Abstract

Background and aim: Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric atrophy are both risk factors for gastric cancer. We aimed to elucidate the natural history of gastric cancer development according to H pylori infection and gastric atrophy status.

Subjects and methods: A total of 9293 participants in a mass health appraisal programme were candidates for inclusion in the present prospective cohort study: 6983 subjects revisited the follow up programme. Subjects were classified into four groups according to serological status at initial endoscopy. Group A (n = 3324) had “normal” pepsinogen and were negative for H pylori antibody; group B (n = 2134) had “normal” pepsinogen and were positive for H pylori antibody; group C (n = 1082) had “atrophic” pepsinogen and were positive for H pylori antibody; and group D (n = 443) had “atrophic” pepsinogen and were negative for H pylori antibody. Incidence of gastric cancer was determined by annual endoscopic examination.

Results: Mean duration of follow up was 4.7 years and the average number of endoscopic examinations was 5.1. The annual incidence of gastric cancer was 0.04% (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.02–0.09), 0.06% (0.03–0.13), 0.35% (0.23–0.57), and 0.60% (0.34–1.05) in groups A, B, C, and D, respectively. Hazard ratios compared with group A were 1.1 (95% CI 0.4–3.4), 6.0 (2.4–14.5), and 8.2 (3.2–21.5) in groups B, C, and D, respectively. Age, sex, and “group” significantly served as independent valuables by multivariate analysis.

Conclusions: The combination of serum pepsinogen and anti-H pylori antibody provides a good predictive marker for the development of gastric cancer.

Keywords: gastric cancer, Helicobacter pylori, pepsinogen, endoscopy, screening

The pathogenic role of Helicobacter pylori for gastric cancer has been documented in a large number of epidemiological studies1–5 and basic research investigations.6–9 In earlier epidemiological studies using H pylori antibody as a marker of infection, various risk ratios of H pylori infection for gastric cancer were reported, ranging widely from none to 10 or above.1–3,10–16

Recently, a follow up study by Uemura et al showed that gastric cancer developed only in patients infected with H pylori when using a full set of diagnostic tests for H pylori infection.5 They also reported in the same study that subjects with severe gastric atrophy, corpus predominant gastritis, or intestinal metaplasia were at increased risk for gastric cancer.5

We also confirmed that gastric atrophy status was essential for cancer development in our previous cross sectional study.17 In that study, gastric atrophy was estimated by serum pepsinogen levels, which were determined in serum samples.17 Pepsinogen I and II, the two main precursors of pepsin, are both produced by chief cells and mucous neck cells of the stomach.18,19 Pepsinogen II is also produced by pyloric gland cells. Chief cells are replaced by pyloric glands, leading to a decrease in pepsinogen I as gastric atrophy develops. However, a decrease in pepsinogen II is minimal. Therefore, both low serum pepsinogen I and a low pepsinogen I/II ratio are recognised as serological markers of gastric atrophy.20–22

The combination of serum pepsinogen and H pylori antibody served as a useful marker for the prevalence of gastric cancer in a cross sectional setting.17 This modality is much simpler and less invasive than those using endoscopy, and therefore suitable for a large general population. On the basis of this premise, we conducted the present prospective study in participants in our health check programme without any specific symptoms. We aimed to estimate the incidence rate of gastric cancer in the general population. The role of H pylori infection and gastric atrophy in cancer development was evaluated in terms of these serological markers.

METHODS

Enrolment

Between March 1995 and February 1997, participants in health examination programmes held by Kameda General Hospital and Makuhari Clinic who underwent upper endoscopy were consecutively enrolled. Blood samples were obtained from each subject. Excluding those with gastric cancer, peptic ulcer, or a past history of surgical resection of the stomach, a total of 9293 participants were candidates for inclusion in this study. Some of these subjects were analysed in a previous cross sectional study.17 Proton pump inhibitors or H2 blockers had not been prescribed within one month prior to the examination. None had undergone eradication therapy for H pylori. Patients were encouraged to undergo endoscopic examination annually to check for the development of gastric cancer, and 6983 revisited the programme for follow up endoscopy during the observation period. Data of these participants were analysed in this study.

