Abstract

Background and aim: Gastric intestinal metaplasia (IM) is generally considered to be a precancerous lesion in the gastric carcinogenesis cascade. This study identified the risk factors associated with progression of IM in a randomised control study.

Subjects and methods: A total of 587 Helicobacter pylori infected subjects were randomised to receive a one week course of anti-Helicobacter therapy (omeprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin (OAC)) or placebo. Subjects underwent endoscopy with biopsy at baseline and at five years. Severity of IM was graded according to the updated Sydney classification and progression was defined as worsening of IM scores at five years in either the antrum or corpus, or development of neoplasia. Backward stepwise multiple logistic regression was used to identify independent risk factors associated with IM progression.

Results: Of 435 subjects (220 in the OAC and 215 in the placebo group) available for analysis, 10 developed gastric cancer and three had dysplasia. Overall progression of IM was noted in 52.9% of subjects. Univariate analysis showed that persistent H pylori infection, age >45 years, male subjects, alcohol use, and drinking water from a well were significantly associated with IM progression. Duodenal ulcer and OAC treatment were associated with a reduced risk of histological progression. Progression of IM was more frequent in those with more extensive and more severe IM at baseline. With multiple logistic regression, duodenal ulcer (odds ratio (OR) 0.23 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.09–0.58)) was found to be an independent protective factor against IM progression. Conversely, persistent H pylori infection (OR 2.13 (95% CI 1.41–3.24)), age >45 years (OR 1.92 (95% CI 1.18–3.11)), alcohol use (OR 1.67 (95% CI 1.07–2.62)), and drinking water from a well (OR 1.74 (95% CI 1.13–2.67)) were independent risk factors associated with IM progression.

Conclusion: Eradication of H pylori is protective against progression of premalignant gastric lesions.

Keywords: intestinal metaplasia, randomised trial, Helicobacter pylori, gastric cancer, prevention

Gastric cancer is the second leading cause of cancer related mortality worldwide. Evidence shows that the pathogenesis of gastric cancer, particularly the intestinal-type, involves multistep progression from gastritis to glandular atrophy (GA), intestinal metaplasia (IM), dysplasia, and ultimately to cancer.1 The gastric carcinogenesis cascade is generally considered to be triggered by Helicobacter pylori infection. Meta-analysis shows that infection with H pylori confers a 2–3-fold increase in the risk of gastric cancer development.2,3 In a prospective study from Japan, 2.9% of infected subjects developed gastric cancer over a mean follow up period of 7.8 years.4 In contrast, none of the uninfected individuals developed cancer. Moreover, H pylori infected subjects with IM were found to have a 6.4-fold increased risk of gastric cancer.

Despite a strong causal link between H pylori infection and gastric cancer, data showing that treatment of H pylori infection could actually prevent cancer are lacking. This is largely due to the long lead time in gastric cancer development. In order to assess the potential benefits of H pylori eradication, most studies are designed to examine regression of precancerous changes, such as IM and GA of the stomach, as surrogate end points of treatment success. None the less, there are conflicting data in the literature due to differences in study populations and design.5–10 Some studies also lack a suitable control arm and adjustment for confounding factors.

In the placebo controlled randomised study from Colombian reported by Correa and colleagues,9 patients were randomised to receive eight different treatments, including vitamin supplements and anti-Helicobacter therapy alone or in combination, compared with placebo for up to six years. After successful eradication of H pylori, there was modest regression of IM compared with placebo (15% v 6%). Interestingly, supplementation of β-carotene or ascorbic acid resulted in a similar degree of improvement in IM (20% and 19%). None the less, combinations of anti-H pylori therapy and vitamins conferred no additional benefit on gastric histology. IM progression rates were similar in all treatment groups and the actual benefit of anti-Helicobacter treatment was questionable.11 One of the reasons for this conflicting result may be the lack of statistical power of this study that involved multiple treatment arms. Additionally, the results may be confounded by other environmental and demographic factors that contribute to progression of premalignant gastric lesions.

