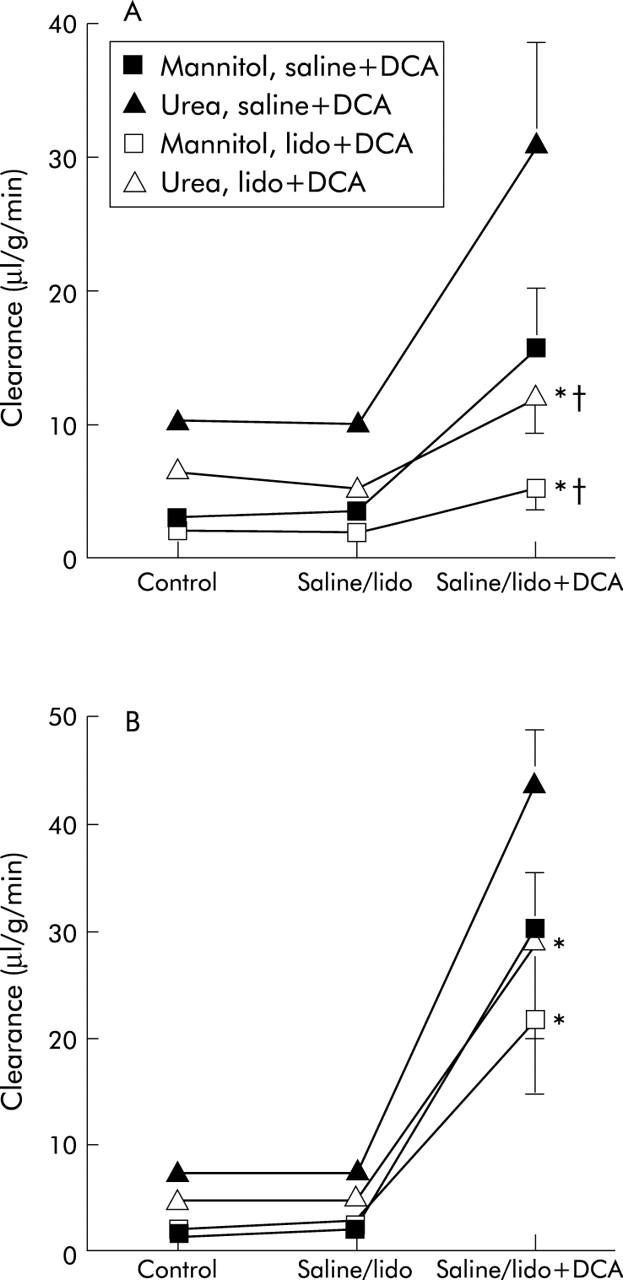

Clearance of mannitol and urea as well as the ratio of mannitol/urea were slightly but significantly decreased by hexamethonium in the proximal colon while corresponding values in the distal colon were only close to statistical significance. In contrast, atropine and lidocaine had no significant effects on clearance of mannitol and urea in either the proximal or distal segments (figs 2 ▶–4 ▶).

Figure 2.

Effect of pretreatment with hexamethonium (hx) (intravenously) on the deoxycholic acid (DCA) effect on clearance of mannitol and urea in the proximal (A) and distal (B) colon. Values for the effect on clearance of DCA from fig 1 ▶ are included. Values are mean (SEM), n = 7. *p<0.05 compared with the previous period; ††p<0.01, †††p<0.001 compared with saline+DCA values.

Figure 4.

Effect of serosal lidocaine (lido) on the deoxycholic acid (DCA) effect on clearance of mannitol and urea in the proximal (A) and distal (B) colon. Values for the effect on clearance of DCA from fig 1 ▶ are included. Values are mean (SEM), n = 7. *p<0.05 compared with the previous period; †p<0.05 compared with saline+DCA values.