The protocol was approved by the ethics committees of the respective institutions, and informed consent was obtained from each subject according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Serum H pylori antibody

Serum anti-H pylori antibody was measured using a commercial ELISA kit (GAP-IgG kit; Biomerica Inc., California, USA). Seropositivity for H pylori antibody was defined by optical density values according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sensitivity and specificity for H pylori infection in Japanese were reported to be 95% and 83%, respectively, compared with the results of specific culture.23

Serum pepsinogen level

Serum pepsinogen was measured using a commercial RIA kit (pepsinogen I/II RIA bead kit; Dainabot Co., Tokyo, Japan). Serum pepsinogen status was defined as “atrophic” when the criteria of both serum pepsinogen I level ⩽70 ng/ml and a pepsinogen I/II ratio (serum pepsinogen I (ng/ml)/serum pepsinogen II (ng/ml)) ⩽3.0 were simultaneously fulfilled, as proposed by Miki and colleagues.22 All other cases were classified as “normal”. A sensitivity of 70.5% and specificity of 97.0% for atrophic gastritis compared with histology have been reported in Japan.24 These criteria have been widely applied to mass screening for gastric cancer in Japan.17,22,24

Classification by anti-H pylori antibody and serum pepsinogen status

Subjects were classified into four groups according to serum pepsinogen status and H pylori status antibody at enrolment. Group A had “normal” pepsinogen and were negative for H pylori antibody. Group B had “normal” pepsinogen and were positive for H pylori antibody. Group C had “atrophic” pepsinogen and were positive for H pylori antibody. Group D had “atrophic” pepsinogen and were negative for H pylori antibody.

Endoscopic and clinicopathological examinations

Gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed with electronic panendoscopes (type XQ200 or P230; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), carefully observing the bulbar portion of the duodenum, the entire stomach, and the oesophagus. Experienced endoscopists performed each examination without knowledge of the serological data of the study subjects. Histopathological assessment of gastric cancer was conducted using surgically resected or endoscopically biopsied samples, categorised as intestinal-type or diffuse-type, according to Lauren’s classification.25 Samples were classified as cardiac or non-cardiac in terms of location.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., North Carolina, USA). Differences in mean age were evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s correction. Difference in sex distribution was evaluated by the Kruskal-Wallis test with Bonferroni’s correction. Incidence of gastric cancer was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Independent risk factors for gastric cancer were assessed by Cox proportional hazard regression. A two sided p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of study subjects

Baseline clinical characteristics of the study subjects are summarised in table 1 ▶. Of 6983 subjects, 3324 (47.6%) were categorised as group A, 2134 (30.6%) as group B, 1082 (15.5%) as group C, and 443 (6.3%) as group D. Each subject underwent 5.1 (0.05) sessions of endoscopy during a follow up period of 4.7 (0.04) years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the subgroups classified according to serum pepsinogen and Helicobacter pylori antibody status

| Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | Total | |

| Pepsinogen status | Normal | Normal | Atrophic | Atrophic | |

| H pylori antibody status | − | + | + | − | |

| No of subjects | 3324 | 2134 | 1082 | 443 | 6983 |

| Male | 2260 | 1489 | 713 | 320 | 4782 |

| Female | 1064 | 645 | 369 | 123 | 2201 |

| Age (y) (mean (SD)) | 47.1 (8.1) | 49.2 (8.3) | 52.0 (8.5) | 53.3 (8.8) | 48.9 (8.5) |

| Pepsinogen I (mean (SD)) | 54.3 (23.9) | 73.7 (29.0) | 41.9 (17.3) | 35.7 (19.0) | 57.1 (27.4) |

| Pepsinogen II (mean (SD)) | 10.1 (7.3) | 20.6 (12.1) | 20.3 (6.8) | 17.9 (7.5) | 15.4 (10.3) |

| No of endoscopies* (mean (SD)) | 5.1 (2.0) | 5.1 (2.0) | 5.0 (1.9) | 5.0 (1.9) | 5.1 (2.0) |

| Duration of follow up (y) (mean (SD)) | 4.8 (1.6) | 4.7 (1.7) | 4.7 (1.7) | 4.5 (1.7) | 4.7 (1.7) |

*Number of endoscopic examinations.

Gastric cancer development

Among 6983 subjects analysed, 43 (37 men and six women) developed gastric cancer during the follow up period. The annual incidence rate of gastric cancer development, as calculated by the person-year method, was 0.13% (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.10%–0.18%). Histopathological features of gastric cancer were intestinal in 34 and diffuse in nine cases. Gastric cardia was involved in two cases. All of the cancers were localised within the submucosa except for one invading the muscularis propria (group B). Twenty three cases were treated by endoscopic resection and 20 cases underwent surgical operation. All were alive in August 2004.

