Abstract

Background and aims: There is growing evidence that the response of hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b infected patients towards interferon (IFN) therapy is influenced by the number of mutations within the carboxy terminal region of the NS5A gene, the interferon sensitivity determining region (ISDR).

Patients and methods: In order to attain better insight into this correlation, a file comprising published data on ISDR strains from 1230 HCV genotype 1b infected patients, mainly from Japan and Europe, was constructed and analysed by logistic regression. Sustained virological response (SVR) was defined as negative HCV RNA six months after treatment.

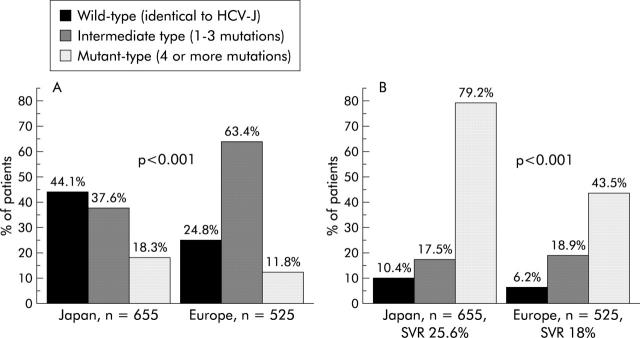

Results: The distribution of wild-, intermediate-, and mutant-type ISDR sequences differed significantly between Japanese (n = 655) (44.1%, 37.6%, and 18.3%) and European patients (n = 525) (24.8%, 63.4%, and 11.8%; p<0.001). There was a significant positive correlation between the number of ISDR mutations and SVR rate, irrespective of geographical region. The likelihood of SVR with each additional mutation within the ISDR was considerably more pronounced in Japanese compared with European patients (odds ratios 1.82 v 1.39; p<0.001). Pretreatment viraemia of <6.6 log copies/ml and ISDR mutant-type infection was associated with an SVR rate of 97.1% in Japanese patients but only 52.5% in European patients. Pretreatment viraemia was a stronger predictor of SVR than ISDR mutation number in Japanese patients whereas in European patients both parameters had similar predictive power.

Conclusion: These data support the concept that mutant-type ISDR strains may represent a subtype within genotype 1b with a more favourable response towards IFN therapy.

Keywords: sustained virological response, viraemia, geographical difference, interferon sensitivity determining region

Interferon (IFN) therapy alone or in combination with ribavirin is currently the only available treatment for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. However, this approach is not effective in all patients. Little is known about factors that can predict a favourable or unfavourable response to IFN treatment. The only accepted predictive parameters are age, pretreatment viral load, fibrosis stage, and HCV genotype. Thus nearly all patients with HCV genotype 2 and 3 infection can be cured by modern combination therapy, including pegylated IFN plus ribavirin. In contrast, patients with HCV genotype 1b infection, the prevalent genotype in Japan and Western countries, are poor responders and a sustained virological response (SVR) was observed in less than 10% after IFN monotherapy and in approximately 50% after combination therapy.1–4

Studies have been undertaken in recent years which tried to explain the resistance of genotype 1b infection to IFN therapy. Enomoto et al were able to demonstrate a strong correlation between the number of mutations within the carboxy terminal region of the NS5A gene spanning codons 2209–2248, the interferon sensitivity determining region (ISDR), and response to IFN therapy.5 Thus no patient infected with the wild-type ISDR sequence (that is, identical to the prototype Japanese HCV strain (HCV-J)) responded to IFN therapy whereas all patients infected with the “mutant-type”, defined by four or more amino acid substitutions in this region, showed an SVR.6 These initial findings have been confirmed by other Japanese studies but controversial data were reported from other parts of the world, particularly from Europe and the USA. This may indicate that geographical factors account for different sensitivities of HCV genotype 1b infection towards antiviral therapy.7–34

We therefore investigated, in a meta-analysis comprising published data on 1230 ISDR sequences, the relationship between the number and patterns of mutations within the ISDR and responsiveness to IFN therapy with respect to geographical area.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Patients

A literature search with the goal of finding articles on HCV ISDR sequences was conducted using the MEDLINE database. The following criteria had to be fulfilled to be included in this analysis: consecutive patients had to belong to genotype 1b and had to be treated with IFN alone or in combination with ribavirin. Dual publications were excluded. Only those patients who became negative for serum HCV RNA six months after therapy were defined as SVR; others were labelled as non-responders (NR). Twenty two HCV infected patients from our department were also included in this study. In these patients, HCV genotyping and HCV RNA quantitation as well as sequencing of the NS5A-ISDR region were performed as described elsewhere.20

Data on ISDR strains from 1230 patients were collected (table 1 ▶). They were analysed with respect to the number of mutations in the ISDR sequences and their relationship to the outcome of IFN therapy. We found 278 IFN sensitive strains and 952 IFN resistant strains, derived from patients with SVR and NR, respectively.

Table 1.

