Abstract

Background and aims: The mechanisms underlying intestinal secretion in rotavirus diarrhoea remain to be established. We previously reported that rotavirus evokes intestinal fluid and electrolyte secretion by activation of the enteric nervous system. We now report that antagonists for the 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 receptor (5-HT3) and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) receptor, but not antagonists for 5-hydroxytryptamine 4 receptor or the muscarinic receptor, attenuate rotavirus induced diarrhoea.

Methods: Neurotransmitter antagonists were administered to wild-type or neurokinin 1 receptor knockout mice infected with homologous (EDIM) or heterologous (RRV) rotavirus.

Results: While RRV infected mice had diarrhoea for 3.3 (0.2) days (95% confidence interval (CI) 3.04–3.56), the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist (granisetron) and the VIP receptor antagonist (4Cl-D-Phe6,Leu17)-VIP both reduced the total number of days of RRV induced diarrhoea to 2.1 (0.3) (95% CI 1.31–2.9) (p<0.01). EDIM infected mice treated with granisetron had a significantly shorter duration of diarrhoea (5.6 (0.4) days) compared with untreated mice (8.0 (0.4) days; p<0.01). Experiments with neurokinin 1 receptor antagonists suggest that this receptor may possibly be involved in the secretory response to rotavirus. On the other hand, rotavirus diarrhoea was not attenuated in the neurokinin 1 receptor knockout mice.

Conclusions: Our results suggest that the neurotransmitters serotonin and VIP are involved in rotavirus diarrhoea; observations that could imply new principles for treatment of this disease with significant global impact.

Keywords: rotavirus, enteric nervous system, diarrhoea, vasoactive intestinal peptide, serotonin

Rotavirus is the major cause of infantile gastroenteritis worldwide and the infection is associated with approximately 600 000 deaths every year, predominantly in developing countries.1

Rotavirus infects mature enterocytes in the mid and upper villus which leads to cell death and villus atrophy. However, the magnitude of the pathological changes appears to be variable, and it is uncertain whether a direct link exists between tissue damage and diarrhoea.2 The magnitude of rotavirus evoked fluid secretion cannot be explained solely by decreased fluid and electrolyte absorption. Instead, it is most likely that secretory mechanisms are involved.3 Moreover, the clinical picture of the disease includes vomiting and nausea, symptoms that indicate nerve activation. These considerations give rise to questions concerning mechanisms for diarrhoea other than tissue damage.

During the past decades it has become increasingly apparent that intestinal secretion induced by bacterial pathogens is partially due to activation of enteric secretomotor neurones.4–6 The guinea pig is the reference animal in the enteric nervous system (ENS) field but it is clear that in other animals there is also a strong link between ENS and ion and water transport.7,8 An outline of the properties of the intramural secretory neural mechanism for non-invasive pathogens comprises at least three parts: (1) observations support the view that the communicator cells between the lumen and nervous system may be enterochromaffin cells releasing serotonin (5-HT) and/or substance P (SP)5,6; (2) activated primary afferent neurones release neurotransmitters at synapses in the submucous and/or myenteric plexus4,5,9; and (3) secretomotor neurones activating secretory crypt cells are suggested to act through cholinergic muscarinic (M3) receptors or the vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) receptor.10

We recently reported that rotavirus may also evoke intestinal fluid and electrolyte secretion by activation of the ENS.11 Different drugs blocking nerve activity (tetrodotoxin, lidocaine, mecamylamine, and hexamethonium) were used to attenuate rotavirus induced fluid and electrolyte secretion in vitro and to attenuate diarrhoea in vivo.

In the present experiments, we studied the mechanism behind enteric neurone activation and rotavirus induced fluid secretion. Despite extensive experimental evidence for the involvement of neurogenic secretion in several intestinal secretion models, it has not previously been shown that blockade of specific enteric neurone activity has any beneficial effect on acute diarrhoea in the clinical setting. The aim of this study was to identify specific neurotransmitters involved in rotavirus diarrhoea in the clinical setting.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animals

Rotavirus naive Balb/c mice (B&K Laboratories, Sollentuna, Sweden) were mated at eight weeks of age. Genetically engineered Balb/c mice deficient in the neurokinin 1 receptor (NK-1R−/−) were kindly provided by Dr Norma P Gerard (Boston, Massachusetts, USA).12 Mice were housed in standard cages with free access to food and water. Pregnant mice were transferred to separate cages one week before the expected day of birth. The day of birth was noted as day 1. The number of offspring was adjusted to 5–8 in each litter for standardisation of conditions, and litters were weighed before administration of drugs. Litters were not separated from their mothers during the experimental period. The experimental protocol was approved by the animal ethics committee in Stockholm (registration No N38/01).