Effects of DCA after nerve blockade

DCA administered after atropine, hexamethonium, and lidocaine still caused a significantly increase in clearance of mannitol and urea in both the proximal and distal segments. However, the increase in clearance was significantly smaller compared with the effect of DCA per se—that is, reduced to approximately 20% and 33% of mannitol and urea in the proximal and 11% and 20% of mannitol and urea in the distal colon in the hexamethonium group, 36% of mannitol and urea in the proximal and 36% and 34% of mannitol and urea in the distal colon in the atropine group (figs 2 ▶, 3 ▶). DCA also increased the clearance ratio mannitol/urea in the hexamethonium group (to 0.33 (0.4) and 0.40 (0.04) in the proximal and distal colon, respectively) as well as in the atropine group (to 0.46 (0.03) and 0.75 (0.07) in the proximal and distal segments, respectively)—that is, values close to those obtained with DCA alone.

Figure 3.

Effect of pretreatment with atropine (atr) (intravenously) on the deoxycholic acid (DCA) effect on clearance of mannitol and urea in the proximal (A) and distal (B) colon. Values for the effect on clearance of DCA from fig 1 ▶ are included. Values are mean (SEM), n = 7. *p<0.05 compared with the previous period; †p<0.05 compared with saline+DCA values.

Lidocaine also significantly inhibited the DCA induced increase in clearance of mannitol and urea in the proximal colon (fig 4 ▶). The effect of lidocaine was not statistically significant in the distal colon. The ratio of mannitol/urea reached values close to those obtained with DCA alone (0.38 (0.04) and 0.75 (0.07) for the proximal and distal colon, respectively). After lidocaine, DCA induced a larger increase in the clearance of mannitol and urea in the distal than in the proximal segment (p<0.05).

Pooling the clearance ratio values for the proximal and distal colon after DCA plus nerve blockers gave ratios of 0.39 (0.02) and 0.62 (0.05) in the proximal and distal colon, respectively (p<0.01). However, there was no significant difference compared with the effect of DCA alone in the respective colon segments.