Sustained response to treatment with interferon (IFN) alone or in combination with ribavirin in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1b infection according to the number of mutations in the interferon sensitivity determining region

| Author | Total | Wild-type (no mutation) | Intermediate type (1–3 mutations) | Mutant-type (⩾4 mutations) | p Value* |

| Japan | |||||

| Komatsu 199735 | 3/10 (30.0%) | 3/8 (37.5%) | 0/2 | 0/0 | NS |

| Kurosaki 19977 | 4/22 (18.2%) | 0/10 | 0/6 | 4/6 (66.7%) | 0.002 |

| Fukuda 19988 | 5/31 (16.1%) | 0/16 | 2/11 (18.2%) | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0.001 |

| Arase 19999 | 8/46 (17.4%) | 3/25 (12.0%) | 2/16 (12.5%) | 3/5 (60.0%) | 0.049 |

| Nakano 199910 | 12/52 (23.1%) | 2/21 (9.5%) | 5/23 (21.7%) | 5/8 (62.5%) | 0.005 |

| Murashima 199911 | 24/57 (42.1%) | 1/17 (5.9%) | 6/16 (37.5%) | 17/24 (70.8%) | 0.001 |

| Chayama 199712 | 31/103 (30.1%) | 9/47 (19.1%) | 8/37 (21.6%) | 14/19 (73.7%) | 0.001 |

| Watanabe 200113 | 81/334 (24.3%) | 12/145 (8.3%) | 20/135 (14.8%) | 49/54 (90.7%) | 0.001 |

| Total | 168/655 (25.6%) | 30/289 (10.4%) | 43/246 (17.5%) | 95/120 (79.2%) | 0.001 |

| Taiwan | |||||

| Lo 200114 | 6/11 (54.5%) | 5/9 (55.6%) | 1/2 (50.0%) | 0/0 | NS |

| Europe | |||||

| McKechnie 200015 | 2/8 (25.0%) | 0/1 | 1/4 (25.0%) | 1/3 (33.3%) | NS |

| Rispeter 199816 | 4/13 (30.8%) | 0/0 | 4/13 (30.8%) | 0/0 | NS |

| Frangeul 199817 | 3/17 (17.6%) | 0/3 | 3/13 (23.1%) | 0/1 | NS |

| Duverlie 199818 | 8/19 (42.1%) | 1/5 (20.0%) | 5/12 (41.7%) | 2/2 (100.0%) | NS |

| This study† | 6/22 (27.3%) | 2/3 (66.7%) | 3/16 (18.8%) | 1/3 (33.3%) | NS |

| Zeuzem 199719 | 1/22 (4.5%) | 0/11 | 1/10 (10.0%) | 0/1 | NS |

| Berg 200020† | 3/23 (13.0%) | 0/4 | 2/17 (11.8%) | 1/2 (50%) | NS |

| Stratidaki 200121 | 2/28 (7.1%) | 0/5 | 0/21 | 2/2 (100.0%) | 0.001 |

| Gerotto 200022 | 8/30 (26.7%) | 1/6 (16.7%) | 5/18 (27.8%) | 2/6 (33.3%) | NS |

| Saiz 199823 | 8/36 (22.2%) | 0/10 | 2/20 (10.0%) | 6/6 (100.0%) | 0.001 |

| Khorsi 199724 | 17/43 (39.5%) | 3/13 (23.1%) | 13/28 (46.4%) | 1/2 (50.0%) | NS |

| Squadrito 199725 | 5/48 (10.4%) | 0/14 | 4/28 (14.3%) | 1/6 (16.7%) | NS |

| Halfon 200026 | 8/70 (11.4%) | 0/16 | 7/38 (18.4%) | 1/16 (6.3%) | NS |

| Sarrazin 199927† | 12/72 (16.7%) | 0/19 | 9/47 (19.1%) | 3/6 (50.0%) | 0.004 |

| Puig-Basagoiti 200128 | 11/74 (14.9%) | 1/20 (5.0%) | 4/48 (8.3%) | 6/6 (100.0%) | 0.001 |

| Total | 98/525 (18.0%) | 8/130 (6.2%) | 63/333 (18.9%) | 27/62 (43.5%) | 0.001 |

| USA | |||||

| Murphy 200229 | 1/5 (20.0%) | 0/1 | 1/4 (25.0%) | 0/0 | NS |

| Hofgärtner 199730 | 1/6 (16.7%) | 0/1 | 1/5 (20.0%) | 0/0 | NS |

| Nousbaum 200031 | 2/6 (33.3%) | 0/1 | 2/5 (40.0%) | 0/0 | NS |

| Chung 199932 | 2/22 (9.1%) | 0/6 | 2/11 (18.2%) | 0/5 | NS |

| Total | 6/39 (15.4%) | 0/9 (0%) | 6/25 (24.0%) | 0/5 | NS |

| Total | 278/1230 (22.6%) | 43/437 (9.8%) | 113/606 (18.6%) | 122/187 (65.2%) | 0.001 |

Values are number of patients with a sustained response/total number of patients (%).

NS, not significant.

*χ2 test;

†IFN in combination with ribavirin.

Phylogenetic analysis and secondary structure

Multiple sequence alignments were performed with the CLUSTALW program, version 6. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by means of the Phylogeny Interference Package (PHYLIP, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA) version 3.57c.36 Evolutionary distances were estimated using the DNAdist program and phylogenetic trees were constructed with NEIGHBOR (PHYLIP). Additionally, Seqboot (PHYLIP) was used to create 100 replicates for calculation of bootstrap values.37 The program used for conformational analysis was Protean version 5.03 (1994-002 DNASTAR.Inc).38

Statistical analysis

Analysis of continuous variables was performed using the Mann-Whitney or Student’s t test, and analysis of categorical variables with the χ2 test. For adjustment of multiple testing of several ISDR sites, the Bonferroni correction by factor 40 was applied. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to examine simultaneously the influence of several factors on viral response. Prognostic factors between European and Japanese studies were compared using interaction terms in logistic regression analyses. The level of significance was 0.05 (two sided) in all statistical tests. All analyses were carried out using SPSS Inc. for Windows (release 11.0; Chicago, Illinois, USA).