Rotavirus infection

Two different rotavirus strains were given: rhesus rotavirus (RRV) and wild-type murine (EDIM) rotavirus. Although RRV provides a well characterised standard rotavirus infection model in mice,13–15 the virus is heterologous and was thus complemented by experiments with the homologous strain EDIM.16 RRV was grown and harvested from MA104 cells and viral titres determined as previously described.14 Wild-type murine (EDIM) rotavirus was kindly provided by Marie Rippenhoff-Talty (Buffalo, USA). Five day old mice were orally inoculated with either 6×106 PFU of RRV (10 DD50, diarrhoea doses), a dose that causes diarrhoea in >90% of inoculated animals, or 500 DD50 of EDIM. The highest dilution that caused diarrhoea in 50% of mice was defined as DD50.

Definition and quantification of diarrhoea

Mice were examined once a day for signs of diarrhoea, as defined by liquid yellow stools induced by gentle abdominal palpation.14 The presence or absence of diarrhoea in each animal was also judged by an independent observer. Individual mice were followed every day after inoculation and the total number of days with diarrhoea (NDD) was noted. The daily percentage of mice with diarrhoea was calculated by dividing the number of mice with positive stool samples by the total number of mice in the group.

Receptor blockade experiments

Isotonic saline was administered twice a day for two days to non-infected mice to serve as a control. All drugs were administered intraperitoneally.

VIP receptor antagonist

The VIP receptor antagonist (4Cl-D-Phe6,Leu17)-VIP (0.1, 0.5, 1.5 mg/kg) or a combination of the VIP receptor antagonist (0.5 mg/kg) and the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist (granisetron 2 mg/kg) was given at 0, 8, 18, 29, 41, and 48 hours post inoculation.

Muscarinic receptor antagonist

The muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine (3 and 10 mg/kg) was administered at 0, 8, 24, 32, and 48 hours post inoculation.

Serotonin receptor antagonists

The 5-HT3 receptor antagonist (granisetron), having a known long half life17, was administered at 0, 24, and 48 hours post inoculation at a dose of 0.1, 0.5, 2, 5, and 8 mg/kg to RRV infected mice. Granisetron was given to EDIM infected mice for six days from the time of infection. The 5-HT4 receptor antagonist RS 39604 (1 and 5 mg/kg) was given at 0, 8, 24, 32, and 48 hours post inoculation

Tachykinin receptor antagonists

RRV or cholera toxin (CT) (3 mg/kg orally) was administered to Balb/c mice and NK-1R−/− Balb/c mice at five days of age.

The SP receptor antagonist (D-Pro2, D-Trp7, 9)-SP (1, 5, and 10 mg/kg), the NK-1 receptor antagonists Sendide (Tyr6, D-Phe7, D-His9)-SP6–11 and CP-96,345 (1, 5, and 10 mg/kg), and the inactive enantiomer CP-96,344 (5 mg/kg) were given at 0, 8, 24, 32, and 48 hours post inoculation

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue preparation for immunohistochemistry has been described elsewhere.18 Slides with transversally cut ileal cryopreparations from wild-type and NK-1R−/− Balb/c mice were prepared. Slides were preincubated in normal goat serum (1:10) (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co, St Louis, Missouri, USA) before incubation with the primary NK-1 receptor rabbit antibody (1:250), followed by a secondary antibody, fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated goat antirabbit IgG (1/100). Slides were mounted in carbonate buffered glycerol (1:1, pH 8.5) and the immunoreaction was viewed with a Leitz epifluorescence microscope. The NK-1 receptor antibody (#94168) was kindly donated by Dr NW Bunnett (University of California, San Francisco, California, USA).

Drugs

The VIP receptor antagonist (4Cl-D-Phe6,Leu17)-VIP and atropine were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. The SP receptor antagonist (D-Pro2, D-Trp7, 9)-SP and the NK-1 receptor antagonist Sendide (Tyr6, D-Phe7, D-His9)-SP6–11 were provided by Bachem AG (Switzerland). CP-96,345 and its inactive enantiomer CP-96,344 were obtained from Pfizer Diagnostics. Granisetron was supplied by SmithKline Beecham (UK). The 5-HT4 receptor antagonist RS 39604 was obtained from Tocris Cookson (UK). CT was obtained from List Biological Lab (Campbell, California, USA). Fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated goat-rabbit IgG was obtained from Jackson-Immunoresearch (West Grove, Pennsylvania, USA). All drugs given to mice were dissolved in isotonic saline.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean (SEM). Statistical analyses of all data were performed using the Student’s t test and calculation of 95% confidence interval (CI). Univariate analysis of variance was used for correlation between numbers of litters and number of days with diarrhoea. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Control mice

Forty two RRV infected saline-treated mice were used. RRV infected mice had diarrhoea for 3.3 (0.2) days (95% CI 3.04–3.56). These mock treated mice were compared with drug treated mice. Isotonic saline was given as a control and did not induce diarrhoea.

