Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is one of two well described forms of hereditary colorectal cancer. The primary cause of death from this syndrome is colorectal cancer which inevitably develops usually by the fifth decade of life. Screening by genetic testing and endoscopy in concert with prophylactic surgery has significantly improved the overall survival of FAP patients. However, less well appreciated by medical providers is the second leading cause of death in FAP, duodenal adenocarcinoma. This review will discuss the clinicopathological features, management, and prevention of duodenal neoplasia in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis.

FAMILIAL ADENOMATOUS POLYPOSIS

FAP is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by a germline mutation in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene. FAP is characterised by the development of multiple (⩾100) adenomas in the colorectum. Colorectal polyposis develops by age 15 years in 50% and age 35 years in 95% of patients. The lifetime risk of colorectal carcinoma is virtually 100% if patients are not treated by colectomy.1

Patients with FAP can also develop a wide variety of extraintestinal findings. These include cutaneous lesions (lipomas, fibromas, and sebaceous and epidermoid cysts), desmoid tumours, osteomas, occult radio-opaque jaw lesions, dental abnormalities, congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium, and nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. In addition, FAP patients are at increased risk for several malignancies, such as hepatoblastoma, pancreatic, thyroid, biliary-tree, and brain tumours.1

Other gastrointestinal manifestations commonly found in FAP patients are duodenal adenomas, and gastric fundic gland and adenomatous polyps. Of concern, duodenal cancer is the second leading cause of death after colorectal cancer in these individuals.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF DUODENAL POLYPS AND CANCER

After the colorectum, the duodenum is the second most commonly affected site of polyp development in FAP (fig 1 ▶).2,3 Duodenal adenomas can be found in 30–70% of FAP patients2–4 and the lifetime risk of these lesions approaches 100%.4,5

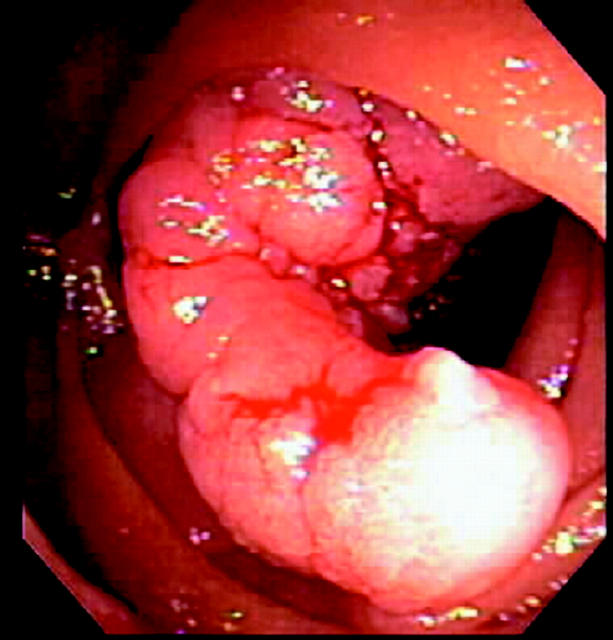

Figure 1.

Polyps in the second part of the duodenum in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis.

Duodenal/periampullary adenocarcinoma is the leading cause of death in FAP after colorectal cancer.6 These patients have a 100–330-fold higher risk of duodenal cancer compared with the general population.7,8 Of note, duodenal cancer is rare in the population, with an incidence of 0.01–0.04%.9 Estimates of the cumulative risk of developing duodenal cancer in FAP range from 4% at age 70 years to 10% at age 60 years.10,11 Recently, a large prospective five nation study set the cumulative incidence rate of duodenal cancer at 4.5% by age 57 years. The median age of duodenal cancer development was 52 years (range 26–58).4

UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL POLYP DISTRIBUTION AND TYPE

Polyps can be found throughout the duodenum, but the second and third portion and the periampullary region are the most commonly affected sites. This pattern probably reflects exposure of duodenal mucosa to bile acids,12 suggesting a role for these compounds in duodenal carcinogenesis.13 Most polyps in the duodenum are adenomas whereas polyps in the stomach are usually benign non-adenomatous fundic gland lesions. However, approximately 10% of gastric polyps are adenomas.3,12 Interestingly, Japanese and Korean FAP patients have a 3–4 times higher risk of gastric cancer compared with the general population14,15 whereas no increased risk has been found in Western countries.8 Besides polypoid neoplasia, flat adenomas can be found in the duodenum of approximately 30% of FAP patients and careful follow up of these lesions is recommended.16

GENOTYPE-PHENOTYPE CORRELATION IN DUODENAL POLYPOSIS

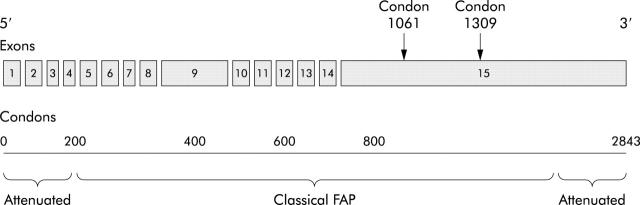

The cause of FAP is germline mutation of the APC gene. The APC gene is a tumour suppressor gene with 15 exons that encodes a 2843 amino acid protein with a molecular weight of 309 kDa. One third of all germline mutations occur in codons 1061 and 1309 (fig 2 ▶).1

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, consisting of 15 exons and 2843 codons. One third of all germline mutations occur in codons 1061 and 1309. Mutations at the extremes of the APC gene present as attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis.

Several genotype-phenotype correlations for colonic polyposis in FAP have been established. Mutations between codon 1250 and codon 1464 are associated with profuse polyposis (>5000 colorectal polyps) and those in codon 1309 with early onset of adenoma development (10 years earlier) and colorectal cancer (age <35 years).17,18 Mutations at the 5′ and 3′ extremes of the APC gene cause attenuated FAP, characterised by oligopolyposis (less than 100 colorectal polyps) at presentation and later onset of colorectal cancer development (age >50 years).1

The relationship between severity of duodenal polyposis and mutations in the APC gene is less well understood. Taken together, published reports are inconsistent (table 1 ▶). One study failed to detect a correlation between the site of mutation and the severity of duodenal polyposis.17 In another, severe duodenal polyposis was found in patients with 5′ mutations.19 Still others correlate severe duodenal disease with mutations in the central part of the gene.20 However, most reports indicate that mutations in exon 15 of the APC gene, particularly distal to codon 1400, give rise to a severe duodenal phenotype.11,18,21–27

Table 1.

