Abstract

Background and aims: The gastroprokinetic activities of ghrelin, the natural ligand of the growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHS-R), prompted us to compare the effect of ghrelin with that of synthetic peptide (growth hormone releasing peptide 6 (GHRP-6)) and non-peptide (capromorelin) GHS-R agonists both in vivo and in vitro.

Methods: In vivo, the dose dependent effects (1–150 nmol/kg) of ghrelin, GHRP-6, and capromorelin on gastric emptying were measured by the 14C octanoic breath test which was adapted for use in mice. The effect of atropine, NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (l-NAME), or D-Lys3-GHRP-6 (GHS-R antagonist) on the gastroprokinetic effect of capromorelin was also investigated. In vitro, the effect of the GHS-R agonists (1 µM) on electrical field stimulation (EFS) induced responses was studied in fundic strips in the absence and presence of L-NAME.

Results: Ghrelin, GHRP-6, and capromorelin accelerated gastric emptying in an equipotent manner, with bell-shaped dose-response relationships. In the presence of atropine or l-NAME, which delayed gastric emptying, capromorelin failed to accelerate gastric emptying. D-Lys3-GHRP-6 also delayed gastric emptying but did not effectively block the action of the GHS-R agonists, but this may be related to interactions with other receptors. EFS of fundic strips caused frequency dependent relaxations that were not modified by the GHS-R agonists. L-NAME turned EFS induced relaxations into cholinergic contractions that were enhanced by ghrelin, GHRP-6, and capromorelin.

Conclusion: The 14C octanoic breath test is a valuable technique to evaluate drug induced effects on gastric emptying in mice. Peptide and non-peptide GHS-R agonists accelerate gastric emptying of solids in an equipotent manner through activation of GHS receptors, possibly located on local cholinergic enteric nerves.

Keywords: ghrelin, gastric emptying, breath test, organ bath, electrical field stimulation

A class of synthetic molecules, termed growth hormone secretagogues (GHS), are known to stimulate growth hormone (GH) release through interaction with a specific receptor, the growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHS-R). GHS-R was cloned and identified in 19961 as a novel G protein coupled receptor, almost 20 years after the development of the first GHS.2 Cloning of this receptor allowed the discovery of the endogenous ligand of GHS-R, ghrelin, which was isolated from an unexpected source: the rat stomach.3 Two major forms of the 28 amino acid peptide ghrelin are found in the stomach and plasma: acylated ghrelin, which has an n-octanoylated serine in position 3; and des-acyl ghrelin, which accounts for 80% of circulating ghrelin.4 The n-octanoyl modification appears to be necessary for the growth hormone (GH) stimulatory effect of ghrelin.3

In addition to its effect on GH secretion, ghrelin is now considered to be an important regulator of energy homeostasis, stimulating food intake and decreasing fat utilisation during periods of negative energy balance.5,6 Moreover, ghrelin may be involved in the regulation of endocrine and exocrine pancreatic function, cardiac function, anxiety, and gastric functions (for a review see Murray and colleagues7). The various functional roles of ghrelin are supported by the evidence that GHS-R ligand binding sites and mRNA for GHS-R are widely expressed in the central nervous system and in several peripheral tissues.8,9

There is mounting evidence to support a physiological role for ghrelin in the regulation of gastrointestinal motility. In conscious rats and mice, ghrelin accelerates gastric emptying, enhances small bowel transit, and is able to overcome postoperative ileus.10–12 Exogenous administration of ghrelin also accelerates gastric emptying in humans.13 Recent observations have shown stimulation of interdigestive motility by ghrelin in rats and humans.14,15

However, the data obtained in small animals rely on a limited number of observations, mostly because of the lack of a convenient and reliable technique to measure gastric emptying. We decided to adapt the octanoic acid breath test, developed by our group in humans,16,17 for use in mice to evaluate the prokinetic potential of ghrelin. During the past 25 years, several peptide GHS (for example, growth hormone releasing peptide 6 (GHRP-6)) and non-peptide GHS (for example, MK-067718 and capromorelin19), have been developed that were orally active and had improved potency and bioavailability to stimulate release of GH. We therefore compared the effects of ghrelin with those of the GHS GHRP-6 (peptide) and capromorelin (non-peptide). Recent studies suggest that ghrelin may activate the enteric nervous system. Therefore, we also investigated the effect of these GHS-R agonists in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Rat ghrelin was obtained from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK). GHRP-6 and D-Lys3-GHRP-6 were purchased from Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland). Atropine sulphate and NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (l-NAME) were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, Missouri, USA). Capromorelin was a gift from B Coulie (Johnson and Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development, Beerse, Belgium). Des-octanoylated ghrelin was kindly provided by J Perret (Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium).

Animals

Healthy male NMRI mice (30–40 g body weight) were housed in cages at 20–22°C, with a 10−14 hour light-dark cycle. All procedures were approved by the ethics committee for animal experiments of the University of Leuven.

In vivo studies: breath test for gastric emptying

Animal preparation

Standard commercial mouse chow (4352 Muracon G; Nutreco Belgium NV, Gent, Belgium) (4.5% fat, 4% cellulose, 21% proteins, 1.404 kcal/g) was available ad libitum until the evening before the test. At 5pm food was removed and the test was started at 11am the following day. A wiremesh plate was inserted into the bottom of the cage to avoid coprophagia during the period of fasting. Tap water was freely available at all times, except during the test.

Test meal

The solid test meal consisted of 0.1 g of baked scrambled egg yolk, doped with 0.01 μCi 14C octanoic acid sodium salt (American Radiolabeled Chemicals Inc, St Louis, Missouri, USA), and mixed with 0.1 g of standard mice chow. Tap water was added and mixed to form a homogenous paste.