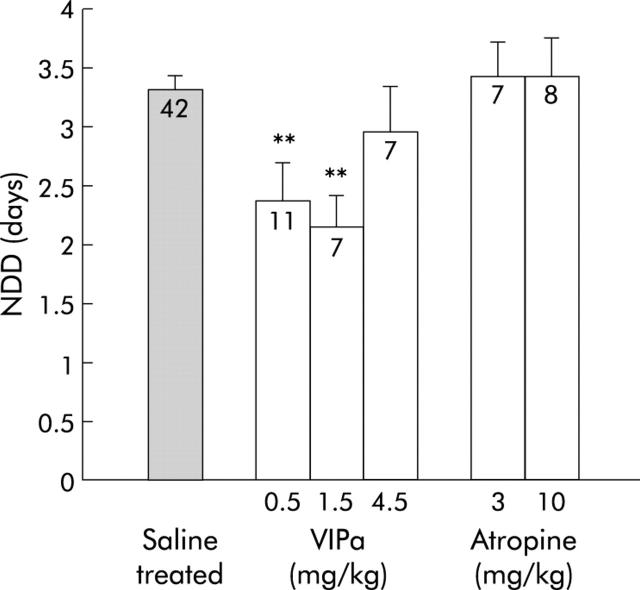

Vasoactive intestinal peptide is involved in rotavirus diarrhoea

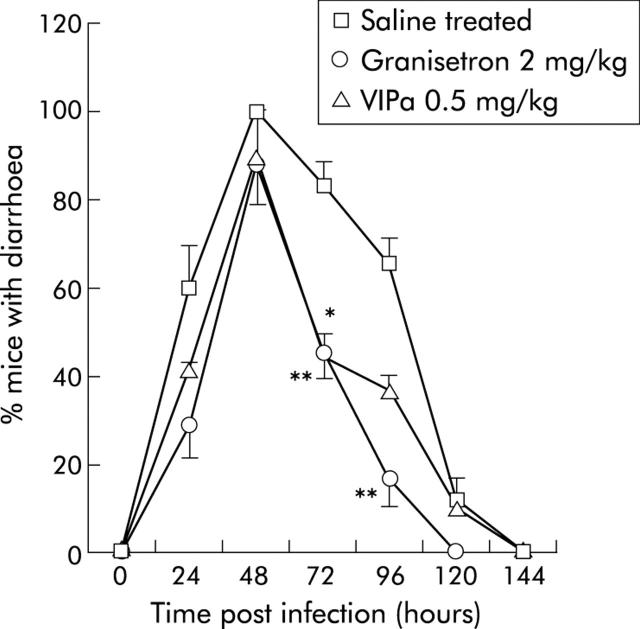

The VIP receptor antagonist (4Cl-D-Phe6, Leu17)-VIP was used to attenuate the effects of VIPergic secretomotor neurones and thus provide information on the role of VIP in rotavirus diarrhoea. The antagonist decreased NDD (fig 1 ▶) from 3.3 (0.2) days (95% CI 3.04–3.56) in saline treated RRV infected mice to 2.4 (0.3) days (95% CI 1.61–3.11) (0.5 mg/kg) and 2.1 (0.3) days (95% CI 1.31–2.9) (1.5 mg/kg) in treated mice. There was no statistically significant effect with 4.5 mg/kg. In the VIP receptor antagonist treated group (0.5 and 1.5 mg/kg), 42% and 14%, respectively, had diarrhoea at 24 h post inoculation compared with 62% for control mice (fig 2 ▶). Furthermore, fig 2 ▶ also shows that fewer mice had diarrhoea at 72–96 hours post inoculation after VIP receptor antagonist treatment compared with mock treated mice.

Figure 1.

Number of days with diarrhoea (NDD) after treatment with a vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor antagonist (VIPa) (0.5, 1.5, and 4.5 mg/kg) and atropine (3, 10 mg/kg). Non-treated RRV infected mice served as controls. Numbers in columns indicate number of mice. Values are means (SEM). **p<0.01 compared with controls (Student’s t test).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of mice with diarrhoea after rotavirus infection (RRV) plotted versus hours post inoculation. Saline treated RRV infected mice (number of litter = 8) were compared with mice treated with granisetron (2 mg/kg; number of litter = 4) or vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor antagonist (VIPa) (0.5 mg/kg; number of litter = 2). Values are means (SEM). *p<0.05, **p<0.01 compared with controls (Student’s t test).

Effect of the muscarinic receptor antagonist

In addition to VIPergic secretomotorneurones, there is also a population of cholinergic atropine sensitive enteric secretomotor neurones. The muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine was used to examine involvement of these neurones in rotavirus evoked diarrhoea. Atropine (3 and 10 mg/kg) given to RRV infected mice did not modify diarrhoea (fig 1 ▶).