We have recently completed a five year prospective randomised control study in Yantai county of Shandong Province where gastric cancer incidence is among the highest in China.10,12 In this study, H pylori infected subjects were randomised to receive either anti-Helicobacter therapy or placebo. The results of the one year and five year follow up have been reported previously.10,12 In summary, we concluded that there was a dramatic improvement in acute and chronic gastritis in the treated (omeprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin) group. Five years after H pylori eradication, progression of gastric IM was retarded in the eradication group. However, a considerable proportion of subjects in both treatment arms still had histological progression of IM. It thus appears that progression of gastric IM may be influenced by factors in addition to H pylori eradication. In fact, previous studies showed that factors such as smoking,13 age of patients,10 and pattern or severity of gastritis4,14 may influence the progression of precancerous gastric lesions. Studies that fail to adjust for these factors may undermine the real benefits of H pylori eradication. In the present study, we attempted to identify independent risk factors associated with progression of gastric IM in this prospective study. We also aimed to identify a subgroup of high risk subjects that might warrant more intensive surveillance.

METHODS

Study design and study population

Details of subject characteristics and the results of the one year and five year follow up study were reported previously.10,12 Briefly, volunteers residing in the Yantai county of Shandong Province were invited for screening endoscopy in 1996. This is a rural region with a very high gastric cancer incidence (50 per 100 000 population). The residents are predominantly comprised of farmers of lower socioeconomic class. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and the study protocol was approved by the clinical research ethics committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. All participants were interviewed on their medical and family histories, followed by a brief physical examination. A structured questionnaire elicited information on demographic data, smoking habits (active smoker, non-smoker, or ex-smoker), alcohol use (active drinker, non-drinker, or ex-drinker) and source of drinking water (tap or well).

During gastroscopy, the presence of peptic ulcer or tumour was noted. In all subjects, three antral biopsies were taken from the greater and lesser curvatures 2–3 cm from the pylorus, and two corpus biopsies were obtained from the lesser curvature and the greater curvature at the mid corpus. One antral biopsy was used for determination of H pylori status using the rapid urease test (CLOtest; Ballard, Draper, Utah, USA) whereas the remaining gastric biopsies were used for histological examination. Samples from the antrum and corpus were stored in separate bottles that were readily identifiable.

H pylori infection was diagnosed when both the rapid urease test and histology were positive. H pylori positive subjects were then randomised to receive either a one week course of anti-Helicobacter therapy (OAC: omeprazole 20 mg, amoxicillin 1 g, and clarithromycin 500 mg, all given twice daily) or placebo. Medications had identical appearances. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, allergy to the prescribed medication, suspected gastric malignancy, prior gastric surgery, concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and comorbid illnesses that might increase the risk of complications from gastroscopy.

Follow up gastroscopy was arranged at one year and five year intervals after randomisation. Gastric biopsies were taken from the same sites as described above for both endoscopies. The rapid urease test was repeated to monitor H pylori status. Subjects who defaulted follow up were traced by the local village doctors to document their outcome, particularly in the development of gastric cancer. Hospital records and death certificates were retrieved to document the nature of any illnesses and causes of death in those who underwent surgery or died within the five year study period. The cagA status of these individuals was determined by serological response against CagA on entry to the study, as described previously.10

Histology

Gastric biopsy specimens were fixed in buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin and modified Giemsa techniques. All histological assessment was made by a single experienced pathologist (KFT). Slides were coded in a random manner such that the pathologist was blinded to the identity of subjects, treatment assignment, and year at which biopsies were obtained. Histological sections of the antrum and corpus tissue were graded for H pylori density, intensity of acute (polymorphonuclear cells) infiltrates, intensity of chronic (mononuclear cells) infiltrates, GA, and IM, as stipulated by the updated Sydney system (Houston).15 All parameters were graded as none (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or marked (3). IM was recognised morphologically by the presence of goblet cells, absorptive cells, and cells resembling colonocytes. Dysplasia (or intraepithelial neoplasia) was defined as stipulated in the Padova international classification.16 Briefly, diagnosis of dysplasia was restricted to cases showing both altered glandular architecture and abnormalities in cytology and differentiation but lacking any infiltrating features. Carcinoma was diagnosed when tumours invaded the lamina propria or were through the muscularis mucosae.17

