Abstract

Background and aims: Stress often worsens the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). We hypothesised that this might be explained by altered neuroendocrine and visceral sensory responses to stress in IBS patients.

Subjects and methods: Eighteen IBS patients and 22 control subjects were assessed using rectal balloon distensions before, during, and after mental stress. Ten controls and nine patients were studied in supplementary sessions. Rectal sensitivity (thresholds and intensity—visual analogue scale (VAS)) and perceived stress and arousal (VAS) were determined. Plasma levels of corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), cortisol, noradrenaline, and adrenaline were analysed at baseline, immediately after stress, and after the last distension. Heart rate was recorded continuously.

Results: Thresholds were increased during stress in control subjects (p<0.01) but not in IBS patients. Both groups showed lower thresholds after stress (p<0.05). Repeated distensions without stress did not affect thresholds. Both groups showed increased heart rate (p<0.001) and VAS ratings for stress and arousal (p<0.05) during stress. Patients demonstrated higher ratings for stress but lower for arousal than controls. Basal CRF levels were lower in patients (p<0.05) and increased significantly during stress in patients (p<0.01) but not in controls. Patients also responded with higher levels of ACTH during stress (p<0.05) and had higher basal levels of noradrenaline than controls (p<0.01). Controls, but not patients, showed increased levels of adrenaline and noradrenaline in response to stress (p<0.05).

Conclusions: Stress induced exaggeration of the neuroendocrine response and visceral perceptual alterations during and after stress may explain some of the stress related gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS.

Keywords: stress, irritable bowel syndrome, rectal sensitivity, neuroendocrine response

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common disorder in Western populations.1 Patients often describe a correlation between stressful life events and the onset or exacerbation of their gastrointestinal symptoms. Also, IBS patients seem more susceptible to the stressful events of daily life.2 However, the relationship between stress and symptoms in IBS are incompletely understood.

Various stressors induce characteristic changes in gastrointestinal motor function.3–5 Moreover, manipulation of attention and changes in arousal level produced by stress, distraction, and relaxation has been reported to alter visceral perception.6–12 However, previous studies on stress and visceral perception have shown contradictory results. Moreover, it is not known if the effects of stress on visceral sensitivity differ between healthy controls and patients with IBS.

The central nervous system response to stress modulates autonomic nervous system outflow and activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.13 Dysfunction of these systems has been proposed to be an aetiological mechanism in IBS.14,15 Differences between IBS patients and healthy subjects regarding levels of hormones involved in the stress response have been reported.15 In addition, corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), which is also believed to play an important role in the stress response,16 induced higher levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), as well as more profound enhancement of colonic motility in IBS patients compared with healthy controls.17 Also, CRF has been shown to increase rectal sensitivity.18 Thus alterations in the neuroendocrine response to stress may be of importance in the pathophysiology of IBS.19

To further explore the link between mental stress and the pathophysiology of IBS, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the effects of acute mental stress on rectal sensitivity and hormones involved in the stress response in IBS patients and in healthy controls. We hypothesised that IBS patients would exhibit an exaggerated neuroendocrine response and increased rectal sensitivity when exposed to stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Patients with a clinical diagnosis of IBS, based on the ROME II criteria,20 were recruited from our outpatient clinic. Healthy controls with no history of gastrointestinal symptoms were recruited by advertisement and completed a bowel symptom questionnaire to ensure exclusion of IBS non-patients. All subjects gave informed consent. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Göteborg.

Mental stress

Acute mental stress was provoked with a colour word conflict test (Stroop test)21–23 and a mental arithmetic test. In the Stroop test, subjects were asked to rapidly, at a pace set by a metronome, identify the colours in which words representing colours were printed (for example, the word red presented in the colour green, the correct response being green). The stress period lasted approximately 10 minutes during which time subjects were exposed to the Stroop test for 3–4 minutes, mental arithmetic test for 2–3 minutes, and the Stroop test again for 3–4 minutes. To induce performance pressure, subjects were told that accuracy was monitored and approximately once every minute told that correct answers were incorrect. Levels of experienced stress and arousal were evaluated using 100 mm visual analogue scales (VAS): two scales anchored tired–energetic and active–drowsy for levels of arousal, and two scales anchored peaceful–tense and worried–relaxed for levels of stress.24,25 In addition, we continuously monitored the subject’s heart rate using a pulse oximeter (Oscar/oxy, Datex; Dansjö/Omega, Solna, Sweden).

Rectal distensions

Rectal sensitivity was tested with balloon distensions using a computer driven electronic barostat (Dual Drive Barostat, Distender Series II; G&J Electronics Inc., Toronto, Canada). A highly compliant polyethylene balloon was attached to a double lumen polyvinyl tube (Salem Sump Tube, 18F; Sherwood Medical, Tullamore, Ireland) and tied at both ends (8 cm between attachment sites). Distension to the maximal volume (550 ml) resulted in a spherical shape. The distension protocol consisted of phasic distensions (45 ml/s) with semi randomly ascending pressures (15–10–25–20–35–30–45–40–50 mm Hg).26 Each distension lasted 30 seconds followed by a 30 second resting interval at 5 mm Hg. During the last 10 seconds of each distension, subjects rated any perceived sensation on a panel graded 1–5 representing: (1) no sensation; (2) rectal fullness; (3) urge to defecate; (4) discomfort; and (5) pain. If the subject reported pain prior to the last distension (50 mm Hg), the protocol was interrupted. Sensory thresholds were determined for rectal fullness, urge to defecate, discomfort, and pain. Subjects rated experienced intensities of discomfort and pain on two separate 100 mm VAS anchored no discomfort/pain–worst imaginable discomfort/pain. Balloon volumes were monitored during distensions allowing comparison of pressure-volume curves (compliance).

