Abstract

Background: Multiple treatment strategies for subjects with high grade dysplasia (HGD) in Barrett’s oesophagus (BO) have been suggested. However, it is unclear which of these strategies provides the greatest life expectancy, and the costs associated with the management strategies are unknown.

Aim: To compare the efficacy and cost effectiveness of competing management strategies for BO with HGD.

Methods: We created a decision analysis model in Data 4.0 to assess possible treatment strategies for BO with HGD. The strategies included: (1) no preventative strategy, (2) elective surgical oesophagectomy, (3) endoscopic ablation, and (4) surveillance endoscopy. The base case was a healthy 50 year old White male with an initial diagnosis of BO with HGD. The model allowed for complications of surgery, including death. Ablative therapy could cause stricture or perforation. Pathological misinterpretation was allowed, and modelled after reported rates. Estimates were derived from the literature for the rate of progression of HGD to cancer and for complication rates for the various treatment modalities. The endoscopic ablation arm was modelled as photodynamic therapy. Sensitivity analyses were performed over a wide range of cancer incidences, complication rates, and procedure costs.

Results: Endoscopic ablation was the most effective strategy, yielding 15.5 discounted quality adjusted life years (dQALY), compared with 15.0 for endoscopic surveillance and 14.9 for oesophagectomy. No preventative strategy was the most inexpensive option, yielding an average cost per quality adjusted life year of $54 (€44) per dQALY, but resulted in high rates of cancer. Endoscopic surveillance dominated oesophagectomy, being both less costly and more effective. The condition of extended dominance occurred when comparing endoscopic ablation to endoscopic surveillance because, although the total costs of ablation were greater than those of surveillance, it was less expensive to buy an additional life year using endoscopic ablation than endoscopic surveillance. The incremental cost effectiveness ratio when moving from no therapy to ablative therapy was a reasonable $25 621/dQALY (€21 009/dQALY). Sensitivity analysis demonstrated that when yearly rates of progression to cancer from HGD exceeded 30%, oesophagectomy became the most cost effective option.

Conclusions: A strategy of endoscopic ablation provided the longest quality adjusted life expectancy for BO with HGD. Although endoscopic surveillance was less expensive than endoscopic ablation, it was associated with shorter survival. Optimal utilisation of healthcare resources may be achieved with endoscopic ablative therapy for BO with HGD.

Keywords: Barrett’s oesophagus, oesophageal adenocarcinoma, cost effectiveness, endoscopic ablation, high grade dysplasia

Barrett’s oesophagus (BO), a metaplastic change of the lining of the oesophagus from squamous to specialised columnar, is associated with an increased risk of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus.1 However, few subjects with BO actually go on to develop cancer, and the risk of cancer in BO is thought to approximate 0.5% per year.2–5 The single most predictive known variable for progression to cancer in subjects with BO is the presence of dysplasia. Subjects with no dysplasia have extremely low cancer rates for the five years following the index endoscopy.6 Conversely, subjects with high grade dysplasia (HGD) have rates reported as high as 10% per year.7–10 Additionally, because endoscopic biopsies are random, the risk of metachronous cancer in subjects found to have BO with HGD is also high. Studies of subjects who have had resection for BO with HGD show that 40% or more may have previously undetected adenocarcinoma in their resection specimens.11–13

Because HGD represents a chance to intervene prior to the development of cancer, care of this condition has been debated. Some authorities, citing the high risk of metachronous cancer and the relatively high rates of progression, suggest oesophagectomy for those found to have BO with HGD.11,13–15 Other investigators have adopted the approach of watchful waiting, with frequent surveillance endoscopy in the hope of detecting any cancers that do occur in an early and resectable stage.8 Finally, innovations in endoscopic therapy have allowed for the development of multiple endoscopic ablative techniques designed to eradicate HGD and metaplasia, with replacement by “neosquamous” epithelium.16–19 Which of these three approaches to BO with HGD is most effective is unknown, and there are no randomised controlled trials comparing the effectiveness of ablative therapy, surgery, and endoscopic surveillance in the setting of HGD.

When competing strategies offer trade offs between risks and effectiveness, decision analysis models can be used to compare the costs and outcomes associated with the various strategies. The goal of this study was to develop a cost effectiveness model of the various competing strategies for the management of BO with HGD. Through this model, we wished to ascertain which of the three treatment strategies provided the longest quality adjusted life expectancy and which strategy was most cost effective. Our hypothesis was that a minimally invasive endoscopic intervention might be preferable to either intensive endoscopic surveillance or surgery.

METHODS

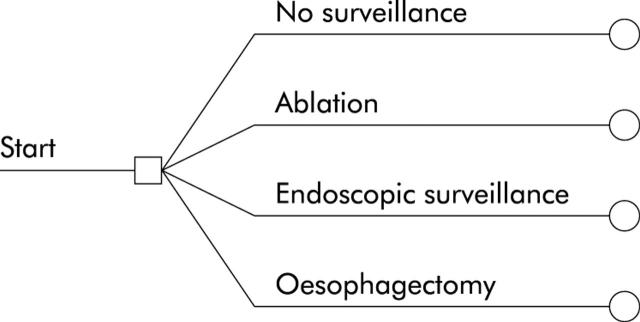

We used Data 4.0 (TreeAge, Williamstown, Massachusetts, USA) to develop a model simulating the three active treatment strategies for BO with HGD (fig 1 ▶). The perspective of the model was that of a third party payer. The base case consisted of a 50 year old Caucasian male with symptoms of reflux prompting endoscopy. Caucasian males are the demographic group at highest risk for adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus.20,21 Endoscopy demonstrates an appearance consistent with BO, and no nodules or masses present in the BO. Biopsies from this endoscopy demonstrated BO with HGD. The base case assumed no comorbid conditions precluding oesophagectomy.

Figure 1.

General structure of the tree. Subjects with an initial diagnosis of Barrett’s oesophagus with high grade dysplasia have four options available to them: no surveillance or other preventative measures (endoscopic ablation, endoscopic surveillance, or surgical oesophagectomy).

The strategies

Endoscopic surveillance

The intensive endoscopic surveillance protocol was modelled after the recently described Hines Veteran’s Affairs Medical Center protocol, which represents the longest published follow up of a cohort of subjects with HGD.8 Endoscopic surveillance consisted of four quadrant biopsies every 2 cm along the length of visible Barrett’s epithelium, and occurred every three months as long as HGD was detected, and for at least one year. If no further HGD was detected in subsequent surveillance, intervals were lengthened to every six months for one year, then yearly thereafter. A finding of cancer on any of these endoscopies led to oesophagectomy. Subjects who did not develop cancer could die from competing causes of mortality, or rarely, of complications related to surveillance endoscopy. Surveillance endoscopy was presumed to be terminated at death or age 80 years. In subjects under surveillance who did develop cancer, the majority underwent surgical oesophagectomy, with the remainder being unresectable. Subjects with unresectable adenocarcinoma accrued costs for palliative care and hospice, based on published rates. Palliation consisted of oesophageal stenting and/or administration of chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

The model allowed for misdiagnosis of histological specimens, known to be common in the setting of BO.22–24 For instance, a subject with true low grade dysplasia might be misread as having cancer and would then undergo the therapy for the diagnosed condition, not the actual condition. In this way, subjects never developing true cancer might suffer morbidity or mortality from complications of oesophagectomy for a presumed cancer. Rates of misinterpretation of histological specimens were derived from the published literature.

