Abstract

Background: Diabetic gastroparesis is a disabling condition with no consistently effective treatment. In animals, ghrelin increases gastric emptying and reverses postoperative ileus. We present the results of a double blind, placebo controlled, crossover study of ghrelin in gastric emptying in patients with diabetic gastroparesis.

Methods: Ten insulin requiring diabetic patients (five men, six type I) referred with symptoms indicative of gastroparesis received a two hour infusion of either ghrelin (5 pmol/kg/min) or saline on two occasions. Blood glucose was controlled by euglycaemic clamp. Gastric emptying rate (GER) was calculated by real time ultrasound following a test meal. Blood was sampled for ghrelin, growth hormone (GH), and pancreatic polypeptide (PP) levels. Cardiovagal neuropathy was assessed using the Mayo Clinic composite autonomic severity score (range 0 (normal)–3).

Results: Baseline ghrelin levels were mean 445 (SEM 36) pmol/l. Ghrelin infusion achieved a peak plasma level of 2786 (188) pmol/l at 90 minutes, corresponding to a peak GH of 70.9 (19.8) pmol/l. Ghrelin increased gastric emptying in seven of 10 patients (30 (6)% to 43 (5)%; p = 0.04). Impaired cardiovagal tone correlated inversely with peak postprandial PP values (p<0.05) but did not correlate with GER.

Conclusions: Ghrelin increases gastric emptying in patients with diabetic gastroparesis. This is independent of vagal tone. We propose that analogues of ghrelin may represent a new class of prokinetic agents.

Keywords: ghrelin, diabetic gastroparesis, pancreatic polypeptide

Delayed gastric emptying occurs in up to 50% of patients with chronic diabetes and is associated with significant impairments in both quality of life and diabetic control. While this delay is not always clinically apparent, the range of gastrointestinal symptoms may include early satiety, nausea, vomiting, regurgitation, fullness, and bloating.1 Impaired gastric emptying in diabetic patients can be associated with a number of possible metabolic consequences: poor glycaemic control, increased risk of postprandial hypoglycaemia, and variable drug absorption. At its worst, gastroparesis can lead to intractable vomiting and an inability to feed, and carries a poor prognosis.2

Diabetic gastroparesis remains an extremely difficult condition to treat effectively. Present management involves the empirical use of prokinetic drugs such as domperidone, metoclopramide, and cisapride.2,3 Erythromycin, which has motilin analogue properties, is also of some value in a subset of patients.4 The effects of these drugs however are unpredictable. Short term administration may accelerate gastric emptying but not necessarily improve symptoms. Furthermore, with chronic administration, the short term benefits are frequently lost.5 One possible explanation for this lack of sustained response to treatment is that gastroparesis may be aetiologically associated with progressive autonomic neuropathy. Assessing autonomic tone to the gut in diabetic patients has primarily been through assessment of cardiovagal autonomic parameters.6 An alternative, more gut specific, assessment of autonomic tone is by measurement of plasma pancreatic polypeptide (PP) in response to sham feeding.7

The discovery in 1999 of the gastric derived peptide ghrelin presents us with another potential gastric prokinetic agent.8 Human ghrelin exhibits 36% identity with motilin, while their respective receptors exhibit 50% homology.9 Ghrelin levels rise prior to eating and fall postprandially, and this hormone may have a role in meal initiation10 and energy homeostasis.11 In addition to increasing food intake, ghrelin administration in animals has been shown to increase gastric emptying9,12 and induce fasting motor activity of the gastrointestinal tract.13 It has also been demonstrated that ghrelin induces the migrating motor complex in fed rats and increases the frequency of the migrating motor complex in the fasted state, suggesting potential as an enterokinetic.13 In the rat, ghrelin stimulates motility in the small intestine through intrinsic cholinergic neurones14 but does not appear to affect colonic motility.15

Parenteral administration of ghrelin in humans increases appetite and food intake,11,16 stimulates GH secretion, and has positive inotropic cardiovascular effects.17 There have been no reported serious side effects in any of these studies, which supports the safety of its administration in humans. In view of the controversy over the clinical effect of known gastrokinetic drugs,18 we report a “proof of concept” study investigating the effect of ghrelin in patients with diabetic gastroparesis. We present the results of a double blind, placebo controlled, crossover study (conducted on secondary and tertiary referral patients), with efficacy being assessed both in terms of gastric emptying and autonomic function.