Genotype-phenotype correlations for upper gastrointestinal polyposis in familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

| Author | No of FAP patients | Findings | Conclusion |

| Groves21 | 129 patients with known APC mutation | 245 patients underwent upper GI endoscopy, 129 had known germline mutations. Mutations after codon 1400 tend to give rise to more severe duodenal polyposis | Exon 15 (distal) |

| Attard22 | 15 patients with known APC mutation | 24 paediatric patients from 21 families underwent upper GI endoscopy. 15 patients had known APC mutation. Patients with upper GI adenomas were more likely to have mutations between codons 1225 and 1694 | Exon 15 (distal) |

| Matsumoto23 | 4 members of 1 family | 4 patients from 1 family with severe duodenal adenomatosis and a frame shift mutation in codon 1556 | Exon 15 (distal) |

| Legget24 | 2 members of 1 family | 2 members of 1 family with sparse colonic but severe upper GI adenomatosis and a 2 bp deletion in codon 1520 | Exon 15 (distal) |

| Trimbath25 | 1 (AFAP) | AFAP patient presenting with ampullary adenocarcinoma and distal 3′ (exon 15) APC mutation | Exon 15 |

| Bjork11 | 15 patients with known APC mutation | 19 patients with stage IV duodenal adenomatosis or carcinoma.15 APC mutations were detected, 12 were downstream of codon 1051 in exon 15 | Exon 15 |

| Bertario18 | 399 patients from 78 families with known APC mutation | Mutations between codons 976 and 1067 were associated with 3–4-fold increased risk of duodenal adenomas | Exon 15 (proximal) |

| Enomoto26 | 62 patients from 30 families with known APC mutation | Patients with germline mutations between codons564 and 1465 have higher frequencies of upper GI adenomas than patients with a mutation between codons 157 and 416 | Exon 10–15 |

| Matsumoto27 | 34 patients from 25 families with known APC mutation | Patients with distal (exon 10–15) APC mutations have higher prevalence of duodenal adenomas than patients with proximal (exon 1–9) mutations | Exon 10–15 |

| Saurin20 | 33 patients from 17 families with known APC mutation | Mutation in central part (279–1309), risk factor for development of severe duodenal adenomatosis | Codon 279–1309 |

| Soravia19 | 7 AFAP kindreds | Kindreds with 5′ end mutations (exon 4 and 5) have more duodenal adenomas than kindreds with mutations in exon 9 and 3′ distal end | Exon 4 and 5 |

| Friedl17 | 86 patients from 77 families with known APC mutation | 134 patients from 125 families had duodenal adenomas. From 86 patients the germline mutation was known No correlation between site of mutation and duodenal adenomatosis | No correlation |

APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; COX, cyclooxygenase; AFAP, attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis.

UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL ADENOMA-CARCINOMA SEQUENCE

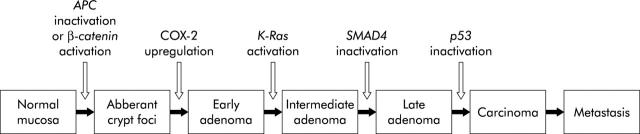

The adenoma-carcinoma sequence describes colorectal carcinogenesis as a stepwise progression of normal intestinal mucosa to aberrant crypt foci, adenoma, and finally invasive carcinoma (fig 3 ▶). Activation of the Wnt signalling pathway, by biallelic inactivating APC mutation or an activating β-catenin mutation, can be regarded as the initiating step. Subsequent mutations in tumour suppressor genes (for example, p53 and SMAD4) and oncogenes (for example, K-Ras) lead to neoplastic progression of the adenoma-carcinoma sequence.28 Also, expression of important cell regulatory proteins is changed. One of these is cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), which is increasingly expressed in consecutive stages of the adenoma-carcinoma sequence.29,30

Figure 3.

The adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Activation of the Wnt signalling pathway, by an inactivating adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) mutation or an activating β-catenin mutation, is regarded as the first step in the adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Then, additional mutations in oncogenes (for example, K-Ras) and tumour suppressor genes (for example, p53 and SMAD4) drive further progression of the adenoma-carcinoma sequence. COX-2, cyclooxygenase 2.

The adenoma-carcinoma sequence, first identified for colorectal tumorigenesis, has been observed in the setting of duodenal carcinogenesis in patients with both FAP and sporadic disease. Spigelman and colleagues31 found a strong association between duodenal adenomas and duodenal cancer, showing that villous histology, moderate or severe dysplasia, and the presence of stage IV duodenal polyps were associated with malignant change. Also, case reports of duodenal carcinoma development in or near adenomas have been described.32,33 Moreover, Kashiwagi et al noted p53 overexpression in 25% of tubular, 72% of tubulovillous/villous adenomas, and 100% of duodenal carcinomas,34 and K-Ras codon 12 mutations have been detected in duodenal adenomas and carcinomas.35 In addition, SMAD4 mutations play a role in polyp development in the upper intestine in mice.36 Lastly, Resnick and colleagues37 demonstrated that transforming growth factor α (TGF-α) expression was greater in duodenal carcinomas than in adenomas, and that epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-R) expression correlated with the degree of dysplasia in duodenal adenomas. These studies reveal that additional molecular alterations drive the transition of adenoma into carcinoma.

COX-2 is known to be an important mediator of colorectal neoplasia progression but expression of COX-2 has not been extensively studied in duodenal or upper gastrointestinal adenomas. Shirvani and colleagues38 found constitutive COX-2 expression in normal duodenum and oesophagus and significantly higher levels in oesophageal dysplastic tissues. Furthermore, these investigators showed that COX-2 expression in Barrett’s oesophagus increased in response to pulses of acid or bile salts. COX-2 expression is also elevated in gastric cancers.39

CLASSIFICATION OF DUODENAL POLYPOSIS

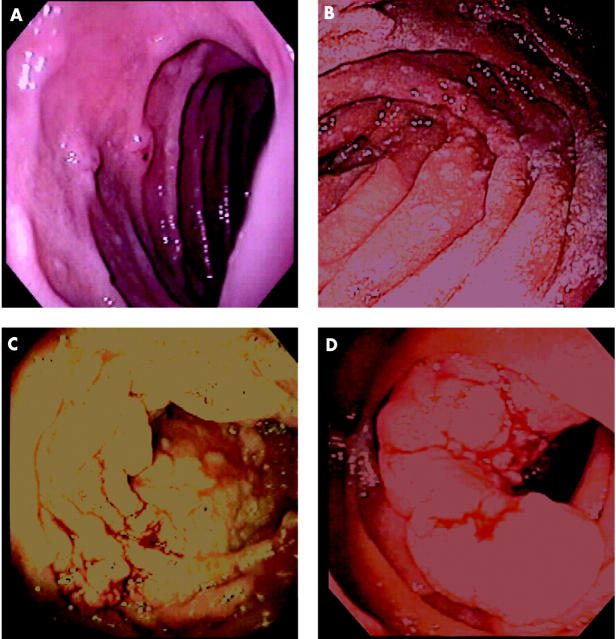

The most useful system for rating the severity of duodenal polyposis was developed by Spigelman and colleagues. This classification describes five (0–IV) stages. Points are accumulated for number, size, histology, and severity of dysplasia of polyps (table 2 ▶). Stage I indicates mild disease whereas stages III–IV imply severe duodenal polyposis (fig 4 ▶).12 Approximately 70–80% of FAP patients have stage II or stage III duodenal disease, and 20–30% have stage I or stage IV disease.12,40 The estimated cumulative incidence of stage IV duodenal disease however is 50% at age 70 years.4,41

Table 2.