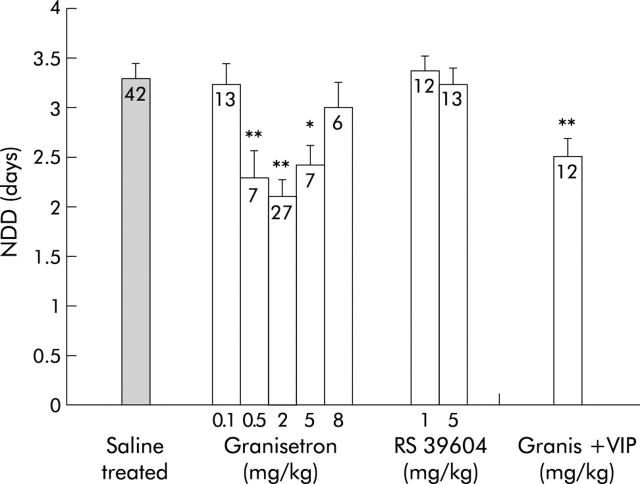

Serotonin is involved in rotavirus diarrhoea

5-HT released from enterochromaffin cells or from enteric interneurones may activate the enteric secretory reflex via 5-HT3 and/or 5-HT4 receptors. Given these observations, 5-HT3 receptor and 5-HT4 receptor antagonists were examined for their effect on rotavirus diarrhoea. As shown in fig 3 ▶, granisetron (0.5, 2, and 5 mg/kg) significantly decreased NDD to 2.3 (0.3) days (95% CI 1.58–2.98) (p<0.01), 2.1 (0.3) days (95% CI 1.79–2.43) (p<0.01), and 2.4 (0.2) days (95% CI 1.93–2.92) (p<0.05) days, respectively, in RRV infected mice. A lower dose (0.1 mg/kg) or a higher dose (8 mg/kg) had no significant effect on NDD. No synergistic effect was seen when the VIP antagonist (1.5 mg/kg) and granisetron (2 mg/kg) were administered together.

Figure 3.

Number of days with diarrhoea (NDD) after treatment of rotavirus infected mice with the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist granisetron, the 5-HT4 receptor antagonist RS 39604, or a combination of a vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor antagonist (VIPa) (1.5 mg/kg) and granisetron (2 mg/kg) (Granis+VIP). Non-treated rotavirus infected mice served as controls. Values in columns indicate the number of mice. Values are means (SEM). *p<0.05, **p<0.01 compared with controls (Student’s t test).

Mice treated with granisetron showed a similar profile as those treated with the VIP receptor antagonist (fig 2 ▶), with the difference that granisetron treated mice resolved diarrhoea one day earlier.

Rotavirus induced diarrhoea was unaffected by the 5-HT4 receptor antagonist RS 39604 at the given dose range (fig 3 ▶).

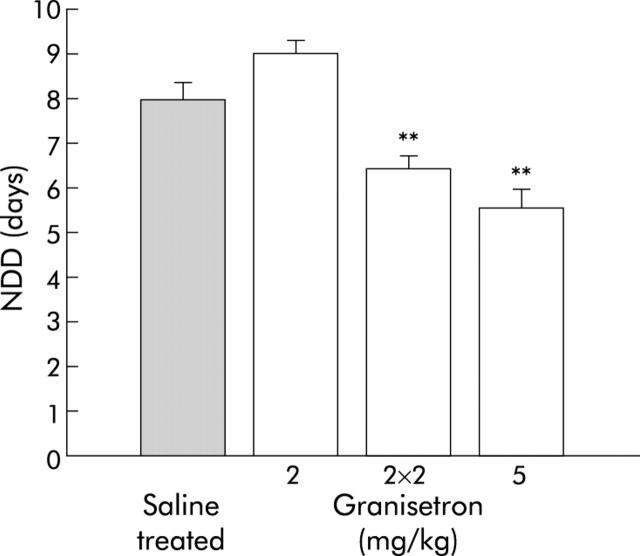

Effect of granisetron on EDIM infected mice

In order to exclude the possibility that the inhibitory effect of the drugs was limited only to a heterologous rotavirus strain, granisetron was given to EDIM infected Balb/c mice. As illustrated in fig 4 ▶, EDIM evoked diarrhoea that lasted for 8.0 (0.4) days. EDIM infected mice treated with 5 mg/kg of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist granisetron had a significantly shorter duration of diarrhoea (5.6 (0.4) days; p<0.01) compared with untreated mice and mice treated with 2 mg/kg granisetron.

Figure 4.

Comparison between saline treated and granisetron treated EDIM infected mice. Granisetron was given at a dose of 2 or 5 mg/kg/day or 2 mg/kg twice a day (2×2 mg/kg). Values are means (SEM). **p<0.01 compared with controls (Student’s t test).