Before the start of the experiments, fasted mice (18 hours overnight) were trained twice weekly (three day intervals), for two weeks (four times), on a fixed time schedule, to eat spontaneously the test meal (without radioactive marker) within 60 seconds.

Breath test procedure: CO2 sampling

On the experimental day, fasted mice (n = 6) were injected intraperitoneally with the compound of interest and placed individually in an airtight tube adapted with an inlet valve through which continuous airflow (80% N2, 20% O2, 360 ml/min) passed, while the air outflow was bubbled through a vial containing the CO2 trapper tetramethylammonium hydroxide (1.3 mmol) (Acros, Geel, Belgium) to capture expired CO2. The tetramethylammonium hydroxide solution also contained the pH indicator thymolphtaleine (0.006%) to detect saturation by CO2. With the sampling time used in the present experiments (5 or 15 minutes), decolouration was never observed, indicating that all CO2 expired from a mouse was captured. The dimensions of the tube (diameter 50 mm, length 150 mm) allowed free movement of the mice.

After 23 minutes, a baseline breath sample (five minutes) was taken and after 30 minutes the tubes were opened, the 14C octanoic labelled test meal was given to the mouse, and the tube was closed again. Sampling was performed every five minutes during the first half hour and every 15 minutes during the next 4–6 hours. Scintillation liquid was added and the samples were counted in a β-counter. The amount of 14C octanoic acid present in the test meal (0.2 g) was also counted after oxidation.

Protocols

The time interval between the two breath tests was set at three or four days. Each group of mice first underwent a control breath test (saline injection), followed by three consecutive breath tests (compound of interest) and again a control breath test. The following compounds were injected intraperitoneally 30 minutes before mice received the test meal: bethanechol (20 mg/kg), ghrelin (1–150 nmol/kg), GHRP-6 (6–150 nmol/kg), or capromorelin (6–150 nmol/kg). The effect of the GHS-R agonists was compared with the mean of the control breath tests given before and after injection of the GHS-R agonists.

Modulation of the effect of the GHS-R agonists by pharmacological blockers was tested by intraperitoneal administration of atropine (1 mg/kg), L-NAME (50 mg/kg), or D-Lys3-GHRP-6 (5.6 µmol/kg) 15 minutes before the GHS-R agonists.

Data analysis

By plotting the excreted radioactive CO2 against time, a 14CO2 excretion curve was constructed. Using least squares analysis, the excretion curve was fitted to two mathematical equations16,17:

Equation 1: y = mkβe−kt(1−e−kt)β−1

Equation 2: y = atbe−ct

where y is the percentage of 14CO2 excretion in breath per hour, t is the time in hours; m, k, β, a, b, and c are regression estimated constants, with m the total amount of 14CO2 recovered when time is infinite.

From the curve of best fit, the gastric half excretion time (T1/2—that is, the time at which 50% of the total amount of 14CO2 was excreted) and the lag phase (Tlag—that is, the time between the meal and the start of the emptying process) were calculated using the following formulae:

Equation 1: T1/2 = (−1/k)*ln(1−2−1/β) and Tlag = ln(β)/k

Equation 2: T1/2 = 60 × (b/c) and Tlag = 60 × gammainv (0.5;1+b;1/c).

In vitro contractility measurements

Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and the stomach was removed and rinsed with ice cold saline. Circular muscle strips, freed from mucosa (length 10–15 mm, width 0.5 mm) were cut from the fundus and suspended vertically in an organ bath filled with Krebs solution (120.9 mM NaCl, 2.0 mM NaH2PO4, 15.5 mM NaHCO3, 5.9 mM KCl, 1.25 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, and 11.5 mM glucose) warmed at 37°C and gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2.

After one hour of equilibration at optimal stretch (0.75 g), reproducibility of the contractile response to acetylcholine (100 µM) was checked first and then electrical field stimulation (EFS) was applied via two parallel platinum rod electrodes using a Grass S88 stimulator. Frequency spectra (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 Hz) were obtained by pulse trains (duration 1 ms, train 10 s, 6 V). Voltage was kept constant using a Med Lab Stimu-Splitter II (Med Lab, Loveland, Colorado, USA). Each consecutive pulse train was followed by a 90 second interval. Mechanical responses in the smooth muscle strips were measured using an isometric force transducer/amplifier (Harvard Apparatus, Inc., South Natick, Massachusetts, USA) and stored on computer for analysis using the Windaq data acquisition system and a DI-2000 PGH card (Dataq Instruments, Akron, Ohio, USA).

To investigate the modification of neuroeffector transmission by the GHS-R agonists, the frequency spectrum was repeated in the presence of either ghrelin (1 µM), GHRP-6 (1 µM), or capromorelin (1 µM) (for 15 minutes) when a stable response was obtained at all frequencies. The response was also studied in the presence of L-NAME (300 µM), added to the tissue bath 15 minutes before application of the GHS-R agonists.

The mechanical response was calculated as the mean response during the stimulation period and was expressed in grams and normalised for the cross sectional area of the strip (g/mm2).

Statistics

All data are presented as mean (SEM). Intraindividual variations within mice were analysed by one way repeated measurements ANOVA analysis. The dose dependent effect of the GHS-R agonists on gastric emptying parameters was investigated by two way ANOVA analysis with one repeated measurement factor (saline v drug). In the case of significant dose factor effects, univariate tests of significance for planned comparisons were performed. The effect of pharmacological agents on gastric emptying induced by capromorelin was analysed by one way repeated measurements ANOVA analysis followed by univariate tests of significance for planned comparisons.

The effect of GHS-R agonists on EFS induced contractile responses was investigated by two way ANOVA analysis, with two repeated measures factors (agonist, frequency). In case of significant factor effects, preplanned tests with contrasts were performed to locate pairs of factor levels with significant differences in the examined variables.

All data were analysed with Statistica 6.0 (StatSoft, Inc, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA) and significance was accepted at a p value of <0.05.