Spigelman classification for duodenal polyposis in familial adenomatous polyposis

| Criterion | Points | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Polyp number | 1–4 | 5–20 | >20 |

| Polyp size (mm) | 1–4 | 5–10 | >10 |

| Histology | Tubular | Tubulovillous | Villous |

| Dysplasia | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

Stage 0, 0 points; stage I, 1–4 points; stage II, 5–6 points; stage III, 7–8 points; stage IV, 9–12 points.

Figure 4.

Spigelman stages of duodenal polyposis. (A) Stage I. (B) Stage II. (C) Stage III. (D) Stage IV.

Several investigators have shown that duodenal polyposis slowly progresses. One study followed 114 FAP patients for 51 months and found progression of polyps in size (26%), number (32%), and histology (11%).42 When individuals are followed for longer, duodenal polyps advance in Spigelman stage. Heiskanen and colleagues5 reported worsening polyposis in 73% of 71 FAP patients followed for 11 years. The median interval for progression by one stage was 4–11 years. Another group reported a stage change in 42% of patients with an average time of evolution by one stage of 3.9 years. Also, the risk of developing stage III or IV disease exponentially increases after age 40 years.43

The Spigelman classification also correlates with risk of duodenal malignancy. Stages II, III, and IV disease are associated with a 2.3%, 2.4%, and 36% risk of duodenal cancer, respectively.40

MANAGEMENT

Surveillance

As noted, duodenal polyposis is ingravescent over time. Consequently, surveillance of the upper gastrointestinal tract for the development of neoplasia by end and side viewing scopes is recommended by most authorities. One long term upper tract surveillance study of 114 FAP patients failed to prevent the development of duodenal adenocarcinoma in six patients.40 These findings emphasise the need to adjust the frequency of surveillance and to entertain surgical treatment with increasing severity of disease. Recommendations concerning the age of initiation of upper tract surveillance are not uniform. Some propose that screening for upper gastrointestinal disease should start at the time of FAP diagnosis.44 The NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network), after review of all case reports of duodenal cancer in FAP patients, recommended a baseline upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examination at 25–30 years of age.45 Guidelines for continued endoscopic surveillance after baseline examination have been developed according to Spigelman stage by several authorities.40,45 In general, recommendations include stage 0 every 4 years; stage I every 2–3 years; stage II every 2–3 years; stage III every 6–12 months with consideration for surgery; and stage IV strongly consider surgery (table 3 ▶).

Table 3.

Recommendations for management of duodenal polyposis in familial adenomatous polyposis, adjusted to the Spigelman stage of duodenal polyposis

| Spigelman stage | Endoscopic frequency | Chemoprevention | Surgery |

| Stage 0 | 4 years | No | No |

| Stage I | 2–3 years | No | No |

| Stage II | 2–3 years | +/− | No |

| Stage III | 6–12 months | +/− | +/− |

| Stage IV | 6–12 months | +/− | Yes |

Endoscopic treatment

Endoscopic treatment options for duodenal lesions include snare excision, thermal ablation, argon plasma coagulation, and photodynamic therapy (PDT). Most reports of endoscopic therapy use snare excision. However, duodenal adenomas are often flat non-polypoid structures and, therefore, difficult to remove using conventional snare excision. For these cases, prior submucosal saline/adrenaline infusion may facilitate removal and reduce the risk of haemorrhage and perforation.40 In addition, thermal ablation,5,46 argon plasma coagulation,47 or PDT48–51 may be suitable.

PDT is a non-thermal technique relying on the combined effect of a low power activating light and a photosensitising drug that is selectively retained within neoplastic tissue with minimal retention in surrounding normal tissue. Few reports of PDT for adenomas in the gastrointestinal tract exist. Loh and colleagues50 successfully applied PDT for resection of colorectal adenomas: 7/9 treated adenomas were eradicated. Others have used PDT for resection of neoplastic lesions in the upper gastrointestinal tract but results are disappointing (table 4 ▶).48,49,51

Table 4.

Endoscopic treatment for duodenal neoplastic lesions

| Author | Treatment | Follow up | Patients | Outcome | Postoperative |

| Soravia52 | Endoscopic resection nos | 4–34 months &;(mean 18) | 6 FAP | Recurrence of duodenal adenomas in all 5 surviving patients | 1 patient died of acute pancreatitis after endoscopic ampullectomy |

| Bertoni53 | Snare papillectomy | 18 months | 2 FAP | Recurrence in 1 patient, successfully retreated | 1 oozing-type haemorrhage and 1 mild pancreatitis, controlled by conservative measures |

| Morpurgo44 | Snare polypectomy (3) argon plasma therapy (2) | 6–24 months &;(mean 19) | 5 FAP | Recurrence in 3 patients | No postoperative complications |

| Alarcon46 | Snare polypectomy and thermal contact ablation | 14–83 months &;(mean 43.5) | 3 FAP | Recurrence in 3 patients | NS |

| Heiskanen5 | Snare excision (5), YAG laser coagulation (1) | 0.4–15.1 years &;(median 6.8) | 6 FAP | No significant difference in Spigelman stage preoperative and at latest endoscopy | Patient treated with YAG laser developed mild pancreatitis |

| Norton54 | Ampullary ablative therapy | 1–134 months &;(median 24) | 59 FAP, 32 sporadic | Return to normal histology in 44% of sporadic and 34% of FAP lesions | 12 patients had mild complications, 3 severe complications: 1 duodenal stenosis, 1 postcoagulation syndrome, 1 necrotising pancreatitis |

| Norton55 | Snare excision of papilla | 2–32 months &;(median 9) | 15 FAP, 11 sporadic | Recurrence rate of adenomatous tissue of 10% | 2 minor bleedings, 4 mild pancreatitis, 1 duodenal perforation |

| Mlkvy49 | PDT with ALA or Photofrin | 4 FAP patients with duodenal polyps | Superficial necrosis and no polyp reduction after PTD with ALA. Deep necrosis and moderate polyp reduction after PDT using Photofrin. | Mild skin photosensitivity using Photofrin | |

| Regula48 | PDT with ALA | 2 duodenal adenomas, 3 ampullary carcinomas | Superficial necrosis of adenomas and in 2 adenocarcinomas. 1 adenocarcinoma unaffected. | Side effects included mild skin photosensitivity, nausea/vomiting, and transient increases in ASAT | |

| Loh50 | PDT with HpD or Photofrin | 3–50 months &;(median 5.5) | 8 patients with 9 colorectal adenomas | 7 adenomas successfully eradicated | No local complications |

| Abulafi51 | PDT with HpD | 10 patients with ampullary carcinoma unsuitable for surgery | Remission for 8–12 months in 3 patients with small tumours. In 4 patients with small tumours bulk was reduced. No improvement in patients with extensive disease | 3 patients with moderate skin sensitisation |

NS, not stated; PDT, photodynamic therapy; ALA, 5-aminolaevulinic acid; HpD, haematoporphyrin derivate or Photofrin; FAP, familial adenomatous polyposis.