Endoscopic ablative therapy

The endoscopic ablative therapy modelled was photodynamic therapy (PDT).19 This therapy was modelled because it has the most extensive reported experience in the literature. Further details concerning this arm are discussed below. Sensitivity analyses were performed to simulate both less costly and less effective ablative therapies. In some cases, multiple estimates for effectiveness were available. If data were of similar quality, meta-analytic techniques were used to combine reported results from case series to obtain weighted estimates for effectiveness parameters. Often, data failed tests of homogeneity, suggesting that combination of the data would not be meaningful. In these cases, the largest reported cohort with the longest follow up was used in the base case, with sensitivity analysis used to simulate more extreme data.

Surgical oesophagectomy

Morbidity and mortality associated with surgical oesophagectomy were modelled based on published rates in the literature. In our base case scenario, oesophagectomy was assumed to have been performed at a major medical centre proficient in the procedure. In sensitivity analyses, the higher complication rates reported by community and low volume centres were modelled.25–27

The model

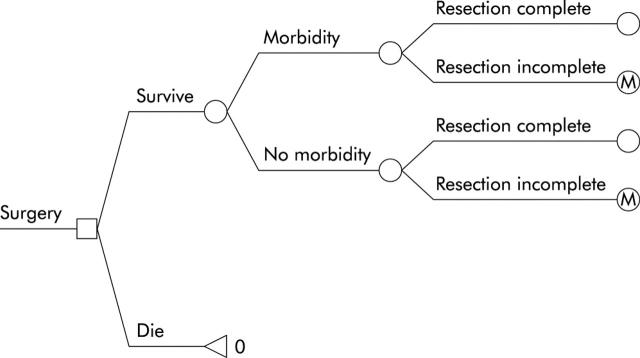

The model is a hybrid model of a linear decision tree which terminates in a Markov model for subjects not undergoing oesophagectomy. Initially, subjects with a new diagnosis of HGD are assigned to no preventative care or to undergo one of the three treatment strategies (fig 1 ▶). Subjects assigned to surgical oesophagectomy undergo their procedure, with the associated morbidity and mortality. Those successfully surviving their procedure are “cured” but live the remainder of their life with the somewhat diminished utility of a post-oesophagectomy patient (fig 2 ▶).

Figure 2.

Structure of the surgery sub-tree. Subjects choosing surgery may either survive or die from their resection. If they do survive, they may still suffer major morbidity such as anastomotic leakage, postoperative infection, or bleeding. Among those surviving, resection of Barrett’s oesophagus may be complete or incomplete. “M” denotes entry into the Markov model (see text for details).

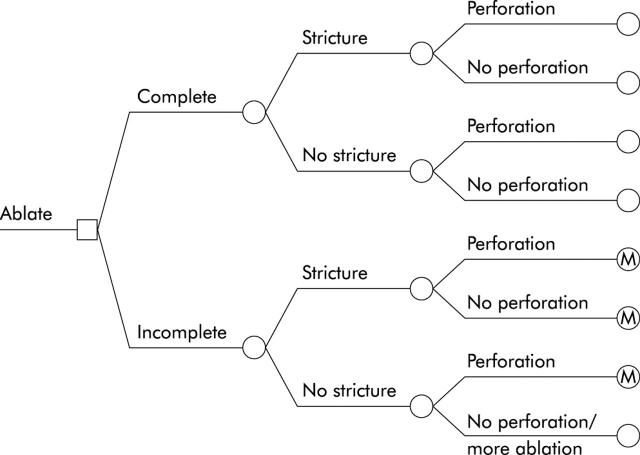

Subjects in the endoscopic ablation arm enter the decision tree and undergo up to three attempts at endoscopic therapy (fig 3 ▶). Ablative therapy has the potential to be ineffective, to ablate all BO, or to ablate only HGD, leaving residual BO. Ablative therapy may also lead to stricture formation or perforation, with increasing risk of complications based on the number of sessions performed. A portion of subjects with superficial cancers misdiagnosed as HGD may also be cured through ablative therapy. In subjects developing strictures, ablative therapy is halted, and the subject undergoes one or more endoscopic dilatations to ameliorate symptoms of dysphagia.28 They are then entered into the Markov model for continued surveillance. Subjects who undergo three sessions of ablative therapy without complete resolution of their BO also enter the Markov model for endoscopic surveillance. Ablative therapy that results in perforation leads to oesophagectomy, with its associated morbidity and mortality. In the base case scenario, even those who undergo successful ablative therapy continue to undergo endoscopic surveillance to assess for the development of malignancy in or below the neosquamous epithelium.

Figure 3.

Structure of the endoscopic ablation sub-tree. Subjects choosing endoscopic ablation may have either complete or incomplete ablation of their Barrett’s oesophagus. Whether ablation is complete or incomplete, subjects may develop strictures from their ablative therapy. Additionally, some subjects may develop a perforation of the oesophagus from their therapy. Note that subjects developing strictures receive no further attempts at ablative therapy and instead are given serial dilatation, then entry into endoscopic surveillance, denoted here with an “M,” for entry into the Markov model. Subjects who do not suffer perforation or stricture, but have incomplete ablation, receive up to two additional treatment sessions with ablative therapy.

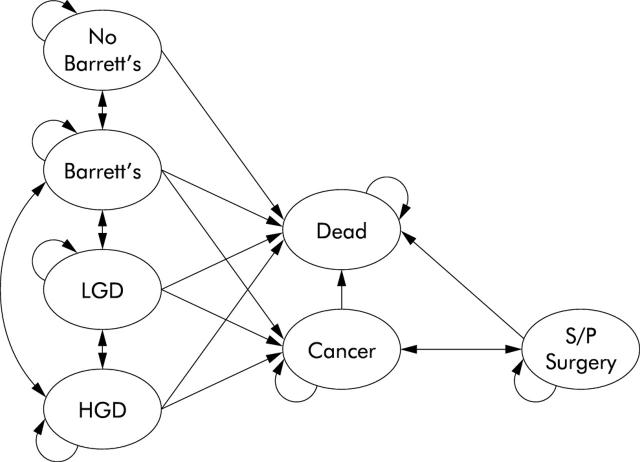

Subjects assigned to endoscopic surveillance immediately enter the Markov model and are allowed to transition to different states based on published rates. Transitions are made yearly, with patients redistributed to health states based on the parameters in table 1 ▶. Figure 4 ▶ demonstrates the Markov model. This part of the model is a modification of a previously described model.29

Table 1.