RESULTS

In vivo study

Development of the 14C octanoic acid breath test in mice

Our group has pioneered the breath test for measurement of gastric emptying. For the purpose of this study, the test was adapted for use in mice. Instead of the sampling procedure used in humans, we captured all excreted CO2 by placing the mice in an airtight tube. Continuous airflow was passed through the tube, and bubbled through a vial containing CO2 trapper. Details are described in the methods section.

Excretion of 14CO2 by mice fed with a test meal labelled with 14C octanoic acid showed an initial rapid increase with a peak value after approximately 50 minutes, followed by a slower decrease and a return to baseline after about four hours (fig 1 ▶). The potential of this test to study the effect of ghrelin agonists on gastric emptying was evaluated by determining the effect of intraperitoneal injection, day to day variability, and effect of compounds known to affect emptying rate.

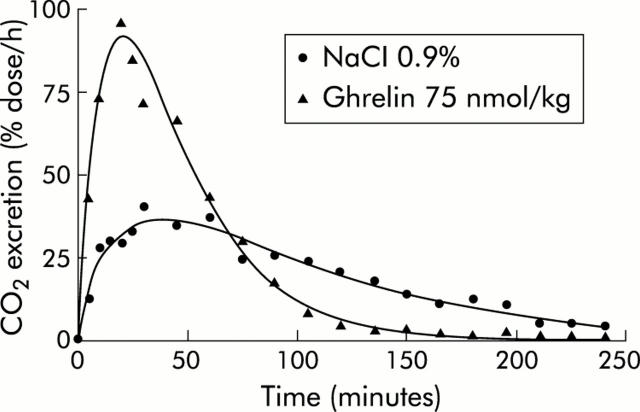

Figure 1.

Effect of ghrelin on gastric emptying in mice, as determined by the 14C octanoic breath test. Typical CO2 excretion curves obtained after ingestion of a solid meal enriched with 14C octanoic acid, 30 minutes after intraperitoneal injection of ghrelin (75 nmol/kg) or 0.9% NaCl in the same mouse.

Intraperitoneal injection could be experienced as a stressful event. Therefore, in the first series of experiments, a breath test was performed in 12 mice with and without intraperitoneal injection of saline (0.2 ml/mouse). Neither T1/2 (77.6 (6.5) v 83.6 (5.5) minutes; p = 0.54, n = 12) nor Tlag (35.4 (5.2) v 33.2 (2.3) minutes; p = 0.60, n = 12) differed significantly between saline injected and non-injected mice.

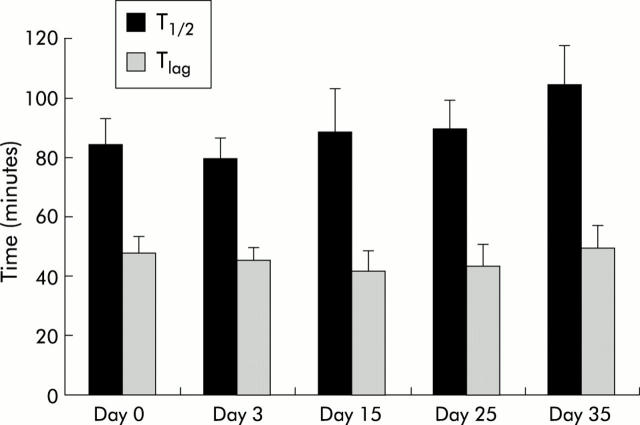

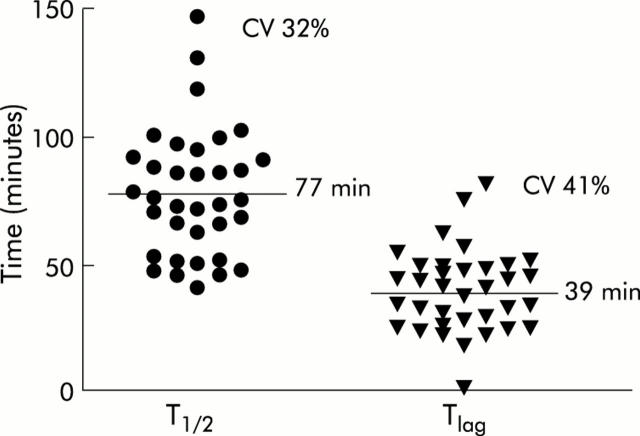

Secondly, in order to evaluate the variability of the test, gastric emptying parameters were compared in 12 mice injected with saline on five different days over a time period of 35 days. Analysis of variance did not reveal significant day to day variations within mice for T1/2 (p = 0.19) or Tlag (p = 0.82) (fig 2 ▶). Between mice, the coefficient of variation for T1/2 was 32.11% (n = 35) with a mean of 77.5 minutes (95% confidence interval (CI) 68.9–86.1 minutes). For Tlag the coefficient of variation was 40.8% with a mean of 39.2 minutes (95% CI 33.7–44.7 minutes) (fig 3 ▶).

Figure 2.

Intraindividual variations in gastric emptying parameters (T1/2 and Tlag) in mice. Mice were injected with 0.9% NaCl (0.2 ml intraperitoneally) on five different experimental days (days 0, 3, 15, 25, and 35), 30 minutes before the start of the 14C octanoic breath test, and the effect on T1/2 and Tlag was determined. Values are mean (SEM) of 12 mice. No significant differences were found.

Figure 3.

Interindividual variations in gastric emptying parameters (T1/2 and Tlag) in mice. T1/2 and Tlag were determined from the CO2 excretion curves in 36 mice after intraperitoneal injection of 0.9% NaCl 30 minutes before the start of the 14C octanoic breath test. Between mice the coefficient of variation (CV) was 32% for T1/2 and 41% for Tlag, with means of 77 minutes and 39 minutes, respectively.