Endoscopic treatment of duodenal neoplasia for Spigelman stage II and III polyposis has been pursued by some investigators. However, the benefit of this approach in eradicating duodenal polyposis is difficult to justify but may be useful in individual cases. Literature reports of endoscopic treatment for FAP patients with duodenal/ampullary polyps are summarised in table 4 ▶. These publications reveal that endoscopic treatment is usually insufficient to guarantee a polyp-free duodenum and fraught with complications. Recurrence rates of adenomatous tissue in duodenum of FAP patients treated endoscopically range from 50% to 100%.44,46,52,53 Lower recurrence was reported by Norton and colleagues54,55 but their study population also included patients with sporadic duodenal lesions. In summary, endoscopic treatment appears useful in individual cases but follow up remains necessary and surgical intervention is often indicated in patients with more severe polyposis.

Surgery

Surgical options utilised to treat duodenal polyposis include local surgical treatment (duodenotomy with polypectomy and/or ampullectomy), pancreas and pylorus sparing duodenectomy, and pancreaticoduodenectomy. There are no randomised studies published to help guide surgical selection.

Publications of local surgical treatment with duodenotomy for duodenal polyposis in FAP patients are summarised in table 5 ▶. This surgery has proven insufficient to guarantee a polyp-free duodenum, with most studies reporting high recurrence rates in FAP patients with severe duodenal adenomatosis.5,52,44,46,56–59 Farnell and colleagues60 found a lower recurrence of duodenal polyps of 32% and 43% at five and 10 years of follow up, respectively. But this investigation also included sporadic duodenal polyposis cases and concludes that recurrence was higher in patients with a polyposis syndrome. Nevertheless, duodenotomy may be indicated in patients with one or two dominant worrisome duodenal lesions in otherwise uninvolved or minimally involved intestine. In the future, the postoperative use of chemopreventive medication may be a useful strategy.

Table 5.

Local surgical treatment (duodenotomy with polypectomy and/or ampullectomy) for duodenal neoplastic lesions

| Author | Treatment | Follow up | Patients | Outcome | Postoperative |

| Soravia52 | Duodenotomy with polypectomy (1) or ampullectomy (4) | 4–34 months &;(mean 18) | 5 FAP | Recurrence in 4 patients. 1 patient died of cancer | 1 transient duodenal fistula |

| Morpurgo44 | Transduodenal ampullectomy (1) or polyp excision (1) | 6–24 months &;(mean 19) | 2 FAP | Recurrence in 1 patient | 1 severe pancreatitis |

| Alarcon46 | Local resection | 8–33 months &;(mean 20.2) | 5 FAP | Recurrence in 4 patients. 1 had progressive metastatic adenocarcinoma | NS |

| Heiskanen5 | Duodenotomy | 0.4–15.1 years &;(median 6.8) | 15 FAP | No significant difference in Spigelman stage preoperative and at latest endoscopy | No postoperative complications |

| Penna56 | Duodenotomy with polypectomy | 5–36 months &;(mean 13.3) | 12 FAP | Recurrence in 12 patients | NS |

| Penna57 | Duodenotomy with polypectomy | 36–72 months &;(mean 53) | 6 FAP | Recurrence in 6 patients | 1 cholecystectomy for cholecystitis, 2 duodenal fistulas |

| de Vos tot Nederveen58 | Duodenotomy with ampullectomy | 4–13 months &;(mean 11) | 8 FAP | Recurrence in 6 patients | 1 minor morbidity* |

| de Vos tot Nederveen58 | Duodenotomy with polypectomy | 5–103 months &;(mean 29) | 22 FAP | Recurrence in 17 patients. 1 death from metastatic disease | 1 minor morbidity* |

| Ruo59 | Duodenotomy with ampullectomy | 35 months | 1 FAP | Gastric cancer arising from a polyp at 35 months | No postoperative complications |

| Farnell60 | Transduodenal local excision | 10 years | 53 sporadic and FAP patients | Recurrence rate of 32% at 5 years and 43% at 10 years of follow up | 3 pancreatitis, 3 leaks, 2 delayed gastric emptying, 2 ileus, 1 fluid overload |

*That is, wound infection, atelectasis, or urinary tract infection.

NS, not stated; FAP, familial adenomatous polyposis.

More radical surgery, in the form of classical pancreaticoduodenectomy, or pylorus or pancreas preserving duodenectomy, has been indicated for patients with severe polyposis (stage IV), failed endoscopic or local surgical treatment, and carcinoma development. Others recommend consideration of surgery in patients with stage III polyposis.44,46,52,57–63 Low recurrence rates of polyposis have been reported with these procedures (table 6 ▶). The specific choice of procedure appears related to local expertise and the site of polyp involvement. Use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatograpy to evaluate biliary duct involvement in patients with ampullary lesions or those with laboratory test perturbations has been suggested to direct appropriate surgery. In the final analysis, the morbidity and mortality of these surgeries must be weighed against the risk of developing duodenal adenocarcinoma.

Table 6.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy and pylorus or pancreas preserving duodenectomy for duodenal neoplastic lesions

| Author | Treatment | Follow up | Patients | Outcome | Postoperative |

| Soravia52 | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | NS | 1 FAP | Unknown | NS |

| Morpurgo44 | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | NS | 4 FAP | No recurrence reported | Increased number of bowel movements. One patient required pouch excision and end ileostomy to control diarrhoea. 3 patients experienced weight loss, 1 patients had episodes of pancreatitis |

| Alarcon46 | Pancreas sparing duodenectomy | 40–50 months &;(mean 45.7) | 3 FAP | No recurrence. Two of three patients had a small tubular adenoma in the duodenal bulb. | NS |

| Penna57 | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 9–108 months &;(mean 42) | 7 FAP severe duodenal polyposis | No recurrence in patients treated for severe duodenal polyposis. | 1 pancreatic fistula, 1 upper GI haemorrhage |

| 1–9 years | 5 FAP duodenal cancer | Only 1 patients with duodenal cancer survived >4 years | Resection not possible in 2 because of peritoneal carcinomatosis or distal lymph node involvement | ||

| de Vos tot &;Nederveen58 | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 7–96 months &;(mean 47) | 23 FAP | Recurrence in 3, 6 died of metastatic disease | 5 minor morbidity*, 12 major morbidity†, 1 patient died of postoperative complications |

| de Vos tot &;Nederveen58 | Pancreas sparing duodenectomy | 2–15 months &;(mean 11) | 6 FAP | No recurrence | 1 minor morbidity*, 3 major morbidity† |

| de Vos tot &;Nederveen58 | Pylorus preserving duodenectomy | 7–93 months &;(mean 45) | 12 FAP | Recurrence in 3 of 9, 3 died of metastatic disease | 1 minor morbidity*, 4 major morbidity† |

| Ruo59 | (Pylorus preserving) pancreaticoduodenectomy | 37–162 months &;(mean 70.5) | 7 FAP | 1 patient developed jejunal adenomas 12 years after operation | 1 patient developed pancreatic ascites |

| Chung61 | Pancreas sparing duodenectomy | 0.5–3 years &;(mean 2.1) | 4 FAP | No recurrence | 1 gastric retention, 1 pancreatic fistula |

| Kalady[62 | Pancreas sparing duodenectomy | 10 years | 3 FAP | 1 had polyp recurrence in jejunum at 5 years of follow up | 1 postoperative wound infection, 1 biliary leak |

| Balladur63 | (Pylorus preserving) pancreaticoduodenectomy | 24 and 28 months | 2 FAP | No recurrence | NS |

| Farnell60 | (Pancreas sparing) pancreaticoduodenectomy | 0.3–16 years &;(mean 5.6) | 25 FAP and sporadic | No recurrences | 10 leaks, 4 delayed gastric empytying, 1 delirium tremens, 3 abcesses. 1 patient died from bleeding and sepsis related to hepaticojejunostomy leak. Morbidity was higher after pancreas sparing duodenotomy. |

*That is, wound infection, atelectasis, or urinary tract infection.