METHODS

Patient selection

The aim of the study was to investigate whether ghrelin improved gastric emptying in patients with diabetic gastroparesis. The primary outcome was change in gastric emptying rate (GER). The study was approved by the Northwick Park and St Mark’s committee and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ten diabetic patients (five men, mean age 46 (range 36–63) years) were recruited from the outpatients department of a secondary and tertiary referral specialist gastroenterology hospital where they had been referred with persistent upper gastrointestinal symptoms, including vomiting. Six were type I diabetics and all were insulin treated. Since the accuracy of gastric emptying studies has been questioned by some authors,19,20 recruitment to this trial was based primarily on symptoms. Recently, the symptom of bloating has been identified as a reliable predictor of gastroparesis.21 Subjects were therefore recruited on the presence of bloating plus two other upper gastrointestinal symptoms on a validated questionnaire.22

All patients had undergone normal upper gastrointestinal endoscopies within six months of enrolment into the study to rule out gastric outlet obstruction or other pathology. Based on a negative CLO test, all patients were Helicobacter pylori negative at the time of the study (three after previous eradication therapy which had been confirmed with subsequent urea breath test before enrolment). All patients had a negative hydrogen breath test for bacterial overgrowth. Patients were ask to stop using proton pump inhibitors, any prokinetic medication, and any autonomically active drugs for at least one week prior to the study. Clinical data were collected for all subjects, including body mass index (BMI), duration of diabetes, and presence of diabetic complications. Symptoms of peripheral neuropathy were assessed using a validated questionnaire.23 Baseline creatinine, HbA1c, urea and electrolytes, full blood count, and thyroid function were all assessed.

Test meal

The test meal of rice pudding (330 kcal, 10% protein, 58% carbohydrate, 32% fat) was given at t = 60 minutes and subjects were asked to consume it within five minutes.

Ultrasound assessment of gastric emptying rate (GER)

The methods for this procedure have been previously described and have been validated in healthy controls and diabetic patients, correlating well with scintigraphic measurement.24,25 Real time ultrasound scanning was carried out using a 5.2 mHz curved array probe using SonoSite 180plus (SonoSite, Herts, UK). Gastric emptying was monitored indirectly by determining the longitudinal (D1) and anteroposterior (D2) diameters of a single section of gastric antrum, using the abdominal aorta and the left lobe of the liver as internal landmarks.24 For both the longitudinal (D1) and anteroposterior (D2) diameters, three measurements were done using the mean values of the longitudinal (D1mean) and anteroposterior (D2mean) diameters to calculate the antral area. The antral cross sectional area (Aantrum) was calculated in all subjects using the formula:

Aantrum = π×D1mean×D2mean/4

Measurements were made at 15 and 90 minutes postprandially. GER was estimated and expressed as the percentage reduction in cross sectional area from 15 to 90 minutes, calculated as follows:

GER = [(A area90min/A area15min)−1]×100

All of the ultrasound measurements were made by a single radiologist (ST) who was also blinded to the infusion order.

Glycaemic clamp

Blood glucose was maintained between 5 and 8 mmol/l in all subjects throughout each study. Patients omitted their dose of insulin on the morning of the study. Human Actrapid (Novo Nordisk, Crawley, West Sussex, UK), used in all patients (apart from one patient who used Hypurin Porcine neutral (CP)), was diluted in saline and infused at a constant basal rate, equal to the patient’s total daily insulin dose divided by 24. To maintain euglycaemia, saline was infused at 80 ml/h together with a variable infusion of 20% glucose to maintain blood glucose at concentrations of 5–8 mmol/l according to blood glucose measurements using a glucometer (Medisense Optimum; Abbott Laboratories Ltd, Maidenhead, UK) every 15 minutes.

Preparation of ghrelin

Synthetic human ghrelin was purchased from Bachem (UK) Ltd (Merseyside, UK). The Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay test for pyrogen was negative (Associates of Cape Cod, Liverpool, UK), and the peptide was sterile on culture. Vials of ghrelin and saline were indistinguishable visually; they were labelled by subject and infusion numbers and stored in a sealed container.16 Patients and investigators were blinded to the infusion order until study completion.

Infusions

The study was a randomised, double blinded, crossover design. The order of infusions was randomised using the statistics package Sigmastat version 2.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Five patients had ghrelin first and five had saline first. On infusion days, patients attended hospital after an eight hour fast and had three intravenous cannulae sited in their forearms at 0800 h. Ghrelin was infused at a rate of 5 pmol/kg/min, which has been shown previously to stimulate appetite and growth hormone (GH) secretion.11,16 Each infusion continued for 120 minutes. Subjects were continuously attached to a cardiac monitor with blood pressure and heart rate recorded every 30 minutes (Dinamap; GE Medical Systems, Freiburg, Germany).

