Abstract

Background: Distinguishing hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) from non-hereditary colorectal cancer (CRC) can increase the life expectancy of HNPCC patients and their close relatives.

Aim: To determine the effectiveness, efficiency, and feasibility of a new strategy for the detection of HNPCC, using simple criteria for microsatellite instability (MSI) analysis of newly detected tumours that can be applied by pathologists. Criteria for MSI analysis are: (1) CRC before age 50 years; (2) second CRC; (3) CRC and HNPCC associated cancer; or (4) adenoma before age 40 years.

Methods: The efficacy and cost effectiveness of the new strategy was evaluated against current practice. Decision analytic models were constructed to estimate the number of extra HNPCC mutation carriers and the costs of this strategy. The incremental costs and gain in life expectancy for a HNPCC mutation carrier were evaluated by Markov modelling. Feasibility was explored in five hospitals.

Results: Using the new strategy, 2.2 times more HNPCC patients can be identified among a CRC population compared with current practice. This new strategy was found to be cost effective with an expected cost effectiveness ratio of €3801 per life year gained. When including the group of siblings and children, the cost effectiveness ratio became €2184 per life year gained. Sensitivity analysis showed these findings to be robust.

Conclusions: MSI testing in a selection of newly diagnosed CRC patients was shown to be cost effective and a feasible method to identify patients at risk for HNPCC who are not recognised by family history.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, HNPCC, microsatellite instability, cost effectiveness, genetic testing

Identification of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) from non-hereditary colorectal cancer (CRC) leads to more effective surveillance, and subsequently can prevent premature death of HNPCC patients and close relatives. HNPCC is the most common hereditary form of colorectal carcinoma and is estimated to account for up to 5% of all CRC (CRC) patients.1 Identification of HNPCC is based on family history.2,3 The clinical criteria of HNPCC, the Amsterdam II criteria, are limited in sensitivity and rely on patients’ recall of family cancer history.4 Identification based on family history is inexpensive. However, due to small families and unawareness of family history only a proportion of the expected number of HNPCC patients in a CRC population is identified by family history.5–7

In most families, HNPCC is caused by a defect in one of the mismatch repair (MMR) genes: MLH1 or MSH2 and, rarely, MSH6 or PMS2.8 Subjects carrying the mutation have a very high risk of developing CRC (50–85%), endometrial cancer (20–50%), and an increased risk for several other types of cancer (including carcinomas of stomach, small bowel, biliary tract, central nervous system, sebaceous gland, upper urinary tract, and ovaries; <10%).9–11

Mismatch repair genes play a role in DNA repair. Inactivation of this pathway causes length variations of short repetitive DNA sequences in tumour DNA, called microsatellite instability (MSI). More than 90% of the CRC from patients with a pathogenic MMR gene mutations and 10–15% of sporadic CRC are characterised by MSI.12 According to the high prevalence of MSI in HNPCC associated tumours, testing for MSI can be used as a tool to select patients with a high risk for hereditary CRC. MSI analysis of tumour DNA and mutation analysis of germline DNA are expensive. MSI or DNA analysis should only be applied to those patients at risk for HNPCC.13 The revised Bethesda guidelines (2001) appeared to be a good tool to identify individuals at high risk of HNPCC, especially in groups of patients with a positive family history of CRC.4,12,13 However, the Bethesda Guidelines as well as Amsterdam II Criteria are criticised for being too complex to use in daily clinical practice.13,14

A new strategy for the detection of patients at high risk for HNPCC was developed based on selection of individual patients for MSI analysis with characteristics that are easy to use in clinical practice. This new strategy is an extension to ongoing current practice, with identification based on family history.

Newly detected patients are selected for MSI testing if they fulfil one of the following selection criteria: (1) colorectal cancer diagnosed before the age of 50 years; (2) second CRC; (3) CRC and other associated extracolonic cancer (endometrium, ovarian, gastric, hepatobilliary, small bowel cancer, or transitional-cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis or ureter), or (4) a colorectal adenoma with high grade dysplasia diagnosed before the age of 40 years. An essential difference of the new strategy is that the pathologist can apply these criteria to select patients and tumour specimen for MSI testing. In the case of a positive MSI test result, referral for genetic counselling is suggested concerning the probability of hereditary colorectal cancer, and eventually mutation analysis of MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6. A more effective detection of HNPCC mutation carriers will improve the efficiency of cancer prevention in families with HNPCC, by allowing family members who do not carry the mutated gene to avoid costly and burdensome surveillance.