Model probability estimates and utilities

| Variable | Value | Range | Reference |

| Annual rate of progression of: | |||

| No dysplasia to cancer | 0.005 | 0.001–0.1 | 2–5,41 |

| Low grade dysplasia to cancer | 0.025 | 0.005–0.05 | 41 |

| High grade dysplasia to cancer | 0.025 | 0.001–0.3 | 8,9,41–43 |

| No dysplasia to high grade dysplasia | 0.01 | 0.0028–0.083 | 8,42,44–46 |

| Low grade dysplasia to high grade dysplasia | 0.05 | 0.01–0.078 | 41,42,47,48 |

| No dysplasia to low grade dysplasia | 0.05 | 0.01–0.078 | 4,42,44,48,49 |

| Annual rate of regression of: | |||

| No dysplasia to no Barrett’s | 0.0175 | 0.001–0.02 | 50 |

| Low grade dysplasia to no dysplasia | 0.63 | 0.50–0.80 | 44,47 |

| High grade dysplasia to no dysplasia | 0.10 | 0.01–0.15 | 9,47 |

| High grade dysplasia to low grade dysplasia | 0.07 | 0.05–0.10 | 8,9,47 |

| Treatment variables | |||

| Ablation causes stricture | 0.185 | 0.10–0.30 | 19,51 |

| Ablation causes perforation | 0.003 | 0.001–0.01 | 19,51,52 |

| Ablation eradicates all high grade dysplasia | 0.88 | 0.5–1.0 | 19,51–55 |

| Ablation eradicates all Barrett’s | 0.40 | 0.1–0.5 | 19,51–55 |

| Surgical resectability, cancer dx by surveillance | 0.95 | 0.85–1 | 56–58 |

| Surgical resectability, cancer dx symptomatically | 0.50 | 0.1–0.7 | 57–59 |

| Surgical mortality, cancer dx by surveillance | 0.027 | 0.025–0.1 | 60–63 |

| Surgical mortality, cancer dx symptomatically | 0.05 | 0.025–0.43 | 59–62 |

| Probability of major surgical morbidity | 0.15 | 0.05–0.50 | 64–67 |

| Surgery cures cancer, cancer dx by surveillance | 0.80 | 0.6–0.9 | 8,15,57,58,68 |

| Surgery cures cancer, cancer dx symptomatically | 0.20 | 0.1–0.43 | 57–59,68 |

| Death from endoscopy | 0.000021 | 0–0.00005 | 69–72 |

| Other major complication, endoscopy | 0.0013 | 0–0.005 | 69–72 |

| Mortality from surgery to repair perforation | 0.08 | 0.05–0.15 | 28,73–76 |

| Major morbidity from surgery to repair perforation | 0.20 | 0.10–0.40 | 73,76 |

| Misdiagnosis rates of dysplastic states | |||

| Cancer called high grade dysplasia | 0.175 | 0.01–0.20 | 22,23,30,77 |

| Cancer called low grade dysplasia | 0.05 | 0.01–.10 | 22,23,30,77 |

| High grade dysplasia called cancer | 0.11 | 0.01–0.20 | 22,24,30,77 |

| High grade dysplasia called low grade dysplasia | 0.115 | 0.01–0.20 | 22,24,30,77 |

| Low grade dysplasia called high grade dysplasia | 0.083 | 0.01–0.10 | 24,30,77 |

| Low grade dysplasia called cancer | 0.05 | 0.01–0.10 | 24,30,77 |

| Utilities | |||

| Barrett’s oesophagus | 1.0 | 0.79–1.0 | 30* |

| Oesophagectomy | 0.97 | 0.46–1.0 | 30,31 |

| Cancer | 0.50 | 0–1.0 | 29* |

*Utilities derived from 56 surveillance eligible patients at Durham VA Medical Center.

Figure 4.

The Markov model. Subjects who choose endoscopic surveillance, as well as those who choose no preventative strategy, enter the Markov model. Circles in the Markov model represent the disease states that are possible for subjects in the model. The arrows represent allowed transitions in the model. The rates at which subjects transition through the states are different for those who undergo endoscopic surveillance and those who do not. Note that transitions are allowed from greater to lesser degrees of dysplasia. The schematic is a simplified version of the much more complex model (>7000 nodes) because the actual model includes states of misdiagnosis (for example, low grade dysplasia diagnosed as high grade dysplasia). LGD, low grade dysplasia; HGD, high grade dysplasia; S/P, status post.

Transition rates from HGD to cancer, as well as transitions between other states demonstrated in fig 4 ▶, were modelled after transitions reported in the English language literature. Because some subjects who develop adenocarcinoma do so without being previously diagnosed with HGD, transitions from LGD to cancer and no dysplasia to cancer were also allowed. Regression of dysplasia (HGD to LGD or no dysplasia, LGD to no dysplasia) was also modelled. Estimates for rates of transitions, as well as the utilities used in the model, are shown in table 1 ▶. Ranges used for sensitivity analyses are also included.

The primary outcome of the analysis was the incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER). This figure represents the additional cost per life year saved when one moves from one strategy to another more effective, but more costly, strategy. We also sought to define the overall most effective strategy (that is, the strategy that provided the longest life expectancy regardless of cost) and mean cost per subject for each strategy.

Utility data

Patient preferences for living in various conditions were adjusted with utilities. This method allows subjects with disease to weight their preferences for living in a compromised health state, such as being status post-oesophagectomy, when compared with living in perfect health. Health utilities range from 1 (perfect health) to 0 (death). Utilities were derived from two sources. Utilities for living post-oesophagectomy have been previously reported.30,31 Utilities for living in states of endoscopic surveillance were derived from 56 veterans with BO undergoing endoscopic surveillance at the Durham Veterans’ Affairs Medical Center. These surveillance eligible patients were asked to rate quality of life using a visual analogue scale, after reading a one paragraph scenario describing life in that disease state. These subjects were then asked to rate the quality of life that they would assign to survival in that disease state.

Cost data

Costs, not charges, were used to compute cost effectiveness in this model. Cost data were derived from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services of the US government (formerly the Health Care Financing Administration) and from published data (http://www.cms.hhs.gov/providers/pufdownload/carrpuf.asp). Diagnosis related group data and current procedure terminology codes were used to calculate inpatient resource utilisation while outpatient costs were calculated using ambulatory payment classification and current procedure terminology codes. All costs are from the perspective of a third party payer. Only direct health care costs (medical costs incurred to produce the services necessary to care for the patient) were included. Indirect costs, such as lost income from work absence, and direct non-health care costs (non-medical costs associated with health care encounters) were not included in the model. Costs estimates, along with a range of costs used for sensitivity analysis, are listed in table 2 ▶. Costs and outcomes were discounted at an annual rate of 3%.