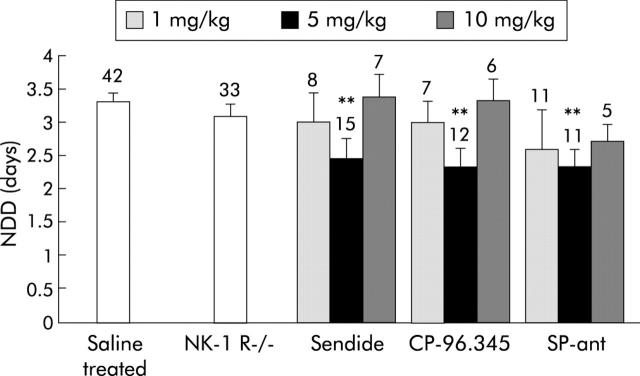

Role of tachykinin on rotavirus induced diarrhoea

The SP receptor antagonist (D-Pro2, D-Trp7, 9)-SP decreased the duration of diarrhoea to 2.7 (0.2) (95% CI 2.19–3.25) (10 mg/kg), 2.3 (0.3) (95% CI 1.76–2.89) (5 mg/kg), and 2.6 (0.6) (95% CI 0.93–4.2) (1 mg/kg) days but this was statistically significant only with the 5 mg/kg dose (fig 5 ▶). If the data from the three doses are pooled, the effect is significant but less pronounced (2.5 (0.2) days; n = 28; p<0.01).

Figure 5.

Effect of substance P (SP) on the number of days with rotavirus diarrhoea (NDD). SP receptor antagonism was studied using neurokinin 1 receptor knockout mice (NK-1 R−/−), the SP receptor antagonist (D-Pro2, D-Trp7, 9)-SP (SP-ant), and NK-1 receptor antagonists (Sendide and CP-96,345). Values above the columns indicate the number of mice. Values are means (SEM). **p<0.01 compared with controls (Student’s t test).

To examine if the NK-1 receptor participates in rotavirus induced diarrhoea, Balb/c mice were given RRV and two different antagonists for the NK-1 receptor—Sendide and CP-96,345. Figure 5 ▶ shows that Sendide did not have any significant effect at a dose of 1 or 10 mg/kg but reduced the duration of diarrhoea to 2.5 (0.3) days (p<0.01) at a dose of 5 mg/kg. Similarly, CP-96,345 reduced the duration of diarrhoea to 2.3 (0.3) days (95% CI 1.84–3.08) (p<0.01) at a dose of 5 mg/kg. Its inactive enantiomer CP-96,344 (5 mg/kg) did not have any effect (data not shown).

Effects of rotavirus and CT in NK-1 receptor knockout mice

To further investigate the role of the NK-1 receptor in secretory diarrhoea, RRV and CT (3 mg/kg) were given to NK-1R−/− mice. The absence of the NK-1 receptor in the small intestine of knockout mice was confirmed (data not shown) by immunohistochemistry, as previously reported.8 While CT induced diarrhoea was significantly attenuated in NK-1R−/− mice compared with control Balb/c mice, no effect was seen on rotavirus infected NK-1R−/− mice. Of the 42 knockout mice given CT, 13 (30%) developed diarrhoea within 12 hours compared with 21 of 24 (88%) for wild-type Balb/c mice. Of the 33 NK-1R−/− mice given RRV, all developed diarrhoea and NDD was 3.1 (0.2) days (95% CI 2.74–3.43) compared with 3.3 (0.2) days for control mice (fig 5 ▶).

DISCUSSION

We have previously reported that rotavirus activates the ENS.11 The main objective of this work was to identify the specific neurotransmitters involved in clinical rotavirus diarrhoea. The principle and novel finding was that rotavirus diarrhoea was attenuated by a VIP receptor and 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating an effect of specific neurotransmitter blockade on gastroenteritis. Diarrhoea was attenuated and not completely blocked, which preserves the physiological role of diarrhoea as a defence mechanism.

When interpreting the data it is convenient to discuss the results in terms of site of interaction with the postulated secretomotor reflex. Starting with the final secretomotor neurone, two neurotransmitters, VIP and acetylcholine, have been inferred to be important for the nervous control of the intestinal fluid secretion in crypts.10 Therefore, the effects of a VIP receptor antagonist and the muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine on rotavirus diarrhoea were tested. The data suggest that rotavirus activates VIPergic but not cholinergic secretomotor neurones.

The VIP receptor antagonist (4Cl-D-Phe6,Leu17)-VIP has also been reported to attenuate CT and Escherichia coli heat labile toxin induced secretion in perfusion experiments in vivo in rats.15 In the present experiments, a considerably higher dose was used than in the cited study. This was based on the following considerations. Although the pharmacokinetics of the VIP receptor antagonist are not known, it seems reasonable to assume that the half life of the drug in mice puppies (weight approximately 3 g) is considerably shorter than in rats (weight approximately 200 g). Furthermore, in the study by Mourad and Nassar,19 the drug was continuously infused intravenously in short term experiments. Finally, by giving a high dose, the number of intraperitoneal injections could be limited, avoiding stress to the mice.

More than 80% of the total 5-HT content in the body is localised in the gastrointestinal tract, mainly in enterochromaffin cells. The 5-HT3 receptor is a widely distributed receptor in the ENS and is most likely the main mediator of the serotonin effect on intestinal secretion.20 A role for 5-HT, in particular the 5-HT3 receptor, in fluid secretion evoked by CT and Salmonella typhimurium has been established.21,22 Granisetron is a highly specific 5-HT3 receptor inhibitor with no 5-HT4 receptor agonist activity, unlike many other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists. The role of granisetron in rotavirus diarrhoea was evaluated in this study. The drug was administered in the same dose range as previously described for mice23 and was shown to attenuate rotavirus diarrhoea.