To evaluate this new strategy against current practice, an economic evaluation was performed using two decision analytical models: one directed to a newly diagnosed CRC patient, and another directed to the siblings and children of an identified HNPCC patient.

METHODS

The incremental cost effectiveness of the new strategy to identify HNPCC patients from non-hereditary patients is compared with the current strategy, following a healthcare perspective. Effectiveness was expressed in life years and costs in Euros (indexed to 2002) using a time horizon of life expectancy. The “base case” cost effectiveness analysis was performed using our most reliable estimates for all model parameters. To study the impact of uncertainty concerning parameters one way sensitivity analyses were performed.15,16

Cost effectiveness model

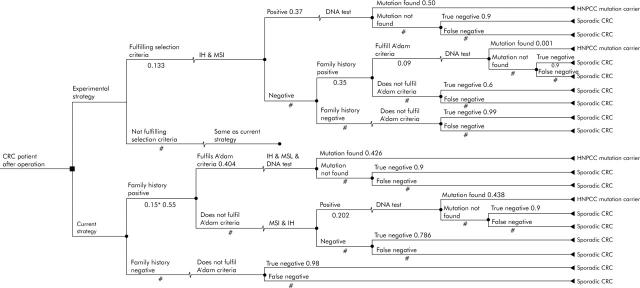

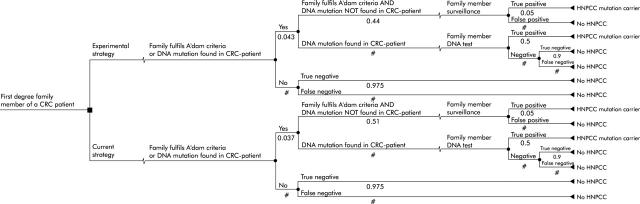

Two decision analytic models were developed that integrated Markov chain analyses using the decision analysis program DATA (TreeAge Software, Inc, Williamstown, MA, USA). The first decision model focused on the incremental cost effectiveness of the new strategy in newly diagnosed patients compared with common practice (fig 1 ▶). This patient based model provided the intermediary outcome “extra MLH1 or MLH2 mutation carriers detected” that was used as input in the second, siblings and children oriented decision model (fig 2 ▶). Siblings and children follow in both arms (strategies) of the decision model the same pattern of healthcare consumption. But the input in both arms differs, because of the extra amount of true positive HNPCC patients detected in the patient based model. Markov chain analyses are added to the decision trees and evaluated the surveillance of a hypothetical cohort of HNPCC patients or their siblings and children.

Figure 1.

Patient based decision model (the figures refer to the probability of the variable; # is the complementary probability (1-p)).

Figure 2.

Family based decision model (the figures refer to the probability of the variable; # is the complementary probability (1-p)).

Data sources and assumptions

It was assumed that 87% of the eligible patients would participate in genetic testing.17 Surveillance was defined as colonoscopy with polypectomy every two years, with the assumption of complete adherence with the surveillance programme. The average age of a HNPCC patient at diagnosis of a CRC was 46 years.18 The age of a first degree family member starting surveillance was 35 years, based on the midpoint age in the range of a child (20 years) and a sibling (50 years) that start surveillance. Parents were not included in this model. For both Markov models, the cancer mortality rate was assumed to be zero after 15 years. Future costs and effects were discounted at 4% to present values.19

Several specific databases (University Medical Centre Nijmegen (UMCN), University Hospital Groningen (AZG), Netherlands Foundation for the Detection of Hereditary Tumours (STOET), Comprehensive Cancer Centres east and south (IKO & IKZ), Dutch Registry of Pathology (PALGA)) were used as input for the decision analytic models (an extensive description of these databases is available upon request).

Where necessary the data were completed with literature and rarely by expert opinions (consensus group of medical experts UMCN and AZG). Table 1 ▶ shows the variables used as input and the data sources used to value them. In literature the probability that a patient with CRC below 50 years or with a double tumour, has a positive MSI result, and carries a deleterious MLH1 or MSH2 germline mutation ranges from 23–78%,20–28 with a mean of 50%. The probability that a patient fulfils the new selection criteria, has a positive MSI result, and carries a deleterious MLH1 or MSH2 germline mutation ranges from 16–63% explored with sensitivity analyses.