Autonomic assessment

The degree of autonomic neuropathy was assessed using an adapted Mayo Clinic composite autonomic severity score (CASS).26 CASS assesses postganglionic pseudomotor, adrenergic, and cardiovagal function: in the study, we assessed the latter two. Sympathetic adrenergic function was assessed by beat to beat blood pressure and heart rate responses to head-up tilt and the Valsalva manoeuvre (score 0–4). Cardiovagal function was evaluated by heart rate responses to deep breathing and the Valsalva manoeuvre (score 0–3). An increased score is correlated with loss of function.

Blood sampling

Blood samples were drawn at −75, 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 minutes during the study. Samples (10 ml) were collected into plastic lithium heparin tubes containing 0.6 mg aprotonin. Samples were immediately centrifuged, and plasma separated and stored at −80°C until assay.

Plasma GH concentration

Plasma GH was analysed using Advantage automated chemiluminescent immunoassay (Nichols Institute Diagnostics, San Juan Capistrano, California, USA).

Plasma PP concentrations

Plasma PP concentrations were measured with a specific and sensitive radioimmunoassay, as previously described.27 The assay cross reacted fully (100%) with human PP and did not cross react with any other member of the PP family or gastrointestinal hormone. Antisera against human PP was produced in rabbits and used at a final dilution of 1: 560 000. 125I PP was prepared by the iodogen method and purified by high pressure liquid chromatography. The specific activity of the 125I PP label was 54 Bq/fmol. The assay was performed in a total volume of 0.7 ml of 0.06 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, containing 0.3% bovine serum albumin. The assay was incubated for three days at 4°C before separation of the free and antibody bound label by charcoal absorption. The detection limit of the assay was 3.5 pmol/l and the intra-assay coefficient of variation was 5.7%. All samples were measured in one assay to avoid interassay variation.

Plasma ghrelin

Ghrelin-like immunoreactivity was measured with a specific and sensitive radioimmunoassay, as previously described.28 Briefly, the assay cross reacts fully (100%) with both octanoyl and desoctanoyl ghrelin and does not cross react with any other known gastrointestinal or pancreatic hormone. The antisera (SC-10368) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and used at a final dilution of 1:50 000. 125I ghrelin was prepared with Bolton and Hunter reagent (Amersham International, UK) and purified by high pressure liquid chromatography using a linear gradient from 10% to 40% acetonitrile, 0.05% TFA over 90 minutes. The specific activity of the ghrelin label was 48 Bq/fmol. The assay was performed in a total volume of 0.7 ml of 0.06 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.2 containing 0.3% bovine serum albumin, and was incubated for three days at 4°C before separation of free and bound antibody label by charcoal absorption. The assay detected changes of 20 pmol/l of plasma ghrelin with a 95% confidence limit. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 5.5%. All samples were measured in one assay to avoid interassay variation.

Symptom scores

On both infusion days, visual analogue scores of the symptoms of bloating, hunger, and nausea were assessed at baseline and thereafter at 30 minute intervals until 180 minutes.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS software version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Differences in peptide levels were measured by analysis of variance. GER data were found to be normally distributed. GER results from the first study day were subtracted from the results of the second study day to remove the effect of order from the analysis. The treatment effect was then evaluated by comparing the differences between treatment orders using a two sample test. Correlations were carried out using Pearson’s correlation. Symptom scores were assessed using analysis of variance. GER and peptide data are presented as mean (SEM) unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS

Patients

Ten patients were studied on two separate occasions. The demographics of the patient group are outlined in table 1 ▶.

Table 1.