To determine intraobserver variation in histological assessments over the five year study period, the same pathologist (KFT) was asked to re-score 30 randomly selected cases taken from various follow up endoscopies. Consistent results were obtained in acute inflammation (86%), chronic inflammation (96%), GA (92%), and IM (96%). Moreover, interobserver variability was assessed by asking a second pathologist to score gastric biopsies from 224 randomly selected cases. Kappa statistics were used to compute the consistency of scoring between the two pathologists. The kappa value for antral IM was 0.898 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.87–0.97) and for body IM 0.84 (95% CI 0.77–0.91).

Statistical analysis

All subjects included in this analysis either had completed the two endoscopic examinations at baseline and at five years, or had developed gastric cancer within the five year follow up period. Histological scores of IM at entry and at five years were compared. Progression of IM was defined as a higher score at five years compared with baseline in either the antrum or corpus. Moreover, subjects who had developed gastric dysplasia or cancer were regarded as having histological progression.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 11.5; SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Possible baseline covariables associated with progression of IM were analysed by univariate analysis. These included age (>45 years v ⩽45 years), sex (male v female), tobacco use (smokes v non-smokers+ex-smokers), alcohol use (drinkers v non-drinkers+ex-drinkers), source of drinking water (well v tap), and presence of peptic ulcer. The effect of H pylori eradication was assessed in three separate analyses: (1) the odds ratio (OR) for progression in those who received OAC treatment versus placebo, (2) the OR for progression in those who received OAC with confirmed H pylori clearance versus those who received placebo with persistent infection, and (3) those with persistent H pylori infection versus those who remained negative for H pylori infection at five years, regardless of treatment allocation. Possible associations between the baseline distribution of IM and severity of IM in the antrum and risk of IM progression were also assessed. ORs (with 95% CI) are presented. Factors with a trend towards affecting progression of histology (p<0.10) were included in the backward stepwise multiple logistic regression model to identify significant predictors associated with IM progression. All p values were two sided and statistical significance was taken at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Patients

Five hundred and eighty seven H pylori infected subjects were randomised in this study. A total of 295 received a one week course of OAC whereas 292 received placebo. Seventy five patients in the OAC group and 77 in the placebo group were lost to follow up. Data from 435 subjects (220 in the OAC group and 215 in the placebo group) were available for the five year analysis. There were 208 males and 227 females with a mean age of 52.0 (8.1) years.

Clearance of H pylori infection was confirmed at five years in 164 (74.5%) subjects who had received OAC whereas 20 (9.3%) subjects in the placebo group were negative for H pylori by histology at five years. Twenty six (6.0%) subjects were diagnosed as having duodenal ulcer and 16 (3.7%) gastric ulcer. Ten (2.3%) subjects developed invasive gastric cancers during the five year follow up period. Four cancers were in the OAC group whereas the remaining six cancers were in the placebo group. As not all cancer patients had undergone surgery, data on pathological staging and final H pylori status were incomplete. However, all 10 cancer patients died from gastric cancer, suggesting that they were of advanced staging. Additionally, three subjects in the placebo group were noted to have dysplasia during the five year follow up endoscopy.

Changes in gastric histology of each individual over the five year follow up period are summarised in table 1 ▶. Both forward and backward movements from one stage to the other were frequently noted during the follow up examination. Eight patients with IM at baseline developed gastric cancer. Conversely, IM was no longer detected in 26 patients with baseline IM. Progression or deterioration of gastric IM was also frequently noted during the five years of follow up. Of the 435 subjects, 230 (52.9%) had progression of gastric IM which included 13 subjects with gastric cancer or dysplasia.

Table 1.

Frequency of gastric pathology changes after five years of follow up according to baseline pathology results

| 5 year follow up pathology | ||||||

| Normal (n = 38) | Inflammation (n = 98) | GA (n = 13) | IM (n = 273) | Dys (n = 3) | Cancer (n = 10) | |

| Baseline pathology* | ||||||

| Inflammation (n = 237) | 29 | 82 | 12 | 111 | 1 | 2 |

| GA (n = 4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| IM (n = 194) | 9 | 16 | 1 | 158 | 2 | 8 |

Dys, dysplasia; GA, glandular atrophy; IM, intestinal metaplasia; Inflammation, active and/or chronic inflammation only.