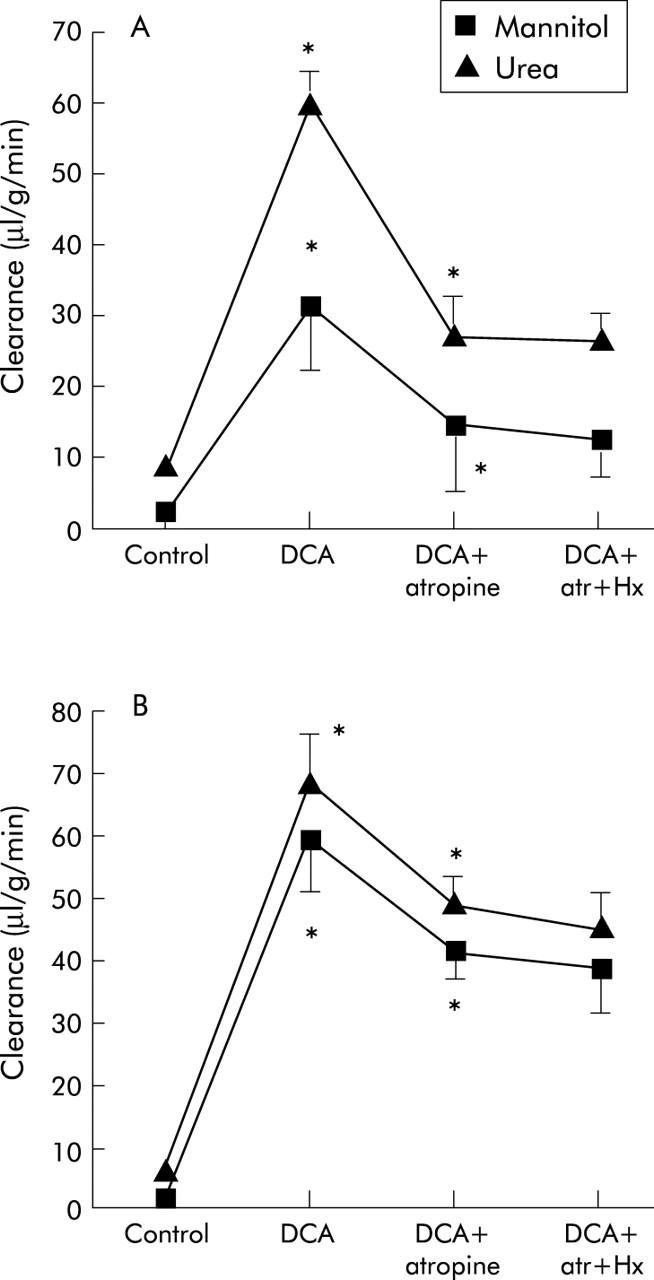

Effects of nerve blockers after bile acid

In one series of experiments, the nerve blockers were given after DCA. The results showed that atropine in this situation significantly decreased clearance of mannitol and urea in both the proximal and distal colon (fig 5 ▶). Compared with the effect of DCA per se, the clearance values were reduced to approximately 45% of mannitol and urea clearance in the proximal and 69% and 71% of mannitol and urea clearance in the distal colon, respectively. Hexamethonium, given after atropine, had no further effects on clearance in either segment (fig 5 ▶). The clearance ratio of mannitol/urea was not affected by the two nerve blockers. Compared with the effect of atropine plus DCA (fig 3 ▶), clearance of mannitol and urea in the distal segment was significantly increased (p<0.05).

Figure 5.

Effects of atropine (atr) and hexamethonium (hx) on deoxycholic acid (DCA) induced changes in the clearance of mannitol and urea in the proximal (A) and distal (B) colon. Values are mean (SEM), n = 7. *p<0.05 compared with the previous period.

Net fluid transport

In a previous study,15 we showed that DCA slightly reduced net fluid absorption in the proximal colon but had no significant effect on NFT in the distal colon (table 1 ▶). Furthermore, hexamethonium per se increased net absorption in the proximal colon and turned net fluid secretion into net fluid absorption in the distal colon. Pretreatment with hexamethonium did not change the DCA effect on NFT (table 1 ▶). In the present study, atropine per se did not change NFT in the proximal or in the distal colon (proximal colon: control +72 (8); atropine +74 (7); distal colon: control −20 (5); atropine −13 (5) μl/(min/100 cm2); negative values indicate secretion). During atropine blockade (table 1 ▶), DCA in the proximal colon significantly reduced fluid absorption from 74 (7) to 41 (9) μl/(min/100 cm2). NFT in the distal colon was unaffected (atropine −13 (5), atropine+DCA −13 (9) μl/(min/100 cm2). Using the fluid values from the two studies we found no significant relationship between clearances of mannitol and urea and NFT. This was the case for both the proximal and distal segments in the control, DCA, atropine, and hexamethonium groups.

Table 1.

Changes in net fluid transport (ΔNFT) induced by 4 mM deoxycholic acid (DCA) in the proximal and distal colon after pretreatment of animals with saline (control), atropine, or hexamethonium (Hx)

| ΔNFT | |||

| Control+DCA | Atropine+DCA | Hx+DCA | |

| Proximal colon | −50 (17) (8)* | −33 (9) (6)* | −35 (17) (6)* |

| Distal colon | −45 (27) (8) | 3 (8) (6) | −36 (21) (6) |

NFT is expressed in μl/(min/100 cm2).

n values are given in parentheses. *p<0.05.

A minus sign indicates net fluid secretion.