Table 1.

| Input for the cost effectiveness models | Data source |

| Probability that a CRC patient: | |

| Satisfies selection criteria | Dutch Cancer Registration |

| Has a positive MSI test result (given selection criteria) | AZG |

| Has a DNA mutation (given MSI positive and given selection criteria) | AZG |

| Satisfies AC (given selection criteria and given MSI test negative) | AZG |

| Has a DNA mutation (given the selection criteria and given a negative MSI test and given AC criteria) | AZG, Literature20–28 |

| Has a positive family history | Literature11 |

| That the family history is taken by medical specialist | UMCN |

| Satisfies AC (given a positive family history) | UMCN |

| Has a DNA mutation (given a positive family history and given AC) | UMCN |

| Has a positive MSI test result (given a positive family history and not satisfying AC) | UMCN |

| Has a DNA mutation (given a positive family history and not satisfying AC and given a positive MSI test result) | UMCN, AZG, Literature20–28 |

| Probabilities that a first degree family member of a CRC patient: | |

| Satisfies the AC or has a CRC family member with positive DNA test result according to the new strategy | Patient model |

| Satisfies the AC or has a CRC family member with positive DNA test result according to the current strategy | Patient model |

| Is tested because the CRC family member has a positive DNA test result | Patient model |

| Satisfies the AC without a verified detected mutation in the CRC family member, has an MLH1 or MSH2 mutation | Literature21,36,40 |

| Has an MLH1 or MSH2 mutation (given the mutation in the CRC patient) | Literature11 |

| Has an MLH1 or MSH2 mutation (not satisfying the AC and without a detected mutation in the CRC family member) | Expert opinion |

| Probability that: | |

| A negative DNA test result is a true negative result | Literature21,36,40; expert opinion |

| A negative MSI test result is a true negative result | Meta-analysis29 |

| Not satisfying AC is true negative | Literature29 |

| Costs | |

| MSI, DNA, counselling by a clinical geneticist, colonoscopy, subtotal colectomy | UMCN |

| Follow up of an HNPCC patient | Patient records |

AZG means empirical data from the University Hospital Groningen, UMCN means empirical data from the University Medical Centre Nijmegen.

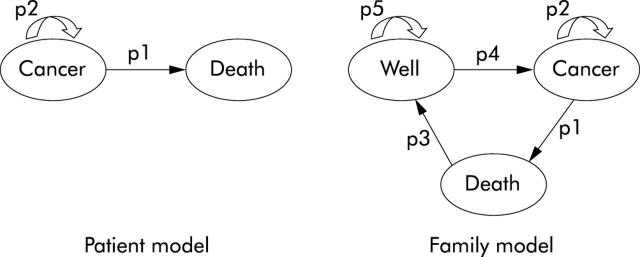

A meta-analysis was performed to estimate specificity values for the Amsterdam criteria and MSI analysis.29 Concerning the Markov chain models (fig 3 ▶), the probabilities to develop CRC for a HNPCC patient who does or does not participate in a surveillance programme were based on the findings of Järvinen et al.30 Data from the Netherlands Foundation for the Detection of Hereditary Tumours (STOET) were used to estimate the probability for a HNPCC patient to die from symptomatic or screened detected CRC. Non-CRC mortality rates were based on age related survival tables supplied by the Central Bureau of Statistics in the Netherlands (Statline).

Figure 3.

Influence diagrams of the Markov parts of both the patient (left) and the family (right) model. p1, probability of dying from symptomatic or screened detected CRC, based on data of the Dutch Hereditary Cancer Registration and the natural mortality rates based on age related survival tables supplied by the Central Bureau of Statistics in the Netherlands (Statline); p2, probability of developing cancer, based on findings of Järvinen et al30; p3, natural mortality rates based on age related survival tables supplied by the Central Bureau of Statistics in the Netherlands (Statline). p4 = 1−p1−p3; p5 = 1−p2.