*As all subjects were infected with Helicobacter pylori, there was no normal histology at baseline.

Baseline demographic and histological progression

Table 2 ▶ summarises the results of the univariate analysis of baseline demographic and clinical data in the risk of IM progression. Univariate analysis showed that male subjects had a higher risk of progression of IM than female subjects (OR 1.51 (95% CI 1.03–2.20); p = 0.034). The risk of progression was also higher in subjects aged >45 years (OR 1.95 (95% CI 1.24–3.07); p = 0.004). Alcohol users or those who obtained drinking water from a well had significantly higher risks of IM progression. Tobacco smokers tended to have a higher risk of IM progression compared with non-smokers and ex-smokers but the difference did not reach statistical significance (OR 1.49 (95% CI 0.99–2.25); p = 0.06). In contrast, subjects who had duodenal ulcers on first endoscopy had a reduced risk of progression of IM (OR 0.28 (95% CI 0.12–0.67)) but the presence of gastric ulcer did not have any effect on IM progression. Family history of gastric cancer or the presence of anti-CagA antibody were not associated with IM progression.

Table 2.

Odds ratio (OR with 95% confidence interval (CI)) for progression of intestinal metaplasia (IM) according to baseline variables: univariate analysis

| IM deterioration (n = 230) | No IM deterioration (n = 205) | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age >45 y | 189 (82.2%) | 144 (70.2%) | 1.95 (1.24–3.07) | 0.004 |

| Male | 121 (52.6%) | 87 (42.4%) | 1.51 (1.03–2.20) | 0.034 |

| Alcohol use | 80 (34.8%) | 51 (24.9%) | 1.61 (1.06–2.44) | 0.025 |

| Smoking | 80 (34.8%) | 54 (26.3%) | 1.49 (0.99–2.25) | 0.059 |

| Drinking water from well | 94 (40.9%) | 64 (31.2%) | 1.52 (1.03–2.46) | 0.037 |

| Family history of stomach cancer | 28 (12.2%) | 18 (8.8%) | 1.44 (0.77–2.69) | 0.25 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 6 (2.6%) | 20 (9.8%) | 0.28 (0.12–0.67) | 0.004 |