Antibody-pepsinogen status and gastric cancer development

Of 43 cases with gastric cancer, seven were from group A, six from group B, 18 from group C, and 12 from group D. The annual incidence rate was 0.04% (95% CI 0.02%–0.09%), 0.06% (0.03%–0.13%), 0.36% (0.23%–0.57%), and 0.60% (0.34%–1.05%) in groups A, B, C, and D, respectively. The cumulative incidence of gastric cancer by Kaplan-Meier analysis is shown in fig 1 ▶, as stratified by group. Groups C and D had a significantly higher incidence of gastric cancer than groups A and B (fig 1 ▶). Histopathological features of gastric cancer are shown in table 2 ▶. Two cases were found in the gastric cardia and the other 41 elsewhere. Both cardiac cancers occurred in group A. In contrast, no association was found between the groups and histopathological differentiation of cancer.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of the proportion of gastric cancer development classified by pepsinogen status and Helicobacter pylori antibody (groups A–D, see text for details). During follow up, gastric cancer developed in seven of 3324 group A patients (0.2%), six of 2134 group B patients (0.3%), 18 of 1082 group C patients (1.7%), and 12 of 443 group D patients (2.7%) (p<0.0001 by log rank test).

Table 2.

Association of subgroups classified according to serum pepsinogen and Helicobacter pylori antibody status

| Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | |

| No of subjects | 3324 | 2134 | 1082 | 443 |

| Gastric cancer | 7 | 6 | 18 | 12 |

| Annual incidence rate (%/y) | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.35 | 0.60 |

| Histopathological features | ||||

| Site* | ||||

| Cardia | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-cardia | 5 | 6 | 18 | 12 |

| Differentiation | ||||

| Intestinal | 5 | 5 | 14 | 10 |

| Diffuse | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

*p = 0.0148 by Kruskal-Wallis test with Bonferroni’s correction.

Risk factors for gastric cancer and establishment of super high risk group

Age, sex, and “group” were revealed to be independent risk factors by the Cox proportional hazard model (table 3 ▶). Hazard ratios (95% CI) compared with group A were 1.1 (0.4–3.4; p = 0.81) in group B, 6.0 (2.4–14.5; p<0.0001) in group C, and 8.2 (3.2–21.5; p<0.0001) in group D.

Table 3.

Hazard ratio assessment adjusted by Cox proportional hazard model

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Group | |||

| A | 1 | ||

| B | 1.1 | 0.4–3.4 | 0.81 |

| C | 6.0 | 2.4–14.5 | <0.0001 |

| D | 8.2 | 3.2–21.5 | <0.0001 |

| Age (y) | |||

| <60 | 1 | ||

| >60 | 5.3 | 2.9–9.9 | <0.0001 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1 | ||

| Male | 3.2 | 1.3–8.2 | 0.01 |

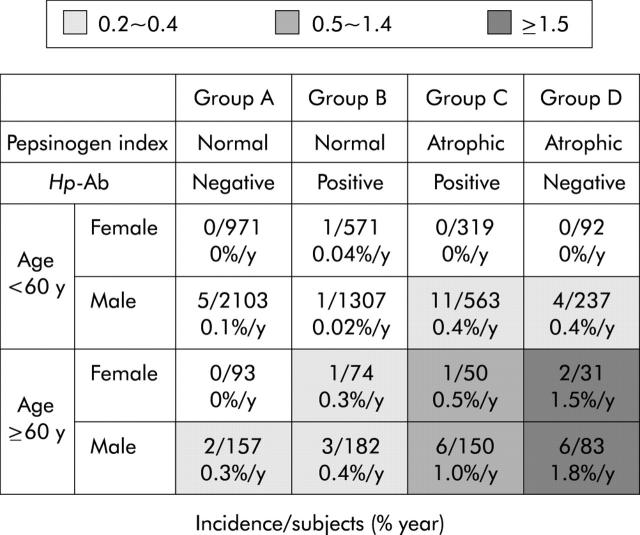

Incidence rates of gastric cancer stratified by age, sex, and “group” are shown in fig 2 ▶. Males older than 60 years in group D showed the highest annual incidence of 1.8% (95% CI 0.81%–3.82%). The incidence rate in the same age group was much lower in groups A and B, being less than 0.5% per year.

Figure 2.

Incidence rates of gastric cancer stratified by age, sex, and serological status. Subjects older than 60 years in group D showed the highest annual incidence of 1.8% in males and 1.5% in females. The incidence rate in the same age group was much lower in groups A and B, being less than 0.5% per year. Hp-Ab, Helicobacter pylori antibody.