RESULTS

Geographical distribution of ISDR mutations

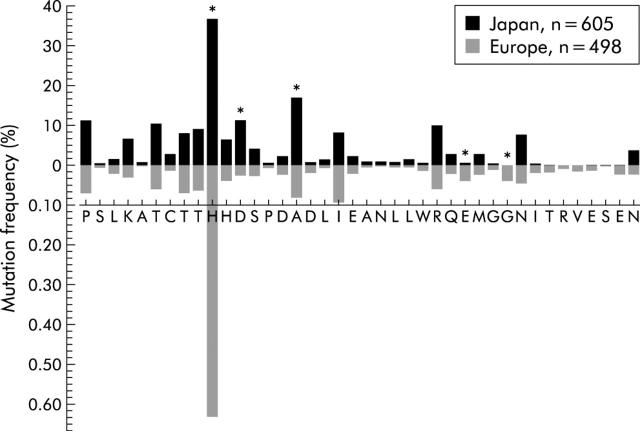

Following Enomoto’s classification, it emerged that the distribution of wild- (identical to HCV-J), intermediate- (1–3 mutations), and mutant- (⩾4 mutations) type ISDR sequences was significantly different in Japan compared with Europe (fig 1A ▶). In detail, only five of 40 ISDR positions (H 2218, D 2220, A 2224, E 2236, G 2239) showed a significant difference in mutation frequency between Japanese and European ISDR strains (fig 2 ▶).

Figure 1.

Distribution of wild-, intermediate-, and mutant-type interferon sensitivity determining region (ISDR) sequences (A) and percentage of sustained virological response (SVR) in patients infected with wild-, intermediate-, and mutant-type ISDR strains in Japan and Europe (B).

Figure 2.

Frequency of mutations at each amino acid position of the interferon sensitivity determining region (ISDR) in Japanese in comparison with European patients. Differences between Japanese and European patients were tested by χ2 test after Bonferroni correction by a factor 40 (equal to the number of positions tested, equal to the number of amino acids of ISDR, respectively). *ISDR positions significantly different between Japan and Europe.

ISDR mutations in relation to SVR

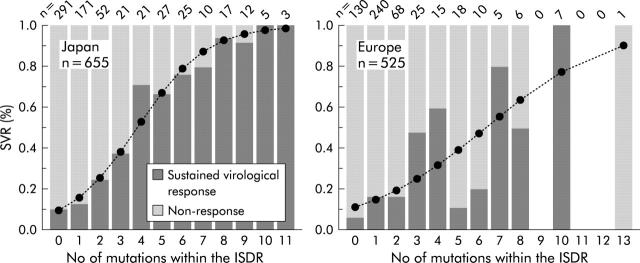

Clear positive correlations between SVR and types of ISDR sequences were demonstrated for Japanese as well as European patients (table 1 ▶). However, SVR rates in Japanese patients infected with the mutant ISDR type were higher compared with European patients (fig 1B ▶). SVR increased with each additional number of mutations within the ISDR but this relationship was more pronounced in Japanese patients (odds ratio (OR) 1.82 v 1.39; p<0.001) (fig 3 ▶).

Figure 3.

Sustained virological response (SVR) rates according to number of mutations within the interferon sensitivity determining region (ISDR) in Japan and Europe. Significant correlation between number of ISDR mutations was noted in both Japanese and European patients. With each additional mutation, the SVR likelihood was higher in Japanese in comparison with European patients (odds ratio 1.82 v 1.39; p<0.001). Logistic regression lines are represented as broken lines and symbols.

OR values for SVR with respect to mutation frequency at single ISDR sites were generally higher in Japanese patients (table 2 ▶). In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, the mutation frequency at any one of 40 ISDR sites did not improve the likelihood of an SVR compared with the total number of mutations per individual.

Table 2.

Odds ratios (OR) for a sustained virological response (SVR) with respect to mutation frequency at each of 40 interferon sensitivity determining region (ISDR) sites in Japanese and European patients