The control and hexamethonium values are taken from Sun and colleagues.15

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study showed that DCA markedly increased the plasma clearance of mannitol and urea, and their clearance ratio, in both the proximal and distal colon, implying a marked increase in epithelial permeability. Similar results have been reported in other in vivo studies.6,8,18–22 Simultaneously, DCA also induced moderate morphological changes. Our own observations17 as well as those of others5–7,22,23 showed that the lesions induced by DCA in concentrations of 3–5 mM are confined to the surface epithelium, without causing disruption of the epithelial lining. This indicates that the increased permeability is primarily localised to the paracellular pathway and tight junctions. The same conclusion has also been made from in vitro observations24,25 and is supported by the observed reversibility of the effects.7,21

DCA increased the clearance ratio of mannitol/urea to 0.48 (0.05) and 0.65 (0.05) in proximal and distal colon. These changes in ratios cannot be due to changes in mucosal capillary blood flow as the transport of the probes into the lumen are restricted by the epithelial tight junctions and not by the pores in the capillary membrane. The theoretical ratio of the diffusion constants of the two probes in free water is 0.55–0.60. Clearance values in the presence of DCA in the present study were found to be of a similar order of magnitude in the distal colon and somewhat less in the proximal part of the colon. This indicates that the paracellular pathway allows free diffusion in the distal colon and a somewhat restricted diffusion in the proximal segment. Taken together, these observations indicate that the permeability of the tight junctions corresponds to cylindrical pores with a radius of 35–50 Å and 25–35 Å in the distal and proximal colon, respectively.26 The value in the distal colon is similar to values seen in the small intestine.13

In a previous study,15 we found that 4 mM DCA had no consistent effect on NFT (proximal and distal colon), and that nerve blockers did not change this pattern. This is in sharp contrast to the situation in the small intestine where DCA induces a hexamethonium sensitive increase in fluid secretion.12 Thus the main mechanism behind the DCA effect on fluid transport in the small intestine, activation of a nervous reflex, does not seem to be present in the colon mucosa. Furthermore, clearance ratios during DCA exposure, as discussed above, were near or below the ratio for free diffusion of water which indicates that solvent drag was of minor importance for the effect of DCA. This conclusion is also supported by the observed lack of correlation between NFT and clearance of the probes. The main effect of this concentration of DCA on fluid transport in vivo may therefore to be inhibition of absorption due to a direct effect on the surface epithelium.21,15

Taken together with previous work, our in vivo results show that 4 mM DCA, a concentration that can be found in some pathophysiological situations in the human colon,27 inhibits active absorption and increases colonic motility and mucus secretion18,28 but does not stimulate active fluid secretion.15 Thus the prominent flushing and diluting mechanism seen in the small intestine does not seem to be present in the colon.

Pretreatment of animals with atropine and hexamethonium before administration of DCA markedly inhibited clearance of the two probes in both the proximal and distal colon. Inhibition was of the same order of magnitude in both colonic segments. Theoretically, this effect could be explained by a decrease in solvent drag of the probes through the epithelium due to inhibited fluid secretion. However, neither atropine nor hexamethonium affected DCA induced NFT, as discussed above.15 This strongly indicates that a large part of the increased clearance values of the permeability probes were due to enhanced epithelial permeability elicited by a nervous reflex containing both nicotinic and muscarinic receptors. Furthermore, as hexamethonium per se only induced a small decrease in clearance of the two probes and neither atropine nor lidocaine alone had any effect on clearance, there is no evidence for any nervous “tone” regulating basic epithelial permeability in the rat colon, at least not under our experimental conditions. Moreover, the clearance ratios were not affected by the nerve blockers which suggests that the nerve mechanism changes the number but not the size of the pores in the epithelium. A similar observation has been made in the small intestine but with the difference that atropine was not inhibiting the DCA effect.13

As concluded above, there is strong evidence to suggest that the increased permeability is caused by changes in tight junctions. Furthermore, the blood to lumen technique used in this study in the control situation in principal only reflects the permeability of the crypt epithelium.29 This strongly suggests that the main increase in permeability due to luminal DCA is at the surface epithelium—that is, where the epithelial lesions are located and where no secretory processes are localised. However, as increased permeability seems to be due to both a direct effect of DCA and a nervous mechanism, location of the enhanced permeability to the crypt region is possible.