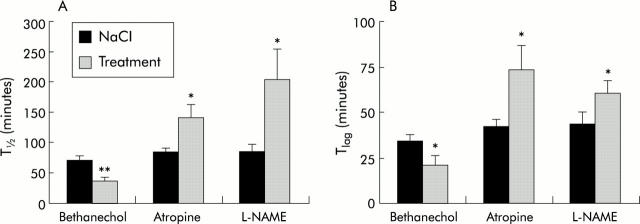

Thirdly, the effect of pharmacological agents known to enhance (bethanechol) or inhibit (atropine, L-NAME) gastric emptying in mice were tested. The muscarinic receptor agonist bethanechol (20 mg/kg intraperitoneally) significantly accelerated T1/2 (from 70.4 (6.3) to 37.5 (4.2) minutes; p<0.05) and Tlag (34.1 (3.8) to 20.9 (5.2) minutes; p<0.05). Diarrhoea occurred in all mice tested, as previously reported. 25 On the other hand, atropine (1 mg/kg intraperitoneally) and the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor L-NAME (50 mg/kg intraperitoneally) significantly lengthened T1/2 and Tlag. Data are summarised in fig 4 ▶.

Figure 4.

Effects of bethanechol, atropine, and NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (L-NAME) on gastric emptying parameters in mice. Mice underwent three consecutive breath tests consisting of subcutaneous injection of 0.9% NaCl followed by bethanechol (20 mg/kg), atropine (1 mg/kg), or L-NAME (50 mg/kg) and then 0.9% NaCl again. The effect on T1/2 (A) and Tlag (B) was calculated from the CO2 excretion curves of the control and drug treated mice. Results are mean (SEM) of 6–12 mice. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 versus saline treatment.

Effect of ghrelin, GHRP-6, and capromorelin on gastric emptying

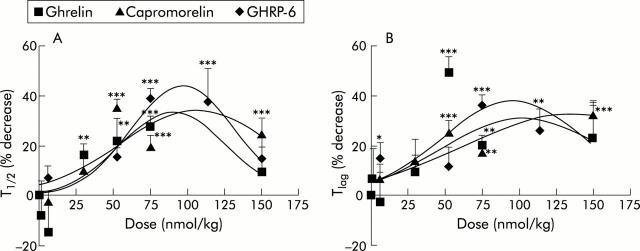

As illustrated in fig 1 ▶, intraperitoneally injection of ghrelin (75 nmol/kg) shifted the CO2 excretion curve to the left and upwards, reflecting a shortening of T1/2 (from 82.5 minutes to 36.1 minutes) and of Tlag (from 39 minutes to 20.4 minutes). The dose dependency of the effect of ghrelin was tested by administration of different doses of ghrelin, ranging from 1 to 150 nmol/kg. The minimal effective dose that accelerated gastric emptying was 30 nmol/kg. The dose-response curve was bell-shaped, reaching a maximum for T1/2 at 90.6 (16.3) nmol/kg and for Tlag at 96.6 (19.8) nmol/kg (fig 5 ▶). Des-octanoylated ghrelin, tested at 50 and 150 nmol/kg, did not affect gastric emptying (data not shown). GHRP-6 and capromorelin were equipotent with ghrelin, as the maximum effect on T1/2 was reached at comparable concentrations of 97.5 (3.5) nmol/kg for GHRP-6 and 106.5 (18.5) nmol/kg for capromorelin. Values for Tlag were also comparable (fig 5 ▶).

Figure 5.

Dose dependent effects of ghrelin, growth hormone releasing peptide 6 (GHRP-6), and capromorelin on gastric emptying in mice. Mice were injected with increasing doses of ghrelin (1–150 nmol/kg), GHRP-6 (6–150 nmol/kg), or capromorelin (6–150 nmol/kg) 30 minutes before ingestion of a meal enriched with 14C octanoic acid and the effects on gastric emptying parameters, T1/2 (A) and Tlag (B), were determined. Results are expressed as per cent decrease in time compared with injection of saline given before and after injection of the ghrelin agonists. Results are mean (SEM) of at least 12 mice. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 indicate significant decreases compared with saline treatment.