Procedures

No medications with known gastrointestinal effects were allowed within 48 hours before the study. All studies were started at 1 pm in order to control for circadian variations in hormone levels. Subjects were instructed to have breakfast no later than 7 am and thereafter refrain from oral intake. After bowel cleansing with a tap water enema (500 ml), subjects were equipped with an intravenous cannula and placed in a left lateral decubitus position. The lubricated balloon was then inserted into the rectum (distal attachment site 5 cm from the anal verge). After connecting the balloon catheter to the barostat, two distensions were performed at 20 mm Hg to unfold the balloon before leaving it at a baseline pressure of 5 mm Hg. This was followed by a 30 minutes stabilisation period before commencing the experiment.

Study design

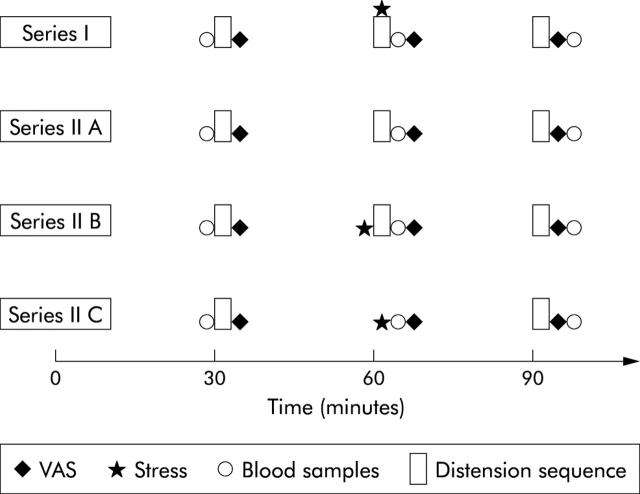

Two series of studies (I and II) with the same preparations and similar set up (fig 1 ▶) were performed. In series I, 22 healthy controls (13 females; mean age 35.3 years (range 22–70)) and 18 IBS patients (12 females; mean age 42.7 years (range 24–71); five diarrhoea predominant (IBS-D), seven constipation predominant (IBS-C), and six alternating type IBS (IBS-A)) underwent three distension sequences (1, 2, and 3) as described above, each sequence being followed by 20 minutes of rest at the baseline pressure. The second distension sequence was carried out with ongoing stress.

Figure 1.

Experiment protocol (see text for details). VAS, visual analogue scale.

In series II, 10 healthy controls (seven females; mean age 28.5 years (range 22–58)) and nine IBS patients (eight females; mean age 36.7 years (range 26–61); three IBS-D, three IBS-C, and three IBS-A) were studied during three separate sessions (A, B, and C). This was done in attempt to separate the effects of stress from the effects of repeated distensions on rectal sensitivity.

Three consecutive distension sequences (1, 2, and 3) separated by 20 minute resting periods (providing results on effects of multiple distensions alone).

Three distension sequences (1, 2, and 3) separated by 20 minute resting periods; the second sequence following immediately after a 10 minute stress period (eliminating possible effects of distraction).

Two distension sequences (1 and 2) separated by 20 minutes of rest, 10 minutes of stress, and an additional 20 minutes of rest (giving information on the late effects of stress).

The order of the sessions was randomised for each subject.

Blood samples for analysis of plasma levels of CRF, ACTH, cortisol, adrenaline, and noradrenaline were obtained before the first distension sequence and immediately after the second and third sequences. In series II C, the second set of samples were obtained after the stress period. VAS for stress, arousal, discomfort, and pain were administered immediately after each distension sequence. Heart rate was monitored continuously. All subjects completed the hospital anxiety and depression (HAD) scale27 and the Spielberger state trait anxiety inventory (STAI).28

Biochemical assays

Blood samples were immediately centrifuged at 3800 g at 4°C for 10 minutes. The supernatant was aspirated and stored at −20°C (CRF, ACTH, and cortisol) or −80°C (adrenaline and noradrenaline) until analysis. Radioimmunoassays for CRF were performed in duplicate according to Ekman and colleagues.29 Concentrations of ACTH were determined with reagents from Euro-Diagnostics (Malmö, Sweden). Cortisol was measured using a commercial RIA (Orion Diagnostica AB, Sweden). Analysis of catecholamines, adrenaline, and noradrenaline were performed by high performance liquid chromatography according to Holly and Makin.30

Data analysis

The Protocol Plus software package (G&J Electronics Inc., Toronto, Canada) was used for data analysis. Sensory thresholds (both pressure and volume) were compared between distension sequences in both patients and controls. If pain was not experienced, the pain threshold was set to a maximum pressure of 50 mm Hg. Compliance (pressure-volume relationship) was evaluated for each distension sequence by plotting the volume against the corresponding pressure level and was then compared between groups and distension sequences. Heart rate was monitored continuously, recording a value every 10 seconds. A mean value for each distension sequence and resting period was calculated and compared. Plasma levels of hormones were analysed for differences between groups and distension sequences. Blood samples from series I experiments were analysed together with samples from series II B. VAS ratings for discomfort, pain, stress, and arousal from series I experiments were compared between distension sequences and groups. HAD and STAI scores were compared for group differences and correlation with hormone levels and sensory thresholds.