†That is, anastomotic leakage, fistula formation, wound abscess, sepsis, or pancreatitis.

NS, not stated; FAP, familial adenomatous polyposis.

Pharmacological treatment

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) regress colorectal adenomas in FAP patients. The value of these agents for duodenal polyposis regression is unclear. Studies of duodenal adenoma regression have primarily utilised sulindac (NSAID) and selective COX-2 inhibitors (table 7 ▶).

Table 7.

Familial adenomatous polyposis patients treated with sulindac, celecoxib, or refecoxib for duodenal adenomas

| Author | Treatment &;(dose/day) | Type of study | Duration | Patients | Outcome | Side effects |

| Nugent64, &;Debinski65 | Sulindac &;400 mg | Randomised controlled clinical trial | 6 months | 11 | Number of polyps ↓ in 5 patients (p = 0.12 v placebo). Second evaluation: effect on small polyps (⩽2mm) (p = 0.02) | 1 patient with indigestion |

| Seow-Choen66* | Sulindac &;300 mg | Randomised controlled clinical trial | 6 months | 15 | No effect | No adverse events reported |

| Richard67 | Sulindac &;300 mg | Clinical trial | 10–24 months | 5 | No regression of small residual polyps. 3 patients developed large polyps; 1 breakthrough carcinoma | 2 patients with abdominal cramp. 1 patient with upper GI bleeding |

| Phillips68 | Celecoxib &;800 mg | Randomised controlled clinical trial | 6 months | 30 | Number of polyps ↓ compared to placebo (p = 0.03) | 1 patient with allergic reaction. 1 patient with symptoms of dyspepsia |

| Winde69 | Sulindac &;50–300 supp dose &;reduction | Prospective, controlled, non-randomised phase II dose finding study | Up to 4 years | xx | No effect on upper GI polyps | 2 patients with mild gastritis due to NSAID |

| Maclean70† | Refecoxib &;25 mg | Randomised controlled clinical trial | 6 months | 6 | Improvement in 2 patients with stage III polyposis; no effect in 4 patients; no effect in ursodeoxycholic acid group | |

| Parker71 | Sulindac &;300 mg | Case report | 1 | No recurrence of duodenal polyps | ||

| Theodore72 | Sulindac &;300–400 mg | Case reports | 5 and 14 years | 2 | Sulindac normalised adenomatous ampulla and induced elimination of moderate dysplasia | |

| Waddell73 | Sulindac &;300–400 mg | Case reports | 4.5–5 years | 2 | No effect on gastric and small intestinal polyps |

*The control group was treated with calcium and calciferol.

†The control group was treated with ursodeoxycholic acid.

NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Nugent and colleagues64 compared the effect of sulindac (n = 12) and placebo (n = 12) on the number of duodenal polyps. Polyp number decreased in five patients, increased in one, and was unchanged in five after six months of treatment with sulindac 400 mg/day. The difference between sulindac and placebo treated patients was not significant, possibly due to lack of statistical power. However, a second evaluation of endoscopic videotapes from this cohort revealed a statistically significant effect on small (⩽2 mm) duodenal polyps whereas larger (⩾3 mm) duodenal polyps were unaffected.65 Another randomised crossover trial that compared sulindac 300 mg/day with calcium and calciferol revealed no effect on duodenal polyps in 15 patients who completed six months of treatment with sulindac.66

Richard and colleagues67 treated eight FAP patients with residual small periampullary polyps with sulindac 300 mg/day for at least 10 months. Sulindac was discontinued in three patients due to side effects. Follow up endoscopy was performed every six months or at discontinuation of treatment. None of the patients showed regression of polyps; three patients developed large polyps and one an infiltrating carcinoma while on this drug.

A large randomised trial by Phillips and colleagues,68 with statistical power to detect small differences, investigated the effect of the specific COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib on duodenal polyp number and total polyp area. A 14% decrease in polyp number was found after six months of celecoxib 800 mg/day (n = 32) compared with placebo (n = 17) which was not statistically significant. Paired assessment of endoscopic videotapes, however, revealed a significant difference (p = 0.033), although no effect on polyp area was noted.

Winde and colleagues69 preformed a prospective, controlled, non-randomised phase II dose finding study for sulindac. These investigators compared effects of sulindac suppositories (n = 28) with placebo (n = 10) on rectal and upper gastrointestinal adenomas in patients that underwent colectomy. They found complete or partial reversion of rectal polyps but no effects on duodenal and papillary adenomas.

Preliminary data from a trial comparing another specific COX-2 inhibitor, rofecoxib 25 mg/day, with ursodeoxycholic acid (controls) for duodenal polyps showed a response in two of six patients on rofecoxib and in none of the controls (n = 6). Of note, both responsive patients had stage III disease whereas none of the patients with stage IV disease improved.70

A case report described that sulindac 300 mg/day prevented the recurrence of severe duodenal polyposis in a patient with FAP.71 Another described two patients in whom treatment with sulindac 300–400 mg/day normalised an adenomatous ampulla and eliminated moderate dysplasia.72 In contrast, Waddell and colleagues73 observed no effect of sulindac 300–400 mg/day on gastric and small intestinal polyps in two patients with FAP. In addition to chemoprevention with NSAIDs, H2 blockers have been studied. No significant difference was found in duodenal polyp number or adduct formation between the ranitidine and placebo groups.74

In conclusion, the results of NSAID and other compounds on regression or prevention of duodenal adenomas in FAP appear disappointing, although regression of small adenomas may occur.65

MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF CHEMOPREVENTION WITH NSAIDS

Studies of chemoprevention/regression of duodenal polyps in FAP have primarily utilised NSAIDs. The action of these agents has been divided into COX dependent, mediated through inhibition of the COX enzymes, and COX independent, caused by direct actions of NSAIDs on different molecular mechanisms.