Pharmacology

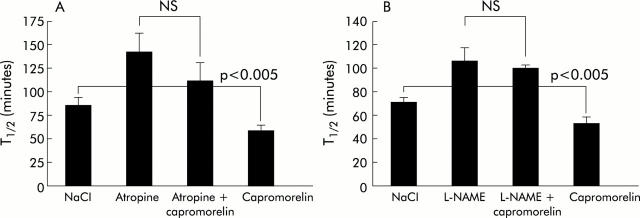

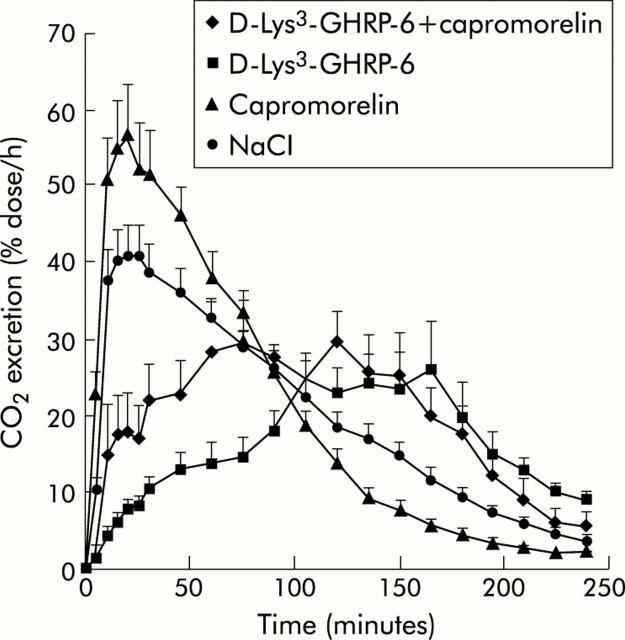

The effect of capromorelin on gastric emptying was characterised pharmacologically. In the presence of atropine (1 mg/kg), which lengthened T1/2 from 85.5 (8.1) minutes to 142.3 (20.6) minutes, capromorelin failed to accelerate gastric emptying (T1/2, 112.4 (18.3) minutes) significantly (p = 0.11) (fig 6 ▶). Similarly, capromorelin did not shorten Tlag significantly in atropine treated mice (data not shown). Capromorelin was also unable to reverse the inhibition of gastric emptying due to pretreatment with L-NAME (50 mg/kg) (fig 6 ▶). Pretreatment of mice with D-Lys3-GHRP-6, a putative GHS-R antagonist, significantly (p<0.01) delayed gastric half emptying from 82.7 (9.2) minutes to 201.6 (35.5) minutes and Tlag from 40.4 (4.4) to 121.2 (19.9) (p<0.01). Under these conditions, capromorelin (75 nmol/kg) shifted the CO2 excretion curve to the left and shortened T1/2 to 99.8 (18.0) minutes (p = 0.051 compared with D-Lys3-GHRP-6) and Tlag to 65.9 (15.2) minutes (p<0.01), indicating that the action of capromorelin was not blocked effectively by the GHS-R antagonist (fig 7 ▶). Similar changes in the CO2 excretion curves were also observed with ghrelin and GHRP-6 in D-Lys3-GHRP-6 treated mice (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Effects of atropine (A) and NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (L-NAME) (B) on the gastroprokinetic actions of capromorelin in mice. Mice were pretreated with atropine (1 mg/kg) or L-NAME (50 mg/kg) 15 minutes before administration of capromorelin (75 nmol/kg) and the effect was compared with that of treatment with capromorelin and atropine or L-NAME alone in the same mice. Results are mean (SEM) of at least 12 mice.

Figure 7.

Effects of D-Lys3-growth hormone releasing peptide 6 (GHRP-6) on gastric emptying and on the gastroprokinetic action of capromorelin in mice. The CO2 excretion curves were obtained after ingestion of a solid meal enriched with 14C octanoic acid, 30 minutes after intraperitoneal injection of NaCl or capromorelin. To evaluate the effect of D-Lys3-GHRP-6, mice were pretreated for 15 minutes with D-Lys3-GHRP-6 (5.6 µmol/kg) before administration of capromorelin or saline. All experiments were performed in the same mice. CO2 excretion curves are mean results of six mice.

In vitro study

Effect of GHS-R agonists on unstimulated preparations

Fundic strips of mice showed no spontaneous contractile activity but responded with a sustained contraction to 100 µM acetylcholine. Ghrelin (1 µM), GHRP-6 (1 µM), and capromorelin (1 µM) did not produce any responses (contraction or relaxation). However, higher concentrations of GHRP-6 (10 µM) caused a slowly developing transient contraction (9/13 strips), reaching a plateau within four minutes and recovering to the resting level after 7–8 minutes of application. This elevation in muscle tonus was 15.9 (3.9)% of the response to 100 µM acetylcholine.

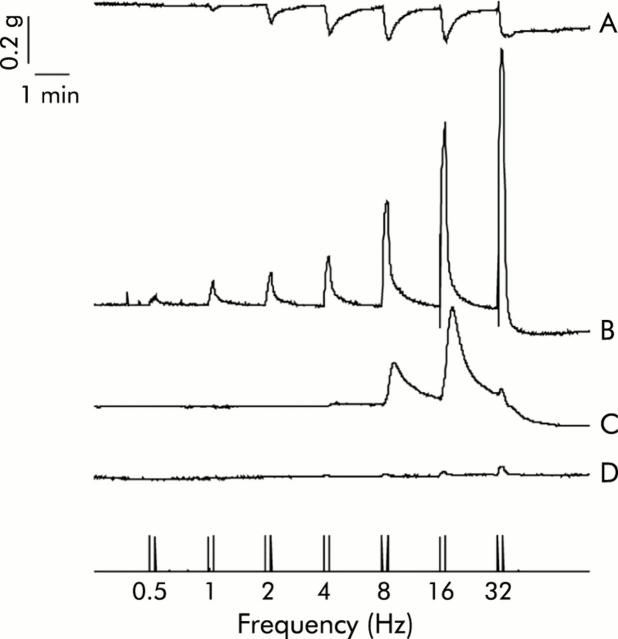

Effect of GHS-R agonists on neural responses in the fundus

EFS of mouse fundic strips caused frequency dependent weak relaxations between 2 Hz and 32 Hz during the stimulation period. An example is shown in fig 8 ▶. In the presence of L-NAME (300 µM), relaxations became strong contractions over the entire frequency range. These contractions were completely blocked by atropine (5 µM) at low frequencies (0.5–4 Hz) but at higher frequencies (8–32 Hz) small atropine resistant contractions remained. All responses were abolished in the presence of tetrodotoxin (1 µM). Representative tracings are shown in fig 8 ▶. Reversal of relaxation was also observed after treatment with the cholinesterase inhibitor physostigmine (100 nM).

Figure 8.

Representative tracings of mechanical responses of mice fundic strips elicited by electrical field stimulation (0.5–32 Hz) under different conditions: (A) control; (B) in the presence of NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (L-NAME 300 μM); (C) L-NAME plus atropine (5 μM); and (D) L-NAME plus atropine plus tetrodotoxin (1 μM).