Costs

Following a healthcare perspective, only direct medical costs were used for analysis. The volumes of care related to treatment and follow up of HNPCC patients were based upon the analysis of 30 records of HNPCC patients diagnosed with CRC (UMCN and AZG). Existing guideline prices for the Netherlands31 were used to value an outpatient visit and a hospital day. A full cost price was calculated based on UMCN information of the year 2002 for all other units of care (that is, MSI analysis, DNA analysis, colonoscopy, counselling, and so on). Overhead costs were according to Dutch guidelines added to the total direct costs.31

Sensitivity analysis

One way sensitivity analyses were performed across a range of assumptions concerning the probabilities: compliance of newly diagnosed CRC patients with the new selection criteria; patients with an MSI positive tumour that had an MLH1 or MSH2 mutation. Furthermore, (MIN-MAX) specificity values for MSI analysis and DNA analysis were evaluated. In addition, the compliance rate with the Amsterdam Criteria was varied and finally the impact of the discount rate on the estimate of the incremental costs per life year gained was evaluated.

RESULTS

Patient based model

Using the new strategy more than twice the number of HNPCC mutation carriers were detected as compared with current practice. In the group of newly diagnosed CRC patients, 3.5% HNPCC patients carrying a mutation were detected with the new strategy, whereas with the current strategy this is 1.6% (table 2 ▶). The new strategy is more expensive (incremental discounted costs €141). This results in an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of €7330 per additional mutation carrier detected (table 2 ▶). This result was extended with a Markov chain analysis which showed an extra 2.5 life years per CRC patient, and found that the surveillance strategy was more expensive (€2249) than the non-surveillance strategy (€322). Integrating the results of the Markov chain analysis with the CRC patient based decision model resulted in an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of €3801 per life year gained (table 2 ▶).

Table 2.

Incremental effects, costs, and cost effectiveness of the new strategy for detection and surveillance of CRC patients and relatives compared with the current strategy (detected for carrying a deleterious mutation that predisposes for HNPCC)

| CRC patients | Children and siblings | |

| Extra HNPCC mutation carriers detected (%) | 1.9 | 1 |

| Incremental screening costs (€) | 141 | 9 |

| Incremental costs/mutation carrier detected (€) | 7330 | 950 |

| Incremental surveillance costs (€) | 1927 | 1675 |

| Life years gained | 2.5 | 3 |

| Incremental costs per life year gained (€) | 3801 | 855 |

Overall incremental costs per life year gained: €2184.

Family based model

With the new strategy, more CRC patients are identified as HNPCC patients, leading to an enhanced number of relatives detected to carry a mutation that predisposes for HNPCC. In a group of children and siblings of newly diagnosed CRC patients, an extra 1% MLH1 or MSH2 mutation carriers will be detected when the new strategy is used, compared with the current strategy (table 2 ▶). The Markov chain analysis for a child or sibling showed that the surveillance strategy was more expensive (€6489) but more effective, with an extra three life years per relative. The incremental cost effectiveness ratio for a child or sibling detected to be a HNPCC mutation carrier is €855 per life year gained. Integrating the results of both the patient and family based model in one efficiency ratio showed that the new strategy provides an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of €2184 per life year gained for CRC patients, their siblings, and their children.

Table 3 ▶ shows the costs per unit of production. The MSI analyses of the new strategy are cost drivers, resulting in extra genetic counselling and DNA analyses for CRC patients, siblings, and children. As a result of the extra mutation carriers detected when implementing the new strategy more colonoscopies were performed at a more regular basis.

Table 3.

Full costs prices of the different units of care used in the cost effectiveness model

| Cost | |

| MSI analysis | €529 |

| DNA analysis for CRC index patient | €1308 |

| DNA analysis for family member from a mutation detected family | €286 |

| Genetic counselling CRC patient, intake visit | €95 |

| Genetic counselling CRC patient, average costs per visit* | €17 |

| Genetic counselling family member, total costs | €54 |

| Colonoscopy | €144 |

| Subtotal colectomy | €6557 |

| Follow up after subtotal colectomy (for 3 years) | €1634 |

*Average of all possible visits to the genetic counsellor.

Sensitivity analysis

The probability that a newly diagnosed CRC patient complies with our selection criteria, as well as the probability that a patient with a MSI positive tumour had an MLH1 or MSH2 mutation, has a considerable effect on the percentage of patients detected with an MLH1 or MSH2 mutation, and consequently on the final outcome. The detection rate of the new strategy for mutation detected HNPCC patients among all newly diagnosed CRC patients varies between 2.1–4.1%; consequently the incremental cost effectiveness ratio varies between €1831–6196 per life year gained for CRC patients, their siblings, and children. These, together with the other results of the sensitivity analyses, are displayed in table 4 ▶.