Statistical analysis

Thresholds, heart rate, and hormones levels are expressed as mean (SEM). Comparisons of thresholds, heart rate, and blood samples between groups and between the different distension sequences were made using paired and unpaired t tests, respectively. Results from VAS, HAD, and STAI are expressed as median (interquartile range (IQR)). VAS, HAD, and STAI scores were compared using Wilcoxon’s sign test and the Mann-Whitney U test. Correlation between HAD and STAI and sensory thresholds, blood samples, and stress and arousal scores were investigated using the Spearman rank test. Compliance curves were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA). A significance level of 0.05 was accepted.

RESULTS

Sensory thresholds

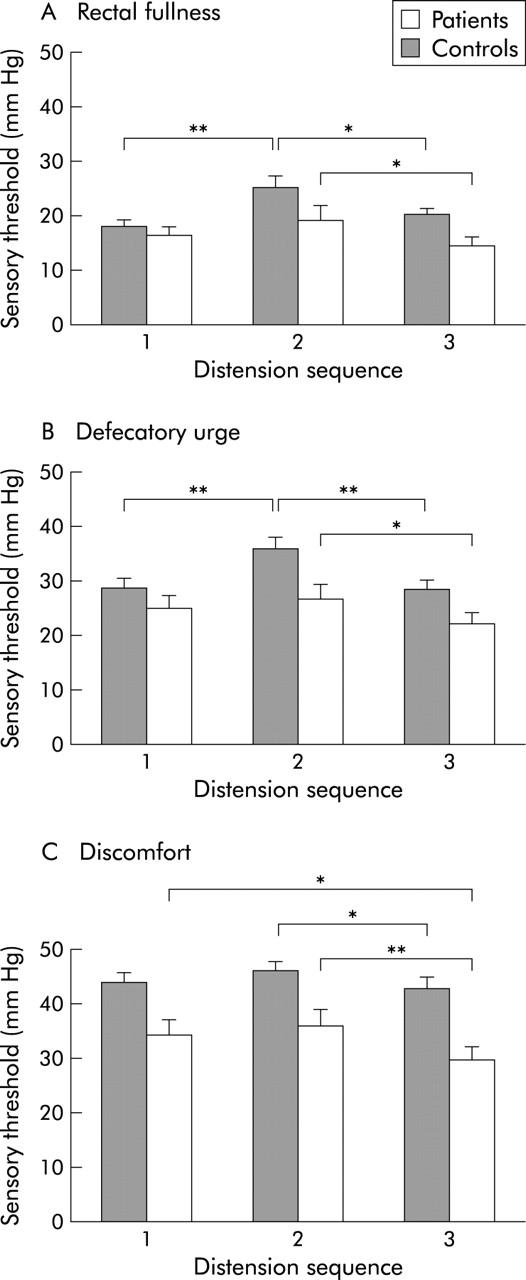

Series I (three distensions sequences, second sequence with ongoing stress) (fig 2 ▶)

Figure 2.

Sensory thresholds (mean (SEM)) for rectal fullness (A), defecatory urge (B), and discomfort (C) during the distension sequences before stress (1), during stress (2), and after stress (3) in series I experiments in patients and controls. Thresholds were increased in controls during stress compared with before and after. In patients, only thresholds after stress differed from the stress period. *p<0.05 **p<0.01.

Sensory thresholds were increased in healthy controls during stress compared with before and after stress (2 v 1 and 3) for rectal fullness (p = 0.003; p = 0.03), urge to defecate (p = 0.007; p = 0.003), and discomfort (p = 0.1; p = 0.02). Few controls reported pain at the maximum pressure of 50 mm Hg, making comparisons for pain inconclusive. IBS patients had lower thresholds after stress compared with during stress (2 v 3) for all studied sensations (rectal fullness p = 0.02; urge to defecate p = 0.03; discomfort p = 0.008), including pain (43.6 (1.9) v 41.1 (2.3) mm Hg; p = 0.02). No significant differences were seen between thresholds before and during stress (1 v 2). Sensory thresholds for urge to defecate and discomfort were lower during the last distension sequence compared with the first (3 v 1) in patients (p = 0.07; p = 0.04) but not in controls. Using the corresponding volume instead of pressure at the sensory thresholds yielded similar results (data not shown). Compliance was lower in IBS compared with controls before stress (p = 0.02) but was not affected by stress (data not shown). Based on VAS, perceived discomfort and pain during distensions were greater in patients than in controls (p<0.01). However, no major effects of stress on perceived intensities of discomfort and pain during distensions were observed (table 1 ▶).

Table 1.

Perceived intensities

| Distension sequence | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Discomfort (VAS) | |||

| Control | 29 (13–49) | 19 (8–32) | 24 (10–45) |

| IBS | 60 (39–73)†† | 56 (45–70)†† | 64 (45–78)†† |

| Pain (VAS) | |||

| Control | 1 (0–12) | 0 (0–10)* | 0 (0–13) |

| IBS | 38 (0–64)*†† | 18 (0–67)†† | 52 (7–67)†† |

VAS, visual analogue scale.

VAS for discomfort and pain (mm; median (interquartile range)) during the distension sequences before (1), during (2) and after stress (3) in series I experiments.

*p<0.05 versus sequence 3; ††p<0.01 versus controls.

Series II A (distensions without stress)

Repeated distensions without stress had little effect on sensory thresholds in both groups. Lower pain thresholds during the third distension sequence were observed in patients (p = 0.04) (table 2 ▶).

Table 2.

