The incidence of acute pancreatitis is increasing in the UK,1 with a current hospital admission rate of 9.8 per year per 100 000 population.1 However, there has only been a marginal decrease in the overall one year case fatality rate, from 12.7% in 1975–86 to 11.8% in 1987–98.1 Gall stones and alcohol are the main aetiological factors for acute pancreatitis.2 Nearly 25% of episodes of acute pancreatitis are severe3 and approximately 45% of these are due to gall stones.2

The UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis were formulated and released by the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) in 1998.4 MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane databases were searched to find recent evidence in the management of acute pancreatitis. The search terms included pancreatitis (MeSH), sphincterotomy-endoscopic (MeSH), cholangiopancreatography-magnetic-resonance (MeSH), acute NEAR pancreatitis (text), MRCP (text), ERCP AND sphincterotomy (text).

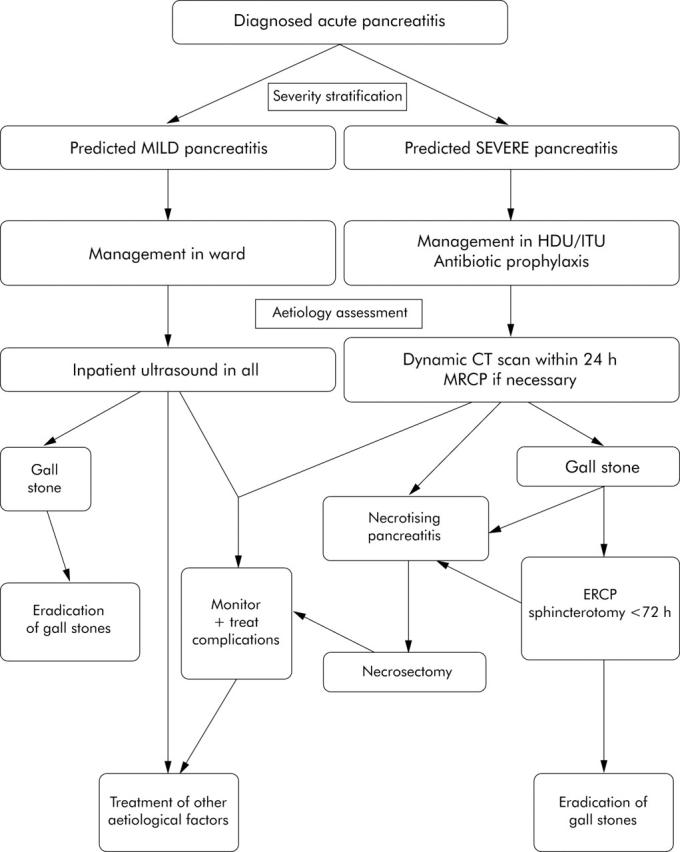

A management plan, modified from the BSG guidelines in light of the new evidence available since its release in 1998, is proposed in fig 1 ▶. Firstly, acute pancreatitis is stratified according to severity. Glasgow-Imrie scoring together with C reactive protein are recommended by the BSG for stratification of severity of acute pancreatitis.4 However, with the availability of one stop tests, such as urinary trypsinogen activation peptide,5 and with the likelihood of mild acute pancreatitis transforming into severe acute pancreatitis being rare,6 severity stratification of pancreatitis can now be performed on admission.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for the management of acute pancreatitis. MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; CT, computed tomography; HDU, high dependency unit; ITU, intensive therapy unit.

The next step is to determine aetiology. Imaging to find aetiology should be performed within 24 hours, in contrast with the BSG recommendations of a CT scan between three and 10 days. The rationale behind imaging within 24 hours is to facilitate early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and sphincterotomy, as there is strong evidence that ERCP and sphincterotomy performed less than 72 hours decreases the complication rate in acute severe gall stone pancreatitis.7 This imaging, within 24 hours during the acute resuscitation phase, is made possible because of the shorter time to perform spiral computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen,8 which has a high sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing choledocholithiasis.9 If the aetiology is still unknown after the CT scan, a magnetic resonance cholangio(pancreato)gram (MRCP) may be performed, as this has a higher sensitivity than the CT scan in the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis.10

A simple calculation based on the incidence of pancreatitis (9.8 per year per 100 000 population),1 the incidence of severe pancreatitis (approximately 25%),3 and the incidence of gall stones as the aetiological factor in acute severe pancreatitis (45%)2 reveals that severe acute gall stone pancreatitis has an incidence of approximately 1.1 per year per 100 000 population. In a NHS trust with a catchment population of 500 000, it is only five additional emergency ERCP with sphincterotomies annually. This appears to be a feasible option. However, if ERCP with sphincterotomy cannot be performed within 72 hours in a hospital, patients should be transferred early (after stabilising the vital signs) to a hospital where such facilities are available.

In conclusion, a review of the UK guidelines is recommended following evidence that morbidity is less in early ERCP and sphincterotomy (<72 hours) in severe gall stone pancreatitis. Also, because of the accuracy of MRCP in the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis and the new one stop tests available for severity stratification of acute pancreatitis on admission, we recommend one stop tests for severity stratification of pancreatitis and imaging within 24 hours of admission in acute pancreatitis in order to find the aetiology so that ERCP and sphincterotomy can be performed within 72 hours.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Goldacre MJ, Roberts SE. Hospital admission for acute pancreatitis in an English population, 1963–98: database study of incidence and mortality. BMJ 2004;328:1466–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gloor B, Müller CA, Worni M, et al. Late mortality in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg 2001;88:975–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winslet M, Hall C, London NJ, et al. Relation of diagnostic serum amylase levels to aetiology and severity of acute pancreatitis. Gut 1992;33:982–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.British Society of Gastroenterology. United Kingdom guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut 1998;42 (suppl 2) :S1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neoptolemos JP, Kemppainen EA, Mayer JM, et al. Early prediction of severity in acute pancreatitis by urinary trypsinogen activation peptide: a multicentre study. Lancet 2000;355:1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley EL III. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg 1993;128:586–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayub K, Imada R, Slavin J. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in gallstone-associated acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;issue 3 :CD003630. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Schoepf UJ, Becker CR, Hofmann LK, et al. Multislice CT angiography. Eur Radiol 2003;13:1946–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabada GT, Sarría O, Martínez BMT, et al. Helical CT cholangiography in the evaluation of the biliary tract: application to the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis. Abdom Imaging 2002;27:61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soto JA, Alvarez O, Múnera F, et al. Diagnosing bile duct stones: comparison of unenhanced helical CT, oral contrast-enhanced CT cholangiography, and MR cholangiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000;175:1127–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]