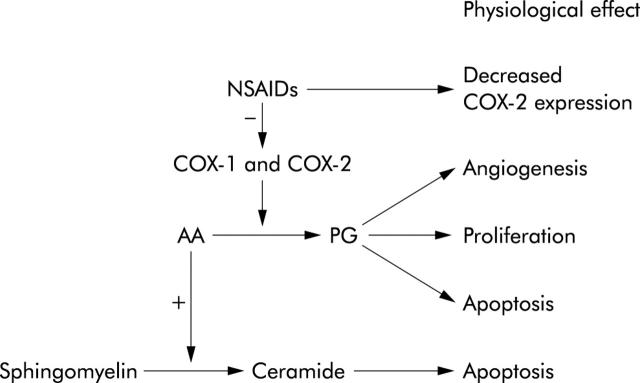

COX dependent mechanisms

NSAIDs are best known for inhibitory effects on COX-1 and COX-2, key enzymes in the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins (PGs) (fig 5 ▶). COX-1 expression occurs in most tissues whereas COX-2 is expressed in response to growth factors, lipopolysaccharide, cytokines, mitogens, and tumour promoters.75 PGs are involved in cellular functions such as angiogenesis and cell proliferation. Therefore, inhibition of PG synthesis could explain part of the antineoplastic effects of NSAIDs. Also, COX-2 inhibition has antiangiogenic effects, as confirmed by several different studies.76–78 COX-2 inhibition may also induce apoptosis, mainly via inhibition of PGE2,79 and inhibit invasive properties of cancer cells. COX-2 was induced by coculture and promoted invasion in vitro that was inhibited by NSAIDs or RNAi against COX-2.80

Figure 5.

Cyclooxygenase (COX) dependent chemopreventive mechanisms of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). PG, prostaglandins; AA, arachidonic acid.

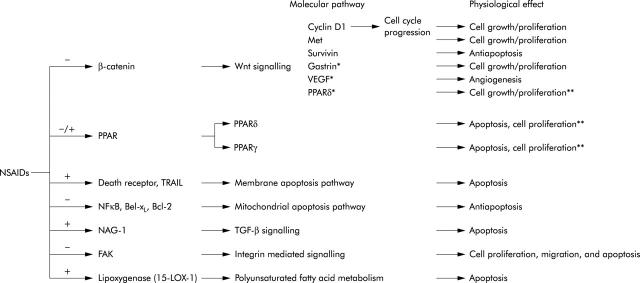

COX independent mechanisms

Several lines of evidence support the importance of COX independent means of action of NSAIDs. Firstly, high doses of NSAIDs induce apoptosis in COX-1 or COX-2 deficient cell lines81 and, secondly, PGs do not rescue these cells from apoptosis.82

Various COX-2 independent targets for NSAIDs have been proposed (fig 6 ▶). β-Catenin appears to be an important target as both indomethacin and exisulind reduce β-catenin expression in colorectal cancer cells.83,84 Also, NSAIDs induce apoptosis via both the membrane bound and mitochondrial pathway. High doses of aspirin antagonise the transcription factor nuclear factor κB,85 which regulates expression of antiapoptotic genes encoding proteins such as TRAF, c-IAP, c-FLIP, Bcl-XL, and A1. Several studies indicate a role for proteins of the Bcl-2 family in the apoptotic response to NSAIDs, and the membrane death receptor apoptotic pathway may also be involved.86 Furthermore, TGF-β signalling is implicated in NSAID chemoprevention.87 NSAIDs affect cell adhesion 88 and lipoxygenase metabolism,89 which reduce colorectal cancer cell invasion and could explain part of the apoptotic response to NSAIDs in colorectal cancer cells. Finally, it appears that members of the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) family, PPARδ and PPARγ, are directly targeted by NSAIDs and PGs.90–93

Figure 6.

Cyclooxygenase (COX) independent chemopreventive mechanisms of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). *Genes with a T cell factor 4 responsive element in their promoter, but no reports of downregulation in response to NSAIDs. **Contradictory reports. PPAR, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; NFκB, nuclear factor κB; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; TRAIL, tumour necrosis factor related apoptosis inducing ligand.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

With improvement in the management of colorectal disease and increased life expectancy, duodenal polyposis and malignancy have emerged as major health problems in patients with FAP. Although most patients eventually develop duodenal polyps, these lesions occur at later age and have lower potential for malignant change compared with colonic polyps. Moreover, duodenal adenomas seem less responsive to chemoprevention with NSAIDs than colonic counterparts.

Currently, the main treatment options for duodenal polyposis are frequent surveillance and targeted endoscopic treatment, adjusted by severity of duodenal lesions. However, these modalities alone cannot guarantee a polyp-free duodenum.40 In patients with severe disease, duodenotomy or duodenectomy may be necessary. Drug therapy of duodenal adenomas would be appropriate treatment but most published reports find no significant effect of NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors on duodenal adenoma regression.

Summary.

▸ FAP is characterised by innumerable adenomatous polyps throughout the colorectum and inevitable development of colorectal carcinoma usually by the fifth decade of life, if colectomy is not performed.

▸ Duodenal adenomas are found in 30–70% of FAP patients.

▸ The lifetime risk of duodenal adenoma development is virtually 100%.

▸ FAP patients have a 100–330-fold higher risk of developing duodenal cancer compared with the general population and an absolute lifetime risk of about 5%.

▸ No clear genotype-phenotype correlation exists, although mutations in the 3′ end of the APC gene (exon 15) appear to cause more severe duodenal manifestations.

▸ First screening for upper gastrointestinal adenoma is recommended at age 25–30 years.

▸ After baseline endoscopy, screening for duodenal polyposis is recommended as per Spigelman stage (see table 3 ▶).

▸ Recurrence of duodenal lesions after local endoscopic or surgical excision is common.

▸ Pancreaticoduodenectomy is the appropriate treatment for Spigelman stage IV duodenal polyposis and can be considered for stage III.

▸ Results of chemoprevention/regression studies for duodenal adenomas are equivocal or disappointing.