Sensory thresholds in series II A experiments

| Distension sequence | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Fullness (mm Hg) | |||

| Control | 24.0 (1.6) | 22.5 (1.3) | 21.5 (2.5) |

| IBS | 14.3 (1.7) | 17.5 (1.9) | 15.6 (2.2) |

| Urge to defecate (mm Hg) | |||

| Control | 36.0 (2.8) | 35.0 (3.0) | 33.0 (2.6) |

| IBS | 21.9 (2.5) | 23.1 (2.5) | 23.8 (2.8) |

| Discomfort (mm Hg) | |||

| Control | 46.0 (1.6) | 45.5 (1.9) | 43.5 (2.4) |

| IBS | 31.3 (3.6) | 30.0 (3.9) | 29.4 (3.8) |

| Pain (mm Hg) | |||

| Control | 50.0 (0) | 50.0 (0) | 50.0 (0) |

| IBS | 39.4 (4.1) | 38.8 (4.0) | 33.1 (3.7)* |

Sensory thresholds (mean (SEM)) during distension sequences 1, 2, and 3 in series II A experiments in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients and controls.

*p<0.05 versus sequence 1.

Series II B (three distension sequences, stress before the second distension sequence)

In patients and to some extent in controls, thresholds tended to decrease during the last distension sequence. More specifically, in patients, lower thresholds were seen during the last distension for rectal fullness (p = 0.002), discomfort (p = 0.01), and pain (p = 0.08) (table 3 ▶).

Table 3.

Sensory thresholds in series II B experiments

| Distension sequence | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Fullness (mm Hg) | |||

| Control | 24.4 (3.8) | 25.6 (2.9)† | 23.1 (2.7) |

| IBS | 15.0 (1.2) | 21.7 (1.4)** | 15.0 (1.7) |

| Urge to defecate (mm Hg) | |||

| Control | 36.3 (3.4) | 36.3 (3.0) | 36.3 (3.8) |

| IBS | 25.0 (2.0) | 25.0 (2.4) | 23.9 (1.8) |

| Discomfort (mm Hg) | |||

| Control | 45.6 (1.8) | 46.3 (1.8) | 43.1 (2.8) |

| IBS | 37.8 (3.1)† | 35.6 (3.7)† | 31.7 (3.8) |

| Pain (mm Hg) | |||

| Control | 50.0 (0) | 50.0 (0) | 50.0 (0) |

| IBS | 42.8 (2.5) | 42.8 (2.8) | 39.4 (3.8) |

Sensory thresholds (mean (SEM)) during distension sequences 1, 2, and 3 in series II B experiments in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients and controls.

**p<0.01 versus sequences 1 and 3; †p<0.05 versus sequence 3.

Series II C (two distension sequences separated by stress)

No changes in thresholds were observed in any of the groups (table 4 ▶).

Table 4.

Sensory thresholds in series II C experiments

| Distension sequence | ||

| 1 | 2 | |

| Fullness (mm Hg) | ||

| Control | 21.0 (1.8) | 21.5 (1.8) |

| IBS | 16.9 (2.3) | 15.6 (1.5) |

| Urge to defecate (mm Hg) | ||

| Control | 35.0 (2.4) | 31.5 (2.8) |

| IBS | 25.6 (2.0) | 25.0 (1.9) |

| Discomfort (mm Hg) | ||

| Control | 44.5 (1.9) | 45.5 (2.4) |

| IBS | 34.4 (2.6) | 31.9 (3.1) |

| Pain (mm Hg) | ||

| Control | 50.0 (0) | 50.0 (0) |

| IBS | 44.4 (3.2) | 43.1 (3.7) |

Sensory thresholds (mean (SEM)) during distension sequences 1 and 2 in series II C experiments in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients and controls.