Table 4.

Results of the sensitivity analysis on HNPCC mutation carriers detected and on incremental costs per life year gained

| % Carriers in new strategy* | Incremental costs/life year gained (€) | |||||

| Variable | Base case | Range | Low | High | Low | High |

| Probability of complying with selection criteria | 0.13 | 0.10–0.20† | 3.4 | 4.9 | 2130 | 2103 |

| Probability mutation is positive given MSI-H | 0.50 | 0.16–0.63‡ | 2.1 | 4.1 | 6196 | 1831 |

| Specificity of the Amsterdam criteria | 0.60 | 0.46–0.68¶ | 3.9 | 3.9 | NE | NE |

| Specificity of MSI analysis | 0.79 | 0.59–0.91¶ | 3.9 | 3.9 | NE | NE |

| Specificity of DNA analysis | 0.90 | 0.9–0.95§ | 3.9 | 3.9 | NE | NE |

| Discount rate costs | 0.04 | 0–0.06 | NE | NE | 2145 | 2106 |

| Discount rate effect | 0.04 | 0–0.06 | NE | NE | 2038 | 2157 |

*The variables had no effect on the outcomes of the current strategy, therefore only the outcomes of the new strategy are presented.

†Based on data from the Comprehensive Cancer Centre East, whereas the range was based on expert opinions.

‡Empirical data varied between16–63%, whereas the data from literature varied between 23–78%.

¶The result of a meta-analysis and the range was based on the lowest and highest value found in literature.

§The base case and the range were both expert opinions.

NE, no effect found.

DISCUSSION

The new strategy for the detection of HNPCC is found to be effective and efficient, as over twice as many HNPCC patients were identified, and has an overall cost effectiveness ratio of €2184 per life year gained. An essential difference of the new strategy is that the pathologist can apply the criteria to select tumour specimens for MSI analysis. An explorative study about the feasibility of this new strategy showed, in four regional and one university hospital, a positive result realising 100% adoption of the new strategy within a few months.

The strength of this study is the use of databases. The results of our cost effectiveness study are in line (although the exact figures differ) with the literature investigating a related hypothesis. Reyes et al studied the cost effectiveness of a mixed strategy focussing on a set of criteria less stringent than the Bethesda criteria: (1) age under 50 years; (2) at least one first degree relative of the proband with CRC or endometrium cancer; (3) previous CRC or endometrium cancer in the proband. This mixed strategy was compared with mutation testing of patients complying with the Amsterdam criteria and shown to be efficient, based on a cost effectiveness ratio of $6500 per extra mutation carrier detected.32 In another study Ramsey et al concluded that a strategy in which all newly diagnosed CRC patients that meet the Bethesda guidelines are tested for MSI analyses was cost effective ($42 210 per life year gained). When considering the benefit for their immediate relatives, cost effectiveness increased to $7556.33 Our results differ considerably in magnitude compared with Ramsey’s. The difference in outcomes can be explained by the fact that Ramsey et al used prophylactic colectomy as the cancer prevention strategy, which is more expensive than surveillance. The price for a colectomy is (according to Ramsey) $30 673, whereas surveillance (in our study) is less than €2000. In our study the price for a subtotal colectomy and follow up for three years is a little over €8000. It is obvious that the choice of follow up strategies is principal with regard to the outcome of the efficiency ratio. Also it should be mentioned that our study was mainly based on databases from a European setting, as opposed to published data from a transatlantic origin (see Methods section). This might have caused the difference in effect between Ramsey et al and us (1.25 life years gained for a CRC patient found by Ramsey v 2.5 life years gained found in the patient model by us). The combination of higher incremental costs and lower incremental effects probably explains the difference in magnitude of the cost effectiveness ratio of Ramsey et al compared with our study.

From other studies, the gains in life expectancy from colonoscopy programmes for relatives is known to range from 7–13 years,34,35 whereas our data showed a life expectancy gain for relatives of three years. However, if more gain in life expectancy is to be expected the new strategy will give further support to our main conclusion on cost effectiveness.