RRV induced NDD concentration-response curve for VIP receptor antagonist and granisetron had a bell shape appearance (fig 3 ▶). These results may reflect desensitisation or downregulation of the number of 5-HT3 and VIP receptors or that the high concentration of the drug interfered with receptors resulting in an agonist effect. A bell shaped dose-response curve for serotonin and granisetron has been reported previously.24,25. Higher doses of granisetron were needed in EDIM infected mice in order to obtain a clinical effect which could have been due to the fact that EDIM stimulates a more pronounced diarrhoea and thus requires a higher therapeutic dose. When the 5-HT3 antagonist and the VIP antagonist were administrated together a synergistic effect was absent. This may be explained by serotonin and VIP acting via the same intramural neural reflex but at different sites, as described in the introduction.

The present methodology cannot discriminate per se between the antisecretory effects and effects secondary to, for example, transit time changes or motor function. However, although an inhibitory action of a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, ondansetron, on normal colonic transit has been described in the literature,26 several other studies have not shown any effect of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists on the motor response of the gut or basal transport.27,28 Also, if increased transit time is the mechanism, one would have expected a marked effect of the muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine, which was not the case. In the 5-HT induced motor stimulatory response, 5-HT4 and not 5-HT3 receptors have been suggested to be the main mediators.27,29 Furthermore, the effects of 5-HT on motor responses seem to involve enteric cholinergic (muscarinic) transmission.27,30 As no effect on clinical diarrhoea was seen with the 5-HT4 receptor antagonist and the muscarinic antagonist atropine, an effect secondary to motor inhibition does not seem to account for the effect of granisetron.

Recently it has emerged that the 5-HT4 receptor may also be important in 5-HT induced intestinal secretion.31 5-HT4 receptors are present on non-neural cells and motorneurones of the myenteric plexus. We used the 5-HT4 receptor antagonist RS 39604 as it is reported to have the longest biological half life among the specific 5-HT4 receptor antagonists.32 In contrast with CT induced secretion, the 5-HT4 receptor antagonist had no effect on rotavirus diarrhoea, suggesting that 5-HT4 receptors are not involved in rotavirus fluid secretion.

SP is a peptide widely distributed throughout the central and peripheral nervous system in the intestinal tract and has been found in enteric neurones, capsaicin sensitive neurones, and in intestinal enterochromaffin cells.33 SP interacts with three neurokinin receptors (NK-1, NK-2, and NK-3) with the highest affinity for NK-1 receptors, which are abundant in the intrinsic enteric neurones, interstitial cells of Cajal, and in the spinal cord. Studies of the role of SP in fluid secretion have been hampered by the lack of specific receptor blockers. Hence in order to address the role of SP involvement, in particular the NK-1 receptor, in rotavirus diarrhoea, several different antagonists were tested, as well as NK-1 knockout mice. The SP receptor antagonist (D-Pro2, D-Trp7, 9)-SP is a synthetic peptide analogue of SP with a minor amino acid substitution.34 Although this type of tachykinin antagonist has some specificity of action, it has major drawbacks, such as low potency.33 While CP-96,345, a non-peptide tachykinin antagonist, is more selective for the NK-1 receptor than for the other receptors, it exhibits a species related difference in affinity and has been suggested to exert non-selective neural effects.35 We included the inactive enantiomer CP-96,344 in order to distinguish possible unspecific effects. Sendide is a novel peptide antagonist, highly selective for the NK-1 receptor,36 although it exerts an opioid activity at high doses.37

CT induced fluid secretion, but not secretion by Escherichia coli enterotoxins, has been reported to be inhibited by the tachykinin antagonists (D-Pro2, D-Trp7,9)-SP, Sendide, and CP-96,345.38 Castagliuolo et al performed extensive work on the involvement of the NK-1 receptor in Clostridium difficile toxin A induced secretion and inflammation using CP-96,345 or NK-1 knockout mice.39 This group did not observe any inhibitory action of CP-96,345 on CT evoked secretion.

In the present study, CT induced intestinal secretion was reduced in NK-1 receptor knockout mice but there was no effect on rotavirus induced diarrhoea. The results with CT in the present study and the previous effect seen with Clostridium difficile toxin39 suggest this knockout mouse model to be useful. However, to further confirm the role of the NK-1 receptor, the effect of the SP antagonist was investigated. Considering all of the antagonists used, only the intermediate dose had a small but significant effect. This added to the negative observation with the knockout model, indicating that the role of SP in the neural mechanism for rotavirus diarrhoea may be modest. The discrepancy between the antagonists and the knockout model may also be explained by a modest role of SP in the pathogenesis so that when NK-1 receptors are lacking other regulatory mechanisms take over.