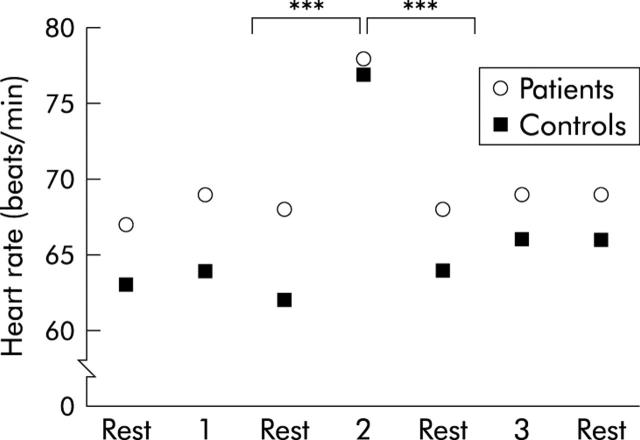

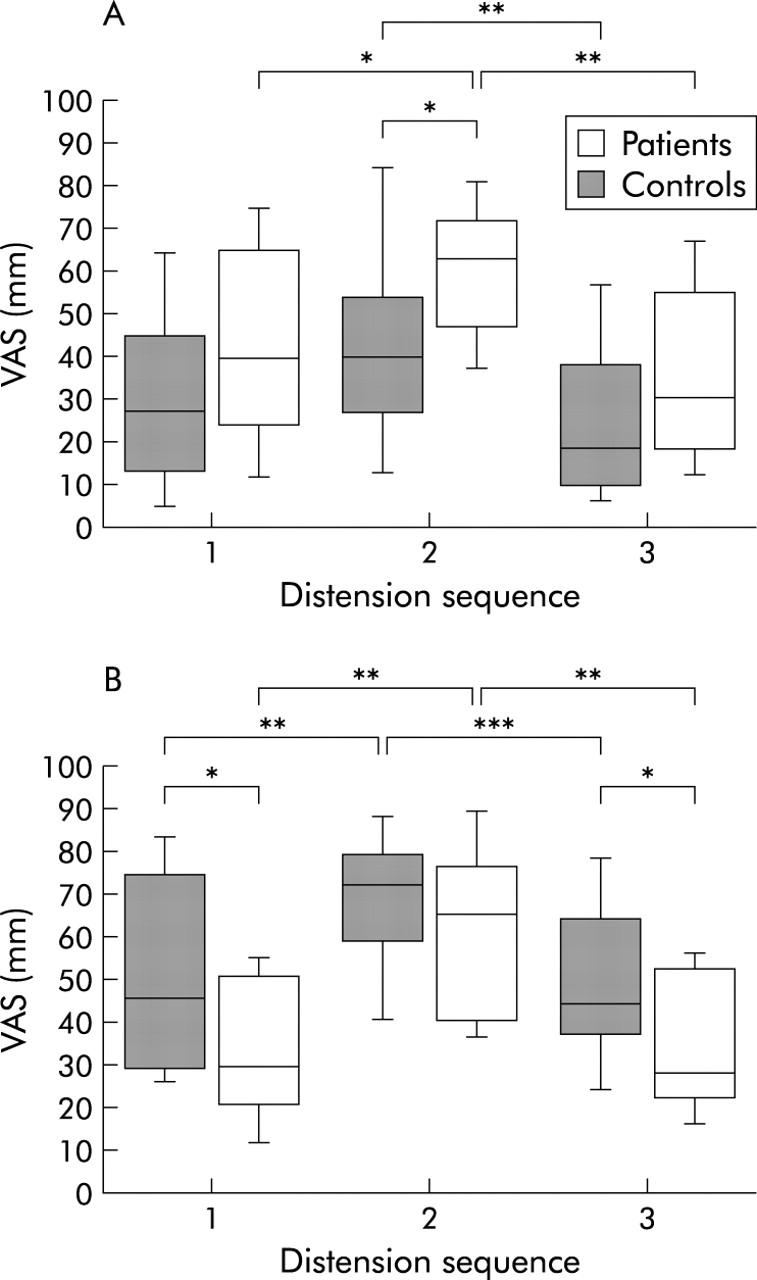

Stress and arousal

Only data from series I are shown. In both groups, heart rate was increased during stress compared with resting periods (p<0.001), and was not affected by distensions. There were no significant group differences in heart rate (fig 3 ▶). The Stroop test and the mental arithmetic test increased the ratings of perceived stress compared with before and after stress in both patients (p = 0.02; p = 0.003) and controls (p = 0.07; p = 0.002). During all three distension sequences, patients reported higher ratings of stress than controls (p = 0.1; p = 0.02; p = 0.08) (fig 4A ▶). Higher ratings of arousal were also reported during the stress period compared with before and after by both patients (p = 0.003; p = 0.001) and controls (p = 0.005; p = 0.0004). Patients demonstrated lower ratings of arousal than controls both before and after stress (p = 0.03; p = 0.04) (fig 4B ▶).

Figure 3.

Mean heart rate during the distension sequences (1, 2, and 3) and the resting periods in between, in patients and controls. An increase was observed in both groups during stress. ***p<0.001.

Figure 4.

Visual analogue scale (VAS) ratings of perceived stress (A) and arousal (B) (median (interquartile range (IQR)) during the separate distension sequences in series I experiments in patients and controls. Both groups reported higher ratings of both stress and arousal during the stress period. Compared with controls, patients demonstrated higher ratings for stress but lower for arousal. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