DISCUSSION

Gastric cancer is the second (in males) and fourth (in females) lethal cause of malignancy in the world.26 It still remains the most common malignancy in many countries.27H pylori has been established as a definite carcinogen for gastric cancer.28 However, the magnitude of the association in reports has been diverse, especially in Eastern countries suffering high prevalence rates of gastric cancer.10,12–15 Uemura et al claimed from the results of their follow up study that all gastric cancers developed from patients with H pylori infection, and that the risk was highly associated with gastric atrophy status induced by H pylori.5 The result is epoch making and revealing in terms of understanding and preventing gastric carcinogenesis. However, their results were based on hospitalised patients with gastrointestinal diseases, as well as other follow up studies.29,30 It should be validated in other settings, in particular in the general population.

Ours is the first large scale prospective follow up study using serum pepsinogen and anti-H pylori antibody to estimate the incidence of gastric cancer in the general population. Subjects in our study were consecutive participants in a general health checkup programme, a very common activity in Japan.17,22,24,31 Participants were symptom free, and those with peptic ulcers or gastric cancers were excluded from the cohort, as they were receiving treatments such as gastric acid suppression, H pylori eradication, or surgery. It is likely that our subjects represent the healthy Japanese population, with fewer biases than hospitalised patients. Moreover, as was shown by the average number of endoscopic examinations, gastric cancer development was closely and evenly surveyed in each group. Thus gastric cancer development could be accurately detected with minimum delay or aberration. The present study would no doubt estimate precise incidence rates of gastric cancer in the general population.

Serological markers were used in this study for gastric atrophy status induced by H pylori. Subjects were stratified according to H pylori antibody and pepsinogen status into groups A, B, C, and D. Group A (negative for H pylori and normal pepsinogen normal) was assumed to have no H pylori infection whereas the other groups were infected with H pylori. As was discussed in our previous study, group D was assumed to have the most advanced gastric atrophy due to H pylori infection in spite of being negative for H pylori antibody.17 Pepsinogen levels indicated the most severe gastric atrophy in group D.4,20,32 It is generally known that the H pylori burden decreases dramatically in such situations,33 and H pylori antibody spontaneously disappears.34 In fact, our preliminary data from the same cohort of the present study showed a small but significant progression of gastric atrophy and reduction of serum pepsinogen at eight year intervals in groups B and C, leading to group advancement in some patients.35

In the present study, among 6983 subjects analysed, 43 developed gastric cancer during the follow up period. The annual incidence rates of groups A–D steadily increased in this order. Our results are in agreement with those of Uemura et al, irrespective of the difference in study population and diagnostic method for H pylori.5 In addition, we are able to define a super high risk group for the development of gastric cancer (group D). Group D comprised 25.7% of subjects older than 60 years, and gastric cancer developed at the highest rates of 1.8%/year in males and 1.5%/year in females from this group. In contrast, group B (H pylori positive and pepsinogen normal) showed the same low risk as group A without H pylori infection. Approximately 58% of those with H pylori infection could be regarded as having a negligible risk for at least five years.

In terms of histopathological features, cardiac cancers, which have been suspected to have little association with H pylori,2,16 all developed in group A. Both intestinal- and diffuse-type gastric cancers were highly associated with H pylori infection, as has been reported in previous studies.12,16

In the present study, all of the gastric cancers detected by endoscopic follow up were resectable and most are expected to be curative. Although it is still to be confirmed by longer observation, close endoscopic follow up could be valuable for subjects in the high risk group. Furthermore, eradication of H pylori may be recommended in the population, even in low risks group who are infected with H pylori, if steady progression of gastric atrophy is assumed.

In conclusion, we prospectively observed the natural course of gastric cancer development in the Japanese general population. We found H pylori antibody and serum pepsinogen to be good predictive markers for the development of gastric cancer. There is an increasing tendency for gastrocarcinogenesis with progression of H pylori infection. We believe this study provides definitive baseline data for future prevention studies in gastric cancer.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Part of this study was presented in the research forum at the Annual meeting of the American Gastroenterology Association, Orlando, Florida, 20 May 2003.

