There is a rare cause of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (CIPO) characterised by a lymphocytic infiltrate in the muscle of the intestine, which is called idiopathic lymphocytic leiomyositis. Few cases have been reported and prognosis is very poor. We present a case with a comparatively benign evolution, showing good response to immunosuppressive therapy.

The patient was a healthy 16 year old female who presented with a crisis of postprandial bloating followed by diarrhoea and vomiting. During the following months she lost 10 kg in weight and any attempt at oral feeding resulted in severe abdominal distension and vomiting. Therefore, total parenteral nutrition was finally prescribed. Plain abdominal film and small bowel follow through indicated huge dilatation of the small intestine with air fluid levels. Gastroscopy and colonoscopy were normal, as were mucosal biopsies.

Human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis A, B, and C virus, cytomegalovirus, Salmonella, Leptospira, Coxiella, Borrelia burgdorferii, Treponema pallidum, faecal cultures and parasites, tuberculin skin test, and cultures for Mycobacterium tuberculosis were all negative, as were autoimmune markers.

Intestinal manometry showed severe hypomotility in the duodenum and jejunum. Laparotomy was performed, showing a very dilated small intestine and colon, plenty of liquid, with thinned walls. Full thickness intestinal biopsies were taken.

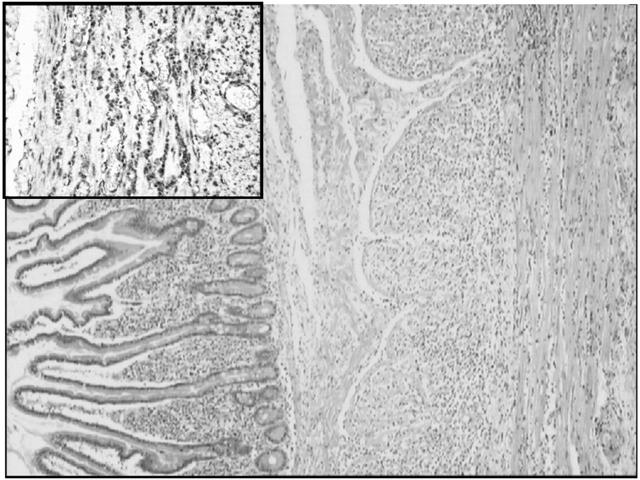

Histologically, the intestinal mucosa and submucosa were normal. Both muscle layers presented with a heavy diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate (fig 1 ▶), composed of small CD3 and CD8 lymphocytes (no CD20). Muscular fibres were atrophic with some fibrosis. The submucosal and myenteric plexuses were normal and the muscularis mucosae was not affected. Immunohistochemical stain for smooth muscle actin was negative or faintly positive in the muscularis propria, with preservation of a thin ribbon at the innermost portion of the circular layer. A final diagnosis of lymphocytic intestinal leiomyositis was made.

Figure 1.

Full thickness biopsy of the small intestine with haematoxylin-eosin. The section shows a normal mucosal layer of jejunum without atrophy or excessive amounts of round cells. The muscularis mucosae is also normal. In contrast, the muscularis propria shows a heavy lymphocytic infiltrate (haematoxylin-eosin). Insert: immunohistochemical stain for CD8 lymphocytes in the muscularis propria.

The patient started prednisone 1 mg/kg/day and azathioprine 1 mg/kg/day. She was hospitalised for eight months during the first year due to multiple complications. Complete response was not obtained until one year later when the azathioprine dose reached 2 mg/kg/day, and budesonide 9 mg/day was added. Prednisone was then discontinued and abdominal films became normal.

Two years after diagnosis she has not needed hospitalisation or parenteral nutrition in the last 15 months, and has followed a normal oral diet.

Review of the world literature on CIPO associated with lymphoid infiltrates in the gut revealed only 12 cases, as shown in table 1 ▶. A critical review could restrict the number to three, plus the present case, as true lymphocytic enteric leiomyositis.

Table 1.