Demographic details and diabetic history

| Patient No | Sex | Age (y) | BMI (kg/m2) | Duration diabetes (y) | HbA1C (%) | Creatinine (mmol/l) | Retinopathy | Peripheral neuropathy score | Cardiovagal function score (0–3) | Adrenergic function score (0–4) |

| 1 | F | 51 | 25.6 | 25 | 11 | 98 | No | 9 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | F | 48 | 33.6 | 8 | 10 | 97 | Yes | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | F | 45 | 22.3 | 28 | 9 | 110 | Yes | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | F | 63 | 22.6 | 22 | 7.9 | 85 | Yes | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 5 | M | 56 | 31.1 | 21 | 12 | 83 | Yes | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | M | 39 | 23.6 | 10 | 6.8 | 123 | Yes | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | F | 36 | 25.6 | 12 | 6.2 | 103 | Yes | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| 8 | M | 43 | 25.9 | 10 | 11 | 78 | Yes | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 9 | M | 51 | 35.4 | 22 | 9.2 | 164 | Yes | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 10 | M | 44 | 23.8 | 5 | 11 | 104 | No | 2 | 1 | 2 |

BMI, body mass index.

Gastric emptying

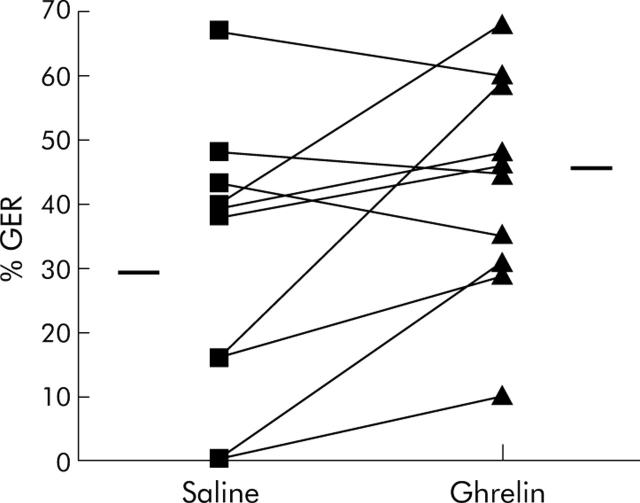

GER did not correlate with duration of diabetes (r = −0.128, p = 0.807) or HbA1C (r = 0.48, p = 0.161). Ghrelin significantly increased gastric emptying in seven of 10 patients, from 30 (6)% to 43 (5)% (p = 0.04) (fig 1 ▶). Figure 1 ▶ shows that the three patients with the highest levels of gastric emptying with saline infusion had the least response to ghrelin.

Figure 1.

Effect of ghrelin on gastric emptying rate (GER) in diabetic gastroparesis. The horizontal bars represent the mean GER during each infusion. Ghrelin increased gastric emptying from 30 (6)% to 43 (5)%. Patients with the highest levels of gastric emptying with saline demonstrated the least effect with ghrelin infusion.

Cardiovagal autonomic neuropathy (CAN) score

CAN scores are included in table 1 ▶. There was an inverse correlation between peak PP level and CAN score during both saline (r = −0.702, p = 0.024) and ghrelin (r = −0.851, p = 0.002) infusions (fig 2 ▶). There was no correlation between cardiovagal score and peak GH following ghrelin infusion (r = −0.179, p = 0.620). There was no correlation between GER with ghrelin and CAN score (r = −0.089, p = 0.807).

Figure 2.

Correlation between cardiovagal neuropathy score and peak pancreatic polypeptide (PP) level during ghrelin infusion. There was an inverse correlation between peak PP level and cardiac autonomic neuropathy score during both saline (r = −0.702, p = 0.024) and ghrelin (r = −0.851, p = 0.002) infusions.

Plasma ghrelin and PP

Effect of ghrelin and saline infusion

Mean fasting plasma ghrelin concentration was 445 (36) pmol/l (mean (SEM)), with levels ranging from 120 to 1020 pmol/l. Fasting ghrelin levels inversely correlated with BMI (r = −0.71, p = 0.023). Fasting ghrelin levels correlated inversely with BMI (r = −0.71, p = 0.023). Ghrelin infusion achieved steady state at 90 minutes (table 2 ▶). GH levels did not increase significantly above baseline during saline infusion (table 3 ▶).

Table 2.

Plasma ghrelin levels with saline and ghrelin infusions at 0, 60, 90, 120, and 180 minutes

| Treatment | Ghrelin (pmol/l) | ||||

| 0 min (infusion starts) | 60 min (pre-meal) | 90 min (post-meal) | 120 min | 180 min | |

| Saline | 404 (64) | 383 (73) | 447 (67) | 419 (64) | 399 (72) |

| Ghrelin | 431 (70) | 2543 (147) | 2786 (188) | 2772 (234) | 1717 (131) |

| p Value | 0.29 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Table 3.