REFERENCES

- 1.Forman D, Newell DG, Fullerton F, et al. Association between infection with Helicobacter pylori and risk of gastric cancer: evidence from a prospective investigation. BMJ 1991;302:1302–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1991;325:1127–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med 1991;325:1132–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The EUROGAST Study Group. An international association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. The EUROGAST Study Group. Lancet 1993;341:1359–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med 2001;345:784–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maeda S, Yoshida H, Ogura K, et al. H. pylori activates NF-kappaB through a signaling pathway involving IkappaB kinases, NF-kappaB-inducing kinase, TRAF2, and TRAF6 in gastric cancer cells. Gastroenterology 2000;119:97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogura K, Maeda S, Nakao M, et al. Virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori responsible for gastric diseases in Mongolian gerbil. J Exp Med 2000;192:1601–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maeda S, Akanuma M, Mitsuno Y, et al. Distinct mechanism of Helicobacter pylori-mediated NF-kappa B activation between gastric cancer cells and monocytic cells. J Biol Chem 2001;276:44856–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirata Y, Maeda S, Mitsuno Y, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein activates serum response element-driven transcription independently of tyrosine phosphorylation. Gastroenterology 2002;123:1962–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asaka M, Kimura T, Kato M, et al. Possible role of Helicobacter pylori infection in early gastric cancer development. Cancer 1994;73:2691–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansson LE, Engstrand L, Nyren O, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection: independent risk indicator of gastric adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 1993;105:1098–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kikuchi S, Wada O, Nakajima T, et al. Serum anti-Helicobacter pylori antibody and gastric carcinoma among young adults. Research Group on Prevention of Gastric Carcinoma among Young Adults. Cancer 1995;75:2789–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin JT, Wang LY, Wang JT, et al. A nested case-control study on the association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer risk in a cohort of 9775 men in Taiwan. Anticancer Res 1995;15:603–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webb PM, Yu MC, Forman D, et al. An apparent lack of association between Helicobacter pylori infection and risk of gastric cancer in China. Int J Cancer 1996;67:603–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaser MJ, Kobayashi K, Cover TL, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in Japanese patients with adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Int J Cancer 1993;55:799–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, et al. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology 1998;114:1169–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamaji Y, Mitsushima T, Ikuma H, et al. Inverse background of Helicobacter pylori antibody and pepsinogen in reflux oesophagitis compared with gastric cancer: analysis of 5732 Japanese subjects. Gut 2001;49:335–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samloff IM. Cellular localization of group I pepsinogens in human gastric mucosa by immunofluorescence. Gastroenterology 1971;61:185–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samloff IM, Liebman WM. Cellular localization of the group II pepsinogens in human stomach and duodenum by immunofluorescence. Gastroenterology 1973;65:36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samloff IM, Varis K, Ihamaki T, et al. Relationships among serum pepsinogen I, serum pepsinogen II, and gastric mucosal histology. A study in relatives of patients with pernicious anemia. Gastroenterology 1982;83:204–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borch K, Axelsson CK, Halgreen H, et al. The ratio of pepsinogen A to pepsinogen C: a sensitive test for atrophic gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol 1989;24:870–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miki K, Ichinose M, Kakei N, et al. The clinical application of the serum pepsinogen I and II levels as a mass screening method for gastric cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 1995;362:139–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamamoto I, Fukuda Y, Mizuta T, et al. Evaluation of nine commercial serodiagnostic kits for the detection of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan (in Japanese with English abstract). Res Forum Dig Dis 1994;1:75–85. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe Y, Kurata JH, Mizuno S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. A nested case-control study in a rural area of Japan. Dig Dis Sci 1997;42:1383–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lauren P . The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. Acta Pathol Microbiol Sand 1965;64:31–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide incidence of eighteen major cancers in 1985. Int J Cancer 1993;54:594–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stadtlander C, Waterbor JW. Molecular epidemiology, pathogenesis and prevention of gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis 1999;20:2195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, 7–14 June 1994. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 1994;61:1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kokkola A, Haapiainen R, Laxen F, et al. Risk of gastric carcinoma in patients with mucosal dysplasia associated with atrophic gastritis: a follow up study. J Clin Pathol 1996;49:979–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whiting JL, Sigurdsson A, Rowlands DC, et al. The long term results of endoscopic surveillance of premalignant gastric lesions. Gut 2002;50:378–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitahara F, Kobayashi K, Sato T, et al. Accuracy of screening for gastric cancer using serum pepsinogen concentrations. Gut 1999;44:693–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miki K, Ichinose M, Shimizu A, et al. Serum pepsinogens as a screening test of extensive chronic gastritis. Gastroenterol Jpn 1987;22:133–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karnes WE Jr, Samloff IM, Siurala M, et al. Positive serum antibody and negative tissue staining for Helicobacter pylori in subjects with atrophic body gastritis. Gastroenterology 1991;101:167–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kokkola A, Kosunen T, Puolakkainen P, et al. Spontaneous disappearance of Helicobacter pylori antibodies in patients with advanced atrophic corpus gastritis. APMIS 2003;111:619–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watabe H, Yamaji Y, Okamoto M, et al. Progression of gastric atrophy correlates with serum pepsinogen status. Gastroenterology 2004;126 (suppl 2) :A66. [Google Scholar]