| ISDR | Japan OR (95% CI) | Europe OR (95% CI) |

| P 2209 | 27.46 (13.6–55.5) | 3.25 (1.6–6.8) |

| S 2210 | 6.0 (0.5–67.3) | 0.81 (0.7–0.8) |

| L 2211 | 25.21 (3.1–203.2) | 0.18 (0.1–0.2) |

| K 2212 | 7.29 (3.7–14.5) | 1.70 (0.5–5.5) |

| A 2213 | 7.71 (1.5–40.1) | * |

| T 2214 | 16.8 (8.8–32.0) | 5.12 (2.4–11.0) |

| C 2215 | 15.25 (4.3–53.8) | 6.43 (1.1–39.1) |

| T 2216 | 16.87 (8.0–35.8) | 1.56 (0.7–3.5) |

| T 2217 | 8.78 (4.8–16.1) | 3.04 (1.4–6.5) |

| H 2218 | 2.50 (1.7–3.6) | 1.99 (1.2–3.3) |

| H 2219 | 6.46 (3.3–12.7) | 1.64 (0.6–4.7) |

| D 2220 | 5.20 (3.1–8.8) | 0.80 (0.7–0.8) |

| S 2221 | 17.98 (6.1–53.2) | 3.09 (1–9.97) |

| P 2222 | 0.24 (0.2–0.3) | 0.81 (0.7–0.8) |

| D 2223 | 4.03 (1.5–11.0) | 2.86 (0.8–10.3) |

| A 2224 | 5.1 (3.3–8.0) | 9.73 (4.9–19.7) |

| D 2225 | 2.01 (0.3–12.2) | 4.31 (1.1–17.6) |

| L 2226 | 10.93 (2.2–53.2) | 0.81 (0.7–0.8) |

| I 2227 | 13.74 (6.8–27.6) | 3.56 (1.9–6.8) |

| E 2228 | 7.93 (2.5–25.7) | 8.84 (2.2–36.0) |

| A 2229 | 15.45 (1.8–133.3) | 0.19 (0.1–0.2) |

| N 2230 | 6.13 (1.1–33.8) | * |

| L 2231 | 12.28 (1.4–110.8) | 0.80 (0.7–0.8) |

| L 2232 | 3.84 (1.0–14.5) | 0.81 (0.7–0.8) |

| W 2233 | 9.12 (0.9–88.7) | 17.39 (2.0–157.4) |

| R 2234 | 7.29 (4.1–12.8) | 1.17 (0.4–3.2) |

| Q 2235 | 10.52 (3.4–32.8) | 3.44 (0.9–13.1) |

| E 2236 | 9.15 (0.9–88.6) | 1.64 (0.6–4.7) |

| M 2237 | 2.75 (1.0–7.3) | 0.80 (0.7–0.8) |

| G 2238 | 6.06 (0.5–67.3) | 4.24 (0.6–30.5) |

| G 2239 | 0.74 (0.7–0.8) | 7.29 (2.7–19.3) |

| N 2240 | 18.38 (8.4–40.4) | 2.71 (1.1–6.7) |

| I 2241 | 1.50 (0.1–16.7) | 2.55 (0.6–10.9) |

| T 2242 | 0.75 (0.7–0.8) | 0.80 (0.7–0.8) |

| R 2243 | * | 0.80 (0.7–0.8) |

| V 2244 | * | 8.68 (1.6–48.1) |

| E 2245 | 0.75 (0.7–0.8) | 17.39 (1.9–157.4) |

| S 2246 | 0.75 (0.7–0.8) | * |

| E 2247 | 0.25 (0.2–0.3) | 10.43 (2.7–41.1) |

| N 2248 | 11.29 (4.1–31.1) | 2.86 (0.8–10.3) |

*No mutation.

The frequency of individual amino acid substitutions, which occurred only in strains isolated from patients with SVR or NR, was low (<5%) and had no statistical relevance in the prediction of SVR.

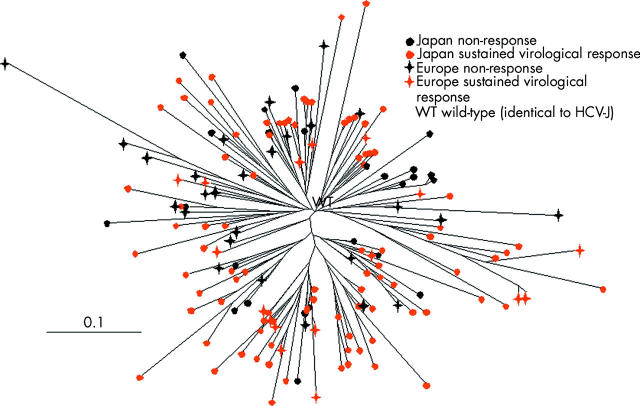

Phylogenetic and hydrophobicity analysis of ISDR

Neither cluster of ISDR isolates recovered from Japanese or European patients nor cluster of IFN sensitive and IFN resistant ISDR isolates into different branches could be obtained by phylogenetic tree analysis (fig 4 ▶). In spite of the high diversity of amino acid substitutions, hydrophobic plots, calculated by the method of Kyte-Doolittle, demonstrated that these substitutions had no major influence on the hydrophobicity of the ISDR protein.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of 158 interferon sensitivity determining region (ISDR) sequences with four or more mutations recovered from 178 Japanese and European patients with a non-response or sustained virological response to treatment. The scale bars represent 10%.

Factors affecting SVR

Forty four European patients received IFN in combination with ribavirin (table 1 ▶). Combination therapy influenced neither the overall percentage of SVR (18.3% in patients with IFN monotherapy versus 25% in patients with combination therapy; p = 0.31) nor the proportion of SVR with respect to ISDR sequence type in the European patient group (p = 0.35, interaction term “number of mutations” with” therapy” in logistic regression analysis for SVR). Although not significant, the likelihood of SVR with each additional mutation within the ISDR was higher in patients receiving IFN in combination with ribavirin in comparison with patients receiving IFN alone (OR 1.67 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.10–2.53) versus 1.36 (95% CI 1.21–1.53); p = 0.33).

Pretreatment viral loads were available in 459 Japanese and 315 European patients. A median HCV RNA concentration of 6.6 log copies/ml served as a cut off level to differentiate between patients with high or low viraemia. Regardless of the ISDR sequence type, pretreatment viraemia of ⩾6.6 log copies/ml was associated with an SVR rate of 0% in Japanese but 8.8% in European patients, whereas pretreatment viraemia of <6.6 log copies/ml was associated with an SVR rate of 86.6% in Japanese and only 21.3% in European patients (table 3 ▶). Moreover, ISDR mutant-type infection and pretreatment viraemia of <6.6 log copies/ml were associated with an SVR rate of 97.1% in Japanese but only 52.4% in European patients (table 3 ▶).

Table 3.