Increasing insights into the molecular changes during the adenoma-carcinoma sequence in the duodenum may point to future treatment strategies. Duodenal mucosa is exposed to different environmental factors than that in the colon. Low pH and bile acids may affect control of growth and malignant potential of duodenal tumours.12,13,38 Little is known about the role of potential molecular targets for chemoprevention, including COX-2, PPARδ, PPARγ, TGF-β receptor type II, EGF-R, and inducible nitric oxide synthase. More powerful chemopreventive/regressive regimens could result from combinations of NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors with other drugs, such as selective inhibitors of receptor tyrosine kinases or EGF-R. Further study is needed to understand the molecular changes in duodenal adenoma development and identify molecular targets for chemoprevention and regression of duodenal polyposis.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the Queen Wilhelmina Fund/Dutch Cancer Society, the John G Rangos, Sr Charitable Foundation, the Clayton Fund, and NIH grants 53801, 63721, 51085, and P50 CA 93–16.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trimbath JD, Giardiello FM. Review article: genetic testing and counseling for hereditary colorectal cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:1843–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonelli F, Nardi F, Bechi P, et al. Extracolonic polyps in familial polyposis coli and Gardner’s syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum 1985;28:664–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarre RG, Frost AG, Jagelman DG, et al. Gastric and duodenal polyps in familial adenomatous polyposis: a prospective study of the nature and prevalence of upper gastrointestinal polyps. Gut 1987;28:306–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bulow S, Bjork J, Christensen IJ, et al. Duodenal adenomatosis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut 2004;53:381–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heiskanen I, Kellokumpu I, Jarvinen H. Management of duodenal adenomas in 98 patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Endoscopy 1999;31:412–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galle TS, Juel K, Bulow S. Causes of death in familial adenomatous polyposis. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999;34:808–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pauli RM, Pauli ME, Hall JG. Gardner syndrome and periampullary malignancy. Am J Med Genet 1980;6:205–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Offerhaus GJ, Giardiello FM, Krush AJ, et al. The risk of upper gastrointestinal cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastroenterology 1992;102:1980–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lillemoe K, Imbembo AL. Malignant neoplasms of the duodenum. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1980;150:822–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasen HF, Bulow S, Myrhoj T, et al. Decision analysis in the management of duodenal adenomatosis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut 1997;40:716–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjork J, Akerbrant H, Iselius L, et al. Periampullary adenomas and adenocarcinomas in familial adenomatous polyposis: cumulative risks and APC gene mutations. Gastroenterology 2001;121:1127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spigelman AD, Williams CB, Talbot IC, et al. Upper gastrointestinal cancer in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Lancet 1989;2:783–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahmoud NN, Dannenberg AJ, Bilinski RT, et al. Administration of an unconjugated bile acid increases duodenal tumors in a murine model of familial adenomatous polyposis. Carcinogenesis 1999;20:299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park JG, Park KJ, Ahn YO, et al. Risk of gastric cancer among Korean familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Report of three cases. Dis Colon Rectum 1992;35:996–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwama T, Mishima Y, Utsunomiya J. The impact of familial adenomatous polyposis on the tumorigenesis and mortality at the several organs. Its rational treatment. Ann Surg 1993;217:101–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iida M, Aoyagi K, Fujimura Y, et al. Nonpolypoid adenomas of the duodenum in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (Gardner’s syndrome). Gastrointest Endosc 1996;44:305–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedl W, Caspari R, Sengteller M, et al. Can APC mutation analysis contribute to therapeutic decisions in familial adenomatous polyposis? Experience from 680 FAP families. Gut 2001;48:515–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertario L, Russo A, Sala P, et al. Hereditary colorectal tumor registry. Multiple approach to the exploration of genotype-phenotype correlations in familial adenomatous polyposis. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1698–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soravia C, Berk T, Madlensky L, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in attenuated adenomatous polyposis coli. Am J Hum Genet 1998;62:1290–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saurin JC, Ligneau B, Ponchon T, et al. The influence of mutation site and age on the severity of duodenal polyposis in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;55:342–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groves C, Lamlum H, Crabtree M, et al. Mutation cluster region, association between germ-line and somatic mutations and genotype-phenotype correlation in upper gastrointestinal familial adenomatous polyposis. Am J Pathol 2002;160:2055–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Attard TM, Cuffari C, Tajouri T, et al. Multicenter experience with upper gastrointestinal polyps in pediatric patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:681–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsumoto T, Iida M, Kobori Y, et al. Progressive duodenal adenomatosis in a familial adenomatous polyposis pedigree with APC mutation at codon 1556. Dis Colon Rectum 2002;45:229–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leggett BA, Young JP, Biden K, et al. Severe upper gastrointestinal polyposis associated with sparse colonic polyposis in a familial adenomatous polyposis family with an APC mutation at codon 1520. Gut 1997;41:518–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trimbath JD, Griffin C, Romans K, et al. Attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis presenting as ampullary adenocarcinoma. Gut 2003;52:903–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Enomoto M, Konishi M, Iwama T, et al. The relationship between frequencies of extracolonic manifestations and the position of APC germ-line mutation in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2000;30:82–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto T, Lida M, Kobori Y, et al. Genetic predisposition to clinical manifestations in familial adenomatous polyposis with special reference to duodenal lesions. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:180–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fodde R, Smits R, Clevers H. APC, signal transduction and genetic instability in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2001;1:55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eberhart CE, Coffey RJ, Radhika A, et al. Up-regulation of cyclooxygenase 2 gene expression in human colorectal adenomas and adenocarcinomas. Gastroenterology 1994;107:1183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan KN, Masferrer JL, Woerner BM, et al. Enhanced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in sporadic and familial adenomatous polyposis of the human colon. Scand J Gastroenterol 2001;36:865–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spigelman AD, Talbot IC, Penna C, et al. Evidence for adenoma-carcinoma sequence in the duodenum of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. The Leeds Castle Polyposis Group (Upper Gastrointestinal Committee). J Clin Pathol 1994;47:709–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakatsubo N, Kashiwagi H, Okumura M, et al. Malignant change in a duodenal adenoma in familial adenomatous polyposis: report of a case. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:1566–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kashiwagi H, Kanazawa K, Koizumi M, et al. Development of duodenal cancer in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis. J Gastroenterol 2000;35:856–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kashiwagi H, Spigelman AD, Talbot IC, et al. Overexpression of p53 in duodenal tumours in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg 1996;83:225–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kashiwagi H, Spigelman AD, Talbot IC, et al. p53 and K-ras status in duodenal adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg 1997;84:826–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takaku K, Oshima M, Miyoshi H, et al. Intestinal tumorigenesis in compound mutant mice of both Dpc4 (Smad4) and Apc genes. Cell 1998;92:645–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Resnick MB, Gallinger S, Wang HH, et al. Growth factor expression and proliferation kinetics in periampullary neoplasms in familial adenomatous polyposis. Cancer 1995;76:187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shirvani VN, Ouatu-Lascar R, Kaur BS, et al. Cyclooxygenase 2 expression in Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma: Ex vivo induction by bile salts and acid exposure. Gastroenterology 2000;118:487–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saukkonen K, Rintahaka J, Sivula A, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 and gastric carcinogenesis. APMIS 2003;111:915–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Groves CJ, Saunders BP, Spigelman AD, et al. Duodenal cancer in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): results of a 10 year prospective study. Gut 2002;50:636–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saurin JC, Gutknecht C, Napoleon B, et al. Surveillance of duodenal adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis reveals high cumulative risk of advanced disease. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:493–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burke CA, Beck GJ, Church JM, et al. The natural history of untreated duodenal and ampullary adenomas in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis followed in an endoscopic surveillance program. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;49 (3 Pt 1) :358–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moozar KL, Madlensky L, Berk T, et al. Slow progression of periampullary neoplasia in familial adenomatous polyposis. J Gastrointest Surg 2002;6:831–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morpurgo E, Vitale GC, Galandiuk S, et al. Clinical characteristics of familial adenomatous polyposis and management of duodenal adenomas. J Gastrointest Surg 2004;8:559–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/colorectal_screening.pd (accessed 15 April 2005).