| Gastric ulcer | 10 (4.3%) | 6 (2.9%) | 1.52 (0.54–4.3) | 0.43 |

| Anti-CagA antibody | 150 (65.2%) | 142 (69.3%) | 1.14 (0.74–1.76) | 0.54 |

Baseline histology and histological progression

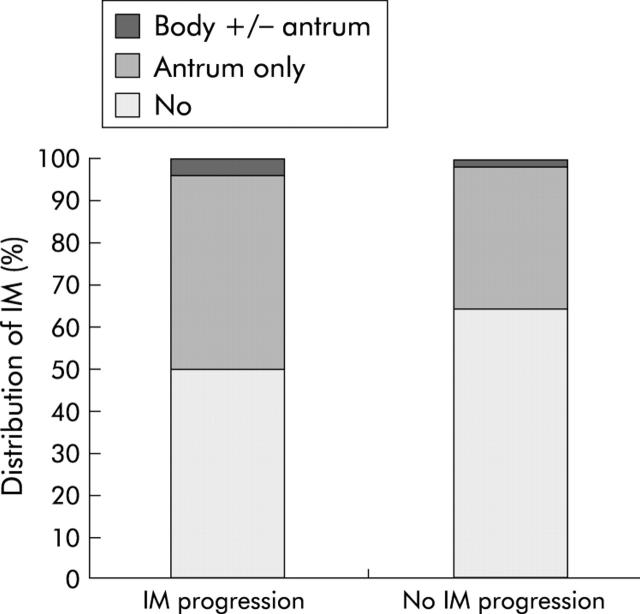

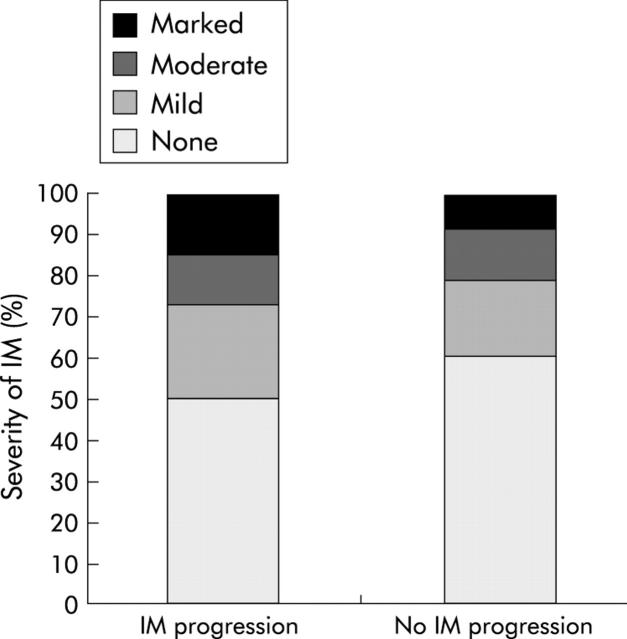

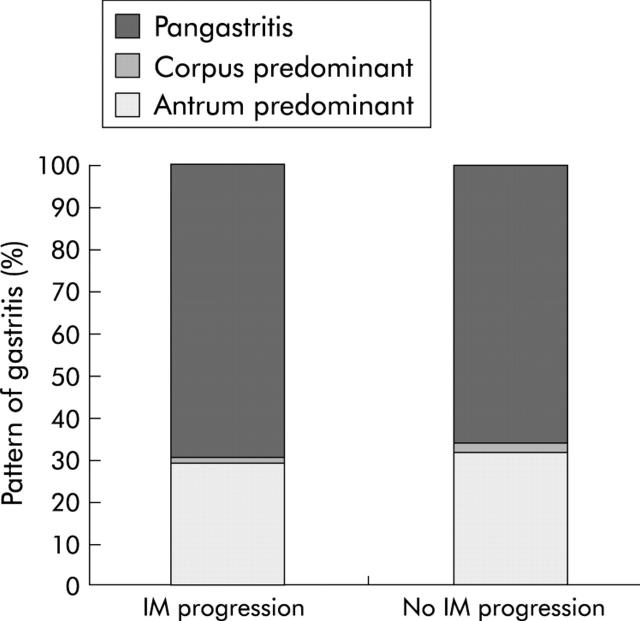

We assessed the severity and patterns of gastric histology at baseline and its association with the risk of IM progression. As shown in fig 1 ▶, there was a significant difference in the distribution patterns of IM at baseline between those with and without progression (p = 0.01). Subjects with IM progression tended to have more severe IM in the antrum at baseline (p = 0.08, fig 2 ▶). In contrast, there was no association between the pattern of gastritis and IM progression (fig 3 ▶). The risk of progression was comparable in those with antral predominant gastritis, corpus predominant, or pangastritis (OR 0.89 (95% CI 0.57–1.38)).

Figure 1.

Baseline distribution of intestinal metaplasia (IM) in subjects with IM progression. p<0.01.

Figure 2.

Severity of antral intestinal metaplasia (IM) at baseline and progression of gastric IM. p = 0.084.

Figure 3.

Pattern of gastritis at baseline and progression of gastric intestinal metaplasia (IM). Antrum versus corpus/pangastritis, p = 0.69.

Effect of H pylori eradication on histological progression

Table 3 ▶ summarises the risk of IM progression with regard to treatment allocation and final H pylori statuses. Eradication of H pylori infection was significantly associated with reduction in the risk of IM progression. Patients assigned to receive OAC had a significantly lower risk of IM progression compared with those who received placebo (OR for histological progression 0.63 (95% CI 0.43–0.93); p = 0.018)). Comparing those in the OAC group with H pylori eradicated with those with persistent H pylori infection in the placebo group, the OR of histological progression was further reduced to 0.48 (95% CI 0.32–0.74); p<0.001). Also, the risk of IM progression was significantly higher in those with persistent H pylori infection at five years, regardless of treatment allocation (OR 2.14 (95% CI 1.45–3.16); p<0.001).