Plasma growth hormone (GH) levels with saline and ghrelin infusions at 0, 90, 120, and 180 minutes

| Treatment | GH (pmol/l) | |||

| 0 min (infusion starts) | 90 min | 120 min | 180 min | |

| Saline | 1.6 (1.3) | 6.9 (5) | 2.5 (1.8) | 1.5 (0.8) |

| Ghrelin | 3.5 (2.7) | 70.9 (19.8) | 45.4 (13) | 10.6 (3.4) |

| p Value | 0.18 | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.02 |

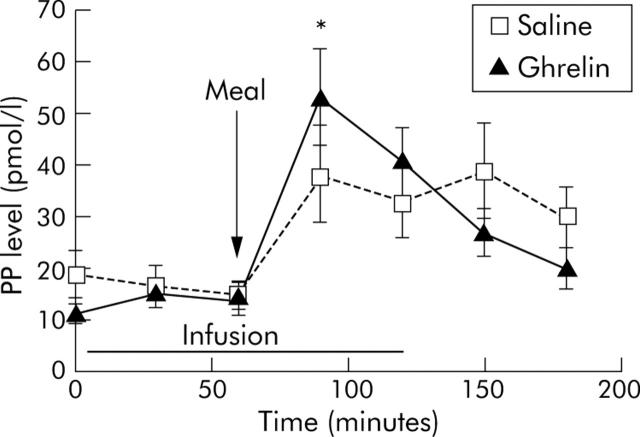

Effect of test meal

Ghrelin levels during euglycaemia did not change significantly following the test meal. Plasma PP peaked within 30 minutes of the meal and did not differ between the two infusions (p = 0.07) (fig 3 ▶). Peak plasma PP did not correlate with GER during either saline (r = −0.172, p = 0.634) or ghrelin (r = 0.062, p = 0.864) administration.

Figure 3.

Effect of ghrelin and saline infusions on pancreatic polypeptide (PP) release. PP levels increased significantly within 30 minutes of the test meal in all patients during both infusions (*p<0.05). There were no significant differences in peak PP levels between the saline and ghrelin study days (p>0.05). The arrow represents the test meal, and the straight bar the period of infusion.

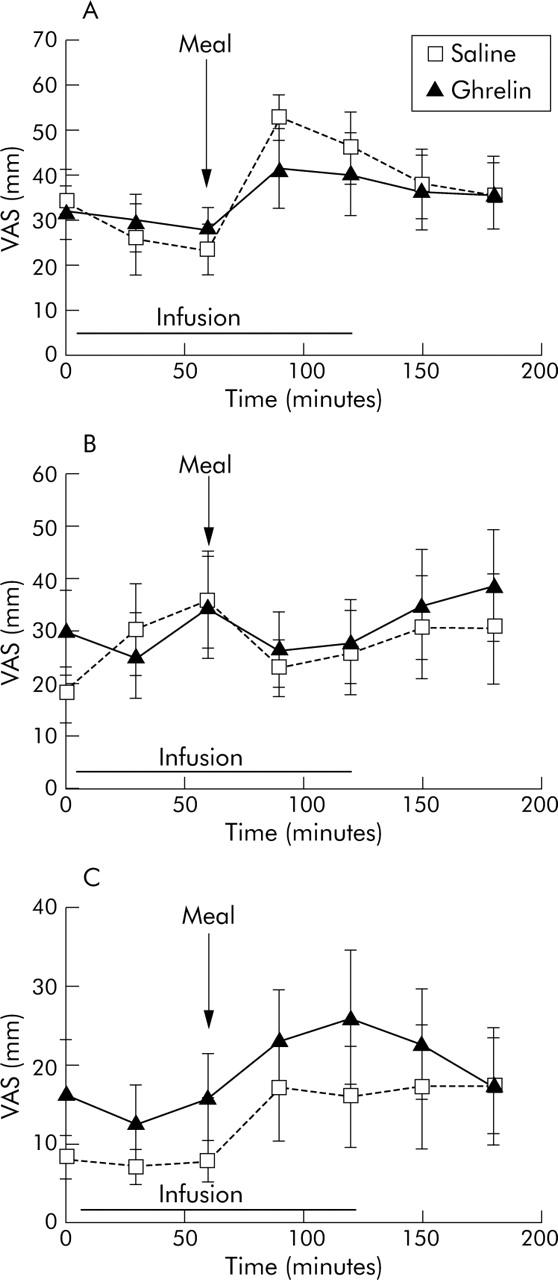

Symptoms

There were no significant differences between ghrelin and saline in any of the symptoms of bloating, hunger, or nausea during the infusions (p>0.05) (fig 4 ▶).