Table 2.

Model cost estimates

| Variable | Value ($ (€)) | Range ($ (€)) | Reference |

| Completed ablation therapy | 20 000 (16 400) | 10 000–30 000 (8200–24 600) | 30,77* |

| Endoscopy with biopsies | 830 (681) | 350–1200 (287–984) | 30,34,77* |

| Repair of oesophageal perforation | 19 000 (15 580) | 10 000–40 000 (8200–32 800) | 30,77* |

| Endoscopic palliation of unresectable cancer | 2000 (1640) | 1000–5000 (820–4100) | 30,77 |

| Surgical oesophagectomy | 19 000 (15 580) | 10 000–40 000 (8200–32 800) | 30,34,77* |

| Care of incurable cancer | 34 000 (27 880) | 10 000–50 000 (8200–41 000) | 30,77* |

| Clinic visit | 50 (41) | 25–100 (21–82) | 30,77* |

| Total care of ablation related stricture | 2490 (2042) | 900–3000 (738–2460) | 30,77* |

*Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, US government (formerly the Health Care Financing Administration), 2001.

RESULTS

In our baseline scenario, 50 year old subjects who receive no preventative strategy for their BO with HGD live, on average, 13.90 discounted quality adjusted life years (dQALYs) and accrue costs of $748 (€613) per patient. Endoscopic ablation was the most effective strategy, yielding 15.5 dQALYs compared with 15.0 for endoscopic surveillance and 14.9 for oesophagectomy. The average cost effectiveness, which represents the lifetime cost of a given strategy divided by the average life expectancy, was least if one pursued no preventative strategy. Among the active strategies, endoscopic surveillance was the strategy associated with the lowest average cost per dQALY, yielding a cost of $2321 per dQALY (€1903/dQALY). Endoscopic surveillance also dominated surgical oesophagectomy, being both less costly and more effective. No preventative strategy led to almost 20% of the patient population developing oesophageal adenocarcinoma. The lifetime incidence of adenocarcinoma was cut markedly by all three preventative strategies, with oesophagectomy providing the least risk of cancer. Table 3 ▶ shows the results of the base case analysis.

Table 3.

Base case analysis

| Strategy | Cost ($ (€)) | Incremental cost ($ (€)) | Effectiveness (dQALY) | Incremental effectiveness (dQALY) | Average cost effectiveness ($/dQALY (€/dQALY)) | ICER ($/dQALY (€/dQALY)) | Cancers(/1000 patients) |

| No preventative strategy | 748 (613) | — | 13.90 | — | 54 (44) | — | 185.4 |

| Oesophagectomy | 34 857 (28 583) | 34 109 (27 969) | 14.89 | 0.99 | 2341 (1920) | Dominated by surveillance | 2.0 |

| Endoscopic surveillance | 34 724 (28 474) | −133 (−109) | 14.96 | 1.06 | 2322 (1904) | 32 053 (26 283) (extended dominance) | 65.2 |

| Endoscopic ablation | 41 998 (34 438) | 7274 (5965) | 15.51 | 0.55 | 2708 (2220) | 25 621 (21 009) | 31.6 |

Cost, total cost of the strategy over the lifetime of the patient.

Incremental cost, increased cost the strategy represents over the next least costly strategy over the lifetime of the patient.

Effectiveness, total life expectancy remaining for the patient if treated with that strategy, measured in discounted quality adjusted life years (dQALY).

Incremental effectiveness, increased effectiveness the strategy represents over the next least effective strategy.

Incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER), incremental cost divided by the incremental benefit. Represents the additional cost associated with “buying” an additional quality adjusted life year when moving from one less effective strategy to a more effective one.

Cancers per 1000 patients, number of cancers suffered by 1000 theoretical patients if that strategy was pursued.

When comparing the strategy of endoscopic surveillance to that of endoscopic ablation, the model demonstrated that endoscopic ablation was superior to endoscopic surveillance in a relationship known as “extended dominance”.32 In extended dominance, although one strategy is more expensive than another, the prolonged life expectancy associated with the more expensive strategy actually makes it cheaper to buy a quality adjusted life year of additional survival using the more expensive strategy than the less expensive one. In our situation, the incremental cost effectiveness ratio (that is, the cost to buy an extra dQALY), when one utilises endoscopic surveillance instead of no preventative strategy, is approximately $32 000 (€26 240) while the cost when one uses endoscopic ablation instead of no preventative strategy is only about $25 600 (€20 992). Therefore, even though ablative therapy is more expensive per patient, it has the highest return in life years per dollar and is therefore the preferred strategy.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analysis allows for systematic variation of an estimate in the model such that the results of the analysis can be seen over a wide variety of values for any estimate. This technique is especially useful in instances when an important estimate is either poorly described in the literature or has widely divergent estimates. One way sensitivity analysis refers to varying the value of one variable over a range to see the effect of that variable on the cost effectiveness of the strategies. Two way sensitivity analysis refers to the simultaneous variation of two variables.

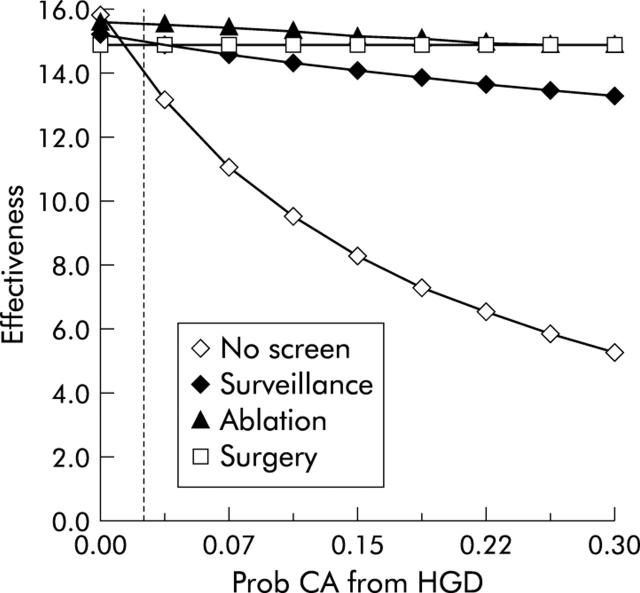

We performed one way sensitivity analysis on key variables included in the model, varying estimates by the ranges noted in table 1 ▶. Several observations are of note. Firstly, the model is sensitive to variation in the rate at which HGD progresses to cancer (fig 5 ▶). As expected, when the risk of developing cancer in HGD increases, doing no prevention becomes a much less effective strategy. Also of note is a change in the relationship of surgery to endoscopic surveillance as cancer risk increases. In our base case, surveillance endoscopy dominates surgical oesophagectomy, being both less costly and more effective. However, as the yearly rate of cancer in the setting of HGD rises, this relationship changes, such that surgery becomes a more cost effective strategy. Are there any conditions in which surgery is more effective than endoscopic ablation? It is not until the yearly risk of cancer in the setting of HGD exceeds 30% (a level which is unrealistically high based on the majority of the published literature) that surgery provides a greater life expectancy than endoscopic ablation.