Applying lidocaine onto the serosal surface of the small intestine only anaesthetises the outer myenteric plexus of the ENS and the external innervation.30 In rat colon, the longitudinal muscle layer has a similar thickness (Jodal, unpublished observation)—that is, serosally applied lidocaine can be expected to mainly affect the myenteric plexus also in the colon. Accordingly, lidocaine also inhibited the DCA induced increase in clearance of both probes in the proximal segment to the same extent as hexamethonium and atropine while the effect in the distal colon was not significant. We therefore propose that the nerve reflex inducing the increased permeability may be differently organised in the two parts of the colon. In the proximal colon, the myenteric plexus plays a crucial role whereas in the distal colon an intact submucosal plexus seems to suffice for the permeability increasing neural mechanism to operate.

Finally, a brief comment on the potential clinical relevance of our key finding: that is, that the colonic permeability response to luminal agents, particularly in the distal colon, may be neurally regulated. Both microscopic colitis and ulcerative colitis have a highly unpredictable clinical course. In microscopic colitis, the disease may for example resolve for unknown reasons, and in ulcerative colitis we do not know what triggers exacerbations. Patients with ulcerative colitis also have a markedly increased mucosal permeability to for example, 51Cr-EDTA.31,32 If the mechanism described in the present study also exists in humans, it may well contribute to the variable clinical course of inflammatory bowel disease, including an impact on central nervous effects. If this mechanism increases permeability sufficiently to influence antigen load, it might be a potential target for anti-inflammatory therapy. Interestingly, luminal lidocaine has been reported to have a beneficial effect in distal ulcerative colitis,33 an effect that may be induced via a nervous influence on epithelial permeability. Thus our data encourage the search for mechanisms in humans.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council (Nos 2855 and 8288), the Faculty of Medicine, Göteborg’s University, and by the Åke Wiberg Foundation.

Abbreviations

DCA, deoxycholic acid

ENS, enteric nervous system

NFT, net fluid transport

PD, potential difference

REFERENCES

- 1.Hofmann AF. The syndrome of ileal disease and the broken enterohepatic circulation: choleretic enteropathy. Gastroenterology 1967;52:752–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sciaretta G, Morrone B, Malaguti P. Absence of histopathological changes of ileal and colon functional chronic diarrhea associated with bile acid malabsorption, assessed by SeHCAT test: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:1058–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ung KA, Gillberg R, Kilander A, et al. Role of bile acids and bile acid binding agents in patients with collagenous colitis. Gut 2000;46:170–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binder HJ, Sandle GI. Electrolyte transport in the mammalian colon. In: Johnson LR, ed. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. New York: Raven Press, 1994:2133–72.

- 5.Saunders DR, Hedges JRSJ, Esthers L, et al. Morphology and functional effects of bile salts on rat colon. Gastroenterology 1975;68:1236–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chadwick VS, Gaginella TS, Carlson GL, et al. Effect of molecular structure on bile acid-induced alterations in absorption, permeability, and morphology in the perfused rabbit colon. J Lab Clin Med 1979;94:661–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goerg KJ, Gross M, Nell G, et al. Comparative study of the effect of cholera toxin and sodium deoxycholate on the paracellular permeability and net fluid and electrolyte transport in the rat colon. Naunyn Schmiedeburgs Arch Pharmacol 1980;312:91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vahouny GV, Satchithanandam S, Lightfoot F, et al. Morphological disruption of colonic mucosa by free cholestyramine-bound bile acids. Dig Dis Sci 1984;29:432–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Argenzio RA, Henrikson CK, Liacos JA. Effect of prostaglandin inhibitors on bile salt-induced mucosal damage of porcine colon. Gastroenterology 1989;96:95–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quist RG, Ton-Nu H, Lillienau J, et al. Activation of mast cells by bile acids. Gastroenterology 1991;101:446–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelbmann CM, Schteingart CD, Thompson SM, et al. Mast cells and histamine contribute to bile acid-stimulated secretion in the mouse colon. J Clin Invest 1995;95:2831–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karlström L. Mechanisms in bile salt-induced secretion in the small intestine. Acta Physiol Scand 1986;126(suppl 549):1–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fihn B-M, Sjöqvist A, Jodal M. Involvement of enteric nervous system in permeability changes due to deoxycholic acid in rat jejunum in vivo. Acta Physiol Scand 2003;178:241–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooke HJ, Reddix RA. Neural regulation of intestinal electrolyte transport. In: Johnson LR, ed. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. New York: Raven Press, 1994:2083–132.