While our previous study with tetrodotoxin indicated that the main mechanism of rotavirus induced fluid secretion could be ascribed to neuronal involvement,11 less pronounced effects were found with specific antagonists for 5-HT and VIP. A reasonable explanation for these differences could be that additional neurotransmitters participate in rotavirus diarrhoea. Indeed, a dramatic effect on rotavirus fluid secretion was recently reported in galanin-1 knockout mice (Shaw RD, et al. DDW 2002, abstract 638). Furthermore, a secretory neuronal mechanism for rotavirus diarrhoea is supported by Salazar-Lindo and colleagues40 who showed attenuation of rotavirus diarrhoea in children with racecadotril, a drug that prevents the action of enkephalinase. Enkephalins are known to be inhibitory neurotransmitters which act on activated secretory neural reflex pathways and crypt cells.41 A further more likely possibility is that replicating rotavirus could impair cellular functions and thus impair salt and water absorption.42–45 For example, rotavirus infection is suggested to result in epithelial dysfunction, including reduction of expression of digestive enzymes,42 inhibition of Na+-solute symport systems,43 and impaired intestinal permeability.44,45 Furthermore, the suggested NSP4 enterotoxin is capable of inducing diarrhoea in mice.46

In conclusion, we have shown that the neurotransmitters serotonin and VIP are involved in rotavirus diarrhoea, observations that improve our current knowledge of the pathophysiology of viral gastroenteritis. The data may imply new principles for the treatment of this disease with significant global impact. The exact site of action of the neurotransmitters is still unclear. There are ongoing studies on enterochromaffin cells and rotavirus in our laboratory in order to further map these mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the Swedish Research Council (grants 10392/10A). Professor Susanne Holmgren and co-workers are acknowledged for valuable help with immunohistochemistry.

Abbreviations

CT, cholera toxin

ENS, enteric nervous system

NK-1, neurokinin 1

NK-1R−/−, neurokinin 1 receptor knockout mouse

NDD, total number of days with diarrhoea

RRV, rhesus rotavirus

5-HT3, serotonin 3

SP, substance P

VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide

REFERENCES

- 1.Bern C , Martines J, de Zoysa I, et al. The magnitude of the global problem of diarrhoeal disease: a ten-year update. Bull World Health Organ 1992;70:705–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estes MK, Morris AP. A viral enterotoxin. A new mechanism of virus-induced pathogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol 1999;473:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Estes MK. The rotavirus NSP4 enterotoxin: current status and challenges. In: Desselberger U, Gray J, eds. Viral gastroenteritis. Perspectives in medical virology, vol 9 2003:207–224.

- 4.Cooke HJ. “Enteric tears”: chloride secretion and its neural regulation. News Physiol Sci 1998;13:269–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jodal M , Lundgren O. Neural reflex modulation of intestinal epithelial transport. In: Gaginella TS, ed. Regulatory mechanisms in gastrointestinal function. B. oca Raton: CRC Press, 1995:99–144.