Our findings must be considered within the context of some limiting factors. Firstly, we focus on HNPCC patients with a MLH1 and MSH2 mutation; MSH6 mutation carriers are not considered. The exclusion of MSH6 mutations may not have a large impact, because in the group of CRC patients under 50 years of age, only a small amount of HNPCC patients are expected to carry an MSH6 mutation.36 Additionally, this study does not address surveillance for other HNPCC related carcinomas. In particular, female HNPCC carriers have a lifetime risk up to 40% to develop endometrium cancer.11 Although the effectiveness of surveillance for that type of cancer is not well known, surveillance for endometrium cancer is recommended.37,38

As the new strategy is shown to be cost effective and feasible, we belive it should be implemented in daily practice. Testing for MSI is straightforward, but the consequences can be diverse because many colorectal cancers show MSI without evidence of germline abnormalities. MSI analysis tests for somatic changes in the tumour and not for germline changes. Among patients with MSI in the tumour DNA there will be sporadic cases and inherited cases. MSI analysis selects patients at high risk for HNPCC that need further analysis to determine whether they do or do not have HNPCC. Discussing the complex information of a positive MSI test result needs to be done with great care because it is given at a time when these patients are adjusting to the diagnosis of cancer and not all patients may want to know their genetic risk for cancer.

We did not include immunohistochemistry (a relatively inexpensive method which can identify loss of MLH1, MSH2, or MSH6 protein products39,40) as a screening technique for several reasons. The most important reason is that the variation in interpretation of immunohistochemistry does not yet permit firm conclusions concerning its use in daily practice.

Very recently, in 2004, a newly revised version of the Bethesda criteria was published,41 which are very much inline with our criteria list.

Overall, it can be concluded that the proposed new strategy is more effective and efficient than current practice. It underlines that MSI testing in selected, newly diagnosed colorectal cancer patients may serve as a powerful method to identify patients at risk for HNPCC in cases where they are not recognised by their family history.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a financial grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW).

We are indebted to R Niessen, MD, from the University Hospital Groningen and the Comprehensive Cancer Centre East and South for their valuable input in the cost effectiveness study. We thank the departments of Pathology and Surgery of Jeroen Bosch Hospital Hertogenbosch, Canisius-Wilhelmina Hospital Nijmegen, Catherina Hospital Eindhoven, and Rijnstate Hospital Arnhem for participation in the feasibility study.

Abbreviations

HNPCC, hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer

CRC, colorectal cancer

MMR genes, mismatch repair genes

MSI, microsatellite instability

REFERENCES

- 1.Summerton N . Diagnosing cancer in primary care. Abingdon: Radcliffe, 1999.