Relationship between sustained virological response (SVR) and pretreatment viral level, geographical area, and interferon sensitivity determining region (ISDR) sequence type.

| Pretreatment viraemia | ISDR type | Japan | Europe | ||

| NR | SVR | NR | SVR | ||

| ⩾6.6 log copies/ml* | Wild | 171 (100%) | — | 35 (100%) | — |

| Intermediate | 144 (100%) | — | 71 (88.8%) | 9 (11.3%) | |

| Mutant | 10 (100%) | — | 19 (86.4%) | 3 (13.6%) | |

| Total | 325 (100%) | — | 125 (91.2%) | 12 (8.8%) | |

| <6.6 log copies/ml* | Wild | 10 (32.3%) | 21 (67.7%) | 39 (95.1%) | 2 (4.9%) |

| Intermediate | 6 (17.6%) | 28 (82.4%) | 91 (78.4%) | 25 (21.6%) | |

| Mutant | 2 (2.9%) | 67 (97.1%) | 10 (47.6%) | 11 (52.4%) | |

| Total | 18 (13.4%) | 116 (86.6%) | 140 (78.7%) | 38 (21.3%) | |

For each of the 12 subgroups defined by the combinations of pretreatment viraemia, continent, and ISDR sequence type, the number (%) of patients is given. Patients with high pretreatment viral levels and SVR were only observed in European studies. In contrast, SVR rates were higher in Japanese patients with low pretreatment viral levels. SVR was dependent on the ISDR sequence type in both areas

NR, non-responders.

*6.6 log copies/ml = median viraemia.

The ISDR sequence type was a significant response predictor in patients with a pretreatment viral load of <6.6 log copies/ml in Japan (OR 3.56 (95% CI 1.78–7.13); p<0.001) and in Europe (OR 4.41 (95% CI 2.08–9.36); p<0.001) (table 3 ▶). All Japanese patients with a pretreatment viral load of ⩾6.6 log copies/ml were non-responders, and thus no dependency on ISDR sequence type was detected. In European patients with a pretreatment viral load of ⩾6.6 log copies/ml, a non-significant dependency (OR 2.59 (95% CI 0.96–7.01); p = 0.055) was observed (table 3 ▶).

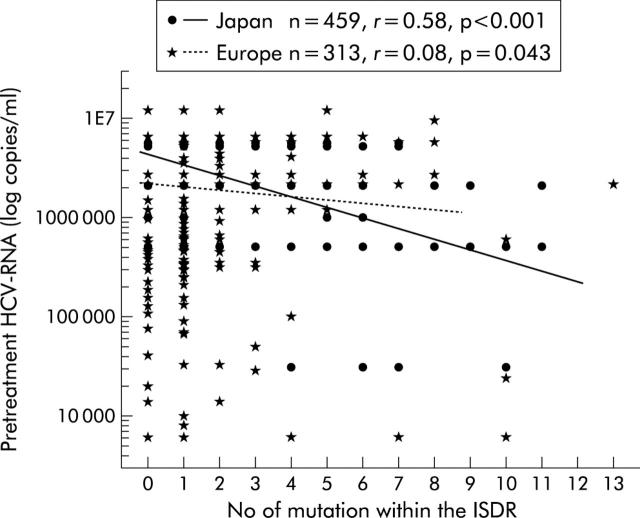

A negative correlation between the number of ISDR mutations and pretreatment viral load was observed in Japanese (r = 0.58, p<0.001) as well as European patients (r = 0.08, p = 0.043) (fig 5 ▶). The difference between these correlation coefficients was significant (p = 0.001, interaction term between continent and ISDR mutations in a linear regression analysis for initial virus load).

Figure 5.

Correlation between pretreatment viral load and number of interferon sensitivity determining region (ISDR) mutations in Japanese and European patients. Logistic regression lines are represented by continuous and broken lines, and symbols. This difference in correlations was significant (p = 0.001, interaction term between continent and ISDR mutations in a linear regression analysis for initial virus load).

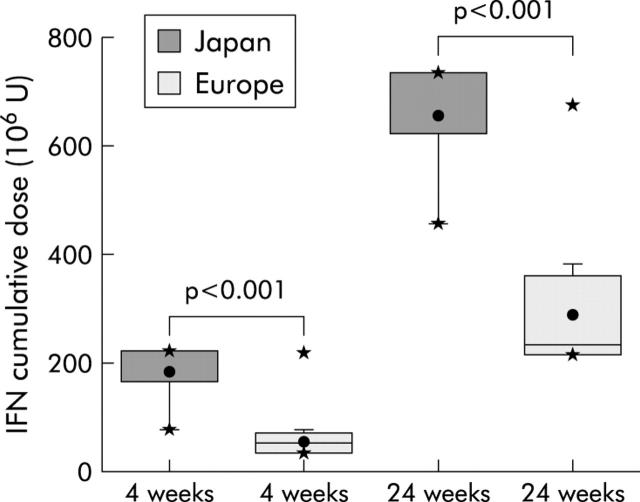

Cumulative IFN doses prescribed within the first four and 24 weeks were significantly higher in Japanese in comparison with European patients (four weeks: 185 (48) MU (range 80–224) v 56 (29) MU (range 36–219); 24 weeks: 655 (104) MU (range 456–736) v 290 (87) MU (range 216–675)) (fig 6 ▶).

Figure 6.

Cumulative interferon (IFN) dosages prescribed within the first four and 24 weeks in Japanese and European patients. The circle symbol represents the mean value; bottom and top edges of the box represent 25th and 75th percentile coefficient 1; whiskers indicate range 5–95 coefficient 1.5; and asterisks (*) represent 1% and 99% percentiles (minimum and maximum).

The influence of geographical area (Europe versus Japan) and cumulative IFN doses administered within the first four weeks with respect to SVR was analysed in a multiple logistic regression analysis (table 4 ▶). Because of the strong negative correlation with SVR in Japanese patients, thereby masking other statistical relationships, pretreatment viraemia was not included in this analysis. Thus according to this analysis, it cannot be concluded whether, after adjustment for the number of mutations, the different cumulative IFN dose or geographical area is responsible for the different response rates between Europe and Japan: inclusion of treatment dose makes geographical area insignificant and vice versa.

Table 4.