Table 3.

Odds ratio (OR with 95% confidence interval (CI)) for progression of intestinal metaplasia (IM) according to Helicobacter pylori treatment and/or final H pylori status

| IM deterioration | No IM deterioration | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| OAC group | 104 (45.2%) | 116 (56.6%) | 0.63 (0.43–0.93) | 0.018 |

| Placebo group | 126 (54.8%) | 89 (43.4%) | 1.0 (referent) | |

| OAC+HP−ve | 68 (37.6%) | 96 (55.5%) | 0.48 (0.32–0.74) | <0.001 |

| Placebo+Hp+ve | 113 (62.4%) | 77 (44.5%) | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Hp+ve at 5 y | 146 (65.8%) | 97 (47.3%) | 2.14 (1.45–3.16) | <0.001 |

| Hp−ve at 5 y | 76 (34.2%) | 108 (52.7%) | 1.0 (referent) |

Hp+ve, H pylori infected; Hp−ve, H pylori negative.

OAC, omeprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin.

Multivariate logistic regression

Table 4 ▶ summarises the risks of IM progression with the following factors entered into the logistic regression model: age, sex, smoking, alcohol, source of drinking water, presence of duodenal ulcer, severity of baseline antral IM, treatment allocation, and final H pylori status. After stepwise logistic regression, five factors remained statistically significant: subject age >45 years, alcohol use, source of drinking water, presence of duodenal ulcer, and final H pylori status (table 4 ▶).

Table 4.

Factors predicting intestinal metaplasia (IM) progression: multivariate logistic regression

| Factor | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Persistent Hp+e | 2.13 (1.41–3.23) | <0.001 |

| Age >45 y | 1.92 (1.18–3.11) | 0.009 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 0.25 (0.09–0.66) | 0.005 |

| Alcohol use | 1.67 (1.07–2.62) | 0.03 |

| Drinking water from well | 1.74 (1.13–2.67) | 0.01 |

Hp+ve, H pylori infected.

Values are odds ratios with 95% confidence interval (OR (95% CI)).

In summary, subjects who remained positive for H pylori at five years had a significantly higher risk of IM progression than those with successful eradication (adjusted OR 2.13 (95% CI 1.41–3.24); p<0.001). Duodenal ulcer patients were less likely to have IM progression (adjusted OR 0.25 (95% CI 0.09–0.66); p = 0.005). IM progression was more frequently noted in subjects aged >45 years (adjusted OR 1.92 (95% CI 1.18–3.11); p = 0.009). The rate of progression was highest among subjects >45 years with persistent H pylori infection (62.8%) and lowest in younger subjects with successful H pylori eradication (28.6%) (fig 4 ▶). Environmental factors, including alcohol use and drinking well water, were also independent risk factors for IM progression.

Figure 4.

Rate of progression of gastric intestinal metaplasia (IM) according to final Helicobacter pylori (Hp) status after age stratification.

DISCUSSION

In this five year prospective study, 53% of subjects were noted to have progression of gastric IM. Moreover, it was noted that 2.3% of H pylori infected subjects developed gastric cancer over the five year follow up period. Thus the mean annual risk of gastric cancer development in our cohort was 0.46%. This value is slightly higher than that reported in the study by Uemura et al (0.37%) which included both H pylori infected and uninfected individuals.4 We also showed that eradication of H pylori infection significantly retarded progression of IM. As shown in table 3 ▶, subjects randomised to receive anti-H pylori therapy had a significantly lower risk of IM progression than those who received placebo, regardless of the final H pylori status (OR 0.63). The risk of progression was further reduced in those with successful H pylori eradication in the OAC group (OR 0.48). After adjusting for various confounding factors, it was determined that subjects with persistent H pylori infection had more than a twofold increased risk of IM progression than those who were negative for H pylori, irrespective of treatment allocation. This finding strongly supports the notion that successful eradication of the bacterium could prevent progression of precancerous gastric lesions.