Figure 5.

One way sensitivity analysis of effectiveness versus the probability (Prob) that high grade dysplasia (HGD) turns into cancer (CA). The yearly probability that Barrett’s oesophagus with HGD develops into cancer is on the X axis, and the effectiveness of the given strategies, measured in discounted quality adjusted life years, is on the Y axis. As the annual likelihood of cancer rises, the effectiveness of the no preventative strategy plummets. The effect on the surgical strategy is negligible as all subjects undergo initial oesophagectomy. It is not until the yearly risk of cancer tops 30%, an unrealistically high estimate, that surgery becomes the most effective strategy.

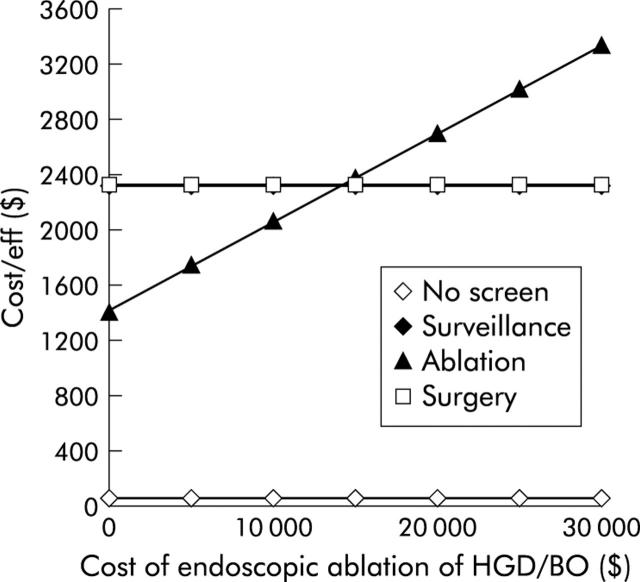

How inexpensive does ablative therapy need to be to supply the best average cost effectiveness of the three active strategies? Figure 6 ▶ demonstrates the cost effectiveness of the strategies as the cost of ablation is varied. The total costs of ablative therapy must be less than $15 000 (€12 300) for ablative therapy to surpass endoscopic surveillance and yield the best average cost effectiveness of the active strategies.

Figure 6.

One way sensitivity analysis of cost of ablative therapy versus average cost effectiveness. As the cost of ablative therapy declines, it becomes the strategy yielding the best average cost effectiveness. When total costs (including drug costs, procedure costs, and follow up endoscopic examinations in the immediate post ablation period) are less than $15 000, the average cost effectiveness of ablation is superior to all other active strategies. BO, Barrett’s oesophagus; HGD, high grade dysplasia.

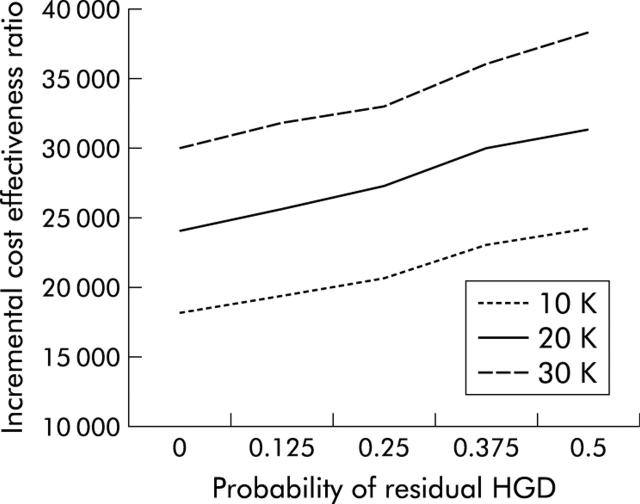

Most other techniques for endoscopic ablative therapy are less expensive than PDT. However, some of these may also be less effective in the eradication of HGD. We performed a two way sensitivity analysis simultaneously varying both the cost and effectiveness of ablative therapy in obliterating HGD. The results are shown in fig 7 ▶. Even under very unfavourable conditions, with ablative therapy being quite expensive and not very effective, the cost effectiveness of ablation as a strategy still remains favourable. Even when ablation costs $30 000 (€24 600), and 50% of cases have residual HGD after ablation, the incremental cost effectiveness of endoscopic ablation compared with no preventative strategy remains under $40 000 (€32 800). Healthcare measures associated with ICERs of less than $50 000 (€41 000) are generally considered cost effective.33

Figure 7.

Two way sensitivity analysis of incremental cost effectiveness versus the probability of residual high grade dysplasia (HGD) for three different costs of ablative therapy. The probability that ablative therapy leaves residual HGD is on the X axis. The incremental cost effectiveness ratio, which is the cost to buy an additional year of discounted quality adjusted life expectancy when changing from no preventative strategy to endoscopic ablative therapy, is on the Y axis. Each line represents a different total cost of ablative therapy. Even when ablative therapy is very costly (that is, $30 000) and relatively ineffective (that is, 50% of those receiving therapy still have residual HGD), the cost of an additional year of life expectancy is relatively inexpensive (under $40 000). In situations where ablative therapy may be both less costly but also less effective (as may be the case with ablative modalities other than photodynamic therapy), cost effectiveness ratios remain very favourable, at less than $25 000.

In addition to standard expected value analysis of the model, we performed a Monte Carlo simulation of the model. This analysis, which simulated a randomised controlled trial enrolling 1000 patients, demonstrated that in greater than 95% of simulations, the incremental cost effectiveness ratio of ablative therapy had an ICER of less than $50 000 (€41 000) when compared with no screening or surveillance.