Multiple logistic regression analysis for viral response

| Model 1 (p<0.001, χ2 = 237.8, df = 1) | Model 2 (p<0.001, χ2 = 246.0, df = 2) | Model 3 (p<0.001, χ2 = 246.8, df = 2) | Model 4 (p<0.001, χ2 = 247.1, df = 3) | |

| No of mutations within the ISDR | 1.63 (1.51–1.75) | 1.62 (1.51–1.75) | 1.62 (1.51–1.75) | 1.62 (1.51–1.75) |

| Geographical area (Japan v Europe) | — | 1.61 (1.15–2.26) | — | 1.19 (0.60–2.36) |

| IFN cumulative dose in the first 4 weeks | — | — | 1.65 (1.18–2.30) | 1.41 (0.72–2.78) |

The effect of the number of mutations was not modified after inclusion of geographical area, interferon (IFN) cumulative dose, or both (models 1–4). Geographical area and IFN cumulative dose were almost equally important for the prognosis of sustained virological response (models 2 and 3). However, neither inclusion of IFN dose with number of mutations and geographical area nor inclusion of geographical area with number of mutations and IFN dose improved the model (model 4 compared with models 2 and 3, respectively).

For each model, the overall test for all covariates is given (degrees of freedom (df) are identical to numbers of covariates). Odds ratios (with 95% confidence intervals) are displayed for each covariate and separately for each model.

Model equations: for p = probability of sustained viral response, logit = log[p/(1−p)], X1 = number of ISDR mutations (quantitative variable), X2 coding the geographical area (0 = Europe, 1 = Japan), and X3 coding the cumulative dose (0 = less or equal to 100 …, 1 = more than 100 …).

The model equations are: logit = β0+β1X1 (model 1), logit = β0+β1X1+β2X2 (model 2), logit = β0+β1X1+β3X3 (model 3), and logit = β0+β1X1+β2X2+β3X3 (model 4).

DISCUSSION

A database comprising information on ISDR strains from 1230 genotype 1b patients, mainly from Japan and Europe, was constructed and analysed by logistic regression analysis with the aim of studying the relationship between number of mutations within the ISDR and response to IFN treatment.

A clear positive association was observed between the SVR rate and number of mutations within the ISDR, regardless of geographical region, but this correlation was more pronounced in Japan compared with Europe. SVR rates were nearly twice as high (79%) in Japanese patients infected with the mutant-type compared with the European group (43.5%). Furthermore, with each additional ISDR mutation there was a higher odds ratio for SVR in Japanese compared with European patients.

In two earlier studies it was suggested that these differences in SVR rates could be partially attributed to under representation of the mutant-type in European population.33,34 However, in this meta-analysis conducted in a much larger population, the mutant-type was approximately equally represented in both geographical areas. Therefore, the stronger correlation between ISDR mutation and SVR rate observed in Japanese patients cannot be explained by a different geographical distribution of ISDR mutations.

Treatment regimen (that is, IFN dose or IFN plus ribavirin combination therapy) is another factor which may account for the observed differences in SVR rates between Japan and Europe. Thus Japanese patients received significantly higher cumulative IFN doses within the first 4–24 weeks than European patients. In European patients who received IFN plus ribavirin, there was a non-significant trend for a higher SVR likelihood with each additional ISDR mutation in comparison with those who received IFN alone. However, the question of whether the different treatment regimens or geographical factors are mainly responsible for differences in SVR rates observed between Japanese and European patients cannot be answered.

Pretreatment hepatitis C viraemia was a strong predictor of SVR. In the presence of pretreatment HCV RNA levels ⩾6.6 log copies/ml, no SVR was achieved in Japanese patients in contrast with European patients who showed an SVR of 8.8% under these conditions. On the other hand, low pretreatment HCV RNA levels in association with a mutant-type infection resulted in SVR rates of up to 97% in Japanese patients while European patients had rates of only 52.4%.

There was further evidence, derived from the multivariate analysis, that in Japanese patients the pretreatment viraemia parameter is a much stronger predictor of SVR than number of ISDR mutations, and this has also been described by Chayama and colleagues.12 In contrast, in European patients both factors (that is, number of ISDR mutations and HCV RNA levels) were of similar importance. Furthermore, a negative correlation between number of mutations within the ISDR region and pretreatment viral load was observed in both Japanese and European patients. European or North American patients infected with strains with multiple ISDR mutations have been shown to respond with a more rapid first and second phase viral decline in the course of IFN therapy.20,38 Taken together, these data support the existence of geographical differences in HCV genotype 1b infection which can be attributed to a genetic viral factor (that is, the existence of a Japanese specific group of HCV 1b isolates with different biological properties) or to an as yet unidentified host or racial factor.10,39,40 However, data concerning pretreatment HCV RNA concentrations were based on different methods of quantification, and therefore the analysis must be interpreted with caution.

There was a high diversity of individual ISDR mutations among the different strains regardless of whether they were isolated from responders or non-responders. As shown by multivariate logistic regression analysis, the mutation frequency at any ISDR site had no effect on SVR rates compared with the total number of mutations per individual. Phylogenetic analysis revealed no clusters that could be correlated with geographical area or treatment response. In spite of the high diversity, no important changes in the hydrophobicity of the ISDR protein were observed. Thus it seems that IFN sensitive phenotype relates rather to the number of substitutions and not to specific substitutions pattern of the ISDR.