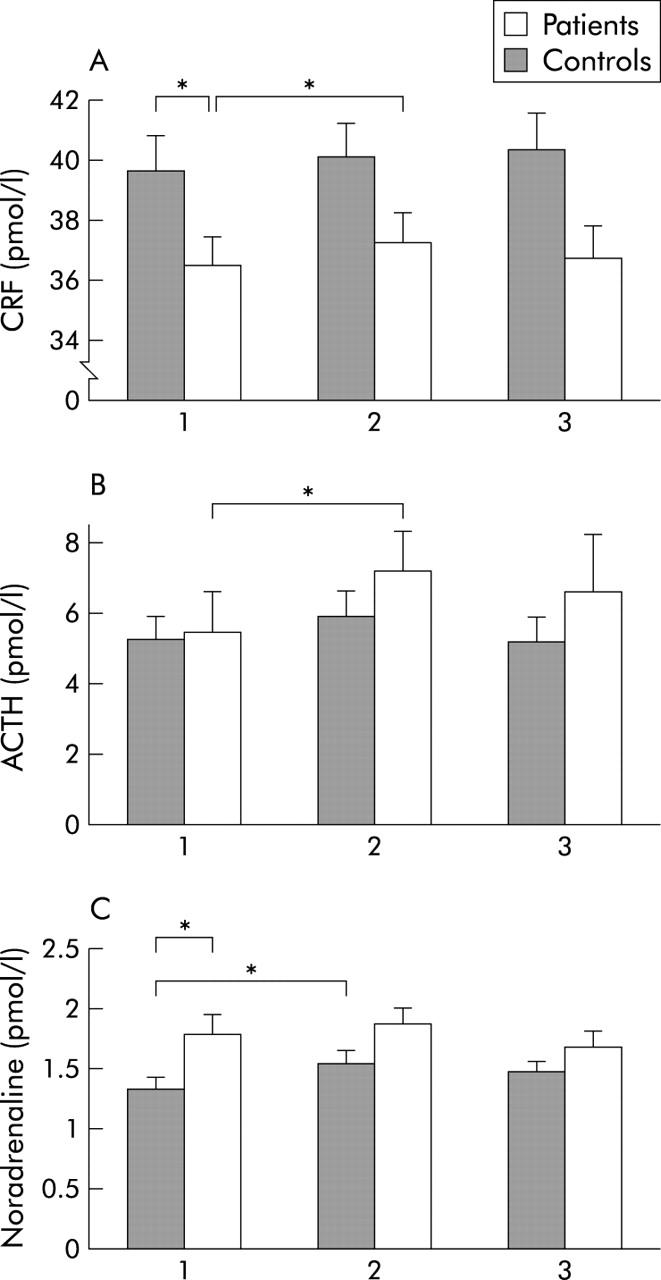

Blood samples

Blood samples from series I and II B were analysed together. Basal levels of CRF in plasma were lower in patients than in controls (p = 0.04). Patients but not controls demonstrated a significant rise in CRF during stress (p = 0.01) (fig 5A ▶). Similarly, IBS patients but not controls demonstrated a marked rise in ACTH during stress (p = 0.03) (fig 5B ▶). In healthy subjects, but not in patients, increased levels of adrenaline (0.11 (0.01) v 0.14 (0.02) pmol/l; p = 0.01) and noradrenaline (p = 0.008) (fig 5C ▶) were observed in response to stress. However, patients had higher basal levels of noradrenaline compared with controls (p = 0.01) (fig 5C ▶). No significant rise or group difference was observed in cortisol levels in response to stress (data not shown). Similar results were obtained when analysing samples from series I and II B separately (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Levels of corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) (A), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (B), and noradrenaline (C) (mean (SEM)) at baseline (1), after stress (2), and at the end of the experiment (3) in patients and controls. Patients had lower basal levels of CRF but showed a stress provoked increase in both CRF and ACTH that was not seen in controls. Basal levels of noradrenaline were higher in patients, but controls and not patients demonstrated increased levels in response to stress. *p<0.05.

In series II A and C, patients demonstrated lower baseline levels of CRF (pmol/l) compared with controls (35.9 (1.0) v 44.9 (2.4) (p = 0.005) and 35.9 (2.1) v 45.7 (2.7) (p = 0.01)). Stress without a distension sequence (II C) caused a rise in CRF in patients (35.9 (2.1) v 38.4 (2.4); p = 0.04) but not in controls. No changes in levels of CRF were seen during distensions without stress (II A). No significant group differences were observed for levels of ACTH, noradrenaline, adrenaline, or cortisol (data not shown).

HAD and STAI

IBS patients had higher scores on HAD than healthy subjects for both anxiety (7 (7–10) v 5 (3–6); p<0.001) and depression (4 (2–7) v 1(1–2); p<0.001). STAI showed differences between patients and controls for both state anxiety (36 (32–43) v 30 (25–34); p<0.01) and trait anxiety (41 (34–49) v 30 (26–34); p<0.001). Using cut off levels (⩾11) for the HAD scale,27 only three and two patients suffered from clinically significant anxiety and depression, respectively. No strong correlations were found between these results and sensory thresholds, VAS scores, or levels of neuropeptides (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that acute mental stress modulates rectal perception in both healthy controls and IBS patients. In controls, sensory thresholds for rectal balloon distensions were higher during stress. However, in patients, thresholds did not change during stress but were decreased after stress. Thus patients showed altered visceral perception in response to acute mental stress compared with healthy subjects. We also found that IBS patients had changes in their neuroendocrine stress response.

Previous studies on stress and visceral perception show contradictory results. Erckenbrecht11 showed that mental stress induces visceral hypersensitivity in healthy volunteers. The opposite was observed with physical stress, which induced visceral hyposensitivity. However, a preliminary study in healthy subjects showed that rectal sensitivity was decreased in response to both psychological and physiological stress.9 Ford and colleagues7 found that stress increased and relaxation decreased perceived intensity of sensations in the colon in healthy volunteers. Stress has been found to both increase8 and decrease10 rectal sensitivity in patients whereas it seemed to have no effect on healthy controls.

Different methodological approaches in these studies must however be taken into account when interpreting these and our results. Differences may be explained in part by differing techniques for assessment of sensory thresholds. Furthermore, results obtained in the rectum cannot be transposed to the colon. In stress response studies, the nature of the challenge may influence both the quantity and quality of the response. In rats, acute and chronic stress has been shown to affect visceral sensitivity differently.31 The stress period in the present study might have been too short to induce a sufficient emotional stress response. However, as we observed increased heart rate, greater experienced stress and arousal, as well as elevated stress parameters in blood, we believe that our method successfully provoked stress. This extends beyond previous studies in which these parameters were not fully evaluated.