Clinical and histological features of our present case and cases in the literature

| Sex/age (y) | Histological features | Treatment | Evolution | True lymphocytic intestinal leiomyositis | |

| Present case | F 16 | T lymphocytic infiltrate in muscularis propria | Steroids and later budesonide. Azathioprine | Mild symptoms, oral nutrition 2 y later | Yes |

| Nezelof5 | M 6 mo | Mononuclear infiltrate in muscularis propria | Steroids | Death 4 y later | Yes |

| Ruuska6 | M 2 | Predominant T lymphocytic infiltrate | Steroids, azathioprine, ciclosporin | Total PN | Yes |

| Mann7 | M 47 | Chronic inflammatory infiltrate + fibrosis of longitudinal muscle | NR | Death 2 y later | Probably yes |

| Rigby3 | F 27 | Predominant fibrosis of the circular layer | Immunosuppression | Oral diet plus gastrostomy feeds. Alive at 21 months | Probably no |

| Giniès4 | F 6 mo | Very polymorphic infiltrate: lymphocytes, plasmocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils | Steroids | Oral nutrition. Normal weight and height | No (probably B lymphocytes) |

| McDonald1 cases 1/2/3/4 | F 51/F 21/ F 29/F 18 | Mucosa predominantly affected | Cyclophosphamide and steroids/steroids/ antibiotics/cisapride | Mild symptoms at 9 y/PN one year later/NR/NR | Probably no (B lymphocytes) |

| Arista-Nasr2 cases 1/2/3 | F 23/F 29/ F 23 | Mucosa predominantly affected | Cyclophosphamide/ tetracycline, tinidazol, PE/tetracycline, steroids, chemotherapy. | Death from inanition/death from inanition/alive, severe inanition | Probably no (B lymphocytes) |

M, male; F, female; NR, not reported; PN, parenteral nutrition; PE, pancreatic enzymes.

McDonald’s1 and Arista-Nasr’s2 cases showed predominantly mucosal infiltrate with secondary extension into deeper layers. Our case showed a particularly affected muscle with a respected mucosa. In Rigby’s case,3 the muscular layer seemed to show fibrosis rather than inflammation. Our case showed a homogeneous lymphocytic T infiltrate which is different from the polymorphic infiltrate of Giniès’ case.4

We believe that only the cases presented by Nezelof,5 Ruuska,6 and perhaps Mann’s7 fourth case, are truly similar to ours. The lymphocytic infiltrate was similar and there were degenerative changes of the smooth muscle. Clinically, these three cases shared a very poor prognosis: two patients died and one was on parenteral nutrition, despite immunosuppressive therapy. This treatment was employed in at least two of the patients. Our case had a better outcome, with azathioprine and budesonide allowing discontinuation of prednisone.

In CIPO, if full thickness biopsies8 are typical of lymphocytic leiomyositis, based on what little information is available, it is reasonable to start high dose steroids and another form of immunosuppression. Based on our case, we would recommend budesonide 9 mg/day and azathioprine 2 mg/kg/day while tapering off conventional steroids, if clinical response continues.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.McDonald GB, Schuffler MD, Kadin ME, et al. Intestinal pseudoobstruction caused by diffuse lymphoid infiltration of the small intestine. Gastroenterology 1985;89:882–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arista-Nasr J, González-Romo M, Keirns C, et al. Diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of the small intestine with damage to nerve plexus. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1993;117:812–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rigby SP, Schott JM, Higgens CS, et al. Dilated stomach and weak muscles. Lancet 2000;356:1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giniès JL, François H, Joseph MG, et al. A curable cause of chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction in children: idiopathic myositis of the small intestine. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1996;23:426–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nezelof C, Vivien E, Bigel P, et al. La myosite idiopathique de l’intestin grêle. Arch Fr Pediatr 1985;42:823–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruuska TH, Karikoski R, Smith VV, et al. Acquired myopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction may be due to autoimmune enteric leiomyositis. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1133–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann SD, Debinski HS, Kamm MA. Clinical characteristics of chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction in adults. Gut 1997;41:675–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Giorgio R, Sarnelli G, Corinaldesi R, et al. Advances in our understanding of the pathology of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Gut 2004;53:1549–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]