The biological role of ISDR is not clear. Studies have revealed that the NS5A protein binds and represses the IFN induced double stranded RNA dependent protein kinase (PKR). The PKR interacting domain of NS5A, spanning amino acid positions 2209–2274, comprises the ISDR, and the NS5A-PKR interaction is disrupted by the ISDR mutation which corresponds to IFN sensitive HCV, resulting in repression of PKR function and phosphorylation of eIF-2 alpha.41 NS5A expression blocked the antiviral effects of IFN in human cells in a quantitative manner and was genotype dependent, NS5A of genotype 1b being more potent in blocking the antiviral effects of IFN than NS5A from genotype 1a.42,43 Thus the IFN sensitive ISDR phenotype could influence post translational processing of NS5A and thereby in conjunction with other viral or host factors acting to direct the replication of the HCV genome.44

Mutations in other regions of the NS5A protein (that is, PKR binding domain, V3 region, carboxy-terminal) could also be correlated with SVR.18,19,22,31 Sarrazin et al identified mutations within the NS5A region, spanning amino acid positions 2350–2370, to be relevant for treatment response.45 However, the fact that some European patients showing either no mutation within the ISDR or high pretreatment viral load have been able to eliminate the virus indicates the presence of other unidentified host or viral factors that influence the response to antiviral treatment.

This meta-analysis suggests the existence of a subgroup of European patients which can be defined as non-responders. Thus no European patient infected with the ISDR wild-type and with a high pretreatment viraemia responded to IFN therapy. In contrast, European patients infected with the mutant ISDR type and expressing low pretreatment viral load were highly responsive to standard dose IFN monotherapy, hereby achieving SVR rates of 52.4% (table 3 ▶). This treatment response is similar to that of pegylated IFN plus ribavirin for HCV type 1 infection.46,47 In Japanese patients the situation is different. Regardless of ISDR type, a Japanese patient with a high pretreatment viraemia would not respond to treatment. Japanese patients infected with the ISDR mutant-type having a low pretreatment viraemia can achieve SVR rates of up to 100% when treated with high dose IFN. This is in accordance with the Markov decision analysis model proposed by Moriguchi et al which shows that IFN monotherapy has little effect when given to HCV genotype 1 infected patient who are older then 50 years, have hepatitis C viraemia exceeding 1.0 mEq/ml, and have no amino acid mutations in the ISDR.48

In conclusion, there is clear evidence from this meta-analysis for an association between number of ISDR mutations and SVR rate. It is however worthwhile further investigating whether ISDR mutations also influence response in those patients who have received combination therapy with pegylated IFN. In addition, these data imply that mutant ISDR strains represent a subtype with different biological properties within genotype 1b.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the German BMBF Network of Competence for Viral Hepatitis (Hep Net).