Depending on the stress provoking technique used, various degrees of distraction will also occur. Distraction during visceral distensions seems to decrease visceral sensitivity in healthy subjects6,10 but not in IBS patients.10 Inconsistent results in the stress studies mentioned above may have occurred because stress coexisted with distraction in varying amounts. In our study, the acute mental challenge decreased rectal sensitivity in healthy controls. However, we did not observe any effects of stress on sensory thresholds when the stress stimuli were administered immediately before the second distension sequences (II B). This indicates that the decreased rectal sensitivity in healthy subjects during the acute mental stress was probably an effect of distraction, affecting descending inhibitory pathways.32

In IBS patients, rectal sensitivity was unaltered during stress (that is, they could not suppress or “turn off” signals from their bowel during the mental challenge). In accordance with this finding, IBS patients are presumed to have selective attention or hypervigilance regarding gastrointestinal sensations.33 There could also be differences in cognitive processing of incoming stimuli at the brain level34,35 as the altered perception of stress and arousal in patients compared with controls during the stressful task might indicate. Also, various afferent or descending pathways can modulate sensory perception and some data suggest that IBS patients have inadequate function in the descending analgesic system.36 Moreover, peripheral factors, such as mast cells, could also be involved by sensitising visceral afferent terminals.37

Patients showed increased sensitivity during the last series of distensions in the sessions where they underwent stress and three sets of distensions (I). This could be due to perceptual response bias caused by learning and anticipation of painful distensions.38 However, repeated distensions without stress (II A) did not induce hypersensitivity. Nor was there any effect on sensitivity in the experiments with stress and only two distension sequences (II C). This may indicate that stress alone did not induce hypersensitivity, but in combination with repeated distensions it did, indicating a late stress response aggravated by repeated distensions.39

Central release of CRF and related molecules are believed to play an important role in the stress response.16 Lembo and colleagues18 found increased rectal sensitivity after intravenous administration of CRF in healthy subjects. However, CRF administered either peripherally or centrally has been reported to induce somatic analgesia.40 Interestingly, in the present study, basal levels of CRF were lower in patients than in controls. IBS patients are proposed to have elevated levels of CRF,13 as seen in post-traumatic stress disorder.41 High peripheral levels of CRF might be a characteristic of patients exposed to severe stress and/or with mood and anxiety disorders.42 In rats, moderate chronic stress has been shown to result in low CRF levels.43 Most patients in our study did not fulfil criteria for depression or anxiety, as judged by questionnaires, or clinically, which might explain low CRF levels. It is also possible that peripheral levels measured in our study are not representative of central levels. Finally, one cannot exclude methodological issues such as different sample handling and different antibody specificity as a reasonable explanation for the variation in published results. However, it is unlikely that this explains group differences.44

We observed a significant rise in plasma CRF in response to stress in patients but not in controls. In agreement with this, patients, as opposed to controls, reacted with higher levels of ACTH. IBS patients have previously been proposed to have an exaggerated brain-gut response to CRF.17 The present findings, with a marked ACTH increase despite moderate CRF levels, suggest that such exacerbation exists in patients at the hypothalamic-hypopituitary level also. However, patients did exhibit a normal cortisol response during stress suggesting adaptation or desensitisation of the adrenal cortex.17,42 In accordance with other investigators we also found that basal levels of noradrenaline were higher in patients than in controls,23,45 indicating enhanced activity of the sympathetic nervous system. Increased sympathetic activity is known to modulate both visceral tone and perception.46,47 However, IBS patients, as opposed to controls, did not react with increased adrenaline or noradrenaline levels during stress, again perhaps due to adrenal adaptation. We do not have enough evidence in the present study to suggest a direct cause-effect relationship between the neuroendocrine and perceptual responses to stress as no clear correlations were found between these responses. However, a more complex relationship cannot be excluded as several other factors might be involved in the symptomatic response to stress, such as motility changes16 and psychological factors.41,42

In the present study, which can be viewed as an exploratory study, several statistical comparisons were performed. We did not correct for multiple comparisons formally but exact p values were given as far as possible, making it possible to assess the strength of the various findings. Moreover, the findings found were consistent and robust enough to exclude chance findings.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that acute mental stress modifies visceral perception in both healthy controls and IBS patients. This was possibly due to both a direct effect of stress as well as distraction due to the mental task. However, compared with healthy subjects, when exposed to mental stress, patients exhibited both altered visceral perceptual and an exaggerated neuroendocrine response. This may explain some of the stress related symptoms often observed in IBS.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council (grant 13409) and by the Faculty of Medicine, University of Göteborg.

Abbreviations

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone

CRF, corticotropin releasing factor

HAD scale, hospital anxiety and depression scale

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome

IBS-D, diarrhoea predominant irritable bowel syndrome

IBS-C, constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome

IBS-A, alternating type IBS

IQR, interquartile range

STAI, Spielberger state trait anxiety inventory

VAS, visual analogue scale

REFERENCES

- 1.Agreus L , Svärdsudd K, Nyren O, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia in the general population: overlap and lack of stability over time. Gastroenterology 1995;109:671–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitehead W E, Crowell M D, Robinson J C, et al. Effects of stressful life events on bowel symptoms: subjects with irritable bowel syndrome compared with subjects without bowel dysfunction. Gut 1992;33:825–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enck P , Merlin V, Erckenbrecht J F, et al. Stress effects on gastrointestinal transit in the rat. Gut 1989;30:455–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukudo S , Suzuki J. Colonic motility, autonomic function, and gastrointestinal hormones under psychological stress on irritable bowel syndrome. Tohoku J Exp Med 1987;151:373–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welgan P , Meshkinpour H, Beeler M. Effect of anger on colon motor and myoelectric activity in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1988;94 (Pt 1) :1150–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Accarino A M, Azpiroz F, Malagelada J R. Attention and distraction: effects on gut perception. Gastroenterology 1997;113:415–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford M J, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister A R, et al. Psychosensory modulation of colonic sensation in the human transverse and sigmoid colon. Gastroenterology 1995;109:1772–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickhaus B , Mayer E A, Firooz N, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome patients show enhanced modulation of visceral perception by auditory stress. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Métivier S , Delvaux M, Louvel D, et al. Influence of stress on sensory thresholds to rectal distension in healthy volunteers. Gastroenterology 1996;110:A717. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mönnikes H , Heymann-Mönnikes I, Arnold R. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) have alterations in the CNS-modulation of visceral afferent perception. Gut 1995;37:A168. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erckenbrecht J F. Noise and intestinal motor alterations. In: Bueno L, Collins SM, Junien JL, eds. Stress and digestive motility. London: John Libbey Eurotext, 1989:93–6.