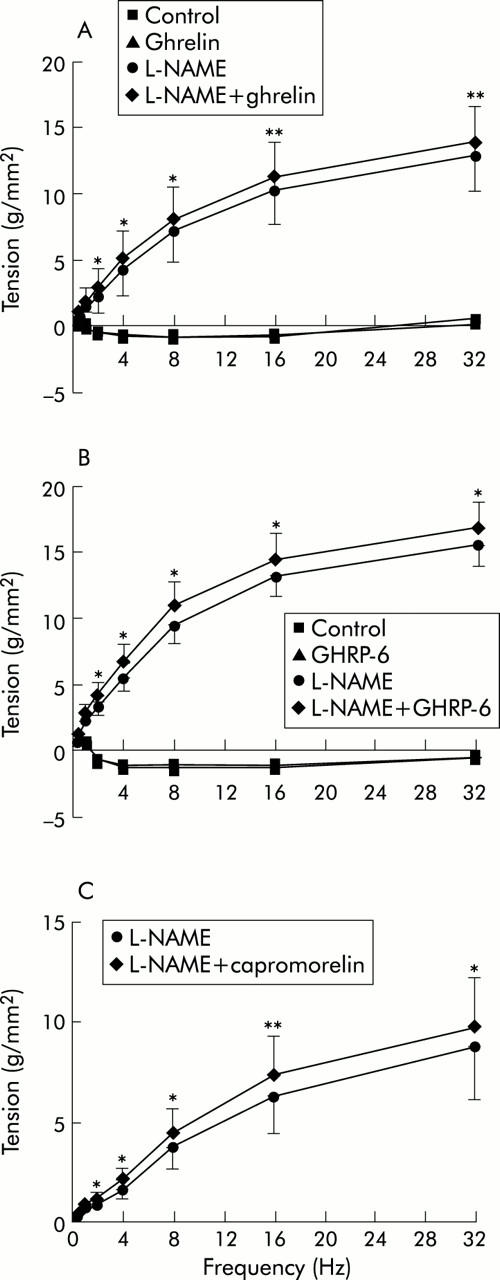

Under normal conditions, pretreatment with GHRP-6 (1 µM) or ghrelin (1 µM) did not affect EFS induced relaxations (fig 9 ▶). However, in the presence of L-NAME (300 µM), ghrelin (1–32 Hz), GHRP-6 (1–32 Hz), and capromorelin (2–32 Hz) significantly increased EFS induced contractions (fig 9 ▶). No significant difference was observed between the maximal changes in tension induced by the respective GHS-R agonists at the different frequencies (ghrelin 1.05 (0.24) g/mm2 at 8 Hz; GHRP-6 1.48 (0.44) g/mm2 at 16 Hz; capromorelin 1.10 (0.23) g/mm2 at 16 Hz).

Figure 9.

Effects of ghrelin (A), growth hormone releasing peptide 6 (GHRP-6) (B), and capromorelin (C) on electrical field stimulation induced mechanical responses of mice fundic strips. Muscle strips were electrically stimulated (0.5–32 Hz) preceding and during incubation with NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (L-NAME 300 µM) in the absence or presence of ghrelin (1 µM), GHRP-6 (1 µM), or capromorelin (1 µM), and the tension of the responses was measured. Results are mean (SEM) of five strip preparations from different mice. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 versus the frequency spectrum in the presence of L-NAME in the same strip preparation.

DISCUSSION

In the present study we have demonstrated that ghrelin and the synthetic GHS-R agonists GHRP-6 (peptide) and capromorelin (non-peptide) accelerate gastric emptying of solids. It is the first report demonstrating the gastroprokinetic action of synthetic peptide and non-peptide GHS-R agonists in mice. The effect may be mediated through potentiation of peripheral cholinergic pathways.

A variety of techniques have been used to assess gastric emptying in small laboratory animals. In most techniques, the animals are sacrificed and the content of the stomach and intestine is analysed by measuring its radioactivity, counting the remaining number of glass beads, or measuring the concentration of a marker, such as Evans blue or phenol red by spectrophotometry. Recently, non-invasive techniques such as the 13C octanoic breath test and whole body gamma scintigraphy have found wide application in humans, and they have also been adapted to small animals.20–22

We adapted the 14C octanoic breath test16 for use in mice. The use of 14C octanoic acid instead of 13C octanoic acid allows for a simpler and more sensitive detection technique. As implemented in mice, it almost eliminates sampling errors, as the total amount of CO2 is collected. The test allows serial measurements in the same mice, is non-invasive, and does not require handling or restraint of the animals in contrast with the scintigraphic test. Using the same mathematical analysis as that developed in humans, we showed that the gastric emptying parameters T1/2 and Tlag were not affected by injection of intraperitoneal saline, a stressful event for mice, and showed little day to day variability. Both parameters easily detected changes in gastric emptying caused by atropine, L-NAME, and bethanechol, which were previously reported to delay (atropine, L-NAME) or accelerate (bethanechol) gastric emptying in mice.23–25

Using the 14C octanoic breath test, we found that ghrelin stimulated gastric emptying in mice. The dose-response curve was bell-shaped and showed an optimal effect at 90 nmol/kg intraperitoneally. Earlier, less detailed, studies using more simple and less accurate methodologies reported acceleration at doses of 0.3 and 1.0 nmol/mice (about 10 and 33 nmol/kg)10 and 100 μg/kg (about 30 nmol/kg).12 No effects were observed with des-octanoyl ghrelin, indicating that just as for the effect of ghrelin on growth hormone secretion, the n-octanoyl modification on Ser3 is essential for the motility effects of ghrelin.26 The peptide and non-peptide GHS-R agonists, GHRP-6 and capromorelin, also accelerated gastric emptying at concentrations equipotent to ghrelin. In in vitro models it has been found that ghrelin, GHRP-6, and capromorelin have comparable affinities for GHS-R.27,28 Taken together, these data indicate that the observed effects are mediated via the GHS-R, although it will be noted in this respect that the results obtained with the antagonist were not unequivocal. Indeed, the GHS-R antagonist D-Lys3-GHRP-6 did not block the effect of the GHS-R agonists completely. However, it is possible that this antagonist is cross interacting with other receptors. A recent study showed that D-Lys3-GHRP-6 induces pronounced smooth muscle contractions in rat fundic strips by interacting with 5-HT1,2 receptors.29 Therefore, the effect of this antagonist by itself (delay in gastric emptying, which implies a physiological role for ghrelin in the regulation of gastric emptying) should also be interpreted with caution. Such a conclusion is not supported by the finding that gastric emptying in ghrelin knockout mice is normal.30 Assessment of the physiological role of ghrelin in the regulation of gastric emptying and of other functions will depend on the development of more potent and specific GHS-R antagonists.