Abbreviations

SVR, sustained virological response

HCV, hepatitis C virus

IFN, interferon

ISDR, interferon sensitivity determining region

NR, non-response

OR, odds ratio

PKR, RNA dependent protein kinase

REFERENCES

- 1.Martinot-Peignoux M , Marcellin P, Pouteau M, et al. Pretreatment serum hepatitis C virus RNA levels and hepatitis C virus genotype are the main and independent prognostic factors of sustained response to interferon alfa therapy in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 1995;22:1050–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poynard T , Leroy V, Cohard M, et al. Meta-analysis of interferon randomized trials in the treatment of viral hepatitis C: effects of dose and duration. Hepatology 1996;24:778–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomized trial. Lancet 2001;358:958–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2002;347:975–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enomoto E , Sakuma I, Asahina Y, et al. Comparison of full-length sequences of interferon-sensitive and resistant hepatitis C virus 1b. J Clin Invest 1995;96:224–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enomoto E , Sakuma I, Asahina Y, et al. Mutations in the nonstructural protein 5A gene and response to interferon in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus 1b infection. N Engl J Med 1996;334:77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurosaki M , Enomoto N, Murakami T, et al. Analysis of genotypes and amino acid residues 2209 to 2248 of the NS5A region of hepatitis C virus in relation to the response to interferon-beta therapy. Hepatology 1997;25:750–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuda M , Chayama K, Tsubota A, et al. Predictive factors in eradicating hepatitis C virus using a relatively small dose of interferon. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998;13:412–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arase Y , Ikeda K, Chayama K, et al. Efficacy and changes of the nonstructural 5A GENE by prolonged interferon therapy for patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1b and a high level of serum HCV-RNA. Intern Med 1999;38:461–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakano I , Fukuda Y, Katano Y, et al. Why is the interferon sensitivity-determining region (ISDR) system useful in Japan? J Hepatol 1999;30:1014–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murashima S , Ide T, Miyajima I, et al. Mutations in the NS5A gene predict response to interferon therapy in Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis C and cirrhosis. Scand J Infect Dis 1999;31:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chayama K , Tsubota A, Kobayashi M, et al. Pretreatment virus load and multiple amino acid substitutions in the interferon sensitivity-determining region predict the outcome of interferon treatment in patients with chronic genotype 1b hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 1997;25:745–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe H , Enomoto N, Nagayama K, et al. Number and position of mutations in the interferon (IFN) sensitivity-determining region of the gene for nonstructural protein 5A correlate with IFN efficacy in hepatitis C virus genotype 1b infection. J Infect Dis 2001;183:1195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo S , Lin HH. Variations within hepatitis C virus E2 protein and response to interferon treatment. Virus Res 2001;75:107–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKechnie VM, Mills PR, McCruden EA. The NS5a gene of hepatitis C virus in patients treated with interferon-alpha. J Med Virol 2000;60:367–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rispeter K , Lu M, Zibert A, et al. The “interferon sensitivity determining region” of hepatitis C virus is a stable sequence element. J Hepatol 1998;29:352–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frangeul L , Cresta P, Perrin M, et al. Mutations in NS5A region of hepatitis C virus genome correlate with presence of NS5A antibodies and response to interferon therapy for most common European hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology 1998;28:1674–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duverlie G , Khorsi H, Castelain S, et al. Sequence analysis of the NS5A protein of European hepatitis C virus 1b isolates and relation to interferon sensitivity. J Gen Virol 1998;79:1373–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeuzem S , Lee JH, Roth WK. Mutations in the nonstructural 5A gene of European hepatitis C virus isolates and response to interferon alfa. Hepatology 1997;25:740–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berg T , Mas Marques A, Hohne M, et al. Mutations in the E2-PePHD and NS5A region of hepatitis C virus type 1 and the dynamics of hepatitis C viremia decline during interferon alfa treatment. Hepatology 2000;32:1386–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stratidaki I , Skoulika E, Kelefiotis D, et al. NS5A mutations predict biochemical but not virological response to interferon-alpha treatment of sporadic hepatitis C virus infection in European patients. J Viral Hepat 2001;8:243–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerotto M , Dal Pero F, Pontisso P, et al. Two PKR inhibitor HCV proteins correlate with early but not sustained response to interferon. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1649–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saiz JC, Lopez-Labrador FX, Ampurdanes S, et al. The prognostic relevance of the nonstructural 5A gene interferon sensitivity determining region is different in infections with genotype 1b and 3a isolates of hepatitis C virus. J Infect Dis 1998;177:839–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khorsi H , Castelain S, Wyseur A, et al. Mutations of hepatitis C virus 1b NS5A 2209–2248 amino acid sequence do not predict the response to recombinant interferon-alfa therapy in French patients. J Hepatol 1997;27:72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Squadrito G , Leone F, Sartori M, et al. Mutations in the nonstructural 5A region of hepatitis C virus and response of chronic hepatitis C to interferon alfa. Gastroenterology 1997;113:567–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halfon P , Halimi G, Bourliere M, et al. Integrity of the NS5A (amino acid 2209 to 2248) region in hepatitis C virus 1b patients non-responsive to interferon therapy. Liver 2000;20:381–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarrazin C , Berg T, Lee JH, et al. Improved correlation between multiple mutations within the NS5A region and virological response in European patients chronically infected with hepatitis C virus type 1b undergoing combination therapy. J Hepatol 1999;30:1004–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puig-Basagoiti F , Saiz JC, Forns X, et al. Influence of the genetic heterogeneity of the ISDR and PePHD regions of hepatitis C virus on the response to interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol 2001;65:35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy MD, Rosen HR, Marousek GI, et al. Analysis of sequence configurations of the ISDR, PKR-binding domain, and V3 region as predictors of response to induction interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy in chronic hepatitis C infection. Dig Dis Sci 2002;47:1195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofgartner WT, Polyak SJ, Sullivan DG, et al. Mutations in the NS5A gene of hepatitis C virus in North American patients infected with HCV genotype 1a or 1b. J Med Virol 1997;53:118–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nousbaum J , Polyak SJ, Ray SC, et al. Prospective characterization of full-length hepatitis C virus NS5A quasispecies during induction and combination antiviral therapy. J Virol 2000;74:9028–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung RT, Monto A, Dienstag JL, et al. Mutations in the NS5A region do not predict interferon-responsiveness in american patients infected with genotype 1b hepatitis C virus. J Med Virol 1999;58:353–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herion D , Hoofnagle JH. The interferon sensitivity determining region: all hepatitis C virus isolates are not the same. Hepatology 1997;25:769–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Witherell GW, Beineke P. Statistical analysis of combined substitutions in nonstructural 5A region of hepatitis C virus and interferon response. J Med Virol 2001;63:8–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Komatsu H , Fujisawa T, Inui A, et al. Mutations in the nonstructural protein 5A gene and response to interferon therapy in young patients with chronic hepatitis C virus 1b infection. J Med Virol 1997;53:361–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 1994;22:4673–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Felsenstein J . PHYLIP-phylogeny interference package (version 3.2). Cladistics 1989;5:164–6. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kyte J , Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol 1982;157:105–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Almarri A , El Dwick N, Al Kabi S, et al. Interferon-alpha therapy in HCV hepatitis: HLA phenotype and cirrhosis are independent predictors of clinical outcome. Hum Immunol 1998;59:239–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugimoto K , Stadanlick J, Ikeda F, et al. Influence of ethnicity in the outcome of hepatitis C virus infection and cellular immune response. Hepatology 2003;37:590–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gale MJ Jr, Blakely CM, Kwieciszewski B, et al. Control of PKR protein kinase by hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein: molecular mechanisms of kinase regulation. Mol Cell Biol 1998;18:5208–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paterson M , Laxton CD, Thomas HC, et al. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein inhibits interferon antiviral activity, but the effects do not correlate with clinical response. Gastroenterology 1999;117:1187–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polyak SJ, Paschal LDM, Mcardle S, et al. Characterization of the effects of hepatitis C virus non-structural 5A protein expression in human cell lines and on interferon-sensitive virus replication resistance during HCV infection. Hepatology 1999;29:1262–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pawlotsky JM, Germandis G. The non-structural 5A protein of hepatitis C virus. J Viral Hepat 1999;6:343–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarrazin C , Herrmann E, Bruch K, et al. Hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein and interferon resistance: a new model for testing the reliability of mutational analyses. J Virol 2002;76:11079–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2002;347:975–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet 2001;358:958–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moriguchi H , Uemura T, Kobayashi M, et al. Management strategies using pharmacogenomics in patients with severe HCV-1b infection: a decision analysis Hepatology 2002;36:177–85. [DOI] [PubMed]