As in our previous analysis,10 results from this five year analysis further confirmed that age is an important factor governing the rate of histological progression. Subjects >45 years had about a twofold increased risk of IM progression than younger subjects. The highest risk of progression was in subjects >45 years of age with persistent H pylori infection. In keeping with this finding, You et al concluded that the risk of progression to gastric cancer was threefold higher in subjects >45 years compared with those <45 years.14 Although it appeared that eradication of H pylori would most benefit subjects >45 years, our analysis showed that eradication of the bacterium also significantly retarded the rate of progression in younger subjects (fig 4 ▶). Thus eradication of H pylori should be considered in all age groups to prevent deterioration in gastric histology.

In our analysis, modifiable environmental factors, including alcohol use and drinking water from a domestic well, increased the risk of IM progression. While there are a number of studies addressing the role of tobacco and alcohol on premalignant gastric lesions,13,18 the role of the source of drinking water has received little attention. A previous study from Changle, China, showed that the source of drinking water may have a strong correlation with gastric cancer incidence.19 Gastric cancer mortality was highest among those drinking river water, which was significantly higher than those drinking shallow well water and tap water. One of the plausible explanations for this observation may be related to the mineral and trace element concentrations of drinking water. It has been shown that higher concentrations of selenium and zinc in drinking water may aid in preventing gastric carcinogenesis.20 Alternatively, the use of well water may just be a surrogate indicator of the lower socioeconomic class of these study subjects.

It is well known that not all subjects infected with H pylori develop gastric cancer. In fact, duodenal ulcer and gastric cancer, both aetiologically linked to chronic H pylori infection, are considered to be two ends of the clinical spectrum of H pylori infection. While duodenal ulcer is characterised by antral predominant gastritis and acid hypersecretion, gastric cancer is characterised by corpus predominant or pangastritis with acid hyposecretion. This divergent clinical outcome may be related to the genetic makeup of the host and polymorphism in the proinflammatory cytokines.21,22 In this study, we found that duodenal ulcer patients had a lower rate of IM progression and the risk of progression was approximately 75% lower than those without duodenal ulcer. Uemura et al also found that the risk of gastric cancer development was lower in patients with duodenal ulcers but higher in patients with gastric ulcers and non-ulcer dyspepsia.4 With the lower progression rate of gastric precancerous lesions in patients with duodenal ulcer, our finding may offer a plausible explanation for the reduced risk of gastric cancer development in these patients.

In addition to the grading of IM, there are data to suggest that subtyping of IM may further stratify the risk of gastric cancer development.23–25 Patients with type III or incomplete IM, which are characterised by the presence of columnar and globet cells secreting sulfomucins, have the highest cancer risk. However, this typing is not easily reproducible due to the focal nature of gastric IM. Instead, it has been proposed that the pattern, extent, and severity of IM may be more reliable predictors of cancer risk.26 Consistent with this, we found in the present study that the risk of IM progression was higher in those with more severe (fig 2 ▶) and more extensive IM (fig 1 ▶) at baseline. On the other hand, we failed to show any significant association between the pattern of gastritis and rate of IM progression.

Gastric IM is multifocal and is mostly indistinguishable from inflamed gastric mucosa by the naked eye or even by chromoendoscopy.27 One of the limitations of the present and other interventional studies of gastric precancerous lesions is the focal nature of these lesions which make the results subject to sampling error. To overcome this limitation, our protocol dictated the need to obtain gastric biopsies from the same landmark (that is, the mid point of the antrum and corpus in the lesser and greater curves of the stomach, during each endoscopy). Moreover, recruiting a larger sample size, incorporating a control group, and using paired tissue samples from the same subjects may have partially overcome the effects of apparent spontaneous regression of precancerous gastric lesions.