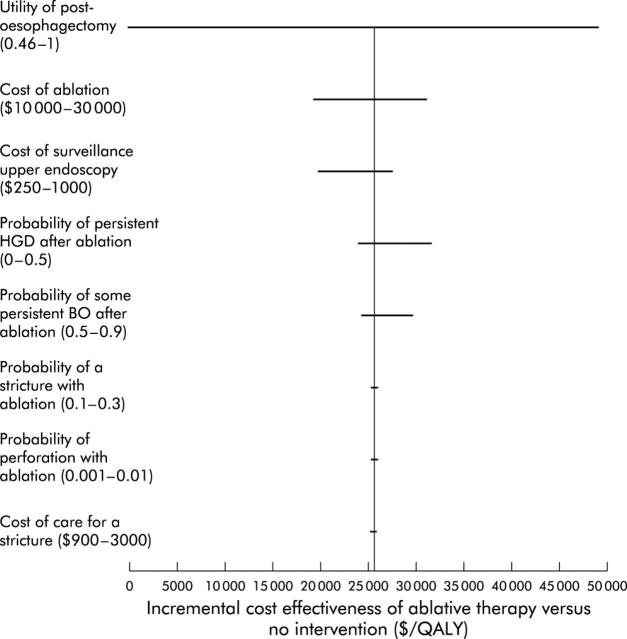

Finally, we performed a “tornado analysis” of key and poorly understood variables in the model. “Tornado analysis” is a way to visually describe how variation in any one input over a clinically relevant range impacts the cost effectiveness of the entire model. In such an analysis, the variability in the incremental cost effectiveness ratio is demonstrated on the X axis, and the key variables assessed are listed on the Y axis. Figure 8 ▶ demonstrates the results of this analysis. As shown, the variable to which the model was most sensitive was the utility of living in the post-oesophagectomy state. Other key variables, such as the probability of stricture formation or the likelihood of residual HGD, have a lesser effect on the model.

Figure 8.

“Tornado diagram” displaying changes in incremental cost effectiveness over a range of plausible values for key variables. This figure demonstrates the changes in the incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) of ablative therapy versus no intervention as multiple key inputs are varied. Input variables are listed on the Y axis, along with the clinically plausible ranges over which they were varied. The bars represent the range in reported ICER for that range of the input variable. Items near the “top” of the tornado (that is, utility of the post-oesophagectomy state and cost of ablation) have a greater impact on the performance of the model than those at the “bottom” of the tornado (that is, probability of perforation and cost of care of a stricture). HGD, high grade dysplasia; QALY, quality adjusted life years.

DISCUSSION

Our model suggests that endoscopic ablative therapy provides a longer quality adjusted life expectancy than either endoscopic surveillance or elective oesophagectomy for those with BO and HGD. Ablative therapy avoids the large upfront costs and considerable morbidity and mortality of surgery. Additionally, unlike endoscopic surveillance, it prevents at least some portion of those destined to develop cancer from progressing to this costly state. Even if ablative therapy is much less effective than has been reported in averting cancer, the incremental cost effectiveness of this strategy still remains well below $50 000 (€41 000) per quality adjusted life year saved.

Although endoscopic surveillance was less expensive than ablative therapy, it was also less effective. Because an additional life year gained with endoscopic ablative therapy is less expensive than a life year gained with endoscopic surveillance, the model suggests that ablative therapy should be the strategy of choice for most payers. This is especially true when one considers that the model mandates continued surveillance endoscopy for all subjects who undergo ablation, whether or not it is successful. Continued endoscopic surveillance in the ablation arm adds additional costs and biases the model against ablation. The model was constructed in this fashion to replicate current practice among those performing ablation but further data may suggest that those who undergo successful ablation do not require continued surveillance. The model was further biased against endoscopic ablative therapy by assuming that all surgical oesophagectomies were done in high volume proficient medical centres. Recent data suggest that results in smaller lower volume centres are much less favourable.25–27

The presence of extended dominance of endoscopic ablation over endoscopic surveillance has interesting ethical implications. If a payer has limited resources, is it better to give a select few subjects a more effective therapy (that is, ablative therapy) or a larger number of patients a less effective therapy (that is, endoscopic surveillance)? In this case, from a utilitarian perspective, it would be logical to give the smaller number of subjects the more effective therapy as the overall life years gained per dollar spent is maximised with this strategy. However, such rationing of healthcare is neither palatable nor egalitarian. As healthcare dollars are not limitless, and expensive therapies for many diseases continue to proliferate, decisions such as which strategy to use in BO with HGD will need to be considered in the larger perspective of society’s willingness to pay for such treatments.

This model has several important strengths. Unlike previous decision analysis models of BO, this model allows for histological misdiagnosis of specimens.30,34–36 Several studies have recently demonstrated that there is substantial variability in the diagnosis of BO histology.22–24 Also, the model features utility estimates derived from actual subjects with BO who are at risk of cancer, which were used for the sensitivity analyses. This is superior to previous models which rely on consensus of experts in the field for some estimates. It is well demonstrated that physician estimates of quality of life and preferences for survival in diminished states often correlate poorly with patient preferences.37–40 Finally, the model does not assume a linear progression through states of dysplasia to cancer. Subjects may progress from no dysplasia to cancer, or may in fact regress to lesser states of dysplasia, as is seen in real world situations.

Important limitations of this model should also be recognised. Several of the estimates used to construct the model were based on relatively short term data. This is especially true of the outcomes of PDT, for which only relatively short term data are available. Extrapolating these data to longer horizons may introduce inaccuracies in the model. Also, there is variability in the reported rates of multiple variables in the model. While we have attempted to assess the effects of this variability on the model by means of sensitivity analysis, the possibility remains that if multiple estimates are extremely inaccurate, the model results may be inaccurate. Next, our model concentrates on Caucasian males, the group most likely to develop adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus. Whether the results are generalisable to other patient populations is unclear. Also, our utilities were in part based on assessments from US veterans with BO, using a visual analogue scale. The applicability of these utilities to other populations is unclear. Finally, the model assumes that the natural history of any given lesion will be the same regardless of previous treatment. For instance, those with HGD are assumed to have the same yearly risk of cancer whether they were assigned directly to the endoscopic surveillance arm or whether they initially underwent unsuccessful PDT and were then placed in the surveillance arm for their HGD after PDT failed. While this assumption is pragmatically essential to create the model, the accuracy of this assumption is not clear.

Perhaps the least well understood parameter in this study is the rate at which HGD progresses to cancer. Some studies have reported that one half or more of those patients undergoing oesophagectomy for HGD will subsequently be found to have carcinoma on the resection specimen.15 It is important to note that such surgical studies actually incorporate two sources of potential initial underdiagnosis of cancer—there is a sampling error inherent in random biopsies as well as a possibility of true progression of the lesion to cancer in the time between endoscopy and resection. In our model, we divided out the high risk of subsequent cancer in HGD using two variables. Firstly, we allowed for a generous sampling error rate, permitting as many as 20% of true cancers to be “missed” at random biopsies and therefore classified as lesser forms of dysplasia. Secondly, we also modelled true progression of the lesion. While our baseline rate of cancer progression was 2.5%, in sensitivity analyses we allowed that rate to range as high as 30% per cycle. Of note, we used data from a medical series8 showing a lower rate of progression from HGD to cancer than most of the surgical resection series. We chose to model these data in our base case because they represented the longest term data available on the largest cohort of HGD assembled, and because the investigators were compulsive about excluding prevalent cancers in their analysis.