- 6.Pothoulakis C , Lamont JT. Microbes and microbial toxins: paradigms for microbial-mucosal interactions II. The integrated response of the intestine to Clostridium difficile toxins. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2001;280:G178–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brookes SJ. Classes of enteric nerve cells in the guinea-pig small intestine. Anat Rec 2001;262:58–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carey HV, Cooke HJ. Neuromodulation of intestinal transport in the suckling mouse. Am J Physiol 1989;256:R481–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holzer P , Holzer-Petsche U. Tachykinin receptors in the gut: physiological and pathological implications. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2001;1:583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hubel KA. Intestinal nerves and ion transport: stimuli, reflexes, and responses. Am J Physiol 1985;248:G261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundgren O , Peregrin AT, Persson K, et al. Role of the enteric nervous system in the fluid and electrolyte secretion of rotavirus diarrhea. Science 2000;287:491–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bozic CR, Lu B, Hopken UE, et al. Neurogenic amplification of immune complex inflammation. Science 1996;273:1722–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng N , Burns JW, Bracy L, et al. Comparison of mucosal and systemic humoral immune responses and subsequent protection in mice orally inoculated with a homologous or a heterologous rotavirus. J Virol 1994;68:7766–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruggeri FM, Johansen K, Basile G, et al. Antirotavirus immunoglobulin A neutralizes virus in vitro after transcytosis through epithelial cells and protects infant mice from diarrhea. J Virol 1998;72:2708–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Offit P , Clark H, Kornstein M, et al. A murine model for oral infection with a primate rotavirus (Simian SA11). J Virol 1984;51:233–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward R , McNeal M, Sheridan J. Development of an adult mouse model for studies on protection against rotavirus. J Virol 1990;64:5070–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassidy J , Raina V, Lewis C, et al. Pharmacokinetics and anti-emetic efficacy of BRL43694, a new selective 5HT-3 antagonist. Br J Cancer 1988;58:651–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vannucchi MG, Faussone-Pellegrini MS. NK1, NK2 and NK3 tachykinin receptor localization and tachykinin distribution in the ileum of the mouse. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2000;202:247–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mourad FH, Nassar CF. Effect of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) antagonism on rat jejunal fluid and electrolyte secretion induced by cholera and Escherichia coli enterotoxins. Gut 2000;47:382–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansen MB, Skadhauge E. Signal transduction pathways for serotonin as an intestinal secretagogue. Comp Biochem Physiol A Physiol 1997;118:283–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beubler E , Horina G. 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptor subtypes mediate cholera toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion in the rat. Gastroenterology 1990;99:83–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen GM, Grondahl ML, Nielsen CG, et al. Effect of ondansetron on Salmonella typhimurium-induced net fluid accumulation in the pig jejunum in vivo. Comp Biochem Physiol A Physiol 1997;118:297–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourin M , Hascoet M, Deguiral P. 5-HTP induced diarrhea as a carcinoid syndrome model in mice? Fundam Clin Pharmacol 1996;10:450–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langlois A , Pascaud X, Junien JL, et al. Response heterogeneity of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in a rat visceral hypersensitivity model. Eur J Pharmacol 1996;318:141–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silva SR, Futuro-Neto HA, Pires JG. Effects of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists on neuroleptic-induced catalepsy in mice. Neuropharmacology 1995;34:97–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gore S , Gilmore IT, Haigh CG, et al. Colonic transit in man is slowed by ondansetron (GR38032F), a selective 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor (type 3) antagonist. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1990;4:139–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kadowaki M , Nagakura Y, Tomoi M, et al. Effect of FK1052, a potent 5-hydroxytryptamine3 and 5-hydroxytryptamine4 receptor dual antagonist, on colonic function in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1993;266:74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turvill JL, Mourad FH, Farthing JG. Crucial role for 5-HT in cholera toxin but not Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin-intestinal secretion in rats. Gastroenterology 1998;115:883–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagakura Y , Ito H, Kiso T, et al. The selective 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)4-receptor agonist RS67506 enhances lower intestinal propulsion in mice. Jpn J Pharmacol 1997;74:209–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Briejer MR, Schuurkes JA. 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors and cholinergic and tachykininergic neurotransmission in the guinea-pig proximal colon. Eur J Pharmacol 1996;308:173–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hedge SS, Moy TM, Perry MR, et al. Evidence for the involvement of 5-hydroxytryptamine 4 receptors in 5-hydroxytryptophan-induced diarrhea in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1994;271:741–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hegde SS, Bonhaus DW, Johnson LG, et al. RS 39604: a potent, selective and orally active 5-HT4 receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol 1995;115:1087–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maggi CA, Patacchini R, Rovero P, et al. Tachykinin receptors and tachykinin receptor antagonists. J Auton Pharmacol 1993;13:23–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engberg G , Svensson TH, Rosell S, et al. A synthetic peptide as an antagonist of substance P. Nature 1981;293:222–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Regoli D , Boudon A, Fauchere JL. Receptors and antagonists for substance P and related peptides. Pharmacol Rev 1994;46:551–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakurada T , Manome Y, Tan-No K, et al. A selective and extremely potent antagonist of the neurokinin-1 receptor. Brain Res 1992;593:319–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakurada T , Yuhki M, Inoue M, et al. Opioid activity of sendide, a tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol 1999;369:261–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turvill JL, Connor P, Farthing MJ. Neurokinin 1 and 2 receptors mediate cholera toxin secretion in rat jejunum. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1037–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castagliuolo I , Riegler M, Pasha A, et al. Neurokinin-1 (NK-1) receptor is required in Clostridium difficile-induced enteritis. J Clin Invest 1998;101:1547–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salazar-Lindo E , Santisteban-Ponte J, Chea-Woo E, et al. Racecadotril in the treatment of acute watery diarrhea in children. N Engl J Med 2000;343:463–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turvill J , Farthing M. Enkephalins and enkephalinase inhibitors in intestinal fluid and electrolyte transport. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1997;9:877–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jourdan N , Brunet JP, Sapin C, et al. Rotavirus infection reduces sucrase-isomaltase expression in human intestinal epithelial cells by perturbing protein targeting and organization of microvillar cytoskeleton. J Virol 1998;72:7228–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Halaihel N , Lievin V, Alvarado F, et al. Rotavirus infection impairs intestinal brush-border membrane Na(+)-solute cotransport activities in young rabbits. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2000;279:G587–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dickman KG, Hempson SJ, Anderson J, et al. Rotavirus alters paracellular permeability and energy metabolism in caco-2 cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2000;279:G757–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tafazoli F , Zeng CQ, Estes MK, et al. NSP4 enterotoxin of rotavirus induces paracellular leakage in polarized epithelial cells. J Virol 2001;75:1540–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ball JM, Tian P, Zeng CQ, et al. Age-dependent diarrhea induced by a rotaviral nonstructural glycoprotein. Science 1996;272:101–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]