- 2.Vasen HF, Mecklin JP, Khan PM, et al. The International Collaborative Group on Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer (ICG-HNPCC). Dis Colon Rectum 1991;34:424–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasen HF, Watson P, Mecklin JP, et al. New clinical criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome) proposed by the International Collaborative group on HNPCC. Gastroenterology 1999;116:1453–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch H . Chapelle de la A. Genetic susceptibility to non-polyposis colorectal cancer. J Med Gen 1999;36:801–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Church J . McGannon E. Family history of colorectal cancer: how often and how accurately is it recorded, Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:1540–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sijmons RH, Boonstra AE, Reefhuis J, et al. Accuracy of family history of cancer: clinical genetic implications. Eur J Hum Genet 2000;8:181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katballe N , Juul S, Christensen M, et al. Patient accuracy of reporting on hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer-related malignancy in family members. Br J Surg 2001;88:1228–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu B , Parsons R, Papadopoulos N, et al. Analysis of mismatch repair genes in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer patients. Nat Med 1996;2:169–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasen HF, Stormorken A, Menko FH, et al. MSH2 mutation carriers are at higher risk of cancer than MLH1 mutation carriers: a study of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer families. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:4074–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watson P , Lynch HT. Extracolonic cancer in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cancer 1993;71:677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch HT, de la Chapelle CA. Hereditary colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;348:919–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boland CR, Thibodeau SN, Hamilton SR, et al. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Microsatellite Instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 1998;58:5248–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Gastroenterology Association. American Gastroenterology Association Medical Position Statement: Hereditary Colorectal Cancer and Genetic Testing. Gastroenterology 2001;121:195–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cravo ML, Fidalgo PO, Lage PA, et al. Validation and simplification of Bethesda guidelines for identifying apparently sporadic forms of colorectal carcinoma with microsatellite instability. Cancer 1999;85:779–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Briggs AH, Wonderling DE, Mooney CZ. “Uncertainty in the economic evaluation of health care technologies: the role of sensitivity analysis. ” Health Econ 1994;3:95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buxton MJ, Drummond MF, Van Hout BA, et al. Modelling in economic evaluation: an unavoidable fact of life. Health Econ 1997;6:217–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner A , Barrows A, Wijnen JT, et al. Molecular analysis of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer in the United States: high mutation detection rate among clinically selected families and characterization of an American founder genomic deletion of the MSH2 gene. Am J Hum Genet 2003;72:1088–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch HT, Chapelle de la A. Genetic susceptibility to non-polyposis colorectal cancer. J Med Genet 1999;36:801–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drummond MF, O’Brien B, Stoddart GL, et al. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- 20.Aaltonen L , Salovaara R, Chapelle de la A. Incidence of HNPCC and the feasibility of molecular screening for disease. N Eng J Med 1998;21:1481–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Pedersen GM. AGA technical review on hereditary colorectal cancer and genetic testing. Gastroenterology 2001;121:198–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salovaara R , Loukola A, Kristo P, et al. Population-based molecular detection of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan TL, Yuen ST, Chung LP, et al. Frequent microsatellite instability and mismatch repair gene mutations in young Chinese patients with colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:1221–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fornasarig M , Viel A, Valentini M, et al. Microsatellite instability and MLH1 and MSH2 germline defects are related to clinicopathological features in sporadic colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep 2000;7:39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho JW, Yuen ST, Chung LP, et al. Distinct clinical features associated with microsatellite instability in colorectal cancers of young patients. Int J Cancer 2000;89:356–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montera M , Resta N, Simone C, et al. Mutational germline analysis of hMSH2 and hMLH1 genes in early onset colorectal cancer patients. J Med Genet 2000;37:7e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terdiman JP, Gum JR Jr, Conrad PG, et al. Efficient detection of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer gene carriers by screening for tumor microsatellite instability before germline genetic testing. Gastroenterology 2001;120:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wahlberg SS, Schmeits J, Thomas G, et al. Evaluation of microsatellite instability and immunohistochemistry for the prediction of germ-line MSH2 and MLH1 mutations in hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer families. Cancer Res 2002;62:3485–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kievit W , Bruin de JHFM, Adang EMM, et al. Current clinical selection strategies for identification of HNPCC families are inadequate: a meta-analysis. Clin Genet 2004;65:308–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Järvinen H , Aarnio M, Mustonen H, et al. Controlled 15-year trial on screening for CRC in families with HNPCC. Gastroenterology 2000;118:829–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oostenbrink JB, Koopmanschap MA, Rutten FFH. Handleiding voor kostenonderzoek, methoden en richtlijnprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. Amstelveen: College voor zorgverzekeringen, 2000.

- 32.Reyes CM, Allen BA, Terdiman JP, et al. Comparison of selection strategies for genetic testing of patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma: effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Cancer 2002;95:1848–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramsey SD, Clarke L, Etzioni R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of microsatellite instability screening as a method for detecting hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:577–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vasen HF, van Ballegooijen M, Buskens E, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of colorectal screening of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma gene carriers. Cancer 1998;82:1632–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Syngal S , Weeks JC, Schrag D, et al. Benefits of colonoscopic surveillance and prophylactic colectomy in patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer mutations. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:787–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peltomaki P . Role of DNA mismatch repair defects in the pathogenesis of human cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1174–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rijcken FE, Mourits MJ, Kleibeuker JH, et al. Gynecologic screening in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2003;91:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dove-Edwin I , Boks D, Goff S, et al. The outcome of endometrial carcinoma surveillance by ultrasound scan in women at risk of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma and familial colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 2002;94:1708–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruszkiewicz A , Bennett G, Moore J, et al. Correlation of mismatch repair genes immunohistochemistry and microsatellite instability status in HNPCC-associated tumours. Pathology 2002;34:541–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wahlberg SS, Schmeits J, Thomas G, et al. Evaluation of microsatellite instability and immunohistochemistry for the prediction of germ-line MSH2 and MLH1 mutations in hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer families. Cancer Res 2002;62:3485–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Unmar A , Risinger JI, Hawk ET, et al. Testing guidelines for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2004;4:153–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]