A recent model assessing the potential effects of chemoprevention in BO with HGD arrived at similar conclusions to the present study.36 The authors found that chemoprevention with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for BO with HGD would likely be highly cost effective, if we assume that the preventative effects for cancer seen in epidemiological studies of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug users would be transmitted to those with BO. They concluded that any manoeuvre that would result in reduction of cancer occurrence in a group of high risk patients would likely be superior to a strategy that relies on early detection of developing cancers. The same phenomenon is noted in our study, whereby patients receiving ablative therapy achieved an improved life expectancy at a modest cost increase when compared with endoscopic surveillance. The take home message is that interventions that can potentially decrease cancer incidence, even if expensive, will be likely be cost effective compared with strategies that rely on decreasing mortality from treatment of cancer that has already developed.

In summary, our model suggests that endoscopic ablative therapy provides the longest quality adjusted life expectancy in subjects with BO and HGD. Endoscopic surveillance has a lower cost than endoscopic ablation but a condition of extended dominance exists such that endoscopic ablation will likely be the therapy of choice for most payers. Surgery is dominated by endoscopic surveillance in the base case model, and only becomes the favoured strategy at extremely high rates of progression from HGD to cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Deborah Fisher, MD, MHS, who provided utilities used for sensitivity analysis from her work at the Durham VA Medical Center. This work was supported by NIH K23DK59311-01 (Shaheen), the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service grant IIR 99-238-2 (Inadomi), and a grant from Janssen Pharmaceutica.