- 15.Sun Y, Fihn B-M, Jodal M, et al. Effects of nicotinic receptor blockade on colonic mucosal response to luminal bile acids in anaesthetized rats. Acta Physiol Scand 2003;178:251–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Söderholm JD, Perdue MH. Stress and the gastrointestinal tract II. Stress and the intestinal barrier. Am J Physiol 2001;280:G7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun Y, Fihn B-M, Jodal M, et al. Effect of blocking agents on motor activity and secretion in the proximal and distal colon: Evidence of marked segmental differences in nicotinic receptor. Scand J Gastroenterol 2000;35:380–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binder HJ, Dobbins JW, Racusen LC, et al. Effect of propranolol on ricinoleic acid- and deoxycholic acid-induced changes of intestinal electrolyte movement and mucosal permeability. Gastroenterology 1978;75:668–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farack UM, Nell G, Lueg O, et al. Independence of the activation of mucus and potassium secretion on the inhibition of sodium and water absorption by deoxycholate in rat colon. Naunyn Schmiedeburgs Arch Pharmacol 1982;321:336–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farack UM, Nell G, Loeschke K, et al. Is the secretagogue effect of deoxycholic acid mediated by adenylate cyclase-cAMP system. Digestion 1983;28:170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Argenzio RA, Whipp SC. Comparison of the effect of disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate, theophylline, and deoxycholic acid on colonic ion transport and permeability. Am J Vet Res 1983;44:1480–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henrikson CK, Argenzio RA, Liacos JA, et al. Morphology and functional effects of bile salt on the porcine colon during injury and repair. Lab Invest 1989;60:72–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breuer NF, Rampton DS, Tammar A, et al. Effect of colonic perfusion with sulfated and nonsylfated bile acids on mucosal structure and function in the rat. Gastroenterology 1983;84:969–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freel RW, Hatch M, Earnest DL, et al. Role of tight-junctional pathways in bile salt-induced increases in colonic permeability. Am J Physiol 1983;245:G816–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dharmsathaphorn K, Huott PA, Vongkovit P, et al. Cl− secretion induced by bile salts. A study of the mechanism of action based on a cultured colonic epithelial cell line. J Clin Invest 1989;84:945–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sjöqvist A, Fihn B-M. Transcellular fluid secretion induced by cholera toxin and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in the small intestine of the rat. Acta Physiol Scand 1993;148:393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cummings JH, James WPT, Wiggins HS. Role of the colon in ileal resection diarrhea. Lancet 1973;1:344–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirwan WO, Smith AN, Mitchell WD, et al. Bile acids and colonic motility in the rabbit and human. Gut 1975;16:894–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fihn B-H, Jodal M. Permeability of the proximal and distal rat colon crypt and surface epithelium to hydrophilic molecules. Plügers Arch 2001;441:656–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cassuto J, Siewert A, Jodal M, et al. The involvement of intramural nerves in cholera toxin induced intestinal secretion. Acta Physiol Scand 1983;117:195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenkins RT, Jones DB, Goodacre RL, et al. Reversibility of increased intestinal permeability to 51Cr-EDTA in patients with gastrointestinal inflammatory diseases. Am J Gastroenterol 1987;82:1159–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jenkins RT, Ramage JR, Jones DB, et al. Small bowel and colonic permeability to 51Cr-EDTA in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Invest Med 1988;11:151–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Björk S, Dahlström A, Ahlman H. Treatment of distal colitis with local anaesthetic agents. Pharmacol Toxicol 2002;90:173–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]