Figure 4.

There were no significant differences over time in symptoms of bloating (A), hunger (B), or nausea (C) between the two infusion days (p>0.05, ANOVA), as measured by visual analogue scales (VAS).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated for the first time that ghrelin improves gastric emptying in diabetic gastroparesis. To date, the only previous study to assess the effects of ghrelin on gastric emptying in humans employed the relatively insensitive method of the paracetamol absorption test.11 The potential of ghrelin as a prokinetic agent has been shown previously in vitro and in vivo studies. In vitro tissue bath studies have demonstrated that ghrelin increases neurally induced contractions secondary to electrical field stimulation in rodent fundus and antrum9,29 In both anaesthetised and conscious rats and mice, an increase in gastric emptying has been demonstrated after ghrelin administration.9,12 Ghrelin has also been shown to be able to reverse postoperative ileus in the rat and dog.30,31 In the former study, it did so even though motilin and its analogue erythromycin had no effect, suggesting a potent prokinetic action. This ability to reverse ileus has been supported recently in a rodent model of septic ileus where low doses of ghrelin were effective at reversing the ileus induced in rats by injection of lipopolysaccharide endotoxin.32

The mechanism by which ghrelin exerts enterokinetic effects is unclear. Ghrelin is an endogenous ligand for the growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHS-R). In the rat, GHS-R is expressed in the vagal afferent neurones of the nodose ganglion and migrates caudally.33 Immunohistochemistry studies have also demonstrated the presence of GHS-R in the myenteric plexus of the stomach and colon in both rats and humans15 and in guinea pig ileum.34 Centrally, GHS-R is also found in the hypothalamus and pituitary.35 Hence it is likely that ghrelin can act at both central and peripheral levels. The structural homology of ghrelin with motilin, and indeed the similarities between the human motilin receptor (GPR-38) and motility are via the motilin receptor. This was not supported by a recent study showing that ghrelin interacted only weakly with the rabbit motilin receptor.36

Recent studies have demonstrated that the vagus may be important in mediating the effects of ghrelin on gastrointestinal motility.13,37 Fujino et al have shown that the stimulatory effects of peripheral ghrelin on antral and duodenal motility in rats are greater in vagotomised rats than in intact rats.13 This suggests that vagotomy may upregulate ghrelin receptors in the myenteric plexus.

Ghrelin may be exacting its effect by altering autonomic tone to the gut. The increase in PP levels after either a sham or test meal is known be a marker of vagal integrity.7 However, this PP response may be blunted in diabetic patients with CAN.38 Nevertheless, delayed gastric emptying does not necessarily correlate with vagal neuropathy as a study has shown that although diabetics with CAN had a decreased PP response following a test meal, this was independent of gastric emptying.39 Our results are consistent with these findings. In the present study, PP secretory response, in terms of peak plasma PP level, correlated with the presence of CAN, but not with GER. We did not demonstrate any significant changes in preprandial or postprandial PP levels during ghrelin administration. It has previously been shown that an intravenous bolus of ghrelin in fasted healthy subjects increases plasma PP levels,40 but currently there are no comparative studies of the effects of continuous ghrelin infusion on PP levels in either healthy or diabetic subjects.

In agreement with previous studies, ghrelin increased GH secretion.11 Takeno et al have recently described a normal GH response to continuous intravenous ghrelin administration in vagotomised humans.41 In support of this, in the current study, all subjects showed a significant GH secretory response to intravenous ghrelin with no correlation between CAN and GH levels.

We did not observe the expected fall in plasma ghrelin levels in our diabetic patients following the test meal. The meal was 330 kcal and of mixed macronutrient composition, which would be expected to elicit a fall in levels in healthy controls. To control for the effects of hypo- and hyperglycaemia on gastric emptying, we employed a euglycaemic clamp throughout the studies. However, this did not control for circulating insulin levels which may have inhibitory effects on ghrelin release.42 In the current study, we measured total ghrelin, whereas differing effects of desacyl and acetylated ghrelin on gastric emptying in mice have recently been described.43 Finally, ghrelin dynamics in diabetic patients may also be affected by excretion and metabolism of the peptide. Some of our patients had renal impairment, which may lead to variable or delayed clearance of ghrelin as it has been shown that patients with renal failure have increased ghrelin levels.44 It is unlikely that our observation is due to the presence of vagal neuropathy as it has been demonstrated that vagotomy does not affect the nutrient induced suppression of ghrelin levels.45

Despite the evident increase in gastric emptying, ghrelin did not favourably improve symptoms in patients with diabetic gastroparesis. This phenomenon of enhanced gastric emptying not being accompanied by symptomatic improvement has been previously observed46 and remains unexplained. Symptoms of hunger, bloating, and nausea relate to a complex interplay of cortical and peripheral factors, and it seems that a simple effect at a gastric level is insufficient to alter symptom perception.