Abbreviations

BO, Barrett’s oesophagus

HGD, high grade dysplasia

dQALYs, discounted quality adjusted life years

PDT, photodynamic therapy

ICER, incremental cost effectiveness ratio

Conflict of interest: Dr Bergein Overholt receives clinical research support from Axcan Pharma, Inc., a producer of porfimer sodium, a compound commonly used in photodynamic therapy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cameron AJ, Ott BJ, Payne WS. The incidence of adenocarcinoma in columnar-lined (Barrett’s) esophagus. N Engl J Med 1985;313:857–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drewitz DJ, Sampliner RE, Garewal HS. The incidence of adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus: a prospective study of 170 patients followed 4.8 years. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:212–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spechler SJ, Lee E, Ahnen D, et al. Long-term outcome of medical and surgical therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease: follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285:2331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Connor JB, Falk GW, Richter JE. The incidence of adenocarcinoma and dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: report on the Cleveland Clinic Barrett’s Esophagus Registry. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:2037–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaheen NJ, Crosby MA, Bozymski EM, et al. Is there publication bias in the reporting of cancer risk in Barrett’s esophagus? Gastroenterology 2000;119:333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid BJ, Levine DS, Longton G, et al. Predictors of progression to cancer in Barrett’s esophagus: baseline histology and flow cytometry identify low- and high-risk patient subsets. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:1669–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid BJ, Blount PL, Rubin CE, et al. Flow-cytometric and histological progression to malignancy in Barrett’s esophagus: prospective endoscopic surveillance of a cohort. Gastroenterology 1992;102:1212–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnell TG, Sontag SJ, Chejfec G, et al. Longterm nonsurgical management of Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia. Gastroenterology 2001;120:1607–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weston AP, Sharma P, Topalovski M, et al. Long-term follow-up of Barrett’s high-grade dysplasia. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:1888–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miros M , Kerlin P, Walker N. Only patients with dysplasia progress to adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 1991;32:1441–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falk GW, Rice TW, Goldblum JR, et al. Jumbo biopsy forceps protocol still misses unsuspected cancer in Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;49:170–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid BJ, Blount PL, Feng Z, et al. Optimizing endoscopic biopsy detection of early cancers in Barrett’s high-grade dysplasia. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:3089–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heitmiller RF, Redmond M, Hamilton SR. Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia. An indication for prophylactic esophagectomy. Ann Surg 1996;224:66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nigro JJ, Hagen JA, DeMeester TR, et al. Occult esophageal adenocarcinoma: extent of disease and implications for effective therapy. Ann Surg 1999;230:433–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pera M , Trastek VF, Carpenter HA, et al. Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia: an indication for esophagectomy? Ann Thorac Surg 1992;54:199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Overholt BF, Panjehpour M, Haydek JM. Photodynamic therapy for Barrett’s esophagus: follow-up in 100 patients. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;49:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sampliner RE, Fennerty B, Garewal HS. Reversal of Barrett’s esophagus with acid suppression and multipolar electrocoagulation: preliminary results. Gastrointest Endosc 1996;44:532–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma P . An update on strategies for eradication of Barrett’s mucosa. Am J Med 2001;111 (suppl 8A) :147–52S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Overholt BF, Panjehpour M, Halberg DL. Photodynamic therapy for Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia and/or early stage carcinoma: Long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;58:183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devesa SS, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF jr. Changing patterns in the incidence of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer 1998;83:2049–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blot WJ, Devesa SS, Kneller RW, et al. Rising incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. JAMA 1991;265:1287–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ormsby AH, Petras RE, Henricks WH, et al. Observer variation in the diagnosis of superficial oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Gut 2002;51:671–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montgomery E , Bronner MP, Goldblum JR, et al. Reproducibility of the diagnosis of dysplasia in Barrett esophagus: a reaffirmation. Hum Pathol 2001;32:368–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alikhan M , Rex D, Khan A, et al. Variable pathologic interpretation of columnar lined esophagus by general pathologists in community practice. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;50:23–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1128–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finlayson EV, Goodney PP, Birkmeyer JD. Hospital volume and operative mortality in cancer surgery: a national study. Arch Surg 2003;138:721–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urbach DR, Bell CM, Austin PC. Differences in operative mortality between high- and low-volume hospitals in Ontario for 5 major surgical procedures: estimating the number of lives potentially saved through regionalization. Can Med Assoc J 2003;168:1409–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernandez LJ, Jacobson JW, Harris MS. Comparison among the perforation rates of Maloney, balloon, and savary dilation of esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc 2000;51:460–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inadomi JM, Sampliner R, Lagergren J, et al. Screening and surveillance for Barrett esophagus in high-risk groups: a cost-utility analysis. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:176–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Provenzale D , Schmitt C, Wong JB. Barrett’s esophagus: a new look at surveillance based on emerging estimates of cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:2043–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Boer AG, Stalmeier PF, Sprangers MA, et al. Transhiatal vs extended transthoracic resection in oesophageal carcinoma: patients’ utilities and treatment preferences. Br J Cancer 2002;86:851–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cantor SB. Cost-effectiveness analysis, extended dominance, and ethics: a quantitative assessment. Med Decis Making 1994;14:259–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winkelmayer WC, Weinstein MC, Mittleman MA, et al. Health economic evaluations: the special case of end-stage renal disease treatment. Med Decis Making 2002;22:417–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soni A , Sampliner RE, Sonnenberg A. Screening for high-grade dysplasia in gastroesophageal reflux disease: is it cost-effective? Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:2086–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sonnenberg A , Soni A, Sampliner RE. Medical decision analysis of endoscopic surveillance of Barrett’s oesophagus to prevent oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonnenberg A , Fennerty MB. Medical decision analysis of chemoprevention against esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 2003;124:1758–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Donnell H , Phillips RS, Wenger N, et al. Preferences for cardiopulmonary resuscitation among patients 80 years or older: the views of patients and their physicians. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2003;4:139–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hendriks MG, Schouten HC. Quality of life after stem cell transplantation: a patient, partner and physician perspective. Eur J Intern Med 2002;13:52–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCammon KA, Kolm P, Main B, et al. Comparative quality-of-life analysis after radical prostatectomy or external beam radiation for localized prostate cancer. Urology 1999;54:509–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haidet P , Hamel MB, Davis RB, et al. Outcomes, preferences for resuscitation, and physician-patient communication among patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Am J Med 1998;105:222–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma P , Reker D, Falk G, et al. Progression of Barrett’s esophagus to high-grade dysplasia and cancer: Preliminary results of the BEST (Barrett’s Esophagus Study) trial. Gastroenterology 2001;120:A16. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hameeteman W , Tytgat GN, Houthoff HJ, et al. Barrett’s esophagus: development of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 1989;96:1249–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robertson CS, Mayberry JF, Nicholson DA, et al. Value of endoscopic surveillance in the detection of neoplastic change in Barrett’s oesophagus. Br J Surg 1988;75:760–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma P , Morales TG, Bhattacharyya A, et al. Dysplasia in short-segment Barrett’s esophagus: a prospective 3-year follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:2012–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weston AP, Badr AS, Hassanein RS. Prospective multivariate analysis of clinical, endoscopic, and histological factors predictive of the development of Barrett’s multifocal high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:3413–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schoenfeld P , Johnston M, Piorkowski M, et al. Effectiveness and patient satisfaction with nurse-directed treatment of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:906–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weston AP, Badr AS, Hassanein RS. Prospective multivariate analysis of clinical, endoscopic, and histological factors predictive of the development of Barrett’s multifocal high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:3413–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katz D , Rothstein R, Schned A, et al. The development of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma during endoscopic surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:536–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spechler SJ, Robbins AH, Rubins HB, et al. Adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s esophagus. An overrated risk? Gastroenterology 1984;87:927–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weston AP, Badr AS, Hassanein RS. Prospective multivariate analysis of factors predictive of complete regression of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:3420–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolfsen HC, Woodward TA, Raimondo M. Photodynamic therapy for dysplastic Barrett esophagus and early esophageal adenocarcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc 2002;77:1176–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.May A , Gossner L, Pech O, et al. Intraepithelial high-grade neoplasia and early adenocarcinoma in short-segment Barrett’s esophagus (SSBE): curative treatment using local endoscopic treatment techniques. Endoscopy 2002;34:604–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ackroyd R , Kelty CJ, Brown NJ, et al. Eradication of dysplastic Barrett’s oesophagus using photodynamic therapy: long-term follow-up. Endoscopy 2003;35:496–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ackroyd R , Brown NJ, Davis MF, et al. Photodynamic therapy for dysplastic Barrett’s oesophagus: a prospective, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. Gut 2000;47:612–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barr H , Shepherd NA, Dix A, et al. Eradication of high-grade dysplasia in columnar-lined (Barrett’s) oesophagus by photodynamic therapy with endogenously generated protoporphyrin IX. Lancet 1996;348:584–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Winters C jr, Spurling TJ, Chobanian SJ, et al. Barrett’s esophagus. A prevalent, occult complication of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 1987;92:118–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Streitz JMJ, Andrews CWJ, Ellis FH jr. Endoscopic surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Does it help? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1993;105:383–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Corley DA, Levin TR, Habel LA, et al. Surveillance and survival in Barrett’s adenocarcinomas: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 2002;122:633–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Menke-Pluymers MB, Schoute NW, Mulder AH, et al. Outcome of surgical treatment of adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 1992;33:1454–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ellis FH Jr, Gibb SP, Watkins E Jr. Esophagogastrectomy. A safe, widely applicable, and expeditious form of palliation for patients with carcinoma of the esophagus and cardia. Ann Surg 1983;198:531–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ellis FH jr, Heatley GJ, Krasna MJ, et al. Esophagogastrectomy for carcinoma of the esophagus and cardia: a comparison of findings and results after standard resection in three consecutive eight-year intervals with improved staging criteria. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1997;113:836–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Skinner DB. En bloc resection for neoplasms of the esophagus and cardia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1983;85:59–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nguyen NT, Luketich JD, Friedman DM, et al. Pulmonary embolism following laparoscopic antireflux surgery: a case report and review of the literature. JSLS 1999;3:149–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bonavina L , Incarbone R, Saino G, et al. Clinical outcome and survival after esophagectomy for carcinoma in elderly patients. Dis Esophagus 2003;16:90–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rentz J , Bull D, Harpole D, et al. Transthoracic versus transhiatal esophagectomy: a prospective study of 945 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003;125:1114–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wong AC, Law S, Wong J. Influence of the route of reconstruction on morbidity, mortality and local recurrence after esophagectomy for cancer. Dig Surg 2003;20:209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dimick JB, Pronovost PJ, Cowan JA, et al. Complications and costs after high-risk surgery: where should we focus quality improvement initiatives? J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:671–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peters JH, Clark GW, Ireland AP, et al. Outcome of adenocarcinoma arising in Barrett’s esophagus in endoscopically surveyed and nonsurveyed patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1994;108:813–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chan MF. Complications of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 1996;6:287–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kavic SM, Basson MD. Complications of endoscopy. Am J Surg 2001;181:319–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arrowsmith JB, Gerstman BB, Fleischer DE, et al. Results from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy/U.S. Food and Drug Administration collaborative study on complication rates and drug use during gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 1991;37:421–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hart R , Classen M. Complications of diagnostic gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy 1990;22:229–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iannettoni MD, Vlessis AA, Whyte RI, et al. Functional outcome after surgical treatment of esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg 1997;64:1606–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Adamek HE, Jakobs R, Dorlars D, et al. Management of esophageal perforations after therapeutic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32:411–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ballesta-Lopez C , Vallet-Fernandez J, Catarci M, et al. Iatrogenic perforations of the esophagus. Int Surg 1993;78:28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moghissi K , Pender D. Instrumental perforations of the oesophagus and their management. Thorax 1988;43:642–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Provenzale D , Kemp JA, Arora S, et al. A guide for surveillance of patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:670–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]