Methotrexate (MTX) is widely used not only as a chemotherapeutic agent for the treatment of many cancers but also as an anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agent. MTX treatment is often accompanied by side effects such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, stomatitis, gastrointestinal ulceration, and mucositis. The therapeutic use of MTX has been limited by its toxicity for proliferating cells, especially the rapidly dividing cells of intestinal crypts. MTX inhibited intestinal epithelial proliferation and induced apoptosis in the small intestinal crypts.1,2 However, there is little effective treatment to reduce the MTX induced gastrointestinal toxicity.

Garlic (Allium sativum) has various biological properties such as antimicrobial and antithrombotic activities, immune system enhancement, and antitumour potential.3 Aged garlic extract (AGE) and its constituents have been shown to prevent oxidative injury in endothelial cells4 and suppress cancer cell growth.5 We have previously shown that AGE protects the small intestine of rats from MTX induced injury.6,7 Therefore, AGE seems to act on tumour cells and normal intestinal cells in different ways.

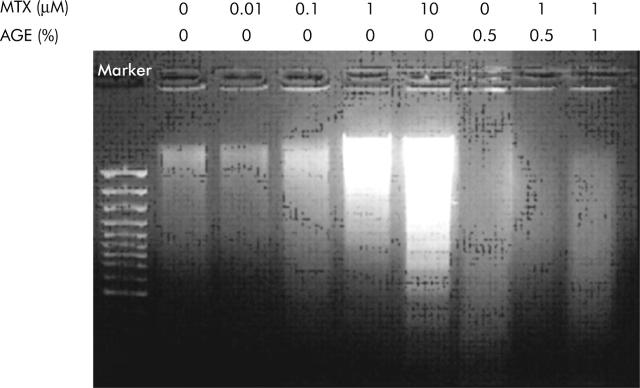

IEC-6 is an immortalised epithelial cell line derived from neonatal rat ileum which has been extensively used as an in vitro intestinal model.8 Exposure of IEC-6 cells to MTX significantly decreased cell viability, depending on exposure time and MTX concentration, which was prevented by AGE. IEC-6 cells exposed to 1 μM MTX for 72 h showed nucleus condensation by Hoechst staining. Addition of AGE (0.5%) to the medium containing 1 μM MTX inhibited MTX induced nucleus condensation. DNA of IEC-6 cells treated with MTX and/or AGE was isolated and analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis (fig 1 ▶). MTX caused DNA fragmentation while AGE inhibited MTX induced fragmentation of DNA. Caspase-3 activity in IEC-6 cells exposed to MTX was significantly upregulated. AGE (0.5%) significantly reduced activation of caspase-3 induced by MTX. Caspase-3, a key enzyme for execution of apoptosis in many instances, also plays a central role for MTX induced apoptosis in IEC-6 cells. MTX induced the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol, indicating a prominent downstream manifestation of the evolution of apoptotic cell death. Interestingly, AGE prevented the release of cytochrome c. These results indicate that MTX induced the death of IEC-6 cells through apoptosis, consistent with the previous observation that MTX induced apoptosis in the small intestine.2

Figure 1.

Effect of aged garlic extract (AGE) on DNA fragmentation in methotrexate (MTX) treated IEC-6 cells. IEC-6 cells were treated with various concentrations of MTX and AGE for 72 h. DNA was extracted and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

In vivo, in rats given MTX, AGE protected the small intestine from MTX induced injury.6,7 In in vivo IEC-6 cells originating from crypt cells of the rat small intestine, MTX induced loss of viable IEC-6 cells was almost completely prevented by the presence of more than 0.1% AGE. Chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation, caspase-3 activation, and cytochrome c release, which were caused by MTX, were preserved to control levels by the presence of AGE. These results suggest that AGE inhibits MTX induced apoptosis in IEC-6 cells. The protective effect of AGE may be associated with depression of oxidative stress as AGE has the effect of antioxidation.9 On the other hand, oxidative stress was shown to be involved in MTX induced toxicity of the small intestine.10

These cell culture studies indicate that AGE protects IEC-6 cells from MTX induced injury. The protective effect of AGE found in IEC-6 cells may possibly occur through the antiapoptosis action of AGE, newly found in this study, and can explain the reason why AGE administered to rats protects the small intestine from the injury induced by MTX administration.6,7 AGE may be useful for cancer chemotherapy with MTX because it reduces MTX induced intestinal injury.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Taminiau JA, Gall DG, Hamilton JR. Response of the rat small-intestine epithelium to methotrexate. Gut 1980;21:486–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verburg M, Renes IB, Meijer HP, et al. Selective sparing of goblet cells and paneth cells in the intestine of methotrexate-treated rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2000;279:G1037–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal KC. Therapeutic actions of garlic constituents. Med Res Rev 1996;16:111–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ide N, Lau BH. Garlic compounds protect vascular endothelial cells from oxidized low density lipoprotein-induced injury. J Pharm Pharmacol 1997;49:908–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shirin H, Pinto JT, Kawabata Y, et al. Antiproliferative effects of S-allylmercaptocysteine on colon cancer cells when tested alone or in combination with sulindac sulfide. Cancer Res 2001;61:725–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horie T, Awazu S, Itakura Y, et al. Alleviation by garlic of antitumor drug-induced damage to the intestine. J Nutr 2001;131:1071–4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horie T, Matsumoto H, Kasagi M, et al. Protective effect of aged garlic extract on the small intestinal damage of rats induced by methotrexate administration. Planta Med 1999;65:545–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li T, Ito K, Horie T. Transport of fluorescein methotrexate by multidrug resistance-associated protein 3 in IEC-6 cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2003;285:G602–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horie T, Murayama T, Mishima T, et al. Protection of liver microsomal membranes from lipid peroxidation by garlic extract. Planta Med 1989;55:506–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyazono Y, Gao F, Horie T. Oxidative stress contributes to methotrexate-induced small intestinal toxicity in rats. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004;39:1119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]