In conclusion, we have presented novel data that ghrelin increases gastric emptying in patients with diabetic gastroparesis. Although further studies are needed to investigate the mechanism by which this occurs, we propose that ghrelin and/or its analogues may represent a new class of prokinetic agents for the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Following confirmation of acute efficacy in improving gastric emptying from this study, longer term studies of these compounds are indicated.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Paul Bassett for his statistical advice.

Abbreviations

GH, growth hormone

GHS-R, growth hormone secretagogue receptor

PP, pancreatic polypeptide

CAN, cardiovagal autonomic neuropathy

GER, gastric emptying rate

BMI, body mass index

CASS, composite autonomic severity score

Published online first 5 August 2005

Conflict of interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Horowitz M, O’Donovan D, Jones KL, et al. Gastric emptying in diabetes: clinical significance and treatment. Diabet Med 2002;19:177–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horowitz M, Su YC, Rayner CK, et al. Gastroparesis: prevalence, clinical significance and treatment. Can J Gastroenterol 2001;15:805–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson D, Abell T, Rothstein R, et al. A double-blind multicenter comparison of domperidone and metoclopramide in the treatment of diabetic patients with symptoms of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:1230–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tack J, Janssens J, Vantrappen G, et al. Effect of erythromycin on gastric motility in controls and in diabetic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 1992;103:72–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frazee LA, Mauro LS. Erythromycin in the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Am J Ther 1994;1:287–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ewing DJ, Clarke BF. Autonomic neuropathy: its diagnosis and prognosis. Clin Endocrinol Metab 1986;15:855–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balaji NS, Crookes PF, Banki F, et al. A safe and noninvasive test for vagal integrity revisited. Arch Surg 2002;137:954–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, et al. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature 1999;402:656–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asakawa A, Inui A, Kaga T, et al. Ghrelin is an appetite-stimulatory signal from stomach with structural resemblance to motilin. Gastroenterology 2001;120:337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings DE, Purnell JQ, Frayo RS, et al. A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes 2001;50:1714–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wren AM, Seal LJ, Cohen MA, et al. Ghrelin enhances appetite and increases food intake in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:5992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dornonville d l C, Lindstrom E, Norlen P, et al. Ghrelin stimulates gastric emptying but is without effect on acid secretion and gastric endocrine cells. Regul Pept 2004;120:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujino K, Inui A, Asakawa A, et al. Ghrelin induces fasted motor activity of the gastrointestinal tract in conscious fed rats. J Physiol 2003;550:227–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edholm T, Levin F, Hellstrom PM, et al. Ghrelin stimulates motility in the small intestine of rats through intrinsic cholinergic neurons. Regul Pept 2004;121:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dass NB, Munonyara M, Bassil AK, et al. Growth hormone secretagogue receptors in rat and human gastrointestinal tract and the effects of ghrelin. Neuroscience 2003;120:443–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neary NM, Small CJ, Wren AM, et al. Ghrelin increases energy intake in cancer patients with impaired appetite: acute, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:2832–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagaya N, Kojima M, Uematsu M, et al. Hemodynamic and hormonal effects of human ghrelin in healthy volunteers. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2001;280:R1483–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talley NJ, Verlinden M, Geenen DJ, et al. Effects of a motilin receptor agonist (ABT-229) on upper gastrointestinal symptoms in type 1 diabetes mellitus: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut 2001;49:395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galil MA, Critchley M, Mackie CR. Isotope gastric emptying tests in clinical practice: expectation, outcome, and utility. Gut 1993;34:916–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jian R, Ducrot F, Ruskone A, et al. Symptomatic, radionuclide and therapeutic assessment of chronic idiopathic dyspepsia. A double-blind placebo-controlled evaluation of cisapride. Dig Dis Sci 1989;34:657–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones KL, Russo A, Stevens JE, et al. Predictors of delayed gastric emptying in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2001;24:1264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horowitz M, Maddox A, Harding PE, et al. Effect of cisapride on gastric and esophageal emptying in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology 1987;92:1899–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young MJ, Boulton AJ, Macleod AF, et al. A