In conclusion, this five year randomised study showed that the risk of progression of gastric precancerous lesions was significantly lower in subjects with confirmed H pylori eradication or in those with duodenal ulcer. In contrast, subjects aged >45 years who drank alcohol or well water, had a higher risk of progression. Hence eradication of H pylori and lifestyle modifications may have a protective effect against gastric cancer development by retarding the progression of premalignant gastric lesions. We also identified a subgroup of infected individuals who were at high risk of histological progression that may warrant more intensive endoscopic surveillance to detect early gastric malignancy.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an unrestricted research grant from the Hong Kong Society of Digestive Endoscopy. The authors would like to thank the endoscopists and nurses of the Third Hospital of Peking University, Dr KF Chan for assistance on histological assessment, and Dr Rupert Leong for proofreading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

IM, intestinal metaplasia

GA, glandular atrophy

OAC, omeprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin

OR, odds ratio

REFERENCES

- 1.Correa P . Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process. First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res 1992;52:6735–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, et al. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterol 1998;114:1169–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut 2001;49:347–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uemura N , Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med 2001;345:784–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uemura N , Mukai T, Okamoto S, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on subsequent development of cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1997;6:639–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohkusa T , Fujiki K, Takashimizu I, et al. Improvement in atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia in patients in whom Helicobacter pylori was eradicated. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:380–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van der Hulst RWM, van der Ende A, Dekker FW, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on gastritis in relation to cagA: A prospective 1-year follow-up study. Gastroenterology 1997;113:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tepes B , Kavcic B, Zaletel LK, et al. 2 to 4 years histological follow-up of gastric mucosa after H. pylori eradication. J Pathol 1999;188:24–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Correa P , Fontham ETH, Bravo JC, et al. Chemoprevention of gastric dysplasia: randomized trial of antioxidant supplements and anti-Helicobacter therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1881–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sung JJY, Lin SR, Ching JYL, et al. Atrophy and intestinal metaplasia one year after cure of H. pylori infection: a prospective, randomized study. Gastroenterology 2000;119:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blot WJ. Preventing cancer by disrupting progression of precancerous lesions. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1868–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou LY, Sung JJY, Lin SR, et al. A five-year follow-up study on the pathological changes of gastric mucosa after H. pylori eradication. Chin Med J 2003;116:11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russo A , Maconi G, Spinelli P, et al. Effect of lifestyle, smoking, and diet on development of intestinal metaplasia in H. pylori-positive subjects. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:1402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.You WC, Lee JY, Blot WJ, et al. Evolution of precancerous lesions in rural Chinese population at high risk of gastric cancer. Int J Cancer 1999;83:615–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, et al. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:1161–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rugge M , Correa P, Dixon MF, et al. Gastric dysplasia: the Padova international classification. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:167–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA. Pathology and genetics of tumors of the digestive system. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2000.

- 18.You WC, Zhang L, Gail MH, et al. Gastric dysplasia and gastric cancer: Helicobacter pylori, serum vitamin C, and other risk factors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1607–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang ZQ, He J, Chen W, et al. Relationship between different sources of drinking water, water quality improvement and gastric cancer mortality in Changle County—A retrospective-cohort study in high incidence area. World J Gastroenterol 1998;4:45–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakaji S , Fukuda S, Sakamoto J, et al. Relationship between mineral and trace element concentrations in drinking water and gastric cancer mortality in Japan. Nutr Cancer 2001;40:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan FKL, Leung WK. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet 2002;360:933–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH, et al. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of gastric cancer. Nature 2000;404:398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rokkas T , Filipe MI, Sladen GE. Detection of an increased incidence of early gastric cancer in patients with intestinal metaplasia type III who are closely followed up. Gut 1991;32:1110–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filipe MI, Munoz N, Matko I, et al. Intestinal metaplasia types and the risk of gastric cancer: a cohort study in Slovenia. Int J Cancer 1994;57:324–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung WK, Sung JJY. Review article: intestinal metaplasia and gastric carcinogenesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:1209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Zimaity HM, Ramchatesingh J, Saeed MA, et al. Gastric intestinal metaplasia: subtypes and natural history. J Clin Pathol 2001;54:679–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wo JM, Ray MB, Mayfield-Stokes S, et al. Comparison of methylene blue-directed biopsies and conventional biopsies in the detection of intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: a preliminary study. Gastroint Endosc 2001;54:294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]