- 46.Alarcon FJ, Burke CA, Church JM, et al. Familial adenomatous polyposis: efficacy of endoscopic and surgical treatment for advanced duodenal adenomas. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:1533–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wahab PJ, Mulder CJ, den Hartog G, et al. Argon plasma coagulation in flexible gastrointestinal endoscopy: pilot experiences. Endoscopy 1997;29:176–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Regula J, MacRobert AJ, Gorchein A, et al. Photosensitisation and photodynamic therapy of oesophageal, duodenal, and colorectal tumours using 5 aminolaevulinic acid induced protoporphyrin IX—a pilot study. Gut 1995;36:67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mlkvy P, Messmann H, Debinski H, et al. Photodynamic therapy for polyps in familial adenomatous polyposis—a pilot study. Eur J Cancer 1995;31A:1160–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loh CS, Bliss P, Bown SG, et al. Photodynamic therapy for villous adenomas of the colon and rectum. Endoscopy 1994;26:243–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abulafi AM, Allardice JT, Williams NS, et al. Photodynamic therapy for malignant tumors of the ampulla of Vater. Gut 1995;36:853–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soravia C, Berk T, Haber G, et al. Management of advanced duodenal polyposis in familial adenomatous polyposis. J Gastrointest Surg 1997;1:474–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bertoni G, Sassatelli R, Nigrisoli E, et al. Endoscopic snare papillectomy in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis and ampullary adenoma. Endoscopy 1997;29:685–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Norton ID, Geller A, Petersen BT, et al. Endoscopic surveillance and ablative therapy for periampullary adenomas. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:101–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Norton ID, Gostout CJ, Baron TH, et al. Safety and outcome of endoscopic snare excision of the major duodenal papilla. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;56:239–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Penna C, Phillips RK, Tiret E, et al. Surgical polypectomy of duodenal adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis: experience of two European centres. Br J Surg 1993;80:1027–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Penna C, Bataille N, Balladur P, et al. Surgical treatment of severe duodenal polyposis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg 1998;85:665–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Vos tot Nederveen Cappel WH, Jarvinen HJ, Bjork J, et al. Worldwide survey among polyposis registries of surgical management of severe duodenal adenomatosis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg 2003;90:705–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ruo L, Coit DG, Brennan MF, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis undergoing pancreaticoduodenal surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 2002;6:671–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Farnell MB, Sakorafas GH, Sarr MG, et al. Villous tumors of the duodenum: reappraisal of local vs. extended resection. J Gastrointest Surg 2000;4:13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chung RS, Church JM, van Stolk R. Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy: indications, surgical technique and results. Surgery 1995;117:254–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kalady MF, Clary BM, Tyler DS, et al. Pancreas-preserving duodenectomy in the management of duodenal familial adenomatous polyposis. J Gastrointest Surg 2002;6:82–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Balladur P, Penna C, Tiret E, et al. Panctreatico-duodenectomy for cancer and precancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Int J Colorectal Dis 1993;8 (3) :151–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nugent KP, Farmer KC, Spigelman AD, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect of sulindac on duodenal and rectal polyposis and cell proliferation in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg 1993;80:1618–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Debinski HS, Trojan J, Nugent KP, et al. Effect of sulindac on small polyps in familial adenomatous polyposis. Lancet 1995;345:855–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seow-Choen F, Vijayan V, Keng V. Prospective randomized study of sulindac versus calcium and calciferol for upper gastrointestinal polyps in familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg 1996;83:1763–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Richard CS, Berk T, Bapat BV, et al. Sulindac for periampullary polyps in FAP patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 1997;12:14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Phillips RK, Wallace MH, Lynch PM, et al. A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study of celecoxib, a selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor, on duodenal polyposis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut 2002;50:857–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Winde G, Schmid KW, Brandt B, et al. Clinical and genomic influence of sulindac on rectal mucosa in familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum 1997;40:1156–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maclean AR, McLeod RS, Berk T, et al. A randomized trial comparing ursodeoxycholic acid and refecoxib, a selective COX-2 inhibitor, in the treatment of advanced duodenal adenomas in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Abstract. Gastroenterology 2001;120 (suppl 1) :A254. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parker AL, Kadakia SC, Maccini DM, et al. Disappearance of duodenal polyps in Gardner’s syndrome with sulindac therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 1993;88:93–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Theodore C. Adenomas of the ampulla of vater in familial adenomatous polyposis: Christian Theodore responds. Gastroenterology 2004;126:628–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Waddell WR, Ganser GF, Cerise EJ, et al. Sulindac for polyposis of the colon. Am J Surg 1989;157:175–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wallace MH, Forbes A, Beveridge IG, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of gastric acid-lowering therapy on duodenal polyposis and relative adduct labeling in familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:1585–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vane JR, Botting RM. The mechanism of action of aspirin. Thromb Res 2003;110:255–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tsujii M, Kawano S, Tsuji S, et al. Cyclooxygenase regulates angiogenesis induced by colon cancer cells. Cell 1998;93:705–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Seno H, Oshima M, Ishikawa TO, et al. Cyclooxygenase 2- and prostaglandin E(2) receptor EP(2)-dependent angiogenesis in Apc(Delta716) mouse intestinal polyps. Cancer Res 2002;62:506–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chapple KS, Scott N, Guillou PJ, et al. Interstitial cell cyclooxygenase-2 expression is associated with increased angiogenesis in human sporadic colorectal adenomas. J Pathol 2002;198:435–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sheng H, Shao J, Morrow JD, et al. Modulation of apoptosis and Bcl-2 expression by prostaglandin E2 in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res 1998;58:362–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sato N, Maehara N, Goggins M. Gene expression profiling of tumor-stromal interactions between pancreatic cancer cells and stromal fibroblasts. Cancer Res 2004;64:6950–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang X, Morham SG, Langenbach R, et al. Malignant transformation and antineoplastic actions of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on cyclooxygenase-null embryo fibroblasts. J Exp Med 1999;190:451–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hanif R, Pittas A, Feng Y, et al. Effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on proliferation and on induction of apoptosis in colon cancer cells by a prostaglandin-independent pathway. Biochem Pharmacol 1996;52:237–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thompson WJ, Piazza GA, Li H, et al. Exisulind induction of apoptosis involves guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate phosphodiesterase inhibition, protein kinase G activation, and attenuated beta-catenin. Cancer Res 2000;60:3338–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Smith ML, Hawcroft G, Hull MA. The effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on human colorectal cancer cells: evidence of different mechanisms of action. Eur J Cancer 2000;36:664–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Koh TJ, Bulitta CJ, Fleming JV, et al. Gastrin is a target of the beta-catenin/TCF-4 growth-signaling pathway in a model of intestinal polyposis. J Clin Invest 2000;106:533–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Huang Y, He Q, Hillman MJ, et al. Sulindac sulfide-induced apoptosis involves death receptor 5 and the caspase 8-dependent pathway in human colon and prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res 2001;61:6918–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Baek SJ, Kim KS, Nixon JB, et al. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors regulate the expression of a TGF-beta superfamily member that has proapoptotic and antitumorigenic activities. Mol Pharmacol 2001;59:901–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Weyant MJ, Carothers AM, Bertagnolli ME, et al. Colon cancer chemopreventive drugs modulate integrin-mediated signaling pathways. Clin Cancer Res 2000;6:949–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shureiqi I, Lippman SM. Lipoxygenase modulation to reverse carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 2001;61:6307–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Forman BM, Chen J, Evans RM. Hypolipidemic drugs, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and eicosanoids are ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and delta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;94:4312–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gupta RA, Tan J, Krause WF, et al. Prostacyclin-mediated activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97:13275–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lehmann JM, Lenhard JM, Oliver BB, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and gamma are activated by indomethacin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Biol Chem 1997;272:3406–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kliewer SA, Sundseth SS, Jones SA, et al. Fatty acids and eicosanoids regulate gene expression through direct interactions with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;94:4318–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]