multicentre study of the prevalence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the United Kingdom hospital clinic population. Diabetologia 1993;36:150–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darwiche G, Almer LO, Bjorgell O, et al. Measurement of gastric emptying by standardized real-time ultrasonography in healthy subjects and diabetic patients. J Ultrasound Med 1999;18:673–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darwiche G, Bjorgell O, Thorsson O, et al. Correlation between simultaneous scintigraphic and ultrasonographic measurement of gastric emptying in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Ultrasound Med 2003;22:459–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Low PA, Benrud-Larson LM, Sletten DM, et al. Autonomic symptoms and diabetic neuropathy: a population-based study. Diabetes Care 2004;27:2942–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adrian TE, Bloom SR, Bryant MG, et al. Distribution and release of human pancreatic polypeptide. Gut 1976;17:940–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patterson M, Murphy KG, Le Roux CW, et al. Characterisation of ghrelin-like immunoreactivity in human plasma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:2205–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murray C, Dass N, Emmanuel A, et al. Facilitation by ghrelin and metoclopramide of nerve-mediated excitatory responses in mouse gastric fundus circular muscle. Br J Pharmacol 2002;136:18P. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trudel L, Tomasetto C, Rio MC, et al. Ghrelin/motilin-related peptide is a potent prokinetic to reverse gastric postoperative ileus in rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2002;282:G948–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trudel L, Bouin M, Tomasetto C, et al. Two new peptides to improve post-operative gastric ileus in dog. Peptides 2003;24:531–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Winter BY, De Man JG, Seerden TC, et al. Effect of ghrelin and growth hormone-releasing peptide 6 on septic ileus in mice. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2004;16:439–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Date Y, Murakami N, Toshinai K, et al. The role of the gastric afferent vagal nerve in ghrelin-induced feeding and growth hormone secretion in rats. Gastroenterology 2002;123:1120–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu L, Depoortere I, Tomasetto C, et al. Evidence for the presence of motilin, ghrelin, and the motilin and ghrelin receptor in neurons of the myenteric plexus. Regul Pept 2005;124:119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shuto Y, Shibasaki T, Wada K, et al. Generation of polyclonal antiserum against the growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHS-R): evidence that the GHS-R exists in the hypothalamus, pituitary and stomach of rats. Life Sci 2001;68:991–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Depoortere I, Thijs T, Thielemans L, et al. Interaction of the growth hormone-releasing peptides ghrelin and growth hormone-releasing peptide-6 with the motilin receptor in the rabbit gastric antrum. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003;305:660–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masuda Y, Tanaka T, Inomata N, et al. Ghrelin stimulates gastric acid secretion and motility in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000;276:905–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hossdorf T, Wagner M, Hoppe HW. Pancreatic polypeptide (PP) response to food in type I diabetics with and without diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Hepatogastroenterology 1988;35:238–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loba JM, Saryusz-Wolska M, Czupryniak L, et al. Pancreatic polypeptide secretion in diabetic patients with delayed gastric emptying and autonomic neuropathy. J Diabetes Complications 1997;11:328–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arosio M, Ronchi CL, Gebbia C, et al. Stimulatory effects of ghrelin on circulating somatostatin and pancreatic polypeptide levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:701–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takeno R, Okimura Y, Iguchi G, et al. Intravenous administration of ghrelin stimulates growth hormone secretion in vagotomized patients as well as normal subjects. Eur J Endocrinol 2004;151:447–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saad MF, Bernaba B, Hwu CM, et al. Insulin regulates plasma ghrelin concentration. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:3997–4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asakawa A, Inui A, Fujimiya M, et al. Stomach regulates energy balance via acylated ghrelin and desacyl ghrelin. Gut 2005;54:18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jarkovska Z, Rosicka M, Krsek M, et al. Plasma ghrelin levels in patients with end-stage renal disease. Physiol Res 2005;54:403–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams DL, Grill HJ, Cummings DE, et al. Vagotomy dissociates short- and long-term controls of circulating ghrelin. Endocrinology 2003;144:5182–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Talley NJ, Verlinden M, Geenen DJ, et al. Effects of a motilin receptor agonist (ABT-229) on upper gastrointestinal symptoms in type 1 diabetes mellitus: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut 2001;49:395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]