- 12.Houghton L A, Prior A, Whorwell P J. Effect of acute stress on anorectal physiology in normal healthy volunteers. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1994;6:389–92. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayer E A. The neurobiology of stress and gastrointestinal disease. Gut 2000;47:861–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aggarwal A , Cutts T F, Abell T L, et al. Predominant symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome correlate with specific autonomic nervous system abnormalities. Gastroenterology 1994;106:945–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munakata J , Mayer E A, Chang L, et al. Autonomic and neuroendocrine responses to recto-sigmoid stimulation. Gastroenterology 1998;114:A808. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tache Y , Martinez V, Million M, et al. Corticotropin-releasing factor and the brain-gut motor response to stress. Can J Gastroenterol 1999;13 (suppl A) :18A–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukudo S , Nomura T, Hongo M. Impact of corticotropin-releasing hormone on gastrointestinal motility and adrenocorticotropic hormone in normal controls and patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 1998;42:845–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lembo T , Plourde V, Shui Z, et al. Effects of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) on rectal afferent nerves in humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil 1996;8:9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayer E A, Naliboff B D, Chang L, et al. V. Stress and irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2001;280:G519–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson W G, Longstreth G F, Drossman D A, et al. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut 1999;45 (suppl 2) :II43–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen A R, Rohwer W Djr. The Stroop color-word test: a review. Acta Psychol 1966;25:36–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narducci F , Snape W Jjr, Battle W M.et al. Increased colonic motility during exposure to a stressful situation. Dig Dis Sci 1985;30:40–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine B S, Jarrett M, Cain K C, et al. Psychophysiological response to a laboratory challenge in women with and without diagnosed irritable bowel syndrome. Res Nurs Health 1997;20:431–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mackay C , Cox T, Burrows G, et al. An inventory for the measurement of self-reported stress and arousal. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1978;17:283–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox T , Mackay C. The measurement of self-reported stress and arousal. Br J Psychol 1985;76 (Pt 2) :183–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mertz H , Naliboff B, Munakata J, et al. Altered rectal perception is a biological marker of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1995;109:40–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zigmond A S, Snaith R P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spielberger C . Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory (form Y). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1983.

- 29.Ekman R , Servenius B, Castro M G, et al. Biosynthesis of corticotropin-releasing hormone in human T-lymphocytes. J Neuroimmunol 1993;44:7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holly J M, Makin H L. The estimation of catecholamines in human plasma. Anal Biochem 1983;128:257–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bradesi S , Eutamene H, Garcia-Villar R, et al. Acute and chronic stress differently affect visceral sensitivity to rectal distension in female rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2002;14:75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayer E A, Gebhart G F. Basic and clinical aspects of visceral hyperalgesia. Gastroenterology 1994;107:271–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naliboff B D, Munakata J, Fullerton S, et al. Evidence for two distinct perceptual alterations in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 1997;41:505–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverman D H, Munakata J A, Ennes H, et al. Regional cerebral activity in normal and pathological perception of visceral pain. Gastroenterology 1997;112:64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mertz H , Morgan V, Tanner G, et al. Regional cerebral activation in irritable bowel syndrome and control subjects with painful and nonpainful rectal distention. Gastroenterology 2000;118:842–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lembo T , Naliboff B D, Matin K, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome patients show altered sensitivity to exogenous opioids. Pain 2000;87:137–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gue M , Del Rio-Lacheze C, Eutamene H, et al. Stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity to rectal distension in rats: role of CRF and mast cells. Neurogastroenterol Motil 1997;9:271–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whitehead W E, Delvaux M. Standardization of barostat procedures for testing smooth muscle tone and sensory thresholds in the gastrointestinal tract. The Working Team of Glaxo-Wellcome Research, UK. Dig Dis Sci 1997;42:223–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munakata J , Naliboff B, Harraf F, et al. Repetitive sigmoid stimulation induces rectal hyperalgesia in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1997;112:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hargreaves K M, Mueller G P, Dubner R, et al. Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) produces analgesia in humans and rats. Brain Res 1987;422:154–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bremner J D, Licinio J, Darnell A, et al. Elevated CSF corticotropin-releasing factor concentrations in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1997;154:624–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heim C , Newport D J, Heit S, et al. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. JAMA 2000;284:592–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plotsky P M, Meaney M J. Early, postnatal experience alters hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) mRNA, median eminence CRF content and stress-induced release in adult rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1993;18:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simrén M , Stotzer P-O, Sjövall H, et al. Abnormal levels of neuropeptide Y and YY in the colon in the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;15:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heitkemper M , Jarrett M, Cain K, et al. Increased urine catecholamines and cortisol in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:906–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bharucha A E, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister A R, et al. Adrenergic modulation of human colonic motor and sensory function. Am J Physiol 1997;273 (Pt 1) :G997–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iovino P , Azpiroz F, Domingo E, et al. The sympathetic nervous system modulates perception and reflex responses to gut distention in humans. Gastroenterology 1995;108:680–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]