For all compounds tested, dose-response relationships were bell-shaped. Orkin and colleagues31 also reported that the changes in intracellular Ca2+ in CHO cells, transfected with GHS-R1a cDNA following stimulation with hexarelin, were bell-shaped. There are many reasons for bell-shaped dose-response curves. Desensitisation is one of the possibilities, especially because the ghrelin receptor is susceptible to rapid desensitisation.31,32 Another possibility is the existence of high and low affinity receptor binding sites on different pathways.

Gastric emptying is a complex process, involving excitatory and inhibitory nerves, which may contribute to both acceleration and retardation of the emptying process. For example, L-NAME, which blocks inhibitory nitrergic nerves, delays gastric emptying, probably by interfering with gastric accommodation and pyloric relaxation. The effect of ghrelin may therefore involve both excitatory and inhibitory pathways, as suggested by the inability of ghrelin to overcome the delay induced by L-NAME and atropine.

Previous studies on the effect of ghrelin on gastric motility demonstrated the involvement of vagal and central ghrelin receptors. Thus the effect of ghrelin on gastric motor activity and gastric emptying was blocked by atropine and vagotomy in rats and mice.10,33 Fujino and colleagues14 showed that peripheral ghrelin may stimulate fasted small intestinal motor activity in rats by activating neuropeptide Y neurones in the brain through receptors on vagal afferents. In addition, expression of the ghrelin receptor in the rat nodose ganglion has been confirmed using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, direct sequencing, in situ hybridisation, histochemistry, and electrophysiology.34,35 Recent data indicate that ghrelin may also activate local pathways in the enteric nervous system. Ghrelin increases electrically evoked cholinergic neural responses in rat stomach strips36,37 and activates a subset of myenteric neurones in the guinea pig jejunum.38 There is also morphological evidence for the presence of ghrelin and ghrelin receptors in the myenteric plexus of the guinea pig ileum.39 Such local pathways may form a backup system activated under abnormal conditions or during pharmacological stimulation. For example, Fujino and colleagues14 showed that in rats, the motor effects in vivo are blocked by vagotomy, but that following vagotomy a local mechanism becomes operational. In the present study, we provided evidence that in mice, not only ghrelin but also GHRP-6 and capromorelin can increase electrically induced cholinergic contractions, masked by nitrergic nerves, without affecting smooth muscle tonus. Recently, ghrelin was shown to induce release of nitric oxide in the rat stomach40 and in our study a nitrergic pathway could be involved in acceleration of gastric emptying as the prokinetic effect in vivo was lost in the presence of L-NAME. However, our in vitro data do not provide evidence that nitric oxide mediated relaxation induced by EFS under normal conditions was modified by GHS-R agonists. A possible explanation is physiological antagonism by simultaneous ghrelin induced activation of cholinergic nerves and nitrergic nerves.

In conclusion, the 14C octanoic breath test is a non-invasive and valuable technique to measure gastric emptying in mice with the additional advantage that it allows repetitive measurements within the same mice. Ghrelin, GHRP-6, and capromorelin intraperitoneally accelerate gastric emptying in an equipotent manner, with bell-shaped dose-response relationships, by activating GHS receptors. GHS-R agonists also effectively potentiated EFS induced cholinergic responses in mouse fundic strips, suggesting that in addition to the known vagus nerve dependent mechanisms, ghrelin agonists can also activate peripheral receptors in the enteric nervous system. Ghrelin and ghrelin agonists have the potential to become useful therapeutic agents for the treatment of hypomotility disorders.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the Flemish Foundation for Scientific Research (contract FWO G.0144.04) and the Belgian Ministry of Science (contracts GOA 03/11 and IUAP P5/20).

Abbreviations

GH, growth hormone

GHS, growth hormone secretagogue

GHS-R, growth hormone secretagogue receptor

GHRP-6, growth hormone releasing peptide 6

l-NAME, NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride

EFS, electrical field stimulation

Published online first 20 April 2005

Conflict of interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Howard AD, Feighner SD, Cully DF, et al. A receptor in pituitary and hypothalamus that functions in growth hormone release. Science 1996;273:974–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowers CY, Chang J, Momany F, et al. Effects of enkephalins, enkephalins analogs on release of pituitary hormones in vitro In: MacIntyre I, Szelke H, eds. Molecular endocrinology. Amsterdam/North Holland: Elsevier, 1977:287–92.

- 3.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, et al. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature 1999;402:656–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hosoda H, Kojima M, Matsuo H, et al. Ghrelin and des-acyl ghrelin: two major forms of rat ghrelin peptide in gastrointestinal tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000;279:909–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tschop M, Smiley DL, Heiman ML. Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature 2000;407:908–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakazato M, Murakami N, Date Y, et al. A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature 2001;409:194–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray CD, Kamm MA, Bloom SR, et al. Ghrelin for the gastroenterologist: history and potential. Gastroenterology 2003;125:1492–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gnanapavan S, Kola B, Bustin SA, et al. The tissue distribution of the mRNA of ghrelin and subtypes of its receptor, GHS-R, in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:2988–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papotti M, Ghe C, Cassoni P, et al. Growth hormone secretagogue binding sites in peripheral human tissues. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:3803–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asakawa A, Inui A, Kaga T, et al. Ghrelin is an appetite-stimulatory signal from stomach with structural resemblance to motilin. Gastroenterology 2001;120:337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trudel L, Tomasetto C, Rio MC, et al. Ghrelin/motilin-related peptide is a potent prokinetic to reverse gastric postoperative ileus in rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2002;82:G948–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Winter BY, De Man JG, Seerden TC, et al. Effect of ghrelin and growth hormone-releasing peptide 6 on septic ileus in mice. Neurgastroenterol Motil 2004;16:439–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tack J, Depoortere I, Bisschops R, et al. Influence of ghrelin on gastric emptying and meal-related symptoms in gastroparesis growth hormone secretagogue. Gastroenterology 2004;126:485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujino K, Inui A, Asakawa A, et al. Ghrelin induces fasted motor activity of the gastrointestinal tract in conscious fed rats. J Physiol 2003;550:227–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tack J, Depoortere I, Bisschops R, et al. Ghrelin-induced gastric phase III activity in man is not accompanied by a plasma motilin peak. Gastroenterology 2004;126:74. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghoos YF, Maes BD, Geypens BJ, et al. Measurement of gastric emptying rate of solids by means of a carbon-labeled octanoic acid breath test. Gastroenterology 1993;104:1640–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maes B, Ghoos Y, Geypens B, et al. The combined 13C-glycine/14C-octanoic acid breath test: a double carbon labeled breath test to monitor gastric emptying rate of liquids and solids. J Nucl Med 1994;35:824–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patchett AA, Nargund RP, Tata JR, et al. Design and biological activities of L-163,191 (MK-0677): a potent, orally active growth hormone secretagogue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995;92:7001–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan LC, Carpino PA, Lefker BA, et al. Preclinical pharmacology of CP-424,391, an orally active pyrazolinone-piperidine growth hormone secretagogue. Endocrine 2001;14:121–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Symonds EL, Butler RN, Omari TI. Assessment of gastric emptying in the mouse using the [13C]-octanoic acid breath test. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2000;27:671–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schoonjans R, Van Vlem B, Van Heddeghem N, et al. The 13C-octanoic acid breath test: validation of a new noninvasive method of measuring gastric emptying in rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2002;14:287–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennink RJ, De Jonge WJ, Symonds EL, et al. Validation of gastric-emptying scintigraphy of solids and liquids in mice using dedicated animal pinhole scintigraphy. J Nucl Med 2003;44:1099–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeung CK, McCurrie JR, Wood D. A simple method to investigate the inhibitory effects of drugs on gastric emptying in the mouse in vivo. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 2001;45:235–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Winter BY, Bredenoord AJ, De Man JG, et al. Effect of inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase and guanylyl cyclase on endotoxin-induced delay in gastric emptying and intestinal transit in mice. Shock 2002;18:125–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osinski MA, Seifert TR, Cox BF, et al. An improved method of evaluation of drug-evoked changes in gastric emptying in mice. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 2002;47:115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumoto M, Hosoda H, Kitajima Y, et al. Structure-activity relationship of ghrelin: pharmacological study of ghrelin peptides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001;287:142–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carpino PA, Lefker BA, Toler SM, et al. Pyrazolinone-piperidine dipeptide growth hormone secretagogues (GHSs). Discovery of capromorelin. Bioorg Med Chem 2003;11:581–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Craenenbroeck M, Gregoire F, De Neef P, et al. Ala-scan of ghrelin (1–14): interaction with the recombinant human ghrelin receptor. Peptides 2004;25:959–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Depoortere I, Thijs TP, Peeters TL. The contractile effect of the ghrelin receptor antagonist D-Lys3-GHRP-6, in rat fundic strips is mediated through 5-HT receptors. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2003;15:580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Smet B, Depoortere I, Moreaux B, et al. Gastric emptying and food intake in ghrelin knockout mice. Gastroenterology 2004;126:90. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orkin RD, New DI, Norman D, et al. Rapid desensitisation of the GH secretagogue (ghrelin) receptor to hexarelin in vitro. J Endocrinol Invest 2003;26:743–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Camina JP, Carreira MC, El Messari S, et al. Desensitization and endocytosis mechanisms of ghrelin-activated growth hormone secretagogue receptor 1a. Endocrinology 2004;145:930–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masuda Y, Tanaka T, Inomata N, et al. Ghrelin stimulates gastric acid secretion and motility in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000;276:905–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Date Y, Murakami N, Toshinai K, et al. The role of the gastric afferent vagal nerve in ghrelin-induced feeding and growth hormone secretion in rats. Gastroenterology 2002;123:1120–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakata I, Yamazaki M, Inoue K, et al. Growth hormone secretagogue receptor expression in the cells of the stomach-projected afferent nerve in the rat nodose ganglion. Neurosci Lett 2003;342:183–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dass NB, Munonyara M, Bassil AK, et al. Growth hormone secretagogue receptors in rat and human gastrointestinal tract and the effects of ghrelin. Neuroscience 2003;120:443–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Depoortere I, De Winter B, Thijs T, et al. Comparison of the gastroprokinetic effects of ghrelin, GHRP-6 and motilin in rats in vivo and in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol 2005; (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Bisschops R, Vanden Berghe P, Depoortere I, et al. Ghrelin activates a subset of myenteric neurons in guinea pig jejunum. Gastroenterology 2003;124:1. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu L, Depoortere I, Tomasetto C, et al. Evidence for the presence of motilin, ghrelin and the motilin and ghrelin receptor in neurons of the myenteric plexus. Regul Pept 2005;124:119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka T, Ueyama H, Yoshie S, et al. Nitric oxide generation by ghrelin and localization of GHS-R in the rat stomach. Gastroenterology 2004;126:410. [Google Scholar]